Abstract

A finite-time adaptive neural network position tracking control method is considered for the fractional-order chaotic permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) via command filtered backstepping in this paper. Firstly, a neural network with a fractional-order parametric update law is utilized to cope with the nonlinear and unknown functions. Then the command filtered technique is introduced to address the repeated derivative problem in backstepping. In addition, a novel finite-time control method is proposed by employing the fractional-order terminal sliding manifolds, designing the error compensation mechanism and the new virtual control laws. The finite-time convergence of the tracking error can be guaranteed by the proposed controller. Finally, the designed control method is verified by simulation results.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fractional calculus is an evolving theory in many relevant sciences which is opening new areas in mathematics. It is a generalization of conventional differentiation and integration to arbitrary order [1]. Due to its potential applications and interesting properties, the fractional calculus has captured considerable attention from scholars in many fields [2–5]. Currently, many interesting results associated with the fractional calculus have been given [6–8]. The research shows that the fractional-order controllers are more advantageous than that of traditional integer-order ones. And also, some meaningful results have been reported on the stability problems in the scope of fractional calculus. For instance, by utilizing the fractional-order Lyapunov stability criterion, the robust consensus tracking problem is investigated in [9] for fractional-order multiagent systems with external disturbances and heterogeneous unknown nonlinearities. Based on the Chebyshev neural network (NN) technique, an adaptive synchronization approach is proposed in [10] for a class of fractional-order micro-electro-mechanical systems with chaotic oscillation. Therefore, the research of fractional-order system is a meaningful work.

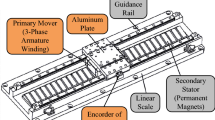

The permanent magnet synchronous motor (PMSM) has received wide acceptance for industry applications, owing to the superiorities of reliable operation, simple structure and high power density [11, 12]. The PMSM is a type of synchronous motor in which the field excitation generated in the stator windings is created by the rare-earth permanent magnet of the rotor. PMSM has been used in various areas such as robotics, wind generator, electric vehicles, pumps and ship electric propulsion systems. However, the multivariable and coupled mathematical model of PMSM can exhibit chaotic behavior while systemic parameters exceeding a certain critical value [13]. The chaotic motion for PMSM is not acceptable since it may lead to the controlled system collapse [14]. Recently, a large number of control design schemes for chaotic systems have been investigated. The OGY approach is considered to be an efficient tool for stabilizing chaotic systems [15]. The main weakness with this method is that it depends on an uncertain systemic parameter which is generally unmeasurable in real PMSM system. In order to avoid this problem, time-delay feedback control is a better choice for controlling unsteady periodic orbits of nonlinear systems with chaotic behavior [16]. One of the limitations with this approach is that the time-delay parameter is difficult to determine. Sliding mode control (SMC) is deemed to be a basic method for chaos control. In [17], an adaptive SMC approach combined composite feedback control technique is investigated to synchronize two different unknown dynamic nonlinear systems with disturbances and time-varying delay. However, the chattering phenomenon is the drawback of SMC in electrical power circuits. NN control scheme displays a great merit for controlling chaotic systems with uncertain parts. An NNs-based adaptive control strategy is presented in [18] to address the tracking control issue for input-delayed systems with state constraint. However, this method depends on precise mathematic model.

Adaptive backstepping technique has shown its advantages in controlling the nonlinear systems which does not satisfy matching conditions [19]. For the PMSM drive system with chaotic oscillation, the problem of position tracking control is addressed in [20] by using backstepping-based nonlinear adaptive control scheme. An adaptive SMC approach by fusing NN and backstepping is presented in [21] to control chaos of the PMSM. In [22], an adaptive fuzzy output feedback control method combined with the backstepping technique is considered for the PMSM with external load disturbance and parametric uncertainties. For a type of multi-input and multi-output (MIMO) uncertain nonlinear input-saturated systems, a fuzzy control method via backstepping technique is investigated in [23] to track a given trajectory. In [24], the tracking control issue for PMSM system with unknown parameters is studied by employing adaptive fuzzy finite-time control method. However, all the previously mentioned methods mainly focus on inter-order systems. Fractional differential equations can describe many natural behaviors briefly and accurately from the standpoint of modeling. Many researchers have devoted their efforts to the study of fractional-order PMSM systems [25–27]. In [25], the fractional-order model of PMSM is proposed by Yu et al. in the frequency domain, the experiment results have shown that the fractional differential equation presents more precise model for PMSM than conventional integer differential equation. Moreover, the stabilization problem for fractional-order PMSM is investigated by Guo and Mani et al. in [26, 27]. For fractional-order chaotic system, the synchronization issue is considered by using backstepping strategy in [28]. In [29], an adaptive fuzzy backstepping control method is investigated to converge the tracking error for a class of lower triangular structured fractional-order nonlinear uncertain systems. However, this work does not involve the finite-time convergence issue for nonlinear systems.

