Abstract

Background

Epididymal tumors, especially malignant tumors, have low incidence and are rare in our clinical work. However, they may progress quickly and have poor prognosis. For such rare clinical cases with extremely low incidence rates, and as they are prone to misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis and have a very poor prognosis, clinical workers need to pay special attention and consider the possibility of primary epididymal malignant tumors.

Case report

A 63-year-old Chinese male patient from Asia was admitted due to scrotal pain. Upon examination, an abnormal lesion was found in the right epididymal region. After thorough evaluation, surgical resection was performed, and the postoperative pathological result confirmed the presence of epididymal adenocarcinoma. After further ruling out secondary lesions, primary epididymal adenocarcinoma was considered. Right retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was performed under laparoscopic for treatment, and 1/11 lymph node metastasis was detected after surgery. The patient is currently under close follow-up.

Conclusions

The number of clinical cases of primary epididymal malignant tumors is very limited, there is currently no standardized diagnosis and treatment process, and there is a lack of systematic evaluation methods regarding the effectiveness of different treatment options such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. In addition, the outcome is difficult to predict. In this article, we reviewed relevant literature and systematically elaborated on the diagnosis and treatment of epididymal malignant tumors, hoping to provide useful information for relevant experts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary malignant tumors of the epididymis are rare clinical diseases, and the incidence rate is less than 7% of overall male genital system tumors. The age range of its onset is wide, but it is more common between the ages of 30 years and 50 years, which is 10 years later than the average age of onset for benign tumors of the epididymis. Among them, the age distribution of patients with different pathological types varies, and embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma occurs earlier. To date, the youngest patient reported in China is only 14 months old. The onset age of adenocarcinoma is relatively older, generally over 40 years [1]. There is no relevant report on the difference in incidence rate between different regions or races. Primary malignant tumors of the epididymis are mostly unilateral, with more tumors on the left side. Moreover, tumors are mostly located in the tail of the epididymis, and bilateral cases are very rare. Due to their anatomical characteristics, epididymal tumors are theoretically easy to find. However, as the hidden clinical symptoms and the fact that epididymal masses are mostly benign tumors, chronic inflammatory nodules, or sperm stasis, the incidence of malignant tumors is low, leading to low alertness of clinical physicians to them, thus delaying the time of diagnosis and treatment. At the same time, epididymal malignant tumors are highly malignant tumors and prone to metastasis early with poor prognosis. Moreover, most of the domestic and foreign literature consists of case reports rather than systematic research. Therefore, a relatively standardized diagnosis and treatment mode has not yet been determined [2].

Case report

A 63-year-old Chinese male patient from Asia visited our hospital on 1 August 2021, due to “swelling and pain in the right testicle for over a year” who had a history of surgical treatment for left testicular hydrocele and was without other special medical experiences and allergy history regarding food and drugs, no history of exposure to significant carcinogenic factors, and no obvious family history of tumors. Physical examination: normal vital signs, height 178 cm, weight 74 kg, no swelling of superficial lymph nodes throughout the body, intact scrotal skin, no redness, swelling or pain. The size and morphology of the left testicular epididymis were normal, with slightly lower activity. The size of the right testicle was close to normal, and there was a nodule about 4 cm × 4 cm in size in the upper and posterior epididymal area. The texture was hard, with poor mobility and no obvious squeezing pain. Scrotal ultrasound showed an irregular cystic mass in the right epididymis area that was tightly adhered to the right testicle, exhibiting an uneven mixed echo mass with unclear boundaries. The size of the lump was approximately 4 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) prompted the following description: right epididymis was full; within it, there was a range of approximately 2.6 cm × 2.8 cm × 2.1 cm mixed signals of cystic and solid nature; boundary was not smooth, especially in the junction area to the upper edge of the right testicle (Fig. 1). Retroperitoneal computed tomography (CT) and chest CT did not show important positive results. The levels of alpha fetoprotein (3.6 ng/mL), human chorionic gonadotropin (0.3 mIU/mL), and lactate dehydrogenase (220 IU/L) were all within the normal range.

