Abstract

Background

Deep neck space infections are uncommon in infants. Retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) is a deep space neck infection that can present with subtle signs and symptoms. Delay in diagnosis can lead to life-threatening complications. Here we describe life-threatening complication of retropharyngeal abscess.

Case presentation

We report a life-threatening complication of retropharyngeal abscess in 10-month old Asian infant weighing 8.2 kg. The patient presented with fever, right-sided neck swelling, hoarseness of voice, and respiratory distress. The clinical and radiological findings were suggestive of airway obstruction complicated by retropharyngeal abscess. The patient was urgently taken to the operating room and underwent (grade 3) intubation. After stabilization, the patient underwent endoscopic trans-oral incision and drainage, during which 5 cc pus was aspirated. Antibiotics were prescribed for 2 weeks following the procedure based on the sensitivity result of the pus culture.

Conclusion

In retropharyngeal abscess, a delay in diagnosis can result in life-threatening complications. This report highlights the importance of prompt recognition of a threatened airway and the management of retropharyngeal abscess by emergency physicians. If an emergency physician suspects RPA with airway obstructions, the airway should be immediately secured in a secure environment by otolaryngologist and an anesthesiologist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) is defined as an abscess in the space between the buccopharyngeal fascia and the prevertebral fascia [1]. It is more common in children under the age of 5 years and has winter-spring seasonality [2]. Upper respiratory tract infection is the most common cause of deep neck infections in children, followed by odontogenic origin, as compared to foreign body such as fish bones and trauma is being the most common cause in adults [3, 4]. Early diagnosis and management can prevent life-threatening complications such as airway obstructions, mediastinitis, and tracheitis. We report the case of 10-month old infant with airway obstruction complicated by retropharyngeal abscess. In this case report, we discuss timely recognition of threatened airway and management of retropharyngeal abscess.

Case presentation

A previously healthy 10-month-old Asian infant (body weight 8.2 kg), was referred to us from secondary care with complaints of fever, right-sided neck swelling for ten days, and hoarseness of voice with respiratory distress for 3 days. The patient household had satisfactory socioeconomic, and their parents were not consanguineous, living with siblings in the same residence. The infant received exclusively breast milk until 6 months of age, at which time a weaning diet was initiated. At the time of presentation, the infant was still on a weaning diet.

The child's clinical examination revealed fever with a temperature of 39.2 degrees Celsius, tachycardia with a heart rate of 176 beats per minute, a blood pressure of 114/59 mmHg and a respiratory rate of 45 breaths per minute. The neck examination revealed bilateral swelling more prominent at the right lateral aspect of the neck. Systemic examination showed increased work of breathing with resting stridor, indicative of airway obstruction. The rest of systemic examinations was unremarkable.

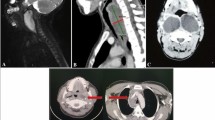

Ultrasound neck examination revealed bilateral enlarged cervical lymph nodes of varying sizes, with the largest on the right side 15 mm*10 mm and 12 mm*7.9 mm on the left side. Laboratory testing revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 30.2 k/L and a left shift. Blood analysis revealed 53% neutrophils, 0.3% eosinophils, 6.3% monocytes, 39.2% lymphocytes, 9.4 g/dL hemoglobin, 1113 k/L platelets, 72.5 mg/L C-reactive protein, and pH 7.43, 30.3 mmHg partial pressures of carbon dioxide and 211 mmHg partial pressures of oxygen, 19.8 meq/L bicarbonate, and − 3.5 meq/L base excess. The first dose of intravenous antibiotic Ceftriaxone at a dose of 65 mg/kg/day was administered. The patient was urgently taken to the operating room, where the child intubated for airway protection by an on-call anesthesia consultant. The intubation was grade 3 and was done with video laryngoscopy, as shown in Fig. 1A and B. Computed tomography of the neck showed a large rim-enhancing fluid collection in the retropharyngeal space with extension in to right paravertebral space with surrounding inflammatory changes, cervical lymphadenopathy, as shown in Fig. 2. The patient was mechanically ventilated, intubated, and admitted to the Pediatric Intensive care unit. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, including intravenous ceftriaxone (65 mg/kg/dose once daily), vancomycin (15 mg/kg/dose every eight hourly) and metronidazole (10 mg/kg/dose every eight hourly) were administered. Otolaryngology was consulted urgently, and endoscopic trans-oral incision and drainage were performed, during which 5 cc pus was aspirated and it was immediately transported to the laboratory. Gram stain of Pus was negative. Pus culture revealed enterococci, Candida albicans, while tracheal culture and Gram stain for klebs-loffler were negative. The antibiotic was deescalated to Amoxicillin + clavulanic acid (30 mg/kg/dose every eight hourly), and oral fluconazole (10 mg/kg/dose once daily) was started for Candida albicans. Blood cultures were taken on two occasions, but both results were negative for aerobes and anaerobes. Post-procedure, the patient had an uneventful PICU course, was extubated on the second postoperative day. During the recovery phase, he was kept NPO initially and then he received nasogastric feeding, with breast-feeding resuming on the fourth postoperative day. The progression of feeding was based on patient clinical condition, which was well tolerated. Antibiotics were administered to the patient for a total of 2 weeks along with ten days of antifungal treatment. Follow-up appointments with the infectious disease and surgical team were scheduled to monitor progress and address any active issues, and the patient was discharged in stable condition on the fifth postoperative day. The patient returned to our hospital 1 week after discharge for follow-up appointment, during which their condition was reassessed and it was observed that patient health had improved since their previous visit.

