Abstract

Background

Non-seminomatous germ cell tumours make up about 40 % of all germ cell tumours, which in turn are the most common tumours in men aged 15–44 years. Low risk stage I non-seminomatous germ cell tumours, which are confined to the testes, are commonly treated by orchiectomy and surveillance. Up to 20 % of patients with this diagnosis relapse, usually within 1–2 years of follow up, but very rarely after more than 5 years. The most common sites of relapse are the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, the mediastinum, and the lungs. We describe a case of relapse in the prostate over 20 years after initial diagnosis, which has not been described in the literature so far.

Case presentation

This report presents a 49-year-old white British man with relapsed testicular non-seminomatous germ cell tumour 22 years after initial treatment with orchidectomy only. He relapsed with a prostatic mass, haematospermia and back pain. His prostate specific antigen levels were within normal range. Alpha feto-protein and lactate dehydrogenase levels were elevated, and his human chorionic gonadotrophin levels were normal. A biopsy confirmed undifferentiated malignant tumour, shown immunohistochemically to be a yolk sac tumour. The patient was initially treated with bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin chemotherapy, but developed bleomycin-related pulmonary side effects after two cycles. His treatment was changed and he completed four cycles of chemotherapy by receiving two cycles of etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin. Post treatment blood tumour markers were normal, but a follow up computed tomography showed a mass in the base of the prostate, the trigone and the left distal ureter which was surgically resected. The histology from the surgical resection was of necrotic tissue. The patient is now in follow up at 3 years after treatment with no evidence of residual disease on computed tomography. His Alpha feto-protein, beta human chorionic gonadotrophin and lactate dehydrogenase levels are normal.

Conclusions

Very late relapse in stage I non-seminomatous germ cell tumours is extremely rare and the prostate is a highly unusual site of relapsed disease. For diagnosis of late relapse, this case confirms the value of serum biomarkers in germ cell tumours, in particular non-seminomatous germ cell tumours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-seminomatous germ cell tumours (NSGCTs) constitute about 40 % of all germ cell tumours, which in turn are the most common tumours in men aged 15–44 years [1]. After orchidectomy, the risk of relapse in stage I disease can be predicted by histological examination of the orchidectomy specimen for the presence of lymphovascular invasion. If this is absent the relapse risk is 20 %; if it is present the risk is 50 % [2–4]. This risk is accumulated mainly in the first 2 years. Later relapse is extremely rare [5–7]. The retroperitoneum is the most common site of relapse, followed by mediastinal, lung and pleural, and rarely pelvic lymph nodes [8]. In the case of relapse, the cure rates are 98–99 % due to the high sensitivity of NSGCTs to platinum based chemotherapy. Adjuvant retroperitoneal lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy have been shown to reduce relapse risk, but have side effects and cost implications, and are considered mainly in high-risk patients [9]. Post treatment surveillance comprises of history, examination, measurement of the tumour markers beta human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta HCG) and alpha feto-protein (AFP), and radiological surveillance with chest radiographs and computed tomography (CT) at regular intervals. Radiological investigations and measurements of tumour markers, in cases with initially raised marker levels, are the most important parts of the surveillance protocol [10]. There is no consensus regarding the number or frequency of CT scans on surveillance though results from the TE08 trial suggest 2 CT scans of the abdomen at 3 and 12 months of follow-up may be sufficient [11, 12].

In contrast to the large majority of cases, we present a case of relapsed stage I NSGCT more than 20 years after orchidectomy without adjuvant therapy. This case is further noteworthy due to the highly unusual site of relapse within the prostate.

