Abstract

Phage therapy holds promise as an alternative to antibiotics for combating multidrug-resistant bacteria. However, host bacteria can quickly produce progeny that are resistant to phage infection. In this study, we investigated the mechanisms of bacterial resistance to phage infection. We found that Rsm1, a mutant strain of Salmonella enteritidis (S. enteritidis) sm140, exhibited resistance to phage Psm140, which was originally capable of lysing its host at sm140. Whole genome sequencing analysis revealed a single nucleotide mutation at position 520 (C → T) in the rfbD gene of Rsm1, resulting in broken lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which is caused by the replacement of CAG coding glutamine with a stop codon TAG. The knockout of rfbD in the sm140ΔrfbD strain caused a subsequent loss of sensitivity toward phages. Furthermore, the reintroduction of rfbD in Rsm1 restored phage sensitivity. Moreover, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of rfbD in 25 resistant strains revealed a high percentage mutation rate of 64% within the rfbD locus. We assessed the fitness of four bacteria strains and found that the acquisition of phage resistance resulted in slower bacterial growth, faster sedimentation velocity, and increased environmental sensitivity (pH, temperature, and antibiotic sensitivity). In short, bacteria mutants lose some of their abilities while gaining resistance to phage infection, which may be a general survival strategy of bacteria against phages. This study is the first to report phage resistance caused by rfbD mutation, providing a new perspective for the research on phage therapy and drug-resistant mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salmonella enteritidis (S. enteritidis), a gram-negative bacterium belonging to the Family Enterobacteriaceae, exists widely in different natural environments [1, 2] and has more than 2600 serotypes globally that can cause foodborne salmonellosis [3, 4]. S. enteritidis is the most widespread serotype found in chicken meat and is a common cause of human illnesses [5]. Antibiotics are generally used to treat bacterial infections. However, the prolonged overuse of antibiotics has led to the widespread emergence of multidrug-resistant strains of S. enteritidis, which in turn poses a serious threat to human health [6,7,8,9,10]. Over the last two decades, the inadequate supply of new antibiotics has been unable to keep up with the relentless surge of bacterial resistance. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop new, efficient, and environmentally friendly antibacterial agents.

Bacteriophages (phages), which are estimated at 1031, approximately outnumbering bacteria by 100-fold, are the most abundant and diverse entities on Earth [11, 12]. Phages are widely distributed in the environment, occupying not only freshwater and marine habitats [13], surface soils [14, 15], and food sources, but also the gastrointestinal tracts of both humans and animals [16]. Phages have many advantages compared to antibiotics, antimicrobial peptides, and lysozymes. First, phages exhibit host specificity toward certain classes or species of bacteria. Second, they can be produced in large quantities and cheaply by reinfecting their bacterial hosts. Third, the phage genome demonstrates a certain degree of flexibility and can be modified through genetic engineering.

In recent years, a growing body of literature has documented the success of phage usage in the treatment of bacterial infection [17]. However, bacteria can use a range of defense strategies to fight phage infection. These strategies include modifying receptors to block phage adsorption, blocking the entry of phage DNA [18], degrading the phage genome through restriction-modification (RM) [19] and CRISPR-Cas systems [20], and preventing phage proliferation through abortive infection systems [21]. The phage receptors include various bacterial cell surface appendages, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), wall alginic acid, flagella, and certain, outer membrane proteins. Bacteria prevent phage adsorption and infection by shielding or blocking synthesis, or by transforming phage enzyme-mediated serotypes [22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. While this strategy effectively protects bacteria from phage infection, this comes at a cost to the bacteria, as the receptors involved, such as chemoreceptors, porins, and adhesins also play critical roles in bacterial metabolism and immune evasion [29].

In the process of making S. enteritidis resistant to phage infection, the bacterial regulation of LPS synthesis on its surface is a common resistance mechanism. The rfbD gene in S. enteritidis encodes dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose reductase, which plays a crucial role in the synthesis of bacterial LPS [30,31,32,33]. In Gram-negative bacteria, the rfb region houses the genes necessary for the production and assembly of sugars, forming the side-chain repeat units of the O-antigen [34,35,36,37,38]. O-antigens are located in the outermost layer of LPS, in the outer membrane of bacteria [39], and play a crucial role in bacterial immune response and pathogenicity. rfbD catalyses the reduction of dTDP-4-dehydrOβ-l-rhamnose to dTDP-β-l-rhamnose, thereby providing essential precursors for O-antigen and lipid A synthesis. Additionally, dTDP-rhamnose plays a crucial role in LPS synthesis, ultimately forming the repeating O-antigen structure. The genetic product encoded by rfbD facilitates the transfer of the O-antigen from the cytoplasmic membrane to the periplasmic side, resulting in complete LPS assembly [40,41,42].

