Abstract

Background

Rehabilitation research does not always improve patient outcomes because of difficulties implementing complex health interventions. Identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation fidelity is critical. Not reporting implementation issues wastes research resources and risks erroneously attributing effectiveness when interventions are not implemented as planned, particularly progressing from single to multicentre trials. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity (CFIF) facilitate identification of barriers and facilitators. This review sought to identify barriers and facilitators (determinants) affecting implementation in trials of complex rehabilitation interventions for adults with long-term neurological conditions (LTNC) and describe implementation issues.

Methods

Implementation, complex health interventions and LTNC search terms were developed. Studies of all designs were eligible. Searches involved 11 databases, trial registries and citations. After screening titles and abstracts, two reviewers independently shortlisted studies. A third resolved discrepancies. One reviewer extracted data in two stages; 1) descriptive study data, 2) units of text describing determinants. Data were synthesised by (1) mapping determinants to CFIF and CFIR and (2) thematic analysis.

Results

Forty-three studies, from 7434 records, reported implementation determinants; 41 reported both barriers and facilitators. Most implied determinants but five used implementation theory to inform recording. More barriers than facilitators were mapped onto CFIF and CFIR constructs. “Patient needs and resources”, “readiness for implementation”, “knowledge and beliefs about the intervention”, “facilitation strategies”, “participant responsiveness” were the most frequently mapped constructs. Constructs relating to the quality of intervention delivery, organisational/contextual aspects and trial-related issues were rarely tapped. Thematic analysis revealed the most frequently reported determinants related to adherence, intervention perceptions and attrition.

Conclusions

This review has described the barriers and facilitators identified in studies implementing complex interventions for people with LTNCs. Early adoption of implementation frameworks by trialists can simplify identification and reporting of factors affecting delivery of new complex rehabilitation interventions. It is vital to learn from previous experiences to prevent unnecessary repetitions of implementation failure at both trial and service provision levels. Reported facilitators can provide strategies for overcoming implementation issues. Reporting gaps may be due to the lack of standardised reporting methods, researcher ignorance and historical reporting requirements.

Systemic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42015020423

Similar content being viewed by others

Contributions to the literature

-

Research shows developing new rehabilitation for people with long-term neurological conditions is complicated because interventions are complex and are delivered in complex places like hospitals and in the community. Understanding these complexities is important to learn how to overcome them.

-

We found a wide range of issues (positive and negative) described in over 40 rehabilitation studies. These start to help us understand the early problems researchers face and how they overcame some of them, which is important planning for future services.

-

These findings bring together useful descriptions and contribute to the gaps in the rehabilitation research literature.

Background

Moving rehabilitation from the research environment into everyday clinical practice requires it to be delivered as intended, in different contexts, achieving the required patient outcomes [1, 2]. Rehabilitation in the United Kingdom (UK) works within complex health and social care systems and involves the delivery of complex interventions [3, 4] to people with long-term neurological conditions (LTNC). LTNCs include conditions such as stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI). There are between 4.7 and 12.5 million people in the UK living with a neurological condition that negatively impacts their lives [5,6,7]. Rehabilitation is important because it aims to enable people to reach and maintain optimal physical, sensory, intellectual, psychological and social functioning [8] and is recommended for people with LTNC in the UK [9]. Rehabilitation is measured as part of the National Health Service (NHS) outcomes framework [10] because of its beneficial outcomes for patients and healthcare systems [11].

Rehabilitation interventions cannot change population health outcomes unless adopted [12]. Rehabilitation research is complicated because interventions are complex and this increases the unpredictability of results [13]. Findings do not always translate into improved patient outcomes because of difficulties implementing the intervention in clinical practice [14, 15]. However, there is also a dearth of descriptions of the difficulties faced implementing interventions during trials [16]. This may help to explain why successful single-centre studies do not always progress and scientific discovery halted with interventions that have been determined ineffective when in fact the problem may have been related to its implementation [17]. To improve outcomes for people with LTNC and achieve return on investment in research, there is a need to understand factors that affect the implementation of complex interventions [18, 19]. Examining barriers and facilitators associated with delivering interventions in trials is required to learn more about real-world contexts, which may also have a further benefit of reducing waste in research [16, 20].

As an example, vocational rehabilitation (VR) is a form of rehabilitation that supports people with LTNC, to remain in or return to work. Unfortunately, evidence for the effectiveness of VR in people with LTNC is lacking, particularly for TBI [21, 22]. Few studies describe VR for TBI in detail [23] or report its implementation in the context of trials. The exception to this is a UK feasibility RCT where an embedded process evaluation described barriers and facilitators to implementing early VR to people with TBI across three English National Health Service (NHS) sites [24]. The lack of effectiveness and implementation evidence may account, in part, for patchy commissioning of VR services in the UK [25, 26]. Policy makers and commissioners require details about how an intervention will work in different contexts with different populations whilst maintaining optimum outcomes [27, 28]. Trialists can provide assurance about intervention effectiveness by demonstrating that it has been implemented as planned, thus preventing erroneous attribution of effectiveness when interventions are not implemented as planned (type III errors ) [29].

Barriers (hindering delivery) and facilitators (enabling delivery) are often identified together as “determinants” [30]. Factors affecting implementation have been described in over 60 theoretical frameworks [31]. The Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity (CFIF) [32] brings together previous scholarly work understanding how closely interventions are implemented as planned, known as implementation fidelity. In CFIF, fidelity is conceptualised under two domains: adherence and potential moderating factors. Adherence refers to whether an intervention has reached the right recipients (coverage), that recipients then received, and the provider gave the correct intervention content in the right frequency and duration (dose). Moderating factors include the recipient’s response to the intervention, the comprehensiveness of policy description (intervention complexity), facilitation strategies and quality of delivery.

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [33] is considered a meta-theory, bringing together 19 existing theories in a bid to represent every aspect that may be encountered when implementing an intervention. Therefore, CFIR incorporates a wide range of theories in 39 constructs, arranged across five domains (intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, individuals involved and the process of implementation). CFIF and CFIR are used together [34, 35] to explore and describe in detail the complex factors affecting the extent to which an intervention is delivered as intended (fidelity) and those that affect its delivery (implementation).

