Abstract

To date, the microbiological quality of river sediments and its impact on water resources are not included in the water quality monitoring assessment. Therefore, the aim of this study was to establish genetic relatedness between faecal coliforms and enterococci isolated from the river water and riverbed sediments of Apies River to better understand the genetic similarity of microorganisms between the sediment and water phases. Indicator bacteria were subjected to a molecular study, which consisted of PCR amplification and sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA gene using specific primers for faecal coliforms and enterococci, respectively. Results revealed that the Apies River had high faecal pollution levels with enterococci showing low to moderate correlation coefficient (r2 values ranged from 0.2605 to 0.7499) compared to the faecal coliforms which showed zero to low correlation (r2 values ranged from 0.0027 to 0.1407) indicating that enterococci may be better indicator than faecal coliforms for detecting faecal contamination in riverbed sediments. The phylogenetic tree of faecal coliforms revealed a 98% homology among their nucleotide sequences confirming the close genetic relatedness between river water and riverbed sediment isolates. The phylogenetic tree of the enterococci showed that Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are the predominant species found in both river water and riverbed sediments with bootstrap values of ≥99%. A high degree of genetic relatedness between sediment and water isolates indicated a possible common ancestry and transmission pathway. We recommend the microbial monitoring of riverbed sediments as it harbours more diverse microbial community and once resuspended may cause health and environmental problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The South African government has implemented regulations and policies to deliver safe water to all; however, based on the figures given in the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) Report 2013, 3–5 million people in South Africa still lack access to an improved water source (UN 2013). Many families in southern Africa including South Africa and especially those residing in non-metropolitan areas still rely on river water for drinking and other domestic purposes (Donovan et al. 2008; Abhirosh et al. 2010). Microbiological contamination of drinking water is one of the main causes in the spread of waterborne diseases (Franz 2005). Monitoring of riverbed sediments worldwide typically focuses on the analysis of the levels of chemical contaminants (Guerra et al. 2009), whereas the risks posed by the presence of pathogenic microorganisms within the sediment compartment are largely disregarded (Luna et al. 2010). Sediment re-suspension into the water column may cause debilitating waterborne diseases in individuals, particularly immunocompromised individuals (Elliot and Colwell 1985).

The degree of risk associated with waterborne pathogens is certainly high with the knowledge that pathogens can grow within the sediment compartments of aquatic systems (Jamieson et al. 2004). This risk can be exacerbated by current microbial monitoring policies which do not consider the phases of pathogens associated with aquatic sediments. Furthermore, there is a general lack of understanding of the nature and relevance of pathogen and sediment association and the risks of infection due to exposure of people to the pathogens mobilised from sediments, as well as pathogen viability, transport, and fate within aquatic systems (Droppo et al. 2009). Bacteria often show an affinity for sediment attachment (Liss et al. 1996; Jamieson et al. 2004) as sediments represent a beneficial environment for nutrient, food assimilation and protection from environmental stress such as contaminants and predation. Increasing evidence indicates that many marine sediments (stream substrates) serve as reservoir of pathogenic microorganisms of faecal origin (e.g. Escherichia and Enterococcus), including pathogenic and virulent strains of bacteria (Alm et al. 2003; Luna et al. 2010). The presence of these faecal bacteria poses serious concerns for the quality of aquatic systems as well as for human health, especially when sediments undergo re-suspension due to both natural and anthropogenic disturbances (Luna et al. 2012).

Several methods for studying genetic similarity have been developed throughout the years. Subsequently, some housekeeping genes such as the highly conserved 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes have been used. In spite of the fact that the outright rate of progress in the 16S rRNA gene evolution is not known, it marks evolutionary distance and similarity of organisms (Thorne et al. 1998). Others have found the utilisation of 23S rRNA groupings supportive in recognising similarity among Streptococcus spp. (Rantakokko-Jalava et al. 2000). Although few scientists agree on sole use of 16S rRNA gene sequences (Roth et al. 1998), others view the combination of 16S and 23S rRNA gene grouping as a great tool for phylogenetic analysis (Song et al. 2004).

Genetic similarity has been used widely in molecular microbiology and heredity studies in order to confirm molecular information gathered on pathogenic strains to establish their relationship with other bacteria isolated from different sources, such as that between clinical specimens and environmental isolates (Shayegani et al. 1991; Rood et al. 2011; Salama et al. 2012; Njage and Buys 2015). To date, the phylogenetic relationship has been used to reveal similarity among microbial isolates from many targets: food (van Megen et al. 2009); soil (Pester et al. 2012) and wastewater (Steinberg and Regan 2008), but as yet little is known about the genetic similarity between indicator bacteria of aquatic systems and those of riverbed sediments.

The aim of the present study was to establish the genetic similarity between faecal coliforms and enterococci isolated from river water and riverbed sediments of the Apies River.

