Abstract

Purpose

The present study aimed at assessing the prevalences of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (main objective), anxiety, depression, and burnout syndrome (BOS) and their associated factors in intensive care unit (ICU) staff workers in the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and methods

An international cross-sectional multicenter ICU-based online survey was carried out among the ICU staff workers in 20 ICUs across 3 continents. ICUs staff workers (both caregivers and non-caregivers) were invited to complete PCL-5, HADS, and MBI questionnaires for assessing PTSD, anxiety, depression, and the different components of BOS, respectively. A personal questionnaire was used to isolate independent associated factors with these disorders.

Results

PCL-5, HADS, and MBI questionnaires were completed by 585, 570, and 539 responders, respectively (525 completed all questionnaires). PTSD was diagnosed in 98/585 responders (16.8%). Changing familial environment, being a non-caregiver staff worker, having not being involved in a COVID-19 patient admission, having not been provided with COVID-19-related information were associated with PTSD. Anxiety was reported in 130/570 responders (22.8%). Working in a public hospital, being a woman, being financially impacted, being a non-clinical healthcare staff member, having no theoretical or practical training on individual preventive measures, and fear of managing COVID-19 patients were associated with anxiety. Depression was reported in 50/570 responders (8.8%). Comorbidity at risk of severe COVID-19, working in a public hospital, looking after a child, being a non-caregiver staff member, having no information, and a request for moving from the unit were associated with depression. Having received no information and no adequate training for COVID-19 patient management were associated with all 3 dimensions of BOS.

Conclusion

The present study confirmed that ICU staff workers, whether they treated COVID-19 patients or not, have a substantial prevalence of psychological disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In December 2019, the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 resulted in a worldwide outbreak of respiratory illness termed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with clinical presentation ranging from asymptomatic disease to severe progressive pneumonia with multiorgan failure. Over 6,537,636 worldwide patients have died (October 12, 2022) [1,2,3], and although overall mortality is around 3%, the mortality rate of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) ranges from 20% to more than 60% [1, 3,4,5,6,7]). With few substantially disease modifying antiviral SARS-CoV-2 therapeutic agents, the current therapeutic strategy is based largely on symptomatic treatment and the prevention of transmission [8].

The COVID-19 pandemic presented with different intensities between countries. Therefore, some countries tried to fight and/or delay the start of the pandemic to reduce the peak infection rates of the disease. These actions aimed at reducing the overall pressure on national healthcare systems and was intended to decrease the COVID-19 mortality rate [9, 10].

Based on the experience of previous pandemics, countries reacted by applying different transmission prevention strategies to prevent or delay the spread of the disease [9,10,11]. Therefore, measures such as border closure, school closure, restricting social gatherings (even shutdown of workplaces), limiting population movements, and lockdowns at the scale of cities or regions were put into action. In public hospitals, several measures were implemented to concentrate care resources on the potential wave of admissions of patients with severe forms of COVID-19. For this reason, the number of available beds in the ICU was frequently increased by up to two-fold [12, 13], and scheduled non-emergency surgical procedures were canceled. Frequently underutilized health care professionals (physicians such as anesthesiologists, and nurses of other units) were transferred to ICUs, and those of less busy units were transferred to busier ones.

All these measures lead to major daily-life changes that could be stressful to individuals. In the general population, it has been well documented that quarantine or confinement, or isolation may lead to the occurrence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in about 30% of the exposed population [14]. Importantly, high levels of depressive symptoms have been reported in up to 9% of hospital staff [15]. Numerous symptoms, such as emotional disturbance, depression, stress, low mood, irritability, insomnia, and post-traumatic stress symptoms have been reported after quarantine or isolation [14].

In the ICU setting, it has been shown that the COVID-19 pandemic led to psychological consequences on caregivers. During the second wave in France (autumn 2020), Azoulay et al. reported symptoms of anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and burnout in 60.0%, 36.1%, 28.4, and 45.1%, respectively, in 845 health care providers (66% nursing staff, 32% medical staff, 2% other professionals [16]). However, because the pandemic has continued over a prolonged period, with potentially different impacts on the population and healthcare systems, and varying in intensity according to the vaccination rate, the present study aimed at assessing the occurrence of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and burnout syndrome (BOS) in ICU staff workers in Australia (Queensland), France and Hong Kong after the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The primary objective was to assess the prevalence of PTSD in ICU staff workers. The secondary objectives were to identify potential associated factors to the occurrence of PTSD and to assess the prevalence of anxiety, depression, BOS, and their related associated factors in the same cohort.