The literature on the implementation of rehabilitation for adults with LTNCs has not been brought together or described and is not therefore well understood. One exception is a systematic review that focussed on a specific intervention of home-based stroke rehabilitation and investigated determinants (barriers and facilitators) of success [36]. It identified seven studies that provided some information on barriers and facilitators. Siemonsma (2014) found that while none of the studies set out to explicitly identify implementation issues, the use of an implementation framework [37] helped to identify determinants that could then inform suitable implementation strategies in future research.

Differences exist between the implementation of complex interventions within a trial compared with clinical practice but little is known about the unique context of the trial setting [16, 38]. For example, changing clinicians’ behaviours on unproven interventions is challenging [39], whereas this may be more straightforward with evidence-based interventions. Clinicians often have to deliver interventions in addition to and alongside their usual role without necessarily being experienced in doing this within the research environment [16, 28, 39], whereas those in everyday clinical practice may not have the additional trial-related paperwork or study protocol restrictions. Barriers and facilitators to implementing complex interventions are reported infrequently [39] and even less so in the trial context [16]. Therefore, understanding of what to expect, how to make the most of facilitators and how to overcome barriers is limited. This situation will perpetuate the significant problem of wasting already stretched research funds, that often come from public money, by trialists repeating known but unreported failures in intervention implementation [16, 20]. Understanding implementation issues, will help trialists design and improve strategies to ensure interventions are implemented with fidelity so that the effectiveness of these interventions can be measured with confidence [39, 40].

The aim of this study was to identify the barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of complex rehabilitation interventions with adults with LTNC within the research context.

Methods

This review is reported in accordance with PRISMA guidelines [41] and the checklist is available in the supplementary materials. A protocol was developed by the review team (JH, KR, PL) and registered on PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews [42] (CRD42015020423).

Studies of any design were included if they reported barriers and or facilitators, implementing a rehabilitation intervention, with adults, with LTNCs in developed countries. The WHO’s definition of “rehabilitation” was used: “Rehabilitation is a set of interventions needed when a person is experiencing or is likely to experience limitations in everyday functioning due to ageing or a health condition, including chronic diseases or disorders, injuries or traumas. Examples of limitations in functioning are difficulties in thinking, seeing, hearing, communicating, moving around, having relationships or keeping a job.” [43] Rehabilitation is considered a complex intervention and a complex intervention is characterised by the number and difficulty (e.g. skill requirements) of behaviours required by those delivering the intervention, the number of groups or organisational levels targeted by the intervention, the number and variability of outcomes, the degree of flexibility or tailoring of the intervention permitted [3]. Interventions that were solely related to medication, medical or surgical procedures, or assistive technologies, e.g. rehabilitation equipment or e-health, or solely focussed on environmental adaptations, were excluded. No studies were excluded on the basis of research methodology to broaden the scope. Peer-reviewed studies published in English, from database inception until December 2018 were considered, including conference abstracts, and grey literature. Opinion pieces and non-systematic literature reviews were excluded, but they were citation searched. Studies were included from “Developed regions” according to the United Nations’ M49 Standard grouping [44].

Literature searches were developed across a range of databases using medical subject headings and EMTREE thesaurus related to implementation of complex interventions. The search algorithm included the following three main concepts, “barriers and facilitators to implementation”, “long-term neurological conditions” and “complex interventions”. The MEDLINE search algorithm is available in the supplementary materials. The search strategy was adjusted as appropriate for each medical, health, social care and psychology databases from inception to December 2018:

MEDLINE (Ovid: 1946 to current); EMBASE (Ovid: 1980 to current); PsycINFO (Ovid: 1806 to current); CINAHL with Full Text (EBSCOHost: 1981 to current); ASSIA (ProQuest: 1987 to current); AMED (Ovid: 1985 to current); Cochrane Library (Wiley: 1996 to current); Joanna Briggs Institute (Ovid: 1998 to current).

PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews was searched for ongoing reviews in the same topic area. Research in progress was identified through the UK Clinical Trials Gateway (ukctg.nihr.ac.uk) and the US National Library of Medicine register (clinicaltrials.gov). Citation searches of included studies were undertaken using SCOPUS, Web of Science and Google Scholar. Hand searches of references of relevant papers were conducted. Opportunistic identification of papers were included in the search and marked as not being gathered from other systematised strategies. Searches were recorded in Excel and saved by date on each database where possible. All citations from the database searches were exported to EndNote X8 with duplicates removed and additional results added.

Titles and abstracts were screened by JH against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full texts were obtained for all titles that met the inclusion criteria or where there was uncertainty. After screening titles and abstracts, two reviewers independently shortlisted studies. A third resolved discrepancies. No additional study information was required from authors. Reasons for excluding studies were documented.

Whilst there are a range of critical appraisal tools for both quantitative and qualitative research appraising the quality of how the primary studies were conducted was not of chief concern for this review. The adjectives describing barriers and facilitators reported in each study were of key importance rather than the primary studies’ effectiveness outcomes. It was expected that a wide range of adjectives would be used that would aid interpretation of reported barriers and facilitators to implementing a complex rehabilitation intervention within a research context, which were not appropriate to assess for quality.

A data extraction table was developed into a Microsoft Excel sheet by the review team. Data was extracted in two stages: (1) descriptive study data and (2) line by line review of units of text (word, sentence, paragraph) describing barriers and facilitators. Extracted data were tabulated onto the Excel sheet to compare data.

A descriptive synthesis was conducted to understand the determinants of implementing interventions in the review in two stages and the review team discussed interpretations to minimise bias. Firstly, units of text were coded by JH on a line by line basis whilst maintaining the correct context of the study. The coding was based on the construct definitions of both frameworks before being individually mapped to constructs of the adapted version of CFIF [45] and CFIR. CFIF was used to identify implementation fidelity and CFIR to identify broader implementation [46]. JH undertook coding and mapping and reported back to the review team to discuss findings and check codes. Differences of opinion about codes and where they were mapped to were discussed before confirming the final map.