Materials and methods

Study area

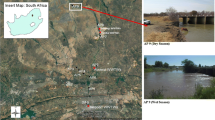

The Apies River is located in Pretoria in the Gauteng Province of South Africa and it is one of Tshwane’s significant natural resources. The river rises in the Fountains Valley, Pretoria and flows through Gauteng, North–West and Limpopo Provinces to ultimately join the Limpopo River. It falls within the Crocodile (West) Marico Water Management Area and has a total flow >500 m3 per year, which is controlled by diverse processes such as the treated effluents from four wastewater treatment works, the extraction of water for different usages and the total rainfall and runoff reaching the river. These wastewater treatment works discharge their treated effluents to the river and contribute roughly 12% of the stream flows. A number of land-use activities along the river starting from Pretoria Central, Arcelor-Mittal Steelworks in Pretoria-West and substantial parts of Atteridgeville contribute to the lower microbiological quality of this river (RHP RHP (River Health Programme) 2005; Abia et al. 2015c). Figure 1 illustrates various sites for the collection of water and sediment samples during the study. UP (upstream Daspoort Wastewater treatment plant-WWTP); SP: Skinner Spruit, effluent from Atteridgeville; DD1: downstream Daspoort Site 1, mixing point between Apies River and Skinner Spruit; DD2: downstream Daspoort Site 2, 1 km from the Daspoort WWTP; DD3: downstream Daspoort Site 3, 3 km from the Daspoort WWTP).

Collection of water and sediment samples

A total of five sampling sites were selected along the river as illustrated in Fig. 1. The sampling programme was performed on a weekly basis from August to November 2014. Water samples were collected using sterile plastic containers, by wading out to a depth of 0.1 m, midway between the banks following standard procedures (US EPA 2002a, b). Grab sediment samples were collected from the top 5 cm of the riverbed at each sampling site, using a sterile polypropylene scoop and transferred to sterile 100 mL polypropylene containers with lids. All the samples were transported to the laboratory at 4 °C in cooler-boxes containing ice and analysed within 3 h of collection.

Enumeration of culturable faecal coliforms and Enterococcus species

The membrane filtration technique was utilised for the cultivation and enumeration of faecal coliforms and Enterococcus spp. for both river water and riverbed sediments, following procedures described by Luna et al. (2010). The Chromocult® Coliform agar (Merck) and Chromocult® Enterococci agar (Merck) were used, respectively. In this study, the water displacement method previously described by Abia et al. (2015a) was used to quantify the target bacteria in the sediments, instead of the common approach (weighting method). Briefly; this approach which is based on Archimedes’ principle consist of gradually transferring sediment samples were into a graduated 1 L Durham bottle containing 900 mL of 1× PBS until the 1000 mL mark was reached to obtained a 10% dilution (v/v). Thereafter the suspension was vigorously hand shaken for 2 min as described by Abia et al. (2015a). The water displacement method, which is important to detach connected microorganisms from the sediment matrix and for the subsequent filtration step onto membranes, does not influence the growth of target bacteria (Abia et al. 2015a). This method was developed in order to better compare microbial counts of sediment and water with one unit (CFU/100 mL) since other studies (Alm et al. 2003; Fries et al. 2008) expressed water and sediment in different units such as MPN GDW or CFU GDW versus CFU/100 mL. One hundred millilitres of aliquots, along with tenfold serial dilutions of the resulting phosphate buffer solution were then analysed using the membrane filtration technique according to standard methods (US EPA 2002a, b). For faecal coliforms, plates were incubated for 24 h at 44.5 °C and for Enterococcus spp., plates were incubated for 24–48 h at 37 °C. According to Abia et al. (2015a), results obtained from riverbed sediments by water displacement methods for faecal coliform and Enterococcus spp. counts were reported as colony-forming units (CFUs) per 100 mL of sediment suspension in PBS and for river water as CFU/100 mL (Abia et al. 2015a).

Molecular analysis of faecal coliforms and Enterococcus species

For the molecular analysis of bacterial isolates, five colonies per plate was randomly selected based on colony appearance. Isolated bacteria were preserved in 15% glycerol at 0 °C for molecular analysis.

Total genomic DNA extraction of faecal coliforms and Enterococcus spp

A total of 53 isolates (14—water and 15—sediment faecal coliforms isolates and 12—water and 12 sediments Enterococcus spp. isolates) were used for the molecular study. The preserved bacteria were allowed to thaw, and then centrifuged for 1 min at 12,000 r/min. Total genomic DNA was extracted from the bacterial pellets using the InstaGene™ matrix (Bio-Rad, South Africa) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality and the quantity of the isolated nucleic acids were determined using the NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific) and 1% agarose gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, South Africa).

PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene of E. coli and 23S rRNA of Enterococcus spp

For the amplification process, the following primer sets were used: 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1507R (5′-CGGGTAACGTCAATGAGCAAA-3′) targeting the 16S rDNA of faecal coliforms (Lane 1991; Heyndrickx et al. 1991); ENT765F (5′-TCTCATCGGCTCCTACCTATC-3′) and ENT1699R (5′-AAGCTGTGGACTACACCATTAG-3′) targeting the 23S rRNA of Enterococcus spp. Reactions were run using SsoFast™ EvaGreen® Supermix (Bio-Rad, South Africa) containing 2× reaction buffer with dNTPs, Sso7d-fusion, polymerase, MgCl2 and EvaGreen dye and in a resulting volume of 20 µL, consisting of 10 µL of Supermix, 0.5 µL of each primer (concentration 500 µM), 10 ng of isolated gDNA template and 4 µL nuclease-free water (Fermentas, 140 Leon-Rot, Germany). The PCR reactions were carried out in a CFX96™ Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, South Africa), and the following thermal cycling conditions were used: enzyme activation step at 98 °C for 2 min, followed by 40 amplification cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 5 s annealing of primers with the gDNA template at 59 °C for faecal coliforms and 54 °C for Enterococcus spp., and a primer extension at 72 °C for 2 min. The specificity of the assay was assessed by the analysis of the melting curve (Fey et al. 2004; Varga and James 2005). Melting curve analysis was performed from 59 °C for faecal coliforms and from 54 °C for Enterococcus spp. up to 95 °C with increments of 0.5 °C per 10 s. The melting temperature was defined as the peak of fluorescence in the generated melting curve.

Gel electrophoresis

The PCR products were loaded on 1% (w/v) agarose gel for electrophoresis and then stained with ethidium bromide, followed by visualisation under ultraviolet light. The FastRuler Middle Range DNA Ladder (Fermantas) was included in all gels as a size marker. These results were captured using a gel documentation system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK).

Sequencing of the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes and sequence analysis

Following the PCR reaction, 29 amplicons for faecal coliforms and 24 amplicons for Enterococcus spp. were sequenced using the conventional Sanger (dideoxy) sequencing in the forward direction using the primers described above. Prior to sequencing, the DNA products were purified using PCR clean up kit (Biocombiotech, South Africa) and check for quality using NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo scientific). For sequencing procedure, “BigDye” for ABI3130XL was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions and the gel was run on a 3130XL sequencer. Sequences were analysed by comparing them with known 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA sequences using the BLASTn algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to find the closest match in GenBank, EMBL, DDBJ, and PDB sequence data. Most similar type species that showed 97% sequence similarity with the isolates were selected as identical species. The 16S rRNA faecal coliform and 23S rRNA enterococci sequences were aligned by Clustal X2 (Larkin et al. 2007) and were then edited using BioEdit v.7.2.5 software (Hall 1999). The distances for each 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA were calculated by the neighbour-joining method (Tamura et al. 2004) and phylogenetic trees were created by using MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2013). The evolutionary distances for each 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA were calculated by the neighbour-joining method with Kimura 2-parameter model by 500 replicates (Tamura et al. 2004). All locations having gaps and missing data were removed from the data set using the complete-deletion option.

All the newly sequenced bacteria were deposited in the DNA Database of Japan with the accessions number listed in the Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

The data were statistically analysed using the IBM SPSS Software (v.22) and Microsoft Excel 2010. The bacterial counts of the river water and riverbed sediment samples were assessed for differences by using a two-way ANOVA with a 95% confidence interval. Spearman’s rank correlation (a non-parametric test of correlation) was used to analyse differences or correlations in the datasets for faecal indicators between water and sediment samples. A Student’s t test was used to investigate any statistically significant differences between the mean values of the microbial loads.

Results

The differences in faecal coliform (Fig. 2a) and enterococci (Fig. 2b) loads between river water and riverbed sediment were observed. Sediment faecal coliform counts were consistently higher than water faecal coliform counts at all sites during the entire sampling period. Faecal coliforms were more abundant than Enterococcus with mean concentrations of 7.60 log10 and 6.38 log10 CFU/100 mL respectively for riverbed sediment and mean concentration of 3.09 log10 CFU/100 mL and 3.97 log10 CFU/100 mL for river water. Furthermore, the faecal coliform concentrations in the riverbed sediments were significantly higher than in their corresponding overlying water for all sites tested for faecal coliform (UP p < 0.05; SP p < 0.05; DD1 p < 0.05; p < 0.05; DD3 p < 0.05) and Enterococci (UP p < 0.05; SP p < 0.05; DD1 p < 0.05; DD2 p < 0.05; DD3 p < 0.05).

