Abstract

Discourse about the L’Aquila trial in Italy has overlooked the many different roles that laws play within risk governance. For volcanic risk governance, laws not only create the duty holders, beneficiaries and the relationships between them (the stakeholders) and the duties and rights (the stakes) but also dictate the acceptable standards of safety and wellbeing (the ultimate rewards).

Within any legal regime, certain court cases will attract a high public profile. They can serve a very helpful role by opening the black box of societal risk management so that robust and candid scrutiny of the past can lead to better management of the future. With such cases, the goal of the competent observer is to advance beyond debate about contested factual details of the past (the noise of what happened) and, by process of induction, to identify wider issues of principle and precedent upon which to make reasoned improvements (the signal to guide what should happen differently in the future and why).

The generic characteristics of law-based regulatory regimes are identified because they can be treated as ‘constants’ which do not change, or do so only very slowly over time. Accordingly, these aspects are highly relevant to long-term risk governance. More ephemeral case-specific factual issues often remain contested and, accordingly, receive less attention here. Significant recent court cases, including L’Aquila, are framed by process of deduction within a generalised legal infrastructure in order to identify the root causes of the apparent status quo of risk governance. This forensic approach is vital not only to identify the legal responsibilities of societal risk managers and the managerial risks that they face and their causes but also to consider possible mitigation strategies.

We identify the critical issue of managerial risk vulnerability related to ‘standard equivocality’ which is the absence of commonly recognised standards for hazard communications to risk decision makers. This absence may result from the lack of regulation of relevant practices and practitioners. We offer some recommendations to fuel debate not only within those science groups that reacted to the L’Aquila case but also the scientific community as a whole. Finally, we argue that checklists represent a rational and methodical way to develop acceptable practice standards focussed upon the difficult risk mitigation choices that are made by civil protection authorities and at-risk individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discourse about the L’Aquila trial warrants careful reflection and addition. To some commentators the trial is “highly controversial” whilst to others it is better described as “so-called” (Alexander 2014a, Alexander 2014b; Cartlidge 2015; Fioritto 2014; Gabrielli and Di Bucci 2014; Lauta 2014a, 2014b; Notaro 2014; Simoncini 2014). To date, the discourse has generally been confined narrowly to a single criminal case isolated from its wider governance context. The predominant focus has been upon the trial process and the prosecutor’s allegations about past practices. This paper refers to, and builds upon, recent initiatives to learn from the event. By framing the trial in a wider context, it is linked to the processes of societal and managerial risk governance for the purpose of enabling future risk managers to change their practices and avoid similar difficulties.

We describe the structural constants of a generalised legal infrastructure. Framed within that infrastructure, recent cases including L’Aquila are used to identify those parts of a social risk governance process that lead to managerial risks.

The L’Aquila case was the prime catalyst for our research and its role should not be misunderstood or overstated. Our focus is on the implications of legal processes that involve detailed analysis of the practices of scientists at work and not the disputed detail and merits of particular cases. In relation to L’Aquila, this paper therefore deliberately attempts to avoid all controversial issues regarding the characteristics of the Italian criminal justice system, the merits of and motivations behind the prosecution, the alleged roles and culpabilities of the defendants, the sentences and penalties imposed at trial, the outcome of the appeals and the initial reactions of many scientific communities.

No attempt is made to duplicate the institutional dimension considered by Scolobig et al. (2014) and the helpful distinction they make between framing emergency problems in terms of public safety rather than public control. In support of this distinction, it is worth noting that the stated aim of most, if not all, legal regimes regulating the risks of natural hazards is safety and not control. By way of illustration, in Japan, the Disaster Countermeasures Basic Act 1997 expressly states an objective of protecting the national territory, the life and limb of citizens and their property. In Indonesia, the stated aim of Disaster Management Law 24/2007 is providing protection for life and livelihood including protection against disasters in order to attain public welfare.

We describe how laws shape and support societal risk governance and analyse the material aspects of recent court cases. We argue that managerial risks, just like societal risks, must be assessed for the purpose of ascertaining what measures, if any, are required for their mitigation. It is our hope that this paper will assist managerial risk assessments by identifying: (1) duty holders (exposures); (2) societal risk non-compliance (vulnerabilities); and (3) risk mitigation strategies. Table 1 summarises a common approach to the governance of societal and managerial risks in the context of volcanic hazards.

Laws provide the essential infrastructure of risk governance (the governance playing field), define the duty and rights holders and the relationships between them (the players, the positions and dimensions of the goals, and the rules of the game) and the empowered regulators (the referees with red and yellow cards).

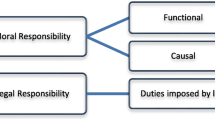

The generic characteristics of law-backed regulatory regimes are identified because they can be treated as ‘constants’. They are formal, persistent and predictable (Wilkinson 2013) changing only slowly over time. Accordingly they are highly relevant to risk management, the paramount purpose of which is to manage the future. Case-specific factual issues, which are in effect past ‘variables’, receive less attention because: (1) often they are and will continue to be disputed and controversial; and (2) they are likely to represent an unreliable basis for the design and management of the future unless very similar facts are presented in the same jurisdiction. The roles, constants and variables, referred to above, are illustrated in a generalised legal infrastructure in Fig. 1.

The facts of an individual court case are invariably interesting as they offer a snapshot of the past. However, they remain largely irrelevant to any forensic analysis of the legal scrutiny process itself and the subsequent identification and consideration of its constituent parts. Adopting a counterfactual approach, the facts, whether they are agreed or disputed, represent only one realisation of what could have happened (Woo 2010, 2011, 2015).

We adopt a working assumption that there is a perception in many scientific communities that, for a number of reasons, managerial risks are increasing. Social science discourses are used to discuss the possible consequences of these perceptions upon managerial risk behaviours, including those of “Getting Better” and “Getting Smarter”, and to consider possible managerial risk mitigation options.

General approach, terminology and methodology

General approach

Firstly, in an ‘Observations’ section we provide a very brief summary of selected aspects of the L’Aquila case. For reasons that are explained, a wholly neutral description has been attempted. A number of other recent court cases are also briefly described and framed within the generalised legal infrastructure illustrated in Fig. 1.

In a section entitled ‘Discussion: Laws - What roles do they fulfil?’, we provide an overview of the role of laws in the governance of natural hazards with particular reference to the governance of future volcanic risks.

In the next section, ‘The implications of the observations’, we refer to the profound implications of the observed court cases and describe the fundamental regulatory function of court cases and in particular the influence of legal liability on societal risk governance.

Lastly, in a ‘Recommendations’ section, we consider the issue of ‘professionalism’ and identify the absence of regulation and the significance of ‘standard equivocality’. We review steps that may represent the earlier stages of informal (i.e. unregulated) ‘collective organisation’ before linking a number of recommendations to specific aspects of the legal scrutiny process.

Terminology

Risk governance

While governance is a complex concept that is subject to varying definitions (Power 2007; Renn 2008; International Risk Governance Council IRGC 2005, 2007, 2009), it is generally accepted that it encompasses an array of organisations, practices and ideas (Rothstein et al. 2012) which change over time. The following definition is embraced.

Governance is the sum of the many ways individuals and institutions, public and private, manage their common affairs. It is a continuing process through which conflicting or diverse interests may be accommodated and co-operative action may be taken. It includes formal institutions and regimes empowered to enforce compliance, as well as informal arrangements that people and institutions either have agreed to or perceive to be in their interest (Commission on Global Governance 1995).

