Abstract

Somatic mutations of KIT are frequently found in mastocytosis and gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), while germline mutations of KIT are rare, and only found in few cases of familial GIST and mastocytosis. Although ligand-independent activation is the common feature of KIT mutations, the phenotypes mediated by various germline KIT mutations are different. Germline KIT mutations affect different tissues such as interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), mast cells or melanocytes, and thereby lead to GIST, mastocytosis, or abnormal pigmentation. In this review, we summarize germline KIT mutations in familial mastocytosis and GIST and discuss the possible cellular context dependent transforming activity of KIT mutations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Great progress has been made in the targeted therapy of cancer in recent years. Numerous targeted therapies have been approved for the treatment of various cancers. The number of new drugs targeting specific proteins or pathways is increasing rapidly. In many cancers, protein kinases are deregulated, and therefore, are the most often used therapeutic targets in the treatment of cancer. Gain-of-function mutations, overexpression, genomic rearrangements and autocrine activation of kinases are the frequent causes of cell transformation in most malignancies [1–3].

KIT is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is implicated in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), mastocytosis and core binding factor (CBF) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [4]. Imatinib is a small molecule inhibitor that was originally developed to inhibit BCR-ABL fusion protein which later found to inhibit the activity of KIT [5]. Thus, imatinib was approved for the treatment of GIST [6], where it improved the treatment outcome dramatically. Due to the resistance of some primary or secondary KIT mutations to Imatinib, new inhibitors of KIT were developed. Recently, Sunitinib and Regorafenib were approved as second and third line treatment of GIST respectively [7, 8].

Mutations of KIT are the dominant genetic lesion in GIST and mastocytosis. Both somatic and germline mutations of KIT have been described in GIST, mastocytosis and other cancers [9–12]. Mutations of KIT were found in almost each domain of KIT while the distribution of the mutations is not random. There are some hotspots of somatic mutations of KIT and the hotspots in GIST and mastocytosis are different with the reason unknown.

KIT is important for the development of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC), mast cells and melanocytes [13, 14]. However, germline mutations of KIT do not necessarily induce the transformation or overgrowth of all three types of cells and show different phenotypes in the patients, which might reflect the tissue-specific transforming ability of KIT mutations and explain the difference in the hotspots of somatic KIT mutations in different malignancies. These mutations could be good models to study tissue-specific transforming mechanism of KIT mutations and contribute to design effective targeted therapy of malignancies carrying KIT mutations. In this review, we summarize germline KIT mutations in familial mastocytosis and GIST and discuss how different KIT mutations induce cell transformation in different tissues.

Signal transduction of wild-type KIT

KIT was cloned in 1987 as the human homolog of its viral counterpart, v-kit. The KIT gene is localized to the human chromosome 4 and on mouse chromosome 5 [15]. KIT is a member of type III receptor tyrosine kinase together with FLT3, PDGFR and CSF-1R. This family of kinases is characterized by an extracellular ligand-binding domain consisting of five immunoglobulin-like regions, a transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane domain and an intracellular kinase domain which is separated by a short kinase insert. KIT plays important roles in melanogenesis, gametogenesis, and hematopoiesis [4]. The ligand for KIT, stem cell factor (SCF), is encoded by sl locus of the mouse and it was cloned in 1990 [16, 17].

Stimulation of KIT with its ligand, SCF, leads to the dimerization of receptors and activation of the intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity followed by phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues in the intracellular domain. In KIT, several tyrosine residues including Tyr 568, Tyr 570, Tyr 703, Tyr 721, Tyr 730, Tyr 823, Tyr 900, Tyr 936 can be phosphorylated upon SCF stimulation [18–23]. Phosphorylated tyrosines, together with adjacent amino acid residues, form specific binding sites for downstream signaling molecules and activate specific downstream signaling pathways.

Phosphorylation of Tyr 568 plays a critical role in the activation of KIT and downstream signaling pathways. Phosphorylated Tyr 568 can activate Src family kinases [18, 24] and the Src family kinases in turn further enhance the activation of KIT [25]. Inhibition of Src family kinases leads to attenuation of KIT activation, indicating that the activity of Src family kinases is necessary for the complete activation of KIT. In addition, Src family kinases can activate SHC and Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk signaling cascade that is important for KIT-mediated cell proliferation [18].

Another important KIT phosphorylation site is Tyr 721, which acts as the docking site for the regulatory subunit p85 of the PI3 kinase [20]. Activation of PI3 kinase and its downstream signaling pathways regulates the KIT-mediated cell survival and proliferation [26]. The Tyr 721 is not the only site involved in PI3 kinase activation by KIT. It has been demonstrated that Tyr 703 and Tyr 936 are the binding sites for the adaptor protein Grb2, which in turn recruit PI3 kinase through Gab2 and activates downstream signaling cascades. Gab2 is also involved in activation of Ras-Raf-Mek-Erk signaling cascade [27].

Activation of KIT is tightly controlled to avoid excessive activation of downstream signaling pathways. One mechanism of negative regulation of KIT activity is Cbl-mediated ubiquitination. Cbl is an E3 ubiquitin ligase which associates with the phospho-Tyr 568 and Tyr 936 residues in KIT [28] and induces the receptor degradation and thereby attenuates the signal transduction of the receptor. In addition, Grb2 is also involved in the recruitment of Cbl to the receptor [29]. Loss of Cbl function might prolong activation of KIT and its downstream signaling pathways.

