Abstract

Background

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is generally preceded by an infection, and it is usually self-limiting and non-recurrent. However, when there are multiple attacks of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis followed by optic neuritis, it is defined as acute disseminated encephalomyelitis-optic neuritis. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and optic neuritis preceded by autoinflammation, triggered by periodic fever syndrome.

Case summary

We report on a case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis with optic neuritis and periodic fever syndrome in a 12-year-old Ecuadorian Hispanic boy with several relapses over the past 10 years, always preceded by autoinflammatory manifestations and without evidence of infectious processes. Whole exome sequencing was performed, and although the results were not conclusive, we found variants in genes associated with both autoinflammatory (NLRP12) and neurological (POLR3A) phenotypes that could be related to the disease pathogenesis having a polygenic rather than monogenic trait.

Conclusion

We propose that an autoinflammatory basis should be pursued in patients diagnosed as having acute disseminated encephalomyelitis and no record of infections. Also, we show that our patient had a good response after 1 year of treatment with low doses of intravenous immunoglobulin and colchicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) are autoinflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system (CNS). One of the main differences between these two entities is the chronicity and progressive neurological disability in MS, while ADEM is self-limiting, non-recurrent, and rarely produces neurological disabilities [1]. However, when there are multiple ADEM attacks followed by optic neuritis (ON), it is defined as ADEM-ON [2]. It is widely known that the clinical presentation of ADEM is an inflammatory process, and it is preceded by vaccination or infections. However, some cases are secondary to a fever of unknown origin [3, 4], which raises the question if a periodic fever syndromes (PFS) could be the recurrent trigger of the CNS inflammatory process in ADEM-ON as has been previously reported in MS [5]. NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorder (NLRP12AD) is a type 2 familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS2), and part of the PFS [6,7,8,9]. It is an immune-mediated disease characterized by the presence of recurrent fever (of unknown origin) and other autoinflammatory features such as mouth ulcers and headaches [10]. Here, we describe a patient diagnosed as having ADEM-ON who also presented with familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome (FCAS) for whom we used whole exome sequencing (WES) to dissect possible variants in a non-HLA set of genes that could explain the patient’s clinical features (immunological and neurological).

Case presentation

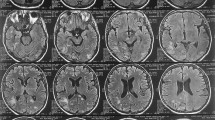

Our patient is a 12-year-old Ecuadorian Hispanic boy from unrelated Hispanic parents; he presented to the pediatric department of the “Hospital de los Valles” with mouth ulcers, bilateral vision loss, headache, fever, lethargy, ataxia, dizziness, and left-sided hemiparesis. A clinical examination did not reveal any identifiable cause of fever. His familial history was unremarkable except for his maternal grandfather, who had type II diabetes mellitus. Our patient’s past medical history revealed a 10-year history of several episodes of pharyngitis, mouth ulcers, headaches, dizziness, fevers of unknown origin, and tonsillitis. These symptoms commonly preceded the appearance of neurological symptoms such as delayed speech, hypotonia, vision loss, ataxia, lethargy, and left hemiparesis. This pattern had been consistent and often required hospitalization for the treatment of neurological manifestations. The treatment consisted of corticoid therapy, which offered rapid improvement. Moreover, he has significant endocrine features, including small stature, delayed bone age, obesity, small hands, and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Although Prader–Willi syndrome was suspected, genetic analysis ruled this out. Ophthalmological imaging studies at his first hospitalization 10 years ago were consistent with a demyelinating and axonal lesion of the left optic tract, which is compatible with ON. In addition, C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammatory index, was elevated at every hospitalization. The following laboratory studies, which were carried out on several occasions, had results within the normal range: complete blood count (CBC); serum chemistry; urine and blood culture; strep test; throat swab; serology for cytomegalovirus, (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex viruses (HSV), rubella, and toxoplasmosis; immunologic screening for antinuclear antibodies, rheumatologic factor, immunoglobulin A (IgA) and immunoglobulin M (IgM) antiphospholipids; thyroid hormones; cortisol; and insulin. He also underwent the following examinations: chest and abdominal X-rays which were normal; pathergy test which was negative; brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies including fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) T2 sequences which showed multiple hyperintense lesions throughout the years (Fig. 1); spinal cord MRI studies that did not disclose any lesion; and cerebrospinal fluid analyses which were consistently normal with negative oligoclonal bands. MS was ruled out because he did not meet the McDonald diagnostic criteria for this disease. In addition, anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), anti-aquaporin 4 (AQP4), and anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) were ordered but failed to disclose the diagnosis. Anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) was ordered, and the titer was 1:80 (considered negative); however, he was in treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) at the time of the anti-MOG evaluation. Given the unusual phenotype, we decided to perform a WES via a commercial service offered by the Baylor Miraca Genetics Laboratories. A list of variants potentially associated with the neurologic and immune features of our patient are listed in Table 1. A WES was not performed on his parents due to financial reasons. Even though the results were not conclusive, we found variants in genes associated with both autoinflammatory (NLRP12) and neurological (POLR3A) phenotypes that could be related to the disease pathogenesis being a polygenic rather than monogenic trait.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery T2 sequences showing multiple hyperintense lesions through the years. a 2008: Multiple injuries, mainly subcortical in temporal and occipitotemporal gyrus, and in the white matter of the corona radiata and semioval center. Lesions are enhanced after contrast. b 2010: Frontal subcortical injuries. Periatrial and parahippocampal lesions. There is a persistence of white matter lesions, and there are new infratentorial lesions. c 2011: Persistence of the periatrial lesions and left midbrain lesion. d 2013: Persistence of periatrial lesions and two small and new lesions in the basal ganglia infratentorial lesions. e 2014: New appearance of lesions in the cortex. Frontal and right superior temporal subcortical lesions. Right periatrial lesion has increased in size, reaching the cortex, parietal and occipital gyrus and corona radiata. f 2015: Persistence of periatrial lesions. There are smaller lesions in the white matter of the middle and lower right temporal gyrus and the semioval center. g 2017: After 7 months with intravenous immunoglobulin treatment – same lesions as the last magnetic resonance imaging in 2015. No new changes

