Abstract

Background

Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus is a known pathogen that causes infective endocarditis, and most cases involve the left heart valves. We present the first reported case of prosthetic tricuspid valve endocarditis caused by this microorganism. Relevant literature is reviewed.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old Jewish female with a history of a prosthetic tricuspid valve replacement was admitted to the emergency department because of nonspecific complaints including effort dyspnea, fatigue, and a single episode of transient visual loss and fever. No significant physical findings were observed. Laboratory examinations revealed microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and a few nonspecific abnormalities. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated a vegetation attached to the prosthetic tricuspid valve. The involved tricuspid valve was replaced by a new tissue valve, and Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus was grown from its culture. Prolonged antibiotic treatment was initiated.

Conclusions

Based on this report and the reviewed literature, Streptococcus gallolyticus should be considered as a rare but potential causative microorganism in prosthetic right-sided valves endocarditis. The patient’s atypical presentation emphasizes the need for a high index of suspicion for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infective endocarditis (IE) is defined as an infection of the endocardial surface of the heart, and most commonly involves the heart valves. Less commonly, ventricular septal defect, mural endocardium, or intracardiac devices may also be involved. Right-sided endocarditis accounts for 5–10% of IE cases, and is strongly associated with intravenous drug abusers (IVDA) [1]. Most cases involve the tricuspid valve, and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is the most common pathogen [1, 2]. Unlike left-sided IE, isolated right-sided IE is not associated with peripheral embolic and vascular manifestations, unless there is an intracardiac shunt. Pulmonary findings, such as lung abscesses, may be present [3].

Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus (S. gallolyticus), formerly Streptococcus bovis biotype 1, is part of the Streptococcus bovis (S. bovis) complex, which is responsible for 2–10% of IE cases [2]. IE associated with the S. bovis complex most commonly involves the aortic valve, the mitral valve, or both. Involvement of the tricuspid valve or pacemaker electrode is very rare [2, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. In this report, we use the name S. bovis to discuss the results of studies that did not relate to the specific subspecies of that complex.

We present here an atypical case of S. gallolyticus infection of a prosthetic tricuspid valve and a pacemaker electrode in a non-IVDA woman.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old Jewish female was admitted to our hospital because of worsening effort dyspnea and cough, extreme fatigue, and functional decline. Her complaints began 2 months prior to admission, following a single episode of fever (38 °C), transient bilateral loss of sight, and vomiting. Her medical history includes a bioprosthetic tricuspid valve implantation 4 years prior to the current hospitalization due to tricuspid stenosis, followed by a pacemaker implantation due to periprocedural complete heart block. Her regular medical therapy includes allopurinol (100 mg per day), bisoprolol (2.5 mg per day), apixaban (2.5 mg twice a day), and vitamin D3 (1000 international units per day). The patient had not undergone recent medical procedures (including dental care) and had no history of intravenous drug use.

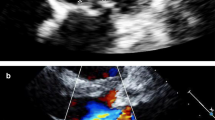

At the time of her admission, the patient was alert and afebrile, and presented normal vital signs. Physical examination demonstrated no significant findings, without peripheral stigmata of endocarditis, heart murmurs, or neurological deficits. Initial laboratory tests revealed mild hemolytic anemia [decrease in hemoglobin from a recent level of 14.9 g/dL to 12.2 g/dL, increased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels up to 1080 U/L, and mild indirect hyperbilirubinemia], in addition to the presence of schistocytes in the peripheral blood smear. Additional abnormal laboratory results included increased levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and an elevation of cholestatic liver enzymes. Urinalysis demonstrated hematuria and mild proteinuria, without clinical or laboratory findings of acute kidney injury. A mildly elevated level of rheumatoid factor was noted. Chest X-ray and fundoscopy revealed no pathological findings. Transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated a 1.1 cm vegetation on the tricuspid valve. Transesophageal echocardiogram demonstrated severe tricuspid stenosis as a complication of the attached vegetation, as well as an additional 1.1 cm vegetation on the pacemaker electrode (Fig. 1). Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography–computed tomography (FDG PET-CT) demonstrated pathological rectal uptake, suggestive of a neoplastic process. No septic pulmonary emboli were observed. During the first 2 days of hospitalization, a total of five blood culture sets were positive for S. gallolyticus, and susceptible for beta-lactam antibiotics as well as for clindamycin, erythromycin, and vancomycin. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for penicillin and ampicillin was 0.094 µg/mL. Intravenous therapy with ceftriaxone was initiated, according to the antibiotic sensitivity profile of the pathogen.