Contrast enhanced CT images through the neck. A Peripherally enhancing collection is identified in the retropharyngeal region, with extension along the paravertebral muscles on right side into the right posterior neck suggestive of retropharyngeal abscess formation (white arrowhead). B Additionally loculi of abscesses are identified within the muscle planes of right posterior neck. C Image at the level of superior mediastinum shows no evidence of extension of abscess into the mediastinum. D Midline sagittal image shows the inferior extent of the lesion to be terminating in hypopharynx

Discussions

This case report describes a life-threatening complication of retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) in a 10-month-old Asian infant presenting with fever, right-sided neck swelling, hoarseness of voice, and respiratory distress. A part from existing literature, we highlight the development of rare complication such as airway obstruction by RPA, and prompt multidisciplinary management in securing the airway and successfully treating the abscess.

Sign and symptoms of retropharyngeal abscess are similar to upper respiratory tract infections. Fever, sore throat, and torticollis are early symptoms of deep space neck infection, whereas late symptoms include respiratory distress, hoarseness, neck stiffness, and stridor [5]. Delay in diagnosis can lead to life-threatening complications, such as airway obstruction, mediastinitis, cavernous sinus thrombosis, and rupture of abscess in the trachea or pharynx. Retropharyngeal abscess is polymicrobial caused by both aerobes and anaerobes; therefore, it requires antibiotics that are effective against all potential pathogens [6].

The most common organisms that are usually associated with deep neck infections are Staphylococcus aureus, S. viridans, Klebsiella pneumonia, Bacteroides, and Peptostreptococcus [7].

In symptomatic patients, computed tomography (CT) scan is highly sensitive (92%) in diagnosing abscess [8]. The CT scan determines the extent of abscess and involvement of adjacent structures. CT neck findings, coupled with clinical symptoms are helpful in surgical planning. However, in a well-child with retropharyngeal abscess, positive findings of lateral cervical X-ray coupled with clinical symptoms should suffice in diagnosing and managing the abscess conservatively [8].

Treatment options for retropharyngeal abscess range from a prolonged course of intravenous antibiotics to surgical drainage. Surgery is indicated in patients with a retropharyngeal abscess greater than 2.5 cm on CT scan, as in our case, RPA with complications, and patients with small RPA who are not responding to empiric antibiotics up to 48 h. The surgical approach depends on the site of the abscess. The external approach is preferred for uncomplicated cases, such as superficial abscess, and patients in whom adjacent vital structures are displaced medially, as on CT scan findings [7]. Intraoral approaches is superior in selected cases and have the advantage of short hospital stays, less morbidity, lower hospital cost and avoiding neurovascular injuries, as in our case. Patients with RPA less than 2.5 cm and non-symptomatic RPA should be conservatively managed with empiric antibiotics. Empiric intravenous antibiotics should be started as soon as possible, and the choice of empiric antibiotics should include penicillin combination with beta-lactamase inhibitor (Clavulanic acid and ampicillin-sulbactam) or beta-lactamase-resistant (Cefoxitin, Cefuroxime, imipenem, and meropenem), coupled with antianerobic antibiotics (metronidazole, clindamycin). The incidence of community-acquired methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus is increasing in deep neck space infections [9, 10]. The adjustment of antibiotic should be done as per the culture report and clinical response of patient. In our case report, we started with ceftriaxone, vancomycin, and metronidazole and then deescalated to oral Augmentin and fluconazole, as per culture report. Intravenous antibiotics should continue until the patient shows improvement and becomes afebrile [11].