Where included studies described data related to study participants, carers, staff delivering the intervention and others, e.g. acceptability, beliefs about the intervention, this was mapped to the relevant constructs on CFIF and CFIR. Where studies did not report data clearly, this was inferred by considering the context of the whole paper and then mapped to relevant constructs. Because studies reported data from different groups using differing methods, it was not feasible to compare them in a meaningful way by for instance counting frequencies.

Secondly, thematic analysis of the units of text was used to reveal more detail about the reported barriers and facilitators and to understand how these were reported. JH conducted the thematic analysis and reported back to the review team to discuss findings and check themes. Differences of opinion about themes were discussed before confirming a final list.

Reviewers were not blinded to publication sources, authors or the countries in which the studies were conducted. However, publisher bias was addressed by maintaining a list of publication sources for all studies to ensure that the search was not limited. Author bias was treated in the same way. Bias towards particular developed countries was addressed by ensuring that the search strategy included a wide range of terms.

Results

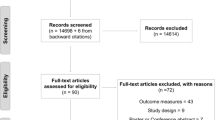

The database search returned 7434 records, of which 7331 were excluded. No studies were identified from the grey literature search. Forty-six additional records were identified through author citation search and through recommendations from experts. Full texts were obtained where available for the remaining 149 records and 106 were excluded (see Fig. 1 for reasons). Forty-three studies (including one systematic review) were included in the review.

Details of studies are described in supplementary materials and included: one systematic review (with seven studies that were excluded from the review as primary research); 13 randomised controlled trials (RCTs); eight non-randomised studies (pre- and post-test and mixed methods designs); seven process evaluations (embedded in RCTs); eight qualitative studies (two embedded in a RCT); and five case reports.

The 43 studies were published across 22 different journals between 2006 and 2018. Research was conducted in eight countries:

-

Twelve studies from Netherlands [36, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]

-

One from Norway [83]

-

One international [16]

-

One UK study [35]

More than 4000 patients with a range of LTNCs were in receipt of interventions: stroke featured in 22 studies, dementia in seven, Parkinson’s disease in four, multiple sclerosis and mixed LTNCs in three, Huntingdon’s disease in two, motor neurone disease and spinal cord injury in a single study each. The complex interventions delivered were:

-

Exercise-based interventions in twelve [16, 50, 51, 58, 67, 68, 70, 71, 73, 76,77,78]

-

Home-based rehabilitation in eight studies [35, 36, 49, 52, 53, 56, 60, 82]

-

Psychosocial and educational interventions in seven [48, 54, 57, 64, 74, 75, 83]

-

Vocational rehabilitation [24], music therapy [55], oral care [84], memory aids [66], bathing [69], self-management [80] in a single study each

More than 400 healthcare professionals delivered the interventions and included, in order of prevalence: occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, psychologists, music therapists, recreational therapists, nurses, physicians, rehabilitation assistants and social workers. Not all studies reported how many professionals, or which profession was involved. Therefore, the numbers are approximate.

Most studies (n = 41) reported both barriers and facilitators, while two reported only barriers. Whilst most studies (n = 40) described data collection methods, only 10 explicitly examined barriers and facilitators informed by these implementation theories:

-

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services [85]

-

Treatment Implementation model [86]

-

Framework for the Introduction and Evaluation of Innovations [37]

-

Normalisation Process Theory [87]

-

Combinations of Interventions [88]

-

Theoretical Domains framework [89]

-

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research [33]

-

Conceptual Framework for Implementation Fidelity [32]

Data synthesis

Stage one—barriers and facilitators mapped to frameworks

Figure 2 is a visual representation of reported barriers and facilitators mapped to the constructs of CFIF and CFIR. All studies reported barriers and/or facilitators to implementing the complex intervention under investigation, as this was part of inclusion criteria. Studies reported barriers or facilitators across the implementation frameworks’ constructs and some were co-mapped as both barriers and facilitators.

Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of barriers, facilitators and co-mapped barriers and facilitators in each of the 35 constructs across the two frameworks (Tables 1 and 2). Definitions for the 35 constructs can be seen in the CFIR website resource cfirguide.org.

The five constructs with the most determinants mapped to them were “patient needs and resources” (n = 42), “facilitation strategies” (n = 31), “readiness for implementation” (n = 32), “participant responsiveness” (n = 28) and “knowledge and beliefs of the intervention” (n = 27). Examples of determinants relating to these constructs are described in Table 3.

The construct “implementation climate” was mapped mostly to barriers (n = 16). Examples of these included a failure within the organisation to pre-plan for loss of staff permanently [47], on vacation, other leave, e.g. maternity [47, 59], wards or units under high pressure and unable to dedicate staff time to the intervention delivery and existing ward/department tasks seen as a priority [60, 65, 67, 84], a lack of pre-planning for the impact of clinicians’ needs to travel longer-than-usual distances to visit patients [75, 82], interruption of intervention delivery due to cancelled appointments, being discharged early and hospital admissions [76,77,78,79], influential clinician not on-board and advising patients not to engage with the intervention [50], some departments considered the intervention at odds with strategic goals [56], negative attitudes of staff in organisations [16, 24, 38].

Only facilitators were mapped to the construct “reflecting and evaluating” (n = 5), which related to time afforded therapists in coaching to gain confidence in intervention delivery and having an allocated person to provide feedback to aid learning [52, 65]. “Facilitation strategies” attracted the most facilitators (n = 25) (examples reported in Table 4).

Some constructs had no determinants mapped:

-

“Quality of delivery” (CFIF’s moderating factors) relates to the manner in which a teacher, volunteer, or staff member delivers a programme.

-

“Design quality and packaging” relates to the perceived excellence in how the intervention is bundled, presented, and assembled. (CFIR; intervention characteristics).

-

“Peer pressure” (CFIR; outer setting) relates to competitive pressure to deliver an intervention.

-

“Planning”, “engaging”, “executing” (CFIR; process) relates to planning the implementation, how people were attracted to engaging with the process and how this was carried out.