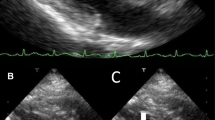

On day 11 after admission, open-heart surgery was performed. The involved tricuspid valve was replaced (Fig. 2) by a tissue valve (Mosaic 27 by Medtronic). The infected pacemaker electrodes were removed and replaced by temporary, and later permanent, epicardial electrodes. The intraoperative and postoperative course was uneventful. Positive growth of S. gallolyticus was obtained from both the removed valve and electrodes. The patient was treated with 2 g of ceftriaxone for an additional 6 weeks. After a rehabilitation process in our hospital, the patient was discharged for further ambulatory follow-up, including endoscopic evaluation of the rectal lesion mentioned above. To the best of our knowledge, the patient refused to undergo this evaluation because of personal reasons. Three years after her discharge, the patient is clinically stable, with no clinical or laboratory findings that raise suspicion of rectal malignancy.

Discussion and conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of S. bovis IE on a prosthetic tricuspid valve. Table 1 summarizes an extensive literature review including 16 studies and a total of 500 cases of S. bovis IE. In these studies, S. bovis was responsible for about 10% of the total IE cases. The vast majority of cases involved native valves (87%). A native aortic valve was the most prevalent site of infection (28%), followed by a coinfection of native aortic and mitral valves (18%). An isolated infection of a native mitral valve was reported in 16% of the cases and a native tricuspid valve infection in only 2%. Prosthetic tricuspid valve involvement has not been reported in any of the cases, or in any other case report. Furthermore, infection of pacemaker electrodes was also extremely rare, with only two reports in the reviewed studies (0.4%) and a few case reports.

Streptococcus gallolyticus infections are also associated with colonic neoplasms. A recent study from a multicenter registry found colorectal tumors in 69% of S. bovis IE patients, with a clear predominance of benign lesions (78%) [24]. Among the four subspecies of the S. bovis complex, S. gallolyticus has the strongest association with colonic neoplasm, and this association is higher for IE compared with other sites of S. gallolyticus infection [25]. Therefore, gastrointestinal endoscopy may be advisable as routine screening for occult gastrointestinal lesions in patients with S. bovis bacteremia.

A history of prosthetic heart valve implantation constitutes a significant risk factor for IE, with the greatest risk during the first 6–12 months after the valve replacement. Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE) accounts for 7–25% of IE cases in developed countries, with a similar risk for bioprosthetic and mechanical valves at 5 years after the valve replacement [3]. Antecedent native valve IE, implantation of multiple valves, male sex, and older age were reported as risk factors for PVE [4,5,6].

As mentioned before, S. aureus is the most common pathogen causing tricuspid IE, a disease that primarily affects IVDA [1]. Besides IVDA, right-sided IE can also occur in patients with intracardiac devices (such as a pacemaker electrode), as in this case. In 2016, the European Society of Cardiology reported a threefold increase in the incidence of pacemaker IE among non-IVDA over the past 26 years. According to the study, pacemaker IE represented 6.1% of all IE cases, and most of the affected patients were males (80%), without a history of underlying structural heart disease (92%) or previous IE. The common pathogens were staphylococci and enterococci (84% and 12%, respectively). No cases of S. bovis pacemaker IE were observed [26]. In another large multicenter prospective cohort study, S. bovis was found in only 3% of patients with IE involving intracardiac electronic devices (including pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators) [2].

IE is a complex infectious disease characterized by a highly variable clinical presentation, heterogeneous patient populations, and various causative microorganisms. The patient presented here was admitted to the emergency room because of nonspecific complaints, and her physical examination demonstrated no significant findings. Initial laboratory tests revealed mild hemolytic anemia and presence of schistocytes in peripheral blood smear. In the absence of fever, heart murmurs, or peripheral IE manifestations, the existence of new mechanical hemolysis in a patient with a biological prosthetic valve was the major clinical hint for IE and prompted the need to obtain blood cultures in the emergency room. This case demonstrates that IE should be suspected and ruled out in cases of new or worsening hemolysis in patients with intracardiac risk factors for IE. Based on this report and the reviewed literature, S. bovis should be considered as a rare but potential causative organism in cases of right-sided IE.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- IE:

-

Infective endocarditis

- IVDA:

-

Intravenous drug abuser

- S. aureus :

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- S. gallolyticus :

-

Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus

- S. bovis :

-

Streptococcus bovis

- LDH:

-

Lactate dehydrogenase

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- FDG PET-CT:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission tomography–computed tomography

References

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta J-P, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–128.

Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miró JM, Fowler VG, Bayer AS, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the international collaboration on endocarditis-prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):463–73.

Mylonakis E, Calderwood SB. Infective endocarditis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(18):1318–30.

Calderwood SB, Swinski LA, Waternaux CM, Karchmer AW, Buckley MJ. Risk factors for the development of prosthetic valve endocarditis. Circulation. 1985;72(1):31–7.

Incidence and risk factors of prosthetic valve endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1988;2(5):340–6.

Ivert TS, Dismukes WE, Cobbs CG, Blackstone EH, Kirklin JW, Bergdahl LA. Prosthetic valve endocarditis. Circulation. 1984;69(2):223–32.

