Abstract

Background

Erlotinib is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor, which is an effective treatment for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), especially those harboring activating EGFR mutations. A previous phase III trial suggested that patients with EGFR wild-type (EGFR-wt) NSCLC or elderly patients with disease progression after cytotoxic chemotherapy might benefit from erlotinib monotherapy. However, few studies have prospectively evaluated the efficacy and safety of second- or third-line erlotinib monotherapy for elderly patients with EGFR-wt advanced or recurrent NSCLC.

Methods

Pretreated patients aged ≥70 years with EGFR-wt stage IIIB/IV NSCLC or those with postoperative recurrence were enrolled and received oral erlotinib at a dose of 150 mg/day until disease progression. Primary outcome was the objective response rate (ORR). Secondary end points included the disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and toxicity profile.

Results

This study was terminated early because of the results from a Japanese phase III trial (DELTA trial). Sixteen patients were enrolled between April 2010 and May 2013. The median age was 78 years (range 70–84 years). Six patients were female. Five patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0. Eleven (69%) patients had adenocarcinoma. Fifteen (94%) patients were treated with erlotinib as a second-line therapy. The ORR was 0% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0–17.1]. DCR was 56.3% (95% CI 33.2–76.9). The median PFS and OS were 1.7 months (95% CI 1.3–2.2) and 7.2 months (95% CI 5.6–8.7), respectively. The most commonly occurring adverse events included acneiform eruption (31.3%) and skin rash (25.0%). One patient developed grade 3 interstitial lung disease, which improved following steroid therapy.

Conclusions

In pretreated elderly patients with advanced or recurrent EGFR-wt NSCLC, daily oral erlotinib was well tolerated; however, administration of the drug should not be considered as a second line therapy.

Trial registration: University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry UMIN000004561 (Date of registration: November 15th, 2010)

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In industrialized countries, increasing longevity and declining fertility rates are shifting the age distribution of populations toward older age groups. Thus, the prevalence and incidence of various diseases are increasing, and approximately 50% of patients at diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) are >70 years old [1]. Studies on various treatments including vinorelbine [2], gemcitabine [3], and docetaxel [4] as first-line therapy for this population have been conducted. However, the clinical outcomes in terms of tumor response and survival were not satisfactory because of the limited efficacy of these monotherapies. Prospective studies of second-line treatments for this patient population are limited. Thus, exploration of an optimal treatment strategy for elderly patients with NSCLC, as either first-line or second-line therapy is required.

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) treatment, which is less toxic than cytotoxic chemotherapy, is the standard treatment option for pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC [5, 6]. In addition, first-line gefitinib, an EGFR-TKI, is an effective and feasible treatment for elderly advanced NSCLC patients with activating mutations who were relatively ineligible for standard chemotherapy [7].

BR.21 was a randomized phase III trial comparing EGFR-TKI erlotinib with the best supportive care for pretreated patients with advanced NSCLC. The post hoc subgroup analysis of the trial showed that elderly and EGFR status unknown patients who underwent treatment with erlotinib acquired substantial survival benefit and improved quality of life [8]. Further subgroup analysis showed that the patients with EGFR wild-type (EGFR-wt) may also benefit from erlotinib [9]. However, prospective investigation of the clinical benefit of erlotinib for pretreated elderly patients with EGFR-wt advanced or recurrent NSCLC has not been reported.

We conducted a prospective phase II trial to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of erlotinib in pretreated elderly patients with EGFR-wt advanced or recurrent NSCLC.

Methods

Patients and methods

Eligibility criteria included: age ≥70 years; pathologically or cytologically proven NSCLC; measurable tumor sites according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) guideline version 1.1; an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2; no activating EGFR gene mutations (exon 18, 19, 20 and 21); history of 1–2 regimens of systemic chemotherapy; stage IIIB or IV NSCLC, or postoperative recurrence; EGFR-TKI treatment naïve; and appropriate organ function. Required laboratory criteria were white blood cell count >3,000/mm3, neutrophil count >1,500/mm3, platelet count >100,000/mm3, hemoglobin >9.0 g/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) <1.5-fold the upper limit of normal (ULN), total bilirubin <1.5 mg/dL, and serum creatinine <1.5-fold the ULN.

Patients who had received chemotherapy within 4 weeks of trial registration, those who had undergone chest radiotherapy within 12 weeks of trial registration, and those with interstitial lung disease (ILD) were excluded.

