Abstract

Background

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and COVID-19 preventive behaviours among people living with HIV during the pandemic has received little attention in the literature. To address this gap in knowledge, the present study assessed the associations between viral load, adherence to antiretroviral therapy and the use of COVID-19 prevention strategies during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a secondary analysis of data generated through an online survey recruiting participants from 152 countries. Complete data from 680 respondents living with HIV were extracted for this analysis.

Results

The findings suggest that detectable viral load was associated with lower odds of wearing facemasks (AOR: 0.44; 95% CI:0.28–0.69; p < 0.01) and washing hands as often as recommended (AOR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42–0.97; p = 0.03). Also, adherence to the use of antiretroviral drugs was associated with lower odds of working remotely (AOR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.38–0.94; p = 0.02). We found a complex relationship between HIV positive status biological parameters and adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures that may be partly explained by risk-taking behaviours. Further studies are needed to understand the reasons for the study findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Greater risk-taking attitudes and behaviour are commonly associated with poorer health outcomes [1]. Risk-takers typically place greater emphasis on immediate, usually gratifying, outcomes and less focus on longer-term outcomes, which may be positive but require a delay in experiencing the benefits [2,3,4,5]. Risk-takers value immediate rewards over distant rewards, with perceived value diminishing the further into the future it appears [6]. Referred to as delay-discounting, this is demonstrated when risk-takers choose smaller but more immediate rewards over larger but more distant rewards [7, 8].

Risk-taking is reflected in behaviours like high-risk sexual behaviour and substance use [9,10,11,12,13,14] and results from a combination of low-risk perception and high-risk propensity [15]. For example, low perception of risk for HIV is associated with engagement in activities such as having multiple sexual partners, early age of first sexual intercourse, unprotected sexual intercourse and inconsistent use of condoms, and not seeking treatment for sexually transmitted diseases [16, 17]. Low risk perception also inhibits the motivation to use and adhere to HIV prevention [18], delays the initiation of antiretroviral therapy for people living with HIV [19], and when on treatment, is associated with poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy [20]. Poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy is objectively assessed by viral load, or the number of copies of the HIV copies in one millilitre of blood. Similarly, perception of risk for COVID-19 can predict compliance with preventive behaviours and social distancing measures [21, 22]. Males, younger people and people with lower education status are more likely to have high-risk taking behaviours related to COVID-19 [15].

Because risk-taking is a behavioural expression of high-risk propensity [23], and this trait can manifest among people living with HIV as poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy, we posit that poor adherence will be associated with lower likelihood of COVID-19 prevention adoption. For people living with HIV, poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy leads to having detectable HIV viral loads [24]. The aim of this study therefore, was to explore these relationships by determining whether an association exists between viral load, adherence to antiretroviral treatment, and the use of COVID-19 prevention strategies.

Main text

This was a secondary analysis of data generated through an online survey that recruited study participants from 152 countries between July and December 2020. The details of the parent study, including participants’ recruitment process [25, 26] and the tool used to collect the data [27], have been previously published. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Public Health of the Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife, Nigeria (HREC No: IPHOAU/12/1557). Additional ethical approvals were attained from India (D-1791-uz and D-1790-uz), Saudi Arabia (CODJU-2006 F), Brazil (CAAE N° 38423820.2.0000.0010) and United Kingdom (13,283/10,570). Study participants provided consent before participating in the online survey.

In the parent study, 904 respondents self-reported as being HIV positive. Of those, data from 680 (75.2%) respondents with complete responses for the dependent, independent, and confounding variables were extracted for this study. Respondents self-reported as being HIV positive by indicating the condition on a checklist of 27 medical ailments.

The dependent variables for this study were the use of COVID-19 prevention strategies: physical distancing, wearing of facemasks, hands washing, and working remotely. Respondents were asked if they adopted any of these behaviour for use during the pandemic. Respondents could select more than one item if they adopted multiple preventive behaviours during the pandemic.