Risk governance includes all attempts to manage the three constituent variables of risk including steps to mitigate volcanic hazards (there are very few successful examples of this), to reduce the exposure of people, assets etc. and to reduce their vulnerability when exposed. This expression is adopted not only as an analytic term to describe a web of actors and activities but also for ‘normative’ purposes. Risk governance has a set of definable ‘good’ qualities which provide for the effective integration of the key components of how risks are handled by risk stakeholders (Walker et al. 2010), 12; International Risk Governance Council IRGC 2009a).

Societal and Managerial risks

A distinction is made here between the management of: (1) first order ‘societal risks’ faced by citizens; and (2) second-order risks to the legitimacy of societal risk managers and their “rules and methods of decision making” as a result of internal and external control, scrutiny and accountability which we call ‘managerial risks’ (Power 2007).

Reflecting the “extent to which regulation is itself subject to regulation”, managerial risks are diverse and include “reputational risks, legal liability and risks of failing to meet performance [political and spending] targets” (Power 2007). They have been described in terms of a pervasive fear of the possible negative consequences of being responsible and answerable; of being required to produce decidability in the face of the un-decidable (Power 2007). Rothstein et al. (2012) refer to the difficulties for decision makers caused by the “fear of public pillory”.

The class of regulators, quasi-regulators and scrutineers includes governments, the law, organised interest groups, the press and media (both mass and social) and the public. Regulators are invariably given very extensive investigatory powers and, in many jurisdictions, scrutineers are assisted by wide ranging Freedom of Information laws. They are likely to have a range of different perceptions of and approaches to risk assessment and management.

In this paper managerial risks faced by individuals are called ‘professional risks’ and those faced by government bodies and other entities ‘institutional risks’.

Blame, blame-risks and blame-related behaviours

Hood (2011) notes the expression ‘managerial risks’ does not have a clearly established meaning and adopts the expression ‘blame risk’ identifying at least two components of blame, which is the act of attributing something considered to be bad or wrong to some person or entity. The first is “some element of perceived and avoidable harm or loss – something is seen as worse for some person or group than it could have been if matters had been handled differently.” The second is “some attribution of agency – that harm was avoidable because it was caused by the omission or commission by some identifiable individual or organisation.” Both of these components can vary according to the point in time when avoidable loss/harm and agency/responsibility are perceived. As a social process, ‘blaming’ must involve at least two sets of actors, namely blame makers (those who do the blaming) and blame takers (those who are on the receiving end). Hood (2011) notes “Professionals will care about blame if they think it will diminish their reputations in ways that could damage their careers or produce expensive lawsuits over malpractice.”

For Felstiner et al. (1980) blaming - what they call ‘naming’ - is a necessary precursor for ‘claiming’ in the sense of seeking some remedy from the individual or entity held to be responsible. The claiming can range from demands for explanation to monetary compensation, the resignation or dismissal of those who are culpable or official expressions of sorrow ranging from corporate apologies or more or less drastic acts of contrition by individual officeholders (Hood 2011).

It has been said that “the more closely we are watched, the better we behave” and that this “indisputable truth…is one of the corner-stones of political science” (Bentham and Quinn 2001). Three ways of behaving better, or at least differently, as a reaction to real and/or perceived managerial risk increases, are “Get Better” at societal risk management, “Get Smarter” at managerial risk management or “Get a Lawyer” Footnote 1(Hood 1986, Hood 2001; Rothstein et al. 2006).

Hood (2011) identifies three types of blame-avoidance strategy. One is ‘policy strategies’, which is the selection of policies and operating routines to minimise risk of individual or institutional liability or blame. Variants of ‘policy strategies’ include: (1) ‘individualisation’ in which the ‘agency’ dimension of blame, to which we have already referred, is shifted rather than reduced or prevented; (2) ‘protocolisation’ or “playing it by the book”, and (3) ‘abstinence’ or ‘just say no’, in other words, choosing not to provide the services that attract blame or have the potential to do so. Later, we will give relevant examples of all three.

Standard equivocality

Throughout this paper, reference will be made to ‘standard equivocality’ (Rothstein 2002; Hood 1986). This is the absence of commonly recognised standards (norms) capable of guiding, measuring and evolving acceptable practice.

Methodology

Law

We undertook a detailed review of legislation in a representative sample of jurisdictions that host active volcanos. This simple methodology was adopted to create a generalised legal infrastructure that can be applied readily to any regulatory regime that relies upon a legal and administrative infrastructure with duties and rights supported by scrutiny arrangements to enforce and protect them. Recent court cases were thereafter reviewed to enable their framing within that infrastructure.

For the sake of brevity and clarity, we have not attempted to show all the legal sources that contributed to the creation of the generalised legal infrastructure, referred to above. Five ‘Additional files’ are used which contain a small number of selected legislative provisions that illustrate the general principles we wish to identify and describe.

Risk governance

Risk issues are handled separately and differently. Since the early 1980′s a linear model (also described as either technocratic or Red Book) has been used for the governance of many societal risks (NRC 1983, 1996; Renn 2008). This model, which is criticised by many authors (e.g. Fischer 2000; Pielke 2004; Donovan & Oppenheimer 2012), starts with the characterisation of hazard, proceeds to the integration of that variable with societal variables of exposure and vulnerability, and culminates in risk management decisions. In the absence of the general acceptance of a better model, such as the more cyclical, iterative, transparent and inclusive model advocated by some commentators (e.g. Eden 1998; Fischer 2000, Fischer 2010, Renn 2008; Brown 2009, Jasanoff 2005; Donovan 2014) we suggest that the same 1980's linear approach can and should be used for the governance of managerial risks.

An analogue for the probability of the onset of a societal hazard (i.e. for the likelihood of an explosive eruption of a volcano) might be the probability of a regulator or regulatory process scrutinising a duty holder’s standards of societal risk governance. We suggest that this parameter is changing as the likelihood of scrutiny is increasing. Recent cases may also indicate that the reach and intensity of scrutiny may also be increasing encouraged by a move towards more open and transparent governance styles in many jurisdictions.

We draw an analogy between the ‘exposure’ condition of societal risks, caused by the spatial and physical parameters of a natural hazard and often delineated in societal risk maps, and the ‘exposure’ condition of managerial risks, caused by the characteristics of the managerial hazards and in particular the ‘spatial’ reach of the long arm of the law within a legal infrastructure.

People situated in a societal risk zone are exposed and, as a consequence, their vulnerability to the natural hazard in question becomes relevant and has to be assessed. By using a generalised legal infrastructure, societal risk duty holders can be readily identified. They are the entities and individuals exposed to the circumstance (the governance of societal risks) that causes managerial risks. Entities that are not duty holders in law have no enforceable responsibilities and, accordingly, are not exposed.Footnote 2 Adopting the same systematic approach to both societal and managerial risks, as all duty holders in law are exposed per se, the next step is to assess their vulnerabilities. This involves a robust and candid assessment of the extent to which societal risk duties of care have been fulfilled. We discuss the difficulties of achieving and maintaining societal risk compliance later.

In summary, managerial risks, just like societal risks, must be assessed for the purpose of ascertaining what measures, if any, are required for their mitigation. Table 1 summarises commonalities in the governance of societal and managerial risks in the context of volcanic hazards.

Observations

Six cases are referred to below and, for ease of reference, they are listed in Table 2 and illustrated in Fig. 1. In both Table 2 and Fig. 1 national cases are shown in blue; international in red.