Phosphorylation of other KIT tyrosine residues activates specific downstream signaling pathways and contributes to KIT-mediated cell response as well. Tyr 570 enhances the binding of Src family kinases to KIT although Tyr 570 does not bind to Src family kinases directly. Tyr 730 and Tyr 900 are docking sites for PLC-gamma and Crk respectively [22, 23] that can further activate their downstream signaling pathways. The tyrosine phosphorylation of wild-type KIT and activation of downstream signaling pathways are summarized in Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of the tyrosine phosphorylation sites in wild-type c-Kit and their interaction molecules. KIT is a transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase with an extracellular ligand-binding domain consisting of five immunoglobulin-like regions, a transmembrane domain, a juxtamembrane domain and an intracellular kinase domain which is separated by a short kinase insert. Upon binding of its ligand stem cell factor, some tyrosine sites as indicated in the intracellular domain of KIT are phosphorylated, leading to the activation of downstream signaling pathways

Signal transduction of KIT mutants

Somatic and germline mutations of KIT have been found in various malignancies which are mainly characterized by ligand-independent activation. Ligand-independent constitutive activation is considered as a cause of cell transformation induced by KIT mutants. However, recent studies suggest that KIT mutants gain extra activity in addition to the constitutive activation [30], and the activation mechanism, as well as downstream signaling pathways, are different compared to that of wild-type KIT [31–34].

The D816V mutation is the most often occurred and widely studied oncogenic KIT mutation. In addition to the ligand-independent activation, this mutation gains extra activity and it has different signaling pathways from that of wild-type KIT. For example, while the wild-type KIT activation and downstream signaling are partially dependent on Src family kinases, KIT/D816V gains Src-like kinase activity and it circumvents a requirement of Src family kinases in its signaling [30]. Similar to KIT/D816V, the exon 11 mutation V560D of KIT can be fully activated without Src family kinases although it does not have Src-like kinase activity [34]. These studies strongly suggest that oncogenic KIT mutations gain extra activity that wild-type receptor does not hold. These mutations can not only induce ligand-independent activation of the receptor but also might have different downstream signaling pathways compared with wild-type KIT. Elucidation of the activation mechanism and downstream signaling pathways of KIT mutants will contribute to drug design and targeted therapy of malignancies carrying KIT mutants.

PI3 kinase is an important downstream signaling molecule of KIT. It plays an important role in wild-type KIT-mediated cell proliferation [26], migration [35], and KIT/D816V mediated cell transformation [36]. Further study of PI3 kinase in the signal transduction of KIT mutants indicates that PI3 kinase not only activates Akt and related downstream signaling pathways, but also it plays a central role in the ligand-independent activation of KIT mutants. Blockage of the direct binding of PI3 kinase to KIT dramatically inhibits the ligand-independent activation of KIT/D816V and abolishes the transforming ability of KIT/D816V [32]. More strikingly, blockage of the direct binding of PI3 kinase to KIT completely blocks the ligand-independent activation of KIT/V560D [34], which further strengthens the key role of PI3 kinase in the ligand-independent activation of KIT mutants. Furthermore, the activity of PI3 kinase in the ligand-independent activation of KIT mutants does not rely on the lipid kinase activity of PI3 kinase [32, 34]. These data indicate that PI3 kinase can be an alternative drug target in malignancies induced by KIT mutants.

In addition to the different roles of Src family kinases and PI3 kinases in the activation of wild-type KIT and KIT mutants, the unique downstream signaling pathways of KIT mutants were studied. It has been shown that KIT/D816V, but not wild-type KIT, can induce tyrosine phosphorylation of p110delta and SLAP, and the phosphorylation of the two molecules contribute to KIT/D816V mediated cell transformation [32, 33]. The knowledge about the activation and signal transduction of KIT mutants is still very limited so far; more studies are needed to further understand the difference in the activation and downstream signaling pathways between wild-type KIT and KIT mutants.

Somatic mutations of KIT

Mastocytosis is characterized by abnormal proliferation and accumulation of mast cells in tissues. It is divided into systemic mastocytosis and cutaneous mastocytosis according to the infiltrated tissues. Mutations of KIT account for around 80 % of mastocytosis [37–39], and can be found in almost each region of KIT but are not randomly distributed. Exon 17 mutation, D816V of KIT is the most often occurred KIT mutation in mastocytosis [37]. In addition to D816V mutation, less common oncogenic mutations including D816F, D816H, D816Y, D820G in exon 17 [40–43], exon 10 and exon 11 mutations, F522C and V559I respectively are also identified in mastocytosis [44, 45]. In CBF AML, within many KIT mutations, D816V is the dominant mutation [46].

GIST is considered originate from ICC in the digestive tract. The average diagnostic age is the mid 60s [47]. KIT mutations are also the most common mutations in GIST similar as that in mastocytosis. Unlike mastocytosis in which exon 17 mutation D816V is the dominant KIT mutation, exon 11 mutation in KIT is most common in GIST, and exon 9 and 13 mutations are also often seen in GIST but to a less extent [48, 49]. Exon 17 mutation of KIT is mainly found as a secondary mutation in drug-resistant GIST after the failure of targeted therapy [50–52].

The reason for the difference in hotspots of KIT mutations between mastocytosis and GIST remains unknown, the study of KIT mutations in different host cells might give some clues. In a previous study, it was shown that the V560D mutation of KIT cannot support the survival of hematopoietic cells in the absence of the ligand, while expression of KIT/D816V in the same cell line is enough to support the cell survival in the absence of the ligand [34]. It is worth to mention that the V560D mutation is common in GIST and the D816V mutation happens frequently in mastocytosis, a hematological malignancy [32, 34]. It is possible that hematopoietic cells are not the right host cells for the transforming activity of KIT/V560D. In contrast to its high transforming activity in hematopoietic cells, expression of KIT/D816V in fibroblast cells display weak oncogenic potential [53] and so far no D816V mutation has been reported in GIST. Therefore, it is most likely that oncogenic potential of different KIT mutants profoundly dependent on host cell type or cancer type.

