Abstract

Background

Otis urethrotomy can sometimes lead to troublesome bleeding after seemingly uneventful procedures. This case report highlights one such case which went unnoticed initially; the bleeding was erroneously ascribed to the prostate, thereby falsely indicting the “decoy” prostate.

Case presentation

A 78-year-old Asian gentleman was referred to our hospital with complaint of intractable bleeding after undergoing laser enucleation of prostate at another institute, wherein he further underwent unsuccessful bilateral angioembolization of pudendal arteries. On endoscopy (for hemostasis), we found a spurting vessel in the navicular fossa, which was effectively controlled.

Conclusions

This case report highlights the importance of performing prompt endoscopy in case of uncontrolled bleeding after prostate endoscopic surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Otis urethrotomy occasionally results in uncontrollable bleeding after seemingly straightforward surgeries. This case report focuses on one such instance that initially went undiscovered; the bleeding was mistakenly attributed to the prostate, and was swiftly taken care of by a simple procedure.

Case presentation

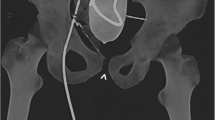

A 78-year-old Asian gentleman (who was on dual anti-platelet drugs, in addition to being diabetic and hypertensive) underwent laser anatomic enucleation of prostate for benign enlargement of the prostate, at another institute. The patient was off anti-platelet medications for 1 week prior to enucleation surgery. The patient had per-urethral bleeding (without the initiation of anti-platelet medications) starting from the 3rd post-operative day (as soon as the 22 French tri-way Foley’s catheter was removed), and was re-admitted at the same institute; penile jacketing was done, perineal compression was given and he received 4 blood transfusions. Despite such conservative measures, the bleeding continued intermittently, and the patient underwent bilateral angioembolization of the internal pudendal arteries along with unilateral angioembolization of a bulbar artery. However, the bleeding continued intermittently and the patient was then referred to our institute.

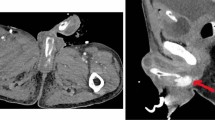

After optimizing the patient with resuscitative intravenous fluids, we took the patient for cystoscopy (anti-platelet drugs were still kept on hold), under spinal anesthesia (see Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4).

The vessel was fulgurated using a roller-ball attached to monopolar electrocautery, with a 30-degree telescope and 26 French sheath. Glycine was used as the irrigating fluid. Also, a suture was taken over the glans (with the suture knot outside), incorporating the site of the bleeding vessel, taking care that the meatus was not stenosed (allowing enough space for insertion of an 18 French Foley’s catheter)

After controlling the bleeding, the patient was kept off antiplatelet drugs for 7 days, after which they were restarted. Foley’s catheter was removed on the 2nd post-operative day, and the patient had an uneventful recovery.

Discussion

Hemorrhage in the resected area is a common complication both during and after TURP, and every effort should be made to achieve hemostasis during the operation, to prevent the need for a return to the operating room. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study of 3885 patients found a transfusion rate of 2.5% [1]. Other early data reported high transfusion rates with over 20% of patients receiving transfusion [2], and more recent data from an analysis of RCTs found that 4.4% of patients would require transfusion [3].

Urethrorrhagia, a rare urological disorder, is described as continuous or intermittent active urethral bleeding irrespective of urination. Massive bleeds following internal urethrotomy have been described in literature, sometimes resulting in bulbourethral artery pseudoaneurysm [4]. Severe urethrorrhagia following traumatic catheterization (resulting in pseudoaneurysm of distal branches of the internal pudendal artery, requiring internal pudendal artery angioembolization) has also been described [5]. Deep cuts into the corpus spongiosum and, occasionally, the corpora cavernosa through the scar tissue are the most common causes of bleeding after OIU. Most of the time, mild bleeding stops on its own or with external compression. Urethrorrhagia following OTIS urethrotomy is considered by some as evidence of deep urethrotomy, and has even been held responsible for ensuing fibrotic process leading to ventral penile curvature [6].

Managing bleeding from the fossa navicularis can be challenging, since endoscopically, it is very difficult to gain access to an area which is situated near the tip of the penis (the irrigant also is unable to effectively distend this part of the urethra, due to continuously being drained through the external urethral meatus; hence vision is compromised). We suggest that the navicular fossa (the site of bleeding in the index case), being anatomically more capacious than the penile urethra, is ineffectively compressed especially by smaller-lumen Foley’s catheters (leading to loss of the tamponade effect of per-urethral catheters in this region) (as shown in Fig. 5).

Conclusion

Urethrorrhagia is an uncommon and unexpected complication after TURP/prostate enucleation; in this case it was attributable to the ancillary procedure of an Otis urethrotomy. Endoscopy should be the initial step in the management approach of uncontrollable bleeding after prostate surgery. Angioembolization can prove futile in the management of bleeding due to Otis urethrotomy, and simpler alternatives must be attempted.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- TURP:

-

Transurethral resection of prostate

- OIU:

-

Optical internal urethrotomy

References

Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, Cockett AT, et al. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications. A cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141(2):243–7.

Doll HA, Black NA, McPherson K, et al. Mortality, morbidity and complications following transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hypertrophy. J Urol. 1992;147(6):1566–73.

Mayer EK, Kroeze SG, Chopra S, et al. Examining the “gold standard”: a comparative critical analysis of three consecutive decades of monopolar transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) outcomes. BJU Int. 2012;110(11):1595–601.

Attri V, Parmar K, Dewana S, Sharma G, Chandna A. Massive bleed following optical internal urethrotomy: an unforeseen doom discussing the unique management technique. J Endourol Case Rep. 2018;4(1):179–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/cren.2018.0076.

Taha DE, Hariri A, Bahdilh S, et al. Urethral pseudoaneurysm life-threatening bleeding: a case report and literature review of etiological and treatment options. Afr J Urol. 2022;28:52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00321-7.

Karaguzel E, Gur M, Tok DS, Kazaz IO, Eren H, Kutlu O, Ozgur GK. Severe penile curvature following Otis urethrotomy. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013: 214082. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/214082.

Acknowledgements

Department of Urology, PGIMER, Chandigarh, India

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RSD—manuscript writing, editing. UKM—conceptualization, supervision, operating surgeon.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mete, U.K., Deshpande, R.S. Confronting urethrorrhagia after Otis urethrotomy: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 522 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04261-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04261-w