Correlation analysis was used to determine the relationship between river water and riverbed sediment counts at different sampling points along the Apies River. The Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients and the corresponding levels of significance (p values) for the different parameters was also evaluated. For faecal coliforms, 0–0.14 correlation coefficient between river water and riverbed sediment samples were observed in (Table 1).

Genetic similarity

The PCR amplification products for the faecal coliforms and enterococci isolated from river water when contrasted with those isolated from riverbed sediments showed a similarity in amplified regions. These results suggest that indicator bacteria isolated from river water might have potential similarity to riverbed sediment isolates. All the samples displayed a single band of 1 500 bp (base pairs) in agarose gel for faecal coliforms and 956 bp for enterococci, indicating the successful amplification of the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA gene sequence from the isolates.

The evolutionary history was established utilising the neighbour-joining algorithm (Saitou and Nei 1987) and the optimal tree with the sum of the branch lengths (0.87639720 for faecal coliforms and 2.67726379 for Enterococcus spp.) were obtained (Figs. 3, 4). The evolutionary distances were calculated utilising the Kimura-2 parameter method (Kimura 1980) and are in the units of the number of base replacements per location. The analysis involved 29 faecal coliforms and 24 Enterococcus spp. nucleotide sequences. First, second and third codon positions were included, while all positions containing crevices and missing information were eliminated from the dataset. A total of 318 (faecal coliform) and 545 (Enterococcus spp.) positions were identified in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were performed in MEGA 6 (Tamura et al. 2013). All fragments from the phylogenetic tree belonged to the Enterobacteriaceae family for faecal coliforms and to the Enterococcaceae family for enterococci. The sequences recovered from the NCBI nucleotide sequence database that supplied the closest match in pair-wise BLASTn were identified as E. coli, Citrobacter, Cronobacter, Klebsiella, Serratia, Enterobacter and Comamonas for faecal coliform sequences and Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium for enterococci sequences.

Phylogenetic tree of faecal coliform bacteria isolated from river water (blue) and riverbed sediment (red) constructed using MEGA 6 with the Neighbor-Joining method-distance Kimura 2, for a 1500 bp fragment of the 16S rRNA coding region of the Faecal coliform bacteria. Numbers above branches show bootstrap values expressed as percentages of 100 replications and distribution of the genetic profiles isolated from different sites of the Apies River

Phylogenetic tree of Enterococcus bacteria isolated from river water (blue) and riverbed sediment (red) constructed using MEGA 6 with the Neighbor-Joining method-distance Kimura 2, for a 934 bp fragment of the 23S rRNA coding region of the Enterococcus spp. Numbers above branches show bootstrap values expressed as percentages of 100 replications and distribution of the genetic profiles isolated from different sites of the Apies River

Figure 3 shows the phylogenetic analysis of the faecal coliforms in both the river water and riverbed sediment. Escherichia coli (65.52%) was the predominant faecal coliform isolated in the Apies River samples, followed by Citrobacter (13.79%), Cronobacter (6.89%), Klebsiella (3.45%), Serratia (3.45%), Enterobacter (3.45%), and Comamonas (3.45%). The results showed that E. coli occurred abundantly in the river water, and clusters of E. coli with closely related strains were identified in riverbed sediment samples, while Klebsiella; Serratia and Comamonas were isolated only from the riverbed sediment samples.

Discussion

Concentration of faecal coliforms and Enterococcus spp. in water and sediments of Apies River demonstrates that the river receives high loads of external faecal pollution. This study also revealed significant differences in faecal coliforms and Enterococcus spp. loads between the Apies River sediment and water samples. These findings corroborate those of Abia et al. (2015b, c) who reported high E. coli levels in water and riverbed sediments of Apies River. The abundance of E. coli in Apies River sediments measured by membrane filtration in the present study were comparable to those of Colilert®-18 methods previously reported in riverbed sediments of the Apies River (Abia et al. 2015c). Walk et al. (2007) have also outlined the survival and growth of faecal bacteria in aquatic sediments and also pointed out that sediments may represent their secondary habitat after the intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals which serves as their primary habitat. Sediments can be “reservoirs” of metabolically active faecal indicator bacteria (Pianetti et al. 2004). This has also been confirmed by studies conducted in subtropical areas, where E. coli and enterococci displayed higher growth and survival rates in marine sediments than in the overlying seawater (Hartz et al. 2008). When bacteria enter the river, they may form flocs and settle in the bottom of rivers by adhering to sand, rocks, and other particulate matter where they can live and thrive for long periods of time (Craig et al. 2004). This causes the faecal coliforms and enterococci loads in the sediment to be higher than in the overlying water, except during heavy rainfall and runoff events when the load of bacteria in the water increases prior to settling out into the sediment (Orear and Dalman 2011).