Material and methods

Design

An international cross-sectional multicenter (20 centers) ICU-based online survey was carried out among ICU staff workers in Australia, France, and Hong Kong.

According to French law, this study does not involve patients and is considered a quality-of-care assessment [17]. Therefore, the Institutional Review Board of the Nîmes University Hospital (# 20.05.08) and of the French Society of Anesthesia and Critical Care (IRB 00010254-2020-148) gave their approvals. This study was registered on ClinicalTrial.gov (NCT04511780 first posted on August 13, 2020) before the inclusion of the first participant. In Australia and Hong Kong (SBRE (226-20)), the local ethics committees of each institution gave study approval.

Around the time of the survey administration, in Hong Kong and France there were significant numbers of COVID related admissions to the ICUs, whereas at Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital in Brisbane, Australia, COVID-19-related ICU admissions occurred post survey only.

The survey included 5 different questionnaires:

-

1)

The center demographic questionnaire that focused on the nature and organization of the ICU:

-

Type of hospital;

-

Number of beds in 2020;

-

Different categories of staff;

-

Number of COVID-19 patients admitted to the unit;

-

Alteration in ICU organization during the COVID-19 pandemic (increase in staff, additional beds, educational program for the staff, psychological support);

-

Numbers of death among COVID-19 patients.

-

-

2)

The individual demographic questionnaire that collected personal information:

-

Personal socio-demographic data and their changes during the pandemic;

-

Professional characteristics (job title, experience), their experience during the COVID-19 pandemic (feeling, family, and professional relationships);

-

-

3)

Validated questionnaires for assessing PTSD (PCL-5) [18]

-

4)

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) for assessing symptoms of anxiety and depression [19]

-

5)

Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS-MP) for assessing BOS [20, 21].

Study population

The principal investigators contacted ICUs in Australia, France and Hong Kong to participate. After center approval, all ICU staff workers (caregivers in contact with patients and non-caregivers) could participate in the present study. After having had the ability to read an information note about the study, responding to the questionnaire was considered to imply informed consent.

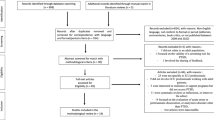

The inclusion criteria were caregiver and non-caregiver staff working in the ICU during the COVID-19 outbreak and consent to complete the questionnaire. The recruitment was performed between February 25th, 2021 and June 8th, 2022.

The non-inclusion criteria were participation refusal and non-response to the questionnaire. Partially completed questionnaires were excluded.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the prevalence of PTSD (defined by a PCL-5 score ≥ 32) and its 95% confident interval (95% CI).

The secondary outcomes were to identify potential associated factors with occurrence of PTSD and to the prevalences of anxiety and depression according to the HADS questionnaire, and burnout assessed by the MBI-HSS (MP) self-questionnaire.

Anxiety and depression were separately assessed by the HADS questionnaire according to the following rules:

-

0 to 7: absence of disorder;

-

8 to 10: suspected disorder;

-

11 to 21: proven disorder.

Burnout syndrome was assessed by the MBI-HSS (MP) in its 3 specific sub-scales allowing for the evaluation of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment dimensions, respectively. However, many controversies remain unsolved for the global MBI assessment: [20, 22]

-

1.

Personal accomplishment is not always taken into account in the global MBI score;

-

2.

In each subscale, the different thresholds are challenged.

Thus, we have analyzed the 3 sub-scores both separately and continuously.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective, i.e., to evaluate the prevalence of PTSD, was measured with the PCL-5 score and classified as probable PTSD versus no PTSD with PCL-5 scores of ≥ 32 versus < 32 with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), respectively. The prevalence of PTSD was estimated in the total sample and in each country.

