Abstract

Senegalese sole is susceptible to marine VHSV isolates but is not affected by freshwater isolates, which may indicate differences regarding virus-host immune system interaction. IFN I induces an antiviral state in fish, stimulating the expression of genes encoding antiviral proteins (ISG). In this study, the stimulation of the Senegalese sole IFN I by VHSV infections has been evaluated by the relative quantification of the transcription of several ISG (Mx, Isg15 and Pkr) after inoculation with marine (pathogenic) and freshwater (non-pathogenic) VHSV isolates. Compared to marine VHSV, lower levels of RNA of the freshwater VHSV induced transcription of ISG to similar levels, with the Isg15 showing the highest fold induction. The protective role of the IFN I system was evaluated in poly I:C-inoculated animals subsequently challenged with VHSV isolates. The cumulative mortality caused by the marine isolate in the control group was 68%, whereas in the poly I:C-stimulated group was 5%. The freshwater VHSV isolate did not cause any mortality. Furthermore, viral RNA fold change and viral titers were lower in animals from the poly I:C + VHSV groups than in the controls. The implication of the IFN I system in the protection observed was confirmed by the transcription of the ISG in animals from the poly I:C + VHSV groups. However, the marine VHSV isolate exerts a negative effect on the ISG transcription at 3 and 6 h post-inoculation (hpi), which is not observed for the freshwater isolate. This difference might be partly responsible for the virulence shown by the marine isolate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The type I interferon (IFN I) promotes an antiviral state by inducing the transcription of numerous interferon stimulated genes (ISG), such as Mx, interferon-stimulated gene 15 (Isg15), and the protein kinase R (Pkr) genes [1], which will be considered as markers of the Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) IFN I activity in this study.

Mx proteins are large GTPases involved in intracellular membrane remodelling and intracellular trafficking [2]. In teleosts, the expression of these proteins in response to polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (poly I:C) or viral infection, as well as their virus-specific antiviral activity, have been widely demonstrated [1, 3, 4]. The antiviral activity of these proteins depends on the interaction between the Mx protein and specific viral target proteins, inhibiting the viral genome synthesis or the viral particle assembly [3, 5].

ISG15 are ubiquitin-like proteins containing two tandem repeats of ubiquitin-like domains. In mammals, these proteins can conjugate to either, cellular or viral target proteins, via the C-terminal LRLRGG sequence (ISGylation), which is controlled by a series of IFN-inducible enzymes [6, 7]. However, unlike ubiquitin, ISGylated proteins are not degraded in the proteasome [8]. In addition to their antiviral activity, ISG15 proteins seem to be involved in regulating the IFN I signalling [9, 10]. In teleosts, Isg15 gene transcription has been studied in different species [11–15], determining that fish ISG15 proteins contain the critical C-terminal glycine residues, which suggests that they could conjugate to target proteins and have antiviral activity similar to their mammalian counterparts. In fact, the ISG15 antiviral activity has been demonstrated in several fish species [12, 14].

PKR proteins are involved in many cellular processes, including cell proliferation and cell growth, apoptosis, and tumor suppression. In mammals, PKR is activated by phosphorylation triggered by double-stranded RNA (dsRNA). Once activated, PKR phosphorylates the eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (elF-2α), causing the inhibition of protein synthesis [16]. Pkr genes have been studied in diverse fish species to date [17–22], and their transcription after poly I:C inoculation has been reported in rock bream (Oplegnatus fasciatus) spleen and fugu (Takifugu rubripes) leucocytes [20, 21]. However, the antiviral mechanism of fish PKR has only been described in Japanese flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) embryonic cells, in which the over-expression of Pkr increases elF-2α phosphorylation [19].

Viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia Virus (VHSV) is the causal agent of the viral haemorrhagic septicaemia (VHS), an important disease affecting farmed salmonid species. However, the occurrence of VHSV in wild marine fish has led to the conclusion that the virus is enzootic in the marine environment and endemic in northern European waters [23]. The existence of genetic links among VHSV isolates recovered from wild fish and isolates responsible for epizootics in farmed turbot has been demonstrated [24]. Furthermore, VHSV has been recently detected in wild fish caught in southern European coastal waters [25]. Therefore, the existence of this marine VHSV reservoir may represent a potential risk for farmed Senegalese sole, which has been demonstrated to be susceptible to VHSV by experimental infection [26].

In Senegalese sole, the IFN I system has only been studied after poly I:C treatment or the inoculation with the Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis Virus (IPNV), showing antiviral activity against this viral infection [27]. In addition, the only ISG characterized in this fish species to date is Mx. Thus, the Senegalese sole Mx protein (SsMx) shows in vitro antiviral activity against VHSV [28], and this virus activates the SsMx promoter in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) gonad (RTG-2) cells [29]; however, there is no information about the in vivo response of the Senegalese sole IFN I system to VHSV infections.

In this study, the activity of the IFN I system of juvenile Senegalese sole has been evaluated by measuring the transcription of Mx, Isg15 and Pkr, as markers of the IFN I activation, in response to poly I:C and infections with VHSV isolates pathogenic and non-pathogenic to sole. Additionally, the protection conferred by the IFN I system against both VHSV infections has been tested by the stimulation with poly I:C prior to VHSV inoculations.