A final diagnosis of ADEM-ON and NLRP12AD was established. For the past year, our patient has remained on a monthly therapy with IVIG 500 mg/kg and orally administered colchicine (0.5 mg daily). With this treatment, he has remained free of new autoinflammatory and neurological episodes and has not required corticoids. An MRI study performed 7 months after the start of IVIG and colchicine showed an absence of new lesions.

Discussion

ADEM is considered an autoinflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS and is often secondary to infections [1]. However, some cases have been associated with recurrent inflammation and absence of known infections [3, 4], raising the question if autoinflammation could trigger CNS demyelination as has been previously reported in MS [5]. It could be expected to be of genetic origin – probably with a monogenic basis – based on the common origin of both diseases (that is, autoinflammation and ADEM-ON) and the early onset of manifestations. Although none of the variants can be considered to be the sole cause of the disease, we hypothesize that the presence of polymorphisms in NLRP12 and SIAE (Table 1) trigger systemic autoinflammation, and such inflammation could influence the demyelination process in an unknown fashion. NLRP12AD, part of the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS), has been associated with several autoinflammatory conditions that are similar to the immunological features of our patient [9,10,11,12]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no cases of NLRP12AD and inflammatory diseases in the CNS of humans. Interestingly, the role of NLRP12 in inflammasome activation in the brain of murine models, including a model of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, has been recently described [13,14,15]. In addition, SIAE has also been associated with susceptibility to autoimmune diseases [16]. However, this association has been questioned [17]. Although we failed to find a candidate gene or a genetic link with the neurological manifestations, the variant in POLR3A is important because bi-allelic mutations on this gene are associated with hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 7 (HLD7) [18]. Interestingly, our patient presents hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, which is one of the hallmarks of HLD7; however, the other clinical features and the MRI pattern are barely compatible with HLD7. Although only one of the POLR3A alleles is mutated, a new association between heterozygous mutations in POLR3A and susceptibility to varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection (including encephalitis) was described recently. However, our patient did not show any evidence of VZV infection. Furthermore, these cases presented incomplete penetrance in healthy carriers [19]. Thus, we cannot rule out a possible influence of the POLR3A in the clinical features presented by our patient. High doses of IVIG are broadly used for the treatment of autoimmune diseases of different etiologies, including ADEM [20]. However, the use of low doses of IVIG in ADEM-ON has not been extensively documented. Recently, a cohort of patients with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis (MDEM), of whom some received monthly IVIG treatment, was described [21]. These patients showed improved clinical manifestations, similar to our case. Our patient has had recurrent autoinflammatory symptoms leading to neurologic episodes every 6 months on average. Since the treatment with low-dose IVIG and colchicine was started, he has not presented any autoinflammatory or neurologic symptoms. It is known that IVIG at high doses works as an immunosuppressant to treat several autoimmune diseases. This effect is probably mediated by scavenging of complement and blockade or modulation of Fc receptors. At low doses, it is used as a prophylactic treatment in patients with immunodeficiencies in part by neutralizing the antigens. This could be a possibility in this patient because it could be neutralizing the virus or antigens. Therefore, this treatment prevents potential infections that usually trigger the autoinflammation and neurological manifestations, as is broadly known in ADEM or MDEM [1]. In any of these two scenarios, the IVIG and colchicine are preventing the inflammation that precedes the neurological manifestations. Typically, FCAS is treated with interleukin-1 (IL-1) inhibitors such as anakinra, rilonacept, or canakinumab [22, 23]. However, given the difficulty of finding these drugs in Ecuador and our patient’s economic inability to acquire them, colchicine was prescribed. This medication has a widespread effect on autoinflammatory disorders and has been widely accepted as a treatment in other PFS, such as in familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) [22]. Apart from some minor gastrointestinal side effects, the medication has been well tolerated by our patient, and he has not presented any autoinflammatory or neurological symptoms.

Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disease with neurological manifestations. We suggest that patients with ADEM-ON should be evaluated for autoinflammation (including variants in NLRP12) in the absence of documented infections.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ADEM:

-

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis

- ADEM-ON:

-

Multiple acute disseminated encephalomyelitis attacks followed by optic neuritis

- AQP4:

-

Aquaporin 4

- CAPS:

-

Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes

- CBC:

-

Complete blood count

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- EBV:

-

Epstein–Barr virus

- FCAS:

-

Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome

- FCAS2:

-

Type 2 familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome

- FLAIR:

-

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FMF:

-

Familial Mediterranean fever

- HLD7:

-

Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 7

- HSV:

-

Herpes simplex viruses

- IgA:

-

Immunoglobulin A

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- IL-1:

-

Interleukin-1

- IVIG:

-

Intravenous immunoglobulin

- MAG:

-

Myelin-associated glycoprotein

- MBP:

-

Myelin basic protein

- MDEM:

-

Multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis

- MOG:

-

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- NLRP12AD:

-

NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorder

- ON:

-

Optic neuritis

- PFS:

-

Periodic fever syndromes

- VZV:

-

Varicella-zoster virus

- WES:

-

Whole exome sequencing

References

Esposito S, Di Pietro GM, Madini B, et al. A spectrum of inflammation and demyelination in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) of children. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14:923–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2015.06.002.

Pohl D, Alper G, Van Haren K, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, Updates on an Inflammatory CNS syndrome. Neurology. 2016;87:38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-53088-0.00018-X.

Ching BH, Mohamed AR, Khoo TB, et al. Multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis followed by optic neuritis in a child with gluten sensitivity. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1209–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458515593404.

Costanzo MD, Camarca ME, Colella MG, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis presenting as fever of unknown origin: case report. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-103.

Schuh E, Lohse P, Ertl-Wagner B, et al. Expanding spectrum of neurologic manifestations in patients with NLRP3 low-penetrance mutations. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2015;2:e109. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000109.

Jéru I, Duquesnoy P, Fernandes-Alnemri T, et al. Mutations in NALP12 cause hereditary periodic fever syndromes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105(5):1614–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0708616105.

Volpe G, Mauro A, Mellos A. NLRP12-associated autoinflammatory disorder: case report. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2014;12(Suppl 1):P262. https://doi.org/10.1186/1546-0096-12-S1-P262.

Borghini S, Tassi S, Chiesa S, et al. Clinical Presentation and Pathogenesis of Cold-Induced Autoinflammatory Disease in a Family With Recurrence of an NLRP12 Mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(3):830–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30170.

Xia X, Dai C, Zhu X, Liao Q, et al. Identification of a Novel NLRP12 Nonsense Mutation (Trp408X) in the Extremely Rare Disease FCAS by Exome Sequencing. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156981. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0156981.

Caso F, Rigante D, Vitale A, et al. Monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes: state of the art on genetic, clinical, and therapeutic issues. Int J Rheumatol. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/513782.

De Pieri C, Vuch J, De Martino E, et al. Genetic profiling of autoinflammatory disorders in patients with periodic fever: a prospective study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2015;13:11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-015-0006-z.

Shen M, Tang L, Shi X, Zeng X, Yao Q. NLRP12 autoinflammatory disease: a Chinese case series and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2017;36:1661–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3410-y.

Nagyőszi P, Nyúl-Tóth Á, Fazakas C, Wilhelm I, Kozma M, Molnár J, Haskó J, Krizbai IA. Regulation of NOD-like receptors and inflammasome activation in cerebral endothelial cells. J Neurochem. 2015;135:551–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.

Chang SL, Huang W, Mao X, Sarkar S. NLRP12 Inflammasome Expression in the Rat Brain in Response to LPS during Morphine Tolerance. Brain Sci. 2017;7 https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci7020014.