Germline mutations of KIT

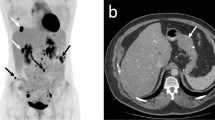

In contrast to somatic mutations, germline mutations of KIT were only found in few cases of familial mastocytosis and GIST, suggesting the transforming activity of germline mutations of KIT is limited to mast cells and ICC. So far, only 37 reports described 21 well-sequenced germline mutations in KIT (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Germline mutations of KIT in mastocytosis

Seven different germline KIT mutations in familial mastocytosis have been reported so far. In contrast to somatic KIT mutations in mastocytosis that were mainly found in exon 17, germline KIT mutations are located in exon 8, 9, 10, 13 and 17.

KIT is expressed in hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells and it plays important roles in the regulation of hematopoiesis. Differentiated hematopoietic cells lose expression of KIT with the exception of mast cells [89]. Interestingly, mast cells are the only hematopoietic cells that can be transformed by germline mutations of KIT. There are no any reports about deficiency in other hematopoietic cells in patients that carry germline mutations of KIT (Table 1), indicating that the transforming ability of germline mutations of KIT in hematopoietic system is limited to mast cells but not all KIT-expressing hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells. Sporadic mastocytosis associated leukemia has been reported [90], which indicate that somatic D816V mutation of KIT can transform other hematopoietic cells in addition to mast cells. Compared with D816V mutation, the germline mutations of KIT in familial mastocytosis are weak mutations in the hematopoietic system.

Gene mutations in sporadic mastocytosis are well studied, and KIT mutations are the major mutations of mastocytosis [91], however, the downstream signaling pathways of KIT mutants mediating transformation of mast cells remains unknown. Identification of the key signaling pathway in the transformation of mast cells will provide us novel drug targets and will contribute in developing of targeted therapy of mastocytosis. As we can see in Table 1, some germline KIT mutations, such as S451C, A533D, M541L, R634W and N822I, can induce only mastocytosis but not any other symptom that is related with a KIT mutation such as GIST, suggesting that these mutations can activate the necessary signaling pathways for mast-cell transformation. Study of these germline KIT mutation might elucidate the necessary signaling pathway that KIT mutations transform mast cells.

Germline mutations of KIT in GIST

The gastrointestinal tract is the most affected tissue in patients carrying germline KIT mutation, as indicated in Table 1, totally 15 different germline KIT mutations have been reported in GIST. Similar to somatic mutations of KIT in GIST, germline KIT mutations in exon 11 are the most common [49]. Germline KIT mutations of Val 559 and Lys 642 are hotspots in familial GIST (Fig. 2). Both mutations were also found as somatic mutations in sporadic GIST [92, 93].

Compared with mastocytosis, targeted therapy was well developed against KIT mutations in GIST. Imatinib, Sunitinib and Regorafenib are used as first, second and third line treatment of GIST, they have dramatically improved the treatment outcome [94]. However, some primary mutations and secondary mutations of KIT are resistant to the three approved KIT inhibitors; it is necessary to further study the activation mechanism and downstream signaling pathways of KIT mutants in GIST in order to improve the treatment. Some germline mutations of KIT, such as Y553C, W557R, D579del and K642E, only induce GIST but not mastocytosis (Table 1), the study of these KIT mutants might elucidate the specific transformation mechanism of KIT mutations in ICC.

Germline mutations of KIT in melanocyte

Melanocytes are another type of cells that are dependent on KIT for their lineage commitment, migration, and survival [95, 96]. Mutations in KIT or its ligand SCF lead to a defect in pigmentation [97]. Although BRAF mutation is the dominant mutation in melanoma, mutations in KIT gene have also been reported [98].

Only one germline mutation of KIT, V559A, has been described in melanoma so far [66], other patients in the same family carrying the same germline mutation of KIT did not develop melanoma. It is difficult to conclude that germline KIT mutation can induce melanoma based on the only observation. However, hyperpigmentation was reported in 10 cases of familial mastocytosis or GIST, suggesting that germline mutations of KIT can at least enhance the pigmentation (Table 1).

The same germline mutation of KIT induces different diseases

Germline mutations of KIT induce either GIST or mastocytosis except that D419del can induce both [54], suggesting that these mutations might have different activation mechanism and downstream signaling pathways and that their transforming ability might be cell type dependent or cellular context dependent.

Asn 822 in exon 17 can only induce GIST but not mastocytosis when it is mutated to Tyr [87] as germline mutation, while it can only induce mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) but not GIST when it is mutated into Ile [88]. It is interesting that one amino acid residue mutated into different amino acids leads to different phenotypes in the patients, which indicates possible different activation and/or downstream signaling pathways of the two different mutations in one site.

It is worth to note that some patients carrying the same germline KIT mutation, such as V559A, have different phenotypes. All family members carrying germline V559A mutation developed GIST and hyperpigmentation, meaning that V559A mutation of KIT is an oncogenic mutation in GIST and it can enhance pigmentation. Besides GIST, some patients also developed other symptoms such as urticaria pigmentosa [64, 66], and one patient even developed malignant melanoma and angioleiomyoma [66]. But these symptoms are not common among all the patients, meaning that V559A mutation of KIT cannot induce these symptoms by itself. It is possible that the mutation makes the patients sensitive to KIT mutation related other symptoms and additional factors are needed to cooperate with V559A mutation of KIT in the onset of other symptoms.

Same as V559A mutation, all patients carrying germline K642E mutation of KIT developed GIST, but they have opposite phenotypes concerning pigmentation. Some patients have nevi and lentigine [80], some patients have no abnormal pigmentation [81, 82] and other patients have paradoxical cutaneous depigmentation [83]. These different phenotypes in pigmentation suggest that K642E mutation of KIT might enhance, inhibit or have no effect on melanocyte depends on the situation. Maybe the same as V559A mutation, the phenotype might depend on other factors as well. It is interesting to identify the factor that can decide the outcome of the mutation in pigmentation. Identification of these factors will give clues about the oncogenesis of melanoma, and contribute to the treatment of melanoma.

