Abstract

Background

Mutations or polymorphisms of genes that are associated with inflammasome functions are known to predispose individuals to Crohn’s disease and likely affect clinical presentations and responses to therapeutic agents in patients with Crohn’s disease. The presence of additional gene mutations/polymorphisms that can modify immune responses may further affect clinical features, making diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease even more challenging. Whole-exome sequencing is expected to be instrumental in understanding atypical presentations of Crohn’s disease and the selection of therapeutic measures, especially when multiple gene mutations/polymorphisms affect patients with Crohn’s disease.

Case summary

We report the case of a non-Hispanic Caucasian female patient with Crohn’s disease who was initially diagnosed with pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome with fluctuating anxiety symptoms at 9 years of age. This patient was initially managed with pulse oral corticosteroid treatment and then intravenous immunoglobulin due to her immunoglobulin G1 deficiency. At 15 years of age, she was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease, following onset of acute abdomen. Treatment with oral corticosteroid and then tumor necrosis factor-α blockers (adalimumab and infliximab) led to remission of Crohn’s disease. However, she continued to suffer from chronic abdominal pain, persistent headache, general fatigue, and joint ache involving multiple joints. Extensive gastrointestinal workup was unrevealing, but whole-exome sequencing identified two autosomal dominant gene variants: NLRP12 (loss of function) and IRF2BP2 (gain of function). Based on whole-exome sequencing findings, infliximab was discontinued and anakinra, an interleukin-1β blocker, was started, rendering marked improvement of her clinical symptoms. However, Crohn’s disease lesions recurred following Yersinia enterocolitis. The patient was successfully treated with a blocker of interleukin-12p40 (ustekinumab), and anakinra was discontinued following remission of her Crohn’s disease lesions.

Conclusion

Loss-of-function mutation of NRLRP12 gene augments production of interleukin-1β and tumor necrosis factor-α, while gain-of-function mutation of IRF2BP2 impairs cytokine production and B cell differentiation. We propose that the presence of these two autosomal dominant variants caused an atypical clinical presentation of Crohn’s disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inflammasomes are cytosolic protein complexes involved in innate immune responses, sensing nonspecific signals through pattern recognition receptors that belong to a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor (NLR) family [1]. Upon these signals, inflammasomes convert pro-interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-8 into active forms and release them. Most NLR family members are associated with inflammasomes that promote inflammatory responses, while NLR protein 12 (NLRP12) exerts suppressive actions [1]. Autosomal dominant LOF mutations of NLRP12 cause familial autoinflammatory syndrome [2]. NLRP12 also plays a role in intestinal homeostasis, in part promoting bacterial tolerance in the gut [3]. In rodent models, NLRP12 deficiency leads to colitis caused by an increase in production of TNF-α and IL-6 [3]. LOF NLRP12 mutations were reported to cause autoinflammatory syndrome [2]. In patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBDs), polymorphism of NLRP12 is associated with changes in TNF-α production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [4]. Therefore, individuals with LOF NLRP12 variants are likely prone to IBD and may present with symptoms observed in patients with autoinflammatory syndromes.

The availability of WES began to disclose that the presence of additional mutations can alter the clinical presentation of NLRP12 variants. Tal et al. reported a case of NLRP12 mutation with a variant of toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) which presented as severe esophagitis of human simplex virus (HSV) and CD without periodic fever [5]. A child with variants of POLR3A and NLRP12 reportedly presented with recurrent acute disseminated encephalomyelitis/optic neuritis along with familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome [6].

The presented case was initially diagnosed with PANS, with favorable responses to pulse OCS and then IVIg. However, the patient subsequently developed CD and revealed atypical responses to TNF-α blockers. WES identified AD variants of NLRP12 and IRF2BP2. A GOF mutation of IRF2BP2 is reported in familial common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), resulting in impairment of B cell differentiation, and production of T cell/monocyte cytokines. In the presented case, the presence of these two variants appears to have resulted in a puzzling array of clinical features.