Stage two—understanding themes of barriers and facilitators in relation to implementation frameworks

Thematic analysis of extracted units of text revealed that barriers and facilitators were reported in similar ways across the 43 studies. This different perspective revealed six themes that demonstrated how researchers reported barriers and facilitators:

-

1.

Non-adherence/adherence.

-

2.

Perception of the intervention indicating a barrier/facilitator.

-

3.

Attrition.

-

4.

Trial-related barriers/facilitators.

-

5.

Training barrier/facilitator.

-

6.

Cost barrier/facilitator.

Most studies reported barriers (n = 30) and or facilitators (n = 29) related to adherence. Studies reported what study participants, carers and healthcare staff involved in delivering the intervention thought about the intervention, either negatively (n = 30) or positively (n = 35). Typically reported as “acceptability”, this theme was mapped to different constructs dependant on whether it was the patient’s perceptions or the clinicians. Patients’ reports of acceptability were mapped to “patient needs and resources” and clinicians’ perceptions mapped to “knowledge and beliefs of the intervention” in CFIR. Under half of studies (n = 17) described reasons for attrition and trial-related issues. Table 4 indicates which studies reported barriers and facilitators under which theme and the supplementary materials provide greater detail from each study alongside the themes together with a summary of the reported complex intervention.

Discussion

The aim of this review was to identify the barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of complex health interventions in adults with long-term neurological conditions (LTNC) in developed countries. This comprehensive and rigorous review resulted in the identification of 43 studies from eight countries, describing the problems and facilitators involved with the delivery of complex interventions.

Even though some researchers did not intend to focus on reporting barriers and facilitators, it was possible to identify these implementation issues as previously reported by Siemonsma [36]. Over 200 determinants (barriers and facilitators) were reported for interventions related to exercise, home-based rehabilitation, psychosocial and educational interventions, constraint-induced movement therapy, motor imagery, memory aids, self-management and continence training. Interventions were delivered to over 4000 people with LTNCs by over 400 rehabilitation health professionals: mostly occupational therapists and physiotherapists.

In order to be able to clearly describe implementation, barriers and facilitators were mapped onto constructs of two implementation research frameworks; CFIF [32] and CFIR [33]. Barriers and facilitators were mapped to most constructs, demonstrating they are wide ranging, which strengthens the usefulness of the frameworks, as others have found [34, 35, 90,91,92].

Six themes were identified that reflect how researchers currently tend to report barriers and facilitators. Most researchers reported barriers and facilitators in terms of “adherence” and “perceptions of the intervention”. Adherence can refer to the recipient and provider of an intervention and is regarded as an important determinant of intervention effectiveness [32]. Adherence (facilitator) and non-adherence (barrier) to intervention protocols were reported in 29 and 30 studies (respectively), indicating that researchers tend to routinely report these aspects. Most units of text within “adherence” were mapped to “facilitation strategies” in the CFIF, where positive strategies were undertaken to improve adherence to the intervention. Being able to identify these facilitators within existing studies will be helpful in the design of future similar studies.

The theme addressing “perceptions of the intervention” was reported positively and negatively in 35 and 30 studies (respectively) and primarily associated with the intervention’s acceptability. Acceptability is a broad term used to report a range of perceptions about an intervention from the perspective of recipients (people with LTNCs) and providers (clinicians) [93] but is also an important implementation issue [93, 94]. The concept of “acceptability” is important when considering responsiveness to an intervention [95] and especially so when moving from single studies to larger multi-centre trials where poor acceptability of interventions may affect their implementation [93]. Identifying issues related to intervention acceptability may help to reveal why some studies experienced implementation issues.

The reporting of both “perceptions of the intervention” and “adherence” is often required by publications. They indicate high-quality reporting and may explain the frequency of coverage in this review [96]. More recent guidance, for example; The TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) Checklist [97], Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) [98] and Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2) [99] recommend this. These guidelines demonstrate the general agreement amongst many researchers that reporting the context of intervention delivery within research is important, but the increasing number of guidelines that now overlap is not necessarily more help [100].

As part of the process of developing new health interventions, researchers are encouraged to carry out process evaluations and feasibility studies that provide the opportunity to explore implementation issues comprehensively before progressing onto phase III trials [3, 101]. In the future, it is expected that more journals will encourage publication of process evaluations and implementation research, underpinned by a relevant theoretical framework. By doing so, researchers will need to become more aware of implementation research, resulting in increased reporting.

Overall, more barriers than facilitators were reported and links between determinants and recommendations for future implementation strategies are rarely made. This has been found elsewhere [18]. This may be because most studies did not explicitly set out to identify factors affecting the intervention implementation and may not have been aware of implementation research frameworks to support their identification or reporting. Identifying facilitators as well as barriers provides a useful starting point to develop and test implementation strategies. It is recommended that to understand the implementation of complex interventions for LTNCs, studies should identify barriers, facilitators, potential implementation strategies and methods to test them. This would promote understanding between determinants and the overall context [102].

The mapping process revealed 6 constructs without any barriers or facilitators mapped to them. These gaps relate to the quality of intervention delivery, design quality and packaging of the intervention, external (peer) pressure to implement the intervention and the process aspects of implementing the intervention (engaging, executing and reflecting). There may be several reasons for these gaps.

The interventions investigated in these studies may not have tapped these constructs, but it is unlikely that implementation of complex interventions for people with LTNCs went entirely smoothly, encountering no issues. The mapping procedure conducted in this review may have failed to assign some determinants to the appropriate constructs. However, it is more likely that researchers were unaware of the breadth of the context that “barriers and facilitators” emanate from or that these could inform future intervention implementation [30]. Historical publishing requirements, as mentioned above, may also have limited reporting. Whatever the reason, it is important to recognise these gaps have only been revealed by using implementation frameworks. In the future, researchers are recommended to use an implementation framework when examining implementation issues; if certain constructs in a framework do not attract determinants, this should be made explicit and explained. It is important for research teams to be aware of implementation research theory and to build this into study designs. Without measuring barriers and facilitators, it may be difficult to explain why an intervention works or not, and the chances of predicting success and designing strategies to ensure success are limited [30].