In this study, we isolated a mutated strain of S. enteritidis, Rsm1, which exhibited resistance to phages. We conducted whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis to identify the specific genes responsible for facilitating this resistance. The sequencing results revealed that a single base substitution in rfbD caused structural damage in the LPS, which we believe is likely the cause of phage resistance in Rsm1. Our study showed for the first time that rfbD mutations facilitate bacterial resistance to phage infection.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and phages

Phage Psm140 and its host S. enteritidis sm140 were previously isolated from sewage and a chicken farm in Shandong Province, China, respectively, and are currently maintained in our laboratory. S. enteritidis sm140 belongs to the ST11 type, with a genome consisting of one chromosome (4 679 795 bp with a G + C content of 52.18%, GenBank: CP125220.1) and two plasmids (plasmid1: 64 327 bp with a G + C content of 51.76%, GenBank: CP125221.1; plasmid2: 29 336 bp with a G + C content of 47.22%, GenBank: CP125222.1). Psm140 (GenBank: PP437543) possesses a double-stranded linear DNA genome comprising 41 913 bp with a G + C content of 49.50% and belongs to the family Siphoviridae. Associated Professor Xiaoping Wu (College of Animal Science, Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University) provided the plasmids pCas (kanamycin-resistant) and pTarget (spectinomycin-resistant). Prof. Huoying Shi (College of Veterinary Medicine, Institute of Comparative Medicine, Yangzhou University) provided the plasmids pYA3334 (chloramphenicol-resistant) and pYA3334-Red (chloramphenicol-resistant).

Screening and identification of phage-resistant strains

A secondary infection experiment was conducted to screen for phage-resistant strains. Fifty μL of S. enteritidis sm140 was inoculated in 5 mL of a lysogeny broth (LB) liquid medium and cultured until it reached an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6. Phage Psm140 was then added to the culture at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1:1000 and cultured overnight. Following this, the culture was streaked out, and five distinct single colonies, designated as Rsm1 to Rsm5, were selected and purified across three successive rounds without the presence of phage Psm140. The double-layer agar plate method was applied to determine the development of resistance against phage Psm140. For the strains that did not exhibit any plaques, their specificity towards S. enteritidis was further confirmed using the Sdf I primer (Table 1), ensuring that there was no contamination from other microorganisms.

Genome sequencing of Rsm1

The genomic DNA of Rsm1 was extracted using the TIANamp Bacteria DNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) and then submitted to Personal Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for library construction and sequencing. The genomes of sm140 and Rsm1 were aligned using the BWA-MEM software [43], with default alignment parameters set for BWA-MEM.

The complete sequences of rfbD from sm140 and Rsm1 were separately amplified using the gene-specific primers rfbD F/R (Table 1). The amplified products were sent to TSINGKE Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China) for sequencing. The subsequent analysis was conducted using MegAlign software (DNASTAR v.10.0.1).

Validation of the phage receptor by CRISPR

The rfbD sequence was replicated on the CRISPOR prediction website for comprehensive analysis. A highly ranked sgRNA sequence (tgccgggggaaccacaacc) was meticulously selected. The 20 bp sgRNA fragment was then precisely cloned and inserted into the pTarget vector by PCR, using the sgRNA-CRISPR-F/R primers. Based on the sm140 genome sequence, the PCR primers AF/R and BF/R for rfbD were designed using the Primer Premier 5.0 software. Subsequently, the fused fragment AB was then skillfully generated by the process of overlapping PCR. Through the electroporation process, sm140 cells harboring the pCas plasmid and sm140-pCas cells harboring the pTarget-gRNA plasmid were obtained. Single clones were selected for PCR verification. The primers used in the procedures are listed in Table 1.

rfbD complementation

Homologous recombination primers 3334-rfbD F/R for rfbD and pYA3334 F/R for plasmid pYA3334 (Table 1) were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 software. The genome of sm140 and the plasmid pYA3334 were used as templates to PCR-amplify the respective 3334-rfbD and pYA3334 fragments, employing the aforementioned primer pairs. These PCR-generated fragments were subsequently purified and seamlessly recombined via a homologous recombinase to construct the recombinant plasmid, pYA3334-rfbD. They were then electroporated into Rsm1 recipient cells to enable normal expression of the rfbD protein. Phage Psm140 was employed to assess plaque formation in both the knockout strain sm140∆rfbD and the complemented strain Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD.

Determination of the adsorption capacity of phage Psm140

Bacteria strains (sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD) were cultured until reaching OD600 = 0.6. Subsequently, 200 μL of the bacterial suspension was mixed with 100 μL of a phage solution at a titer of 1 × 1010 PFU/mL (MOI = 100). 200 μL of fresh liquid LB medium was added to this mixture. As a control, 100 μL of phage solution was mixed with 400 μL of LB medium. The samples were then incubated at 37 °C for 7 min, followed by centrifugation at 12 000 ×g for 1 min to collect the supernatant containing the unabsorbed phages. The titer of the phages in the supernatant was an indicator of their non-adsorbed fraction. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. The bacterial pellet was resuspended in 1 × PBS and examined using TEM to determine phage-bacteria adsorption.

Morphological characterization of the bacteria

The sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD, and the Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD strains were individually inoculated into a liquid LB medium and cultured at 37 °C at 220 rpm until reaching an OD600 of 0.6. Subsequently, 3 μL of each culture was spotted onto solid LB agar plates and then air-dried. The plates were subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 72 h to observe the morphological differences between the bacteria strains. In addition, 10 μL of each bacteria suspension was dropped onto a copper grid and incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. An equal volume of negative staining solution containing 2% phosphotungstic acid (PTA) at pH = 7.0 was then added. The grids were air-dried. Finally, the dried grids were examined under a transmission electron microscope (TEM).