Both V559A and K642E mutations of KIT were also identified as somatic mutations in melanoma [99, 100]. Since the patients that carry germline V559A and K642E mutations of KIT do not necessarily develop melanoma although some of them have hyperpigmentation, it can be concluded that these two mutations are not driver mutations in melanoma.

Germline K509I mutation of KIT was reported in few cases of familial mastocytosis. The patients carrying germline KIT/K509I have normal pigmentation, suggesting that the mutation probably behave similarly as wild-type KIT in melanocytes and it has on transforming activity in melanocytes. GIST is only reported in one patient but not all patients are carrying germline K509I mutation of KIT, meaning that K509I mutation of KIT is not an oncogenic mutation in GIST.

Knockin mice carrying germline mutations of KIT

Mice are widely used animal models in life sciences. Mutations of KIT were introduced into the murine genome to study their transforming potentials. Germline D818Y mutation of murine KIT (identical to D820Y of human KIT) was made in mice. Mice carrying both homozygous and heterozygous D818Y mutation of KIT developed GIST [101], they recapitulated the phenotype showed by patients carrying germline D820Y mutation of KIT. No disorder in mast cells and pigmentation was reported in the knockin mice; that is in line with the phenotype of the patients carrying germline D820Y mutation of human KIT.

Deletion of V558 in KIT was also generated in murine genome. Mice carrying heterozygous V558del mutation of KIT developed GIST [102]. In addition, these mice also had increased the amount of mast cells in tissues although they did not develop mastocytosis. Which means that this mutation can enhance the proliferation of mast cells although it cannot transform mast cells, the transforming activity of V558del mutation of KIT is limited in ICC.

Similar as above two mutations, knockin mice harboring a K641E mutation of KIT (identical to K642E mutation of human KIT) also developed GIST [103], indicating that K642E mutation of KIT is a driver mutation in GIST. Interestingly, mice carrying a homozygous K642E mutation of KIT showed loss-of-function phenotypes in pigmentation, hematopoiesis and gametogenesis. These mice had white fur, very few mast cells and they were infertile. The loss-of-function phenotypes strongly suggest that K624E mutation of KIT is a loss-of-function mutation in melanocytes, hematopoietic cells and germ cells. It is interesting that one mutation can act as both gain-of-function mutation and loss-of-function mutation. The mechanism behind that might reflect the tissue-specific activation mechanism of KIT mutations and further explain the difference in hotspots of KIT mutations between GIST and mastocytosis. The germline mutations of KIT carried by the patients is usually heterozygous, maybe one copy of wild-type KIT is enough to support normal pigmentation, hematopoiesis and gametogenesis as showed by mice carrying a heterozygous K641E mutation of KIT. From the different phenotypes showed by knockin mice carrying heterozygous and homozygous K641E mutation of KIT, we can know that patients carrying germline mutations of KIT cannot always precisely reflect the function of KIT mutations since the mutations carried by these patients are usually heterozygous. Homozygous knockin mice are sometimes necessary to confirm the role of KIT mutations.

Conclusions

The different phenotypes mediated by various germline mutations of KIT might reflect the cellular context dependent transforming ability of kit mutations and explain the difference in hotspots of KIT mutations between GIST and mastocytosis. Germline mutations of KIT can give the information about the necessary signaling pathways in the transformation of a certain type of cells. Study on the activation and downstream signaling pathways of germline KIT mutations will elucidate the tissue-specific transformation mechanism of KIT mutations, and which will further contribute to the developing of targeted therapy of malignancies that carry KIT mutations.

References

Blume-Jensen P, Hunter T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature. 2001;411:355–65.

Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–34.

Torkamani A, Verkhivker G, Schork NJ. Cancer driver mutations in protein kinase genes. Cancer Lett. 2009;281:117–27.

Lennartsson J, Ronnstrand L. Stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit: from basic science to clinical implications. Physiol Rev. 2012;92:1619–49.

Iqbal N, Iqbal N. Imatinib: a breakthrough of targeted therapy in cancer. Chemother Res Pract. 2014;2014:357027.

Dagher R, Cohen M, Williams G, Rothmann M, Gobburu J, Robbie G, Rahman A, Chen G, Staten A, Griebel D, Pazdur R. Approval summary: imatinib mesylate in the treatment of metastatic and/or unresectable malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3034–8.

Goodman VL, Rock EP, Dagher R, Ramchandani RP, Abraham S, Gobburu JV, Booth BP, Verbois SL, Morse DE, Liang CY, Chidambaram N, Jiang JX, Tang S, Mahjoob K, Justice R, Pazdur R. Approval summary: sunitinib for the treatment of imatinib refractory or intolerant gastrointestinal stromal tumors and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1367–73.

Sirohi B, Philip DS, Shrikhande SV. Regorafenib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Future Oncol. 2014;10:1581–7.

Nagata H, Worobec AS, Oh CK, Chowdhury BA, Tannenbaum S, Suzuki Y, Metcalfe DD. Identification of a point mutation in the catalytic domain of the protooncogene c-kit in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients who have mastocytosis with an associated hematologic disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10560–4.

Nakahara M, Isozaki K, Hirota S, Miyagawa J, Hase-Sawada N, Taniguchi M, Nishida T, Kanayama S, Kitamura Y, Shinomura Y, Matsuzawa Y. A novel gain-of-function mutation of c-kit gene in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1090–5.

Maeyama H, Hidaka E, Ota H, Minami S, Kajiyama M, Kuraishi A, Mori H, Matsuda Y, Wada S, Sodeyama H, Nakata S, Kawamura N, Hata S, Watanabe M, Iijima Y, Katsuyama T. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor with hyperpigmentation: association with a germline mutation of the c-kit gene. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:210–5.

Tang X, Boxer M, Drummond A, Ogston P, Hodgins M, Burden AD. A germline mutation in KIT in familial diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e88.