The associated factors with PTSD were searched as secondary objectives. For this purpose, we selected variables with univariate logistic regression to reduce the dimensionality of the model (relaxed alpha = 0.2) and then applied a multivariate logistic regression with backward selection (alpha = 0.05). First, the univariate analysis compared the dichotomous/categorical/nominal variables (expressed as numbers and percentages) according to PTSD occurrence by the chi-square test or the Fisher exact test when necessary. The links between the explanatory variables and PTSD variables were expressed by the odds ratios and their 95% CI by the Wald method. Covariates with a p-value ≤ 0.20 in the univariate analysis were pre-selected to perform a multivariate analysis and a backward selection strategy at the 5% threshold was applied. Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) was provided with 95% CI. Importantly, the prevalence of PTSD was assessed in all completed PCL-5 (n = 585) whereas the associated factors were searched in participants who completed PCL-5 AND personal life questionnaires (n = 525).

For the other secondary objectives, the same analysis strategy was applied to evaluate the prevalence of anxiety, depression on one hand, and the factors associated with these disorders on the other (using the same method used for PTSD and associated factors). A polytomous logistic regression with a proportional-odds cumulative logit model was used to search for factors associated with anxiety and depression classified in a 3-level ordinal variable. The scores of the emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment subscales were expressed as mean, standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR). The associated factors to the 3 sub-scores were assessed with a multiple linear regression model. The same variable selection strategy was used for the previous models. Pearson correlation coefficients between PTSD, anxiety, depression, emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment scores are provided with their 95% CI. All statistical analyses used SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

The flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. Among 701 responders (in 20 different centers), 585, 570, and 539 completed PCL-5, HADS, and MBI questionnaires, respectively. All questionnaires were completed by 525 responders (511 caregivers and 14 non-caregivers).

PTSD prevalence

A PCL-5 score ≥ 32 was reported in 98 out of 585 responders (prevalence = 16.8%, 95% CI [13.7–19.8%]) with significant difference between countries: France (prevalence = 74/448, 16.5% 95% CI [13.1–20.0%]), Australia (prevalence = 16/111, 14.4% 95% CI [7.9–21.0%]) and Hong Kong (prevalence = 8/26, 30.8% 95% CI [13.0–48.5%].

According to the multivariate analysis (including 525 participants who fully completed PCL-5 and personal life questionnaires), 5 factors were associated with greater frequency of PTSD (Table 1): changing in the home environment during the COVID-19 pandemic, being a non-caregiver, having no COVID-19 patient admission, and no information on the evolution of the pandemic.

PCL-5 score was highly correlated with anxiety (r = 0.73, 95% CI [0.69–0.77], p < 0.0001), depression (r = 0.73, 95% CI [0.69–0.77], p < 0.0001) and emotional exhaustion (r = 0.70, 95% CI [0.62–0.71], p < 0.0001) scores (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Anxiety

A positive anxiety disorder (HADS score between 11 and 21) was reported in 130 out of 570 responders (prevalence = 22.8%, 95% CI [19.4–26.3%]) with no difference between countries: France (prevalence = 98/438, 22.4% 95% CI [18.5–26.3%]), Australia (prevalence = 26/108, 24.1% 95% CI [16.0–32.1%]) and Hong Kong (prevalence = 6/24, 25.0% 95% CI [7.7–42.3%]).

According to the multivariate analysis (including 525 participants who fully completed HADS and personal life questionnaires), working in a public hospital, being a woman, being financially impacted during the pandemic, being a non-caregiver, having no theoretical or practical training on individual preventive measures, and fear of managing COVID-19 patients were associated with a greater frequency of proven anxiety disorder (Table 2).

Depression

A positive depressive disorder (HADS score between 11 and 21) was reported in 50 out of 570 responders (prevalence = 8.8%, 95% CI [6.5–11.1%]) with significant difference between countries: France (prevalence = 40/438, 9.1% 95% CI [6.4–11.8%]), Australia (prevalence = 9/108, 8.3% 95% CI [3.1–13.6%]) and Hong Kong (prevalence = 1/24, 4.2% 95% CI [0.0–12.2%]).

According to the multivariate analysis (including 525 participants who fully completed HADS and personal life questionnaires), comorbidity at risk of severe COVID-19, working in a public hospital, looking after a child, being a non-caregiver, having no information on the evolution of the pandemic, having requested a change of unit for not working in a COVID unit were associated with a greater occurrence of proven depressive disorder (Table 2).