The finite-time control approach has several merits such as higher precision performance, faster response and better disturbance rejection property [30]. In [31], a finite-time hybrid adaptive intelligent backstepping SMC scheme is provided to suppress chaos for fractional-order chaotic systems. An adaptive NN terminal sliding mode output control approach for fractional-order nonlinear system with unknown actuator faults is proposed in [32] to obtain finite-time stability. One of the limitations with these methods is that the ‘explosion of complexity’ problem is unsolved in their works. Fortunately, dynamic surface control (DSC) technology affords an effective way to solve this issue. In [33], the NNs based adaptive DSC method is introduced to guarantee the convergence of the tracking error. However, this method ignores the effect of filtering errors induced by the DSC. Recently, command filtering-based backstepping technique combined an error compensation mechanism is an efficient method for solving the above problems [34]. For a class of high-order nonlinear systems, a finite-time tracking control problem is addressed in [35] by introducing the virtual control laws combined with finite-time filter. For the nonlinear saturated systems, a Levant differentiator combined fuzzy control approach is presented in [36] to ensure the finite-time convergence of the tracking error. However, the difference between this kind of the PMSM system and pure mathematical models is significant. Besides, the methods proposed in [33, 35, 36] are not applicable for fractional-order systems. To what degree new schemes can achieve finite-time convergence of the tracking error in the fractional-order PMSM system remains further study.

Motivated by the above discussions, a finite-time adaptive NN control approach is presented in this article. Compared with the existing achievements, the noteworthy contributions of this paper are summarized as:

- (1)

The issue of the repeated derivative in backstepping is handled by utilizing command filters. Meanwhile, the filtering errors are compensated in finite time by introducing a fractional-order error compensating system.

- (2)

A novel finite-time virtual signals are designed by employing appropriate terminal sliding surfaces such that the finite-time signal tracking is obtained.

- (3)

In the field of fractional calculus, we integrate adaptive NNs, command filtered backstepping, fractional-order error compensating mechanism and terminal sliding surface technique into finite-time controller, which can solve the tracking problem for fractional-order PMSM with chaotic motion in finite time.

2 Fractional-order PMSM and preliminaries

Consider the equation of PMSM as follows [20]:

where Θ, w, \(i_{q}\) and \(i_{d}\) denote system state variables, which mean the rotor position, the angular speed, the q-axis and d-axis currents. σ and γ stand for the dimensionless operating parameters. \(T_{L}\) is load torque, \(u_{q}\) and \(u_{d}\) represent the \(d-q\) axis voltages.

Let \(x_{1}=\varTheta \), \(x_{2}=w\), \(x_{3}=i_{q}\) and \(x_{4}=i_{d}\). The PMSM can be extended to the fractional domain as [26, 37]

where α stands for the fractional order.

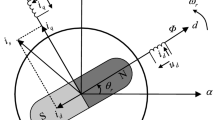

It should be mentioned that the dynamics of the system (2) are usually highly nonlinear on account of the coupling between the currents and the angular speed. Meanwhile, the parameter uncertainties may also influence the dynamic performance of the PMSM. Related research proves that the fractional-order PMSM exhibits chaos oscillation when σ and γ over a certain critical value in the case of zero external inputs. For instance, the fractional-order PMSM presents chaos with \(\sigma =5.46\) and \(\gamma =26.5\). Figure 1 shows the chaotic attractor with \(\alpha =0.98\). It is clear that the chaotic behavior can break the stable performance of the fractional-order PMSM system.

To remove the chaos in fractional-order PMSM, we use \(u_{q}\) and \(u_{d}\) as the control signals. The objective is to construct \(u_{q}\) and \(u_{d}\) such that the rotor position \(x_{1}\) follows the desired value \(x_{d}\) and the tracking error performs finite-time convergence. For convenience of the controller design, we introduce some properties of fractional-order differential and integral equations.

The Caputo definition of fractional-order derivative of the function \(f(t)\in C^{n}([0, \infty ], R)\) is given as [9]

where \(\alpha \in (m-1, m]\), \(m\in Z^{+}\), \(t\in [0, \infty )\), and \(\varGamma (\cdot )\) indicates the Gamma function.