Ward SM, Burns AJ, Torihashi S, Sanders KM. Mutation of the proto-oncogene c-kit blocks development of interstitial cells and electrical rhythmicity in murine intestine. J Physiol. 1994;480(Pt 1):91–7.

Nocka K, Majumder S, Chabot B, Ray P, Cervone M, Bernstein A, Besmer P. Expression of c-kit gene products in known cellular targets of W mutations in normal and W mutant mice–evidence for an impaired c-kit kinase in mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1989;3:816–26.

Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang-Feng T, Coussens L, Munemitsu S, Dull TJ, Chen E, Schlessinger J, Francke U, Ullrich A. Human proto-oncogene c-kit: a new cell surface receptor tyrosine kinase for an unidentified ligand. EMBO J. 1987;6:3341–51.

Zsebo KM, Williams DA, Geissler EN, Broudy VC, Martin FH, Atkins HL, Hsu RY, Birkett NC, Okino KH, Murdock DC, et al. Stem cell factor is encoded at the Sl locus of the mouse and is the ligand for the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor. Cell. 1990;63:213–24.

Martin FH, Suggs SV, Langley KE, Lu HS, Ting J, Okino KH, Morris CF, McNiece IK, Jacobsen FW, Mendiaz EA, et al. Primary structure and functional expression of rat and human stem cell factor DNAs. Cell. 1990;63:203–11.

Lennartsson J, Blume-Jensen P, Hermanson M, Ponten E, Carlberg M, Ronnstrand L. Phosphorylation of Shc by Src family kinases is necessary for stem cell factor receptor/c-kit mediated activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and c-fos induction. Oncogene. 1999;18:5546–53.

Thommes K, Lennartsson J, Carlberg M, Ronnstrand L. Identification of Tyr-703 and Tyr-936 as the primary association sites for Grb2 and Grb7 in the c-Kit/stem cell factor receptor. Biochem J. 1999;341(Pt 1):211–6.

Serve H, Hsu YC, Besmer P. Tyrosine residue 719 of the c-kit receptor is essential for binding of the P85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol (PI) 3-kinase and for c-kit-associated PI 3-kinase activity in COS-1 cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6026–30.

Blume-Jensen P, Wernstedt C, Heldin CH, Ronnstrand L. Identification of the major phosphorylation sites for protein kinase C in kit/stem cell factor receptor in vitro and in intact cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14192–200.

Lennartsson J, Wernstedt C, Engstrom U, Hellman U, Ronnstrand L. Identification of Tyr900 in the kinase domain of c-Kit as a Src-dependent phosphorylation site mediating interaction with c-Crk. Exp Cell Res. 2003;288:110–8.

Gommerman JL, Sittaro D, Klebasz NZ, Williams DA, Berger SA. Differential stimulation of c-Kit mutants by membrane-bound and soluble Steel Factor correlates with leukemic potential. Blood. 2000;96:3734–42.

Linnekin D, DeBerry CS, Mou S. Lyn associates with the juxtamembrane region of c-Kit and is activated by stem cell factor in hematopoietic cell lines and normal progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27450–5.

Voytyuk O, Lennartsson J, Mogi A, Caruana G, Courtneidge S, Ashman LK, Ronnstrand L. Src family kinases are involved in the differential signaling from two splice forms of c-Kit. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9159–66.

Serve H, Yee NS, Stella G, Sepp-Lorenzino L, Tan JC, Besmer P. Differential roles of PI3-kinase and Kit tyrosine 821 in Kit receptor-mediated proliferation, survival and cell adhesion in mast cells. EMBO J. 1995;14:473–83.

Sun J, Pedersen M, Ronnstrand L. Gab2 is involved in differential phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling by two splice forms of c-Kit. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27444–51.

Masson K, Heiss E, Band H, Ronnstrand L. Direct binding of Cbl to Tyr568 and Tyr936 of the stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit is required for ligand-induced ubiquitination, internalization and degradation. Biochem J. 2006;399:59–67.

Sun J, Pedersen M, Bengtsson S, Ronnstrand L. Grb2 mediates negative regulation of stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit signaling by recruitment of Cbl. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3935–42.

Sun J, Pedersen M, Ronnstrand L. The D816V mutation of c-Kit circumvents a requirement for Src family kinases in c-Kit signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:11039–47.

Pedersen M, Ronnstrand L, Sun J. The c-Kit/D816V mutation eliminates the differences in signal transduction and biological responses between two isoforms of c-Kit. Cell Signal. 2009;21:413–8.

Sun J, Mohlin S, Lundby A, Kazi JU, Hellman U, Pahlman S, Olsen JV, Ronnstrand L. The PI3-kinase isoform p110delta is essential for cell transformation induced by the D816V mutant of c-Kit in a lipid-kinase-independent manner. Oncogene. 2014;33:5360–9.

Kazi JU, Agarwal S, Sun J, Bracco E, Ronnstrand L. Src-like-adaptor protein (SLAP) differentially regulates normal and oncogenic c-Kit signaling. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:653–62.

Lindblad O, Kazi JU, Ronnstrand L, Sun J. PI3 kinase is indispensable for oncogenic transformation by the V560D mutant of c-Kit in a kinase-independent manner. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:4399–407.

Ueda S, Mizuki M, Ikeda H, Tsujimura T, Matsumura I, Nakano K, Daino H, Honda Zi Z, Sonoyama J, Shibayama H, Sugahara H, Machii T, Kanakura Y. Critical roles of c-Kit tyrosine residues 567 and 719 in stem cell factor-induced chemotaxis: contribution of src family kinase and PI3-kinase on calcium mobilization and cell migration. Blood. 2002;99:3342–9.

Chian R, Young S, Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Ronnstrand L, Leonard E, Ferrao P, Ashman L, Linnekin D. Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase contributes to the transformation of hematopoietic cells by the D816V c-Kit mutant. Blood. 2001;98:1365–73.