Whilst this review has shown it is possible to identify barriers and facilitators from studies that did not primarily intend to report them and then map them to two implementation research frameworks, studies using an implementation research framework were more logical and simplified the identification of barriers and facilitators. There is currently no standardised method for collecting or analysing data about implementation barriers and facilitators [30]. But the fact that it was possible to map multiple barriers and facilitators to so many constructs of CFIF and CFIR serves to validate their utility [103]. The two frameworks used in this review offer little guidance on how to identify barriers and facilitators. The lack of differentiation between implementation theories, models and frameworks [30, 33, 104] adds to the difficulty in choosing one to use dependent on the study [30, 105, 106]. But being uninformed does not seem a suitable reason for risking repeating known implementation mistakes [30, 106, 107]. CFIR has online resources sharing knowledge aimed at developing tools [108]. To progress this work further, researchers should engage in moving theories forward to include practical guidance and tools [30, 94, 107].

Trial-related issues are described less often in the older papers in this review. The Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on process evaluations of complex interventions reinforces that rehabilitation researchers should examine and report barriers and facilitators throughout intervention development [109] and not leave this until translation into practice. There is acknowledgement of differences between implementing rehabilitation into clinical practice compared with a trial, but little is known about the research setting [16, 84]. Even though the MRC guidance on developing complex interventions and process evaluations has been widely cited over the past 9 years, the rehabilitation research community has been slow to respond. The more recent papers included in this review who have examined the research context in more detail may reflect increased awareness of the value of describing what affects intervention delivery and other trial aspects such as preparing a site ready for recruitment, training therapists to deliver an intervention and understanding the perceptions of a wider range of stakeholders, not only patients receiving the intervention.

By addressing the implementation of rehabilitation early in an intervention’s development, trialists can provide assurance about intervention effectiveness by demonstrating that it has been implemented as planned, thus preventing type III errors [29]. The return on investment into rehabilitation research and outcomes for people with LTNCs may improve by understanding the implementation of interventions early on. Eventually, this may help policy makers and commissioners understand how an intervention will work in a range of contexts with different populations and improve their confidence to warrant funding new interventions [27, 28].

One main strength of this review is the thorough and systematic search methodology. Using broad inclusion criteria to maximise the identification of published research strengthened the process. The review has focussed on a range of important implementation issues that have not been included in previous literature reviews for LTNCs. However, more stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria could have distinguished more formal research from other studies based in clinical settings.

Theoretical frameworks from implementation research underpinned the review and facilitated in-depth, two-stage data analysis. Using the CFIF and CFIR frameworks together allowed an understanding of how they relate to each other. Parallels and variances in language used were revealed, which inform theoretical development [33, 110]. The use of two complementary theoretical frameworks, each with a different focus on implementation, provided structure to the analysis [105, 111] and helped to ensure the results are relevant across settings [111].

The team approach to this review helped to address bias through discussions and reaching consensus. The author’s background as a practising clinician was made explicit as a potential source of bias during thematic analysis and data interpretation [112].

Identifying relevant text within studies was a lengthy process because the language and definitions used were not standardised, requires subjective judgement and is open to interpretation. Other researchers could have reached a different conclusion and mapped determinants to different constructs. The findings that some constructs had no barriers or facilitators mapped to them could be because of the mapping process itself. The lack of budget for foreign language translations meant the review was limited to the English language.

Conclusions

This review has described the barriers and facilitators identified in studies implementing complex interventions for people with LTNCs. Studies adopting an implementation framework simplified the identification of barriers and facilitators, an important consideration for busy researchers. In the development of a new complex intervention, it is vital to learn from previous experiences to prevent unnecessary repetitions of implementation failure at both trial and service provision levels. Therefore, researchers and service providers should be cognizant of and utilise implementation theory and implementation frameworks to guide the identification and reporting of implementation issues in future studies. Clinicians should look to studies that have utilised implementation theory and make use of reported strategies for overcoming implementation issues.

The information gleaned in this review was used in an implementation strategy, where occupational therapists were trained to deliver a new early specialist vocational rehabilitation intervention for TBI in the NHS in England, in a feasibility randomised controlled trial [24, 113]. The barriers and facilitators identified in this review helped to inform trainers and mentors in supporting the therapists [114]. Other researchers may also find the information useful to inform study design and understand, for instance, what support might be required by clinicians delivering an intervention.

Recommendations for researchers

-

Investigate barriers and facilitators early in the development of rehabilitation interventions.

-

Use an implementation framework to guide the investigation.

-

Explore the findings of similar research to avoid unnecessary repetition of implementation issues.

-

Describe barriers and facilitators in sufficient detail for others to make useful comparisons.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- LTNC:

-

Long-term neurological condition

- CFIF:

-

Comprehensive framework for implementation fidelity

- CFIR:

-

Consolidated framework for implementation research

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

- VR:

-

Vocational rehabilitation

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

References

Cucciare MA, Curran GM, Craske MG, Abraham T, McCarthur MB, Marchant-Miros K, et al. Assessing fidelity of cognitive behavioral therapy in rural VA clinics: design of a randomized implementation effectiveness (hybrid type III) trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–9.

Robb SL, Burns DS, Docherty SL, Haase JE. Ensuring treatment fidelity in a multi-site behavioral intervention study: implementing NIH behavior change consortium recommendations in the SMART trial. Psycho-oncology. 2011;20(11):1193–201.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J. 2008;337:a1655.

Medical Research Council. A framework for the development and evaluation of RCT’s for complex intervention to improve health. London: Medical Research Council; 2000.

Comptroller and Auditor General. Services for people with neurological conditions: progress review. London: National Audit Office; 2015.

Neurological Alliance. Neuro numbers. London: Neurological Alliance; 2014.

Royal College of Physicians, National Council for Palliative Care, British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. Long-term neurological conditions: management at the interface between neurology, rehabilitation and palliative care. London: Royal College of Physicians; 2008. 20080515 DCOM- 20080814. Contract No.: 1470-2118 (Print).

World Health Organisation. Rehabilitation: WHO.Int; 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/rehabilitation/en/.

Department of Health, editor. National Framework for long term neurological conditionsDepartment of Health, editor.: The Stationary Office; 2005.