Baseline pretreatment evaluations included a physical examination, chest and abdominal computed tomography (CT), brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and radionuclide bone scintigraphy or positron emission tomography. All images were taken within 4 weeks of trial registration.

All enrolled patients provided written informed consent. This study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating institution. The main Institutional Review Board that approved our trial was that of Fukushima Medical University, with an approval number of 917 on February 26th, 2009. This study was subsequently registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry; identification number, UMIN 000004561.

Assessment of tumor EGFR gene mutation status

EGFR gene mutation analysis was performed using invasive signal amplification reaction using a structure-specific 5′ nuclease with a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product (PCR-invader) [10].

Assessment of antitumor activity, survival measures, and toxicity

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 was used to evaluate tumor response. CT to assess target or non-target lesions was conducted every 4 weeks (MRI for brain, where appropriate, was also conducted). A complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all target and non-target lesions. A partial response (PR) was defined as at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the diameters of the target lesions compared with the baseline sum of the longest diameters, with no progression of non-target lesions and no new lesions [11]. Stable disease (SD) was defined as no disease progression or tumor growth for at least 6 weeks. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as a 20% increase of the sum of measurable lesions, unequivocal progression of non-measurable lesions, or the appearance of new disease despite treatment. Objective response rate (ORR) was defined as the proportion of patients whose best response was either CR or PR in the intent-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of the patients whose best response was CR, PR or SD in the ITT analysis. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from registration to objective tumor progression or death from any cause, and overall survival (OS) was the time from registration until death. Responses were confirmed by the central review board. All toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3.0).

Treatment regimen

Erlotinib was administrated orally at a dose of 150 mg/day, and was discontinued if patients developed ≥grade 2 toxicities. For skin disorders, patients who recovered from grade 2 toxicities could restart erlotinib on the same dose, whereas in those who improved from grade 3 to grade 1 skin disorders, the dose was reduced to 100 mg/day. Erlotinib treatment was discontinued in cases where the following conditions occurred: (1) disease progression; (2) withdrawal of informed consent; (3) development of grade 4 non-hematologic toxicity; and (4) any ILD grade. Local therapies such as thoracic surgery/radiotherapy and other systemic anti-cancer treatments were not permitted during the trial.

Statistical analyses

To determine the number of patients required to power the study, we assumed the lower limit of ORR to be 10.0% based on the ORR of erlotinib for elderly patients with unknown or wild-type status of EGFR mutation, which was reported previously as 7.0–10.0% [8, 9, 12, 13], and that an ORR of 25.0% in eligible patients would indicate potential usefulness. With an alpha value of 0.05 and 80% power, we estimated that a total of 40 patients would be needed.

The PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the response rates were evaluated using the Clopper–Pearson method. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

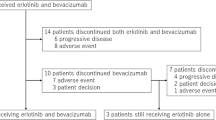

This trial was terminated when the results of the DELTA trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting in 2013 [14]. Between April 2010 and May 2013, 16 patients were enrolled. CONSORT diagram is shown in Figure 1 (Additional file 1). All patients assessed for eligibility were assigned to receive erlotinib and analyzed. The patients’ baseline characteristics are listed in Table 1. The median age was 78 years (range 70–84), six patients were female, and five patients had a performance status of 0. Eleven patients had adenocarcinoma, two patients had squamous cell carcinoma and one patient had adenosquamous carcinoma. Fifteen (94%) patients were treated with erlotinib as a second-line therapy.

Efficacy

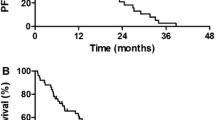

All 16 patients were evaluable for response. The ORR and DCR were 0.0% (95% CI 0.0–17.1%) and 56.3% (95% CI 33.2–76.9%), respectively (Table 2). With a median follow-up time of 7.4 months (range 1.3–32.0 months), 15 (94%) patients experienced disease progression or died. Median PFS and OS were 1.7 months (95% CI 1.3–2.2 months) and 7.2 months (95% CI 5.6–8.7 months), respectively (Figure 2).

Safety

The incidence of treatment-related adverse events is summarized in Table 3. The most common adverse event was grade 1/2 acneiform eruption (31.3%, n = 5 patients), followed by skin rash (25.0%, n = 4 patients). All patients with adverse skin reactions continued erlotinib, except for those with grade 2 toxicity that required temporary discontinuation according to the protocol. Grade 3/4 non-hematologic toxicities occurred in two patients, one with elevated AST and ALT levels (6.3%), and one who developed ILD (6.3%). The patient with ILD received systemic steroid therapy and showed full recovery, although erlotinib treatment was discontinued. The patient with elevated AST/ALT levels, recovered on erlotinib discontinuation, and did not recommence treatment.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first prospective trial to evaluate erlotinib monotherapy for pretreated elderly patients with EGFR-wt NSCLC, although the study was terminated early. In this trial, the ORR was lower than expected.

