Abstract

Background

Childhood maltreatment (CM) is linked to long-term adverse health outcomes, including accelerated biological aging and cognitive decline. This study investigates the relationship between CM and various aging biomarkers: telomere length, facial aging, intrinsic epigenetic age acceleration (IEAA), GrimAge, HannumAge, PhenoAge, frailty index, and cognitive performance.

Methods

We conducted a Mendelian randomization (MR) study using published GWAS summary statistics. Aging biomarkers included telomere length (qPCR), facial aging (subjective evaluation), and epigenetic age markers (HannumAge, IEAA, GrimAge, PhenoAge). The frailty index was calculated from clinical assessments, and cognitive performance was evaluated with standardized tests. Analyses included Inverse-Variance Weighted (IVW), MR Egger, and Weighted Median (WM) methods, adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

CM was significantly associated with shorter telomere length (IVW: β = − 0.1, 95% CI − 0.18 to − 0.02, pFDR = 0.032) and increased HannumAge (IVW: β = 1.33, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.3, pFDR = 0.028), GrimAge (IVW: β = 1.19, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.2, pFDR = 0.040), and PhenoAge (IVW: β = 1.4, 95% CI 0.12 to 2.68, pFDR = 0.053). A significant association was also found with the frailty index (IVW: β = 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.49, pFDR = 0.006). No significant associations were found with facial aging, IEAA, or cognitive performance.

Conclusions

CM is linked to accelerated biological aging, shown by shorter telomere length and increased epigenetic aging markers. CM was also associated with increased frailty, highlighting the need for early interventions to mitigate long-term effects. Further research should explore mechanisms and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Child maltreatment (CM) refers to behaviors or neglect that harm children under 18, impacting their health, development, and dignity [1]. Forms of CM include physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, as well as neglect. This maltreatment distinctly influences social interaction patterns and long-term health outcomes. It is important to differentiate CM from Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE), which also include environmental factors and familial hardships not directly inflicted on the child, such as parental substance abuse or economic instability [2]. While many findings on ACE and CM overlap, and both can result in significant psychological and physiological consequences [3,4,5,6], not all individuals subjected to ACE suffer from CM [7]. Additionally, experiencing ACE or CM does not invariably result in trauma or stress due to the complexity of these processes and individual resilience [7]. Understanding the nuances between CM and ACE is crucial for developing comprehensive interventions and policies to support affected individuals effectively. Addressing CM remains critical due to inadequate global interventions [8]. Statistics indicate that 22.6% of adults report having experienced physical abuse, 36.3% emotional abuse, 26% sexual abuse, and 16.3% neglect during childhood [9]. About 20% of those maltreated in childhood do not recover [10]. Observational studies link CM to various adverse outcomes, including behavioral issues such as a decline in learning abilities [11], aggression [12], suicide [13], and increased likelihood of engaging in crime [14], cannabis or alcohol abuse [15, 16], or exhibiting sexually coercive behavior [17]. CM is also associated with several mental disorders, including depression [18], borderline personality disorder [19], post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety [20], conduct disorders [21], and eating disorders [22], along with physical consequences like chronic pain [23], inflammation [24], hormonal imbalances [25], sleep disturbances [26], and observable changes in functional MRI scans [27]. These conditions often correlate with poorer social outcomes in adulthood [28], and future research maybe continue to unveil further impacts. Continued exploration into CM is essential for developing a deeper understanding and more effective interventions.

Aging is a natural progression observed in organisms as they grow older. It is driven by cellular senescence, a phenomenon where cells irreversibly cease to divide, starting from the onset of life. This state significantly impairs every physiological function, heightening the risk of age-related diseases such as neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, cancers, and increases in mortality rates, ultimately reducing the duration of a healthy life [29, 30]. While age serves as a basic marker of aging, it does not capture the variability in aging processes among individuals or species [31]. This discrepancy highlights cases where young individuals may suffer from age-related conditions and premature aging, leading to early death. Consequently, there is an emerging focus on assessing both chronological and biological ages at the molecular level to more accurately gauge and predict aging [32, 33].

Researchers utilize the DNA methylation (DNAm) ratio at CpG dinucleotide sites to develop aging biomarkers based on the epigenetic clock [34], including HannumAge [35], intrinsic epigenetic age acceleration (IEAA) [36], GrimAge [37], and PhenoAge [38]. This innovative approach has enhanced our understanding and evaluation of aging processes. Telomeres, which are composed of repetitive nucleotide sequences that cap the ends of eukaryotic chromosomes, play a crucial role in cellular senescence due to their function in determining cell longevity [39]. As such, telomere length (TL) is a key indicator of aging. Facial aging involves analyzing aging through facial image features [40], while the Frailty index assesses frailty by collecting variables related to age-associated health deficits and assigning scores that reflect frailty levels [41]. Notably, the frailty index shows greater sensitivity to age variations compared to other frailty assessment tools [41]. Cognitive performance is often integrated with frailty assessments to provide a comprehensive measure of aging [42]. Current research supports that cellular senescence significantly influences these aging indices [43,44,45,46, 46,47,48].

Given the profound and lasting impacts of CM on health and development, there is a critical need to understand the underlying mechanisms linking early-life adversity to adverse health outcomes. Research highlights associations between CM and accelerated biological aging, such as shortened telomere length and altered epigenetic markers [43, 49]. However, causal relationships remain unclear due to potential confounding factors. To address these gaps, we designed this Mendelian randomization (MR) study to investigate the causal effects of CM on specific aging biomarkers: telomere length, facial aging, IEAA, GrimAge, HannumAge, PhenoAge, frailty index, and cognitive performance. Using genetic data from large-scale Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS), our study aims to provide robust evidence on how CM influences biological aging processes, ultimately informing prevention and intervention strategies to mitigate the long-term health consequences of early-life stress.

