Abstract

Background

Adenomatoid tumor is a very rare benign neoplasm of mesothelial origin affecting mainly female and male genital tracts. The diagnosis is challenging as this tumor mimics many differential diagnoses. The current literature offers only some case reports and short series of adenomatoid tumors.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old patient with unremarkable medical history presented for chronic mild pain of the right testis evolving for months. The physical examination shows a palpable right intrascrotal nodule of 10 mm in greatest diameter. The nodule was painful, mobile with firm consistency. The laboratory investigations were within normal limits, the scrotal ultrasonography showed a well-circumscribed predominantly hyperechoic intrascrotal nodule in the right epididymal head with heterogeneous echostructure. Excisional biopsy of the lesion was performed and the histopathological analysis showed a well-circumscribed tumor with microcystic and trabecular architecture made of small interconnected tubules and cysts lined by flattened cells with prominent vacuolization and thread-like bridging strands, consistent with an epididymal adenomatoid tumor. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged. Four months after surgical treatment, the patient has no sign of the disease.

Conclusion

Testicular adenomatoid tumors are uncommon benign neoplasms with diagnostic challenge. Adenomatoid tumors arising in epididymis are managed by excisional biopsy with testis-sparing surgery avoiding unnecessary orchidectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Adenomatoid tumor is a very rare benign neoplasm affecting mainly female and male genital tracts [1,2,3]. However, other extra-genital organs can be involved by adenomatoid tumors, such as adrenal gland, pleura, mediastinum, mesentery, omentum, liver and gastrointestinal tract [4,5,6,7,8]. The name “adenomatoid tumor” was first introduced by Golden and Ash as the origin of these tumors was controversial in 1945 when they reported their study [9]. It is now well established that adenomatoid tumors have a mesothelial origin as supported by many immunohistochemical and other molecular studies [1, 10]. In fact, although many locations have been reported, adenomatoid tumors usually develop next to serosal surfaces (mesothelial cell lining) of the involved organs.

Adenomatoid tumors of the male genital tract involve mainly the paratesticular region and the epididymis, rarely they develop within the testicular parenchyma [11,12,13,14,15,16]. They mimic many differential diagnoses as the preoperative diagnostic modalities lack specificity (imaging techniques mainly), and the definitive diagnosis relies on the histopathological analysis of the resected specimens. The current literature offers only some case reports and short series of adenomatoid tumors [1,2,3, 10].

We report herein additional case of a right epididymal adenomatoid tumor in a 47-year-old patient that presented with chronic testicular pain. The diagnosis was made by histopathological analysis of the resected lesion and the patient recovered well after surgery.

2 Case presentation

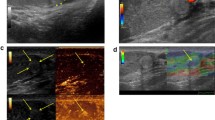

A 47-year-old patient presented for chronic mild pain of the right testis evolving for months. The patient had unremarkable medical history and he had no chronic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure or other chronic illnesses. On physical examination, he had good general health conditions, the urological examination shows a palpable right intrascrotal nodule of 10 mm in greatest diameter. The nodule was painful, mobile with firm consistency. The contralateral testis was normal. There was no inguinal mass or lymphadenopathy. The pelvis, abdomen and thorax were normal on physical examination. The laboratory investigations were within normal limits (blood, liver and renal function tests). Serological tests of tumor markers were also within normal range: serum alpha fetoprotein, beta human chorionic gonadotrophin, alkaline phosphatase and prostate-specific antigen (PSA). Scrotal ultrasonography showed a well-circumscribed predominantly hyperechoic intrascrotal nodule of 10 × 10 mm in the right epididymal head with heterogeneous echostructure. The other testicular components were normal. The left testis was normal without any lesion. There were no other lesions in the pelvis or in other parts of the abdominal cavity. A surgical treatment was decided. A trans-scrotal approach was performed, the surgical exploration revealed a well-defined right 10 mm epididymal nodule without involvement of the testicular parenchymal tissue (Fig. 1). A testicular-preserving surgery was performed with the complete resection of the nodule that has been sent for histopathological analysis. The resected specimen measured 10 × 10 mm with a firm consistency and a whitish homogeneous whorled cut surface. The histopathological analysis showed a well-circumscribed tumor with microcystic and trabecular architecture made of small interconnected tubules and cysts lined by flattened cells with prominent vacuolization in some areas with a signet-ring appearance (Fig. 2). Thread-like bridging strands were observed in some tumor parts (Fig. 3). The nuclei were oval with bland appearance and small nucleoli. There were no atypia, mitoses or necrosis. The tumor stroma was fibrous with scattered inflammatory lymphocytes sometimes arranged in follicles (Fig. 4). These histopathological features were characteristic of an adenomatoid tumor. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged from hospital. Four months after surgical treatment, the patient has no sign of the disease.

