Abstract

Background

Intrauterine midgut volvulus is a very rare, life-threatening condition, and prenatal diagnosis is difficult. In this article, we present a case of midgut volvulus followed by a pre-diagnosis of antenatal jejunal atresia.

Case presentation

A 1-day-old Turkish male baby, who was followed with a diagnosis of antenatal jejunal atresia, with a birth weight of 3600 g, delivered by cesarean section at 38 weeks of gestation from a 19-year-old mother in her fourth pregnancy, was taken to the newborn intensive care unit. The patient underwent surgery on the postnatal first day with a preliminary diagnosis of jejunal atresia. It was observed that the small intestine was rotated two full cycles from the mesenteric root. Bowel blood circulation was good. Volvulus was untwisted. There was malrotation. Ladd's procedure was performed. The baby was discharged on the seventh postoperative day with full oral feeding. The patient is still in the first postoperative year and follow-up has been uneventful.

Conclusion

Intrauterine midgut volvulus has been associated with high mortality in the literature. Differential diagnosis of midgut volvulus in patients with antenatal intestinal obstruction, close prenatal follow-up, appropriate delivery and timing of surgical intervention may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Small bowel volvulus occurs when bowel loops become twisted around the mesenteric artery or its branches. Midgut volvulus is common in infancy but is an extremely rare life-threatening condition during fetal development [1,2,3]. The twisting of the mesenteric artery leads to vascular congestion, impaired venous return and bowel necrosis [4]. It is a surgical emergency, and delay in diagnosis or treatment can increase fetal morbidity and mortality. Prenatal diagnosis of this type of malformation can be difficult in the absence of specific signs [5].

In this article, we present a case of midgut volvulus that was followed up with a pre-diagnosis of antenatal jejunal atresia starting from the antenatal period. This report is aimed at increasing awareness regarding patients with a diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation, because it is a very rare condition, and timely intervention could be life-saving.

Case presentation

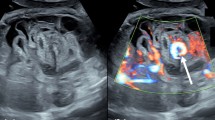

A 19-year-old Turkish mother in her fourth pregnancy was admitted to our institute with an ultrasound report suggestive of dilated small bowel loops at 24 weeks of gestation, which was followed up in the department of maternal fetal medicine with a pre-diagnosis of fetal bowel obstruction. The mother’ s previous obstetrical history was uneventful. There was no relationship between the parents. Repeat ultrasonography revealed a segmental distended bowel, with preserved motility and vascularization. There was no evidence of fetal anemia, and the amniotic fluid index was within the normal range. Jejunal atresia was considered as the first differential diagnosis in the fetus.

At 38 weeks of gestation, the mother underwent a planned cesarean section due to a history of previous cesarian section. A Turkish male child weighing 3600 g was delivered, with APGAR scores of 8 and 10 at 1 and 5 minutes, and pulse, blood pressure and temperature within normal ranges. The baby was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit under pediatric surgery. An infant feeding tube was secured in place. Bilious drainage from a nasogastric catheter was detected. On physical examination, the patient was alive and active. The abdomen was soft and had minimal distention. Neurological examination was normal. Septic findings were not observed in the patient. Laboratory values of the patient were within the normal range. An initial complete blood count revealed no anemia or leukocytosis, with hemoglobin of 15.2 g/dL, platelet clumping with a normal count (221,000/uL) and white blood count of 16,200/uL. There was no meconium output in the follow-up. In radiological evaluation, there was no distal gas passage on the abdominal X-ray, and air–fluid levels suggested proximal obstruction (Fig. 1).

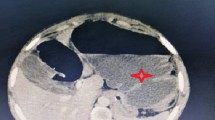

The patient underwent surgery on the first postnatal day. In laparotomy, it was observed that the small intestine was rotated two full cycles from the mesenteric root (Fig. 2). Bowel blood circulation was good. Volvulus was untwisted. There was a significant difference in diameter in the small bowel segment approximately 20 cm distal to Treitz. No atresia was detected. It was thought to be due to Ladd’s bands compression (Fig. 3). There was malrotation. A Ladd's procedure was performed. The patient was started on oral feeding on the first postoperative day. There was no problem in follow-up. He was discharged on the seventh postoperative day with full oral feeding. The patient is still in the first postoperative year, and the follow-up has been uneventful.

Discussion

The incidence of malrotation has been estimated at 1 in 6000 live births [6]. The most serious consequence of malrotation is volvulus [7]. Midgut volvulus is a rare condition. It occurs when a bowel loop twists around its mesenteric pedicle, thereby causing intermittent closed-loop bowel obstruction with or without bowel ischemia [7].

Prenatally diagnosed midgut volvulus remains a rare entity, seldom described in the literature [8] 9. Although volvulus with malrotation usually occurs in the late neonatal period, most cases of in utero volvulus occur without malrotation [8]. However, as in the case we presented, there may be cases of midgut volvulus accompanied by malrotation antenatally.

With early recognition and diagnosis of intestinal volvulus, a plan for neonatal surgery before fetal deterioration is extremely important, as there are reports in the literature of fetal demise in utero or postnatal death due to late intervention [4]. However, it is still challenging because of a lack of specific fetal symptoms or ultrasonographic signs.