The L’Aquila case

On 6 April 2009 at about 03:32 Central European Time, a 6.3 Mw earthquake occurred near L’Aquila, Italy resulting in over 300 fatalities, over 1,500 injured people and approximately 20,000 buildings being rendered uninhabitable. A related legal process, described by Lauta (2014a) as “a spectacular penal case”, opened up the Black BoxFootnote 3 (Latour 1987) of societal risk management and scrutinised at length the behaviour of a number of officials, most of whom were scientists (Alexander 2014a). It was alleged that the defendants were members of the Commissione Nazionale per la Previsione e Prevenzione dei Grandi Rischi (CGR) tasked to assess major risks and to inform that decision making process and the public of these risks (Lauta 2014b). They were indicted for and found guilty of involuntary manslaughter. Lengthy prison sentences and large financial penalties were handed down at the first instance trial. Appeals against both conviction and sentence were pursued by all the defendants. Six were acquitted and the sentence of the sole convicted defendant was reduced.

Some of the actual details of the L’Aquila tragedy and case can be found elsewhere (Alexander 2014a, Alexander 2014b; Gabrielli & Di Bucci 2014; Scolobig et al. 2014; Lauta 2014a; Lauta 2014b; Simoncini 2014; Notaro 2014; Fioritto 2014). However, as some ‘published facts’ are still contested, detailed discussion of such issues is deliberately omitted here to avoid distraction from our main theme.

The L’Aquila case concerned an alleged breach of a national lawFootnote 4 imposing a criminal law duty of care. Purportedly the trial was about the alleged consequences of public officials (duty holders) misleading the public (rights holders) with incomplete, imprecise and contradictory information (Alexander 2014a). As a matter of legal logic, the trial judge must have made in respect to all seven defendants; (1) a finding of law that the duty holders had a legal duty of care to provide to the public information that was “complete”, “precise” and “clear”; (2) a finding of fact that, in breach of this duty, that they did not; and (3) a finding of factual causation that this breach led to losses of life. On appeal, this reasoning was clearly upheld in respect of the sole remaining convicted defendant.

Other recent court cases in context

In the case of Garcés in Chile in December 2013, the Chilean Supreme Court ordered state institutions (duty holders) to pay compensation to several claimants (rights holders) for breach a national law that imposed a civil law duty of care (Duffield 2013; Trujillo 2013).

Garcés case, Chile

Mario Segundo Ovando Garcés was a resident of Santa Clara, Talcahuano. On 27 February 2010, in the wake of 8.8 magnitude earthquake, he heard the Regional Governor dispel the risk of a tsunami on a local radio station and decided not to evacuate his home. 20 minutes later a tsunami killed Mario and over 300 other people.

The Chilean Navy runs the Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service (SHOA). SHOA admitted after the tsunami that it had made errors and given unclear information to government officials who issued an alert, withdrew it, only to reissue it after the event. The Supreme Court of Chile held government agencies responsible for Mario’s death and awarded his dependants over US$ 55,000 compensation.

In a criminal law prosecution relating to the same tsunami, Chile’s National Prosecutor’s office is prosecuting, for involuntary manslaughter and other less serious offences, seven public officials including Carmen Fernández, a former director of the National Emergency Agency, and Patricio Rosende, a former Under-Secretary of the Interior (Bonnefoy 2013).

Nineteen people died in the volcanic eruption of Soufriere Hills, Montserrat on 25 June 1997. In 1997 Montserrat was a British Dependent Territory (now an Overseas Territory) and the British government had ultimate responsibility for the island’s welfare. In late 1998 an inquest concerning those deaths was held by a Coroner sitting with five jurors. It heard evidence from 52 witnesses over a period of 2 months. An inquest is a judicial enquiry into sudden or unexplained causes of death and is required to make findings of fact regarding, inter alia, the injury causing each death and the circumstances in which that injury was sustained. (Montserrat 1998, 1999; Section 12 Coroner's Act 1950).

Sonfriere Hills Inquest, Montserrat

In all 19 deaths, the jury decided that the cause of death was “the natural catastrophe of volcanic eruption/pyroclastic flow”.

The evidence established that people had returned to their homes in an Exclusion Zone to avoid deplorable conditions in public shelters. Many of the people killed were farmers who had returned to visit, live or work in the Exclusion Zone despite widespread knowledge that it was unsafe. They were caught in and could not escape from a sudden surge/eruption of pyroclastic flow. A recorded contributory cause of 9 deaths was the failure of the authorities (both local and British) to provide alternative lands in safe areas for farmers displaced from the Exclusion Zone. For 4 other deaths, it was the continued operation of the airport despite elevated volcanic activity in the days immediately preceding the 25 June eruption. In 1 case, the jury stated conditions in the public shelters were so deplorable that the deceased had refused to return to them after his initial experience.

One of the functions of an Inquest (Section 12, Coroner’s Act 1950) is to make recommendations to appropriate authorities to assist in the avoidance in future of circumstances which may be prejudicial to the health or safety of the public. The Coroner made a number of recommendations about the need for more permanent affordable housing for about 400 people in overcrowded shared accommodation and many more in involuntary exile overseas. The British government’s response, over 40 months after the start of the crisis, was described as pathetic, unimaginative, grudging and tardy. Recommendations were also made regarding deplorable conditions in public shelters and ways of improving the provision of risk information to members of the public.

New Zealand offers a very good example of a post facto regulatory investigation following a fatality on Raoul Island (New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment website).

Raoul Island Fatal Inquiry, New Zealand

In March 2006 a ranger employed by the NZ Department of Conservation was killed whilst taking samples from Raoul Island’s crater-lake. The volcano suddenly and violently erupted and the water level of the lake rose 4 m as a result. New Zealand’s relevant regulator, the Department of Labour, investigated the incident and in particular the actions of two duty holders, namely the deceased’s employer, the Department of Conservation (DOC), and the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Science (IGNS) which had been contracted to carry out scientific monitoring work.

No criticism was made of the duty holders but the regulator recommended that the duty holders improve the safety aspects of scientific monitoring and investigate the automated monitoring of high risk locations.

In the absence of relevant national laws, or when national laws are inadequate, ineffective or unenforced, there is room for the intervention of international law.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) has taken the lead and we suggest here that in time the Inter-American Court of Human Rights will follow. The European Convention of Human Rights (EConHR) lays down a positive obligation on States to take appropriate steps to safeguard the lives of citizens within their jurisdiction. Article 2 (1) EConHR provides that “Everyone’s right to life shall be protected by law. No one shall be deprived of his life intentionally save in the execution of a sentence of a court following his conviction of a crime for which this penalty is provided by law”.

In the context of the management of natural hazards, the most important case involving Article 2 arose in 2008. Budayeva and others v Russia (2008) ECHR 15339/02 concerned a mudslide. In this case the EHCR considered principles which had been applied in Oneryildiz v Turkey (2004) to a man-made hazard - an industrial risk or dangerous activity such as the operation of a waste site. They were subsequently adopted in Kolyadenko & others v Russia (2012) in respect natural flash floods.

Budayeva and others v Russia

The town of T was situated in a mountain district. Two tributaries passed through it and were known to have associated mudslides. A mud collector and a dam were constructed in order to protect T. The dam was seriously damaged by a mud and debris flow in August 1999, so funds were requested to construct observation posts to warn of mudslides until it could be repaired, and to carry out certain emergency works to the dam.

Those measures were never implemented. A number of mudslides occurred in July 2000, killing eight residents, including the first applicant’s husband, and destroying the applicants’ homes.

It was decided to dispense with a criminal investigation into the circumstances of the death of the first applicant’s husband, and claims of compensation by the first applicant and others were refused on the basis that a mudslide of such exceptional force could neither have been predicted nor stopped. However, the applicants were granted substitute housing and a lump-sum emergency allowance.

The applicants complained to the ECHR, inter alia, that the authorities had violated the substantive limb of Article 2 of the EConHR. The first applicant asserted that the authorities were responsible for the death of her husband and she and the other applicants asserted that the authorities had failed to take appropriate measures to mitigate the risks to their lives posed by natural hazards.