Garcia-Montero AC, Jara-Acevedo M, Teodosio C, Sanchez ML, Nunez R, Prados A, Aldanondo I, Sanchez L, Dominguez M, Botana LM, Sanchez-Jimenez F, Sotlar K, Almeida J, Escribano L, Orfao A. KIT mutation in mast cells and other bone marrow hematopoietic cell lineages in systemic mast cell disorders: a prospective study of the Spanish Network on Mastocytosis (REMA) in a series of 113 patients. Blood. 2006;108:2366–72.

Fritsche-Polanz R, Jordan JH, Feix A, Sperr WR, Sunder-Plassmann G, Valent P, Fodinger M. Mutation analysis of C-KIT in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes without mastocytosis and cases of systemic mastocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2001;113:357–64.

Damaj G, Joris M, Chandesris O, Hanssens K, Soucie E, Canioni D, Kolb B, Durieu I, Gyan E, Livideanu C, Cheze S, Diouf M, Garidi R, Georgin-Lavialle S, Asnafi V, Lhermitte L, Lavigne C, Launay D, Arock M, Lortholary O, Dubreuil P, Hermine O. ASXL1 but not TET2 mutations adversely impact overall survival of patients suffering systemic mastocytosis with associated clonal hematologic non-mast-cell diseases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85362.

Longley BJ Jr, Metcalfe DD, Tharp M, Wang X, Tyrrell L, Lu SZ, Heitjan D, Ma Y. Activating and dominant inactivating c-KIT catalytic domain mutations in distinct clinical forms of human mastocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1609–14.

Sotlar K, Escribano L, Landt O, Mohrle S, Herrero S, Torrelo A, Lass U, Horny HP, Bultmann B. One-step detection of c-kit point mutations using peptide nucleic acid-mediated polymerase chain reaction clamping and hybridization probes. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:737–46.

Pullarkat VA, Pullarkat ST, Calverley DC, Brynes RK. Mast cell disease associated with acute myeloid leukemia: detection of a new c-kit mutation Asp816His. Am J Hematol. 2000;65:307–9.

Pignon JM, Giraudier S, Duquesnoy P, Jouault H, Imbert M, Vainchenker W, Vernant JP, Tulliez M. A new c-kit mutation in a case of aggressive mast cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1997;96:374–6.

Akin C, Fumo G, Yavuz AS, Lipsky PE, Neckers L, Metcalfe DD. A novel form of mastocytosis associated with a transmembrane c-kit mutation and response to imatinib. Blood. 2004;103:3222–5.

Nakagomi N, Hirota S. Juxtamembrane-type c-kit gene mutation found in aggressive systemic mastocytosis induces imatinib-resistant constitutive KIT activation. Lab Invest. 2007;87:365–71.

Muller AM, Duque J, Shizuru JA, Lubbert M. Complementing mutations in core binding factor leukemias: from mouse models to clinical applications. Oncogene. 2008;27:5759–73.

Soreide K, Sandvik OM, Soreide JA, Giljaca V, Jureckova A, Bulusu VR. Global epidemiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST): a systematic review of population-based cohort studies. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;40:39–46.

Orfao A, Garcia-Montero AC, Sanchez L, Escribano L, REMA. Recent advances in the understanding of mastocytosis: the role of KIT mutations. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:12–30.

Yan L, Zou L, Zhao W, Wang Y, Liu B, Yao H, Yu H. Clinicopathological significance of c-KIT mutation in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13718.

Chen LL, Trent JC, Wu EF, Fuller GN, Ramdas L, Zhang W, Raymond AK, Prieto VG, Oyedeji CO, Hunt KK, Pollock RE, Feig BW, Hayes KJ, Choi H, Macapinlac HA, Hittelman W, Velasco MA, Patel S, Burgess MA, Benjamin RS, Frazier ML. A missense mutation in KIT kinase domain 1 correlates with imatinib resistance in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5913–9.

Kikuchi H, Miyazaki S, Setoguchi T, Hiramatsu Y, Ohta M, Kamiya K, Sakaguchi T, Konno H. Rapid relapse after resection of a sunitinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor harboring a secondary mutation in exon 13 of the c-KIT gene. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4105–9.

Antonescu CR, Besmer P, Guo T, Arkun K, Hom G, Koryotowski B, Leversha MA, Jeffrey PD, Desantis D, Singer S, Brennan MF, Maki RG, DeMatteo RP. Acquired resistance to imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumor occurs through secondary gene mutation. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4182–90.

Yang Y, Letard S, Borge L, Chaix A, Hanssens K, Lopez S, Vita M, Finetti P, Birnbaum D, Bertucci F, Gomez S, de Sepulveda P, Dubreuil P. Pediatric mastocytosis-associated KIT extracellular domain mutations exhibit different functional and signaling properties compared with KIT-phosphotransferase domain mutations. Blood. 2010;116:1114–23.

Hartmann K, Wardelmann E, Ma Y, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Preussner LM, Woolery C, Baldus SE, Heinicke T, Thiele J, Buettner R, Longley BJ. Novel germline mutation of KIT associated with familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors and mastocytosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1042–6.

Wang HJ, Lin ZM, Zhang J, Yin JH, Yang Y. A new germline mutation in KIT associated with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis in a Chinese family. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:146–9.

Zhang LY, Smith ML, Schultheis B, Fitzgibbon J, Lister TA, Melo JV, Cross NC, Cavenagh JD. A novel K509I mutation of KIT identified in familial mastocytosis-in vitro and in vivo responsiveness to imatinib therapy. Leuk Res. 2006;30:373–8.