The fractional-order integral is expressed by

Lemma 1

([7])

If\(x(t)\)is a derivable continuous function, then

Lemma 2

([38])

Let the origin\(x=0\)be an equilibrium point of a fractional-order non-autonomous system

where\(\alpha \in (0, 1)\)and\(f(t,x(t))\)is a Lipschitz continuous function. Suppose that there exists a Lyapunov function\(V(t,x(t))\)and class-Kfunctions\(g_{i}\) (\(i=1, 2, 3\)) satisfying

then\(x(t)\)can converge to the equilibrium point\(x=0\)of the system (6) as\(t\to +\infty \).

Lemma 3

([39])

Suppose that\(V(x)\)isC-regular, and\(x(t) : [0, +\infty )\to R^{n}\)is an absolutely continuous function on any compact interval of\([0, +\infty )\). Let\(\nu (t)=V(x(t))\)and\(\frac{1}{2}<\eta <1\). If the inequality

holds for\(t\ge 0\)and\(\alpha \in (0, 1)\), then

and

where

Remark 1

So far, a great number of control methods for dynamical systems with chaotic motion have been developed such as OGY technique, time-delay feedback control, fuzzy control and feedback linearization methods (see [15, 16, 22, 26] and the references therein). Nevertheless, the above control approaches have some limitations. The OGY approach needs a variable parameter for dynamical system which is generally unmeasurable. The employed method of time-delay feedback control suffers from the fact that it is hard to choose the time delay. The fuzzy control method presents the inference rules in an unsystematic form. For the feedback linearization approach, the accurate mathematical model is required. In [12, 18, 20, 32–34], the adaptive NN scheme shows a distinct advantage in dealing with nonlinear systems with uncertain function. Therefore, the adaptive NN technique is adopted to address the unknown nonlinear functions in this paper.

Lemma 4

([33])

Suppose that\(\varphi (x)\)is a continuous smooth function which is defined on a compact setΩ. Then there exists an ideal radial basis function (RBF) NN\(\phi ^{T}P(x)\)for a given\(\varepsilon >0\)such that

where\(\phi =[\phi _{1}, \phi _{2}, \ldots , \phi _{n}]^{T}\)is the weight vector with\(n>1\)and\(P(x)=[p_{1}(x), p_{2}(x), \ldots , p_{n}(x)]^{T}\)stands for the basis function vector and\(p_{i}(x)\)is Gaussian function with

where\(q_{i}\)represents the width of Gaussian function and\(\mu _{i}\)means the center vector.

3 Finite-time controller design

The finite-time adaptive NN control scheme via backstepping is shown in this section.

The tracking error variables are defined as

where \(x_{d}\) means the reference signal, \(a_{i,c}\) denotes the output of the finite-time command filter with virtual signal \(a_{i}\) as the input for \(i=1, 2\).

The compensated tracking errors are constructed as follows:

where \(\xi _{i}\) is the error compensating signal.

Remark 2

It should be noted that the errors caused by the command filters will degrade the control performance. Compared with adaptive NN output tracking control method designed in [32], our approach considers the repeated derivatives in backstepping. Meanwhile, we also employ an error compensation system to lessen the errors generated by the filters.

The error compensating signals are designed as

with \(k_{i}\) and \(g_{i}\) being positive constants for \(i=1, \ldots , 4\).

Remark 3

It should be mentioned that error compensating signals are finite-time stability by determining the properly parameters \(k_{i}\) and \(g_{i}\). A finite-time compensation approach for the filtering error is introduced in [24, 35, 36], however, this research focuses on the integer domain. We expand the compensation mechanism to fractional-order framework.

3.1 Terminal sliding manifolds

The sliding surfaces for system (2) can be chosen as

where \(i=1, \ldots , 4\), \(c_{i}>0\), \(d_{i}>0\), \(p_{i}\) and \(q_{i}\) are positive odd constants with \(q_{i}>p_{i}\), \(\chi _{i}\) is a continuous function.

From sliding mode method, one has \(s_{i}=0\) when the system operates in the sliding surface. Then, utilizing (17), we have

where \(l_{i}=-c_{i}^{p_{i}/q_{i}}\). Integrating both sides of (18), one has

Therefore, it can be concluded that the solution of the equation (18) is existent.

Theorem 1

Consider the dynamics system (18). Its states will go to zero in finite time.

Proof

Construct the Lyapunov functional candidate \(V_{\chi _{i}}\) as

From Lemma 1, the fractional-order derivative of \(V_{\chi _{i}}\) can be written as

According to Lemma 2, we see that the dynamics system (18) is asymptotically stable. In what follows, the finite-time convergence of states in the system (18) will be proved.