Materials and methods

Viruses and cell culture conditions

Two VHSV isolates were used: (1) VHSV genotype III (SpSm-IAusc2897, marine isolate obtained from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus), pathogenic (P) to Senegalese sole) [26, 30], and (2) VHSV genotype I (DK-F1), reference strain [31, 32] (freshwater isolate obtained from rainbow trout, non-pathogenic (NP) to Senegalese sole) kindly provided by Dr. Olesen (National Veterinary Institute, Arhus, Denmark). Viruses were propagated on the epithelioma papolosum cyprini (EPC) cell line. EPC cells were grown on 75-cm2 flasks (Nunc) at 25 °C in Leibovitz’s medium (L15, Lonza) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS, Lonza), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Lonza) until semiconfluence prior to virus inoculation. Inoculated EPC cells were maintained in L15 medium with 2% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin at 15 °C, and they were monitored until cytopathic effect (CPE) emergence. Supernatants were then collected, centrifuged at 5000×g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the resulting viral suspensions were titrated by the endpoint dilution method on 96-well plates. The 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was estimated by the method of Reed and Muench [33]. Both virus isolates were stored at −80 °C until use.

Fish challenges

Juvenile Senegalese sole specimens (between 9.5 and 11.5 g) were acclimatized for 15 days at the facilities of the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). Fish used in this study were treated according to the Spanish directive (RD 53/2013, BOE no. 34). Fish were maintained in 125-L aquaria with aeration under stable temperature (16 °C ± 0.5) and salinity (36–37 g/L) conditions. Prior to challenge, 10 fish were analyzed by PCR in order to discard previous infections with IPNV, VHSV or the Nervous Necrosis Virus (NNV) according to the methodology previously described [34–37]. All tests were negative (data not shown).

For the analysis of the Mx, Isg15 and Pkr transcription in response to VHSV infections, Senegalese sole specimens were distributed in four groups (n = 18 per group, Figure 1A): (1–2) virus-inoculated groups (inoculated with the freshwater (NP) or marine (P) VHSV isolate, 104 TCID50/fish), (3) negative control group (inoculated with L15), (4) positive control group (inoculated with poly I:C, 15 mg/Kg in L15). All the inoculations were performed by intraperitoneal injection (IP) in 0.1 mL (final volume).

Experimental design. A Induction of ISG transcription by VHSV isolates pathogenic (P) or non-pathogenic (NP) to sole. L15 and poly I:C-inoculated fish were negative and positive controls, respectively. B Induction of an antiviral state by poly I:C. First injection was with L15 or poly I:C. Second injection (24 h after first inoculation) was with L15 (negative control) or pathogenic or non-pathogenic VHSV isolates. Cumulative mortality was determined. In both challenges, ISG transcription was quantified and viral multiplication was also evaluated by viral genome quantification and viral titration.

Three animals per group were sacrificed by anaesthetic overdose (MS-222, Sigma) at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72 hpi. Head kidney, and pooled spleen and heart were aseptically collected and individually processed as indicated below. Head kidney samples were stored at −80 °C in RNA later solution (Ambion) until RNA extraction. Pooled spleen-heart samples were stored at −20 °C until virus quantification.

The putative protection conferred by the IFN I system elicited by poly I:C against the marine and freshwater VHSV isolates was also evaluated. To fulfil this objective, the following six groups (n = 43 per group) were considered: (1) L15 + L15 group (first and second inoculation with L15), (2) poly I:C + L15 group (first inoculation with poly I:C, second inoculation with L15), (3–4) L15 + VHSV groups (first inoculation with L15, second inoculation with the VHSV isolates), (5–6) poly I:C + VHSV groups (first inoculation with poly I:C, second inoculation with the VHSV isolates) (Figure 1B). All the inoculations were performed by IP injection (0.1 mL, final volume). Second inoculation was always 24 h after the first inoculation. Poly I:C concentration was 15 mg/Kg. The viral inoculum was 2 × 105 TCID50/fish.

Head kidneys were collected from fish at 3, 6, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h after second injection. Pooled spleen-heart were sampled at 1, 2 and 3 days post-2nd inoculation. Three animals were sacrificed per group, and samples were individually processed. Spare fish (n = 25) were maintained for 30 days in order to record the cumulative mortality. Dead fish were processed to calculate the viral titer.

Tissue processing for viral titration

Pooled spleen-heart from sampled and dead fish, were homogenized (10% w/v) in Earle’s medium (Hyclone) supplemented with 0.1 mg/mL gentamicin (Lonza), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin. Homogenates were centrifuged at 600×g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were collected and incubated for 12 h at 4 °C. Treated supernatants were stored at −80 °C until titration on EPC cells by the TCID50 method. Sample viral titers were calculated in triplicate and data were log-transformed. Mean values were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis

For RNA isolation, organs in RNA later were thawed, and the tissues were homogenized (10% w/v) in L15 supplemented with 2% FBS, 100 IU/mL penicillin and 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin, using the T10 basic Ultra-Turrax (IKA). Total RNA isolation was carried out on 250 μL of tissue homogenate using the TRI Reagent (Sigma), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Final RNA concentration was measured at 260 nm with the nanodrop system (ND-1000), and RNA quality was checked by electrophoresis. RNA was stored at −80 °C until use.