Case presentation

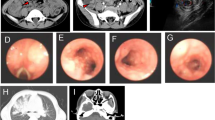

The presented case is a non-Hispanic Caucasian female who was diagnosed with PANS at age 9 years, following acute onset of severe anxiety that manifested as separation anxiety and school phobia. Tics, and other physical symptoms typically seen in PANS patients, were not present as per her parents. The patient was initially treated with ibuprofen, and then OCS. The patient responded favorably to pulse OCS therapy initially. Secondary to persistently low immunoglobulin 1 (IgG1), the patient was referred to the Pediatric Allergy/Immunology Clinic at age 10 years. Her condition was stable for the next 2 years with prophylaxis antibiosis (azithromycin) only. At age 12 years, following a viral syndrome, a major exacerbation of anxiety occurred and a high dose IVIg (1 gram/kg/dose x2) caused a severe adverse reaction (nausea, vomiting, and severe headache). Supplemental IVIg (0.8 g/kg/dose every 3 weeks) to prevent recurrent respiratory infection was well tolerated, with resolution of her anxiety symptoms. However, at age 15 years, sudden onset of acute abdomen resulted in a visit to the emergency room. Abdominal pain progressively worsened over the next several months. She was eventually diagnosed with CD based on biopsy findings: CD lesions in the terminal ileum. Her CD was treated with oral budesonide (Entocort EC) for 1 month without improvement. Thus, adalimumab 7.5 mg subcutaneous (SQ) injection every 2 weeks was started, and then switched to 7. 5 mg SQ every week, resulting in improvement of her gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms with resolution of CD lesions 8 months after weekly adalimumab 7.5 mg SQ. However, she suffered from severe joint symptoms; she was found to have positive antihistone antibody and thought to have had drug-induced lupus. Therefore, adalimumab was switched to infliximab IV (300 mg/dose) every 8 weeks and then eventually ever 4 weeks. Switching to infliximab IV infusion led to onset of severe fatigue/headache and adverse reactions to IVIg (joint ache, headache, skin rash, and malaise). Part of her pain symptoms were attributed to subcutaneous nerve entrapment at that time. Prior to the start of TNF-α blockers, she tolerated IVIg without any adverse reactions. During the next 12 months, she continued to have severe fatigue, headache, joint ache, and recurrence of abdominal pain without symptomatic relief by changing Ig infusion from IV to SQ routes. Various regimens of pre- and post-medications for IVIg provided no symptomatic relief. The results of extensive GI workup exploring the organic causes affecting intestine, pancreas, and liver were unrevealing. Because of her puzzling clinical features, we turned to genetic analysis. WES revealed AD variants of NLRP12 [C.1054>T, minor allele frequency (MAF) 0.04%] and IRF2BP2 (c.1180A>C, MAF 0.006%), and heterozygous, autosomal recessive, pathological variant of ATM (c.7089+2T>G). GOF mutations of IRF2BP2 were reported to cause hypogammaglobulinemia, suppressing production of cytokines and B cell differentiation [7]. NLRP12 is reported to have a role in gut immune homeostasis, and the mutation found in this case is reported in two patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome (CAPS) [8]. These variants are inherited from her father. Interestingly, the paternal grandmother, who was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, did not respond well to TNF-α inhibitors either, as per her parents. Prior to this genetic workup, the presented case was diagnosed with low Von Willebrand status based on DDVAP challenge in 2017; she has had symptoms of easy bruising and hypermenorrhea.

Given the similarity of her neuropsychiatric and joint symptoms to autoinflammatory syndrome and her lack of responses to TNF-α inhibitors, infliximab was discontinued. Then, 10 weeks after, anakinra, an IL-1β blocker, was started (100 mg/day). Supplemental Ig was also discontinued secondary to her severe adverse reactions. She revealed marked improvement of her clinical symptoms (headache, fatigue, joint ache, sleep disturbance, and symptoms resembling postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS)) over 2–3 months after starting anakinra SQ injection. However, her POTS symptoms were not completely resolved. Five months after starting anakinra, she had recurrence of mild diarrhea that resolved with a 10-day course of metronidazole, although microbial workup was negative. Then, 12 months after discontinuation of infliximab, the GI symptoms due to Yersinia enterocolitis occurred, which led to the recurrence of CD lesions. Thus, 5 months after onset of Yersinia enterocolitis, treatment with ustekinumab (45 mg SQ injection x2, 4 weeks apart, then every 12 weeks) was initiated, and remission of CD was achieved in 6 months. Anakinra was discontinued after remission was achieved.

Laboratory findings

Two AD variants of NLRP12 and IRF2BP2 are expected to alter cytokine production by monocyte–macrophage lineage cells [9,10,11]. Therefore, cytokine production by purified peripheral blood monocytes (PBMo) with methodologies reported elsewhere [12] was determined at two time points: prior to starting anakinra, which was 2 months after discontinuation of infliximab, and then 5 months after starting anakinra.