From inequality (21), we have

According to Lemma 3, we can see that the dynamics system (18) is stable. Moreover, the finite-time convergence of states is obtained. This completes the proof. □

3.2 Control law design

Step 1: Select the Lyapunov functional candidate as

Taking the derivative \(V_{1}\), one has

Substituting the derivative of \(\xi _{1}\) into (24) yields

Then the virtual control signal \(a_{1}\) is constructed as

where \(b_{1}>0\), \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{1}\) represents the estimation of \(\varepsilon _{1}\) and \(\varepsilon _{1}=0\).

The following command filter is used to obtain \(a_{1,c}\):

where \(a_{1,c}=\zeta _{1}\) denotes the output of filter.

Thus, substituting (26) into (25) yields

Step 2: Select the Lyapunov function \(V_{2}\) as

Taking its derivative, one has

Substituting (28) into (30), we can show the following form:

where \(f_{2}(Z_{2})=\sigma ({x_{3}}-{x_{2}})-T_{L}-{{}^{C}_{0}D_{t}^{\alpha }}a_{1,c}-x_{3}\) and \(Z_{2}=[x_{1}, x_{2}, x_{3}, x_{4}, x_{d}]^{T}\).

Remark 4

It should be mentioned that the external load torque \(T_{L}\) and the parameter σ are unknown. We cannot achieve the control signal directly. To avoid this problem, the RBF NN is introduced to adaptively approximate the unknown part \(f_{2}\).

From Lemma 4, for a given \(\varepsilon _{2}>0\), the existence of a RBF NN is ensured and it satisfies \(f_{2}=\phi _{2}^{T}P_{2}(Z_{2})+\delta _{2}(Z_{2})\), where \(\delta _{2}(Z_{2})\) stands for the approximation error with \(\vert \delta _{2}(Z_{2}) \vert \le \varepsilon _{2}\).

The virtual control signal \(a_{2}\) is designed as

where \(b_{2}>0\), \(\hat{\phi }_{2}\) means the estimation of \(\phi _{2}\), \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{2}\) denotes the estimation of \(\varepsilon _{2}\).

Similarly, one can obtain the output \(a_{2,c}\) of the filter with \(a_{2}\) being its input. Thus, from (16), (30) and (32), the derivative of \(V_{2}\) is given in the following form:

where \(\tilde{\phi }_{2}=\phi _{2}-\hat{\phi }_{2}\).

Step 3: Construct the Lyapunov function candidate \(V_{3}\) as

By differentiating \(V_{3}\), it follows that

Substituting (33) into (35), we get

where \(f_{3}(Z_{3})=-{x_{3}}-{x_{2}}{x_{4}}+\gamma {x_{2}}-{{}^{C}_{0}D_{t}^{ \alpha }}a_{2,c}\) and \(Z_{3}=Z_{2}\).

Remark 5

It is clear that the function \(f_{3}\) involves the nonlinear term \(-x_{2}x_{4}\) and the differential part \(-{{}^{C}_{0}D_{t}^{\alpha }}a_{2,c}\), these will increase the complexity of the control law \(u_{q}\). In order to avoid this problem, the RBF NN is adopted to estimate the nonlinear function \(f_{3}\).

Similarly, for a given \(\varepsilon _{3}\), there exists a RBF NN satisfying \(f_{3}=\phi _{3}^{T}P_{3}(Z_{3})+\delta _{3}(Z_{3})\), where \(\vert \delta _{3}(Z_{3}) \vert \le \varepsilon _{3}\).

Furthermore, the control signal \(u_{q}\) can be given by

where \(b_{3}>0\), \(\hat{\phi }_{3}\) means the estimation of \(\phi _{3}\), \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{3}\) denotes the estimation of \(\varepsilon _{3}\).

By taking (16), (36) and (37) into account, it can be verified that

where \(\tilde{\phi _{3}}=\phi _{3}-\hat{\phi }_{3}\).

Step 4: Consider the Lyapunov function candidate \(V_{4}\) as

Differentiating \(V_{4}\) yields

Then substituting (38) into (40) results in

where \(f_{4}(Z_{4})=-x_{4}+x_{2}x_{3}\) and \(Z_{4}=Z_{3}\).

Similarly, there exists a RBF NN \(\phi _{4}^{T}P_{4}(Z_{4})\) for a given \(\varepsilon _{4}>0\) such that \(f_{4}=\phi _{4}^{T}P_{4}(Z_{4})+\delta _{4}(Z_{4})\), where \(\vert \delta _{4}(Z_{4}) \vert \le \varepsilon _{4}\).