Corredoira J, Alonso MP, Coira A, Casariego E, Arias C, Alonso D, et al. Characteristics of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its differences with Streptococcus viridans endocarditis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27(4):285–91.

Duval X, Papastamopoulos V, Longuet P, Benoit C, Perronne C, Leport C, et al. Definite Streptococcus bovis endocarditis: characteristics in 20 patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7(1):3–10.

Ballet M, Gevigney G, Garé JP, Delahaye F, Etienne J, Delahaye JP. Infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus bovis. A report of 53 cases. Eur Heart J. 1995;16(12):1975–80.

Carfagna P, Bianco G, Tarasi A, Tarasi D, Galiè M, Di Rosa R, et al. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis. Clinical and microbiological observations and review of the literature. Recent Prog Med. 1998;89(11):552–8.

Massaroni K, Francavilla R, De Rosa FG. Streptococcus bovis infectious endocarditis: clinical and epidemiological characteristics. Infez Med Riv Period Eziologia Epidemiol Diagn Clin E Ter Delle Patol Infett. 2003;11(4):189–95.

Pergola V, Di Salvo G, Habib G, Avierinos J-F, Philip E, Vailloud J-M, et al. Comparison of clinical and echocardiographic characteristics of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis with that caused by other pathogens. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88(8):871–5.

Herrero IA, Rouse MS, Piper KE, Alyaseen SA, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Reevaluation of Streptococcus bovis endocarditis cases from 1975 to 1985 by 16S ribosomal DNA sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40(10):3848–50.

Fitzmaurice GJ, McKenna AJ, Murphy J, McMullan R, O’Donnell ME. Streptococcus bovis bacteraemia: an evaluation of the long-term effect on cardiac outcomes. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;62(3):142–8.

Mello R, da Silva SM, Golebiosvki W, Weksler C, Lamas C. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis: analysis of cases between 2005 and 2014. Braz J Infect Dis. 2015;19(2):209–12.

Tripodi MF, Adinolfi LE, Ragone E, Mangoni ED, Fortunato R, Iarussi D, et al. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis and its association with chronic liver disease: an underestimated risk factor. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(10):1394–400.

González-Juanatey C, González-Gay MA, Llorca J, Testa A, Corredoira J, Vidán J, et al. Infective endocarditis due to Streptococcus bovis in a series of nonaddict patients: clinical and morphological characteristics of 20 cases and review of the literature. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19(10):1139–45.

Sidda A, Kallstrom G, Myers JP. Streptococcus bovis group bacteremia in the 21st century: review of 42 episodes over a 12-year period (2006–2017) at a large community teaching hospital. Infectious Disease in Clinical Practice [Internet]. 2018.

Mohee AR, West R, Baig W, Eardley I, Sandoe JAT. A case-control study: are urological procedures risk factors for the development of infective endocarditis? BJU Int. 2014;114(1):118–24.

Corredoira J, García-País MJ, Coira A, Rabuñal R, García-Garrote F, Pita J, et al. Differences between endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis and Enterococcus spp. and their association with colorectal cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2015;34(8):1657–65.

Beeching NJ, Christmas TI, Ellis-Pegler RB, Nicholson GI. Streptococcus bovis bacteraemia requires rigorous exclusion of colonic neoplasia and endocarditis. Q J Med. 1985;56(220):439–50.

García-País MJ, Rabuñal R, Alonso MP, Corredoira J. Prosthetic endocarditis caused by Streptococcus bovis group. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(7):1204–6.

Tripodi M-F, Fortunato R, Utili R, Triassi M, Zarrilli R. Molecular epidemiology of Streptococcus bovis causing endocarditis and bacteraemia in Italian patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2005;11(10):814–9.

Olmos C, Vilacosta I, Sarriá C, López J, Ferrera C, Sáez C, et al. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis: update from a multicenter registry. Am Heart J. 2016;171(1):7–13.

Boleij A, van Gelder MMHJ, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H. Clinical importance of Streptococcus gallolyticus infection among colorectal cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53(9):870–8.

Carrasco F, Anguita M, Ruiz M, Castillo JC, Delgado M, Mesa D, et al. Clinical features and changes in epidemiology of infective endocarditis on pacemaker devices over a 27-year period (1987–2013). EP Eur. 2016;18(6):836–41.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was not funded by any source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RS and TW collected and interpreted the patient’s clinical data, summarized the literature review, and wrote the manuscript. IK, EG, EC, IG, and RS were major contributors in writing the manuscript and defining the clinical conclusions. IG supervised the whole writing process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this is a case report, the Rabin Medical Center research ethics committee has confirmed that no ethical approval is required. This study does not include any identifying information of the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shapira, R., Weiss, T., Goldberg, E. et al. Streptococcus gallolyticus endocarditis on a prosthetic tricuspid valve: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports 15, 528 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03125-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-03125-5