Methods

Study design

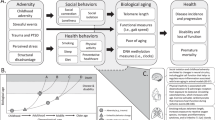

Our research synthesizes a variety of data sources, including meta-analytical results from published GWAS and datasets obtained from the UK Biobank (UKB). Within the framework of MR study, we employ Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) as proxies for both phenotypic and genetic Instrumental Variables (IVs). For inclusion, SNPs must meet three essential MR criteria: first, a strong association with CM (Assumption 1); second, independence from potential confounders that could affect the study outcomes (Assumption 2); and third, the absence of a direct causal link between the IVs and the outcomes (Assumption 3) [50]. Figure 1 illustrates this specific process.

Schematic representation of the three hypotheses of the MR study. Solid arrow lines indicate MR analysis processes and can only influence the outcome by exposure. Dashed arrows indicate instrumental variables independent of any confounding variables. IVW, inverse-variance weighted; LD, linkage disequilibrium; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism

Genetic instrument selection

In our MR study, CM was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Screener from the UKB, as detailed by Warrier et al. [51] in The Lancet Psychiatry. This meta-analysis incorporated data from five cohorts: the UKB (n = 143,473), the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (n = 26,290), the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (n = 8346), the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study (n = 5400), and the Generation R Study (n = 1905), totaling 185,414 individuals of primarily European ancestry. The genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified 14 independent loci associated with CM, revealing significant genetic correlations among different subtypes and reporting methods. Detailed information on the data sources, including sample size, age range, demographics, and measures of CM, is provided in Table 1. This comprehensive dataset provided a robust foundation for our MR analysis, enabling us to investigate the potential causal effects of CM on Aging.

The Childhood Trauma Screener evaluates five subtypes of maltreatment—emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect—using five items, each rated on a scale from 0 (never true) to 4 (very often true). Participants were classified as having experienced abuse or neglect if they reported a score greater than 0 on the respective items. Combined CM was identified when both abuse and neglect were reported [51]. The screener has been validated in several studies, demonstrating good reliability and validity. Its validity has been confirmed through comparisons with clinical interview data, showing strong correlations, which support its use as a reliable measure of CM [52, 53]. The Childhood Trauma Screener is widely used in large-scale studies, including the UKB and the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, due to its simplicity and effectiveness in capturing various forms of childhood trauma [51, 54].

For the genetic component of our study, instrumental variables were defined using SNPs that reached genome-wide significance (P < 5 × 10−8) in GWAS of CM, also based on UKB data. To mitigate confounding from linkage disequilibrium, we applied pruning with thresholds set at LD r2 < 0.001 and a physical distance exceeding 10,000 kilobases [55].

The validity of SNPs as instrumental variables was further assessed by computing the F-statistic for each SNP. The calculation used the formula: F = [(N − k − 1)/k] × [R2/(1 − R2)] [56], where R2 = 2 × (1 − MAF) × MAF × (β/SD)2 [57, 58]. The variables in this formula are defined as follows: N is the total sample size, k is the number of selected SNPs, β represents the estimated effect of each SNP on CM, SD is the standard deviation of β, and MAF denotes the minor allele frequency. SNPs with an F-statistic below 10 were excluded to ensure the strength and reliability of the instrumental variables.

By employing these stringent criteria for SNP selection and validation, we aimed to control for genetic factors that could contribute to the development or risk of telomere length, facial aging, IEAA, GrimAge, HannumAge, PhenoAge, frailty index, and cognitive performance. This ensures that the observed relationships between CM and these outcomes are not confounded by shared genetic tendencies. The assessment accounted for the influence of specific genetic variants on the likelihood of experiencing CM, allowing us to accurately evaluate the direct effect of CM on these aging-related biomarkers. This approach strengthens the robustness of our findings, ensuring that the relationships between CM and the various aging-related outcomes are independent of underlying genetic predispositions.

Data source for various aging-related biomarkers

The data for telomere length were obtained from a large-scale GWAS involving 472,174 well-characterized participants from the UK Biobank. This study measured leukocyte telomere length using an established quantitative PCR assay [59].

Facial aging data were sourced from the UK Biobank, utilizing a comprehensive GWAS pipeline developed by the MRC-IEU for the full UK Biobank genetic data (version 3, March 2018) [60]. The methodology for assessing perceived age has been detailed in previous studies [61, 62]. Subjective evaluations of facial aging were obtained through the questionnaire item: “Do people say that you look younger than you are, older than you are, about your age, do not know, and prefer not to answer?”.

The data for PhenoAge, GrimAge, HannumAge, and IEAA were derived from a comprehensive GWAS involving 34,710 individuals of European ancestry and 6195 individuals of African American ancestry. PhenoAge is a second-generation epigenetic clock that incorporates a measure trained on mortality, using 42 clinical measures and age as input features. GrimAge, also a second-generation clock, includes DNA methylation-based measures of smoking, plasma protein levels, and other factors to predict mortality risk more accurately. HannumAge, a first-generation epigenetic clock, uses penalized regression models on DNA methylation data to predict chronological age, and IEAA is a derivative of the Horvath clock that provides an intrinsic measure of biological aging independent of blood cell type proportions. These clocks, developed and validated in a large-scale GWAS, serve as robust biomarkers of biological aging, linked to morbidity and mortality risks [63].