The independent variable were the viral load and adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Participants selected response to questions about viral load and adherence: (1) What is your HIV viral load (undetectable, detectable and do not know), and (2) Some people find that they sometimes forget to take their medications to manage their HIV. Did you miss any of your HIV medications during COVID-19 (Yes, No)? Participants who noted they did not know their HIV status were excluded from analyses;

Confounding variables considered included age at last birthday [28, 29], sex at birth (male, female, intersex, no response) [30, 31] educational status (No formal education, primary level, secondary level and tertiary level) and self-report of depression [32, 33]. Depression was assessed by asking respondents to indicate if they had experienced any of the 10 listed emotions during the pandemic, one of which was depression. Respondents who did not check the box were categorised as not having experienced depression during the pandemic. Depression has been shown to be associated with HIV infection and has increased in prevalence during the COVID-19 pandemic [34,35,36,37].

Four multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine the associations between the dependent and independent variables after adjusting for the confounding variables. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Statistical significance was set at 5%.

Results

Of the 680 respondents living with HIV in this study, 459 (67.5%) kept physical distance, 581 (85.4%) wore face masks, 548 (80.6%) washed hands as often as recommended, and 140 (20.6%) worked remotely during the pandemic. As can be seen in Tables 1 and 488 (71.8%) were virally suppressed, 529 (77.8%) adhered to the use of the antiretrovirals and 128 (18.8%) were depressed during the lockdown.

People living with HIV with a detectable viral load had lower odds of physical distancing, wearing facemasks, washing hands as often as recommended and working remotely. The association was, however, only significant for wearing facemasks (AOR: 0.44; 95% CI:0.28–0.69; p < 0.01) and washing hands as often as recommended (AOR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.42–0.97; p = 0.03) during the pandemic. Also, people living with HIV who adhered to the use of the antiretroviral drugs had statistically significant for lower odds of working remotely (AOR: 0.60; 95% CI: 0.38–0.94; p = 0.02).

Discussion

The results partly support our study hypothesis that poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (reflected by detectable viral load) will be positively associated with poorer use of COVID-19 preventive behaviours. The study findings suggest that people living with HIV who had detectable viral load and who poorly adhered to antiretroviral therapy were less likely to adhere to COVID-19 preventive measures though this was only significant for wearing facemasks and washing hands as often as recommended. On the contrary, people living with HIV who adhered to antiretroviral therapy were less like to working remotely.

Risk-taking propensity has been shown to be directly associated with poor mask-wearing and physical distancing behaviours [38]. Risk-taking has also been associated with increased risk for HIV infection [39], and lower engagement in sexual risk behaviours [40]. Study findings suggest that risk-taking related to HIV treatment may reinforce risk-taking for COVID-19 prevention [41]. However, on the contrary, we observed that people living with HIV who adhere to the use of antiretroviral therapy were less likely to work remotely. This result may reflect a compensatory behaviour whereby the regular wearing of facemasks and handwashing may be considered enough precautionary measure to outweigh the risk for contracting infection, and address the need to reduce self-isolation (working remotely). This postulation ggives credence to a risk compensation hypothesis [42].

The risk compensation hypothesis implies that persons experiencing a real or perceived change in the riskiness of an activity will alter their consumption of that activity to obtain a preferred combination of risk and reward [43]. We hypothesis that people living with HIV who adhere to the use of antiretroviral therapy, wear facemasks, wash hands as is regularly required and adhere to physical distancing measures may feel this is safe enough interventions to reduce their risk for contracting COVID-19 if they do not work remotely. A decision not to work remotely may be connected with a decision to avoid social isolation, a risk factor for loneliness [44] and a critical risk factor for poor adherence to ART [45] and mortality for people living with HIV [46].

Risk-taking and non-adherence with COVID-19 preventive measures may be an active or passive risk-taking behaviour which are associated with different personal tendencies [47]. The failure to wear face masks and not to wash hands as recommended may be a result of passive risk-taking behaviour while the decision not to work remotely results from active risk-taking behaviour [47]. Personality traits like having more self-control, reduces passive risk-taking because future consequences of their actions are taken into account when making decisions about taking risks [48]. Active risk-takers take the future into perspectives when taking decisions about risk [47].

