Abstract

Few studies have examined preventative behaviour practices with respect to COVID-19 among people living with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). Using a cross-sectional survey from a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canadian HIV Trials Network study (CTN 328) of people living with HIV on vaccine immunogenicity, we examined the relationships between participant characteristics and behavioural practices intended to prevent COVID-19 infection. Participants living in four Canadian urban centers were enrolled between April 2021–January 2022, at which time they responded to a questionnaire on preventative behaviour practices. Questionnaire and clinical data were combined to explore relationships between preventive behaviours and (1) known COVID-19 infection pre-enrolment, (2) multimorbidity, (3) developing symptomatic COVID-19 infection, and (4) developing symptomatic COVID-19 infection during the Omicron wave. Among 375 participants, 49 had COVID-19 infection pre-enrolment and 88 post-enrolment. The proportion of participants reporting always engaging in preventative behaviours included 87% masking, 79% physical distancing, 70% limiting social gatherings, 65% limiting contact with at-risk individuals, 33% self-isolating due to symptoms, and 26% self-quarantining after possible exposure. Participants with known COVID-19 infection pre-enrolment were more likely to self-quarantine after possible exposure although asymptomatic (65.0% vs 23.4%, p < 0.001; Chi-square test). Participants with multiple comorbidities more likely endorsed physical distancing (85.7% vs 75.5%, p = 0.044; Chi-square test), although this was not significant in logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, number of household members, number of bedrooms/bathrooms in the household per person, influenza immunization, and working in close physical proximity to others. Overall, participants reported frequent practice of preventative behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, many people have faced challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic including loss of income and employment, worsened mental health, and decreased access to medical care [1, 2]. The pandemic has also amplified the intersectional vulnerabilities faced by many people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). For example, among people living with HIV in the United States, African–Americans and those with low incomes were more likely to suffer complications following severe COVID-19 infection [3]. People living with HIV may also have difficulty placing trust in the health care system; in one cohort of African–American people living with HIV in the United States, 97% of individuals endorsed at least one COVID-19 mistrust belief and half had COVID-19 vaccine-specific mistrust [4]. By contrast, people living with HIV may be more engaged in COVID-19 preventative behaviours or vaccine uptake than the general population [5, 6]. People living with HIV have known history of activism and high level of community involvement in research. Considering this, more study of COVID-19 preventative behaviours is needed within the population of people living with HIV that can guide new policies and enhance vaccination success.

Since the first global COVID-19 immunization campaign was launched, attitudes and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine in people living with HIV have been much more extensively researched than behavioural practices (e.g. mask-wearing, avoiding large gatherings). In this study, we sought to understand the relationships between preventative behaviours and COVID-19 infection in a multi-centre, cross-sectional study of people living with HIV in Canada. We addressed this topic through four questions:

-

(1)

Does previous known COVID-19 infection influence preventative behaviours among PLWH?

-

(2)

Is participant multimorbidity (presence of multiple comorbidities) associated with preventative behaviour practices among PLWH?

-

(3)

Are preventative behaviour practices, living in a crowded space, and working in close proximity to others associated with COVID-19 transmission among PLWH?

-

(4)

Are preventative behaviour practices and/or uptake of COVID-19 vaccination associated with developing symptomatic COVID-19 infection during the highly contagious Omicron wave among PLWH?