The Court concluded that the relevant authorities were aware of the mudslides (the hazards) and their capacity to cause devastating consequences (the risks). There was no ambiguity about the scope and timing of the work that needed to be performed (the risk mitigation actions). After 1999, risk mitigation was not given proper consideration by the decision makers and budgetary bodies (the duty holders) and there was no functioning early warning system. State responsibility for the deaths had never been investigated. Each applicant was awarded compensation.

The EHCR determined that the obligation in Article 2 entails, above all, a primary duty on the State to put in place a clear legislative and administrative framework designed to provide effective deterrence against threats to the right to life. It applies in the context of any activity, whether public or not, in which the right to life may be at stake and extends not only to industrial risks and dangerous activities but also actions and omissions to control natural hazards.

In cases of Oneryildiz v Turkey (2004), Budayeva v Russia (2008), and Kolyadenko and others v Russia (2012), to which we have already referred, and also Kats & others v Ukraine (2008) and Rantsev v Cyprus & Russia (2010) the EHCR determined that there is a positive obligation: (1) ex-ante to take substantive regulatory measures to manage risks; and (2) ex-post facto to ensure that any risk eventuated fatalities are followed by a public investigation. In relation to the later, procedures must exist for identifying not only shortcomings in the ex-ante regulatory measures but also any errors committed by those responsible (i.e. duty holders). If there are any shortcomings and the infringement of the right to life was not intentional, it is not necessary for criminal proceedings to be brought in every case. It may satisfactory to make available to the victims civil law remedies (either alone or in conjunction with a criminal law remedy) enabling any responsibility of the parties concerned to be established and any appropriate civil redress, such as an order for the payment of damages, to be obtained.

The positive obligations of EConHR State duty holders under the ECHR are summarised in Fig. 2.

Other cases (Guerra v Italy 1998, Vilnes v Norway 2013) have relied upon the ECHR Article 8 right of an individual to respect for their private life. It has been determined that there is a positive obligation for States to “provide access to” essential information enabling individuals to assess risks to their health and safety. That obligation might in certain circumstances also encompass a duty actually to ‘provide’ such information.

Discussion: Laws – What roles do they fulfil?

Making natural hazards, such as volcanos, the formal subject of risk governance

As we recognise in this paper that risk is multi-variate, being the convolution of variables of hazard, exposure and vulnerability, it follows that volcanic hazards only become volcanic risks, properly so called, with the existence of social exposures and vulnerabilities. The three variables are convolved because they are, to some extent, concomitant and ‘mutually conditioning’ (Bankoff et al. 2004, 38).

Many risks are, in whole or in part, recurring social manifestations (i.e. human-made phenomena) with negative consequences (Lauta 2014a; Lauta 2014b). In many cultures, particularly western cultures, they are no longer perceived as the consequences of external forces occurring independently of society (in other words, events that are either divine or inherent in nature) and being insusceptible to mitigation by society. Accordingly, they are now positioned within, and have become the responsibility of, the institutions and stakeholders of relevant social communities (Lauta 2014a; Lauta 2014b). These human-made risks are perceived to be susceptible to regulation with the objective of achieving their effective mitigation. In this context, regulation is formal, structured and active management pursuant to primary and secondary laws. By way of illustration, the population of Naples has greatly increased since 1944 and many would argue that the resulting increase in volcanic risk exposure is human-made and capable of regulation.

Low probability-high impact risks pose a particular challenge for legislators. In fact there are three related challenges, namely scientific uncertainty, a low likelihood of occurrence and significant societal consequences. Whilst the elevated consequences of these risk call for some level of regulation, the intrinsic uncertainty and low probability of their occurrence makes it difficult to review the evidentiary scientific justification, to assess costs and benefits and to identify the means by which the goals can be pursued (Simoncini 2013).

In the absence of a tragedy, it is difficult to measure the performance of law-backed societal risk governance by the usual measures of: (1) economy (e.g. value for money) for input and process; (2) efficiency (e.g. quality delivered on time) for process and output; and (3) effectiveness for output and outcome. The indicators of outcome (the intended and unintended results) of the integrated governance system will be related to the impacts on and the consequences for public good, safety, security, health and welfare but it will be a challenge for any related targets (e.g. benchmarks and performance standards) to be SMART - Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timed (OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 2002; OECD et al. 2002; Basher 2006).

By contrast, in a fact-finding process of scrutiny after a tragedy, the use of SMART targets may become more practicable. It may be possible to measure hazard characterisation outputs against planned targets for timely delivery, user-friendliness, outcome-focus and temporal/spatial/intensity forecast accuracy. Based upon findings of fact, it may be feasible to quantify the resulting risk-mitigation impact measured in lives and assets saved.

Notwithstanding these challenges, many jurisdictions have national laws that attempt to regulate the management of risks arising from natural hazards. Many reflect the shift in paradigm, at both international and national levels, from focussing on post-facto, reactive response (the phases of emergency response and post-disaster longer term recovery) to ex-ante, pro-active risk management and mitigation (the phase of planning and preparedness) (UN SC-DRR 2009). Although we suspect that emergency response may still dominate thinking and funding in some jurisdictions, these national laws are unlikely to diminish in number and/or reach in the light of: (1) the emerging international law governance norms to which we have already referred; (2) the IFRC and UN law checklist, to which we will refer later, and (3) the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–30 which specifically prioritises prevention before response and recovery (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies IFRC and United Nations Development Programme 2015, 9; United Nations International Strategy for Disaster UN/ISDR 2015).

The creation of risk governance infrastructures

As illustrated in Fig. 1, national laws tend to identify, authorise and fundFootnote 5 risk governance bodies (e.g. government departments & agencies, public corporations) and public officials (e.g. individuals such governors, mayors, prefects & village heads) within a coherent legal and administrative framework, in other words, a risk governance infrastructure. These laws often use and build upon existing entities within existing administrative frameworks that have multi-level national, regional, district, municipal etc. political divisions and subdivisions.

In some jurisdictions, formal legal infrastructures anticipate and rely upon less formal structures and relationships at a local level near at-risk communities. For example, in Ecuador the risk governance infrastructure relies upon the engagement and commitment of local representatives (e.g. chiefs and elders) and volunteers, such as hazard wardens/monitors, for both hazard data gathering and risk mitigation.

In some jurisdictions, such as Italy, laws favour the imposition of duties upon individuals rather than impersonal legal entities such as government departments/agencies and public companies. Legal duties may be founded upon an individual having effective decision-making powers and control over financial resources rather than upon an individual holding a particular title or occupying a particular post (Bergman et al. 2007).

These infrastructures can be complex, confusing, fragmented and multi-level. They are often the creations of multiple sets of national primary (enabling) and secondary (detailed implementing) legislation supplemented as necessary by further provisions at ministerial, inter-ministerial, regional, provincial and local levels of government. An additional file shows this in more detail [see Additional file 1].

Occasionally additional specialised bodies are established (e.g. emergency management agencies, research/monitoring institutes and volcano observatories) with the creation of statutory roles to be filled by appointed individuals. An additional file shows this in more detail [see Additional file 2].

The creation of duty holders, duties of care and rights holders

National laws allocate to bodies and individuals (duty holders) high level management functions with responsibilities (duties of care) which are owed to the particular classes of people for whose benefit the duties were created (rights holders). In some jurisdictions, general disaster management obligations are also imposed on ‘the community’ (i.e. members of the public) and business institutions. During the course of an emerging period of hazard unrest, the relevant duty holders may change as defined duties are transferred from one duty holder to another - sometimes as a result of changing hazard or risk characterisations. These duties of care can be framed in a wide variety of ways. They may relate to general health and safety not specifying any risk creator (a particular hazard, natural or otherwise) or may be more specific identifying a particular hazard (flooding, earthquakes etc.).