3 Discussion

Adenomatoid tumor is a rare benign neoplasm that affects mainly paratesticular regions accounting for a third of all neoplasms of this anatomical area [16, 17]. The epididymal tail is the most location of this tumor, the epididymal head is rarely affected. Usually, patients’ age ranges from 20 to 66 years with a mean age of 46–50 years, the occurrence in children being very uncommon [2, 3, 17, 18]. Unlike their female genital tract counterpart that are commonly found incidentally, male genital tract adenomatoid tumors are usually symptomatic lesions presenting with chronic testicular pain or swelling [2, 3]. Our current case has a classic epidemiological and clinical presentation, a part from the tumor location involving epididymal head as the tail is the most affected part of the epididymis in previous reports [1].

Ultrasonography (US) is widely used to investigate intrascrotal and paratesticular tumors. Adenomatoid tumors appear as a well-defined homogeneous hypoechoic or hyperechoic nodule with no increased blood flow on color Doppler US [11, 16, 19, 20]. Adenomatoid tumors with intratesticular growth, especially when arising in tunica albuginea, tunica vaginalis or the rete testis, mimic malignant testicular tumors [12, 13, 15, 16]. The computed tomography scan (CT scan) or the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in cases where malignancy is suspected as these techniques allow better assessment of the tumor and its relation with the surrounding tissues [11]. In our patient, there was no clinical suspicion of malignancy and the US assessment showed a predominantly hyperechoic lesion suggesting an epididymal cyst.

Testicular adenomatoid tumors are usually well-circumscribed lesions lacking fibrous capsule, arising in the epididymis, rarely in testicular tunica with secondary involvement of the parenchyma [1]. They present as firm nodules of around 1 cm in greatest diameter, rarely exceeding 2 cm [2, 3]. The cut surface is homogeneous, whitish sometimes whorled [2]. Our case has characteristic gross features of adenomatoid tumor: a well-circumscribed firm nodule measuring 1 cm with homogeneous whitish whorled cut surface.