Stumpf et al. (2010) examined the input of faecal coliforms during storm flow and base flow, and observed that during storm flow the bacterial load on average was 30–37 times greater than the base flow bacterial loads. Further, the sediment E. coli counts reached log10 2.89 CFU/100 mL, well above the EPA proposed safe limit of log10 2.37 CFU/100 mL, and hence sediment acted as a reservoir and source of faecal contamination to the overlying water (Stumpf et al. 2010). Similar results were seen in the Apies River study where sediment faecal coliform counts were as high as log10 7.61 CFU/100 mL. At this concentration and also taking into consideration re-suspension, the findings of this study suggest sediments in Apies River to be a major source of bacterial contamination during periods of low river flow. When sediment and water faecal coliform levels were compared, it was found that on average the bacterial concentration in the sediment was 1- to 3000-folds higher than in the overlying water. Sediments consistently had faecal coliform concentrations that ranged from 1 to 383 times greater than the adjacent water column (Orear and Dalman 2011). In our study, only 21.9% of all the water samples analysed were found to fall within the target water quality range (TWQR) as set out in the South African Water Quality Guidelines for Domestic Water Use (Volume 1) and for Recreational Water Use (Volume 2) (DWAF 1996). In terms of the national standards set by SANS 241 (SABS 2006) and the South African Water Quality Guidelines (Volume 1) (DWAF 1996), the limit for faecal coliforms is 0 CFU/100 mL for water that is meant for domestic use; any concentration ≥500 CFU/100 mL in drinking water can lead to gastrointestinal (GI) illness. For recreational activities the minimum acceptable risk is 8.5% GI illness risk in terms of the microbiological indicators given in the South African Water Quality Guidelines (Volume 2) (DWAF 1996). The Skinner Spruit (SP) water and sediment close to the Daspoort WWTP recorded the highest levels of both faecal coliform and Enterococcus spp. According to the most recent South African Green Drop Progress Report (DWA 2012), this treatment plant with a microbiological compliance level of 87.3% has been treating the wastewater adequately, while the Skinner Spruit, a tributary of the Apies River, is reported to carry elevated microbial loads and thus negatively impacts the water quality of the effluent discharged by this WWTP. High counts were also observed after rainfall events, confirming the findings of Pandey et al. (2012) where a sudden increase in faecal coliform counts is mostly the result of both surface water run-off and re-suspension of the stream bottom sediment.

The enterococci levels found in water were 2–4 logs lower than those found in riverbed sediment. These counts were consistently higher than those of faecal coliforms during the entire sampling period in Fig. 2b. Ferguson et al. (2005) found enterococci to be present in all the samples taken for the study conducted. The geometric mean enterococci concentrations in sediment samples were also higher (log10 3.77 CFU/10 g) than the faecal coliform concentrations (log10 3.27 CFU/10 g). Their occurrence in both water and sediment may suggest a movement between these two environments.

Unlike in other studies, the number of faecal coliforms enumerated from the riverbed sediment samples did not correlate with those enumerated from the river water samples (Craig et al. 2004). A similar attempt to correlate E. coli densities in water and in sediment by Valiela et al. (1991), An et al. (2002) and Byappanahalli et al. (2006) was also not successful. This indicated that the faecal coliform densities in water did not relate with the densities in riverbed sediments, leaving the Enterococcus spp. to be more related faecal indicators of riverbed sediment. Many studies have proven the Enterococcus spp. standard to be the more sensitive compared to faecal coliforms for recreational purposes (Noble et al. 2003; Benedict and Neumann 2004; Neumann et al. 2006).

The faecal coliforms isolated exhibit a 98% nucleotide sequence homology which emphasises the positive correlation between faecal coliforms in river water and riverbed sediment, as also reported earlier (Grant et al. 2001; Boehm et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2004; Noble and Xu 2004). However, these results can also imply a common ancestry and thus likely derived from the same source. Using the phylogenetic tree, Njage and Buys (2015) reported the genetic similarity between commensal and pathogenic E. coli strains from lettuce and irrigation water, even at a distance of 246 km apart.

Unlike faecal coliforms, the phylogenetic tree of enterococci, shown in Fig. 4, revealed that Enterococcus faecalis was the predominant species found in all the river water and riverbed sediment samples, findings corroborating those of Ferguson et al. (2005). With a bootstrap value of 100%, this may suggest that Enterococcus spp. isolated from river water and riverbed sediment samples may be highly similar at the molecular level. Anderson et al. (1997) found that enterococci of marine sediment were suggestive of natural or environmental sources of contamination to overlying water.