Gharagozloo M, Mahvelati TM, Imbeault E, Gris P, Zerif E, Bobbala D, Ilangumaran S, Amrani A, Gris D. The nod-like receptor, Nlrp12, plays an anti-inflammatory role in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroinflammation. 2015;12:198. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-015-0414-5.

Surolia I, Pirnie SP, Chellappa V, Taylor KN, Cariappa A, Moya J, Liu H, Bell DW, Driscoll DR, Diederichs S, Haider K, Netravali I, Le S, Elia R, Dow E, Lee A, Freudenberg J, De Jager PL, Chretien Y, Varki A, MacDonald ME, Gillis T, Behrens TW, Bloch D, Collier D, Korzenik J, Podolsky DK, Hafler D, Murali M, Sands B, Stone JH, Gregersen PK, Pillai S. Functionally defective germline variants of sialic acid acetylesterase in autoimmunity. Nature. 2010;466:243–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09115.

Hunt KA, Smyth DJ, Balschun T, et al. Rare and functional SIAE variants are not associated with autoimmune disease risk in up to 66,924 individuals of European ancestry. Nat Genet. 2011;44:3–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.1037.

Wolf NI, Vanderver A, van Spaendonk RM, Schiffmann R, Brais B, Bugiani M, Sistermans E, Catsman-Berrevoets C, Kros JM, Pinto PS, Pohl D, Tirupathi S, Strømme P, de Grauw T, Fribourg S, Demos M, Pizzino A, Naidu S, Guerrero K, van der Knaap MS, Bernard G, 4H Research Group. Clinical spectrum of 4H leukodystrophy caused by POLR3A and POLR3B mutations. Neurology. 2014;83:1898–905. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001002.

Ogunjimi B, Zhang SY, Sørensen KB, Skipper KA, Carter-Timofte M, Kerner G, Luecke S, Prabakaran T, Cai Y, Meester J, Bartholomeus E, Bolar NA, Vandeweyer G, Claes C, Sillis Y, Lorenzo L, Fiorenza RA, Boucherit S, Dielman C, Heynderickx S, Elias G, Kurotova A, Auwera AV, Verstraete L, Lagae L, Verhelst H, Jansen A, Ramet J, Suls A, Smits E, Ceulemans B, Van Laer L, Plat Wilson G, Kreth J, Picard C, Von Bernuth H, Fluss J, Chabrier S, Abel L, Mortier G, Fribourg S, Mikkelsen JG, Casanova JL, Paludan SR, Mogensen TH. Inborn errors in RNA polymerase III underlie severe varicella zoster virus infections. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3543–56. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI92280.

Gadian J, Kirk E, Holliday K, Lim M, Absoud M. Systematic review of immunoglobulin use in pediatric neurological and neurodevelopmental disorders. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:136–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.13349.

Baumann M, Hennes EM, Schanda K, Karenfort M, Kornek B, Seidl R, Diepold K, Lauffer H, Marquardt I, Strautmanis J, Syrbe S, Vieker S, Höftberger R, Reindl M, Rostásy K. Children with multiphasic disseminated encephalomyelitis and antibodies to the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG): Extending the spectrum of MOG antibody positive diseases. Mult Scler. 2016;22:1821–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516631038.

Hoffman HM. Therapy of autoinflammatory syndromes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1129–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.001.

Haar N, Lachmann H, Özen S, et al. Treatment of autoinflammatory diseases: results from the Eurofever Registry and a literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(5):678–85. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201268.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marcela Bovera for assistance in the clinical data collection and Dr Kevin Rostasy for the anti-MOG evaluation.

Funding

No funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the work: PAL and LAP. Clinical data collection: PAL, JCG, MB, and PP. Imaging data collection and analysis: PAL, JCG, and LAP. Genomic data analysis: LAP. Laboratory data collection and analysis: PAL and LAP. Drafting the article: PAL and LAP. Critical revision of the article: PAL, JCG, MB, PP, and LAP. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: PAL, JCG, MB, PP, and LAP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

PAL: Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. Previously: Instructor at Universidad San Francisco de Quito Medical School.

LAP: Professor of Immunology and Genetics, Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Adjunct Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine.

JCG: Professor of Radiology, Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Head of Radiology, Hospital de los Valles (Quito, Ecuador).

MB: Pediatric Endocrinologist, Hospital de los Valles (Quito, Ecuador).

PP: Pediatric Neurologist, Hospital de los Valles (Quito, Ecuador).

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Institutional Review Board from the Universidad San Francisco de Quito with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board from the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, with the protocol number: 2015-061 T.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s legal guardians for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ledesma, P.A., Guerra, J.C., Burbano, M. et al. Whole exome sequencing in a child with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, optic neuritis, and periodic fever syndrome: a case report. J Med Case Reports 13, 368 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2305-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-019-2305-3