Speight RA, Nicolle A, Needham SJ, Verrill MW, Bryon J, Panter S. Rare, germline mutation of KIT with imatinib-resistant multiple GI stromal tumors and mastocytosis. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e245–7.

de Melo Campos P, Machado-Neto JA, Scopim-Ribeiro R, Visconte V, Tabarroki A, Duarte AS, Barra FF, Vassalo J, Rogers HJ, Lorand-Metze I, Tiu RV, Costa FF, Olalla Saad ST, Traina F. Familial systemic mastocytosis with germline KIT K509I mutation is sensitive to treatment with imatinib, dasatinib and PKC412. Leuk Res. 2014;38:1245–51.

Chan EC, Bai Y, Kirshenbaum AS, Fischer ER, Simakova O, Bandara G, Scott LM, Wisch LB, Cantave D, Carter MC, Lewis JC, Noel P, Maric I, Gilfillan AM, Metcalfe DD, Wilson TM. Mastocytosis associated with a rare germline KIT K509I mutation displays a well-differentiated mast cell phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:178–87.

Foster R, Byrnes E, Meldrum C, Griffith R, Ross G, Upjohn E, Braue A, Scott R, Varigos G, Ferrao P, Ashman LK. Association of paediatric mastocytosis with a polymorphism resulting in an amino acid substitution (M541L) in the transmembrane domain of c-KIT. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:1160–9.

Nakai M, Hashikura Y, Ohkouchi M, Yamamura M, Akiyama T, Shiba K, Kajimoto N, Tsukamoto Y, Hao H, Isozaki K, Hirai T, Hirota S. Characterization of novel germline c-kit gene mutation, KIT-Tyr553Cys, observed in a family with multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Lab Invest. 2012;92:451–7.

Robson ME, Glogowski E, Sommer G, Antonescu CR, Nafa K, Maki RG, Ellis N, Besmer P, Brennan M, Offit K. Pleomorphic characteristics of a germ-line KIT mutation in a large kindred with gastrointestinal stromal tumors, hyperpigmentation, and dysphagia. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1250–4.

Hirota S, Okazaki T, Kitamura Y, O’Brien P, Kapusta L, Dardick I. Cause of familial and multiple gastrointestinal autonomic nerve tumors with hyperplasia of interstitial cells of Cajal is germline mutation of the c-kit gene. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:326–7.

Beghini A, Tibiletti MG, Roversi G, Chiaravalli AM, Serio G, Capella C, Larizza L. Germline mutation in the juxtamembrane domain of the kit gene in a family with gastrointestinal stromal tumors and urticaria pigmentosa. Cancer. 2001;92:657–62.

Kuroda N, Tanida N, Hirota S, Daum O, Hes O, Michal M, Lee GH. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor with germ line mutation of the juxtamembrane domain of the KIT gene observed in relatively young women. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:358–61.

Li FP, Fletcher JA, Heinrich MC, Garber JE, Sallan SE, Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Duensing A, van de Rijn M, Schnipper LE, Demetri GD. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome: phenotypic and molecular features in a kindred. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2735–43.

Kim HJ, Lim SJ, Park K, Yuh YJ, Jang SJ, Choi J. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors with a germline c-kit mutation. Pathol Int. 2005;55:655–9.

Nishida T, Hirota S, Taniguchi M, Hashimoto K, Isozaki K, Nakamura H, Kanakura Y, Tanaka T, Takabayashi A, Matsuda H, Kitamura Y. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumours with germline mutation of the KIT gene. Nat Genet. 1998;19:323–4.

Bamba S, Hirota S, Inatomi O, Ban H, Nishimura T, Shioya M, Imaeda H, Nishida A, Sasaki M, Murata S, Andoh A. Familial and multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors with fair response to a half-dose of imatinib. Intern Med. 2015;54:759–64.

Kang DY, Park CK, Choi JS, Jin SY, Kim HJ, Joo M, Kang MS, Moon WS, Yun KJ, Yu ES, Kang H, Kim KM. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinicopathologic and genetic analysis of 12 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:224–32.

Wozniak A, Rutkowski P, Sciot R, Ruka W, Michej W, Debiec-Rychter M. Rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with a novel germline KIT mutation. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:2160–4.

Neuhann TM, Mansmann V, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Klink B, Hellinger A, Hoffkes HG, Wardelmann E, Schildhaus HU, Tinschert S. A novel germline KIT mutation (p. L576P) in a family presenting with juvenile onset of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors, skin hyperpigmentations, and esophageal stenosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:898–905.

Carballo M, Roig I, Aguilar F, Pol MA, Gamundi MJ, Hernan I, Martinez-Gimeno M. Novel c-KIT germline mutation in a family with gastrointestinal stromal tumors and cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;132A:361–4.

Jones DH, Caracciolo JT, Hodul PJ, Strosberg JR, Coppola D, Bui MM. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumor syndrome: report of 2 cases with KIT exon 11 mutation. Cancer Control. 2015;22:102–8.

Tarn C, Merkel E, Canutescu AA, Shen W, Skorobogatko Y, Heslin MJ, Eisenberg B, Birbe R, Patchefsky A, Dunbrack R, Arnoletti JP, von Mehren M, Godwin AK. Analysis of KIT mutations in sporadic and familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors: therapeutic implications through protein modeling. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3668–77.

Lasota J, Miettinen M. A new familial GIST identified. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1342.

Kleinbaum EP, Lazar AJ, Tamborini E, McAuliffe JC, Sylvestre PB, Sunnenberg TD, Strong L, Chen LL, Choi H, Benjamin RS, Zhang W, Trent JC. Clinical, histopathologic, molecular and therapeutic findings in a large kindred with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:711–8.

Pollard WL, Beachkofsky TM, Kobayashi TT. Novel R634W c-kit mutation identified in familial mastocytosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:267–70.

Yamanoi K, Higuchi K, Kishimoto H, Nishida Y, Nakamura M, Sudoh M, Hirota S. Multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors with novel germline c-kit gene mutation, K642T, at exon 13. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:884–8.