Microbial loads of faecal coliforms and enterococci in Apies River revealed a river that is highly polluted with faecal contamination. There is thus a need to rehabilitate or restore this stream to its once pristine state. The correlation coefficient study revealed enterococci counts to be the better indicator than faecal coliforms in search of predicting the degree of contamination in the event of riverbed sediment re-suspension. The present study revealed a high prevalence of faecal indicator bacteria and provided evidence of the close genetic similarity between isolates from river water and riverbed sediment. A 98% homology among the nucleotide sequences between river water and riverbed sediment isolates indicated their close genetic similarity. There is therefore a need to incorporate sediment quality monitoring as an integral component of the nationwide routine surface water quality monitoring programmes. This study recommends future studies to be conducted on a multi-locus sequencing or whole genome sequencing techniques in order to emphasize or reject the finding of this study.

Abbreviations

- 16S rRNA:

-

sixteen subunit ribosomal RNA

- 23S rRNA:

-

twenty-three subunit ribosomal RNA

- BLASTn:

-

basic location alignment search tool for nucleotide

- CFU GDW:

-

colony-forming units per gram dry weight

- CFU GWW:

-

colony-forming units per gram wet weight

- CFU:

-

colony forming unit

- DDBJ:

-

DNA Data Bank of Japan

- DNA:

-

deoxyribose nucleic acid

- EMBL:

-

European Molecular Biology Laboratory

- gDNA:

-

genomic DNA

- MDG:

-

millennium development goals

- MEGA6:

-

Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6

- MF:

-

membrane filtration

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- MPN GDW:

-

most probable number per gram dry weight

- RHP:

-

river health program

- TUT:

-

Tshwane University of Technology

- UN:

-

united nations

- UP:

-

upstream Daspoort Wastewater treatment plant-WWTP

- US EPA:

-

United States Environmental Protection Agency

- WWPT:

-

wastewater treatment plant

References

Abhirosh C, Sherin V, Thomas A (2010) Potential exposure risk associated with the high prevalence and survival of indicator and pathogenic bacteria in the sediment of Vembanadu Lake, India. Water Qual Expo Health 2:105–113

Abia LKA, Ubomba-Jaswa E, du Preez M, Momba MNB (2015a) Riverbed sediments in the Apies River, South Africa: recommending the use of both Clostridium perfringens and Escherichia coli as indicators of faecal pollution. J Soils Sediments 12:2412–2424

Abia LKA, Ubomba-Jaswa E, Momba MNB (2015b) Impact of seasonal variation on Escherichia coli concentrations in the riverbed sediments in the Apies River, South Africa. Sci Total Environ 537:462–469

Abia LKA, Ubomba-Jaswa E, Ssemakalu CC, Momba MNB (2015c) Development of a rapid approach for the enumeration of Escherichia coli in riverbed sediment: case study, the Apies River, South Africa. J Soils Sediments 15:2425–2432

Alm EW, Burke J, Spain A (2003) Faecal indicator bacteria are abundant in wet sand at freshwater beaches. Water Res 37:3978–3982

An YJ, Kampbell DH, Breidenbach GP (2002) Escherichia coli and total coliforms in water and sediments at lake marinas. Environ Pollut 120(3):771–778

Anderson SA, Turner SJ, Lewis GD (1997) Enterococci in the New Zealand environment: implications for water quality monitoring. Water Sci Technol 35:325–331

Benedict RT, Neumann CM (2004) Assessing Oregon’s twenty-six coastal beach areas for recreational water quality standards. Mar Pollut Bull 49:624–629

Boehm AB, Sanders BF, Winant CD (2002) Cross-shelf transport at Huntington Beach. Implications for the fate of sewage discharged through an offshore ocean outfall. Environ Sci Technol 36:1899–1906

Byappanahalli MN, Whitman RL, Shively DA, Sadowsky MJ, Ishii S (2006) Population structure, persistence, and seasonality of autochthonous Escherichia coli in temperate, coastal forest soil from a Great Lakes watershed. Environ Microbiol 8:504–513

Craig DL, Fallowfield HJ, Cromar NJ (2004) Use of microcosms to determine persistence of Escherichia coli in recreational coastal water and sediment and validation with in situ measurements. J Appl Microbiol 96:922–930

Donovan EP, Staskal DF, Unice KM, Roberts JD, Haws C, Finley BL, Harris MA (2008) Risk of gastrointestinal disease associated with exposure to pathogens in the sediments of the Lower Passaic River. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:1004–1018

Droppo IG, Liss SN, Williams D, Nelson T, Jaskot C, Trapp B (2009) Dynamic existence of waterborne pathogens within river sediment compartments. Implications for water quality regulatory affairs. Environ Sci Technol 43:1737–1743

DWA (Department of Water Affairs) (2012) 2012 Green Drop Progress Report. Department of Water Affairs, Pretoria

DWAF (1996) The South African Water Quality Guidelines (2nd edn) Volume 1: domestic water use; and Volume 2: recreational water use. Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Pretoria

Elliot EL, Colwell RR (1985) Indicator organisms for estuarine and marine waters. FEMS Microbiol Rev 1(2):61–79