Preliminary clinical diagnosis

Tumor of the right epididymis

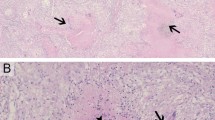

The nature of the patient’s right epididymis tumor was uncertain, and a malignant tumor could not be ruled out. After sufficient communication with the patient and his family on feasible management measures, the patient chose to undergo radical resection of the right testicular epididymis directly. With sufficient preparation, we performed radical resection of the right testis and epididymis through a right inguinal incision. The postoperative gross specimen was described as follows: the right testicle with the epididymis was completely cut, measuring 5.5 cm × 5 cm × 3 cm in size; the epididymis was 3 cm × 2.5 cm × 2 cm in size; upon incision, gray yellow spongy testicular tissue was observed, and a gray white lump with a size of approximately 3.5 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm was visible in the epididymis; the surface of the lump was gray white and solid in nature; under the microscope, the tumor cells had varying structures, large nuclei, obvious atypia, deeply stained cytoplasm, and glandular-like structures (Fig. 2).

The immunohistochemical results were as follows: PCK(+), EMA(+), CEA(−), WT-1(+), CK5/6(+), CR(calretinin)(+), CD30(−), SALL4(−), Ki-67(20%), OCT-3/4(−), CK7(+), β-catenin(cytoplasm)(+), inhibin-α(−), MC(HBME-1)(−), D2-40(−), pax-8(−), and Cam5.2(+). Microscopic morphology and immunohistochemical results supported epididymal adenocarcinoma with testicular invasion. Perineural invasion was identified, and no tumor thrombus was found in the vessels. Further gastroscopy, colonoscopy, electronic laryngoscopy, neck enhanced MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET)-CT examinations did not indicate the possibility of tumors in other parts of the body. Therefore, we considered the final diagnosis as primary adenocarcinoma of the right epididymis. Considering the high malignancy of primary adenocarcinoma of the epididymis and its susceptibility to retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis, some scholars have pointed out that retroperitoneal lymph node dissection should be performed not only in cases with lymph node enlargement, but also as a preventive treatment for clinical N0 patients [3]. Therefore, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was recommended for this patient.

The laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymph node dissection was performed 2 weeks later. During the surgery, we removed the entire right retroperitoneal lymphoid adipose tissue and checked the wound surface to ensure that there was no obvious bleeding point. After repeatedly rinsing the wound with sterile distilled water, we removed the specimen tissues (Fig. 3). The overall appearance of the postoperative specimens was described as follows: a piece of gray yellow adipose tissue with a size of 7.5 cm × 4.5 cm × 2.5 cm; several nodules with a diameter of 0.5–3 cm were observed inside, and all nodules were taken; The microscopic examination results were as follows: 11 lymph nodes were found, with one lymph node showing cancer metastasis (1/11).

Screenshots of the right retroperitoneal lymph node dissection under laparoscopy: (1) clearing retroperitoneal fat; (2) opening perirenal fascia (3) exposing the ureter; (4) exposing vena cava (5) the upper edge of the dissection exceeded the level of the renal artery; (6) exposing the aorta and lymph tissues between the abdominal aorta and vena cava; (7) exposing the contralateral renal vein; (8) overall view after dissection. The black arrows indicate the main anatomical structures described in each image

Postoperative diagnoses

-

Primary malignant tumor of the right epididymis,

-

Adenocarcinoma,

-

Secondary malignant tumor in the right retroperitoneal lymph node.

Follow-up situation

After multidisciplinary discussions and evaluations, the surgery completely removed the tumor tissue. Under sufficient communication with the patient and their family on feasible treatment measures, they decided not to accept adjuvant measures such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and strict follow-up had been chosen. At 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months, and 30 months after surgery, the imaging showed no progression. As of now, no additional adjuvant treatment has been added, and close follow-up is continuing.