Previous clinical trials reported the effectiveness of erlotinib for patients with EGFR-wt NSCLC. Subgroup analysis of BR.21 demonstrated that 7% of non-squamous EGFR-wt NSCLC patients responded to erlotinib and 8% of elderly, EGFR status- unknown NSCLC patients responded to erlotinib [8, 9]. The SATURN trial investigated the efficacy of erlotinib as a switch maintenance therapy following four cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy. Compared with the placebo in the trial, erlotinib prolonged the survival of patients with EGFR-wt NSCLC [12.4 vs 8.7 months, HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.48–0.87); p = 0.0041] [15, 16]. In a sharp contrast, several other prospective studies [17, 18] demonstrated that the ORR of erlotinib monotherapy in a second-line setting was <5%. In the present study, we believe there are several reasons for the low ORR. First, the study evaluated elderly patients, who most likely have potentially poorer organ function and a lower performance status compared with younger patients. Second, EGFR status was determined in this study by PCR-invader assay, whereas direct sequencing was used in the BR.21 trial. The sensitivity and specificity of direct sequencing has recently been confirmed as being lower than those of PCR-based methods [19–21]. The high specificity of the PCR-invader assay may be associated with a more accurate assessment of negative EGFR mutation status, resulting in a lower ORR in the current study.

The slow accrual of this study was because of the release of data from the TAILOR trial [22]. In addition, the study was finally terminated following the disclosure of data from the DELTA trial [14], which recruited Japanese NSCLC patients following the TAILOR trial. In both studies, erlotinib failed to show any improvement in PFS compared with docetaxel in pretreated advanced EGFR-wt NSCLC patients aged ≥20 years. A recent meta-analysis also demonstrated that in patients with advanced EGFR-wt NSCLC, conventional chemotherapy was associated with better improvement of PFS compared with first-generation EGFR-TKIs such as gefitinib and erlotinib [23]. Therefore, we believe early termination of this study was appropriate.

The frequency of skin-related adverse events in the current study was comparable to the frequency of skin disorders reported in a large-scale erlotinib-treated Japanese cohort [24]. In the current study, all adverse events improved with short-term discontinuation, and all but two patients with grade 3/4 events recommenced erlotinib treatment. The large-scale Japanese study reported that the incidence of ILD was 4.5%, and ILD-related death occurred in 1.6% of patients. The higher incidence of ILD in the current study was most likely because of the small patient population. However, there were no cases of ILD-related death.

Conclusions

Erlotinib monotherapy was well tolerated in pretreated elderly patients with EGFR-wt advanced or recurrent NSCLC. However, erlotinib should not be considered as a second line therapy for pretreated EGFR-wt elderly NSCLC patients.

References

Thakkar JP, McCarthy BJ, Villano JL (2014) Age-specific cancer incidence rates increase through the oldest age groups. Am J Med Sci 348:65–70

Gridelli C (2001) The ELVIS trial: a phase III study of single-agent vinorelbine as first-line treatment in elderly patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Elderly Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Italian Study. Oncologist 6(Suppl. 1):4–7

Gridelli C, Perrone F, Gallo C, Cigolari S, Rossi A, Piantedosi F et al (2003) Chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Multicenter Italian Lung Cancer in the Elderly Study (MILES) phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:362–372

Kudoh S, Takeda K, Nakagawa K, Takada M, Katakami N, Matsui K et al (2006) Phase III study of docetaxel compared with vinorelbine in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of the West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Trial (WJTOG 9904). J Clin Oncol 24:3657–3663

Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, Tan EH, Hirsh V, Thongprasert S et al (2005) Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 353:123–132

Johnson JR, Cohen M, Sridhara R, Chen YF, Williams GM, Duan J et al (2005) Approval summary for erlotinib for treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after failure of at least one prior chemotherapy regimen. Clin Cancer Res 11:6414–6421

Inoue A, Kobayashi K, Usui K, Maemondo M, Okinaga S, Mikami I et al (2009) First-line gefitinib for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harboring epidermal growth factor receptor mutations without indication for chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 27:1394–1400