Frailty-related SNPs were derived from an extensive GWAS meta-analysis involving European participants from the UK Biobank (n = 164,610, aged 60–70 years old, 51.3% females) and TwinGene (n = 10,616, aged 41–87 years old, 52.5% females) [64]. Frailty was evaluated using the frailty index, which is based on the accumulation of 49 health deficits throughout the life course. This well-validated measure is widely employed in clinical practice [65]

SNPs related to cognitive performance were compiled from the UK Biobank and Cognitive Genomics Consortium datasets [66], covering approximately 10 million genetic variations in 257,841 individuals of predominantly European ancestry. The GWAS focused on the General Cognitive Factor, using educational achievement and various cognitive assessments such as digital symbol coding, digit span, word reading, semantic fluency, visual memory, vocabulary, speech memory, phoneme fluency, and footprint testing. This diverse set of measures allowed for a comprehensive analysis of cognitive abilities, including memory, language, and processing speed.

The demographic characteristics of the cohorts utilized in our GWAS for various phenotypes—including telomere length, facial aging, epigenetic age markers, frailty index, and cognitive performance—are summarized in Table 2. This table provides detailed information on sample size, gender distribution, population ancestry, mean age, age range, and relevant PMID/GWAS ID for each phenotype. This comprehensive overview ensures clarity and consistency in presenting the demographic context of our study populations. Notably, all datasets used in this study were of European or primarily European origin, with no overlap between exposures and outcomes. Ethical approval was not required for this study, as it employed publicly available summary-level statistics from previous GWAS research, which had already received ethical approval from their respective institutional review boards. The use of de-identified, summary-level data ensured the protection of individual privacy and confidentiality.

Exclusion of confounding and palindromic SNPs

To adhere to the second assumption of MR, each SNP and its associated phenotypes were assessed using the Phenoscanner V2 database (http://www.phenoscanner.medschl.cam.ac.uk/, accessed on 31 Dec 2023), and SNPs associated with traits related to aging were excluded at an r2 threshold greater than 0.80. To harmonize the data for exposure and outcome, all palindromic SNPs with intermediate allele frequencies were removed from the selected SNPs [67], Palindromic SNPs are those with A/T or G/C alleles, and intermediate allele frequencies range between 0.01 and 0.30 [68].

Statistical analysis

In this study, we employed the Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW) method as the primary analytical approach, utilizing a random effects model to estimate associations for genetically predicted aging. Causal estimates were derived by meta-analyzing SNP-specific Wald ratio estimates, calculated as the ratio of the beta coefficient of the SNP's effect on the outcome to its effect on the exposure [68]. These estimates were weighted by their standard errors, applying either fixed- or random-effects models depending on the observed heterogeneity. Standard errors for each Wald ratio were computed using the delta method. Results are presented as beta coefficients (β) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). A β below 0 suggests the exposure may be protective, while a β above 0 indicates it may be a risk factor.

To validate our findings, we conducted three sensitivity analyses: the Weighted Median method, MR-Egger regression, and the MR-PRESSO test. Specifically, the Weighted Median method assumes at least 50% of the SNPs are valid instruments and provides robust causal estimates [69]. Additionally, MR-Egger regression, which detects and adjusts for pleiotropic effects, indicated no significant horizontal pleiotropy with an intercept P value greater than 0.05 [70]. Furthermore, the MR-PRESSO test identifies and excludes outliers, refining causal estimates after their removal [71].

Further, we also evaluated the strength of the genetic instruments using the F statistic, which is crucial given the significant sample overlap between exposure and outcome data in the UK Biobank study. To assess heterogeneity among SNP estimates, we used the Cochrane Q test [72]. Additionally, we applied the False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction to the P values obtained from the IVW results to control for the potential increase in Type I errors due to multiple comparisons. This correction ensures that the proportion of false positives among the declared significant results is limited. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (version 4.1.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), employing relevant packages such as ‘devtools’, ‘TwoSampleMR’, ‘LDlinkR’, and ‘MR-PRESSO [71]. All tests were two-sided, and findings from MR analyses and sensitivity tests were considered statistically significant at a P value less than 0.05.

Results

Telomere length

Our analysis revealed a significant negative association between CM and telomere length. Using the IVW method, we found that CM was significantly associated with shorter telomere length (β = − 0.1, 95% CI − 0.18 to − 0.02, pFDR = 0.032). Neither MR-Egger regression (β = − 0.14, 95% CI − 0.52 to 0.24, pFDR = 0.491) nor Weighted Median (WM) (β = − 0.08, 95% CI − 0.17 to 0.01, pFDR = 0.094) showed significant associations.

Facial aging

The association between CM and facial aging was not statistically significant. IVW analysis yielded a β of − 0.03 (95% CI − 0.07 to 0.01, pFDR = 0.192), while MR-Egger regression (β = − 0.06, 95% CI − 0.22 to 0.11, pFDR = 0.507) and WM (β = − 0.01, 95% CI − 0.05 to 0.05, pFDR = 0.965) also did not demonstrate significant associations.

IEAA

For IEAA, the associations with CM were non-significant across all methods. IVW indicated a β of − 0.14 (95% CI − 1.26 to 0.97, pFDR = 0.799), MR-Egger showed β = − 2.13 (95% CI − 3.29 to 0.3, pFDR = 0.442), and WM presented β = 0.26 (95% CI − 1.1 to 1.62, pFDR = 0.706).