Case presentation

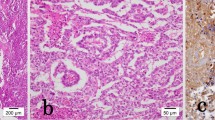

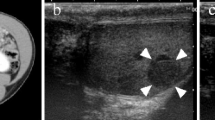

A 49-year-old white British man presented to his General Practitioner and afterwards a Urologist with spontaneously resolving haematospermia, normal prostate specific antigen (PSA) and normal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the prostate. His past medical history was remarkable for stage I NSGCT which was treated with orchidectomy 21 years previously. He took no regular medication. A year after resolution of the haematospermia he developed nocturia, poor urinary flow, and a feeling of pressure on his rectum. This was associated with severe back pain, for which he had started simple analgesia. Examination and ultrasound investigation of the remaining testis was normal. His PSA level was in the normal range at 1.11 microg/L but his AFP level at that stage was grossly elevated at 7787 ng/mL (normal range <10 ng/mL) with an lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 486 U/L (normal range 0–250 U/L). HCG and free beta HCG levels were normal at less than 2 and less than 0.2 U/L, respectively. CT at that point demonstrated a pelvic mass with associated enlarged pelvic lymph nodes, mild left hydronephrosis, and multiple pulmonary metastases up to a diameter of 1.7 cm. An MRI was subsequently performed to better define the local anatomy prior to surgery. MRI demonstrated an extensive prostatic tumour extending into bladder (Fig. 1a, b), seminal vesicles, rectum and left ureter causing hydronephrosis. The total volume of the prostate was elevated at 113 mL. Histopathology from bladder biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of an undifferentiated malignant tumour that from its immunoprofile (AFP, PLAP and CD117 positive, CD30 and OCT 3/4 negative), was diagnosed as metastatic yolk sac tumour (Fig. 2). Due to the non-pulmonary visceral metastases in the prostate his disease fell into the high risk category and treatment with four cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy was initiated. He received a nephrostomy for decompression of the hydronephrosis and completed the first two cycles of BEP chemotherapy, but then developed evidence of bleomycin-related lung changes on chest radiography and CT. His treatment was changed to etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin (VIP) chemotherapy and he completed another two cycles for a total of four cycles of chemotherapy. He did not have any long term effects from the bleomycin.

T2-weighted magnetic resonance images. a, b Axial and coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance images demonstrate a heterogeneous high signal lesion in the left seminal vesicle and prostate gland. There is a urinary catheter in situ. The lesion is markedly different to the low signal lesion typically found in primary prostatic carcinoma

Histopathological characterisation. Analysis was performed on paraffin-embedded tissue using haematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained sections. a ×10 magnification showing benign prostatic glands (upper part of picture) and undifferentiated tumour with sheets of cells and small cystic spaces (lower part of picture). b ×40 magnification showing a normal benign prostatic gland (lower part of picture) and undifferentiated tumour (upper part of picture)

All tumour markers were within the normal range after completion of chemotherapy. A CT 3 months into follow up, however, showed a residual mass of 2.7 cm in the base of the prostate, the trigone and the left distal ureter which was surgically resected. The excision specimen showed necrotic tissue and small amounts of normal prostate tissue and fibrosis, but no evidence of tumour cells. The tumour markers at this point had completely normalised. The patient is now in follow up at 36 months after treatment with no evidence of residual disease on CT. His AFP, beta HCG and LDH levels are normal.

Conclusion

The incidence of relapse in stage I NSGCT later than 2 years after surgery is very low. No large data sets are available on late relapse, but published case series suggest, that the majority of relapses in non-seminoma patients occur in the first 10 years of follow up, with the retroperitoneum being the most common site of relapse, followed by the mediastinum, the lung and pleura, and rarely the pelvic lymph nodes [5, 6, 8, 13–16]. There are a few cases published for relapse of germ cell tumors >20 years after diagnosis [17, 18]. Reviewing the pathology of relapses later than 2 years, Michael et al. found teratoma was the most commonly identified histology followed by yolk sac. Unusual types of yolk sac tumor were found to cause differential diagnostic problems with non-germ cell carcinomas, especially as there were many different sites of relapse [14].

Two case reports are similar to this case, Arafat et al. describe a case involving a patient with stage I NSGCT who relapsed with a retroperitoneal mass after 27 years [19] and Lattouf et al. a case of stage I NSCGT who presented with a seminal vesicle relapse after 20 years [20]. For seminoma combined with yolk-sac tumour, late relapse after 43 years of surveillance has been described [21]. Notably, the published literature on case series in seminoma suggests that late relapse beyond 10 years is more common than for non-seminomas [7, 8, 22].