Total RNA was treated with DNase (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was accomplished using 500 ng of RNA, the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and random hexamer primers in a 20-μL reaction mix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA concentration was determined at 260 nm with the nanodrop system. cDNA was stored at −20 °C until use.

Quantification of ISG transcription and viral RNA

The transcription of the Mx, Isg15, and Pkr genes, as well as the relative fold change values of the viral nucleoprotein (N) RNA, were quantified by SYBR Green real-time PCR protocols using specific primers (Table 1). The specificity of these primers was determined by melting curve analyses and sequencing of each amplified product (Genetic Analyzer ABI PRIMS 3130, Applied Biosystems) (data non-shown). The ubiquitin (Ubq) and the ribosomal protein S4 (Rps4) were used as housekeeping genes (Table 1).

All real-time PCR reactions were performed in 20-μL mixtures containing 10 μL of 2 × Fast essential-SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Roche), 1 μL of each primer (0.75 μM, final concentration), and cDNA (100 ng). The amplification profile was 5 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, 20 s at 60 °C and 15 s at 72 °C. Fluorescence was measured at 60 °C in each cycle. Samples were run in triplicate with non-template controls on the same plate. Reactions were conducted with the LightCycler 480 II (Roche) system in 96-well plates, and data were analyzed with the LightCycler 480 software version 1.5.1. Relative cDNA levels were calculated by the 2−∆∆CT method and expressed as relative fold change respect to a calibrator group, the negative control group (L15) [38, 39]. According to Livak and Schmittgen [38], mean relative fold change values ±SD <2 were considered as non-detected (ND). Relative data were log-transformed for statistical analysis. Mean values were statistically analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Bonferroni test. Differences were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

ISG transcription and viral genome quantification after VHSV infection

The relative transcription of Mx, Isg15 and Pkr, as well as the viral genome, were quantified and comparatively analyzed after the inoculation of two different VHSV isolates, a marine isolate, pathogenic to Senegalese sole, and a freshwater isolate, non-pathogenic to this fish species. Poly I:C-inoculated animals were used as the positive control.

As shown in Figure 2A–C, poly I:C induces the transcription of Mx and Isg15 (both from 3 to 72 hpi), as well as Pkr (at 12 and 24 hpi). The highest fold induction was recorded for the Isg15 gene at 12 and 24 hpi (699 and 357 mean relative fold change values, respectively).

Relative fold change of ISG transcription (A–C) and viral RNA (D) by RT-qPCR. The study was conducted in head kidney from animals inoculated with VHSV isolates pathogenic (P) and non-pathogenic (NP) to sole. Poly I:C-inoculated animals were used as positive control. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three different samples. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups at each sampling time and within the same group throughout the time. ND: Non-detected relative fold change with respect to the negative control group (L15, not represented in the graphic).

Both VHSV isolates also induced the transcription of the three ISG (Figure 2A–C). The P VHSV isolate induced Mx and Isg15 transcription from 24 hpi onwards (Figure 2A, B), and Pkr transcription at 48 and 72 hpi (Figure 2C). The NP VHSV isolate stimulated Mx, Isg15 and Pkr transcription at 48 and 72 hpi at the same level as the P VHSV (Figure 2A–C).

In order to examine viral replication, the viral nucleoprotein gene was quantified at different times post-inoculation (pi). As shown in Figure 2D, the P VHSV isolate displayed an earlier genome replication (at 24 hpi), compared to the NP VHSV (at 48 hpi). Thus, the level of viral RNA at 24 and 48 hpi was lower in animals inoculated with the NP VHSV isolate (2.33 and 59.82 mean relative fold change values, respectively) than in fish injected with the P VHSV (64.7 and 1688 mean relative fold change values, respectively); however, similar viral RNA levels were recorded for both isolates at 72 hpi.

The NP VHSV titers in pooled spleen and heart samples were stable from 3 to 72 hpi (ca. 104 TCID50/g). The P VHSV titers were similar to those obtained with the NP VHSV from 3 to 48 hpi but increased at 72 hpi, displaying viral titers tenfold higher at the same time pi.

Effect of the IFN I system stimulated by poly I:C on VHSV infection

In order to study the role of the IFN I system against VHSV infection, fish were inoculated with poly I:C and subsequently challenged with the marine or freshwater VHSV isolates (Figure 1B).

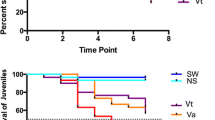

A drastic reduction of the mortality caused by the marine isolate was recorded in fish previously injected with poly I:C (poly I:C + P VHSV group, 5%) compared to mortality in non-stimulated animals (L15 + P VHSV group, 68%) (Figure 3). In this group, mortality onset was at 6 days post-inoculation (dpi), reaching the maximum value at 9 dpi. Mortality was stabilized at 16–17 dpi. Fish inoculated with the NP VHSV isolate (L15 + NP VHSV group) did not show any mortality (Figure 3). Infective viral particles were isolated from dead fish.