Rights holders may be given the right to a safe and healthy environment, and to be represented, consulted or engaged in risk decisions and/or given information. Additional rights may be given to certain categories of persons due to special vulnerabilities and/or the influence of social structures and practices. These categories may include women, the very poor, older persons, children and people with disabilities (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies IFRC and United Nations Development Programme 2015).

An additional file shows this in more detail [see Additional file 3].

There are two main types of duty of care which are called here respectively ‘functional’ and ‘goal-setting’. Functional duties dictate the fulfilment of a particular role (e.g. a duty to undertake monitoring, to prepare plans and programmes for emergency preparedness or to provide emergency preparedness communications and warnings). Goal-setting duties require the achievement of an outcome (e.g. a duty to ensure the safety and wellbeing of identified rights holders). Not even within the highly regulated field of occupational health are these safety goals absolute (i.e. unqualified). The imposition of an unrealistic absolute duty would give rights holders a theoretical guarantee of health and safety within a risk-free environment.

As a general rule, ‘qualified’ duties of care are therefore laid down. These duties represent democratic statements or mandates of ‘acceptable’ or ‘optimal’ risk after mitigation and express a rational trade-off between safety and riskFootnote 6 (Hood & Rothstein 2001; Rothstein 2014). Rothstein (2014) notes “After all, what is an acceptable risk other than a euphemistic boundary between an acceptable adverse outcome and an unacceptable failure”. Compliance with qualified duties inevitably requires duties holders to perform a risk-focussed cost/benefit analysis and a test of proportionality.Footnote 7

Laws rarely, if ever, attempt to dictate, in either general or more detailed terms, the societal risk management arrangements that will be required to either fulfil a functional role or achieve a stated safety outcome. In practice, an assessment of societal vulnerability has two main stages. Firstly, the nature and scope of duties of care must be identified and delineated. This is essentially a matter of law and involves the legal interpretation of primary and secondary legislation and, if relevant, case law. Secondly, it is necessary to identify the actions that the duty holder should take to fulfil those duties. This is far more difficult. Competent lawyers can describe the safety function or outcome required in law – in football terms the dimensions and position of the goal. However, they can offer very limited guidance regarding the practical measures that the competent societal risk manager will need to take to achieve legal compliance (i.e. how actually to get the ball over the goal line). This general approach seems to have been adopted by the three appeal judges in the L’Aquila appeal hearing. It has been reported that the prosecutor attempted to show that the defendants had flouted specific duties imposed on them by law as members of the Commissione Nazionale per la Previsione e Prevenzione Dei Grandi Rischi but the Appeal Court judges argued that the law was too vaguely defined to allow such an approach. Instead, they said, “the experts should have been judged on how well they adhered to the science of the time” (Cartlidge 2015).

In the case of food standards and occupational health and safety standards, it is common for national laws to set up government agencies to carry out research, to set performance standards and offer approved codes of practice or authoritative guidance. By contrast in respect of volcanic hazards, at both international and national levels, there appear to be neither: (1) law-based performance standards offering guidanceFootnote 8 to societal risk managers; or (2) law endorsed self-regulatory regimes such as those that frequented the early stages of food regulation.

Within the ‘goal-setting’ legislative approach, referred to above, it is implicit that there is an obligation on duties holders to establish the nature and suitability (i.e. the legal adequacy) of their societal risk management arrangements. This difficult justification will usually be done post-facto, in other words, only after the risk outcome (perhaps a disaster properly so-called) is known and legal consequences are already being considered (Simoncini 2011). The justification will cover, but will not be limited to, the arrangements that were necessary for the planning, organisation, control, monitoring and review of societal risk mitigation measures. To complete our footballing analogy, post-facto legal processes are analogous to slow motion TV replays, in full view of partisan onlookers and experts with hindsight, which determine what has happened, whether or not a goal has been scored and, if not, why not and what affect any missed goal had on the final score (i.e. whether legal compliance has actually been achieved and, if not, why not and what the consequences should have been if compliance had been achieved).

‘Standard equivocality’, which is the absence of commonly recognised standards (norms), is likely to exist in the absence of clear ‘legal’ requirements, approved codes of practice or guidance. The resulting challenges faced by duty holders are: (1) to find or design authoritative standards or benchmarks to steer their societal risk management arrangements; and thereby (2) increase their chances of fulfilling their societal risk duties of care and achieving legal compliance; and thereby (3) minimise their vulnerability to managerial risks.

Rothstein (2001) and Hood (1986) have noted that, in the absence of commonly agreed and practical principles or methodologies by which compliance can be measured (‘standard-unequivocality’), process compliance is difficult to monitor and process non-compliance is difficult to enforce. Other obstacles to monitoring, surveillance and enforcement include inherent scientific uncertainty, a dynamic state of scientific knowledge, lack of expertise within regulatory agencies and often complex and fragmented multi-level infrastructures. Donovan and Oppenheimer (2014) notes that Possekel (1999) and Clay et al. (1999) both identified complexities in governmental structures as presenting major challenges for the managing volcanic eruptions on Montserrat.

The creation of powers

Traditionally, national laws have granted defined ‘authorities’ to government duty holders backed by administration, protection and intervention powers (ordinary, extra-ordinary and emergency). Governance, with an emphasis more on control than protection, has often been achieved by the exercise of authority using linear “coercion and enforcement” (Rosenau et al. 2004; Walker et al. 2010). An additional file shows this in more detail [see Additional file 4].

The creation of regulators, enforcement powers and scrutiny venues

Laws often establish, resource and empower regulators to monitor the performance of duty holders and to take enforcement actions, including prosecutions, against them, if necessary. Examples of regulators include the Labour Standards Agency in Japan, the Department of Labour Health and Safety Service in New Zealand and the Occupational Safety and Health Agency in the United States of America. These regulators often have very wide powers similar to and sometimes exceeding those of police forces. They include the power to enter premises, to investigate and inspect, to acquire and preserve evidence and to serve notices.

Laws provide the formal scrutiny venues (courts, tribunals etc.) and related procedures for: (1) the ex-ante pro-active enforcement of duties of care by regulators, generally health and safety agencies; and (2) the ex-post facto reactive scrutiny of events, the identification of duty holders, the assessment of what happened and what should have happened and, if appropriate, the imposition of sanctions and/or the granting of remedies. The later procedures are required at a national level to comply with the international law ex-post facto obligations in Fig. 2.

In March 2015 the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the United Nations (UN) Development Programme issued the pilot version of “The checklist on law and disaster risk reduction”. It encourages accountability mechanisms within legislation for failure to fulfil risk governance responsibilities. In particular it advocates laws: (1) to establish public reporting or parliamentary oversight mechanisms and transparency requirements for government entities tasked with risk governance responsibilities; (2) to give a mandated role to the judiciary in enhancing accountability; (3) to provide enforceable incentives for compliance and disincentives for non-compliance; and (4) to establish legal and/or administrative sanctions (as appropriate) for public officials individuals and businesses for a gross (“particularly egregious”) failure to fulfil their duties (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies IFRC and United Nations Development Programme 2015, 16).

In a few known jurisdictions (e.g. USA, Canada and the Philippines) laws also regulate to varying degrees the qualification, licensing and registration of geologists and the practice of geology per se. An additional file shows this in more detail [see Additional file 5].

Implications of the observations

Recent court cases

The implications of the six cases, in Fig. 1, are profound. For natural hazards it is now clear that not only ‘national’ laws but also ‘international’ laws create duty holders with specific risk governance obligations. The IFRC and UN law checklist, to which we have already referred, recognises and supports this position (International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies IFRC and United Nations Development Programme 2015). It has even been said that today the development of disaster prevention is not only a moral obligation but also a human right (Lauta 2014a).