On microscopic examination, adenomatoid tumors appear with microcystic, angiomatoid or trabecular architecture, solid or macrocystic patterns are rarely reported [1, 9]. The tumor’s stroma is usually fibrous with scattered lymphocytes, but sometimes the stroma may have prominent smooth muscle tissue, leading some authors to name the lesion as leiomyoadenomatoid tumor [1, 19,20,21]. The cells vary from flattened to vacuolated with abundant cytoplasm. The nuclei are oval, bland, centrally located with a small nucleolus [1,2,3, 9]. These vacuolated cells are very characteristic of adenomatoid tumors [9]. They contain prominent cytoplasmic vacuoles with only thin cytoplasmic strands connecting them, referred to as “thread-like bridging strands” [1, 9]. These strands bridge the lumina of the tubular and slit-like spaces of the tumor [1]. The vacuolated cells also appear as signet-ring cells especially when cells have small vacuoles and are arranged in trabeculae, posing a serious diagnostic challenge with metastatic carcinomas. On immunohistochemical analysis, adenomatoid tumors express classic mesothelial markers such as pancytokeratin, WT1 (Wilm’s tumor protein-1) calretinin, D2-40 or HBME-1 (human bone marrow endothelial cell marker-1), the proliferative index (Ki-67) being less than 10% [1,2,3]. In our current case, the definitive diagnosis was reached without the need for immunohistochemistry as morphological features were characteristic: a well-circumscribed epididymal nodule with predominantly microcystic architecture with bland-looking cells and prominent vacuolated cells showing the characteristic thread-like bridging strands. However, in certain instances especially in unusual locations (intratesticular parenchymal growth), infarcted tumors with reactive atypias, predominantly solid or macrocystic architectures, many differential diagnoses could be evoked and immunohistochemical analysis should be required. Table 1 summarizes some differential diagnoses of testicular adenomatoid tumors. The most important differential diagnosis to rule out is the malignant mesothelioma. Diagnostic challenges appear especially with well-differentiated mesothelioma and with malignant mesothelioma with adenomatoid tumor features. Malignant mesotheliomas have classically ill-defined borders with substantial cellular atypia and mitoses. Immunohistochemical markers that can be useful in these instances are BAP1 (BRCA1-associated protein-1) that is positive in adenomatoid tumors and negative in malignant mesothelioma, L1CAM (L1 cell adhesion molecule) also positive in adenomatoid tumors and negative in malignant mesothelioma [1, 10, 22, 23]. Also, CK5/6 (cytokeratin 5/6) is classically strongly positive in malignant mesothelioma while negative or focally positive in adenomatoid tumors [1, 22]. The other classic mesothelial markers, like WT1, calretinin, D2-40 and HBME-1, have no discriminative value as they are positive in both malignant mesothelioma and adenomatoid tumors [1]. Vascular lesions (hemangioma and lymphangioma) are very rare in the testis, their diagnosis can be easily ruled out by the negative immunostaining with mesothelial markers and their positive staining with endothelial markers like CD34 (cluster of differentiation 34), CD31, ERG, factor VIII-related antigen [1,2,3, 10, 11]. Of note lymphangioma express D2-40 like other mesothelial tumors [1]. Spermatocele is a common epididymal cystic lesion resulting from dilatation of rete testis or epididymal efferent ductules by obstructive mechanisms [24,25,26]. Predominantly, cystic adenomatoid tumor may mimic spermatocele clinically, radiologically and histopathologically. However, spermatocele does not express mesothelial markers but express epithelial markers of epididymal ductules such as CK7, PAX8 and androgen receptor (AR) [27]. Adenomatoid tumors arising in tunica albuginea or tunica vaginalis with intratesticular growth are very rare and pose diagnostic challenge with primary testicular germ cell tumors [12, 13, 28]. On microscopic analysis, the microcystic architecture and vacuolated cells of adenomatoid tumors can be mistaken for yolk sac tumor; however, this tumor shows sometimes characteristic perivascular arrangement of tumor cells called Schiller–Duval bodies, and they express SALL4, alpha feto-protein (AFP), glypican 3, CDX2 (caudal-related homeobox gene 2) with negative mesothelial markers on immunohistochemistry [1, 13].

The origin of adenomatoid tumors has been controversial previously, but now it is well established that they are of mesothelial origin as they express phenotypic markers related to mesothelial cells [1,2,3, 9]. The pathogenesis of adenomatoid tumors is not well understood. Several cases have been reported in immunocompromised patients treated for autoimmune diseases or organs transplantation or HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection [1, 10]. Recently, a study by Goode et al. has tried to investigate the association of adenomatoid tumors of the male and female genital tract with immune dysregulation and found that they are genetically defined by TRAF7 mutation, a member of the family of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) that drives aberrant NF-kB pathway activation [10]. TRAF7 encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase that has been implicated in regulation of a number of critical immunomodulatory signaling pathways involving NF-kB (nuclear factor-kappa B), illustrating in part the link between adenomatoid tumors and immune dysregulation [10]. Our patient had no reported immune disease, supporting the fact that other causative mechanisms may be involved. In fact in the study reported by Goode et al., only 40% of their patients with available clinical history had a history of immune dysregulation [10].