The stimulation of the IFN I system elicited by poly I:C resulted in an important decrease in the viral RNA fold change for both VHSV isolates at all sampling times (Figures 4D, 5D). Specifically, in fish infected with the P VHSV (L15 + P VHSV group) (Figure 4D) viral replication began at 12 hpi, although viral genome was detected from 3 hpi onwards, reaching the maximum mean value (30 000 relative fold change) at 48 hpi, and decreasing at 72 hpi. In poly I:C-stimulated fish inoculated with this isolate (poly I:C + P VHSV group), viral RNA fold change was 6200 fold lower than those recorded in non-stimulated animals at 48 hpi, when the maximum mean relative fold change value was recorded (Figure 4D). Regarding the NP VHSV replication (Figure 5D), in control fish (L15 + NP VHSV group) viral genome was detected at 12 hpi, and the maximum mean relative fold change (ca. 1000) was at 48 and 72 hpi. However, in poly I:C-stimulated animals (poly I:C + NP VHSV group) viral replication was not detected at any time tested (Figure 5D).

Interaction between the IFN I system and the infection with the pathogenic (P) VHSV isolate. The quantification of ISG transcription (A–C) and viral RNA (D) were evaluated in head kidney from poly I:C-stimulated and non-stimulated animals inoculated with the P VHSV isolate, and expressed as relative fold change with respect to the negative control group (L15 + L15). Poly I:C-inoculated animals were used as the positive control. Second inoculation was 24 h after the first inoculation. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three different samples. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups at each sampling time and within the same group throughout the time. ND: Non-detected relative fold change with respect to the negative control group (L15 + L15, not represented in the graphic).

Interaction between the IFN I system and the infection with the non-pathogenic (NP) VHSV isolate. The quantification of ISG transcription (A–C) and viral RNA (D) were evaluated in head kidney from poly I:C-stimulated and non-stimulated animals inoculated with the NP VHSV isolate, and expressed as relative fold change with respect to the negative control group (L15 + L15). Poly I:C-inoculated animals were used as the positive control. Second inoculation was 24 h after the first inoculation. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three different samples. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups at each sampling time and within the same group throughout the time. ND Non-detected relative fold change respect to the negative control group (L15 + L15, not represented in the graphic).

Infective viral particles were quantified in spleen-heart samples from infected animals (Figure 6). The P VHSV titers in stimulated fish (poly I:C + P VHSV group) remained stable throughout the time (ca. 105 TCID50/g), whereas in control fish (L15 + P VHSV group) a significant increase (tenfold) in the viral titer was recorded at 3 days. Regarding the NP VHSV, in stimulated fish (poly I:C + NP VHSV group) titers were similar at all times tested (ca. 103 TCID50/g), whilst in control fish (L15 + NP VHSV group) a significant increase was detected at 2 and 3 dpi (10 and 50 fold, respectively) over the average titer at 1 dpi (Figure 6).

Viral titer (log 10 TCID 50 /g) in pooled spleen-heart of sampled animals from the L15 + VHSV and poly I:C + VHSV groups. (P) animals inoculated with the pathogenic VHSV isolate. (NP) animals inoculated with the non-pathogenic VHSV isolate. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation (SD) obtained from three different samples. Different letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) between groups at each sampling times and within the same group throughout the time.

The highest viral titers (2 × 106 TCID50/g) were recorded from fish dead at 9 and 16 dpi (data non-shown).

Effect of VHSV infection on the IFN I response triggered by poly I:C

The transcription of Mx, Isg15 and Pkr was quantified in head kidney from animals injected with poly I:C and subsequently challenged with the pathogenic (Figure 4A–C) and the non-pathogenic VHSV isolates (Figure 5A–C).

In the challenge conducted with the P VHSV isolate, the fold induction of the three genes in poly I:C-stimulated animals (poly I:C + P VHSV group) was significantly lower than those recorded in the poly I:C + L15 group, mainly at 3 h post-2nd injection, for Mx and Isg15, and at 3 and 6 h post-2nd injection, for Pkr. However, from 12 h post viral infection onward, relative fold change values were similar in both groups or even higher in infected animals (poly I:C + P VHSV group) than in the poly I:C + L15 group (Figure 4A–C).

Regarding the NP isolate, the ISG transcription in infected and non-infected poly I:C-stimulated fish was similar at all times tested (Figure 5). As shown in Figure 5A–C, NP VHSV (L15 + NP VHSV) induces the transcription of the Mx and Isg15 genes from 48 hpi and Pkr gene from 24 hpi. The Isg15 and Mx genes showed the highest fold induction, with the maximum mean values at 72 hpi (ca. 1000 relative fold change values).

Discussion

ISG have been classically used as indicators of the IFN I system activation by viral infections or chemical inducers, such as poly I:C. In this study, the transcription of different ISG (Mx, Isg15 and Pkr) has been quantified in Senegalese sole after the inoculation with poly I:C or VHSV isolates with different levels of virulence, a marine isolate, pathogenic to sole under experimental conditions [26], and a freshwater isolate, which replicates in sole, although it does not cause mortality in this fish species (current study, Figure 3). This is the first report of Isg15 and Pkr transcriptional induction in Senegalese sole, whereas high levels of Mx mRNA had been previously reported after poly I:C inoculation in this species [27].