Sub-scores of burnout

Emotional exhaustion

The emotional exhaustion score in the total sample was 23.5 ± 13.7.

According to the multivariate analysis (including 525 participants who fully completed MBI and personal life questionnaires), usually living alone, being a non-caregiver, having no information on the evolution of the pandemic, not being adequately trained to manage a COVID-19 patient, not having accepted managing COVID-19 patients, and fear of managing a COVID-19 patient were independently associated with greater emotional exhaustion (Table 3).

Depersonalization

The depersonalization score in the total sample was 9.1 ± 7.0.

According to the multivariate analysis, having been infected with SARS-CoV-2 and having no information on the evolution of the pandemic were associated with a higher depersonalization score. An age > 50 years was associated with lower depersonalization (Table 3).

Personal accomplishment

The loss of personal accomplishment score in the total sample was 35.3 ± 7.9.

According to the multivariate analysis, comorbidity at risk of severe COVID-19, working in a public hospital, having no theoretical or practical training on individual preventive measures, and insufficient information about the management of COVID-19 patients were associated with lower personal accomplishment (Table 3).

Emotional exhaustion and Depersonalization scores were both correlated (r = 0.57, 95% CI [0.51–0.63], p < 0.0001), whereas the latter were negatively but less correlated with personal accomplishment (Additional file 1: Table S1). The position and dispersion parameters associated with each score are reported in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Discussion

In the present study performed in 20 centers in Australia, France, and Hong Kong, 525 ICU staff workers responded to the PCL-5, HADS, and MBI questionnaires. PTSD was present in 16.8% of participants with the highest prevalence in Hong Kong (30.8%). Anxiety and depressive disorders were reported in 22.8 and 8.8% of responders, respectively. The common associated factors with PTSD, anxiety, and depression were being a non-caregiver worker and not having been regularly informed of the COVID-19 progression during the pandemic. Concerning BOS, not having been regularly informed of the COVID-19 progression was associated with higher scores for emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and the loss of personal accomplishment, respectively.

The present study was performed during the second year of the COVID-19 pandemic in 3 different countries with different impacts of this pandemic, different strategies to prevent contamination, and different population vaccination rates. These factors could explain the different prevalences of PTSD, anxiety, and depression reported in previous studies that were essentially performed in European countries during the first and second waves. The FAMIREA group performed two studies in the first and second waves in 21 and 16 centers involving 845 (70% responders) and 1058 (67% responders healthcare professionals, respectively [16, 23]. The prevalences of PTSD were successively 32.0 and 28.4% with anxiety and depression reported in 50.4 to 60.0% and 30.4 to 36.1%, during the first and second waves, respectively. During the second wave, the authors reported a burnout syndrome in 45.1% using an overall score [23].

In January 2021, a single center study involving 136 healthcare workers (84 nurses, 52 physicians) in a temporary ICU during the pandemic in Milano Fiera, Lombardy reported 60% burnout syndrome, 53% anxiety (especially in nurses), and 45% depression [24]. In June–July 2020, a cross-sectional study involving 709 healthcare providers from 9 English ICUs reported 40% PTSD, 11% severe anxiety, and 6% severe depression. In May 2020, a cross-sectional study involving 352 Swiss ICU healthcare workers reported 22% PTSD, 46% anxiety, and 46% depression [25].

The present study reports lower prevalences of PTSD, anxiety, and depression than the previous ones performed in the first two waves of the pandemic. Our findings could mean that the impact of COVID-19 pandemic has been blunted overtime. Indeed, the present findings are close to those observed at baseline prior to the COVID-19 pandemic [16, 23, 26]. Another explanation could be related to different cultures, different impact of the pandemic and policies on restriction, lockdown, and vaccine strategies in Hong Kong Australia, and France [27,28,29].

The present study also reported that ICU staff workers in contact with COVID-19 patients are at lower risk of psychological consequences than those not in charge of these patients. This paradoxical phenomenon has been regularly reported in previous studies [14]. Indeed, being far from the patients with no information and education about the disease could lead to fear, anxiety, stress, and other psychological consequences. The absence of information about local progression of the pandemic was also associated with BOS in its 3 dimensions (emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and loss of personal accomplishment).