GrimAge

CM was positively associated with GrimAge using IVW (β = 1.19, 95% CI 0.19 to 2.2, pFDR = 0.040). However, MR-Egger (β = − 0.72, 95% CI − 2.38 to 3.93, pFDR = 0.768) and WM (β = 1.03, 95% CI − 0.22 to 2.29, pFDR = 0.107) did not show significant results.

HannumAge

A significant positive association was observed between CM and HannumAge via IVW (β = 1.33, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.3, pFDR = 0.028). MR-Egger regression (β = − 0.24, 95% CI − 2.6 to 2.11, pFDR = 0.915) and WM (β = 1.03, 95% CI − 0.28 to 2.33, pFDR = 0.124) did not indicate significant associations.

PhenoAge

The association between CM and PhenoAge was significant when using IVW (β = 1.4, 95% CI 0.12 to 2.68, pFDR = 0.053). Neither MR-Egger (β = − 2.69, 95% CI − 4.56 to − 2.18, pFDR = 0.399) nor WM (β = 0.67, 95% CI − 0.98 to 2.31, pFDR = 0.426) showed significant associations.

Frailty index

CM was significantly associated with an increased frailty index using IVW (β = 0.31, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.49, pFDR = 0.006). MR-Egger regression (β = − 0.36, 95% CI − 0.98 to 0.28, pFDR = 0.291) and WM (β = 0.19, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.37, pFDR = 0.03) did not yield significant associations.

Cognitive performance

There were no significant associations found between CM and cognitive performance across all methods. IVW analysis showed a β of − 0.08 (95% CI − 0.2 to 0.03, pFDR = 0.192), MR-Egger regression indicated β = − 0.28 (95% CI − 0.75 to 0.19, pFDR = 0.287), and WM presented β = − 0.11 (95% CI − 0.24 to 0.03, pFDR = 0.123).

In summary, our results indicate that CM is significantly associated with shorter telomere length, increased GrimAge, HannumAge, PhenoAge, and higher frailty index. These findings highlight the long-term biological impacts of early-life stress. No significant associations were observed between CM and facial aging, IEAA, or cognitive performance, suggesting that the effects of CM may be specific to certain aging biomarkers. As illustrated in Fig. 2’s forest plot and supported by the scatter plots in Fig. 3, these results underscore the specific pathways through which early-life stress can influence biological aging.

Scatter plots of the causal relationships between CM and various aging-related biomarkers. Scatter plots illustrating the causal relationships between CM and various aging-related biomarkers, including telomere length, facial aging, GrimAge, HannumAge, PhenoAge, IEAA, frailty index, and cognitive performance. Each plot shows the SNP effect on CM (x-axis) versus the SNP effect on the respective biomarker (y-axis). The lines represent different MR methods: Inverse Variance Weighted (IVW), MR-Egger regression, Weighted Median, Simple Mode, and Weighted Mode

Heterogeneity and pleiotropy

Table 3 presents the results of the sensitivity analyses conducted to ensure the robustness of our MR findings. The MR-Egger regression intercepts for all outcomes were close to zero, with P values above 0.05, indicating no evidence of substantial directional pleiotropy. Cochran’s Q test revealed significant heterogeneity for telomere length (Q value = 20.72, P = 0.036) and frailty index (Q value = 21.33, P = 0.006), suggesting variability in the SNP effects across these outcomes. Despite the observed heterogeneity, the IVW results remain reliable. The MR-PRESSO global test showed no significant evidence of distortion due to pleiotropy for most outcomes, although telomere length approached significance (P = 0.051). The F statistics for the genetic instruments were all above the conventional threshold of 10, indicating strong instrument strength and suggesting that weak instrument bias is unlikely. These findings, along with the lack of significant pleiotropy indicated by the MR-Egger intercepts and MR-PRESSO global tests, support the robustness of our causal estimates and suggest they are reliable and not substantially influenced by pleiotropy or weak instruments.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to establish a connection between CM and aging using the MR approach in GWAS. Our findings indicate that CM is negatively correlated with TL and positively correlated with HannumAge, GrimAge, PhenoAge, and the Frailty index. These correlations suggest that CM may accelerate epigenetic and biomolecular aging.

Our MR study indicates that increased exposure to CM correlates with shorter TL. Shortened telomeres compromise chromosome protection, potentially hastening biological aging [39]—a conclusion supported by our findings. A previous study of 31 adults used quantitative polymerase chain reaction to measure telomeres, demonstrating that CM contributes to shortened telomeres in leukocytes [73]. However, a subsequent larger study, involving 123 cases and 1751 control subjects, employing the Southern blot method alongside rigorous statistical approaches, did not observe an impact of CM on TL [74]. Nevertheless, recent research increasingly supports the link between CM and telomere shortening [43, 49, 75, 76]. The exact mechanisms by which CM influences TL remain elusive. One prevailing theory suggests that adverse childhood experiences, such as maltreatment, may elevate oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, resulting in DNA damage and thus, telomere shortening. Furthermore, chronic stress could diminish telomerase activity—primarily the functions of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and telomerase RNA component (TERC)—impairing telomere maintenance and accelerating the aging process [39, 77].