Methods

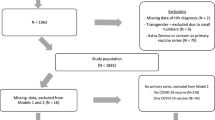

Our study population comprised people living with HIV living in Montréal, Ottawa, Toronto and Vancouver, Canada aged at least 16 years who had received no more than two COVID-19 immunizations at the time of enrolment. The immunization requirement was part of the inclusion criteria for a separate study on COVID-19 vaccine immunogenicity [7]. Participants were engaged in HIV care and were recruited through participating medical clinics. Participants were enrolled between April 2021 and January 2022. At enrolment, demographic data were collected, together with the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF) Standardized Core Survey Data Elements questionnaire [8] [Additional file 1]. This cross-sectional questionnaire captured self-reported preventative behaviours including masking, physical distancing, avoiding crowds, limiting physical greetings (hugs and handshakes), avoiding visits with vulnerable individuals, self-isolating if sick, and self-quarantining if suspected exposure. Frequency of behaviours was ranked on a five-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘always’, with only those reporting ‘always’ included as engaging in a specific behaviour. HIV viral load, CD4 cell count was obtained from samples taken within 12 months of enrolment. COVID-19-specific antibody testing was performed from samples obtained at enrolment and at subsequent visits within the study period. Participant comorbidities including obesity, cardiac disease, lung disease, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and other significant comorbidities were also recorded at the time of enrolment using the patient questionnaire and chart review.

From the total study population, responses from appropriate subsets of participants were analyzed to address each of the four aforementioned questions, as described in Table 1. Statistical analysis was performed to assess for significant differences between demographics and CITF questionnaire responses with t-test, chi-square test, and Fisher exact test used as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess for associations between outcomes and predictors of interest while accounting for other factors that might confound the association based on prior knowledge. No imputation was performed to impute the missing data as this is mainly a descriptive study. Conduct of this study was approved by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN) Scientific Review Committee and Community Advisory Committee, as well as by each site’s Research Ethics Board as previously outlined [7].

Results

Among the 375 participants enrolled in the study, the mean age was 52.0 years (standard deviation 13.3 years) with a range of 19.7–83.5 years. Detailed characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. The median duration of HIV infection was 17.0 years with interquartile range 7.0–24.0 years. The overall proportion of participants with well-controlled HIV infection (defined as CD4 ≥ 350 cells/mm3, suppressed HIV viral load), and low number of comorbidities (one or fewer) was 52%. One-third of participants (28.1%) had two or more comorbidities. Most participants (69.1%) had achieved more than a secondary school education (secondary school education comprises schooling up to age 17–18 in Canada). A total of 49 participants had documented COVID-19 infection before study enrolment based on either self-report (n = 25, 51%) or laboratory testing (n = 24, 49%). Eighty-eight participants contracted COVID-19 infection during the study period, up until April 2022, based on either of self-report (n = 54, 61%) and laboratory testing (n = 34, 39%). Of note, the vaccine immunogenicity study is still ongoing so the total number of COVID-19 infections during the total study period is currently unknown. Overall, preventative behaviours were frequently practiced in the cohort, with 87% masking in public, 79% distancing, 70% avoiding large gatherings, and 65% limiting contact with vulnerable persons.

Does previous known COVID-19 infection influence preventative behaviours?

To address this question, we excluded individuals with positive serum COVID-19 antibody testing (presumed prior infection) but no knowledge of prior infection (n = 24). A detailed explanation of the participant subsets used in each of the four questions is found in Fig. 1. Participants reporting prior known COVID-19 infection (based on self-report) (n = 25) were more likely to identify as non-white (p < 0.001), less likely to have stable HIV infection (32.0% vs 53.5%, p = 0.039), have more household members (p < 0.001), fewer household bedrooms and bathrooms per person (p = 0.021 and p = 0.006, respectively), and were more likely to be employed in health care (p < 0.001) than those not reporting prior infection. There were no significant differences in the other demographic factors between the prior known infection and non-infected groups. In response to the preventative behaviours survey, participants with prior known COVID-19 were more likely to self-quarantine when thought to have been exposed to COVID-19 but were not symptomatic (p < 0.001) and self-isolate when thought to been infected with COVID-19 (p = 0.021). These differences remained statistically significant after adjusting for age, sex and the aforementioned patient characteristics that were different between groups (aOR = 6.72 [95% CI: 1.98, 22.84], p = 0.002 and 3.50 [95% CI: 1.09, 11.21], p = 0.035 respectively). These were the only significant differences in preventative behaviours between groups.