Our prior study had indicated that people living with HIV were more likely not to keep physical distance, isolated/quarantined and worked remotely when compared with people not living with HIV suggesting that the community may have concerns with social isolation and thus, will take actions to promote social engagement [49]. The current study finding however, suggests that individual personality traits linked to risk-taking behaviours may mediate the link between the biological profile of people living with HIV (viral load and adherence to use of antiretroviral drugs) and poor compliance with COVID-19 preventive measures. Personality traits linked to passive risk-taking may mediate the association between wearing of facemasks and not washing hands as recommended and viral load status; and the traits associated with active risk-taking may mediate the association between working remotely and adherence with use of antiretroviral therapy. It is therefore important that people living with HIV are counselled on-on-one to understand decision-taking about the use of COVID-19 preventive measures, and supported to address concerns and risk.

We observe a complex relationship exists between HIV status and the use of COVID-19 preventive measures that can be partially explained by individual’s risk-taking decisions. We postulate that people living with HIV who have passive risk-taking propensity are less likely to adhere to COVID-19 preventive measures. However, irrespective of the risk-taking propensity, people living with HIV are less likely to adopt COVID-19 preventive measures that promote social isolation and its associated risk for their long-term health and wellbeing through a risk compensation decision-making process. This postulation needs to be tested.

Limitations

This was a cross-sectional study and so cause-effect deductions cannot be made. Also, the data were collected using a non-probability sampling methods which limits the generalisability of the study findings. Also, the study had no access to data on the socioeconomic status and changes in socioeconomic status of participants during the pandemic. In addition, we made deductions about the roles of risk-taking behaviours in moderating the findings. Discussions about risk-taking behaviours need to be taken with caution as the risk-taking behaviour of study participants was not measured objectively. HIV status was also self-reported with a risk for underestimation of the HIV positive status of respondents (about 15% of the global population do not know their HIV status) [50]. Also, the study did not account for the possible biases that the socio-economic status of respondents could introduce. The findings reported here needs further exploration.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

22 August 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06419-7

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral Therapy

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus infectious disease 2019

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

References

Defoe IN, Dubas JS, Figner B, van Aken MA. A meta-analysis on age differences in risky decision making: adolescents versus children and adults. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):48–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038088.

Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146(4):447–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/pl00005490.

Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: a meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(6):887–919. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887.

Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control participants: drug and monetary rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;5(3):256–62. https://doi.org/10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256.

Mitchell VW. Consumer perceived risk: conceptualisations and models. Eur J Mark. 1999;33:163–95. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEC1086-4415130402.

Madden GJ. In: Bickel WK, editor. Impulsivity: the behavioral and neurological science of discounting. American Psychological Association; 2010. https://doi.org/10.1037/12069-000.

Frederick S, Loewenstein G, O’Donoghue T. Time discounting and time preference: a critical review. J Econ Lit. 2002;40:351–401. https://doi.org/10.1257/002205102320161311.

Scholten H, Scheres A, de Water E, et al. Behavioral trainings and manipulations to reduce delay discounting: a systematic review. Psychon Bull Rev. 2019;26:1803–49. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-019-01629-2.

Buckner JD, Eggleston AM, Schmidt NB. Social anxiety and problematic alcohol consumption: the mediating role of drinking motives and situations. Behav Ther. 2006;3 7(4):381–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2006.02.007.

Hanby MSR, Fales J, Nangle DW, Serwik AK, Hedrich UJ. Social anxiety as a predictor of dating aggression. J interpers Violence. 2012;27(10):1867–88.

Kashdan TB, McKnight PE. The darker side of social anxiety: when aggressive impulsivity prevails over shy inhibition. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19(1):47–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359280.

Lorian CN, Grisham JR. The safety bias: risk-avoidance and social anxiety pathology. Behav Change. 2010;27(1):29–41. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.27.1.29.

Lorian CN, Mahoney A, Grisham JR. Playing it safe: an examination of risk-avoidance in an anxious treatment-seeking sample. J Affect Disord. 2010;141(1):63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.021.

Rahm-Knigge RL, Prince MA, Conner BT. Social interaction anxiety and personality traits predicting engagement in health risk sexual behaviors. J Anxiety Disord. 2018;5 7:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.05.002.