Tragedies resulting from natural hazards may result in: (1) the risk of compensation payments from civil law claims (Budayeva and Garcés); (2) the risk of penal sanctions from criminal prosecutions (L’Aquila and Fernandez); and/or (3) the risk of factual findings (Sonfriere Hills Montserrat and Raoul Island New Zealand Island).

In respect of the L’Aquila trial, Lauta (2014a, 147) argues that it reflects not only the potential collateral damage of natural hazards becoming the subject of societal risk management but also the resulting possibility of related responsibility and politico-legal issues. He also identifies the potential of scapegoating, the risk of applying hindsight causality and the difficulty in placing responsibility in a complex setting of individuals and institutions.

Lauta (2014b) notes:

The L’Aquila order is not extraordinary, medieval, or an incident we can rightly consider an isolated Americanised fluke – rather, it is part of the recognition that disasters are increasingly spheres of social control and thereby potential injustice. Disasters form part of a contingent and violent world, but they no longer serve as free get-out-out-of-jail-cards from the responsibility of professional neglect.

Court cases open the Black Box of societal risk governance

As required by emerging international law, national laws create and will continue to create rigid and permanent infrastructures, legal and administrative frameworks, within which societal risk governance is undertaken. In a functioning democracy, national laws should reflect the extent to which members of the public consider it both practicable (feasible) and reasonable (when considered in the context of available time and finite national, regional and local resources) to manage the risks of natural hazards in order to safeguard the lives, livelihoods and property of individuals and communities. Their implied, if not express, aim is to achieve a rational balance between safety and risk.

Laws create holders of duties and rights (stakeholders) and enforceable relationships between them. Some of these duties and relationships may be contractual (i.e. the product of voluntary negotiation) rather than being imposed by mandatory legislation. For example, a government agency such as a volcano observatory may agree to provide at a price forecasts and data for the private operators in the tourist or aviation sectors. Between different jurisdictions international treaties may create enforceable obligations to coordinate hazard assessments and risk mitigation strategies. By way of example, the Instituto Geofisico in Ecuador exchanges data and coordinates hazard communications with its neighbour Colombia’s OVSP-SGC in respect of Volcan Chiles-Cerro Negro.

Tribunals and related procedures, such as the post-facto procedures set out in Fig. 2, are provided to ensure duties are performed and rights are protected. Legal liability plays a fundamental regulatory function. Simoncini (Simoncini 2013, Simoncini 2014 Footnote 9) notes the allocation of liability not only makes possible post-facto criminal law sanctions and civil law remedies to penalise inadequate societal risk management (it creates the stick) but also provides an ex-ante indirect incentive for good risk management (it produces the carrot).

Lauta (2014a) identifies and attempts to address a conflict between the functions respectively of the stick and the carrot in distributing risk, blame and responsibility fairly and expeditiously in society. He refers to the “need to address the challenge of developing legal systems able to facilitate the perceived injustice of the victims of a disaster and simultaneously not to endanger the overall societal aim of creating the most effective disaster response system”.

Ten years ago, Aspinall & Sparks (2004) noted “the world is becoming increasingly litigious and legal cases involving scientists as expert witnesses, or even targets of civil and criminal proceedings are becoming more commonplace and more contentious”. Prophetically they said:

With a ‘blame culture’ growing in many societies, volcanologists are unlikely to escape from involvement in legal issues, since their scientific advice can have profound implications for governmental decisions that affect people’s lives. Such decisions may involve matters of life and death, severe disruption to people’s lives in a volcanic crisis, or major costs associated with compulsory evacuations.

Court cases and other scrutiny processes open in public the Black Box of societal risk governance. We refer to Fig. 1 and in particular the green lined box entitled “Actual practice to fulfil duties of care as influenced by acceptable current practice but subject to ‘standard equivocality’”. The post-L’Aquila discourse has overlooked the fact that, whilst court cases may highlight the ‘constants’ of societal risk governance, their role is not to determine what the ‘constants’ should be. This issue will have been determined already and is a question of law not fact. It is, of course, accepted that weaknesses and related improvements may be identified leading to long-term infrastructural changes and perhaps the necessity of amending legislation.Footnote 10

By contrast, the actual performance of the ‘constants’ (what actually happened?) is an ever changing ‘variable’. It is question of fact and not law. It is determined at one moment in time and compared with what was planned and/or required by law (what should have happened?). This variable forms the factual substance of individual court cases and is often the subject of intense debate.

For societal risk managers, Black Box opening is a hazard which may create managerial risks (what Hood calls blame-risks) including public pillory and legal sanctions. Recent court cases are a further reminder, albeit for many a very unwelcome reminder, that the Black Box of societal risk governance can be opened and in the future will be opened again, perhaps with greater frequency. We have already shown that in Europe (see Budayeva v Russia) an independent and thorough investigation is now a legal requirement following natural hazard fatalities.

We suggest here that a legal infrastructure of societal risk governance simplifies and even encourages the identification of the blame takers and any post-tragedy scrutiny process will readily identify and describe the circumstances of the perceived avoidable harm. The scene after a natural tragedy is therefore ripe for the processes of blaming, naming and claiming, to which we have already referred.

This growing realisation of greater scrutiny and accountability, as evidenced by the public reactions of many scientific groups to the L’Aquila case, should be used positively as an incentive for better societal risk management (i.e. for Getting Better). It should not be used negatively as an excuse to undertake blame-avoidance or blame-dissolution behaviour such as ‘defensive risk management’, a well-documented organisational rationality, in order to prioritise managerial risk management at the expense of societal risk management (i.e. for Getting Smarter) (Hood 2001, 2011; Hood & Rothstein 2000, 2001; Rothstein et al. 2006).

Gabrielli & Di Bucci (2014) commenting directly on the L’Aquila trial, refer to an accusatory approach that induces a feeling of fear of possible punishment and “is characterised by a progressive, regular adoption of behaviours that are not aimed at better managing the [societal] risk, but rather at attempting to minimise the possibility to be personally involved in a future legal controversy”.Footnote 11 This appears to be a clear warning that an accusatory approach may lead to the unintended consequence of the prioritisation of professional protection (i.e. managerial risks) before societal safety (societal risks). We have already referred to three types of blame-avoidance strategy identified by Hood (2011). One variant of policy strategies is ‘abstinence’ or ‘just say no’, in other words, choosing not to provide the services that attract blame or have the potential to do so. This strategy, expressed as the withdrawal of scientific expertise, was predicted by most L’Aquila press statements.

Interestingly, Donovan and Oppenheimer (2014) identify a pre-L’Aquila perceived need to mitigate management risks and refer to the anxiety of scientists concerning their liability, which they suggests “is clear from [Montserrat Scientific Advisory Committee] reports particularly from 2002 onwards (when there were several court cases about evacuations)”. They argue that “the formalisation of advice into the SAC was largely to gain greater protection, and SAC reports contain a disclaimer, pointing to the government’s responsibility for its decisions.”

One variant of Hood’s blame-avoidance policy strategies is ‘protocolisation’ or “playing it by the book”. The formalisation of advice into the Montserrat SAC advice might be an example of this. Another policy strategy is ‘individualisation’ in which the ‘agency’ dimension of blame, is shifted rather than reduced or prevented. A disclaimer, such as that used by the Montserrat SAC, is a device that can implement this type of strategy.