Discussion

Primary malignant tumors of the epididymis are rare clinical diseases, there is currently no standardized diagnosis and treatment process, and there is a lack of systematic evaluation methods of the effectiveness regarding different treatment options such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, and targeted therapy. We want to review relevant literature and systematically elaborate on the diagnosis and treatment of epididymal malignant tumors in this paper.

Risk factors of primary malignant tumors

The existing relevant literature has not systematically elucidated the high-risk factors for primary epididymal malignant tumors, but there are currently no relevant reports on whether cryptorchidism or testicular insufficiency is related to the occurrence of epididymal malignant tumors. However, some literature has mentioned the relationship between cryptorchidism or undescended testis and epididymal malignant tumors, but whether there is a relationship between them is still uncertain [4].

Clinical symptoms

Primary malignant tumors of the epididymis lack specific symptoms and signs, mostly manifesting as painless masses within the scrotum, mostly located in the tail of the epididymis, followed by the head. Some patients have local soreness or pain accompanied by a sense of heaving. The masses often exhibit progressive growth, with a diameter often greater than 3 cm and unclear boundaries with surrounding tissues. They can be accompanied by thickening of the affected spermatic cord or vas deferens, appearing nodular or beaded on palpation. When accompanied by hydrocele of the tunica vaginalis, the testicular volume substantially increases, and the transparency test can be positive. Some patients also have acute epididymitis, and the affected testis and epididymis are also considerably enlarged, with obvious tenderness, redness, and swelling of the scrotal skin and a notable increase in skin temperature. In severe cases, purulent secretions may be present [5]. When tumors metastasize locally or remotely, corresponding symptoms and signs are observed.

Laboratory examinations

Early clinical laboratory examinations may show no important abnormalities, and in cases of acute inflammation, white blood cell count, neutrophil count, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and other indicators in the blood can be considerably higher than the normal range. When the disease progresses to the terminal stage, important abnormalities in various blood indicators may occur, such as electrolyte disorders, severe hypoproteinemia, liver and kidney dysfunction, and elevated alkaline phosphatase. As of now, there are no reports suggesting specific tumor markers for primary epididymal malignant tumors. Common tumor markers related to testicular malignant tumors, such as blood alpha fetoprotein (AFP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), are mostly normal. However, secondary malignant tumors in the epididymis may exhibit specific abnormal tumor markers, such as a substantial increase in blood prostate specific antigen (PSA) when prostate malignant tumors metastasize to the epididymis [4].

Imaging examinations

Malignant tumors of the epididymis have a complex tissue source and thus lack typical imaging manifestations. High-resolution ultrasound is considered the preferred imaging examination method for testicular and epididymal tumors due to its noninvasive and convenient advantages. It can provide some common features: irregular and large (usually larger than 3 cm) cystic, mixed cystic and solid, or solid masses in the epididymal or epididymal spermatic cord area. Tumors are prone to invading surrounding tissues such as the spermatic cord, testicles, or scrotal skin. The morphology of the testes and epididymis is often unclear when the tumor is large. Epididymal malignant tumors often have an abundant blood supply, but the manifestations of tumors from different tissue sources vary. They can be accompanied by testicular hydrocele and considerable thickening of the spermatic cord. At the same time, ultrasound can also be used to carefully explore the bilateral spermatic cord area, pelvic cavity, and retroperitoneal area to determine whether there is lymph node enlargement [6]. CT can also clearly display abnormal density lesions near the testicles within the scrotum and clarify the relationship between the tumor and the epididymis, and enhanced scanning can assist in determining the blood supply of the tumor. MRI often shows irregular nodules on the lateral side of the testis, closely related to the epididymis. The internal signals of the nodules are uneven, and the enhanced scan can show gradual enhancement, mainly with edge enhancement. Magnetic resonance imaging diffusion weighted imaging (MRI-DWI) is significantly limited in diffusion, and MRI can also be useful in determining local and distant metastasis. Craniocerebral CT or MRI, emission computed tomography (ECT) bone scan, positron emission computed tomography (PET-CT), among others, can all be used as supplementary examinations [7].