A small amount of edema in the airway can cause significant airway obstruction in infants. Intubation is very difficult in patients who present with airway obstruction secondary to deep neck space infection. Direct laryngoscopy and multiple unsuccessful attempts can puncture the abscess and cause aspiration of pus, which can lead to pneumonitis, tracheitis, and bronchitis. Patient with suspected RPA presenting with signs of airway obstruction, such as tripod or sniffing position, cyanosis, unable to speak, and tachypnea with grunting, should involve an anesthesiologist and otolaryngologist in promptly securing airway in a controlled setting, as in our case.

Conclusion

Delay in the diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess can lead to life-threatening complications. The management of RPA is multidisciplinary and involves various teams, including intensivists, otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists, and infectious disease specialists. If emergency physician suspect RPA with airway obstructions, the airway should be promptly secured by otolaryngologist and anesthesiologist in a secure environment. Once the airway is secured, a CT scan with contrast should be performed. Clinical symptoms coupled with CT scan neck finding can guide regarding surgical or conservative management.

Strength and limitation of our case report

This case report present a rare and life-threatening complication of retropharyngeal abscess with airway obstruction, and highlights the importance of multidisciplinary team approach in providing timely and lifesaving intervention in such cases.

Management of such cases will be challenging especially in resource limited setting where the expertise are limited in maintenance of emergent airway, so timely and early referral of these patients would help to adequate facility would make an impact.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- RPA:

-

Retropharyngeal abscess

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- OR:

-

Operating room

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- NPO:

-

Nil per oral

References

Akhavan M. Ear, nose, throat: beyond pharyngitis: retropharyngeal abscess, peritonsillar abscess, epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis, and postoperative tonsillectomy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2021;39:661–75.

Woods CR, Cash ED, Smith AM, Smith MJ, Myers JA, Espinosa CM, Chandran SK. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscesses among children and adolescents in the United States: epidemiology and management trends, 2003–2012. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2016;5:259–68.

Weed HG, Forest LA. Deep neck infection. In: Cummings C, Flint P, Harker L, editors. Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby; 2005. p. 2515–22.

Harkani A, Hassani R, Ziad T, et al. Retropharyngeal abscess in adults: five case reports and review of the literature. Sci World J. 2011;11:1623–9.

Vinckenbosch P, Guilcher P, Lambercy K, Richard C. Retropharyngeal abscess in children. Rev Med Suisse. 2017;13:1698–702.

Brook I. Microbiology of retropharyngeal abscesses in children. Am J Dis Child. 1987;141(2):202–4.

Lawrence R, Bateman N. Controversies in the management of deep neck space infection in children: an evidence-based review. Clin Otolaryngol. 2017;42:156–63.

Grisaru-Soen G, Komisar O, Aizenstein O, et al. Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess in children–epidemiology, clinical features and treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1016–20.

Naidu SI, Donepudi SK, Stocks RM, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a pathogen in deep neck abscesses: a pediatric case series. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:1367–71.

Fleisch AF, Nolan S, Gerber J, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a cause of extensive retropharyngeal abscess in two infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26:1161–3.

Abudinen-Vasquez S, Marin MN. Management of pediatric head and neck infections in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2020;17:1–24.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR: Data Acquiring, Writing the manuscript and final revision of manuscript, SK: Literature search of topic, HP, QA and AA: final revision of manuscript NR: Concept and design, interpretation of data, final revision of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rehman, A.U., Khan, S., Abbas, A. et al. Life-threatening complication of retropharyngeal abscess in an infant: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 367 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04101-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-023-04101-x