Determination of the structural integrity of bacterial LPS

The four strains were prepared as competent cells; 100 μL of each competent cell suspension was mixed with 100 ng of the pYA3334-red plasmid. Following electroporation, the cells were incubated in antibiotic-free LB medium that had been pre-warmed to 37 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 100 μL of the bacterial culture was plated on chloramphenicol-resistant solid LB agar. The expression of red fluorescent protein was visualized using a fluorescence microscope. Additionally, each bacterium strain containing pYA3334-Red was collected and centrifuged at 6000 × g for 5 min to discard the supernatant. The resulting bacterial pellets were resuspended in a solution containing 4% NaCl at 25 °C for 5 min.

The LPS of the four strains was also extracted by the hot phenol-water method [44], and SDS-PAGE was carried out, followed by silver staining.

Detection of the mutation rate of rfbD in phage-resistant strains

To determine the mutation rate of rfbD in phage-resistant strains, additional phage-resistant mutants were screened from double-layer plates containing phage (MOI = 10) using the method described by Habusha et al. [45]. Once the bacteria clones were visible to the naked eye, 25 of these clones were randomly selected for purification and cultivation. The phage spotting method was then used to verify their resistance to phage Psm140. The rfbD of the phage-resistant strains was amplified and sequenced, and its mutation rate was analysed. The mutation rates were calculated using the following formula: mutation rates = (total number of mutants/total number of strains) × 100%.

Determination of bacterial fitness before and after rfbD mutation

To compare the bacteria growth, nine tubes were set as follows: (1) 100 µL Rsm1 + 1.1 mL LB; (2) 100 µL Rsm1 + 1.0 mL LB + 100 µL Psm140; (3) 100 µL sm140∆rfbD + 1.1 mL LB; (4) 100 µL sm140∆rfbD + 1.0 mL LB + 100 µL Psm140; (5) 100 µL Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD + 1.1 mL LB; (6) 100 µL Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD + 1.0 mL LB + 100 µL Psm140; (7) 100 µL sm140 + 1.1 mL LB; (8) 100 µL sm140 + 1.0 mL LB + 100 µL Psm140; (9) 1.2 mL LB. All tubes were incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm for 12 h to determine OD600. Each experiment was replicated 3 times.

To test bacteria sedimentation, 60 µL of each strain was transferred to 6 mL of liquid LB medium and incubated for 12 h. Cultures were then allowed to settle at 25 °C for 48 h to observe bacterial sedimentation.

The pH of the LB medium was adjusted using either concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solutions to achieve values ranging from pH = 1.0 to pH = 12.0. The four strains were separately inoculated into a liquid LB medium and were incubated at 37 °C, 220 rpm for 12 h to determine the OD600. Each experiment was replicated 3 times.

For heat treatment, the four strains were individually exposed to temperatures ranging from 37 to 80 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, 100 μL of each bacterial suspension was serially diluted and spread evenly over LB agar plates. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 12 h, after which the number of bacterial colonies was counted. Each experiment was replicated 3 times.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing of the four bacterial strains was performed using the Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method in accordance with guidelines provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) [46] and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [47]. Bacterial suspensions were evenly spread on Mueller–Hinton agar (MHA) plates (AOBOX Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Beijing, China) and then incubated at 25 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, antibiotic discs (Hangzhou Microbial Reagent Co., Ltd. Hangzhou, China) were placed on the agar surface, and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16–18 h to observe the diameter of the inhibition zones. Detailed information about the antibiotics used can be found in Additional file 1.

Results

Screening and identification of phage-resistant strains

Phage resistance tests revealed that the positive control strain, sm140, was lysed by Psm140 (Figure 1A). Rsm1 exhibited resistance to Psm140 (Figure 1B). In contrast, strains Rsm2 to Rsm5 were still lysed by Psm140 (Figures 1C–F). Amplification of Rsm1, using the specific primer Sdf I for S. enteritidis, was followed by sequencing. Blast analysis confirmed that Rsm1 belonged to S. enteritidis and was not contaminated by other bacteria. Therefore, Rsm1 was selected for further experiments.

Comparative genomic analysis and identification of Rsm1 and sm140

Rsm1 sequencing generated a dataset comprising 1144 Mbp with 7,508,608 high-quality reads. These reads were aligned to the sm140 reference genome using BWA-MEM, achieving a mapping rate of 99.81%. An analysis of single nucleotide variations using GATK software identified a single homozygous SNP within the Rsm1 genome. The raw sequencing data have been deposited online in the SRA at the NCBI, under accession number SRP475041.

To validate the accuracy of the resequencing, PCR amplification of both the Rsm1 and sm140 rfbD was performed (Figure 2A), followed by sequencing alignment. This analysis confirmed a C to T mutation at position 520 of rfbD (Figure 2B), resulting in an amino acid substitution from glutamine to a stop codon at position 174 (Figure 2C). Consequently, the translation of rfbD was prematurely terminated. It was hypothesized that the abnormal expression of rfbD may underlie Rsm1’s tolerance to phages. To further investigate this hypothesis, we generated a rfbD knockout mutant for functional validation.

rfbD knockout and complementation

The rfbD knockout strain sm140∆rfbD was engineered using a combination of CRISPR and λ-Red technologies. The rfbD gene was successfully introduced into Rsm1 (Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD) by employing homologous recombination technology for complementation. For the phage Psm140 plaque assay, Sm140 was used as a positive control (Figure 3A). The results indicated that sm140∆rfbD could not produce plaques (Figure 3B), while Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD promoted plaque formation (Figure 3C). In summary, the rfbD knockout effectively rendered the bacteria resistant to phage-induced lysis.