Then the control law \(u_{d}\) can be constructed as

where \(b_{4}>0\), \(\hat{\phi }_{4}\) means the estimation of \(\phi _{4}\), \(\hat{\varepsilon }_{4}\) denotes the estimation of \(\varepsilon _{4}\).

By taking (16), (41) and (42) into account, it follows that

where \(\tilde{\phi _{4}}=\phi _{4}-\hat{\phi }_{4}\).

4 Stability analysis

In this section, the stability of the designed controller is analyzed.

Theorem 2

For the fractional-order PMSM with chaotic motion, load torque disturbance and parameters uncertainties, the controllers with virtual signals\(a_{1}\) (26), \(a_{2}\) (32), control signals\(u_{q}\) (37), \(u_{d}\) (42), compensating signals (16), command filter (27) and adaptive laws (48) can ensure the tracking errors converge to zero in finite time.

Proof

Construct the Lyapunov function in the following form:

where \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}=\varepsilon _{i}-\hat{\varepsilon }_{i}\), \(m_{i}\) and \(r_{i}\) are positive constants.

The derivative of V can be written as

By utilizing the inequality \(|\delta _{i}|\le \varepsilon _{i}\), one has

Thus, substituting (46) into (45), it can be verified that

According to (47), the adaptive laws are constructed in the following form:

From (47) and (48), it can be derived that

Then we define

Obviously, we have the following inequality:

Thus, there exists a κ-function ρ such that

Then, referring to Lemma 2, we see that the compensated tracking errors go to zero asymptotically.

Now it is time to prove that the sliding motion happens in finite time. Construct the Lyapunov function candidate as

The inequality (49) can be rewritten as

Furthermore, there exists a positive constant n such that [3]

Substituting (57) into (56), it can be derived that

According to Lemma 3, we can conclude that the sliding motion occurs in finite time. Since \(v_{i}=z_{i}-\xi _{i}\), then if we can show that \(\xi _{i}\) goes to zero in finite time, this also means that the tracking errors \(z_{i}\) will go to zero within finite time.

In what follows, select the Lyapunov function candidate \(V_{\xi }\) to prove that \(\xi _{i}\) (\(i=1, \ldots , 4\)) go to zero within finite time:

Then the time derivative of \(V_{\xi }\) can be written as

According to [40], we know that the command filters can guarantee \(|a_{i,c}-a_{i}|\le \psi _{i}\) in finite time. Then we have

where \(g_{0}=\min (g_{i})\), \(\bar{\psi }=\max (\psi _{i})\). Then, if we select appropriate parameter \(g_{0}\) such that \(\sqrt{2}g_{0}-2\sqrt{2}\bar{\psi }>0\), then \(\xi _{i}\) will go to zero in finite time. The proof is completed. □

Remark 6

Compared with the backstepping based adaptive control strategy considered in [2, 12, 20, 22–24, 28, 29, 33, 34], the following superiorities are obtained. First, the designed error compensating mechanism in [22, 23, 34] can only achieve asymptotic stability. In this paper, we employ the sign functions as in (16) such that the finite-time convergent of the error compensation system can be guaranteed. Second, the conventional control laws constructed in [2, 12, 20, 22, 29] can only guarantee the tracking errors are bounded. However, the controllers (26), (32), (37) and (42) provided in this paper can guarantee that the tracking errors are finite-time stable, which can ensure the fractional-order PMSM system with fast convergence performance. Third, the finite-time tracking control method proposed in [24] for PMSMs does not cover the generalized fractional-order system. However, our method can solve the finite-time control issue for fractional-order PMSM. Fourth, the adaptive NN technique via backstepping developed in [12, 33, 34] does not take into account the approximation errors. In this paper, the adaptive law \({{}^{C}_{0}D_{t}^{\alpha }}{\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i}=r_{i}\vert s_{i} \vert \) in (48) is constructed to compensate the approximation errors, which can ensure the closed-loop system with high quality tracking performance.