Ferguson DM, Moore DF, Getrich MA, Zhowandai MH (2005) Enumeration and speciation of enterococci found in marine and intertidal sediments and coastal water in southern California. J Appl Microbiol 99:598–608

Fey A, Eichler S, Flavier S, Christen R, Hofle MG, Guzman CA (2004) Establishment of a real-time PCR-based approach for accurate quantification of bacterial RNA targets in water, using Salmonella as a model organism. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:3618–3623

Franz A (2005) A performance study of ceramic candle filter in Kenya including tests for coliphage removal. M. Eng. Thesis. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge

Fries JS, Characklis GW, Noble RT (2008) Sediment-water exchange of Vibrio spp. and faecal indicator bacteria: implications for persistence and transport in the Neuse River Estuary, North Carolina, USA. Water Res 42(4):941–950

Grant SB, Sanders BF, Boehm AB, Redman JA, Kim JH, Mrse RD, Chu AK, Gouldin M, McGee CD, Gardiner NA, Jones BH (2001) Generation of enterococci bacteria in a coastal saltwater marsh and its impact on surf zone water quality. Environ Sci Technol 35:2407–2416

Guerra R, Pasteris A, Ponti A (2009) Impacts of maintenance channel dredging in a northern Adriatic coastal lagoon I: effects on sediment properties, contamination and toxicity. Est Coast Shelf Sci 85:134–142

Hall TA (1999) BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucl Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98

Hartz AM, Cuvelier K, Nowosielski TD, Bonilla M, Green N, Esiobu DS, McCorquodale A, Rogersond A (2008) Survival potential of Escherichia coli and enterococci in subtropical beach sand: implications for water quality managers. J Environ Qual 37:898–905

Heyndrickx MP, De Vos A, De Ley J (1991) Fermentation characteristics of Clostridium pasteurianum LMG 3285 grown on glucose and mannitol. J Appl Bacteriol 70:52–58

Jamieson R, Gordon R, Joy D, Lee H (2004) Assessing microbial pollution of rural surface waters: a review of current watershed scale modeling approaches. Agric Water Manage 70:1–17

Kim JH, Grant SB, McGee CD, Sanders BF, Largier JL (2004) Locating sources of surf zone pollution: a mass budget analysis of fecal indicator bacteria at Huntington Beach, California. Environ Sci Technol 38:2626–2636

Kimura M (1980) A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol 16:111–120

Lane DJ (1991) 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M (eds) Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics. Wiley, Chichester, pp 115–175

Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Bown NP, Chenna R, Mcgettigan PA, Gibson TJ, Lopez R, Mcwilliam H, Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Valentin F, Zallace I (2007) Clustal W and clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948

Liss SN, Droppo IG, Flannigan DT, Leppard GG (1996) Floc architecture in wastewater and natural riverine systems. Environ Sci Technol 30:680–686

Luna GM, Vignaroli C, Rinaldi C, Pusceddu A, Nicoletti L, Gabellini M, Danovaro R, Biavasco F (2010) Extraintestinal Escherichia coli carrying virulence genes in coastal marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5659–5668

Luna GM, Dell’Anno A, Pietrangeli B, Danovaro R (2012) A new molecular approach based on qPCR for the quantification of fecal bacteria in contaminated marine sediments. J Biotechnol 157:446–453

Neumann CM, Harding AK, Sherman JM (2006) Oregon Beach Monitoring Program: bacterial exceedances in marine and freshwater creeks/outfall samples, October 2002–April 2005. Mar Pollut Bull 52:1270–1277

Njage PM, Buys EM (2015) Pathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli from irrigation water show potential in transmission of extended spectrum and AmpC β-lactamases determinants to isolates from lettuce. Microbiol Biotechnol 8:462–473

Noble M, Xu J (2004) Huntington Beach shoreline contamination investigation, phase III, final report: coastal circulation and transport patterns: the likelihood of OCSD’s plume impacting the Huntington Beach, CA shoreline. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2004-1019

Noble RT, Moore DF, Leecaster MK, McGee CD, Weisberg SB (2003) Comparison of total coliform, faecal coliform, and Enterococcus bacterial indicator response for ocean recreational water quality testing. Water Res 37:1637–1643

Orear RW, Dalman NE (2011) The persistence of riverbed bacterial stores and their disruption by human recreation. Proceedings of the 2011 Georgia Water Resources Conference, 11–13 April 2011, Athens

Pandey PK, Soupir ML, Rehmann CR (2012) A model for predicting re-suspension of Escherichia coli from streambed sediments. Water Res 46:115–126

Pester M, Rattei T, Flechl S, Gröngröft A, Richter A, Overmann J, Wagner M (2012) amoA-based consensus phylogeny of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and deep sequencing of amoA genes from soils of four different geographic regions. Environ Microbiol 14:525–539