Poly I:C inoculation resulted in the transcription of the three ISG under study, with the Isg15 gene showing the earliest (at 3 hpi) and highest transcriptional levels, which is in concordance with previous studies. In particular, an early Isg15 transcription has been reported in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua), Japanese flounder, as well as in several fish cell lines [13, 14]. In addition, high levels of Isg15 transcription have been recorded in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and turbot [12, 15]. The Mx transcription was tenfold lower than the transcription recorded for the Isg15 gene, although Mx transcriptional levels were similar to those recorded in other fish species such as channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus), rainbow trout, Atlantic salmon, rock bream, gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and carp (Cyprinus carpio) [40–45]. Pkr transcription was 100-fold lower than Isg15 transcription. This low transcriptional level has also been described in rock bream and fugu kidney and spleen [20, 21], and could be associated with the mechanism of PKR action, as this protein inhibits the protein synthesis, and, therefore, high levels of PKR could compromise cellular viability.

In general terms, VHSV is a strong inducer of the IFN system, stimulating the transcription of the three ISG later than poly I:C, as it was previously reported for Mx transcription after IPNV inoculation in Senegalese sole [27], as well as for other species infected with different viruses [40–42, 46–48], including VHSV [11]. The pattern of ISG induction after VHSV infection was similar to poly I:C stimulation: powerful induction of Mx and Isg15 transcription and low Pkr transcription. Similar Isg15 transcriptional levels have been described in other flatfish after VHSV infection [15, 48].

Furthermore, the kinetics and transcriptional levels of the three ISG triggered by both VHSV isolates were similar. However, the relative quantification of the viral nucleoprotein gene showed earlier and higher replication levels of the pathogenic isolate, suggesting that lower levels of RNA of the non-pathogenic VHSV isolate induce the IFN response at the same level as the pathogenic VHSV isolate. This finding might represent an important difference between both isolates regarding the interaction with the host.

The protective role of the IFN I system against VHSV infections has been evaluated in poly I:C-inoculated juvenile Senegalese sole. Animals inoculated with the non-pathogenic VHSV isolate did not show any mortality, whereas the pathogenic VHSV isolate caused 68% cumulative mortality, which is similar to mortalities previously recorded in 20-g Senegalese sole intraperitoneally inoculated with a similar dose of the same viral isolate (50% at 60 dpi, [26]). This mortality was drastically reduced (5%) by the previous poly I:C inoculation (poly I:C + P VHSV group), indicating that IFN I system stimulated by poly I:C promotes protection against VHSV infection in Senegalese sole.

In addition, the IFN I system stimulated by poly I:C compromises the multiplication of both viral isolates, as has been demonstrated by the quantification of infective viral particles and viral genome. Thus, viral titer in poly I:C-treated animals was constant throughout time, whereas in non-stimulated fish (L15 + P VHSV or L15 + NP VHSV groups) the viral titer increased up to tenfold. Furthermore, the mean viral RNA relative values were always lower in the poly I:C-treated groups than in non-stimulated fish. Previous studies have also established an antiviral state after poly I:C inoculation in several fish species against different viruses [1, 49, 50]. Regarding flatfish, it has been reported that poly I:C-treated Japanese flounder were protected against VHSV infection [51], and poly I:C inoculation of Senegalese sole decreased IPNV replication [27].

The three ISG evaluated in the current study could be involved, along with other ISG, in the antiviral state triggered by poly I:C in Senegalese sole. In fact, antiviral activity against IPNV and VHSV has been previously described for Senegalese sole Mx [28], as well as for the three ISG in other fish species. Specifically, PKR antiviral activity has been described in Japanese flounder, in which the over-expression of the Pkr gene inhibited Scophtalmus maximus rhabdovirus (SMRV) multiplication [19]; the Mx antiviral properties have been determined in several fish species [3, 11]; and the ISG15 antiviral activity has been detected in Atlantic salmon and zebrafish (Danio rerio) [12, 14].

The comparative analysis of the ISG transcription after viral infection in poly I:C-treated and non-treated animals revealed that the pathogenic VHSV isolate negatively interfered with the stimulation of the ISG under study at 3 and 6 hpi, whereas infection with the non-pathogenic isolate did not affect the ISG stimulation triggered by poly I:C. This result suggests that the pathogenic VHSV isolate may interfere with the sole IFN I response at early stages of infection, likely in order to evade or limit the innate host defences.

It has been previously reported that the non-structural protein (NV) is involved in the VHSV antagonistic mechanisms. In fact, this protein suppresses the activity of the Japanese flounder Mx gene promoter and the early activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) in EPC cells [52]. In addition, this viral protein also has antiapoptotic effects in EPC cells at early stages of the viral infection [53]. However, further experiments would be necessary to confirm the involvement of the NV protein in the VHSV antagonism observed in the present study.