The patient described in this report had relapsed disease after 22 years from a stage I NSGCT that had been treated with orchidectomy and surveillance. Therefore, this case is distinct from the majority of reports listed above due to its stage, protracted time to relapse and site of relapse.

The tumour marker alpha fetoprotein was grossly elevated at relapse and the tumour was visible on radiological investigation. Current guidelines do not cover in detail the protocol for continuous follow up of patients with stage I non-seminoma due to the lack of quality evidence [23, 24]. Surveillance is more rigorous at the start as most relapses are early-median time to relapse for NSGCT is around 6–9 months. This includes monitoring of the tumour markers and radiological investigations [23, 24].

One case report is, of course, insufficient to inform the treatment and follow up guidelines. It does, however, confirm the value of tumour marker in diagnosis of very late relapsed non-seminoma. Furthermore, it establishes evidence that NSGCT can recur more than 20 years after initial treatment, and this can be in highly unusual sites such as the prostate. It also highlights the need to note the history of a previous germ cell tumour when late metastatic disease occurs, as the histological features of such tumours (particularly yolk sac tumours post chemotherapy) may not be typical of the primary tumour and may therefore be misinterpreted histologically.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Abbreviations

- NSGCT:

-

non-seminomatous germ cell tumour

- PSA:

-

prostate specific antigen

- AFP:

-

alpha feto-protein

- LDH:

-

lactate dehydrogenase

- HCG:

-

human chorionic gonadotrophin

- CT:

-

computed tomography

- BEP:

-

bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin chemotherapy

- VIP:

-

etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin chemotherapy

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

References

Bray F, Richiardi L, Ekbom A, Pukkala E, Cuninkova M, Møller H. Trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality in 22 European countries: continuing increases in incidence and declines in mortality. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:3099–111.

Alexandre J, Fizazi K, Mahé C, Culine S, Droz JP, Théodore C, Terrier-Lacombe MJ. Stage I non-seminomatous germ-cell tumours of the testis: identification of a subgroup of patients with a very low risk of relapse. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:576–82.

Cullen MH, Stenning SP, Parkinson MC, Fossa SD, Kaye SB, Horwich AH, Harland SJ, Williams MV, Jakes R. Short-course adjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: a Medical Research Council report. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1106–13.

Freedman LS, Parkinson MC, Jones WG, Oliver RT, Peckham MJ, Read G, Newlands ES, Williams CJ. Histopathology in the prediction of relapse of patients with stage I testicular teratoma treated by orchidectomy alone. Lancet. 1987;2:294–8.

George DW, Foster RS, Hromas RA, Robertson KA, Vance GH, Ulbright TM, Gobbett TA, Heiber DJ, Heerema NA, Ramsey HC, Thurston VC, Jung S-H, Shen J, Finch DE, Kelley MR, Einhorn LH. Update on late relapse of germ cell tumor: a clinical and molecular analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:113–22.

Shahidi M, Norman AR, Dearnaley DP, Nicholls J, Horwich A, Huddart RA. Late recurrence in 1263 men with testicular germ cell tumors. Multivariate analysis of risk factors and implications for management. Cancer. 2002;95:520–30.

Blanke CD, Delgalvis SC, Nichols GR. Late recurrence of seminoma. South Med J. 1997;90:653–5.

Oldenburg J, Alfsen GC, Waehre H, Fosså SD. Late recurrences of germ cell malignancies: a population-based experience over three decades. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:820–7.

Horwich A, Shipley J, Huddart R. Testicular germ-cell cancer. Lancet. 2006;367:754–65.

Cunniffe NG, Robson J, Mazhar D, Williams MV. Clinical examination does not assist in the detection of systemic relapse of testicular germ cell tumour. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2012;24:39–42.

Rustin GJ, Mead GM, Stenning SP, Vasey PA, Aass N, Huddart RA, Sokal MP, Joffe JK, Harland SJ, Kirk SJ. Randomized trial of two or five computed tomography scans in the surveillance of patients with stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis: Medical Research Council Trial TE08, ISRCTN56475197—the National Cancer Research Institute Testis Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1310–5.