Pianetti A, Bruscolini F, Sabatini L, Colantoni P (2004) Microbial characteristics of marine sediments in bathing area along Pesaro-Gabicce coast (Italy): a preliminary study. J Appl Microbiol 97:682–689

Rantakokko-Jalava K, Nikkari S, Jalava J, Eerola E, Skurnik M, Meurman O, Ruuskanen O, Alanen A, Kotilainen E, Toivanen P, Kotilainen P (2000) Direct amplification of rRNA genes in diagnosis of bacterial infections. J Clin Microbiol 38:32–39

RHP (River Health Programme) (2005) State-of-Rivers Report: monitoring and managing the ecological state of rivers in the crocodile (West) Marico water management area. Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Pretoria

Rood IG, de Korte D, Savelkoul PH, Pettersson A (2011) Molecular relatedness of Propionibacterium species isolated from blood products and on the skin of blood donors. Transfusion 51:2118–2124

Roth A, Fischer M, Hamid ME, Michalke S, Ludwig W, Mauch H (1998) Differentiation of phylogenetically related slowly growing mycobacteria based on 16S–23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer sequences. J Clin Microbiol 36:139–147

SABS (2006) South African National Standard (SANS) 241: specifications for drinking water. South African Bureau of Standards (SABS), Pretoria

Saitou N, Nei M (1987) The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425

Salama MS, Abu Shady HM, El-Gameal M, El Anany MG, Abd-El-Rehem GM (2012) Molecular study on relatedness between clinical and tap water isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in two burn units. Life Sci J Acta Zhengzhou Univ Overseas Version 9:662–666

Shayegani MEHDI, Parsons LM, Waring AL, Donhowe JOHN, Goering R, Archinal WA, Linden J (1991) Molecular relatedness of Staphylococcus epidermidis isolates obtained during a platelet transfusion-associated episode of sepsis. J Clin Microbiol 29:2768–2773

Song J, Lee SC, Kang JW, Baek HJ, Suh JW (2004) Phylogenetic analysis of Streptomyces spp. isolated from potato scab lesions in Korea on the basis of 16S rRNA gene and 16S–23S rDNA internally transcribed spacer sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 54:203–209

Steinberg LM, Regan JM (2008) Phylogenetic comparison of the methanogenic communities from an acidic, oligotrophic fen and an anaerobic digester treating municipal wastewater sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:6663–6671

Stumpf CH, Piehler MF, Thompson S, Noble RT (2010) Loading of fecal indicator bacteria in North Carolina tidal creek headwaters: hydrographic patterns and terrestrial runoff relationships. Water Res 16:4704–4715

Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S (2004) Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:11030–11035

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol 30:2725–2729

Thorne JL, Kishino H, Painter IS (1998) Estimating the rate of evolution of the rate of molecular evolution. Mol Biol Evol 15:1647–1657

UN (United Nations) (2013) The Millennium Development Goals Report 2013. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2013. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN-DESA). United Nations, New York

US EPA (2002a) Method 1600: Enterococci in water by membrane filtration using membrane-Enterococcus indoxyl-ß-d-glucoside agar (mEI). United States Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC

US EPA (2002b) Method Escherichia coli (E. coli) in water by membrane filtration using modified membrane-thermotolerant Escherichia coli Agar (Modified mTEC). United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) Office of Water, Office of Science and Technology, Washington DC

Valiela I, Alber M, LaMontagne M (1991) Fecal coliform loadings and stocks in Buttermilk Bay, Massachusetts, USA, and management implications. Environ Manag 15:659–674

van Megen H, van den Elsen S, Holterman M, Karssen G, Mooyman P, Bongers T, Helder J (2009) A phylogenetic tree of nematodes based on about 1200 full-length small subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. J Nematol 11:927–950

Varga A, James D (2005) Detection and differentiation of Plum pox virus using real-time multiplex PCR with SYBR Green and melting curve analysis: a rapid method for strain typing. J Virol Methods 123:213–220

Walk ST, Alm EW, Calhoun LM, Mladonicky MJ, Whittam TS (2007) Genetic diversity and population structure of Escherichia coli isolated from freshwater beaches. Environ Microbiol 9:2274–2288

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed equally in the write up of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All sequences used in this study is available in the DNA Databank of Japan. See Additional file 1 for details. All other data are available on request.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies concerned with experiment on human or animals.

Funding

This work received funding from the Department of Science and Technology (DST)/the National Research Foundation (NRF)/South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI) in Water Quality and Wastewater management. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at are those of the authors and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional file

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekwanzala, M.D., Abia, A.L.K., Ubomba-Jaswa, E. et al. Genetic relatedness of faecal coliforms and enterococci bacteria isolated from water and sediments of the Apies River, Gauteng, South Africa. AMB Expr 7, 20 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-016-0319-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13568-016-0319-4