Is participant multimorbidity associated with preventative behaviour practices?

Participants in the multimorbidity group were more likely to be older (mean age 59.2 years vs 49.0 years, p < 0.001), live in a household with fewer members (p = 0.020), have more bedrooms and bathrooms in the household per person (p = 0.019 and p = 0.008, respectively), usually get an influenza immunization (p = 0.045), and less likely to be performing paid or unpaid work in close physical proximity to others (p = 0.035). They were more likely to be vaccinated with four doses against COVID-19 by September 2022 (33.7% vs 16.7%, p = 0.001). In response to the preventative behaviours survey, participants in the multimorbidity group were more likely to be practicing physical distancing (85.7% vs 75.5%, p = 0.044). This difference, however, was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for participant characteristics (age, sex, race, number of household members, number of bedrooms and bathrooms in the household per person, uptake of influenza immunization and performing paid or unpaid work in close physical proximity to others) (aOR = 1.74 [95% CI: 0.84, 3.58], p = 0.140), and no other significant differences in preventative behaviours between groups were noted.

Are preventative behaviour practices, living in a crowded space, and working in close proximity to others associated with COVID-19 infection?

The participants in the COVID-19 infection group were more likely to have fewer bedrooms per person (mean 1.0 vs 1.3, p = 0.006). There were no identified differences in the proportion of participants performing paid or unpaid work in close physical proximity to others between those with and without COVID-19 infection (28.2% vs 32.9%, p = 0.429). There were no identified differences in preventative behavior practices between those with and without baseline COVID-19 infection.

Are preventative behaviour practices and/or uptake of COVID-19 vaccination associated with developing symptomatic COVID-19 infection during the highly contagious Omicron wave?

In Canada, the Omicron wave began in late November 2021 [9]. Participants in the Omicron infection group were more likely to have been tested for COVID-19 at some point before study enrolment (p = 0.015). There was no statistical difference in Omicron infection rate by COVID-19 vaccination status at the start of the Omicron wave (26.9% versus 16.0% for those who received 3 vaccine doses versus less than 3 doses, p = 0.065). The finding was the same after adjusting for age, sex, race, multimorbidity, number of household members, number of bedrooms and bathrooms in the household per person and performing paid/unpaid work in close physical proximity to others (aOR = 1.84 [95% CI: 0.80, 4.22], p = 0.150). There were no significant differences in preventative behaviours between those sustaining COVID-19 infection during the Omicron wave and those not infected during this time period.

Discussion

Using data from our cohort of people living with HIV, we examined four questions regarding COVID-19 preventative behaviours. Another study done in the Canada in general population assessed determinants of adherence to major coronavirus preventive behaviours, including demographics, attitudes and concerns and showed that adherence to COVID-19 prevention behaviours was worse among men, younger adults, and workers, and deteriorated over time [10]. We did not observe these differences. Among those having prior known infection with COVID-19, the only difference noted in preventative behaviours was an increased likelihood of self-quarantining after a suspected exposure. Participants engaged in work with close physical proximity to others did not report different preventative behaviours or COVID-19 infection proportions. Multimorbidity was associated with more physical distancing, although there were also multiple demographic factors noted to be different in this group (increased vaccine uptake and less crowding at home and work). In the highly contagious Omicron wave, we did not observe any differences in vaccine uptake or preventative behaviours between those who did and did not sustain infection. Overall, preventative behaviours were practiced in a high proportion of the cohort, with 87% masking in public, 79% distancing, 70% avoiding large gatherings, and 65% limiting contact with vulnerable persons. In a 2020 Canadian survey cohort of the general population, over 70% always reported masking in public and staying home when sick while over 50% avoided large gatherings; only 40% engaged in physical distancing [11].