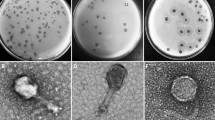

Adsorption rate of phage Psm140

The adsorption rates of phage Psm140 on sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD were 87.95, 28.22, 24.43, and 76.55%, respectively (Figure 4A). TEM revealed that the bacteria cell membrane of the wild-type strain sm140 was covered with dense phage particles (Figure 4B). In contrast, the naturally mutated Rsm1 developed resistance to phage Psm140, resulting in a significant decrease in adsorption (~59.73%), and very few phages were observed surrounding the bacteria cell, as shown in Figure 4C. These trends were also observed in the knockout strain sm140∆rfbD (Figure 4D). The construction of the complemented strain, Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD, resulted in the phage Psm140 adsorption rate returning to its natural level. This led to the appearance of a large number of phage particles on the bacterial surface (Figure 4E).

Results of the phage adsorption test. A Phage adsorption rate on bacteria. The variances among groups are delineated by comparative letter markers. Any two groups that exhibit no identical lowercase letters are considered significantly differences (P < 0.0001). B–E TEM images of sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD after co-incubation with the phage for 7 min.

Analysis of bacterial morphological structure

Both the sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD colonies exhibited white, rough-edged appearances, in contrast to the smooth and well-defined colonies of Rsm1 and sm140∆rfbD (Figure 5A). TEM analysis revealed that sm140 (Figure 5B), Rsm1 (Figure 5C), sm140∆rfbD (Figure 5D), and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD (Figure 5E) all retained their short ellipsoidal rod shapes, measuring approximately 1.5 μm by 0.8 μm, with no significant alterations observed. The surfaces of sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD were smooth, whereas the Rsm1 and sm140∆rfbD surfaces displayed wrinkling, accompanied by the presence of dark dye residues.

Determination of the integrity of bacterial LPS

The agglutination assay, a traditional method for evaluating the integrity of bacterial LPS, relies on the behavior of LPS in response to its core polysaccharide’s negative charge. In Gram-negative bacteria, this negative charge is exposed following the loss of side-chain polysaccharides on the LPS outer surface. In high-salt solutions, this, in turn, leads to aggregation. Conversely, bacteria with intact LPS structures do not aggregate and remain dispersed as individual entities, even in high-salt environments. To enhance visualization, we introduced a red fluorescent plasmid, pYA3334-red, into four strains using electroporation. The agglutination assays revealed that in a 4% NaCl solution, sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD predominantly remained individual entities, whereas Rsm1 showed partial aggregation, and sm140∆rfbD extensively formed aggregated patches. Subsequent silver staining experiments confirmed these findings, visibly indicating that the LPS structures of sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD were still intact. In contrast, the LPS structures of Rsm1 and sm140ΔrfbD were compromised, as demonstrated by their incomplete appearance, consistent with the aggregation observed in the agglutination assays (Figure 6).

Bacterial LPS integrity. A–D Microscopy images showing the dispersion of sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD, and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD bacteria after treatment with a 4% NaCl solution. Images were taken using a fluorescence microscope at 10 × 20 magnification. E Silver staining of LPS. Lane 1: protein Ladder (10 ~ 180 kDa); Lane 2: sm140; Lane 3: Rsm1; Lane 4: sm140∆rfbD; Lane 5: Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD.

Analysis of the mutation rate of rfbD in phage-resistant strains

After 24 h of co-cultivating the wild-type strain sm140 with phage Psm140 on a double-layer agar plate, 138 clones of various sizes grew on the plate. The 25 randomly selected colonies were purified 3 times and designated Rsm6-Rsm30. Verification was carried out using a phage Psm140 point-plate assay, which confirmed the resistance of Rsm6-Rsm30 against phage. The sm140 was used as a control in this study. Furthermore, the rfbD of Rsm6-Rsm30 was amplified and sequenced, and the sequencing data were subjected to comparative analysis (Additional file 2). Among the 25 resistant strains, 64% (16/25) exhibited base replacements and frameshift mutations in rfbD. The remaining 36% (9/25) of the resistant strains did not show any mutation in rfbD. Out of these 16 mutant strains, 11 exhibited frameshift mutations due to the deletion of the fifth base. This caused the premature termination of peptide chain elongation with a mutation at the 12th amino acid into a terminator codon. Other mutations observed included a G to A substitution at position 856 (one strain), a T to G substitution at position 880 (eight strains), and an A deletion at position 892 (three strains). These all led to subsequent changes within the amino acid sequence. Overall, these mutations were likely to affect the function and stability of rfbD, in turn affecting the synthesis and modification of LPS, as well as its phage adsorption ability. Based on the mutation rate of rfbD, it was speculated that in addition to mutations within rfbD, sm140 may possess other mechanisms for countering phage invasion, thereby enhancing its own survival capabilities. This diversity in resistance mechanisms could be an important strategy for the survival and proliferation of S. enteritidis within its natural environment.