The results of these assays revealed a decrease in the production of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in response to candida heat extract as a source of β-glucan, which activates the inflammasome pathway [12]. There was no increase in spontaneous production of cytokines at two time points. Production of counterregulatory cytokines (IL-10, sTNFRII, or TGF-β) in response to β-glucan did not differ after starting anakinra (Fig. 1). Such changes were not observed in PBMo cytokine production in response to TLR agonists (LPS, zymosan, and CL097). Production of IL-1β and TNF-α was evaluated after initiation of usterkinumab treatment, following the initial submission of this manuscript. They remained within normal limits.

Discussion

Progress in genetic analysis has made it possible to evaluate the effects of variants of genotypes on both the clinical manifestation and therapeutic responses of autoimmune diseases. Risk variants of genes have been implicated in the onset and progression of IBD, in close association to interactions with gut microbiota [13]. The presented case illustrates complex gene–gene interactions in association with IBD and the utility of WES for assessing atypical clinical manifestation of IBD.

NLRP12 has emerged as a crucial regulator of innate immunity, and the presence of NLRP12 variants is expected to increase the risk of GI inflammation by affecting gut immune homeostasis. In rodent models, NLRP12 is reported to promote bacterial tolerance, augmenting the diversity of microbe and gut immune homeostasis [3]. This is partly due to proteasomal degradation of NOD2 by NLRP12 [10]. NLRP12 is also known to exert a broad range of regulatory actions on major activation signaling pathways (NF-kB, NFAT, MAPK, and mTOR pathways) [14]. As a result, the presence of NLRP12 variants is expected to result in increased production of inflammatory cytokines, which include IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. In IBD patients, increase in serum levels of TNF-α is associated with the NLRP12 variant (rs34436714) [4]. In two CAPS patients, with the same NLRP12 variant that was found in the presented case, increase in spontaneous production of TNF-α and IL-1β has been reported [9]. Therefore, presence of the NLRP12 variant in the presented case is expected to be a predisposing factor for developing IBD.

The increased production of inflammatory cytokines, discussed above, is also expected to affect the central nervous system. It is well known that patients with dysregulated cytokine production of IL-1β as seen in autoinflammatory syndromes are known to exhibit neuropsychiatric symptoms [15]. Increase in inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) has also be reported in common neuropsychiatric conditions including depression and schizophrenia [16]. It is of note that the presented case was initially diagnosed with PANS due to predominant anxiety symptoms, although she did not reveal other symptoms typically seen in PANS (tics, changes in fine motor functions, etc.). Increase in these inflammatory cytokines and the resultant symptoms can be controlled with OCS. In fact, in the presented case, initially, she responded well to pulse OCS for controlling anxiety.

WES analysis revealed that she had an AD GOF variant of IRF2BP2. IRFBP2 exerts regulatory functions on multiple lineage cells, by serving as a transcriptional co-repressor [17,18,19]. These actions of IRF2BP2 on monocyte–macrophage lineage cells suppress the differentiation of inflammatory type 1 (M1) macrophages, attenuating inflammation [11, 20]. Repressive actions of IRF2BP2 have been shown to attenuate atherosclerosis and CN inflammation, partly suppressing production of inflammatory cytokines [11, 20]. However, excessive suppression through IRF2BP2 can be harmful. It was shown that an AD GOF mutation of IRF2BP2 was implicated in a familial form of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) [7]. In the reported CVID cases with the IRF2BP2 mutation, excessive IRF2BP2 actions impaired terminal differentiation of B lineage cells [7].