Breivik G, Sand TS, Sookermany AM. Risk-taking attitudes and behaviors in the norwegian population: the influence of personality and background factors. J Risk Res. 2020;23(11):1504–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1750455.

Lavra B. Determinant of individual AIDS risk perception: knowledge, behavioral control and social influence. MPIDR working paper. 2002. http://www.Demogr.mpg.de/papers/working/wp-2002-0297/9/2004.

Ford CA, James J, Susan GM, Philip EB, William CM. Perceived risk of chlamydia and gonococcal infection among sexually experienced young adults in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36(6):258–64. https://doi.org/10.1363/3625804.

Matson PA, Chung S-E, Sander P, Millstein SG, Ellen JM. The role of feelings of intimacy on perceptions of risk for a sexually transmitted disease and condom use in the sexual relationships of adolescent african–american females. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88(8):617–21.

Dovel K, Phiri K, Mphande M, et al. Optimizing test and treat in Malawi: health care worker perspectives on barriers and facilitators to ART initiation among HIV-infected clients who feel healthy. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1):1728830. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1728830.

Govere SM, Galagan S, Tlou B, Mashamba-Thompson T, Bassett IV, Drain PK. Effect of perceived HIV risk on initiation of antiretroviral therapy during the universal test and treat era in South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):976. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06689-1.

Cipolletta S, Andreghetti GR, Mioni G. Risk perception towards COVID-19: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(8):4649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19084649.

Aduh U, Folayan MO, Afe A et al. Risk perception, public health interventions, and Covid-19 pandemic control in sub-saharan Africa. J Public Health Afr. doi: https://doi.org/10.4081/jphia.2021.1622.

Yates FJ, Stone ER. The Risk Construct. In: Risk-Taking Behavior: Wiley Series in Human Achievement and Cognition, edited by Yates FJ. Chichester: Wiley. 1992.

Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Amaral CM, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission risks: implications for test-and-treat approaches to HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(5):271–7. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0309.

Nguyen AL, Brown B, Tantawi ME, et al. Time to Scale-up Research Collaborations to address the global impact of COVID-19 - a Commentary. Health Behav Policy Rev. 2021;8(3):277–80. https://doi.org/10.14485/hbpr.8.3.9.

Ellakany P, Zuñiga RAA, El Tantawi M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student’ sleep patterns, sexual activity, screen use, and food intake: a global survey. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0262617. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262617.

El Tantawi M, Folayan MO, Nguyen AL, et al. Validation of a COVID-19 mental health and wellness survey questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1509. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13825-2.

Ho FK, Petermann-Rocha F, Gray SR, et al. Is older age associated with COVID-19 mortality in the absence of other risk factors? General population cohort study of 470,034 participants. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241824. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241824.

Ghidei L, Simone MJ, Salow MJ, et al. Aging, antiretrovirals, and adherence: a meta-analysis of adherence among older HIV-infected individuals. Drugs Aging. 2013;30(10):809–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0107-7.

Heestermans T, Browne JL, Aitken SC, Vervoort SC, Klipstein-Grobusch K. Determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive adults in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1(4):e000125. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000125.

Galbadage T, Peterson BM, Awada J, Buck AS, Ramirez DA, Wilson J, Gunasekera RS. Systematic review and Meta-analysis of sex-specific COVID-19 clinical outcomes. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.00348.

Oginni OA, Oloniniyi IO, Ibigbami O, Ugo V, Amiola A, Ogunbajo A, et al. Depressive and anxiety symptoms and COVID-19-related factors among men and women in Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0256690. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0256690.

Zewudie BT, Geze S, Mesfin Y et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Depression and Associated Factors among Adult HIV/AIDS-Positive Patients Attending ART Clinics of Ethiopia: 2021. Depress Res Treat. 2021; 2021:8545934. doi: https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8545934.

Yuan K, Zheng YB, Wang YJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on prevalence of and risk factors associated with depression, anxiety and insomnia in infectious diseases, including COVID-19: a call to action. Mol Psychiatry. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01638-z.