Comparisons of bacterial fitness before and after rfbD mutation

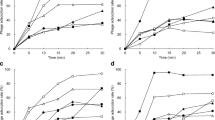

Considering that the mutation of rfbD conferred resistance to phage Psm140, we questioned whether this alteration affected the fitness of S. enteritidis. To investigate this matter further, we performed tests examining specific physiological characteristics of the bacteria, both before and after mutation. As shown in Figure 7A, the bacterial growth curve indicated that sm140’s growth significantly exceeded that of both Rsm1 and sm140ΔrfbD. Moreover, the growth pattern of Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD closely mirrors that of sm140, with no noteworthy differences observed. Following 12 h of co-culture with Psm140 phages, as shown in Figures 7B–E, it was observed that the growth of both Rsm1 and sm140ΔrfbD remained largely unaffected. In contrast, significant growth inhibition was experienced by both Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD and sm140.

Analysis of the physiological characteristics of the bacteria. A Growth of bacteria in the absence of phage. B–E Growth of Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD, Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD, and sm140 under co-cultivation conditions with phage Psm140. F Sedimentation results after 48 h of incubation at 25 °C for sm140, Rsm1, sm140∆rfbD, and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD (from left to right). G–H Sensitivity of bacteria to pH and temperature, respectively.

The sedimentation velocities were assessed after 48 h at 25 °C, as shown in Figure 7F. Both sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD exhibited slower sedimentation velocities, whereas Rsm1 and sm140ΔrfbD strains demonstrated faster sedimentation, possibly due to self-aggregation resulting in bacterial clumping.

The optimal pH for bacterial growth was altered following mutation (Figure 7G). The optimal pH for sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD was found to be in the range of 5.0–7.0, while for Rsm1 and sm140∆rfbD, it remained at pH 7.0. Moreover, the temperature sensitivity of the bacteria varied after mutation (Figure 7H). At 37 and 40 °C, the growth of all four strains remained largely unaffected. However, at 50 °C, the survival rates of sm140 and Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD were significantly higher than those of Rsm1 and sm140∆rfbD. At 60, 70, and 80 °C, the survival rates of all four bacterial strains were zero.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing revealed a significant increase in Rsm1 and sm140∆rfbD sensitivity to antibiotics, as detailed in Table 2. Among a total of 39 antibiotics, sm140 was resistant to 25, while Rsm1 and sm140ΔrfbD were resistant to only 14 and 13, respectively. These variations in drug resistance were primarily observed in antibiotics classified as β-lactams, nitrofurans, and quinolones. Following the complementation with rfbD, the resistance profile of Rsm1-pYA3334-rfbD was restored to the level of sm140. Detailed results from bacterial antibiotic susceptibility assays are provided in Additional file 1.

Discussion

The development of phage resistance in bacteria poses a significant challenge to the effective use of phages as natural antimicrobial agents within clinical settings. Consequently, it is imperative to undertake comprehensive research into the mechanisms that help bacteria acquire phage resistance. In this study, S. enteritidis Rsm1 exhibited stable resistance to phage Psm140 due to mutations in rfbD, which is involved in the synthesis of glycosyl units, the regulation of O-antigen formation, and the integrity of LPS function. In S. enteritidis, the rough phenotype is typically associated with the absence of the O-antigen, leading to an irregular or uneven surface appearance. This is due to the lack of polysaccharide chains on the bacterial surface. Some specific bacterial studies have previously documented this phenomenon [34, 41, 48,49,50]. The presence of residual staining at the periphery of the bacterial colonies can be attributed to PTA staining’s reaction with the O-antigen on their surface. Therefore, when strains lack rfbD by knockout, the amount of O-antigen on the bacterial surface is reduced or is missing. This hinders the binding between PTA and bacteria and causes a black dye circle to form. On the other hand, strains with mutant rfbD cannot synthesize the intact O-antigen, resulting in LPS defects [51,52,53]. Studies have demonstrated that deleting the O-antigen glycosyltransferase gene wadB in Brucella abortus leads to an incomplete LPS structure. This leads to reduced bacterial pathogenicity and increased antibiotic sensitivity [54]. Another study showed that in Pseudomonas extremaustralis, the deletion of the O-antigen glycosyltransferase gene wapH leads to increased permeability of the bacterial outer membrane, in turn decreasing its ability to adapt to external environments [55]. In addition, mutations in the waaC gene, which encodes the O-antigen synthase enzyme, can affect the synthesis of O-antigen and alter the bacteria surface’s structure, hindering phage recognition and infection [56]. Similarly, mutations in the genes rfaL and waaA, which both encode ribulose synthesis, can cause abnormalities in the LPS structure, affecting the infection process of phages [57, 58]. Mutations in RfaH gene, which encodes a transcriptional activator and regulates LPS synthesis, can interfere with the normal generation of LPS, also resulting in bacterial resistance to phages [59].