The presented case paternally inherited AD variants of both NLRP12 and IRF2BP2. A LOF AD variant of NLRP12 is expected to augment production of inflammatory cytokines and disrupt gut immune homeostasis, while the AD GOF variant of IRF2BP2 suppresses activation signals of multiple lineage cells. We hypothesized that the presence of the AD NLRP12 variant predisposed her to CD and neuropsychiatric symptoms following immune insults. Development of hypogammaglobulinemia may have been associated with the AD GOF IRF2BP2 variant. Antagonistic actions of these two variants (IRF2BP2 and NLRP12) may have provided the relatively stable condition seen during treatment with monthly IVIg, which likely attenuated immune insults from microbial infection. However, the development of CD and subsequent treatment with TNF-α inhibitors may have augmented the effects of the NLRP12 variant on inflammasomes, leading to clinical features resembling autoinflammatory syndromes. Lack of recurrent fever and skin symptoms may have been associated with the GOF IRF2BP2 variant. Once CD reached remission, we hypothesized that a low dose of anakinra (100 mg/day) may have helped restore balance to her inflammatory responses. Indeed, she revealed marked improvement of her clinical symptoms with anakinra. In two patients with the same NLRP12 variant as found in the presented case, anakinra treatment caused increase in TNF-α production within 3–4 months [9]. However, in the presented case, anakinra treatment did not cause an increase in TNF-α production (Fig 1). In fact, this patient did not reveal an increase in spontaneous production of TNF-α or IL-1β. This may be due to the presence of the GOF IRF2BP2 variant. However, following immune insults, she may require additional anti-inflammatory medications to control TNF-α-mediated inflammation. This became apparent when she experienced recurrence of CD lesions following Yersinia enterocolitis. Treatment with ustekinumab was successful for controlling her recurrent CD lesions and led to the subsequent discontinuation of anakinra. This may be due to the fact that ustekinumab, a monocloncal antibody against IL-12p40, which blocks signaling pathways of IL-12 and IL-23, can successfully block IL-1β-mediated Th17 cell activation as well as TNF-α-induced Th1 activation [21, 22].

However, her fluctuating neuropsychiatric symptoms may also be affected by other factors. For example, the presence of maternal diabetes and use of steroids can worsen the manifestation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Crohn’s disease [23, 24], although her mother denied history of gestational diabetes during her pregnancy.

Conclusions

The revelation of two AD GOF gene variants by WES provided a better understanding of the atypical clinical features and failed responses to TNF-α inhibitors in the presented case. In IBD cases with puzzling clinical features and suboptimal responses to first.line therapeutic measures, genetic workup using WES may be helpful. In addition, her atypical course of CD emphasizes the importance of endoscopic biopsies for diagnosis and follow-up.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Autosomal dominant

- CAPS:

-

Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome

- CD:

-

Crohn’s disease

- CVID:

-

Common variable immunodeficiency

- GOF:

-

Gain of function

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- Ig:

-

Immunoglobulin

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IVIg:

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- LOF:

-

Loss of function

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- NLR:

-

NOD-like receptor

- OCS:

-

Oral corticosteroids

- PANS:

-

Pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome

- PBMo:

-

Peripheral blood monocytes

- SQ:

-

Subcutaneous

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- WES:

-

Whole-exome sequencing

References

Prochnicki T, Latz E. Inflammasomes on the crossroads of innate immune recognition and metabolic control. Cell Metab. 2017;26(1):71–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.018.

Shen M, Tang L, Shi X, Zeng X, Yao Q. NLRP12 autoinflammatory disease: a Chinese case series and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36(7):1661–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3410-y.

Chen L, Wilson JE, Koenigsknecht MJ, Chou WC, Montgomery SA, Truax AD, Brickey WJ, Packey CD, Maharshak N, Matsushima GK, et al. NLRP12 attenuates colon inflammation by maintaining colonic microbial diversity and promoting protective commensal bacterial growth. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(5):541–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/ni.3690.

Dellaporta E, Lazaridis LD, Koussoulas V, Netea MG, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Triantafyllou K. Association between genotypes of rs34436714 of NLRP12 and serum tumor necrosis factor-alpha in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(23): e15913. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000015913.

Tal Y, Ribak Y, Khalaila A, Shamriz O, Marcus N, Zinger A, Meiner V, Schuster R, Lewis EC, Nahum A. Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) variant and NLRP12 mutation confer susceptibility to a complex clinical presentation. Clin Immunol. 2020;212: 108249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2019.108249.

Ledesma PA, Guerra JC, Burbano M, Procel P, Pedroza LA. Whole exome sequencing in a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, optic neuritis, and periodic fever syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2019;13(1):368. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2305-3.

Keller MD, Pandey R, Li D, Glessner J, Tian L, Henrickson SE, Chinn IK, Monaco-Shawver L, Heimall J, Hou C, et al. Mutation in IRF2BP2 is responsible for a familial form of common variable immunodeficiency disorder. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):544-550 e544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.018.

Jeru I, Le Borgne G, Cochet E, Hayrapetyan H, Duquesnoy P, Grateau G, Morali A, Sarkisian T, Amselem S. Identification and functional consequences of a recurrent NLRP12 missense mutation in periodic fever syndromes. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(5):1459–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30241.

Jeru I, Hentgen V, Normand S, Duquesnoy P, Cochet E, Delwail A, Grateau G, Marlin S, Amselem S, Lecron JC. Role of interleukin-1beta in NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorders and resistance to anti-interleukin-1 therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(7):2142–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30378.