In our study, we observed that CM is positively correlated with three epigenetic age markers: HannumAge, GrimAge, and PhenoAge. These epigenetic clocks, which include HannumAge, IEAA, GrimAge, and PhenoAge, are designed to measure both chronological and biological ages based on DNAm levels. Understanding these clocks is crucial for interpreting our findings. Originally, it was challenging to quantify age and aging using DNAm. However, advancements in genomic DNA sequencing technology and microarray hybridization have greatly improved the accuracy of DNAm measurements [63]. By combining diverse biological tissue samples with specialized algorithms, researchers developed epigenetic clocks with varying strengths and limitations. HannumAge, a first-generation clock, is geared toward predicting chronological age using DNAm from leukocytes in saliva samples [35]. It is less effective at predicting physiological conditions and lifespan compared to newer models [35]. The second-generation clocks, GrimAge and PhenoAge, offer more comprehensive assessments. GrimAge integrates DNAm data with mortality-related indicators such as smoking and plasma protein levels, enhancing predictions of health outcomes like mortality and cancer [78]. PhenoAge, utilizing data from whole blood cells, excels in predicting a range of outcomes, including death, cancer, healthy lifespan, physical function, and Alzheimer's disease [38]. Linking these insights to our MR findings, we conclude that CM not only accelerates aging but also increases the likelihood of mortality and adverse health conditions. This pattern aligns with previous research, including studies in bipolar disorder patients, showing that CM elevates GrimAge [79], and supports evidence that CM increases PhenoAge [47, 80].

Our MR study analysis indicates a positive correlation between CM and the frailty. To date, no direct studies link CM with frailty, making our findings particularly significant. A comprehensive cross-sectional study in the UK has shown that adults with greater exposure to CM are more likely to exhibit increased frailty [81]. Even though this analysis used the frailty phenotype model specific to the UK Biobank, this supports a consistent relationship in terms of frailty attributes. Additionally, a large study in Canada found a positive dose–response relationship between the frailty and ACE [46]. This study employed a broader definition of ACE compared to CM, indicating some alignment but also notable differences between our findings and existing research.

The biological mechanisms underlying changes in aging biomarkers due to CM may involve the activation of the stress system and subsequent release of neuroendocrine hormones [82]. This exposure to stress biologically embeds itself in the body, destabilizing the physiological system and activating the stress response, which significantly impacts the regulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis [83]. For instance, in response to stress, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and arginine vasopressin are released from the hypothalamus, triggering the anterior pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This hormone then stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce glucocorticoids like cortisol. Cortisol plays a critical role in regulating the HPA axis through a negative feedback loop and influences both peripheral and central system functions. Additionally, stress induces the adrenal medulla to secrete catecholamines (norepinephrine and epinephrine), which affect the peripheral system. The modifications in the HPA axis and related hormonal responses are intricately linked to cognitive behavior changes and health outcomes, involving complex interactions across various physiological and psychological regulatory levels [84,85,86,87].

Additionally, stress can also cause changes in mitochondrial structure and function through mechanisms such as increased oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA damage, which may occur prior to neuroendocrine changes, making it one of the micro-mechanisms by which CM accelerates aging [88]. However, these results are mainly based on animal experiments, which have limitations regarding sample size, gender, sample selection, and measurement methods. A recent study involving 754 human samples of all genders used multi-model linear regression analysis to find significant effects of CM on mitochondrial function [89]. The study measured two skeletal muscle mitochondrial function indicators in peripheral blood—Maximal Oxidative Phosphorylation (Max OXPHOS) and Maximal ATP Production (ATPmax)—which are considered important standards in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Although this provides new evidence for the mitochondrial mechanisms by which CM leads to aging, further large-scale studies are needed to verify and expand these findings.

Conclusion

Our MR study underscores the significant effects of CM on telomere length, HannumAge, GrimAge, PhenoAge, and frailty index. However, associations with facial aging, IEAA, and cognitive performance were not statistically significant. These findings may be influenced by various factors, including lifestyle, environmental exposures, and genetic variations. The complexity of measuring cognitive performance could also obscure a direct link with CM. Although CM is not an exclusive determinant of all health outcomes, it plays a crucial role. This underscores the importance of considering multiple factors when assessing the long-term effects of CM, which is essential for developing effective intervention strategies and public health policies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths, including the use of robust analytical methods (IVW, Weighted Median, MR-Egger, and MR-PRESSO), comprehensive data from large-scale GWAS like the UK Biobank, and thorough sensitivity analyses indicating reliable causal estimates with high F statistics.

However, the study has limitations: it included primarily European ancestry individuals, limiting generalizability. Despite efforts to exclude confounders, residual confounding is possible. The GWAS for CM lacked subgroup analyses, and no GWAS for Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) was available, preventing stratified analyses. Some outcomes, like facial aging and cognitive performance, relied on self-reported or proxy measures, potentially introducing measurement error. Finally, our study did not cover all aging biomarkers. Future research should include diverse populations, additional biomarkers, and investigate stratified effects of CM and ACEs for a comprehensive understanding of early-life stress impacts on aging.

Availability of data and materials

The data used for analysis were obtained from published studies and public databases. Specifically, the data were sourced from the IEU Open GWAS Project (https://gwas.mrcieu.ac.uk/datasets) and the GWAS data for the epigenetic clocks used in this MR study were obtained from the University of Edinburgh's DataShare repository (https://datashare.ed.ac.uk/handle/10283/3645). All data generated during this study are included in this article. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Child maltreatment [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 28]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/child-maltreatment.

Guinn AS, Ottley PG, Anderson KN, Oginga ML, Gervin DW, Holmes GM. Leveraging surveillance and evidence: preventing adverse childhood experiences through data to action. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62:S24-30.

Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:389–96.

Petruccelli K, Davis J, Berman T. Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2019;97: 104127.

Bussières A, Hancock MJ, Elklit A, Ferreira ML, Ferreira PH, Stone LS, et al. Adverse childhood experience is associated with an increased risk of reporting chronic pain in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14:2284025.

Lin L, Wang HH, Lu C, Chen W, Guo VY. Adverse childhood experiences and subsequent chronic diseases among middle-aged or older adults in China and associations with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2130143.

The Lancet Psychiatry null. Responding to childhood trauma. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:759.

van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Coughlan B, Reijman S. Annual Research Review: Umbrella synthesis of meta-analyses on child maltreatment antecedents and interventions: differential susceptibility perspective on risk and resilience. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:272–90.

Kelly C, Street C, Building MES. Child Maltreatment 2019.

Walsh WA, Dawson J, Mattingly MJ. How are we measuring resilience following childhood maltreatment? Is the research adequate and consistent? What is the impact on research, practice, and policy? Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11:27–41.

Fisher JH, Widom CS. Child maltreatment and cognitive and academic functioning in two generations. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;115: 105011.

Li W, Yang J, Gao L, Wang X. Childhood maltreatment and adolescents’ aggression: a moderated mediation model of callous-unemotional traits and friendship quality. Child Maltreat. 2022;27:683–92.

Zelazny J, Melhem N, Porta G, Biernesser C, Keilp JG, Mann JJ, et al. Childhood maltreatment, neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:1085–93.

Baidawi S, Papalia N, Featherston R. Gender differences in the maltreatment-youth offending relationship: a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24:1140–56.

Abajobir AA, Najman JM, Williams G, Strathearn L, Clavarino A, Kisely S. Substantiated childhood maltreatment and young adulthood cannabis use disorders: a pre-birth cohort study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;256:21–31.

Bull C, Trott M, Najman JM, Arnautovska U, Siskind D, Warren N, et al. Associations between child maltreatment and hospital admissions for alcohol and other substance use-related disorders up to 40 years of age: results from the childhood adversity and lifetime morbidity study. Addiction. 2024;119:1253–63.

Forsman M, Johansson A, Santtila P, Sandnabba K, Långström N. Sexually coercive behavior following childhood maltreatment. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44:149–56.

Nelson J, Klumparendt A, Doebler P, Ehring T. Childhood maltreatment and characteristics of adult depression: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:96–104.

Monteleone AM, Cascino G, Marciello F, D’Agostino G, Caivano V, Monteleone P, et al. Clinical and neuroendocrine correlates of childhood maltreatment history in adults with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2020;22:749–56.

Leenarts LEW, Diehle J, Doreleijers TAH, Jansma EP, Lindauer RJL. Evidence-based treatments for children with trauma-related psychopathology as a result of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;22:269–83.

De Sanctis VA, Nomura Y, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Childhood maltreatment and conduct disorder: independent predictors of criminal outcomes in ADHD youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36:782–9.

Talmon A, Widom CS. Childhood maltreatment and eating disorders: a prospective investigation. Child Maltreat. 2022;27:88–99.

Cay M, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Teicher MH, van der Heijden H, Ongur D, Shinn AK, et al. Childhood maltreatment and its role in the development of pain and psychopathology. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:195–206.

Orellana SC, Bethlehem RAI, Simpson-Kent IL, van Harmelen A-L, Vértes PE, Bullmore ET. Childhood maltreatment influences adult brain structure through its effects on immune, metabolic, and psychosocial factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2024;121: e2304704121.

White LO, Ising M, von Klitzing K, Sierau S, Michel A, Klein AM, et al. Reduced hair cortisol after maltreatment mediates externalizing symptoms in middle childhood and adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58:998–1007.

Fitzgerald M. Serial indirect effects from childhood maltreatment to adult chronic health conditions through contemporary family relationships and mental health problems: inquiry into sleep disturbances and stress. Psychol Trauma. 2023;16:S215.

Lim L, Howells H, Radua J, Rubia K. Aberrant structural connectivity in childhood maltreatment: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;116:406–14.

Jaffee SR, Ambler A, Merrick M, Goldman-Mellor S, Odgers CL, Fisher HL, et al. Childhood maltreatment predicts poor economic and educational outcomes in the transition to adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:1142–7.

Borghesan M, Hoogaars WMH, Varela-Eirin M, Talma N, Demaria M. A senescence-centric view of aging: implications for longevity and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30:777–91.

Wang K, Liu H, Hu Q, Wang L, Liu J, Zheng Z, et al. Epigenetic regulation of aging: implications for interventions of aging and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:374.

Levine ME. Modeling the rate of senescence: Can estimated biological age predict mortality more accurately than chronological age? J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:667–74.

Hayflick L. Biological aging is no longer an unsolved problem. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:1–13.

Li A, Koch Z, Ideker T. Epigenetic aging: biological age prediction and informing a mechanistic theory of aging. J Intern Med. 2022;292:733–44.

Noroozi R, Ghafouri-Fard S, Pisarek A, Rudnicka J, Spólnicka M, Branicki W, et al. DNA methylation-based age clocks: from age prediction to age reversion. Ageing Res Rev. 2021;68: 101314.

Bocklandt S, Lin W, Sehl ME, Sánchez FJ, Sinsheimer JS, Horvath S, et al. Epigenetic predictor of age. PLoS ONE. 2011;6: e14821.

Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19:371–84.