As an initial defense against phages, bacteria typically modify or remove receptors on their surface to prevent contact with the phage [60]. However, this alteration or deletion could be costly for the host, resulting in a decrease in bacteria growth and virulence [42, 61]. In this study, mutations in rfbD caused a defect in LPS, making the bacteria resistant to phages and affecting their bioactivity in other ways. Similar observations have been reported for other phage-resistant strains. For example, S. enteritidis Salp572ɸ1R has lost O-antigen-acquired resistance to phage ɸ1, but it is almost non-virulent in mice and shows suppressed expression of certain virulence-related genes such as cmE, sthE, and cheY [62]. In an in vivo experiment using a calf diarrhoea model, it was found that phage B41/1 reduced the virulence of Escherichia coli strains [63]. Deleting the key genes hmgA and galU in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA1 mutant strains resulted in the loss of O-antigen. This, in turn, led to phage resistance and reduced virulence [64]. These findings demonstrated that bacteria can develop resistance to phages by modifying or removing receptors on the surface of the bacteria. However, such changes often sacrifice bioactivity, indicating the trade-offs and challenges bacteria face regarding survival and reproduction. Achieving a balance between phage resistance and bacterial viability may be a survival strategy for bacteria. By studying the mutation principles of bacteriophage resistance, it is possible to develop universal bactericidal phage reagents for treating patients with clinical bacterial infection.

In this study, we confirmed that the resistance of Rsm1 to phage Psm140 stemmed from a point mutation in the Rsm1 genome, located at the 520 bp position in the rfbD gene (C → T transition). The consequent resistance of bacteria to phages, which also reduced their adaptive capabilities, was clearly demonstrated through targeted knockout experiments of rfbD, followed by complementation studies. This is the first report on a mutation in rfbD conferring phage resistance, and this finding provides a theoretical basis for studying phage therapy and resistance mechanisms in S. enteritidis infection.

Abbreviations

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharides

- PTA:

-

Phosphotungstic acid

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscope

- HCl:

-

Hydrochloric acid

- NaOH:

-

Sodium hydroxide

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- KDO:

-

3-Deoxy-D-manno-octulosonic acid

- WTAs:

-

Wall teichoic acids

References

Chiu LH, Chiu CH, Horn YM, Chiou CS, Lee CY, Yeh CM, Yu CY, Wu CP, Chang CC, Chu C (2010) Characterization of 13 multi-drug resistant Salmonella serovars from different broiler chickens associated with those of human isolates. BMC Microbiol 10:86

Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM (2011) Foodborne illness acquired in the United States–major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17:7–15

Guibourdenche M, Roggentin P, Mikoleit M, Fields PI, Bockemühl J, Grimont PA, Weill FX (2010) Supplement 2003–2007 (No. 47) to the White-Kauffmann-Le Minor scheme. Res Microbiol 161:26–29

Chen S, Zhao S, White DG, Schroeder CM, Lu R, Yang H, McDermott PF, Ayers S, Meng J (2004) Characterization of multiple-antimicrobial-resistant salmonella serovars isolated from retail meats. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:1–7

Thai TH, Hirai T, Lan NT, Yamaguchi R (2012) Antibiotic resistance profiles of Salmonella serovars isolated from retail pork and chicken meat in North Vietnam. Int J Food Microbiol 156:147–151

Butaye P, Michael GB, Schwarz S, Barrett TJ, Brisabois A, White DG (2006) The clonal spread of multidrug-resistant non-typhi Salmonella serotypes. Microbes Infect 8:1891–1897

Klontz KC, Klontz JC, Mody RK, Hoekstra RM (2010) Analysis of tomato and jalapeño and Serrano pepper imports into the United States from Mexico before and during a national outbreak of Salmonella serotype Saintpaul infections in 2008. J Food Prot 73:1967–1974

McGuinness S, McCabe E, O’Regan E, Dolan A, Duffy G, Burgess C, Fanning S, Barry T, O’Grady J (2009) Development and validation of a rapid real-time PCR based method for the specific detection of Salmonella on fresh meat. Meat Sci 83:555–562

Smith SI, Fowora MA, Goodluck HA, Nwaokorie FO, Aboaba OO, Opere B (2011) Molecular typing of Salmonella spp isolated from food handlers and animals in Nigeria. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2:73–77

Cabello FC (2006) Heavy use of prophylactic antibiotics in aquaculture: a growing problem for human and animal health and for the environment. Environ Microbiol 8:1137–1144

Brüssow H, Hendrix RW (2002) Phage genomics: small is beautiful. Cell 108:13–16

Fortier LC, Sekulovic O (2013) Importance of prophages to evolution and virulence of bacterial pathogens. Virulence 4:354–365

Srinivasiah S, Bhavsar J, Thapar K, Liles M, Schoenfeld T, Wommack KE (2008) Phages across the biosphere: contrasts of viruses in soil and aquatic environments. Res Microbiol 159:349–357

Williamson KE, Radosevich M, Wommack KE (2005) Abundance and diversity of viruses in six Delaware soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:3119–3125

Prigent M, Leroy M, Confalonieri F, Dutertre M, DuBow MS (2005) A diversity of bacteriophage forms and genomes can be isolated from the surface sands of the Sahara Desert. Extremophiles 9:289–296

Shkoporov AN, Hill C (2019) Bacteriophages of the human gut: the “known unknown” of the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 25:195–209

Li GM (2008) Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res 18:85–98

Kintz E, Davies MR, Hammarlöf DL, Canals R, Hinton JC, van der Woude MW (2015) A BTP1 prophage gene present in invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella determines composition and length of the O-antigen of the lipopolysaccharide. Mol Microbiol 96:263–275