Methods of tumor tissue acquisition for pathological diagnosis

Due to its rarity and lack of specific clinical manifestations, it is difficult to make a clear diagnosis before surgery for primary malignant tumors of the epididymis. Fu et al. [8, 9] reported that there were very few cases of epididymal tumors that were clearly diagnosed before surgery, and most of them were misdiagnosed as other epididymal diseases, with a misdiagnosis rate of 63%. Regarding preoperative needle aspiration cytology examination, Smith et al. reported that the examination could lead to approximately 0.006% malignant tumor implantation, while Andersson et al. [10, 11] concluded that the possibility of implantation metastasis through fine needle aspiration was basically negligible, confirming the feasibility of this method. However, after careful analysis of the relevant literature, it was found that needle aspiration cytology is not a routine choice for patients with relatively limited lesions. More people choose to undergo direct surgical exploration followed by intraoperative rapid freezing examination, the results of which guide further comprehensive treatment measures.

Pathological types of malignant tumors in the epididymis

Epithelial malignant tumors of the epididymis are relatively rare, and most of them originate from interstitial tissue. Among all pathological types, adenocarcinoma is more common in clinical practice, followed by embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma [12]. The remaining tissue types are relatively complex, and different pathological types have different clinical characteristics and prognosis outcomes, which are often difficult to determine before surgery and postoperative pathological analysis. The main types of primary epididymal malignant tumors that are commonly reported in domestic and foreign literature are presented in Table 1.

Differential diagnosis of malignant tumors in the epididymis

Primary epididymal malignant tumors mainly need to be differentiated from diseases such as epididymal cyst, granuloma of the epididymis, chronic epididymitis, epididymal tuberculosis, benign tumors of the epididymis, and secondary malignant tumors of the epididymis according to medical history, physical examinations, preoperative imaging data, laboratory results, needle aspiration cytology or biopsy, and intraoperative and postoperative pathological results.

Metastasis of malignant tumors in the epididymis

Common metastasis pathways of epididymal malignant tumors: the most common metastasis pathways of epididymal malignant tumors are hematogenous metastasis and lymphatic metastasis. The lymphatic circulation of the epididymis is similar to that of the testis, and the lymphatic vessels of the two coincide with each other. Their collecting lymphatic vessels follow the internal arteries and veins of the spermatic cord, passing through the seminal vesicle, spermatic cord, inguinal segment, and abdominal segment from the beginning and injecting into the corresponding lymph nodes through the retroperitoneal space. The most common sites of lymphatic metastasis are the common iliac lymph nodes and retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and regardless of whether there is local metastasis, metastasis to retroperitoneal lymph nodes may have already occurred. Therefore, some scholars advocate for routine retroperitoneal lymph node dissection after radical epididymectomy for malignant tumors of the epididymis [27]. Other scholars suggest that patients younger than the age of 10 years do not need to undergo retroperitoneal lymph node dissection if preoperative imaging examinations do not indicate enlarged lymph nodes, while patients older than the age of 10 years must undergo retroperitoneal lymph node dissection if preoperative CT suggests possible lymph node metastasis [28]. The most common sites of hematogenous metastasis are the liver and lungs; metastasis to these sites can occur in the early stages of poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma, and the literature suggests that these patients often die within 8 months of diagnosis [5].

Treatment measures

Treatment principles: at present, when considering the possibility of epididymal malignant tumors, we prioritize preoperative comprehensive evaluation and direct surgical exploration when conditions permit, assist with rapid frozen biopsy during surgery, and then formulate follow-up plans on the basis of the results. If the results indicate a benign tumor, the tumor or epididymis should be removed. If a malignant tumor is considered, radical resection of the epididymis tumor through the inguinal approach is performed, including the tumor, epididymis, testicle, spermatic cord, and tunica vaginalis. When the tumor invades the scrotum, unilateral scrotal resection is needed. If lymph node metastasis in the spermatic cord, pelvic cavity, or retroperitoneal area is considered before surgery, active regional lymph node dissection is recommended [6, 29, 30]. Further comprehensive treatment measures will be determined on the basis of pathological results after surgery. Among them, if the pathological results indicate adenocarcinoma, even if there are no obvious signs of lymph node metastasis temporarily, as it is the main mode of metastasis, active performance of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection supplemented by chemotherapy after surgery is still recommended. Sarcomas are mainly treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, while undifferentiated cancers are mainly treated by radiotherapy with adjuvant chemotherapy if necessary [7].