Preventative behaviours including masking, physical distancing, and limiting gatherings have had high uptake globally in people living with HIV. In a South African cohort of people living with HIV, 80% changed one or more activities based on public health recommendations [12]. One United States cohort of 149 people living with HIV reported engaging in an average of 2.8 (SD 1.4, range 0–5) physical distancing behaviours [13]. In a cohort of 545 primarily male Indonesian people living with HIV, 70% reported practicing preventative behaviours [2]. Among 376 Rwandan people living with HIV, factors associated with the increased practice of preventative behaviours included duration of antiretroviral therapy and female gender [14]. Increasing age had a consistent association with preventative behaviours in one rapid review of the general population (not specific to those living with HIV) in developed countries, while health status and education did not show consistent effects [15].

Limited data exist on the effects of prior COVID-19 infection on preventative behaviours or on the influence of working in close physical proximity to others on COVID-19 behaviours in people living with HIV. Greater vaccine uptake among those with multimorbidity and/or older age has been reported in a South African cohort of people living with HIV [12]. In contrast, a Chinese cohort of people living with HIV was less likely to receive COVID-19 vaccination [16]. Fear of disclosure of HIV status at vaccination appointments was reported in this later assessment which may explain the heterogeneity of findings across reports.

We observed no difference in vaccination status between participants sustaining Omicron infection and those not infected. We note that studies in the general population have shown a less protective effect of original vaccine formulations against the Omicron variants although behavioural differences during the Omicron wave may have also played a role in our cohort [17].

Our study has several limitations: the entire cohort was participating in COVID-19 vaccination programs to some degree and had easy access to provincial and federal public health programs for testing and education. This may limit the generalization of our results to settings where public health infrastructure is not available to disseminate information and vaccines. It also encapsulates behaviours for only a portion of people living with HIV who consented to vaccination. Data was collected only at the beginning of Omicron wave resulting in small number of participants being infected by COVID-19 Omicron variant and therefore may not be fully generalizable to Omicron and subsequent waves.

In summary, our Canadian cohort of people living with HIV reported high rates of preventative behaviour practices. We found differences in preventative behaviours among those with prior COVID-19 infection and in those with multimorbidity suggesting these are key motivating factors in facilitating preventative behaviours.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CIHR:

-

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- CTN:

-

Canadian HIV Trials Network

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

References

O’Brien KK, Bayoumi AM, Carusone SC, Davis AM, Aubry R, Avery L, et al. Disability and self-care living strategies among adults living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res Sq. 2021;rs.3.rs-868864.

Karjadi TH, Maria S, Yunihastuti E, Widhani A, Kurniati N, Imran D. Knowledge, attitude, behavior, and socioeconomic conditions of people living with HIV in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. HIVAIDS Auckl NZ. 2021;14(13):1045–54.

Weiser JK, Tie Y, Beer L, Neblett Fanfair R, Shouse RL. Racial/ethnic and income disparities in the prevalence of comorbidities that are associated with risk for severe COVID-19 among adults receiving HIV care, United States, 2014–2019. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2021;86(3):297–304.

Bogart LM, Ojikutu BO, Tyagi K, Klein DJ, Mutchler MG, Dong L, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2021;86(2):200–7.

Folayan MO, Abeldaño Zuniga RA, Abeldaño GF, Quadri MFA, Jafer M, Yousaf MA, et al. Is self-reported depression, HIV status, COVID-19 health risk profile and SARS-CoV-2 exposure associated with difficulty in adhering to COVID-19 prevention measures among residents in West Africa? BMC Public Health. 2022;10(22):2057.

Holt M, MacGibbon J, Bavinton B, Broady T, Clackett S, Ellard J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake and hesitancy in a national sample of Australian gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(8):2531–8.

Costiniuk CT, Singer J, Langlois MA, Kulic I, Needham J, Burchell A, et al. CTN 328: immunogenicity outcomes in people living with HIV in Canada following vaccination for COVID-19 (HIV-COV): protocol for an observational cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12): e054208.

COVID-19 Immunity Task Force Field Studies Working Party. COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF) Standardized Core Survey Data Elements questionnaire. COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (CITF). Available from: https://www.covid19immunitytaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Core-Elements_English-New.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2022.