Sneppen K, Semsey S, Seshasayee AS, Krishna S (2015) Restriction modification systems as engines of diversity. Front Microbiol 6:528

Al-Shayeb B, Sachdeva R, Chen LX, Ward F, Munk P, Devoto A, Castelle CJ, Olm MR, Bouma-Gregson K, Amano Y, He C, Méheust R, Brooks B, Thomas A, Lavy A, Matheus-Carnevali P, Sun C, Goltsman DSA, Borton MA, Sharrar A, Jaffe AL, Nelson TC, Kantor R, Keren R, Lane KR, Farag IF, Lei S, Finstad K, Amundson R, Anantharaman K, Zhou J, Probst AJ, Power ME, Tringe SG, Li WJ, Wrighton K, Harrison S, Morowitz M, Relman DA, Doudna JA, Lehours AC, Warren L, Cate JHD, Santini JM, Banfield JF (2020) Clades of huge phages from across Earth’s ecosystems. Nature 578:425–431

Sekulovic O, Ospina Bedoya M, Fivian-Hughes AS, Fairweather NF, Fortier LC (2015) The Clostridium difficile cell wall protein CwpV confers phase-variable phage resistance. Mol Microbiol 98:329–342

Allison GE, Verma NK (2000) Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol 8:17–23

Scholl D, Adhya S, Merril C (2005) Escherichia coli K1’s capsule is a barrier to bacteriophage T7. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4872–4874

Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Maerkedahl RB, Svenningsen SL (2013) A quorum-sensing-induced bacteriophage defense mechanism. mBio 4:e00362-e412

Manning AJ, Kuehn MJ (2011) Contribution of bacterial outer membrane vesicles to innate bacterial defense. BMC Microbiol 11:258

Hoque MM, Naser IB, Bari SM, Zhu J, Mekalanos JJ, Faruque SM (2016) Quorum regulated resistance of Vibrio cholerae against environmental bacteriophages. Sci Rep 6:37956

Høyland-Kroghsbo NM, Paczkowski J, Mukherjee S, Broniewski J, Westra E, Bondy-Denomy J, Bassler BL (2017) Quorum sensing controls the Pseudomonas aeruginosa CRISPR-Cas adaptive immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:131–135

Bondy-Denomy J, Qian J, Westra ER, Buckling A, Guttman DS, Davidson AR, Maxwell KL (2016) Prophages mediate defense against phage infection through diverse mechanisms. ISME J 10:2854–2866

Hyman P, Abedon ST (2010) Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv Appl Microbiol 70:217–248

Dong C, Beis K, Giraud MF, Blankenfeldt W, Allard S, Major LL, Kerr ID, Whitfield C, Naismith JH (2003) A structural perspective on the enzymes that convert dTDP-d-glucose into dTDP-l-rhamnose. Biochem Soc Trans 31:532–536

Giraud MF, Naismith JH (2000) The rhamnose pathway. Curr Opin Struct Biol 10:687–696

Law A, Stergioulis A, Halavaty AS, Minasov G, Anderson WF, Kuhn ML (2017) Structure of the Bacillus anthracis dTDP-L-rhamnose-biosynthetic enzyme dTDP-4-dehydrorhamnose reductase (RfbD). Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 73:644–650

Vinh T, Adler B, Faine S (1986) Ultrastructure and chemical composition of lipopolysaccharide extracted from Leptospira interrogans serovar copenhageni. J Gen Microbiol 132:103–109

Xiang SH, Haase AM, Reeves PR (1993) Variation of the rfb gene clusters in Salmonella enterica. J Bacteriol 175:4877–4884

Macpherson DF, Manning PA, Morona R (1994) Characterization of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthetic genes encoded in the rfb locus of Shigella flexneri. Mol Microbiol 11:281–292

Formal SB, Gemski P, Baron LS, Labrec EH (1970) Genetic transfer of Shigella flexneri antigens to Escherichia coli K-12. Infect Immun 1:279–287

Petrovskaya VG, Licheva TA (1982) A provisional chromosome map of Shigella and the regions related to pathogenicity. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung 29:41–53

Whitfield C, Roberts IS (1999) Structure, assembly and regulation of expression of capsules in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 31:1307–1319

Kim M, Kim S, Park B, Ryu S (2014) Core lipopolysaccharide-specific phage SSU5 as an auxiliary component of a phage cocktail for Salmonella biocontrol. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1026–1034

Lalsiamthara J, Kaur G, Gogia N, Ali SA, Goswami TK, Chaudhuri P (2020) Brucella abortus S19 rfbD mutant is highly attenuated, DIVA enable and confers protection against virulent challenge in mice. Biologicals 63:62–67

Mitchison M, Bulach DM, Vinh T, Rajakumar K, Faine S, Adler B (1997) Identification and characterization of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis and transfer genes of the lipopolysaccharide-related rfb locus in Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. J Bacteriol 179:1262–1267

Zhou Y, Xiong D, Guo Y, Liu Y, Kang X, Song H, Jiao X, Pan Z (2023) Salmonella Enteritidis RfbD enhances bacterial colonization and virulence through inhibiting autophagy. Microbiol Res 270:127338

Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25:1754–1760

Conrad RS, Galanos C (1989) Fatty acid alterations and polymyxin B binding by lipopolysaccharides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa adapted to polymyxin B resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:1724–1728

Habusha M, Tzipilevich E, Fiyaksel O, Ben-Yehuda S (2019) A mutant bacteriophage evolved to infect resistant bacteria gained a broader host range. Mol Microbiol 111:1463–1475

Guzman M, Dille J, Godet S (2012) Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Nanomedicine 8:37–45

Khoshbakht R, Salimi A, Shirzad Aski H, Keshavarzi H (2013) Antibiotic susceptibility of bacterial strains isolated from urinary tract infections in Karaj, Iran. Jundishapur J Microbiol 6:86–90

Gao M, D’Haeze W, De Rycke R, Wolucka B, Holsters M (2001) Knockout of an azorhizobial dTDP-L-rhamnose synthase affects lipopolysaccharide and extracellular polysaccharide production and disables symbiosis with Sesbania rostrata. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 14:857–866

Jayeola V, McClelland M, Porwollik S, Chu W, Farber J, Kathariou S (2020) Identification of novel genes mediating survival of Salmonella on low-moisture foods via transposon sequencing analysis. Front Microbiol 11:726

Robertson BD, Frosch M, van Putten JP (1994) The identification of cryptic rhamnose biosynthesis genes in Neisseria gonorrhoeae and their relationship to lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 176:6915–6920

Whitfield C (2006) Biosynthesis and assembly of capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. Annu Rev Biochem 75:39–68

Raetz CR, Whitfield C (2002) Lipopolysaccharide endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem 71:635–700

Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA (2010) c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science 328:1703–1705

Arce G, Iriarte H, Zuniga R, Gil R (2014) The identification of wadB, a new glycosyltransferase gene, confirms the branched structure and the role in virulence of the lipopolysaccharide core of Brucella abortus. Microb Pathog 73:53–59

Benforte FC, Colonnella MA, Ricardi MM, Solar VEC, Leonardo L, López Nancy I, Tribelli PM, Appanna VD (2018) Novel role of the LPS core glycosyltransferase WapH for cold adaptation in the Antarctic bacterium Pseudomonas extremaustralis. PLoS One 13:e0192559

Valvano MA, Messner P, Kosma P (2002) Novel pathways for biosynthesis of nucleotide-activated glycero-manno-heptose precursors of bacterial glycoproteins and cell surface polysaccharides. Microbiology 148:1979–1989

Kneidinger B, Marolda C, Graninger M, Zamyatina A, McArthur F, Kosma P, Valvano MA, Messner P (2002) Biosynthesis pathway of ADP-L-glycero-beta-D-manno-heptose in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 184:363–369

Donohue-Rolfe A, Kondova I, Oswald S, Hutto D, Tzipori S (2000) Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains that express Shiga toxin (Stx) 2 alone are more neurotropic for gnotobiotic piglets than are isotypes producing only Stx1 or both Stx1 and Stx2. J Infect Dis 181:1825–1829

Murray GL, Attridge SR, Morona R (2003) Regulation of Salmonella typhimurium lipopolysaccharide O antigen chain length is required for virulence; identification of FepE as a second Wzz. Mol Microbiol 47:1395–1406

Labrie SJ, Samson JE, Moineau S (2010) Bacteriophage resistance mechanisms. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:317–827

Capparelli R, Nocerino N, Lanzetta R, Silipo A, Amoresano A, Giangrande C, Becker K, Blaiotta G, Evidente A, Cimmino A, Iannaccone M, Parlato M, Medaglia C, Roperto S, Roperto F, Ramunno L, Iannelli D (2010) Bacteriophage-resistant Staphylococcus aureus mutant confers broad immunity against staphylococcal infection in mice. PLoS One 5:e11720

Capparelli R, Nocerino N, Iannaccone M, Ercolini D, Parlato M, Chiara M, Iannelli D (2010) Bacteriophage therapy of Salmonella enterica: a fresh appraisal of bacteriophage therapy. J Infect Dis 201:52–61

Smith HW, Huggins MB, Shaw KM (1987) The control of experimental Escherichia coli diarrhoea in calves by means of bacteriophages. J Gen Microbiol 133:1111–1126

Le S, Yao X, Lu S, Tan Y, Rao X, Li M, Jin X, Wang J, Zhao Y, Wu NC, Lux R, He X, Shi W, Hu F (2014) Chromosomal DNA deletion confers phage resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci Rep 4:4738

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Professor Xiaoping Wu (Fujian Agricultural and Forestry University) and Professor Huoying Shi (Yangzhou University) for generously providing the pCas, pTarget, and pYA3334 plasmid materials used in this study.

Funding

This study received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No: 32271435) and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XZ and YL, supervised the project, conceived the experiments, and revised the manuscript. YZ performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript draft. PL, SL and MS, participated in part of the experimental data collection and discussion. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Handling editor: Marcelo Gottschalk.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Drug susceptibility test results for the strains.

Additional file 2

: Sequence alignment analysis of rfbD in phage-resistant strains.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Li, P., Liu, S. et al. Salmonella enteritidis acquires phage resistance through a point mutation in rfbD but loses some of its environmental adaptability. Vet Res 55, 85 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-024-01341-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-024-01341-7