Lu AT, Quach A, Wilson JG, Reiner AP, Aviv A, Raj K, et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:303–27.

Levine ME, Lu AT, Quach A, Chen BH, Assimes TL, Bandinelli S, et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging (Albany NY). 2018;10:573–91.

Chakravarti D, LaBella KA, DePinho RA. Telomeres: history, health, and hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2021;184:306–22.

Chen W, Qian W, Wu G, Chen W, Xian B, Chen X, et al. Three-dimensional human facial morphologies as robust aging markers. Cell Res. 2015;25:574–87.

Theou O, Haviva C, Wallace L, Searle SD, Rockwood K. How to construct a frailty index from an existing dataset in 10 steps. Age Ageing. 2023;52:afad221.

Shaaban CE, Rosano C, Zhu X, Rutherford BR, Witonsky KR, Rosso AL, et al. Discordant biological and chronological age: implications for cognitive decline and frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2023;78:2152–61.

Connor A, Starnino L, Busque L, Tardif J-C, Bourgoin V, Dubé M-P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and leukocyte telomere length in men and women with chronic illness: an evaluation of moderating and mediating influences. Psychol Med. 2023;53:6242–52.

Dammering F, Martins J, Dittrich K, Czamara D, Rex-Haffner M, Overfeld J, et al. The pediatric buccal epigenetic clock identifies significant ageing acceleration in children with internalizing disorder and maltreatment exposure. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;15: 100394.

Lin L, Cao B, Chen W, Li J, Zhang Y, Guo VY. Association of adverse childhood experiences and social isolation with later-life cognitive function among adults in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e2241714.

Mian O, Anderson LN, Belsky DW, Gonzalez A, Ma J, Sloboda DM, et al. Associations of adverse childhood experiences with frailty in older adults: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging. Gerontology. 2022;68:1091–100.

Rampersaud R, Protsenko E, Yang R, Reus V, Hammamieh R, Wu GWY, et al. Dimensions of childhood adversity differentially affect biological aging in major depression. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:431.

Wertz J, Caspi A, Ambler A, Broadbent J, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, et al. Association of history of psychopathology with accelerated aging at midlife. JAMA Psychiat. 2021;78:530–9.

Ridout KK, Levandowski M, Ridout SJ, Gantz L, Goonan K, Palermo D, et al. Early life adversity and telomere length: a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:858–71.

Davies NM, Holmes MV, Davey SG. Reading Mendelian randomisation studies: a guide, glossary, and checklist for clinicians. BMJ. 2018;362: k601.

Warrier V, Kwong ASF, Luo M, Dalvie S, Croft J, Sallis HM, et al. Gene–environment correlations and causal effects of childhood maltreatment on physical and mental health: a genetically informed approach. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:373–86.

Brown RC, Berenz EC, Aggen SH, Gardner CO, Knudsen GP, Reichborn-Kjennerud T, et al. Trauma exposure and axis I psychopathology: a co-twin control analysis in Norwegian Young Adults. Psychol Trauma. 2014;6:652–60.

Schaefer JD, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Danese A, Fisher HL, Houts R, et al. Adolescent victimization and early-adult psychopathology: approaching causal inference using a longitudinal twin study to rule out noncausal explanations. Clin Psychol Sci. 2018;6:352–71.

Dalvie S, Maihofer AX, Coleman JRI, Bradley B, Breen G, Brick LA, et al. Genomic influences on self-reported childhood maltreatment. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:38.

Shen J, Zhou H, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhou T, Yang Y, et al. A modifiable risk factors atlas of lung cancer: a Mendelian randomization study. Cancer Med. 2021;10:4587–603.

Burgess S, Thompson SG, CRP CHD Genetics Collaboration. Avoiding bias from weak instruments in Mendelian randomization studies. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:755–64.

Yuan S, Xiong Y, Larsson SC. An atlas on risk factors for multiple sclerosis: a Mendelian randomization study. J Neurol. 2021;268:114–24.

Wu P-F, Zhang W, Zhang X, Zhang R. Application and interpretation of Mendelian randomization approaches in exploring the causality between folate and coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:1299–300.

Codd V, Wang Q, Allara E, Musicha C, Kaptoge S, Stoma S, et al. Polygenic basis and biomedical consequences of telomere length variation. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1425–33.

Ruth Mitchell E. MRC IEU UK Biobank GWAS pipeline version 2 [Internet]. data.bris. 2019 [cited 2024 Jun 6]. https://data.bris.ac.uk/data/dataset/pnoat8cxo0u52p6ynfaekeigi.

Zhan Y, Hägg S. Association between genetically predicted telomere length and facial skin aging in the UK Biobank: a Mendelian randomization study. GeroScience. 2020;43:1519–25.

Jiang L, Zheng Z, Fang H, Yang J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1616–21.

McCartney DL, Min JL, Richmond RC, Lu AT, Sobczyk MK, Davies G, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify 137 genetic loci for DNA methylation biomarkers of aging. Genome Biol. 2021;22:194.

Atkins JL, Jylhävä J, Pedersen NL, Magnusson PK, Lu Y, Wang Y, et al. A genome-wide association study of the frailty index highlights brain pathways in ageing. Aging Cell. 2021;20: e13459.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394:1365–75.

Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, et al. Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1112–21.

Lukkunaprasit T, Rattanasiri S, Ongphiphadhanakul B, McKay GJ, Attia J, Thakkinstian A. Causal associations of urate with cardiovascular risk factors: two-sample Mendelian randomization. Front Genet. 2021;12: 687279.