Conclusion

As oncologists or surgeons, we should carefully consider the possibility of malignant tumors when facing patients with epididymal tumors. We recommend direct surgical exploration and complete resection of the lesion in one stage, but performing needle aspiration cytology examination before resection to confirm diagnosis is also a feasible option [10, 11]. When pathological result indicates primary adenocarcinoma of the epididymis, retroperitoneal lymph node dissection should be actively performed, and systemic treatments such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy may be temporarily avoided under close follow-up [14, 31]. For other pathological types of malignant tumors, comprehensive measures such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be actively taken, referring to relevant information [7, 12, 19, 21, 32].

Availability of data and materials

PubMed was used as a source of information using the search term: epididymal malignant tumor OR epididymis AND malignancy, epididymis AND cancer, epididymis AND tumor.

Abbreviations

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

Computer tomography

- PCK:

-

Pan cytokeratin

- EMA:

-

Epithelial membrane antigen

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- WT-1:

-

Wilms tumor gene

- CK:

-

Cytokine

- CR:

-

Calretinin

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

- SALL4:

-

Spalt-like transcription factor 4

- Ki-67:

-

Nuclear protein Ki-67

- OCT3/4:

-

POU structural transcription factor

- MC:

-

Member of mesothelial markers

- CAM:

-

Cell adhesion molecule

- ECT:

-

Emission computed tomography

- PET:

-

Positron emission tomography

References

Wang L, Mo HT, Shi M, Wang J, Dai B, et al. Report of 5 cases of primary malignant tumors of the epididymis. Chin J Urol. 2002;23(1):53 (In Chinese).

Yin B, Song YS, Fei X, Shan LP, Zhang H, et al. Report of 4 cases of primary malignant tumors of the epididymis. Chin Androl. 2006;12(10):944 (In Chinese).

Michal S, Jan D, Daniel M, Antonin K, Radek L. Primary adenocarcinoma of the epididymis: the therapeutic role of retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(4):1049–53.

Zhou SJ, Ma LM, Cai XQ, Zhang YP. Diagnosis and treatment of primary malignant tumors of the epididymis (with a clinical report of 5 cases). Clin Treatises. 2010;17(4):36–8 (In Chinese).

Tan YB, Zhang NX. Surgical diagnostic pathology. 1st ed. Tianjin: Tianjin Science and Technology Press; 2000. p. 639–40 (In Chinese).

Jing JG, Li YZ, Peng YL, Luo Y, Zhuang H, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of 5 cases of primary malignant tumors of the epididymis. Acoust Technol. 2015;34(4):282–6 (In Chinese).

Guo YL, Hu LQ. Clinical andrology. Wuhan: Hubei Science and Technology Press; 1996. p. 213 (In Chinese).

Fu Q, Wang F, Li S, Lv J, Ding K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary epididymal tumors (report of 27 cases). Clin Oncol China. 2007;(09):519–520 (In Chinese).

Lin DH, Lu SJ, Xing B, Du ZJ, Chen MS, et al. Endovascular intervention therapy for acute lower limb arterial occlusion. Hainan Med J. 2007;18(10):3–4.

Smith EH. Complications of percutaneous abdominal fine-needle biopsy. Radiology. 1991;178(1):253.

Andersson R, Andren-Sandberg A, Lundstedt C, Tranberg KG. Implantation metastases from gastrointestinal cancer after percutaneous puncture of drainage. Eur J Surg. 1996;162(7):551.

Xu ZQ, Xu HY, Qiu XW. Report of two cases of embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma of the epididymis. Chin J Surg. 1990;11(6):366 (In Chinese).