Bachet JB, Landi B, Laurent-Puig P, Italiano A, Le Cesne A, Levy P, Safar V, Duffaud F, Blay JY, Emile JF. Diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) and germline mutation of KIT exon 13. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2531–41.

Isozaki K, Terris B, Belghiti J, Schiffmann S, Hirota S, Vanderwinden JM. Germline-activating mutation in the kinase domain of KIT gene in familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1581–5.

Graham J, Debiec-Rychter M, Corless CL, Reid R, Davidson R, White JD. Imatinib in the management of multiple gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with a germline KIT K642E mutation. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1393–6.

Vilain RE, Dudding T, Braye SG, Groombridge C, Meldrum C, Spigelman AD, Ackland S, Ashman L, Scott RJ. Can a familial gastrointestinal tumour syndrome be allelic with Waardenburg syndrome? Clin Genet. 2011;79:554–60.

Hirota S, Nishida T, Isozaki K, Taniguchi M, Nishikawa K, Ohashi A, Takabayashi A, Obayashi T, Okuno T, Kinoshita K, Chen H, Shinomura Y, Kitamura Y. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with dysphagia and novel type germline mutation of KIT gene. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1493–9.

Veiga I, Silva M, Vieira J, Pinto C, Pinheiro M, Torres L, Soares M, Santos L, Duarte H, Bastos AL, Coutinho C, Dinis J, Lopes C, Teixeira MR. Hereditary gastrointestinal stromal tumors sharing the KIT Exon 17 germline mutation p.Asp820Tyr develop through different cytogenetic progression pathways. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:91–8.

O’Riain C, Corless CL, Heinrich MC, Keegan D, Vioreanu M, Maguire D, Sheahan K. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: insights from a new familial GIST kindred with unusual genetic and pathologic features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1680–3.

Thalheimer A, Schlemmer M, Bueter M, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Schildhaus HU, Buettner R, Hartung E, Thiede A, Meyer D, Fein M, Maroske J, Wardelmann E. Familial gastrointestinal stromal tumors caused by the novel KIT exon 17 germline mutation N822Y. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1560–5.

Wasag B, Niedoszytko M, Piskorz A, Lange M, Renke J, Jassem E, Biernat W, Debiec-Rychter M, Limon J. Novel, activating KIT-N822I mutation in familial cutaneous mastocytosis. Exp Hematol. 2011;39:859–65.

Miettinen M, Lasota J. KIT (CD117): a review on expression in normal and neoplastic tissues, and mutations and their clinicopathologic correlation. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2005;13:205–20.

Fritsche-Polanz R, Fritz M, Huber A, Sotlar K, Sperr WR, Mannhalter C, Fodinger M, Valent P. High frequency of concomitant mastocytosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia exhibiting the transforming KIT mutation D816V. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:335–46.

Molderings GJ. The genetic basis of mast cell activation disease—looking through a glass darkly. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;93:75–89.

Graziosi L, Marino E, Ludovini V, Rebonato A, Angelis VD, Donini A. Unique case of sporadic multiple gastro intestinal stromal tumour. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;9:98–100.

Lux ML, Rubin BP, Biase TL, Chen CJ, Maclure T, Demetri G, Xiao S, Singer S, Fletcher CD, Fletcher JA. KIT extracellular and kinase domain mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:791–5.

Bauer S, Joensuu H. Emerging agents for the treatment of advanced, imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors: current status and future directions. Drugs. 2015;75:1323–34.

Karafiat V, Dvorakova M, Pajer P, Cermak V, Dvorak M. Melanocyte fate in neural crest is triggered by Myb proteins through activation of c-kit. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2975–84.

Kawakami T, Soma Y, Kawa Y, Ito M, Yamasaki E, Watabe H, Hosaka E, Yajima K, Ohsumi K, Mizoguchi M. Transforming growth factor beta1 regulates melanocyte proliferation and differentiation in mouse neural crest cells via stem cell factor/KIT signaling. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:471–8.

Lev S, Blechman JM, Givol D, Yarden Y. Steel factor and c-kit protooncogene: genetic lessons in signal transduction. Crit Rev Oncog. 1994;5:141–68.

Mehnert JM, Kluger HM. Driver mutations in melanoma: lessons learned from bench-to-bedside studies. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:449–57.

Yun J, Lee J, Jang J, Lee EJ, Jang KT, Kim JH, Kim KM. KIT amplification and gene mutations in acral/mucosal melanoma in Korea. APMIS. 2011;119:330–5.

Ashida A, Takata M, Murata H, Kido K, Saida T. Pathological activation of KIT in metastatic tumors of acral and mucosal melanomas. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:862–8.

Nakai N, Ishikawa T, Nishitani A, Liu NN, Shincho M, Hao H, Isozaki K, Kanda T, Nishida T, Fujimoto J, Hirota S. A mouse model of a human multiple GIST family with KIT-Asp820Tyr mutation generated by a knock-in strategy. J Pathol. 2008;214:302–11.

Sommer G, Agosti V, Ehlers I, Rossi F, Corbacioglu S, Farkas J, Moore M, Manova K, Antonescu CR, Besmer P. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in a mouse model by targeted mutation of the Kit receptor tyrosine kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:6706–11.

Rubin BP, Antonescu CR, Scott-Browne JP, Comstock ML, Gu Y, Tanas MR, Ware CB, Woodell J. A knock-in mouse model of gastrointestinal stromal tumor harboring kit K641E. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6631–9.

Authors’ contributions

JS and HK searched articles, designed the review and drafted the manuscript. UK and HZ edited and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

The work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81660473), Ningxia Medical University foundation No. XZ2016001 (JS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ke, H., Kazi, J.U., Zhao, H. et al. Germline mutations of KIT in gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and mastocytosis. Cell Biosci 6, 55 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-016-0120-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13578-016-0120-8