Parisi CE, Varma DS, Wang Y, Vaddiparti K, Ibañez GE, Cruz L, Cook RL. Changes in Mental Health among People with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic: qualitative and quantitative perspectives. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(6):1980–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03547-8.

Wagner GJ, Wagner Z, Gizaw M, Saya U, MacCarthy S, Mukasa B, Wabukala P, Linnemayr S. Increased depression during COVID-19 Lockdown Associated with Food Insecurity and Antiretroviral Non-Adherence among people living with HIV in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(7):2182–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03371-0.

Rezaei S, Ahmadi S, Rahmati J, et al. Global prevalence of depression in HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2019;9(4):404–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2019-001952.

Byrne KA, Six SG, Anaraky RG, Harris MW, Winterlind EL. Risk-taking unmasked: using risky choice and temporal discounting to explain COVID-19 preventative behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0251073. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251073.

Lammers J, Van Wijnbergen S. Tinbergen Institute. HIV/AIDS, Risk Aversion and Intertemporal Choice. Technical report. 2007.

Lépine A, Treibich C. Risk aversion and HIV/AIDS: evidence from senegalese female sex workers. Soc Sci Med. 2020;256:113020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113020.

Noussair CN, Trautmann ST, Van De Kuilen G. Higher order risk attitudes, demographics, and financial decisions. Rev Econ Stud. 2014;81:325–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdt032.

Houston DJ, Richardson LE. Risk compensation or risk reduction? Seatbelts, state laws, and traffic fatalities. Soc Sci Q. 2007;88:913–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2007.00510.x.

Dulisse B. Methodological issues in testing the hypothesis of risk compensation. Accid Anal Prev. 1997;29(3):285–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0001-4575(96)00082-6.

Peplau LA, Perlman D. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D, editors. Perspectives on loneliness. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, Research and Practice. New York: John Wiley; 1982. pp. 1–17.

Turan B, Smith W, Cohen MH, et al. Mechanisms for the negative Effects of internalized HIV-Related stigma on antiretroviral therapy adherence in women: the mediating roles of social isolation and depression. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(2):198–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000000948.

Marziali ME, McLinden T, Card KG, et al. Social isolation and mortality among people living with HIV in British Columbia. Can AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):377–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-03000-2.

Keinan R, Idan T, Bereby-Meyer Y. Compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: active vs. passive risk takers. Judgement and decision making. 2021;16(1):20–35.

Keinan R, Bereby-Meyer Y. Perceptions of active versus passive risks, and the effect of personal responsibility. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2017;43(7):999–1007.

Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, Brown B, et al. Differences in COVID-19 preventive behavior and food insecurity by HIV Status in Nigeria. AIDS Behav. 2022 Mar;26(3):739–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03433-3.

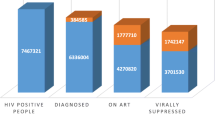

UNAIDS, Global HIV, AIDS statistics — Fact sheet. &. 2022. Accessible at: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed: 2nd September, 2022.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the participants who provided data and contributed their time to make this study possible.

Funding

Authors provided personal funds to conduct this study. A.L.N. was supported by a grant from the NIH/NIA (K01 AG064986-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O.F conceived the study. The Project was managed by M.O.F., and A.L.N. Data curating was done by N.M.A. Data analysis was conducted by R.A.A.Z. MOF developed the first draft of the document. R.A.A.Z, N.M.A., P.E., I.E.I, M.F., F.B.L, Z.K., J.L. J.I.V. and A.L.N. all read the draft manuscript and made inputs prior to the final draft. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of the current study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at Institute of Public Health of the Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife, Nigeria (HREC No: IPHOAU/12/1557) as the lead partner for this study. The protocol was in accordance with international and national research guidelines. All participants provided written informed consent before taking the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Jorma I. Virtanen is an Associate Editor, BMC Public Health. Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan is a Senior Editor Board members with BMC Oral Health. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised to include a correct Table 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Folayan, M.O., Abeldaño Zuñiga, R.A., Aly, N.M. et al. Differences in adoption of COVID-19 pandemic related preventive behaviour by viral load suppression status among people living with HIV during the first wave of the pandemic. BMC Res Notes 16, 90 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06363-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06363-6