Normand S, Waldschmitt N, Neerincx A, Martinez-Torres RJ, Chauvin C, Couturier-Maillard A, Boulard O, Cobret L, Awad F, Huot L, et al. Proteasomal degradation of NOD2 by NLRP12 in monocytes promotes bacterial tolerance and colonization by enteropathogens. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5338. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07750-5.

Chen HH, Keyhanian K, Zhou X, Vilmundarson RO, Almontashiri NA, Cruz SA, Pandey NR, Lerma Yap N, Ho T, Stewart CA, et al. IRF2BP2 reduces macrophage inflammation and susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117(8):671–83. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305777.

Jyonouchi H, Geng L. Associations between monocyte and T cell cytokine profiles in autism spectrum disorders: effects of dysregulated innate immune responses on adaptive responses to recall antigens in a subset of ASD children. Int J Mol Sci. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20194731.

Chu H, Khosravi A, Kusumawardhani IP, Kwon AH, Vasconcelos AC, Cunha LD, Mayer AE, Shen Y, Wu WL, Kambal A, et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science. 2016;352(6289):1116–20. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aad9948.

Gharagozloo M, Mahmoud S, Simard C, Mahvelati TM, Amrani A, Gris D. The dual immunoregulatory function of Nlrp12 in T cell-mediated immune response: lessons from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cells. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells7090119.

Keddie S, Parker T, Lachmann HJ, Ginsberg L. Cryopyrin-associated periodic fever syndrome and the nervous system. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2018;20(10):43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-018-0526-1.

Morris G, Puri BK, Walker AJ, Maes M, Carvalho AF, Bortolasci CC, Walder K, Berk M. Shared pathways for neuroprogression and somatoprogression in neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;107:862–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.09.025.

Secca C, Faget DV, Hanschke SC, Carneiro MS, Bonamino MH, de-Araujo-Souza PS, Viola JP. IRF2BP2 transcriptional repressor restrains naive CD4 T cell activation and clonal expansion induced by TCR triggering. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(5):1081–91. https://doi.org/10.1189/jlb.2A0815-368R.

Manjur A, Lempiainen JK, Malinen M, Palvimo JJ, Niskanen EA. IRF2BP2 modulates the crosstalk between glucocorticoid and TNF signaling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;192: 105382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105382.

Lempiainen JK, Niskanen EA, Vuoti KM, Lampinen RE, Goos H, Varjosalo M, Palvimo JJ. Agonist-specific protein interactomes of glucocorticoid and androgen receptor as revealed by proximity mapping. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2017;16(8):1462–74. https://doi.org/10.1074/mcp.M117.067488.

Cruz SA, Hari A, Qin Z, Couture P, Huang H, Lagace DC, Stewart AFR, Chen HH. Loss of IRF2BP2 in microglia increases inflammation and functional deficits after focal ischemic brain injury. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017;11:201. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2017.00201.

Hashash JG, Mourad FH. Positioning biologics in the management of moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(4):351–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOG.0000000000000735.

Noviello D, Mager R, Roda G, Borroni RG, Fiorino G, Vetrano S. The IL23-IL17 immune axis in the treatment of ulcerative colitis: successes, defeats, and ongoing challenges. Front Immunol. 2021;12: 611256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.611256.

Lee KW, Ching SM, Devaraj NK, Chong SC, Lim SY, Loh HC, Abdul Hamid H. Diabetes in pregnancy and risk of antepartum depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113767.

Devaraj NK. A recurrent cutaneous eruption. BMJ Case Rep. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-228355.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patient and her family for allowing us to present this case. A part of this study was funded from individual donation to the pediatric immunology research fund, Saint Peter’s Foundation, New Brunswick, NJ.

Funding

This study is supported partly by funding from the Jonty Foundation, St. Paul, MN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HJ was responsible for preparing most of the manuscript, including the clinical course and data analysis. GL was responsible for cytokine assays before and after anakinra treatment and analysis of laboratory results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is waived at our institution, per our policy of the institutional review board.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient, who was 19 years of age at the time of consent obtainment, for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

There are no financial or nonfinancial competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Jyonouchi, H., Geng, L. Whole-exome sequencing in a subject with fluctuating neuropsychiatric symptoms, immunoglobulin G1 deficiency, and subsequent development of Crohn’s disease: a case report. J Med Case Reports 16, 187 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03404-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03404-9