Ruan Y, Fan J, Xia SJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of small round cell malignant tumors of the epididymis (one case report and literature review). Chin Clin Oncol. 2006;33(16):952–3 (In Chinese).

Jones MA, Young RH, Scully RE. Adenocarcinoma of the epididymis: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21(12):1474–80.

Li DD, Bai TN, Han RF, Lu BX, Wang JZ, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary epididymal leiomyosarcoma. Shandong Med J. 2012;52(48):98–9 (In Chinese).

Li WP, Zhao Y, Guo XQ, Wang YM, Zhang HF, et al. Report on 3 cases of primary malignant tumors of the epididymis and literature review. Chin J Androl. 2014;20(1):92–4 (In Chinese).

Li WM, Song LH, Fei FL. Embryonic rhabdomyosarcoma of the testis (report of two cases and literature review). Henan J Oncol. 1996;4:301–2 (In Chinese).

Fan QH, Zhu XZ, Lai RQ. Soft tissue pathology. Nanchang: Jiangxi Science and Technology Press; 2003. p. 78–9 (In Chinese).

Wang KY, Shi H, Mao WP, Li WY, Wu ZL, et al. Rare epididymal-derived myoepithelial carcinoma: a case report and review of literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2020;50(3):391–6.

Li ZW, Xiang J, Yan S, Gao F, Zheng S. Malignant triton tumor of the retroperitoneum: a case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;30(10):96.

Gao LJ, Song HL, Mu K, Wang JX, Guo BY, et al. Primary epididymis malignant triton tumor: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Med Res. 2015;20(1):79.

Liguori G, Garaffa G, Trombetta C, Bussani R, Bucci R, et al. Inguinal recurrence of malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis: one case report with delayed recurrence and review of the literature. Asian J Androl. 2007;9(6):859–60.

Suh JY, Jeong H, Kim YA. Primary malignant B-cell lymphoma of the epididymis. Urol Case Rep. 2015;4:27–9.

Zuo C, Zou L, Zhang XY, Liu CH, Sun B, et al. Wait A case report of primary malignant tumor of the epididymis and literature review. Modern Biomed Progr. 2013;25(13):4905–7 (In Chinese).

Sarvis JA, Auge BK. Myeloid (granulocytic) sarcoma of epididymis as rare manifestation of recurrent acute myelogenous leukemia. Urology. 2009;73(5):1163.e1-3.

Li Q, Guan Y, Hu YP, Yang P. One case of primary epididymal adenosquamous cell carcinoma with multiple metastases. J Clin Urol. 2020;35(5):421–2 (In Chinese).

Zhang Y, Sun YC, Chen XS, Gao W. Report of 7 cases of primary epididymal tumors. Chin J Androl. 2003;9(3):229–30 (In Chinese).

Stewart RJ, Martelli H, Oberlin O, Rey A, Bouvet N, et al. Treatment of children with nonmetastatic paratesti-cular rhabdomyosarcoma: results of the malignant mesenchymal tumors studies(MMT 84 and MMT 89) of the international society of pediatric oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(5):793–8.

Matsumoto F, Onitake Y, Shimada K. Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma presenting with a giant abdominos-crotal hydrocele in a toddler. Urology. 2016;87:200–1.

Kourda N, Atat REI, Derouiche A, Bettaib I, Baltagi S, et al. Paratesticular pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in an adult: diagnosis and management. Cancer Radiother. 2007;11(5):280–3.

Stanik M, Dolezel J, Macik D, Krpenshy A, Lakomy R. Primary adenocarcinoma of the epididymis: the therapeutic role of retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2012;44(4):1049–53.

Wang DY, Qian WQ, Sun ZQ, Song JD. Diagnosis and treatment of primary epididymal tumors. J Clin Urol. 2005;20(6):349–51 (In Chinese).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JX and QW conceived the paper’s objective and collected the patient’s data. ZD, YY, and HY analyzed the data and performed reference search. JX, YY, and HY drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, J., You, Y., Dong, Z. et al. Treatment of primary epididymal adenocarcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 18, 274 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04590-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-024-04590-4