Department of Health and Social Care. The NHS Outcomes Framework 2020 [updated 20 Aug 20]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/ci-hub/nhs-outcomes-framework.

Wade D. Rehabilitation--a new approach. Overview and part one: the problems. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29(11):1041–50.

Eccles MP, Armstrong D, Baker R, Cleary K, Davies H, Davies S, et al. An implementation research agenda. Implement Sci. 2009;4:18.

Hawe P. Lessons from complex interventions to improve health. Ann Rev Publ Health. 2015;36(1):307–23.

Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N. Changing the behavior of healthcare professionals: the use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:107–12.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implementation Science. 2012;7(1):1-17.

Luker JA, Craig L, Bennett L, Ellery F, Langhorne P, Wu O, et al. Implementing a complex rehabilitation intervention in a stroke trial: a qualitative process evaluation of AVERT. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:52.

Walker MF, Hoffmann TC, Brady MC, Dean CM, Eng JJ, Farrin AJ, et al. Improving the development, monitoring and reporting of stroke rehabilitation research: consensus-based core recommendations from the stroke recovery and rehabilitation roundtable. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(5):472–9.

Bosch M, Van Der Weijden T, Wensing M, Grol R. Tailoring quality improvement interventions to identified barriers: a multiple case analysis. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13(2):161-8.

Colditz GA. The promise and challenges of dissemination and implementation research. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Ioannidis JPA, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, Khoury MJ, Macleod MR, Moher D, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet. 2014;383(9912):166–75.

Graham CW, West MD, Bourdon JL, Inge KJ, Seward HE, Graham CW. Employment interventions for return to work in working-aged adults following traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2016;6:i-133.

Saltychev M, Eskola M, Tenovuo O, Laimi K. Return to work after traumatic brain injury: systematic review. Brain Inj. 2013;27(13-14):1516–27.

Phillips J, Radford KA. Vocational rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury: what is the evidence for clinical practice? Adv Clin Neurosci Rehabil. 2014;14(5):14–6.

Radford K, Sutton C, Sach T, Holmes J, Watkins C, Forshaw D, et al. Early, specialist vocational rehabilitation to facilitate return to work after traumatic brain injury: the FRESH feasibility RCT. Health Technol Assess. 2018;22(33):1–124.

Deshpande P, Turner-Stokes L. In: Tyerman A, Meehan M, editors. BSRM Survey of vocational rehabilitation services available to people with acquired brain injury in the UK; 2004.

Playford E, Radford K, Burton C, Gibson A, Jellie B, Sweetland J, et al. Mapping vocational rehabilitation services for people with long term neurological conditions: summary report. London: Department of Health; 2011.

Bonell C, Oakley A, Hargreaves J, Strange V, Rees R. Assessment of generalisability in trials of health interventions: suggested framework and systematic review. Br Med J. 2006;333(7563):346.

Shiel-Davis K, Wright A, Seditas K, Morton S, Bland N, MacGillivray S, et al. What works Scotland evidence review: scaling-up innovations. Scotland: What Works Scotland; 2015.

Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237-56.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):1–13.

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(2):337–50.

Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40.

Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):1-15.

Connell L, McMahon N, Harris J, Watkins C, Eng J. A formative evaluation of the implementation of an upper limb stroke rehabilitation intervention in clinical practice: a qualitative interview study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:90.

Masterson-Algar P, Burton CR, Rycroft-Malone J, Sackley CM, Walker MF. Towards a programme theory for fidelity in the evaluation of complex interventions. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(4):445–52.

Siemonsma P, Dopp C, Alpay L, Tak E, van Meeteren N, Chorus A. Determinants influencing the implementation of home-based stroke rehabilitation: a systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(24):2019–30.

Fleuren MAH, Paulussen TGWM, Van Dommelen P, Van Buuren S. Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. International J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(5):501–10.

Brady MC, Jamieson K, Bugge C, Hagen S, McClurg D, Chalmers C, et al. Caring for continence in stroke care settings: a qualitative study of patients’ and staff perspectives on the implementation of a new continence care intervention. Clin Rehabil. 2015;30(5):481–94.

Brady MC, Stott DJ, Norrie J, Chalmers C, St George B, Sweeney PM, et al. Developing and evaluating the implementation of a complex intervention: using mixed methods to inform the design of a randomised controlled trial of an oral healthcare intervention after stroke. Trials. 2011;12:168.

Mittman BS. Implementation science in healthcare. In: Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, editors. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9.

Holmes J, Radford K, Logan P. Barriers and facilitators in implementing complex health interventions (rehabilitation) with adults who have long-term conditions.: PROSPERO; 2015. [CRD42015020423]. Available from: Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42015020423.

The World Health Organisation. Rehabilitation: key facts; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rehabilitation.

United Nations Statistics Division. UNSD — methodologyhttps://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/: United Nations [30 Mar. 2017]. Available from: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/; 2017.

Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):1–9.

Gould NJ, Lorencatto F, Stanworth SJ, Michie S, Prior ME, Glidewell L, et al. Application of theory to enhance audit and feedback interventions to increase the uptake of evidence-based transfusion practice: an intervention development protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):92.

Braun SM, van Haastregt JC, Beurskens AJ, Gielen AI, Wade DT, Schols JM. Feasibility of a mental practice intervention in stroke patients in nursing homes; a process evaluation. BMC Neurol. 2010;10:74.

Cup EHC, Pieterse AJ, Hendricks HT, Van Engelen BGM, Oostendorp RAB, Van der Wilt GJ. Implementation of multidisciplinary advice to allied health care professionals regarding the management of their patients with neuromuscular diseases. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(9):787–95.

Nanninga CS, Postema K, Schonherr MC, van Twillert S, Lettinga AT. Combined clinical and home rehabilitation: case report of an integrated knowledge-to-action study in a Dutch rehabilitation stroke unit. Phys Ther. 2015;95(4):558–67.

Prick A-E, de Lange J, van’t Leven N, Pot AM. Process evaluation of a multicomponent dyadic intervention study with exercise and support for people with dementia and their family caregivers. Trials. 2014;15:401.