5 Simulation results

5.1 Performance analysis

Simulation results are given to show the effectiveness of the constructed finite-time adaptive NN control for the fractional-order PMSM in this section. Let the reference signal be \(x_{d}=\sin (t)\). The simulation is conducted under the condition of \(x_{1}(0)=0.2\), \(x_{2}(0)=x_{3}(0)=0\), \(x_{4}(0)=10\) and the external disturbance

The control parameters of the designed controllers are selected as \(k_{1}=25\), \(k_{2}=20\), \(k_{3}=25\), \(k_{4}=50\), \(c_{1}=0.01\), \(c_{2}=0.02\), \(c_{3}=0.01\), \(c_{4}=0.01\), \(d_{1}=60\), \(d_{2}=50\), \(d_{3}=55\), \(d_{4}=60\), \(b_{1}=5\), \(b_{2}=10\), \(b_{3}=10\), \(b_{4}=10\), \(m_{2}=m_{3}=m_{4}=1500\), \(r_{1}=0.1\), \(r_{2}=0.2\), \(r_{3}=0.1\), \(r_{4}=0.5\).

Furthermore, the RBF NNs are adopted as the following way. The RBF NNs \(\phi _{2}^{T}P_{2}(Z_{2})\), \(\phi _{3}^{T}P_{3}(Z_{3})\), \(\phi _{4}^{T}P_{4}(Z_{4})\) cover nine nodes with centers \(\mu _{i}\) spaced evenly in the range \([-8, 8]\) and the widths are set to be 2, respectively.

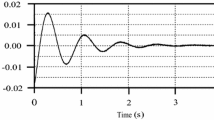

Previous study shows that the fractional-order PMSM occurs chaos without controllers. The trajectory tracking of the fractional-order PMSM is shown in Figs. 2–5 with the designed controllers being applied. The time curves of the output response \(x_{1}\) and the desired signal \(x_{d}\) are depicted in Fig. 2(a). As we can see, the state \(x_{1}\) can track the desired value \(x_{d}\) precisely. A change of load torque disturbance does not result in performance degradation. The amplitude of the tracking error between \(x_{1}\) and \(x_{d}\) reduces to zero in finite time. Figure 2(b) displays the curve of tracking error, it shows that the rotor position tracking error goes to zero rapidly. The time curves of \(s_{i}\), \(i=1,2,3\) are provided in Figs. 3–4. From both Figs. 3 and 4, one sees that the sliding motion obtains in a short time. Therefore, a conclusion can be achieved that our method has good convergence properties.

The curves of \(d-q\) axis currents are given in Fig. 5. The results of trajectory tracking performance for different α are shown in Fig. 6. Figure 6(a) is the curve of the position, and the tracking error is given in Fig. 6(b). The time evolution of \(s_{1}\) is displayed in Fig. 6(c). It can be obviously observed that the fractional-order PMSM system achieves finite-time stability despite the orders are different, which means that the proposed controllers are effective for fractional-order PMSM system.

Figure 7 exhibits the performance of the controller when perturbation of the parameter γ occurs. As the system parameter γ alters a little, the system is still stable. That is to say, the designed controllers show good robustness for the system with parameter perturbations and uncertainties in the whole process.

Although there exist chaotic motion, load torque disturbance, parameter perturbations and uncertainties, the proposed method is an efficient approach to obtaining the finite-time stability for fractional-order chaotic PMSM system.

5.2 Scheme contrast

To display the superiority of the finite-time controller presented in this paper, the result is given comparing with [34] under the condition of \(\alpha =0.98\). For the fractional-order PMSM system, the neural networks command filtered backstepping controller (NCBC) proposed in [34] can be constructed as

The command filter has the following form:

where \(\varphi _{1}\) indicates the output of the filter with q being the input.

The adaptive law is designed as

where \(k_{if}>0\) for \(i=1, \ldots , 4\), h and \(l_{i}\) for \(i=2,3,4\) are positive constants, \(P_{if}\) denote the NNs basis function.

Compared with the NCBC proposed in [34], our method can realize finite-time signal tracking. Figure 8 depicts the trajectory tracking contrast between NCBC and the proposed control strategy. It reveals that our scheme is more accurate than the NCBC. Therefore, it is concluded that the fractional-order chaotic PMSM possesses better performance by utilizing the proposed control strategy.

Remark 7

The NCBC method proposed in [34] cannot guarantee the tracking error coverages to zero in finite time. Through these comparisons, we can know that our method can solve the tracking problem for fractional-order PMSM in finite time.

Remark 8

So far, to the best of our knowledge, no results are available for finite-time control of fractional-order PMSM. Compared with the existing literature, the finite-time tracking control issue is considered in this paper for fractional-order chaotic PMSM.