Van As NJ, Gilbert DC, Money-Kyrle J, Bloomfield D, Beesley S, Dearnaley DP, Horwich A, Huddart RA. Evidence-based pragmatic guidelines for the follow-up of testicular cancer: optimising the detection of relapse. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1894–902.

Baniel J, Foster RS, Einhorn LH, Donohue JP. Late relapse of clinical stage I testicular cancer. J Urol. 1995;154:1370–2.

Michael H, Lucia J, Foster RS, Ulbright TM. The pathology of late recurrence of testicular germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:257–73.

Nolan L, Wheater M, Kirby J, Simmonds P, Mead G. Late relapse (>2 years) on surveillance in stage I non-seminomatous germ cell tumours; predominant seminoma only histology. BJU Int. 2010;106:1648–51.

Sharp DS, Carver BS, Eggener SE, Kondagunta GV, Motzer RJ, Bosl GJ, Sheinfeld J. Clinical outcome and predictors of survival in late relapse of germ cell tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5524–9.

Kohei N, Kinoshita H, Kamoto T, Terai A, Kakehi Y, Ogawa O. Late relapse of testicular cancer 21 years after first complete remission: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2008;54:39–42.

Pavic M, Meeus P, Treilleux I, Droz JP. Malignant teratoma 32 years after treatment of germ cell tumor confined to testis. Urology. 2006;67:846.e11–3.

Arafat W, Albany C, Ulbright TM, Foster R, Einhorn LH. Very late relapse of germ cell tumor as a teratoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg case reports. 2014. doi:10.1093/jscr/rju051.

Lattouf J-B, Mc Cormack M, Yelle L, Hadjeres R, Saad F. Recurrence of a non-seminomatous germ cell tumor in the seminal vesicle 20 years after initial diagnosis and treatment. Can J Urol. 2004;11:2350–1.

Mukhtar S, Beatty J, Agrawal S, Christmas TJ, Jameson C, Huddart RA. Germ cell tumour: late recurrence after 43 years. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e24–6.

Thai E, Leonardi F, Soliani P, Silini EM. Late recurrence of a seminoma of the testis with a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma component. Int J Surg Pathol. 2012;20:396–400.

Krege S, Beyer J, Souchon R, Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bamberg M, Bodrogi I, Bokemeyer C, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Classen J, Clemm C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Culine S, Daugaard G, De Mulder PHM, De Santis M, de Wit M, de Wit R, Derigs HG, Dieckmann K-P, Dieing A, Droz J-P, Fenner M, Fizazi K, Flechon A, Fosså SD, del Muro XG, Gauler T, Geczi L, et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus group (EGCCCG): part I. Eur Urol. 2008;53:478–96.

Krege S, Beyer J, Souchon R, Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bamberg M, Bodrogi I, Bokemeyer C, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Classen J, Clemm C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Culine S, Daugaard G, De Mulder PHM, De Santis M, de Wit M, de Wit R, Derigs HG, Dieckmann K-P, Dieing A, Droz J-P, Fenner M, Fizazi K, Flechon A, Fosså SD, del Muro XG, Gauler T, Geczi L, et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG): part II. Eur Urol. 2008;53:497–513.

Authors’ contributions

DM, BT, DN, JR and NA were involved in the care of the patient. DM, JR and NA were involved in the oncology treatment. BT and DN were involved in the surgical treatment. AS was responsible for reviewing the radiology in the case and AW for the histology. TJ, SW and DM conceived of the case report and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

There are no acknowledgements to be made.

Funding

TJ was supported by an Academic Clinical Lectureship grant as part of the Wellcome Trust Translational Medicine and Therapeutics program (University of Cambridge grant code RJAG/076).

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Janowitz, T., Welsh, S., Warren, A.Y. et al. Prostatic relapse of an undifferentiated teratoma 24 years after orchidectomy. BMC Res Notes 8, 524 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1445-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1445-9