In summary, this study has demonstrated the main role of the IFN I system against VHSV infections in Senegalese sole by several lines of evidence. The antiviral state generated by poly I:C prevents VHSV infection in juvenile Senegalese sole, reducing the cumulative mortality and the viral replication. Furthermore, the marine VHSV isolate interferes negatively with the IFN I response, affecting the transcription of the three ISG tested at early stages of viral infection. As a consequence, the marine VHSV isolate replicates earlier and at higher levels than the non-pathogenic isolate, which does not show antagonistic effect against the IFN I system. Therefore, low levels of RNA of the freshwater VHSV induced transcription of ISG to similar levels as the marine one. The differences reported for both VHSV isolates may partly explain the lack of virulence of the freshwater isolate to Senegalese sole. Further analysis of the molecular mechanisms responsible for these differences could clarify the role of viral genes and/or ISG in the interaction between VHSV and the Senegalese sole IFN I system.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

analysis of variance

- CAB:

-

Carassius auratus blastulae embryonic cells

- cDNA:

-

complementary DNA

- CPE:

-

cytopathic effect

- dsRNA:

-

double-stranded RNA

- elF-2α:

-

eukaryotic initiation factor 2

- EPC:

-

epithelioma papolosum cyprini cell line

- FBS:

-

foetal bovine serum

- GS:

-

grouper spleen cells

- IHNV:

-

Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus

- IFN I:

-

type one interferon

- IP:

-

intraperitoneal

- IPNV:

-

Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis Virus

- ISG:

-

interferon stimulated gene

- ISG15:

-

interferon stimulated gene 15

- L15:

-

Leibovitz’s medium

- N:

-

nucleoprotein

- ND:

-

non-detected

- NF-κB:

-

nuclear factor kappa B

- NP:

-

non-pathogenic

- NV:

-

non-structural viral protein

- P:

-

pathogenic

- pi:

-

post-inoculation

- PKR:

-

protein kinase R

- Poly I:C:

-

polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid

- qRT-PCR:

-

quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- Rps4:

-

ribosomal protein S4

- RTG-2:

-

rainbow trout gonad cell line

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SMRV:

-

Scophtalmus maximus rhabdovirus

- SsMx:

-

Senegalese sole Mx protein

- TCID50 :

-

50% tissue culture infective dose

- Ubq:

-

ubiquitin

- VHS:

-

Viral haemorrhagic septicaemia

- VHSV:

-

Viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia Virus

- NNV:

-

Nervous Necrosis Virus

References

Langevin C, Aleksejeva E, Passoni G, Palha N, Levraud JP (2013) The antiviral innate response in fish: evolution and conservation of the IFN system. J Mol Biol 425:4904–4920

Kochs G, Reichelt M, Danino D, Hinshaw JE, Haller O (2005) Assay and functional analysis of dynamin-like Mx proteins. Methods Enzymol 404:632–643

Garcia-Rosado E, Alonso MC, Fernandez-Trujillo MA, Manchado M, Bejar J (2010) Characterization of flatfish Mx proteins. In: Nermann L, Meier S (eds) Veterinary immunology and immunopathology. Nova Science Publishers Inc, New York

Collet B (2014) Innate immune response of salmonid fish to viral infections. Develop Comp Immunol 43:160–173

Wu YC, Lu YF, Chi SC (2010) Antiviral mechanism of barramundi Mx against betanodavirus involves the inhibition of viral RNA synthesis through the interference of viral RdRp. Fish Shellfish Immunol 28:467–475

Haas AL, Ahrens P, Bright PM, Ankel H (1987) Interferon induces a 15-kilodalton protein exhibiting marked homology to ubiquitin. J Biol Chem 262:11315–11323

Loeb KR, Haas AL (1992) The interferon-inducible 15-kDa ubiquitin homolog conjugates to intracellular proteins. J Biol Chem 267:7806–7813

Dao CT, Zhang DE (2005) ISG15: a ubiquitin-like enigma. Front Biosci 10:2701–2722

Osiak A, Utermöhlen O, Niendorf S, Horak I, Knobeloch KP (2005) ISG15, an interferon-stimulated ubiquitin-like protein, is not essential for STAT1 signaling and responses against vesicular stomatitis and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Mol Cell Biol 25:6338–6345

Kim KI, Yan M, Malakhova O, Luo JK, Shen MF, Zou W, de la Torre JC, Zhang DE (2006) Ube1L and protein ISGylation are not essential for alpha/beta interferon signaling. Mol Cell Biol 26:472–479

Verrier ER, Langevin C, Benmansour A, Boudinot P (2011) Early antiviral response and virus-induced genes in fish. Dev Comp Immunol 35:1204–1214

Rokenes TP, Larsen R, Robertsen B (2007) Atlantic salmon ISG15: expression and conjugation to cellular proteins in response to interferon, double-stranded RNA and virus infections. Mol Immunol 44:950–959

Huang X, Huang Y, Cai J, Wei S, Ouyang Z, Qin Q (2013) Molecular cloning, expression and functional analysis of ISG15 in orange-spotted grouper, Epinephelus coioides. Fish Shellfish Immunol 34:1094–1102

Langevin C, van der Aa LM, Houel A, Torhy C, Briolat V, Lunazzi A, Harmache A, Bremont M, Levraud JP, Boudinot P (2013) Zebrafish ISG15 exerts a strong antiviral activity against RNA and DNA viruses and regulates the interferon response. J Virol 87:10025–10036