There are various ultrasonographic signs of fetal intestinal volvulus, including dilated aperistaltic bowel loops, whirlpool sign or coffee bean sign [9]. Other indirect findings that may present in intestinal volvulus are ascites, discrete cystic or solid abdominal mass, peritoneal calcification, polyhydramnios, and particularly decreased fetal motion or abnormal fetal cardiotocography findings [4, 10].

Although the abovementioned ultrasonographic findings for volvulus have been described, most of the patients are followed up as a diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation without making a specific diagnosis. A retrospective study by Huang et al. described 68 cases with prenatal diagnosis of fetal bowel dilatation. They found that the congenital gastrointestinal tract anomalies included 24 cases (92.3%) of intestinal atresia, one case (3.85%) of small intestine volvulus and one case (3.85%) of malrotation [11]. In the case we presented, there was only fetal bowel dilatation. Bowel motility and vascularization were normal on Doppler studies. No signs of rotation were detected. Therefore, intestinal atresia was considered as a preliminary diagnosis.

It is extremely difficult to predict the time of volvulus and prognosis of the affected fetus owing to a wide range of presentation, from fetal demise to survivor with good outcome. Fortunately, although the case we presented healed with a good result, there are many cases in the literature of fetal demise due to intrauterine volvulus [12, 13]. Currently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American College of Radiology recommend routine sonograms in the first and/or second trimester, but state that no evidence exists to recommend routine sonograms in the third trimester [14]. Bawa and Kannan demonstrated different outcomes of fetal intestinal volvulus based on the performance of prenatal scanning, and suggested that a single third trimester scan for fetal anomalies may be an effective strategy to reduce perinatal mortality [15]. We believe that patients with fetal bowel dilatation should be closely followed in the third trimester.

Conclusion

Prenatal suspicion and/or diagnosis of intestinal volvulus is essential for newborn outcome, given the association with high mortality in the literature. Although the presented case had good results, differential diagnosis of midgut volvulus in patients with antenatal intestinal obstruction, close prenatal follow-up, and appropriate delivery and timing of surgical intervention may significantly reduce morbidity and mortality.

Availability of data and materials

All patient data are accessible from the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health system.

References

Gaikwad A, Ghongade D, Kittad P. Fatal midgut volvulus: a rare cause of gestational intestinal obstruction. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35(3):288–90.

Chung JH, Lim GY, We JS. Fetal primary small bowel volvulus in a child without intestinal malrotation. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:e15.

Sciarrone A, Teruzzi E, Pertusio A, et al. Fetal midgut volvulus: report of eight cases. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(8):1322–7.

Steffensen TS, Gilbert-Barness E, DeStefano KA, et al. Midgut volvulus causing fetal demise in utero. Fetal Pediatr Pathol. 2008;27(4–5):223–31.

Jequier S, Hanquinet S, Bugmann P, et al. Antenatal small-bowel volvulus without malrotation: ultrasound demonstration and discussion of pathogenesis. Pediatr Radiol. 2003;33:263–5.

M. Sidney Dassinger III. Malrotation. In Ashcraft's Pediatric Surgery, 6th ed. George W. Holcomb III, J.Patrick Murphy, Danial J. Ostlie, eds USA: Year Book 430,2014.

Chao HC, Kong MS, Chen J, et al. Sonographic features related to volvulus in neonatal intestinal malrotation. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:371–6.

Has R, Gunay S. “Whirlpool” sign in the prenatal diagnosis of intestinal volvulus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;20(3):307–8.

Yoo SJ, Park KW, Cho SY, et al. Definitive diagnosis of intestinal volvulus in utero. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1999;13(3):200–3.

Tava R, Yamakawa M, Harada S, et al. A case of massive meconium peritonitis in utero successfully managed by planned cardiopulmonary resuscitation of the newborn. Adv Neonatal Care. 2010;10(6):307–10.

Huang L, Huang D, Wang H, et al. Antenatal predictors of intestinal pathologies in fetal bowel dilatation. J Paediatr Child Helath. 2020;56(7):1097–100.

Allahdin S, Kay V. Ischaemic haemorrhagic necrosis of the intestine secondary to volvulus of the midgut: a silent cause of intrauterine death. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24(3):310.

Trachsel D, Heinimann K, Bosch N, et al. Cystic fibrosis and intrauterine death. J Perinatol. 2007;27:181–2.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 101: Ultrasonography in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2, Pt 1):451–61.

Bawa M, Kannan NL. Even a single third trimester antenatal fetal screening for congenital anomalies can be life saving. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77(1):103–4.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received no financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: GG, AİA. Data collection: GG. Analysis and interpretation of data: GG, AİA. Drafting of the manuscript: GG, AİA. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics committee approval was not obtained, as in Turkey there is no need for ethics approval for case studies. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s family.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s mother for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

No conflict of interest is declared by the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gerçel, G., Anadolulu, A.İ. Intrauterine midgut volvulus as a rare cause of intestinal obstruction: a case report. J Med Case Reports 15, 239 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02778-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02778-6