6 Conclusions

In this brief, a finite-time adaptive NN control method is presented to deal with the position tracking issue of fractional-order PMSM with chaotic motion, load torque disturbance, parameter perturbations and uncertainties. The finite-time adaptive control approach consists of adaptive NNs, command filters, backstepping, fractional-order error compensating mechanism and terminal sliding surface technique. With the aid of adaptive NNs, the unknown function can be estimated by designed weight adaptive laws. The command filters with a compensating mechanism not only solve the ‘explosion of complexity’ problem in backstepping, but also reduce the filtering errors. Meanwhile, the fractional-order terminal sliding manifolds are integrated into control signals to ensure finite-time stability of the tracking error. Our simulation results show the superior performance of the proposed control strategy for the fractional-order chaotic PMSM. In future work, we will study the finite-time tracking control problem for incommensurate fractional-order PMSM system with unmeasured states and input saturation.

References

Selvaraj, P., Kwon, O., Sakthivel, R.: Disturbance and uncertainty rejection performance for fractional-order complex dynamical networks. Neural Netw. 112, 73–84 (2019)

Luo, S., Li, S., Tajaddodianfar, F., Hu, J.: Observer-based adaptive stabilization of the fractional-order chaotic mems resonator. Nonlinear Dyn. 92(3), 1079–1089 (2018)

Aghababa, M.P.: Stabilization of a class of fractional-order chaotic systems using a non-smooth control methodology. Nonlinear Dyn. 89(2), 1357–1370 (2017)

Xu, S., Sun, G., Ma, Z., Li, X.: Fractional-order fuzzy sliding mode control for the deployment of tethered satellite system under input saturation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 55(2), 747–756 (2019)

Li, G., Sun, C.: Adaptive neural network backstepping control of fractional-order Chua–Hartley chaotic system. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019(1), 148 (2019)

Gu, Y., Wang, H., Yu, Y.: Stability and synchronization for Riemann–Liouville fractional-order time-delayed inertial neural networks. Neurocomputing 340, 270–280 (2019)

Aguila-Camacho, N., Duarte-Mermoud, M.A., Gallegos, J.A.: Lyapunov functions for fractional order systems. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 19(9), 2951–2957 (2014)

Hua, C., Chen, J., Guan, X.: Fractional-order sliding mode control of uncertain quavs with time-varying state constraints. Nonlinear Dyn. 95(2), 1347–1360 (2019)

Gong, P., Lan, W.: Adaptive robust tracking control for multiple unknown fractional-order nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 49(4), 1365–1376 (2019)

Luo, S., Li, S., Tajaddodianfar, F., Hu, J.: Adaptive synchronization of the fractional-order chaotic arch micro-electro-mechanical system via Chebyshev neural network. IEEE Sens. J. 18(9), 3524–3532 (2018)

Bak, Y., Lee, K.-B.: Constant speed control of a permanent-magnet synchronous motor using a reverse matrix converter under variable generator input conditions. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 6(1), 315–326 (2018)

Lu, S., Wang, X., Li, Y.: Adaptive neural network control for fractional-order pmsm with time delay based on command filtered backstepping. AIP Adv. 9(5), 055105 (2019)

Chen, X., Hu, J., Peng, Z., Yuan, C.: Bifurcation and chaos analysis of torsional vibration in a pmsm-based driven system considering electromechanically coupled effect. Nonlinear Dyn. 88(1), 277–292 (2017)

Ju, J., Li, W., Wang, Y., Fan, M., Yang, X.: Dynamics and nonlinear feedback control for torsional vibration bifurcation in main transmission system of scraper conveyor direct-driven by high-power pmsm. Nonlinear Dyn. 93(2), 307–321 (2018)

Gritli, H., Belghith, S.: Bifurcations and chaos in the semi-passive bipedal dynamic walking model under a modified ogy-based control approach. Nonlinear Dyn. 83(4), 1955–1973 (2016)

Pyragas, V., Pyragas, K.: State-dependent act-and-wait time-delayed feedback control algorithm. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 73, 338–350 (2019)

Mobayen, S.: Chaos synchronization of uncertain chaotic systems using composite nonlinear feedback based integral sliding mode control. ISA Trans. 77, 100–111 (2018)

Li, D.-P., Liu, Y.-J., Tong, S., Chen, C.P., Li, D.-J.: Neural networks-based adaptive control for nonlinear state constrained systems with input delay. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 99, 1–10 (2019)

Lu, S., Wang, X.: Observer-based command filtered adaptive neural network tracking control for fractional-order chaotic pmsm. IEEE Access 7, 88777–88788 (2019)

Yu, J., Chen, B., Yu, H., Lin, C., Ji, Z., Cheng, X.: Position tracking control for chaotic permanent magnet synchronous motors via indirect adaptive neural approximation. Neurocomputing 156, 245–251 (2015)