Pereiro P, Costa MM, Diaz-Rosales P, Dios S, Figureueras A, Novoa B (2014) The first characterization of two type I interferons in turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) reveals their differential role, expression pattern and gene induction. Develop Comp Immunol 45:233–244

Sudhakar A, Ramachandran A, Ghosh S, Hasnain SE, Kaufman RJ (2000) Phosphorylation of serine 51 in initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2 alpha) promotes complex formation between eIF2 alpha (P) and eIF2B and causes inhibition in the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of eIF2B. Biochemistry 39:12929–12938

Hu CY, Zhang YB, Huang GP, Zhang QY, Gui JF (2004) Molecular cloning and characterisation of a fish PKR-like gene from cultured CAB cells induced by UV inactivated virus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 17:353–366

Rothenburg S, Deigendesch N, Dittmar K, Koch-Nolte F, Haag F, Lowenhaupt K, Rich A (2005) A PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2 kinase from zebrafish contains Z-DNA binding domains instead of dsRNA binding domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1602–1607

Zhu R, Zhang YB, Zhang QY, Gui JF (2008) Functional domains and the antiviral effect of the double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase PKR from Paralichthys olivaceus. J Virol 82:6889–6901

Zenke K, Nam YK, Kim KH (2010) Molecular cloning and expression analysis of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PKR) in rock bream (Oplegnathus fasciatus). Vet Immunol Immunopathol 133:290–295

del Castillo S, Hikima JI, Ohtani M, Jung TS, Aoki T (2012) Characterization and functional analysis of two PKR genes in fugu (Takifugu rubripes). Fish Shellfish Immunol 32:79–88

Hu YS, Li W, Li DM, Liu Y, Fan LH, Rao ZC, Lin G, Hu CY (2013) Cloning, expression and functional analysis of PKR from grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Fish Shellfish Immunol 35:1874–1881

Skall HF, Olesen NJ, Mellergaard S (2005) Viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus in marine fish and its implications for fish farming-a review. J Fish Dis 28:509–529

Snow M, Bain N, Black J, Taupin V, Cunningham CO, King JA, Skall HF, Raynard RS (2004) Genetic population structure of marine viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV). Dis Aquat Organ 61:11–21

Moreno P, Olveira JG, Labella A, Cutrin JM, Baro JC, Borrego JJ, Dopazo CP (2014) Surveillance of viruses in wild fish populations in areas around the Gulf of Cadiz (South Atlantic Iberian Peninsula). Appl Environ Microbiol 80:6560–6571

Lopez-Vazquez C, Conde M, Dopazo CP, Barja JL, Bandin I (2011) Susceptibility of juvenile sole Solea senegalensis to marine isolates of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus from wild and farmed fish. Dis Aquat Organ 93:111–116

Fernandez-Trujillo MA, Ferro P, Garcia-Rosado E, Infante C, Alonso MC, Bejar J, Borrego JJ, Manchado M (2008) Poly I: C induces Mx transcription and promotes an antiviral state against sole aquabirnavirus in the flatfish Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis, Kaup). Fish Shellfish Immunol 24:279–285

Alvarez-Torres D, Garcia-Rosado E, Fernandez-Trujillo MA, Bejar J, Alvarez MC, Borrego JJ, Alonso MC (2013) Antiviral specificity of the Solea senegalensis Mx protein constitutively expressed in CHSE-214 cells. Mar Biotechnol 15:125–132

Alvarez-Torres D, Alonso MC, Garcia-Rosado E, Collet B, Bejar J (2014) Differential response of the Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) Mx promoter to viral infections in two salmonid cell lines. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 161:251–257

Lopez-Vazquez C, Dopazo CP, Barja JL, Bandin I (2007) Experimental infection of turbot, Psetta maxima (L.) with strains of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus isolated from wild and farmed marine fishes. J Fish Dis 30:303–312

Jensen MH (1963) Preparation of fish tissue culture for virus research. B World Health Organ 59:131–134

Jensen MH (1965) Research on the virus of Egtved disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 126:422–426

Reed LJ, Muench H (1938) A simple method of estimating 50 per cent end-points. Am J Hyg 27:493–497

Heppell J, Berthiaume L, Tarrab E, Lecomte J, Arella M (1992) Evidence of genomic variations between infectious pancreatic necrosis virus strains determined by restriction fragment profiles. J Gen Virol 73:2863–2870

Nishizawa T, Mori K, Nakai T, Iwao F, Kiyokuni M (1994) Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of RNA of striped jack nervous necrosis virus (SJNNV). Dis Aquat Organ 18:103–107

Lopez-Vazquez C, Dopazo CP, Olveira JG, Barja JL, Bandin I (2006) Development of a rapid, sensitive and non-lethal diagnostic assay for the detection of viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus. J Virol Methods 133:167–174

Olveira JG, Souto S, Dopazo CP, Bandin I (2013) Isolation of betanodavirus from farmed turbot Psetta maxima showing no signs of viral encephalopathy and retinopathy. Aquaculture 406:125–130

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25:402–408

Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F (2002) Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol 3 (RESEARCH0034)