In contrast to the previous studies, a quantitative approach to BOS was performed. A threshold of MBI is classically used for diagnosing BOS. However, this dichotomous analysis has been challenged because MBI aggregate 3 different and independent part of the diagnosis. In 2016,

the cut-off scores were removed by the MBI Manual 4th edition because they have no diagnostic validity [30]. Even with this difference, the present study reported similar associated factors with the 3 different parts of BOS (lack of information about local progression of the pandemic and lack of theoretical or practical training on COVID-19 patient management). The present study highlighted several factors associated with PTSD, anxiety, depression, and symptoms of BOS. Moreover, it involved ICUs from different continents. Hong Kong was firstly impacted by the pandemic. France was also severely impacted by the first two waves with some ICU overwhelming episodes. Australia and particularly Queensland closed their borders and had limited transmission and cases in the early stages. Finally, the courses of vaccination covert were different according to the general health strategy against the COVID-19 pandemic. These differences could partly explain the heterogeneous findings of the present study.

We must acknowledge some limitations. First, the participation rate was only 16%, which is consistent with cross-sectional surveys. We did not send personal reminders to respect responder anonymity. Another reason may be the timing of our study (after the third wave, February–July 2021) that was perhaps too far from the start of the pandemic with participant weariness leading to a low response rate. The present study, therefore, likely reported the chronic states of stress, anxiety, depression, and BOS in ICU staff. Second, the cross-sectional survey design only led to isolating associated factors with PTSD, anxiety, depression, and BOS. For isolating risk factors of these psychological disorders, cohort or case–control designs might have been more appropriate. Third, the sample of the present study was not well balanced with a preponderance of French participation. Fourth, non-care giving staff was also underrepresented in this study. Finally, it is well known that the demands of working in ICUs could lead to psychological disorders such as PTSD, anxiety, depression and BOS. As no baseline assessment of these disorders was conducted before the pandemic, we cannot rule out the fact the present study reported only the baseline psychological state [26].

Conclusion

Our findings confirmed that ICU staff workers continue to suffer from psychological disorders. Even if some factors are linked to the COVID-19 pandemic (fear of managing COVID-19 patients), the lack of theoretical and practical training in the management of COVID-19 patients as well as the lack of information on the current status of the pandemic within the ICU were associated with a higher prevalence of PTSD, anxiety, depression, and BOS. These findings suggest the importance of good communication amongst staff in the ICU for staff wellbeing.

Availability of data and materials

Nimes University Hospital, BESPIM Department.

References

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–13.

Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, Zhu F, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061.

Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, Shu H, Xia J, Liu H, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81.

Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, Lokhandwala S, Riedo FX, Chong M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1612.

Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, Liu W, Wang J, Fan G, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787–99.

Roger C, Collange O, Mezzarobba M, Abou-Arab O, Teule L, Garnier M, et al. French multicentre observational study on SARS-CoV-2 infections intensive care initial management: the FRENCH CORONA study. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2021;40(4): 100931.

Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):854–87.

Markel H, Lipman HB, Navarro JA, Sloan A, Michalsen JR, Stern AM, et al. Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by us cities during the 1918–1919 influenza pandemic. JAMA. 2007;298(6):644.

World Health Organization Writing Group. Nonpharmaceutical Interventions for Pandemic Influenza. Int Meas Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(1):81–7.

Haber MJ, Shay DK, Davis XM, Patel R, Jin X, Weintraub E, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to reduce contact rates during a simulated influenza pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(4):581–9.

Lyons RA, Wareham K, Hutchings HA, Major E, Ferguson B. Population requirement for adult critical-care beds: a prospective quantitative and qualitative study. Lancet. 2000;355(9204):595–8.

Conway R, O’Riordan D, Silke B. Targets and the emergency medical system—intended and unintended consequences. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015;22(4):235–40.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15–23.

Azoulay E, Pochard F, Reignier J, Argaud L, Bruneel F, Courbon P, et al. Symptoms of mental health disorders in critical care physicians facing the second COVID-19 wave: a cross-sectional study. Chest. 2021;160:944–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.05.023.

Toulouse E, Granier S, Nicolas-Robin A, Bahans C, Milman A, Andrieu VR, Gricourt Y. The French clinical research in the European Community regulation era. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2023;42: 101192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2022.101192. (Epub 2022 Dec 23).