Adenomatoid tumors are benign neoplasms with no reported malignant transformation or potential recurrence after complete surgical resection [2, 3, 11]. Unnecessary orchidectomy should be avoided and surgery ideally limited to excisional biopsy of the lesion through inguinal or scrotal approach [11, 19, 20]. In our case, the preoperative diagnosis was epididymal cyst and excision of the lesion was performed with testicular-preserving surgery. However, tumors with intratesticular growth have been managed aggressively by orchidectomy [12, 13, 18, 28].

4 Conclusion

Testicular adenomatoid tumors are very rare benign neoplasms. They pose diagnostic challenges and the definitive diagnosis relies on the histopathological analysis of the resected specimens. Adenomatoid tumors arising in epididymis are managed by excisional biopsy with testis-sparing surgery avoiding unnecessary orchidectomy.

Availability of data and materials

All data of this study are included in this article.

Abbreviations

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic imaging resonance

- WT1:

-

Wilm’s tumor protein-1

- CK:

-

Cytokeratin

- AR:

-

Androgen receptor

- BAP1:

-

BRCA1-associated protein-1

- L1CAM:

-

L1 cell adhesion molecule

- HBME-1:

-

Human bone marrow endothelial cell marker-1

- AFP:

-

Alpha feto-protein

- CDX2:

-

Caudal-related homeobox gene 2

- TRAF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- NF-kB:

-

Nuclear factor-kappa B

- CD:

-

Cluster of differentiation

References

Karpathiou G, Hiroshima K, Peoc’h M (2020) Adenomatoid tumor: a review of pathology with focus on unusual presentations and sites, histogenesis, differential diagnosis, and molecular and clinical aspects with a historic overview of its description. Adv Anat Pathol. 27:394–407. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAP.0000000000000278

Wachter DL, Wünsch PH, Hartmann A, Agaimy A (2011) Adenomatoid tumors of the female and male genital tract. A comparative clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 47 cases emphasizing their site-specific morphologic diversity. Virchows Arch. 458:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-011-1054-5

Sangoi AR, McKenney JK, Schwartz EJ, Rouse RV, Longacre TA (2009) Adenomatoid tumors of the female and male genital tracts: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 44 cases. Mod Pathol 22:1228–1235. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2009.90

Varkarakis IM, Mufarrij P, Studeman KD, Jarrett TW (2005) Adenomatoid of the adrenal gland. Urology 65:175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.026

Minato H, Nojima T, Kurose N, Kinoshita E (2009) Adenomatoid tumor of the pleura. Pathol Int 59:567–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02407.x

Hissong E, Graham RP, Wen KW, Alpert L, Shi J, Lamps LW (2022) Adenomatoid tumours of the gastrointestinal tract - a case-series and review of the literature. Histopathology 80:348–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.14553

Goto M, Uchiyama M, Kuwabara K (2016) Adenomatoid tumor of the mediastinum. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 64:47–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-014-0419-5

Yeh C-J, Chuang W-Y, Chou H-H, Jung S-M, Hsueh S (2008) Multiple extragenital adenomatoid tumors in the mesocolon and omentum. APMIS 116:1016–1019. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0463.2008.01084.x

Golden A, Ash JE (1945) Adenomatoid tumors of the genital tract. Am J Pathol 21:63–79

Goode B, Joseph NM, Stevers M, Van Ziffle J, Onodera C, Talevich E et al (2018) Adenomatoid tumors of the male and female genital tract are defined by TRAF7 mutations that drive aberrant NF-kB pathway activation. Mod Pathol 31:660–673. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.153

Amin W, Parwani AV (2009) Adenomatoid tumor of testis. Clin Med Pathol 2:17–22. https://doi.org/10.4137/cpath.s3091