Ulloa AC, Buchan SA, Daneman N, Brown KA. Estimates of SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant severity in Ontario, Canada. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1286–8.

Lavoie KL, Gosselin-Boucher V, Stojanovic J, Voisard B, Szczepanik G, Boyle JA, et al. Determinants of adherence to COVID-19 preventive behaviours in Canada: results from the iCARE Study. medRxiv; 2021. p. 2021.06.09.21258634. Available from: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.09.21258634v1. Accessed 22 Aug 2023.

Lang R, Atabati O, Oxoby RJ, Mourali M, Shaffer B, Sheikh H, et al. Characterization of non-adopters of COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions through a national cross-sectional survey to assess attitudes and behaviours. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):21751.

Govere-Hwenje S, Jarolimova J, Yan J, Khumalo A, Zondi G, Ngcobo M, et al. Willingness to accept COVID-19 vaccination among people living with HIV in a high HIV prevalence community. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(22):1239.

Berman M, Eaton LA, Watson RJ, Andrepont JL, Kalichman S. Social distancing to mitigate COVID-19 risks is associated with COVID-19 discriminatory attitudes among people living with HIV. Ann Behav Med Publ Soc Behav Med. 2020;54(10):728–37.

Iradukunda PG, Pierre G, Muhozi V, Denhere K, Dzinamarira T. Knowledge, attitude, and practice towards COVID-19 among people living with HIV/AIDS in Kigali, Rwanda. J Community Health. 2021;46(2):245–50.

Moran C, Campbell DJT, Campbell TS, Roach P, Bourassa L, Collins Z, et al. Predictors of attitudes and adherence to COVID-19 public health guidelines in Western countries: a rapid review of the emerging literature. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2021;43(4):739–53.

Yao Y, Chai R, Yang J, Zhang X, Huang X, Yu M, et al. Reasons for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Chinese people living with HIV/AIDS: structural equation modeling analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8(6): e33995.

Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;NEJMoa2119451.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants for their time and commitment. In addition, we thank study coordinators and study nurses: Florian Bobeuf, Claude Vertzagias, Lina Del Balso, Nathalie Paisible, Guillaume Theriault, Hansi Peiris, Lianne, Thai, Rosemarie Clarke, Erin Collins, Nadia Ohene-Adu, Aaron Dyks, Hope LaPointe, and Jill Jackson; data manager: Elisa Lau; laboratory staff: Suzanne Samarani, Tara Mabanga, Yulia Alexandrova, Ralph-Sydney Mboumba Bouassa, Erik Pavey, Stephanie Burke-Schinkel, Danielle Dewar-Darch, Justino Hernandez Soto, Abishek Xavier, Yuchu Dou, Sarah Speckmaier, Maggie Duncan, Hanwei Sudderuddin and F. Harrison Omondi. The authors also thank physicians who assisted with recruitment.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Vaccine Surveillance Reference group and the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force (2122-HQ-000075). It was also supported by the CIHR Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN 328).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.T.C., C.L.C., J.S, J.N., and B.V. generated the study questions. C.T.C., C.L.C., S.W., and M.H. supervised data collection. T.L. processed the data and performed statistical analysis. K.H. reviewed the existing literature. K.H., B.V., and C.T.C. drafted the manuscript, refined the study questions, and designed the tables. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Conduct and publication of this study was approved by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Canadian HIV Trials Network (CTN) Scientific Review Committee and Community Advisory Committee, as well as by each site’s (Montréal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Vancouver) Research Ethics Board.

Competing interests

The authors do not have other relevant employment or financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

HIV-COV CITF CDE baseline questionnaire.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hammond, K., Lee, T., Vulesevic, B. et al. Preventative behaviours and COVID-19 infection in a Canadian cohort of people living with HIV. AIDS Res Ther 20, 73 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00571-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00571-7