Speelman AD, van Nimwegen M, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Evaluation of implementation of the park fit program: a multifaceted intervention aimed to promote physical activity in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Physiotherapy. 2014;100(2):134–41.

Sturkenboom IH, Graff MJ, Borm GF, Veenhuizen Y, Bloem BR, Munneke M, et al. The impact of occupational therapy in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27(2):99–112.

Sturkenboom IHWM. Nijhuis-van der Sanden MWG, Graff MJL. A process evaluation of a home-based occupational therapy intervention for Parkinson’s patients and their caregivers performed alongside a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(12):1186–99.

Tielemans NS, Schepers VP, Visser-Meily JM, van Haastregt JC, van Veen WJ, van Stralen HE, et al. Process evaluation of the Restore4stroke self-management intervention ‘plan ahead!’: A stroke-specific self-management intervention. Clin Rehabil. 2016;30(12):1175–85.

van Bruggen-Rufi CHM, Hogenboom M, Vink AC, Achterberg WP, RAC R. Process evaluation of a randomized controlled trial studying the effect of music therapy in patients with Huntington’s disease. J Mem Disord Rehabil 2(1):1005.

Van’t Leven N, Graff MJL, Kaijen M, de Swart BJM, Rikkert M, Vernooij-Dassen MJM. Barriers to and facilitators for the use of an evidence-based occupational therapy guideline for older people with dementia and their carers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(7):742–8.

Veenhuizen RB, Kootstra B, Vink W, Posthumus J, van Bekkum P, Zijlstra M, et al. Coordinated multidisciplinary care for ambulatory Huntington’s disease patients. Evaluation of 18 months of implementation. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:77.

Allison R, Dennett R. Pilot randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of additional supported standing practice on functional ability post stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(7):614–9.

Bovend’Eerdt TJ, Dawes H, Sackley C, Izadi H, Wade DT. An integrated motor imagery program to improve functional task performance in neurorehabilitation: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(6):939–46.

Gage H, Grainger L, Ting S, Williams P, Chorley C, Carey G, et al. Specialist rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s disease in the community: a randomised controlled trial. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014;2(51). https://doi.org/10.3310/hsdr0251083.

Gibson JME, Thomas LH, Harrison JJ, Watkins CL. Stroke survivors’ and carers’ experiences of a systematic voiding programme to treat urinary incontinence after stroke. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(9-10):2041–51.

Horton S, Lane K, Shiggins C. Supporting communication for people with aphasia in stroke rehabilitation: transfer of training in a multidisciplinary stroke team. Aphasiology. 2016;30(5):629–56.

Jarvis KA. Occupational therapy for the upper limb after stroke: implementing evidence-based constraint induced movement therapy into practice [thesis (Ph.D.)]. Newscastle-under-Lyme: Keele University; 2016.

Sadler E, Sarre S, Tinker A, Bhalla A, McKevitt C. Developing a novel peer support intervention to promote resilience after stroke. Health Social Care Commun. 2017;25(5):1590–600.

Thomas LH, French B, Burton CR, Sutton C, Forshaw D, Dickinson H, et al. Evaluating a systematic voiding programme for patients with urinary incontinence after stroke in secondary care using soft systems analysis and normalisation process theory: findings from the ICONS case study phase. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014;51(10):1308–20.

Douglas NF. Supporting speech-language pathologist evidence-based practice use: a mixed-methods study in skilled nursing facilities within the promoting action on research implementation in health services framework [Health & Mental Health Treatment & prevention 3300]. South Florida: ProQuest Information & Learning US; 2014.

Kinnett-Hopkins D, Motl R. Results of a feasibility study of a patient informed, racially tailored home-based exercise program for black persons with multiple sclerosis. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;75:1–8.

Learmonth YC, Adamson BC, Kinnett-Hopkins D, Bohri M, Motl RW. Results of a feasibility randomised controlled study of the guidelines for exercise in multiple sclerosis project. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;54:84–97.

Mahoney EK, Trudeau SA, Penyack SE, MacLeod CE. Challenges to intervention implementation: lessons learned in the bathing persons with Alzheimer’s disease at home study. Nurs Res. 2006;55:S10–6.

Merlo AR, Goodman A, McClenaghan BA, Fritz SL. Participants’ perspectives on the feasibility of a novel, intensive, task-specific intervention for individuals with chronic stroke: a qualitative analysis. Phys Ther. 2013;93(2):147–57.

Morrison SA, Backus D. Locomotor training: is translating evidence into practice financially feasible? J Neurologic Phys Therapy. 2007;31(2):50–4.

Mackenzie C, Muir M, Allen C, Jensen A. Non-speech oro-motor exercises in post-stroke dysarthria intervention: a randomized feasibility trial. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(5):602–17.

Nicholson S. The development and testing of a behavioural change intervention to increase physical activity, predominantly through walking, after stroke: University of Edinburgh; 2017.

Simpson R, Simpson S, Wood K, Mercer SW, Mair FS. Using normalisation process theory to understand barriers and facilitators to implementing mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with multiple sclerosis. Chronic Illn. 2018;15(4):306–18.

Bentley B, O’Connor M, Kane R, Breen LJ. Feasibility, acceptability, and potential effectiveness of dignity therapy for people with motor neurone disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96888.

Haines TP, Hill KD, Bennell KL, Osborne RH. Additional exercise for older subacute hospital inpatients to prevent falls: benefits and barriers to implementation and evaluation. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(8):742–53.

Wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, Lord S, Taylor M, Gitlin L, et al. A feasibility study and pilot randomised trial of a tailored prevention program to reduce falls in older people with mild dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:89.

Demers M, McKinley P. Feasibility of delivering a dance intervention for subacute stroke in a rehabilitation hospital setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(3):3120.

Halle M-C, Le Dorze G, Mingant A. Speech-language therapists’ process of including significant others in aphasia rehabilitation. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2014;49(6):748–60.

Richardson J, DePaul V, Officer A, Wilkins S, Letts L, Bosch J, et al. Development and evaluation of self-management and task-oriented approach to rehabilitation training (START) in the home: case report. Phys Ther. 2015;95(6):934–43.