Ashbaugh AR, Houle-Johnson S, Herbert C, El-Hage W, Brunet A. Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10): e0161645.

Spinhoven Ph, Ormel J, Sloekers PPA, Kempen GIJM, Speckens AEM, Hemert AMV. A validation study of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychol Med. 1997;27(2):363–70.

Lin CY, Alimoradi Z, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH. Psychometric properties of the Maslach Burnout Inventory for Medical Personnel (MBI-HSS-MP). Heliyon. 2022;8(2): e08868.

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organiz Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113.

Lheureux F, Truchot D, Borteyrou X, Rascle N. The Maslach Burnout Inventory—Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS): factor structure, wording effect and psychometric qualities of known problematic items. Le Travail Humain. 2017;80(2):161–86.

Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, Demoule A, Kouatchet A, Reuter D, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19. a cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):1388–98.

Stocchetti N, Segre G, Zanier ER, Zanetti M, Campi R, Scarpellini F, et al. Burnout in intensive care unit workers during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: a single center cross-sectional Italian study. IJERPH. 2021;18(11):6102.

Wozniak H, Benzakour L, Moullec G, Buetti N, Nguyen A, Corbaz S, et al. Mental health outcomes of ICU and non-ICU healthcare workers during the COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional study. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):106.

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Perrin M, Soufir L, Vesin A, Blot F, Maxime V, et al. The Iatroref study: medical errors are associated with symptoms of depression in ICU staff but not burnout or safety culture. Intensive Care Med févr. 2015;41(2):273–84.

Bardosh K, de Figueiredo A, Gur-Arie R, Jamrozik E, Doidge J, Lemmens T, et al. The unintended consequences of COVID-19 vaccine policy: why mandates, passports and restrictions may cause more harm than good. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7(5): e008684.

Chan HY, Chen A, Ma W, Sze NN, Liu X. COVID-19, community response, public policy, and travel patterns: a tale of Hong Kong. Transp Policy. 2021;106:173–84.

Attwell K, Rizzi M, McKenzie L, Carlson SJ, Roberts L, Tomkinson S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine mandates: an Australian attitudinal study. Vaccine. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.056.

mindgarden. The problem with cut-offs for the Maslach burnout inventory. 2018. https://www.mindgarden.com/documents/MBI-Cutoff-Caveat.pdf. Accessed 17 Oct 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all colleagues and person who helped to collect and analyze the data: Pr Yazine Mahjoub (Amiens), Dr Julien Picard (Grenoble), Dr Olivier Vincent (Grenoble), M Albert Prades (Montpellier). The authors thank all participants for having answered the questionnaire.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design of the study: CR, LL, GMJ, JL, KL, IC, KL, JYL. Questionnaire validation: CR, LL, JL, KL, IC, KL, JYL, MP, PFP. Site local organization: CR, LL, GMJ, MP, LE, EA, BA, FA, JMC, CDF, ND, HD, MOF, MG, EG, CI, SJ, JM, BP, TR, SR, RS, GMJ, JYL, PFP, JL, IC, KL JL, KL, IC, KL, JYL. Data management and statistical analysis: MP, PFP, LE, CR, JYL. Writing the article: CR, LL, MP, GMJ, JYL, PFP, JL, IC, KL. Final approval of the article: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In France, the Institutional Review Board of the Nîmes University Hospital (# 20.05.08) and the Institutional Review Board of the French Society of Anesthesia and Critical Care (IRB 00010254–2020–148) approved the study. In Australia and Hong Kong (SBRE (226–20)), the local ethics committees of each institution gave study approval. After having had the ability to read an information note about the study, responding to the questionnaire was considered to imply informed consent.

Consent for publication

All authors approved the final version and consent to publish.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests. The authors disclose the use of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Table S1. Pearson correlation coefficients (between all scales). Table S2. Dispersion and position parameters associated with the assessment scales for psychological disorders.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Roger, C., Ling, L., Petrier, M. et al. Occurrences of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and burnout syndrome in ICU staff workers after two-year of the COVID-19 pandemic: the international PSY-CO in ICU study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 23, 3 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00488-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-023-00488-5