Luo, S., Gao, R.: Chaos control of the permanent magnet synchronous motor with time-varying delay by using adaptive sliding mode control based on dsc. J. Franklin Inst. 355(10), 4147–4163 (2018)

Niu, H., Yu, J., Yu, H., Lin, C., Zhao, L.: Adaptive fuzzy output feedback and command filtering error compensation control for permanent magnet synchronous motors in electric vehicle drive systems. J. Franklin Inst. 354(15), 6610–6629 (2017)

Yu, J., Shi, P., Dong, W., Lin, C.: Command filtering-based fuzzy control for nonlinear systems with saturation input. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 47(9), 2472–2479 (2017)

Yang, X., Yu, J., Wang, Q.-G., Zhao, L., Yu, H., Lin, C.: Adaptive fuzzy finite-time command filtered tracking control for permanent magnet synchronous motors. Neurocomputing 337, 110–119 (2019)

Yu, W., Luo, Y., Chen, Y., Pi, Y.: Frequency domain modelling and control of fractional-order system for permanent magnet synchronous motor velocity servo system. IET Control Theory Appl. 10(2), 136–143 (2016)

Guo, Y., Ma, B.: Asymptotic stabilization of fractional permanent magnet synchronous motor. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 13(2), 021003 (2018)

Mani, P., Rajan, R., Shanmugam, L., Joo, Y.-H.: Adaptive fractional fuzzy integral sliding mode control for pmsm model. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 27(8), 1674–1686 (2019)

Shukla, M.K., Sharma, B.: Backstepping based stabilization and synchronization of a class of fractional order chaotic systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 102, 274–284 (2017)

Liu, H., Pan, Y., Li, S., Chen, Y.: Adaptive fuzzy backstepping control of fractional-order nonlinear systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 47(8), 2209–2217 (2017)

Selvaraj, P., Sakthivel, R., Kwon, O.: Finite-time synchronization of stochastic coupled neural networks subject to Markovian switching and input saturation. Neural Netw. 105, 154–165 (2018)

Bigdeli, N., Ziazi, H.A.: Finite-time fractional-order adaptive intelligent backstepping sliding mode control of uncertain fractional-order chaotic systems. J. Franklin Inst. 354(1), 160–183 (2017)

Hashtarkhani, B., Khosrowjerdi, M.J.: Neural adaptive fault tolerant control of nonlinear fractional order systems via terminal sliding mode approach. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 14(3), 031009 (2019)

Yu, J., Shi, P., Dong, W., Chen, B., Lin, C.: Neural network-based adaptive dynamic surface control for permanent magnet synchronous motors. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 26(3), 640–645 (2015)

Yu, J., Chen, B., Yu, H., Lin, C., Zhao, L.: Neural networks-based command filtering control of nonlinear systems with uncertain disturbance. Inf. Sci. 426, 50–60 (2018)

Yu, J., Shi, P., Zhao, L.: Finite-time command filtered backstepping control for a class of nonlinear systems. Automatica 92, 173–180 (2018)

Yu, J., Zhao, L., Yu, H., Lin, C., Dong, W.: Fuzzy finite-time command filtered control of nonlinear systems with input saturation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 48(8), 2378–2387 (2018)

Xue, W., Li, Y., Cang, S., Jia, H., Wang, Z.: Chaotic behavior and circuit implementation of a fractional-order permanent magnet synchronous motor model. J. Franklin Inst. 352(7), 2887–2898 (2015)

Li, Y., Chen, Y., Podlubny, I.: Mittag-Leffler stability of fractional order nonlinear dynamic systems. Automatica 45(8), 1965–1969 (2009)

Peng, X., Wu, H., Song, K., Shi, J.: Global synchronization in finite time for fractional-order neural networks with discontinuous activations and time delays. Neural Netw. 94, 46–54 (2017)

Levant, A.: Higher-order sliding modes, differentiation and output-feedback control. Int. J. Control 76(9–10), 924–941 (2003)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and reviewers for their reading.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors’ information

Senkui Lu and Longda Wang are currently pursuing the Ph.D. degree at Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China. Xingcheng Wang is a Professor and Doctoral advisor at Dalian Maritime University.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number 60574018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL designed, analyzed and wrote the paper. XW guided the full text. LW analyzed the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, S., Wang, X. & Wang, L. Finite-time adaptive neural network control for fractional-order chaotic PMSM via command filtered backstepping. Adv Differ Equ 2020, 121 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02572-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02572-6