Barzel A, Ketels G, Stark A, Tetzlaff B, Daubmann A, Wegscheider K, et al. Home-based constraint-induced movement therapy for patients with upper limb dysfunction after stroke (HOMECIMT): a cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(9):893–902.

Voigt-Radloff S, Graff M, Leonhart R, Hüll M, Rikkert MO, Vernooij-Dassen M. Why did an effective Dutch complex psycho-social intervention for people with dementia not work in the German healthcare context? Lessons learnt from a process evaluation alongside a multicentre RCT. BMJ Open. 2011;1(1).

Johannessen A, Povlsen L, Bruvik F, Ulstein I. Implementation of a multicomponent psychosocial programme for persons with dementia and their families in Norwegian municipalities: experiences from the perspective of healthcare professionals who performed the intervention. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014;28:749–56.

Brady MC, Stott DJ, Norrie J, Chalmers C, St George B, Sweeney PM, et al. Developing and evaluating the implementation of a complex intervention: using mixed methods to inform the design of a randomised controlled trial of an oral healthcare intervention after stroke. St George: Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit, Glasgow Caledonian University, Glasgow, United Kingdom; 2011.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149–58.

Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Grieve R. Fair tests of clinical trials: a treatment implementation model. Adv Behav Res Ther. 1994;16(1):1–29.

May C. A rational model for assessing and evaluating complex interventions in health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6(1):1–11.

Grol RWM. Implementatie. In: Effectieve verbetering van de patiëntenzorg. [effective improvement of patient care]. Maarssen: Elsevier Gezondheidszorg; 2006.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33.

Augustsson H, Schwarz UV, Stenfors-Hayes T, Hasson H. Investigating variations in implementation fidelity of an organizational-level occupational health intervention. Int J Behav Med. 2015;22(3):345–55.

Graham-Rowe E, Lorencatto F, Lawrenson JG, Burr J, Grimshaw JM, Ivers NM, et al. Barriers and enablers to diabetic retinopathy screening attendance: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):134.

Ilott I, Gerrish K, Booth A, Field B. Testing the consolidated framework for implementation research on health care innovations from South Yorkshire. J Eval Clin Pract. 2013;19:915–24.

Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):88.

Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2011;38(2):65–76.

Sermeus W. Modelling process and outcomes in complex interventions. In: HI RDA, editor. Complex interventions in health: an overview of research methods. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015. p. 111–20.

Hoffmann TC, Erueti C, Glasziou PP. Poor description of non-pharmacological interventions: analysis of consecutive sample of randomised trials. Br Med J. 2013;347.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687.

Ogrinc G, Davies L, Goodman D, Batalden P, Davidoff F, Stevens D. SQUIRE 2.0 (standards for QUality improvement reporting excellence): revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:986–92.

Möhler R, Köpke S, Meyer G. Criteria for reporting the development and evaluation of complex interventions in healthcare: revised guideline (CReDECI 2). Trials. 2015;16(1):204.

Davies L, Ogrinc G, Mosher H, Stevens DP, Davidoff F, Armstrong G, et al. Re: standards for reporting implementation studies (StaRI) statement (letter to the editor). Br Med J. 2017;356:i6795.

Richards DA, Hallberg IR. In: HI RDA, editor. Complex interventions in health: an overview of research methods. Abingdon: Routledge; 2015.

Lau R, Stevenson F, Ong BN, Dziedzic K, Treweek S, Eldridge S, et al. Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: systematic reviews of reviews. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–39.

Liang S, Kegler MC, Cotter M, Emily P, Beasley D, Hermstad A, et al. Integrating evidence-based practices for increasing cancer screenings in safety net health systems: a multiple case study using the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–12.

Bhattacharyya O, Reeves S, Garfinkel S, Zwarenstein M. Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions: fine in theory, but evidence of effectiveness in practice is needed. Implement Sci. 2006;1.

Flottorp SA, Oxman AD, Krause J, Musila NR, Wensing M, Godycki-Cwirko M, et al. A checklist for identifying determinants of practice: a systematic review and synthesis of frameworks and taxonomies of factors that prevent or enable improvements in healthcare professional practice. Implement Sci. 2013;8(35). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-35.

The Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group., (ICEBeRG). Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006;1(1):1–8.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:24–34.

CFIR Research Team. Consolidated framework for implementation research (CFIR) wiki. Ann Arbor: Center for Clinical Management Research; 2016. Available from: http://cfirguide.org/wiki/index.php?title=Main_Page.

Moore G, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonnell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance. London: MRC; 2014.

Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, Damschroder L. A systematic review of the use of the consolidated framework for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):1–13.

McEvoy R, Ballini L, Maltoni S, O’Donnell CA, Mair FS, MacFarlane A. A qualitative systematic review of studies using the normalization process theory to research implementation processes. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):1–13.

Bowling A. Research methods in health: investigating health and health services: McGraw-Hill education (UK); 2014.

Radford K, Phillips J, Jones T, Gibson A, Sutton C, Watkins C, et al. Facilitating return to work through early specialist health-based interventions (FRESH): protocol for a feasibility randomised controlled trial. Pilot Feasib Stud. 2015;1(1):24.

Holmes J, Phillips J, Morris R, Bedekar Y, Tyerman R, Radford K. Development and evaluation of an early specialised traumatic brain injury vocational rehabilitation training package. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(11):693–702.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Doctoral studies funding from the University of Nottingham School of Medicine and Division of Rehabilitation and Ageing, the University of Nottingham Impact Campaign LifeCycle 3 and the UK Occupational Therapy Research Fund. The funding bodies had no involvement in the design of the study or collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JH carried out the review and writing the paper. KR and PL were involved in the screening and selection of included studies and in writing the paper. RM was involved in writing the paper. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

No ethical approval was required. However, this study was part of the doctoral studies of J Holmes and as such was approved by the University of Nottingham.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Holmes, J.A., Logan, P., Morris, R. et al. Factors affecting the delivery of complex rehabilitation interventions in research with neurologically impaired adults: a systematic review. Syst Rev 9, 268 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01508-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-020-01508-1