Sun AY, Polackwich AS, Sabanegh ES (2016) Adenomatoid tumor of the testis arising from the tunica albuginea. Rev Urol 18:51–53

Alexiev BA, Xu LF, Heath JE, Twaddell WS, Phelan MW (2011) Adenomatoid tumor of the testis with intratesticular growth: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol 19:838–842. https://doi.org/10.1177/1066896911398656

Alam K, Maheshwari V, Varshney M, Aziz M, Shahid M, Basha M et al (2011) Adenomatoid tumour of testis. BMJ Case Rep. 2011:bcr0120113790. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3790

Pacheco AJ, Torres JLM, de la Guardia FVD, Arrabal Polo MA, Gómez AZ (2009) Intraparenchymatous adenomatoid tumor dependent on the rete testis: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Urol 25:126–128. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.45551

Rafailidis V, Huang DY, Sidhu PS (2021) Paratesticular lesions: aetiology and appearances on ultrasound. Andrology 9:1383–1394. https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.13021

Lioe TF, Biggart JD (1993) Tumours of the spermatic cord and paratesticular tissue. A clinicopathological study Br J Urol 71:600–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16033.x

Liu W, Wu R, Yu Q (2011) Adenomatoid tumor of the testis in a child. J Pediatr Surg 46:E15-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.06.020

Almohaya N, Almansori M, Sammour M, Ajjaj AB, Yacoubi MT (2021) Leiomyoadenomatoid tumors: a type of rare benign epididymal tumor. Urol Case Rep 38:101700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2021.101700

Wazwaz B, Murshed K, Musa E, Taha N, Akhtar M (2020) Epididymal leiomyoadenomatoid tumor: a case report with literature review. Urol Case Rep 32:101226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eucr.2020.101226

Cazorla A, Algros M-P, Bedgedjian I, Chabannes E, Camparo P, Valmary-Degano S (2014) Epididymal Leiomyoadenomatoid Tumor: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Curr Urol 7:195–198. https://doi.org/10.1159/000365675

Weissferdt A, Kalhor N, Suster S (2011) Malignant mesothelioma with prominent adenomatoid features: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 10 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol 15:25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2010.08.005

Yang L-H, Yu J-H, Xu H-T, Lin X-Y, Liu Y, Miao Y et al (2014) Mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis testis with prominent adenomatoid features: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 7:7082–7087

Lundström K-J, Söderström L, Jernow H, Stattin P, Nordin P (2019) Epidemiology of hydrocele and spermatocele; incidence, treatment and complications. Scand J Urol 53:134–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681805.2019.1600582

Basar H, Baydar S, Boyunaga H, Batislam E, Basar MM, Yilmaz E (2003) Primary bilateral spermatocele. Int J Urol 10:59–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00567.x

Crossan ET (1920) SPERMATOCELE. Ann Surg 72:500–507. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000658-192010000-00009

Magers MJ, Udager AM, Chinnaiyan AM, French D, Myers JL, Jentzen JM et al (2016) Comprehensive immunophenotypic characterization of adult and fetal testes, the excretory duct system, and testicular and epididymal appendages. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 24:e50-68. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAI.0000000000000326

Monappa V, Rao ACK, Krishnanand G, Mathew M, Garg S (2009) Adenomatoid tumor of tunica albuginea mimicking seminoma on fine needle aspiration cytology: a case report. Acta Cytol 53:349–352. https://doi.org/10.1159/000325324

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

All of the authors have no funding sources to declare relevant to this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BE wrote the article, made substantial contributions to conception and design of the article; IB, DS, ABAB, ISC, HHK, HSB and HN made critical assessment of the article. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of the patient’s clinical details and clinical images was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Efared, B., Boubacar, I., Soumana, D. et al. Epididymal adenomatoid tumor: a case report and literature review. Afr J Urol 28, 59 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00329-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00329-z