Although the L’Aquila convictions have highlighted a number of perceived managerial risks (both exposures and vulnerabilities), as we have already sought to demonstrate, no international or national legal regime will dictate, with any degree of guiding precision, ‘what should happen’-in other words the theoretical models and practical policies and arrangements required for effective hazard assessment, societal risk management and related hazard and risk communications. In the presence of ‘standard equivocality’, Getting Better is far from a straightforward response. However, we note that, in the absence of prescribed legal rigidity, there exists real freedom for risk managers to test different approaches to societal risk governance (including more complex, non-linear, multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary models) such as those described within a recent Tristan da Cunha case study (Hicks et al. 2013).

The devil (the risk of accountability and blame) therefore lies in the dynamic detail of what represents current ‘acceptable practice’ in the form of the ways and means by which legal duties can actually be fulfilled by duty holders to the required legal standard within the time and resource constraints of dynamic practice. Simoncini (2014) would describe these practices, which she considers should be known in advance (presumably in advance of any process of legal scrutiny) as “the expected level and nature of…performance”. Notaro (2014) states that the L’Aquila trial judge said (at page 91 of his judgment) that the object of the CGR’s task was expressly specified by the law (i.e. the duty of care was clearly stated) but (at pages 823 et sqq.) he was forced to determine exactly what type of conduct was effectively expected of the members of the CGR to absolve their duties in L’Aquila.Footnote 12 We have already noted that the L’Aquila appeal judges decided that the defendants had to be judged by how well they adhered to the science of the time i.e. current accepted scientific standards (Cartlidge 2015).

This devil ignited and continues to fuel post-L’Aquila debate about the merits of initiatives to recognise and record ‘practice’. Subsidiary debates are likely to revolve around; (1) the relative merits of practice norms that are labelled respectively ‘acceptable’, ‘good’ and ‘best’; and (2) the critical norms that should underpin all scientific activities and deliverables with a view to making them more relevant to and valued by civil protection authorities and at-risk individuals. Should they be recipient-focussed, process outcome-focussed, independent, objective, neutral/unbiased, value-free, and balanced?

This is not first time that these difficult issues of professional liability, competence and standards have been raised (Aspinall & Sparks 2004; Aspinall 2011). In 2004 Aspinall & Sparks (2004) commented:

What are the legal responsibilities of a volcanologist in a crisis? What comparison can be made with other areas of professional liability? Under what circumstances might a volcanologist be held accountable in court, and what standards of scientific evidence are required…What after all is ‘a professional geologist’ and how would one satisfy a court as to one’s professional standards and competence?

Recommendations

Getting Better – A Response to Black Box opening

Careful consideration should be given to mitigation options that may be available to individuals and groups of individuals in response to professional risks.

Regulation (external and self) and its implications

A starting point may be to revisit the status of those geoscientists who would answer to the description of ‘volcanologists’, and to consider whether their practices entitle them now, or rather should entitle them in the future, to be described accurately as ‘professionals’. We do not attempt a detailed critique of the respective meanings of ‘profession’ and ‘professional’. Although a wide range of meanings can be found, a number of common features emerge. Most meanings involve an occupation for which a person is especially suited, educated, trained or qualified. Others features include: (1) the development of qualification standards for entry and continuing membership; (2) the establishment or recognition of apprenticeships, training and educational resources; (3) the introduction of codes of behaviour; and (4) a degree of self-regulation and/or state regulation.

For legal purposes, it has been suggested the occupations which are regarded as professions have four characteristics namely: (1) nature of work; (2) moral aspect; (3) status; and (4) collective organisation (Powell & Stewart 2012). In relation to the first three, volcanologists undertake skilled and specialised work which is predominantly mental. It is assumed that they are committed to a high standard of service for its own sake, feel committed to certain moral or ethical principles, and consider they owe a wider duty to the community and the public at large which may on occasions transcend the duty to a particular stakeholder or their employer.

Scientists in many countries and cultures enjoy a high status by common consent. Unsurprisingly, there is a lively discourse about the importance of the status of, and levels of confidence in, scientists and the extent to which risk managers as a class are trusted in the context of risk communication (Renn & Levine 1991; Siegrist & Cvekovich 2000; Earle 2004; Haynes 2005; Paton 2008; Renn 2008; Haynes et al. 2008; Barclay et al. 2008; Crosweller 2009; Bird et al. 2010; Paton et al. 2010; Crosweller & Wilmshurst 2013; Wachinger et al. 2013; Simoncini 2014). However, unlike say health professionals, accountants and lawyers, scientists are not usually given any privileges by law such as a monopoly to practice in a defined service sector (e.g. the monopolies evident in medicine, dentistry, actuarial science, civil engineering, architecture, accountancy and law).

In most jurisdictions (the Philippines and most states of the USA and Canada being known exceptions) geoscientists, including but not limited to geologists and volcanologists, are neither regulated nor licensed. The practice of geology is not defined, given a special status, or regulated. In short, individuals without any relevant qualifications or experience whatsoever can describe themselves as ‘geologists’. With no restrictions, they can practice geology, prepare geological reports and give advice. We are not saying that unregulated practitioners, per se, are incompetent but note there is no easy way to determine their status, experience or competence by reference to recognised objective independent standards.

Geologists may seek voluntary membership of one or more of nearly 300 geological societies and institutes around the world (Geology.com website).Footnote 13 Members are invariably bound by the entity’s constitution, by-laws and codes that commonly cover conduct, ethics and mineral reporting. The European Federation of Geologists (EFG) has a Code of Ethics that, in common with many other codes, addresses not only general principals but also relationships with a number of other stakeholders including the general public community (i.e. society), other geologists, employers and clients. We agree that “these codes do not spring from the work being regulated – they are imposed externally by the expectations of society at large” (Allen 2014). One of the benefits of membership may be easier compliance with title regulation formalities such as those in Alaska.

The EFG’s Code states that “the practice of geology is a profession for those who possess the necessary qualifications and/or professional experience recognised by their appropriate national body or under the law, and whose living comes essentially from such work” (emphasis added). We suggest here that it may be both ambitious and misleading to assume that, other than in very few countries, national bodies or laws exist that recognise “necessary qualifications and/or professional experience”. We noted earlier that the USA, Canada and the Philippines are known exceptions to the general rule of a total absence of ‘external’ regulation of geologists and geology.

Some scientific societies openly acknowledge the importance of compliance with the ‘law’ and ‘relevant standards’. By way of example, the Royal Society of New Zealand’s Code of Professional Standards and Ethics in Science, Technology and the Humanities (Royal Society of New Zealand 2012) states “a member must only claim expertise commensurate with their qualifications and fields of competence and must follow investigative and work practices which conform to recognised national and international standards [emphasis added]. Members must “have regard to the requirements, work practices and ethical standards of any relevant international organisation [emphasis added]”.

Other bodies, such as the International Association of Volcanology and Chemistry of the Earth’s Interior (IAVCEI), may not have a formal code but instead may offer guidance on conduct. The report entitled “Professional conduct of scientists during volcanic crisesFootnote 14” issued in 1999 by IAVCEI’s Subcommittee for Crisis Protocols (Newhall et al. 1999, Newhall et al. 2000 Geist & Garcia 2000) is a rare,Footnote 15 if not unique, example of an attempt to offer authoritative practice guidance based on past eventsFootnote 16 and an extensive literature review. The 1999 Report referred to Peterson’s very comprehensive and candid 1988 critique of the behaviour of volcanologists which includes a robust call for them to examine themselves, their roles and behaviours (Peterson 1988, 1996). With reference to the earlier issue of ‘moral aspect’, the stated guiding principle of the said report was “that during volcanic crises, volcanologists’ highest duty is to public safety and welfare”. In answer to some criticisms of the 1999 report (Geist & Garcia 2000), Newhall et al. (2000) outlined some of reasons for written standards. They stated:

We should also ask the rhetorical question, ‘Are codes of conduct ever necessary?’ In our list of references cited, readers can find quite a number of codes of conduct. Our scientific world functions best when we trust each other, and are trusted by those around us. It seems to us, as well as to many scientific academies and professional societies of the world, that written standards and or goals help to build and maintain that trust.