Plant KP, Harbottle H, Thune RL (2005) Poly I: C induces an antiviral state against Ictalurid Herpesvirus 1 and Mx1 transcription in the channel catfish (Ictalurus punctatus). Dev Comp Immunol 29:627–635

Lockhart K, McBeath AJ, Collet B, Snow M, Ellis AE (2007) Expression of Mx mRNA following infection with IPNV is greater in IPN-susceptible Atlantic salmon post-smolts than in IPN-resistant Atlantic salmon parr. Fish Shellfish Immunol 22:151–156

Tafalla C, Chico V, Perez L, Coll JM, Estepa A (2007) In vitro and in vivo differential expression of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Mx isoforms in response to viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus (VHSV) G gene, poly I: C and VHSV. Fish Shellfish Immunol 23:210–221

Zenke K, Kim KH (2009) Molecular cloning and expression analysis of three Mx isoforms of rock bream, Oplegnathus fasciatus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 26:599–605

Bravo J, Acosta F, Padilla D, Grasso V, Real F (2011) Mx expression in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata, L.) in response to poly I:C, bacterial LPS and chromosomal DNA: preliminary study. Fish Shellfish Immunol 31:170–172

Falco A, Miest JJ, Pionnier N, Pietretti D, Forlenza M, Wiegertjes GF, Hoole D (2014) B-Glucan-supplemented diets increase poly(I:C)-induced gene expression of Mx, possibly via Tlr3-mediated recognition mechanism in common carp (Cyprinus carpio). Fish Shellfish Immunol 36:494–502

O’Farrell C, Vaghefi N, Cantonnet M, Buteau B, Boudinot P, Benmansour A (2002) Survey of transcript expression in rainbow trout leukocytes reveals a major contribution of interferon-responsive genes in the early response to a rhabdovirus infection. J Virol 76:8040–8049

Purcell MK, Kurath G, Garver KA, Herwig RP, Winton JR (2004) Quantitative expression profiling of immune response genes in rainbow trout following infectious haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHNV) infection or DNA vaccination. Fish Shellfish Immunol 17:447–462

Avunje S, Wi-Sik K, Chang-Su P, Myung-Joo O, Sung-Ju J (2011) Toll-like receptors and interferon associated immune factors in viral haemorrhagic septicaemia virus infected olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Fish Shellfish Immunol 31:407–414

Nishizawa T, Takami I, Kokawa Y, Yoshimizu M (2009) Fish immunization using a synthetic double-stranded RNA Poly (I:C), an interferon inducer, offers protection against RGNNV, a fish nodavirus. Dis Aquat Organ 83:115–122

Oh MJ, Takami I, Nishizawa T, Kim WS, Kim CS, Kim SR, Park MA (2012) Field tests of poly(I:C) immunization with nervous necrosis virus (NNV) in seven band grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus (Thunberg). J Fish Dis 35:187–191

Kim WS, Kim JO, Cho JK, Oh MJ (2014) Change of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) titer in olive flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) following Poly(I:C) administration. Aquacult Int 22:1175–1179

Kim MS, Kim KH (2013) The role of viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV) NV gene in TNF-α- and VHSV infection-mediated NF-κB activation. Fish Shellfish Immunol 34:1315–1319

Ammayappan A, Vakharia VN (2011) Nonvirion protein of novirhabdovirus suppresses apoptosis at the early stage of virus infection. J Virol 85:8393–8402

Infante C, Matsuoka MP, Asensio E, Cañavate JP, Reith M, Manchado M (2008) Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in larvae from flatfish using real-time PCR. BMC Mol Biol 9:28

Benzekri H, Armesto P, Cousin X, Rovira M, Crespo D, Merlo MA, Mazurais D, Bautista R, Guerrero-Fernandez D, Fernandez-Pozo N, Ponce M, Infante C, Zambonino JL, Nidelet S, Gut M, Rebordinos L, Planas JV, Begout M-L, Claros MG, Manchado M (2014) De novo assembly, characterization and functional annotation of Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis) and common sole (Solea solea) transcriptomes: integration in a database and design of a microarray. BMC Genom 15:952

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DA-T, MCA, EG-R, JB and IB are responsible for the experiment design, interpretation of data and revision of this manuscript. DA-T performed all the experimental infections, sampling, sample processing and result analyses. AMP has also been involved in the sample processing and primer design. MCA and EG-R have also been responsible for the writing of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate the laboratory assistance of Patricia Moreno (University of Malaga), Sandra Souto and Carmen Lopez-Vazquez (University of Santiago de Compostela). This study was funded by the project P09-CVI-4579 from Junta de Andalucía (proyectos de Excelencia de la Junta de Andalucía), and partially by the CSD2007-00002 Aquagenomics grant (funded by the program Consolider-Ingenio 2010) from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia (MEC). D. Alvarez-Torres was supported by a fellowship from Junta de Andalucía (Proyecto de Excelencia P09- CVI-4579).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Alvarez-Torres, D., Podadera, A.M., Bejar, J. et al. Role of the IFN I system against the VHSV infection in juvenile Senegalese sole (Solea senegalensis). Vet Res 47, 3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-015-0299-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13567-015-0299-4