Cui Z, Hou G, Meng X, Feng H, He B, Tian Y. Bidirectional causal associations between inflammatory bowel disease and ankylosing spondylitis: a two-sample Mendelian randomization analysis. Front Genet. 2020;11: 587876.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Haycock PC, Burgess S. Consistent estimation in Mendelian randomization with some invalid instruments using a weighted median estimator. Genet Epidemiol. 2016;40:304–14.

Bowden J, Davey Smith G, Burgess S. Mendelian randomization with invalid instruments: effect estimation and bias detection through Egger regression. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:512–25.

Verbanck M, Chen C-Y, Neale B, Do R. Publisher Correction: Detection of widespread horizontal pleiotropy in causal relationships inferred from Mendelian randomization between complex traits and diseases. Nat Genet. 2018;50:1196.

Greco MFD, Minelli C, Sheehan NA, Thompson JR. Detecting pleiotropy in Mendelian randomisation studies with summary data and a continuous outcome. Stat Med. 2015;34:2926–40.

Tyrka AR, Price LH, Kao H-T, Porton B, Marsella SA, Carpenter LL. Childhood maltreatment and telomere shortening: preliminary support for an effect of early stress on cellular aging. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:531–4.

Glass D, Parts L, Knowles D, Aviv A, Spector TD. No correlation between childhood maltreatment and telomere length. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:e21–2 (Author reply e23–24).

Connor A, Deschamps A, Busque L, Tardif J-C, Bourgoin V, Dubé M-P, et al. Childhood maltreatment and leukocyte telomere length: cardiac vagal activity influences the relation in older adults. Psychosom Med. 2024;86:146–56.

Vincent J, Hovatta I, Frissa S, Goodwin L, Hotopf M, Hatch SL, et al. Assessing the contributions of childhood maltreatment subtypes and depression case-control status on telomere length reveals a specific role of physical neglect. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:16–22.

Lu AT, Xue L, Salfati EL, Chen BH, Ferrucci L, Levy D, et al. GWAS of epigenetic aging rates in blood reveals a critical role for TERT. Nat Commun. 2018;9:387.

Levine ME, Hosgood HD, Chen B, Absher D, Assimes T, Horvath S. DNA methylation age of blood predicts future onset of lung cancer in the women’s health initiative. Aging (Albany NY). 2015;7:690–700.

Bourdon C, Etain B, Spano L, Belzeaux R, Leboyer M, Delahaye-Duriez A, et al. Accelerated aging in bipolar disorders: an exploratory study of six epigenetic clocks. Psychiatry Res. 2023;327: 115373.

Herrero-Roldán S, Rodrigo MJ, Hernández-Cabrera JA, Mitchell C, López M, Alcoba-Florez J, et al. Reduction in epigenetic age acceleration is related to empathy in mothers with neglectful caregiving. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1376.

Hanlon P, McCallum M, Jani BD, McQueenie R, Lee D, Mair FS. Association between childhood maltreatment and the prevalence and complexity of multimorbidity: a cross-sectional analysis of 157,357 UK Biobank participants. J Comorb. 2020;10:2235042X10944344.

Chrousos GP. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5:374–81.

Boyce WT, Kobor MS. Development and the epigenome: the “synapse” of gene-environment interplay. Dev Sci. 2015;18:1–23.

Charmandari E, Kino T, Souvatzoglou E, Chrousos GP. Pediatric stress: hormonal mediators and human development. Horm Res. 2003;59:161–79.

Charmandari E, Achermann JC, Carel J-C, Soder O, Chrousos GP. Stress response and child health. Sci Signal. 2012;5:mr1.

Tsigos C, Chrousos GP. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:865–71.

Varghese FP, Brown ES. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in major depressive disorder: a brief primer for primary care physicians. Prim care companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:151–5.

Picard M, McEwen BS. Psychological stress and mitochondria: a systematic review. Psychosom Med. 2018;80:141–53.

Duchowny KA, Marcinek DJ, Mau T, Diaz-Ramierz LG, Lui L-Y, Toledo FGS, et al. Childhood adverse life events and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function. Sci Adv. 2024;10:eadj6411.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the researchers from the UKB for their generous provision of GWAS data, which significantly contributed to the advancement of this study.

Funding

This work received support from the AI-based Fertility Assessment and Intelligent Decision System for Perinatal Depressive Disorder Development (CSTB2023TIAD-KPX0051). The study funders/sponsors played no role in the design and execution of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zheng Zhang led the study design, participated in data collection, and was primarily responsible for the development of the manuscript. Hao Ren drafted and revised the manuscript. Rong Han supervised the initial analysis and contributed to the revision of the manuscript. Qiyin Li, Jiangyou Yu, and Yuan Zhao provided additional analytical insights and revisions to the manuscript. Cheng Gan, Keyi Liu, Liwei Tang, Yadong Peng, and Ying Liu contributed further to the drafting of the manuscript and provided critical intellectual input. Qinghua Luo, Haitang Qiu, and Chenggang Jiang supervised the final analysis, provided substantial intellectual revisions, and granted final approval for publication. All authors have approved the final manuscript and consented to its public dissemination.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used summary-level statistics from published studies and publicly available GWASs. No ethical approval and consent to participate was required for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Ren, H., Han, R. et al. Impact of childhood maltreatment on aging: a comprehensive Mendelian randomization analysis of multiple age-related biomarkers. Clin Epigenet 16, 103 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-024-01720-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-024-01720-z