Wheatley-Price P, Ding K, Seymour L, Clark GM, Shepherd FA (2008) Erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in the elderly: an analysis of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol 26:2350–2357

Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, Liu N et al (2008) Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol 26:4268–4275

Olivier M (2005) The invader assay for SNP genotyping. Mutat Res 573:103–110

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247

Jackman DM, Yeap BY, Lindeman NI, Fidias P, Rabin MS, Temel J et al (2007) Phase II clinical trial of chemotherapy-naive patients > or = 70 years of age treated with erlotinib for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 25:760–766

Tamura T, Nishiwaki Y, Watanabe K, Nakagawa K, Matsui K, Takahashi T et al (2007) Evaluation of efficacy and safety of erlotinib as monotherapy for Japanese patients with advanced non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC); integrated analysis of two Japanese phase II studies: P3-148. J Thorac Oncol 2:S742–S743

Okano Y, Ando M, Asami K, Fukuda M, Nakagawa H, Ibata H et al (2013) Randomized phase III trial of erlotinib (E) versus docetaxel (D) as second- or third-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) who have wild-type or mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR): Docetaxel and Erlotinib Lung Cancer Trial (DELTA). J Clin Oncol 31(Suppl. 15): 8006.abstr

Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, Szczesna A, Juhasz E et al (2010) Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 11:521–529

Coudert B, Ciuleanu T, Park K, Wu YL, Giaccone G, Brugger W et al (2012) Survival benefit with erlotinib maintenance therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) according to response to first-line chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 23:388–394

Yoshioka H, Hotta K, Kiura K, Takigawa N, Hayashi H, Harita S et al (2010) A phase II trial of erlotinib monotherapy in pretreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer who do not possess active EGFR mutations: Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group trial 0705. J Thorac Oncol 5:99–104

Kobayashi T, Koizumi T, Agatsuma T, Yasuo M, Tsushima K, Kubo K et al (2012) A phase II trial of erlotinib in patients with EGFR wild-type advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 69:1241–1246

Eberhard DA, Giaccone G, Johnson BE (2008) Biomarkers of response to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Working Group: standardization for use in the clinical trial setting. J Clin Oncol 26:983–994

Goto K, Satouchi M, Ishii G, Nishio K, Hagiwara K, Mitsudomi T et al (2012) An evaluation study of EGFR mutation tests utilized for non-small-cell lung cancer in the diagnostic setting. Ann Oncol 23:2914–2919

Naoki K, Soejima K, Okamoto H, Hamamoto J, Hida N, Nakachi I et al (2011) The PCR-invader method (structure-specific 5′ nuclease-based method), a sensitive method for detecting EGFR gene mutations in lung cancer specimens; comparison with direct sequencing. Int J Clin Oncol 16:335–344

Garassino MC, Martelli O, Bettini A, Floriani I, Copreni E, Lauricella C et al (2012) TAILOR: a phase III trial comparing erlotinib with docetaxel as the second-line treatment of NSCLC patients with wild-type (wt) EGFR. J Clin Oncol 30(Suppl 480S): LBA7501.abstr

Lee JK, Hahn S, Kim DW, Suh KJ, Keam B, Kim TM et al (2014) Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors vs conventional chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer harboring wild-type epidermal growth factor receptor: a meta-analysis. JAMA 311:1430–1437

Nakagawa K, Kudoh S, Ohe Y, Johkoh T, Ando M, Yamazaki N et al (2012) Postmarketing surveillance study of erlotinib in Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): an interim analysis of 3488 patients (POLARSTAR). J Thorac Oncol 7:1296–1303

Author’s contributions

HM and HY contributed to the drafting of this manuscript and data collection. HM, KK, HY, and TI contributed to the study design and statistical analysis. HY, KA, KH, SS, KO, YI, TI, and YK enrolled patients. KA and YT reviewed the manuscript. MM provided final approval of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients who participated in this study, and their families. We also thank Dr. Atsuro Fukuhara, Dr. Naoko Fukuhara and Dr. Takefumi Nikaido (Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Fukushima Medical University) for their contributions to this study. No external funding was acquired.

Compliance with ethical guidelines

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

CONSORT 2010 checklist of information to include when reporting a randomised trial.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Minemura, H., Yokouchi, H., Azuma, K. et al. A phase II trial of erlotinib monotherapy for pretreated elderly patients with advanced EGFR wild-type non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Res Notes 8, 220 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1214-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1214-9