Conferment of a more senior status of voluntary membership, such as that of ‘Fellow’, may involve consideration of academic qualifications, relevant expertise and competence in a specialist area, and participation in continuing professional development with activities related to the development of the individual’s professed areas of expertise. Some bodies, such as the Geological Society of London (GSOL), recognise the competence of individual members in a specific field of geological science through their validation as a ‘Chartered Geologist’ or ‘Chartered Scientist’. In July 2014 the GSOL reported that chartership was gaining momentum “across the profession” and, as a result, it was receiving a growing number of applications (e.g. 45 in November 2013) (Geoscientist 2013a; Geoscientist 2013b).

We conclude that most geoscientists involved in the governance of volcanic risks do not belong to a ‘collective organisation’. By ‘collective organisation’ we mean an independent self-regulating professional association) which regulates admission, standards and other matters relating to their ‘practice’ as opposed to their initial and continued ‘membership’ of, or ‘status’ within, the organisation itself.

We accept that volcanologists working for national government agencies may have access to and be bound to follow established standards, policies and procedures to guide their operational practices. We differentiate between how volcanologists should operate by reason of their contractual employment or engagement by a particular employer, usually a government agency, and how they should practise by reason of their professed ‘status’ or ‘calling’ as competent volcanologists. In a perfect world, there would be no conflict between contractual standards and objective independent standards.

By way of theoretical context, Rothstein et al. (2006) describe an ‘early stage’ societal risk governance environment with few pressures from internal and external scrutiny. During this stage, the controls or accountability pressures on the management of societal risks are relaxed or non-existent, such as is often the case in the early stages of regulation or slack self-regulatory regimes. Under such conditions, in the absence of mechanisms for challenge or even observation, societal risk management behaviours and even failures present relatively low managerial risks. Thus, there are few incentives to proceduralise societal risk governance activities. Instead, such activities tend to be ad hoc, methodologically diverse and determined by contingent organisational pressures and ways of working.

In summary, most volcanologists are currently subject to neither ‘external’ nor ‘self’ regulation, the hallmarks of ‘professionalism’. On close formal scrutiny, they may currently struggle to describe themselves as ‘professionals’. This is very much more than a purely academic issue. The absence of not only external regulation but also self-regulation by means of collective organisation appears to have led to a low understanding and perception of managerial risks by many scientific communities. This is evidenced by their reactions to the professional risk exposures and vulnerabilities laid bare during the L’Aquila case. We suggest that as a probable consequence, and as predicted in theory (Rothstein et al. 2006), many processes of societal risk governance appear to be ad hoc, methodologically diverse and to lack any formal systematic protocol. Jordan et al. (2011) refer to the standardisation of operational procedures being in a nascent stage of development. This has led to the ‘standard equivocality’ referred to above.

Collective organisation

Steps have already been taken at the 2013 Volcano Observatory Best Practices Workshop – Communicating HazardsFootnote 17 under the aegis of IAVCEI, the World Organisation of Volcano Observatories (WOVO) and the Global Volcano Model network (GVM) to discuss international references for hazard communication and wider risk management practices.

In September 2014 at the Cities on Volcanos 8 conference,Footnote 18 IAVCEI set up a new Commission for Volcanic Hazards and Risk. Hazard communication was identified as a main theme with the specific tools of hazard mapping and alert levels (status of volcano activity levels) being identified for particular attention by dedicated working groups.

Within the new Commission, there will be a Taskforce on Crisis Protocols and Best Practices charged specifically with developing guidelines and protocols to help scientists who are involved in managing major natural hazards to develop a better understanding of their role, responsibilities and liabilities and their relationships to government and civil authorities.

IAVCEI is also discussing whether to leave the International Union for Geodesy and Geophysics (IUGG).Footnote 19 With direct reference to L’Aquila, one of the many arguments given by IAVCEI’s Committee for leaving IUGG, and becoming an independent, autonomous learned society, is greater freedom to lobby governments directly on specific issues and to protect proactively scientists involved in hazard assessment and mitigation (IAVCEI 2012–2014).

It is worth noting that, in the future, it is IAVCEI’s intention to remain the pre-eminent international volcanological society by: (1) organising conferences, workshops etc.; (2) representing the interests of its profession and member scientists; and (3) continuing to be the principal international reference organisation on policy and commentary relating to volcanological research, volcanic eruptions, hazards and risks (IAVCEI News 2014 No. 2). Only time will tell whether we are seeing the emergence of an independent, self-regulating, professional association for volcanologists – an association with the will, mandate and ability to provide some form of ‘standard unequivocality’, in other words, standards of acceptable practice.

Praemonitus, praemunitus - Forewarned is forearmed

Each jurisdiction that hosts volcanic hazards will have its own legal regime and histories of jurisprudence and legal practice. A prudent volcanologist will take proactive steps to seek basic advice about their legal responsibilities and professional risks. A number of generalised working assumptions can be made which may prompt and guide cautious due diligence.

Under a number of ‘Getting better’ and ‘Getting smarter’ subheadings, we link the most significant characteristics of legal scrutiny processes to managerial risks, which may susceptible to mitigation, and we offer in respect of each a non-exhaustive set of recommendations for action.

Getting better - Addressing the challenge of standard equivocality

There is general legal principle that a professional, or someone purporting to act professionally, should act in accordance with: (1) the practice accepted as proper by a responsible, reasonable and respectable body of opinion; or (2) the recognised practice within his/her profession. Simoncini (2014) refers to the level of diligence which is expected from the so-called ‘model agent’ (homo eiusdem professionis et condicionis). She states that it consists of the hypothetical and ideal behaviour of an agent who, by availing himself of personal and common professional experience in that particular field, is developing his task in the best possible way and avoids predictable risk and avoidable consequences.

Opinion evidence will be usually be adduced: (1) to establish what should have happened before, during and after the index event in order to fulfil the functions and/or achieve the goals required by law; and (2) to avoid the foreseeable and difficult problem of ‘hindsight bias’ correctly identified by Gabrielli & Di Bucci (2014) and Lauta (2014a). At the moment the acceptable practices of volcanology, and in particular volcano observatories, are very difficult to access. They may only be identified too late – after a tragedy.

The thorny issue of ‘standard equivocality’ must be confronted. Further consideration should be given to the drafting of checklists to encourage the active and routine consideration of critical issues and priorities. Their purpose would be to identify, record, promote and develop accepted practice (Newhall 2010 Footnote 20). They might address a range of topical issues such as hazard communication, communicating uncertainty and disagreement and the use of scientific and geological jargon.

Checklists may encourage rational, systematic, routine and transparent due diligence whilst recognising the importance of, and encouraging careful attention to, a wide variety of constraints and expectations. These drivers include geological, geographical, technical, contractual, local, colonial, government structure,Footnote 21 historical, cultural,Footnote 22 spiritual, linguistic,Footnote 23 legal, time and resource related, and organisational Footnote 24 factors.Footnote 25 Constraints may also be imposed by legal or pragmatic needs to engage with and consult stakeholders in other jurisdictions who ‘share’ the hazards in question and/or their risks.

It is not envisaged that these checklists would be either: (1) a regulatory device or an enforceable legal requirement; or (2) ‘procedural armour against blame’, in other words a blame-avoidance strategy that encourages “sticking to the rules” and prioritises adherence to rules or protocols of process above the achievement of ‘results’ (i.e. services focused upon and relevant to the needs of risk decisions and their makers) (Hood 2001).Footnote 26