Abstract

Introduction

The transition to metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO) is driven by the limited expandability of adipose tissue (AT). Familial Partial Lipodystrophy type 2 (FPLD2) is an alternative model for AT dysfunction that is suitable for comparison with obesity. While MUO is associated with low-grade systemic inflammation, studies of inflammation in FPLD2 have yielded inconsistent results. Consequently, comparison of inflammation markers between FPLD2 and obesity is of great interest to better understand the pathophysiological defects of FPLD2.

Objective

To compare the levels of inflammatory biomarkers between a population of patients with FPLD2 due to the same ‘Reunionese’ LMNA variant and a population of patients with obesity (OB group).

Methods

Adiponectin, leptin, IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 plasma levels were measured by enzyme-linked immuno assays for 60 subjects with FPLD2 and for 60 subjects with obesity. The populations were closely matched for age, sex, and diabetic status.

Results

Metabolic outcomes were similar between the two populations. Adiponectinemia and leptinemia were lower in the FPLD2 group than in the OB group (p < 0.01 for both), while MCP-1 levels were higher in the FPLD2 than in the OB group (p < 0.01). Levels of other inflammatory markers were not significantly different.

Conclusions

Insulin-resistant patients with FPLD2 and obesity share common complications related to AT dysfunction. Inflammatory biomarker analyses demonstrated that MCP-1 levels and adiponectin levels differ between patients with FPLD2 and patients with obesity. These two AT pathologies thus appear to have different inflammatory profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Systemic low-grade inflammation in obesity is implicated as a primary marker of adipose tissue (AT) dysfunction (1), which then leads to adverse cardio-metabolic complications (2). In metabolically unhealthy obesity (MUO), cytokine profile changes include an increase in pro-inflammatory markers like IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) with a concomitant decrease in anti-inflammatory markers like adiponectin (2–3). IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1 and adiponectin are secreted by adipocytes and can be used to measure inflammation in AT (1–4), and the limited expandability of this AT is a key feature of the transition from metabolically healthy obesity to MUO. Familial Partial Lipodystrophy type 2 (FPLD2) [MIM#151,660] is a suitable alternative model to better understand the consequences of the limited expandability of AT (5). FPLD2 is a rare genetic disease caused by the ubiquitous expression of pathogenic LMNA variants in all cells (6,7). Previous conflicting studies have suggested that FPLD2 is associated with a pro-inflammatory state (8–11). In patients bearing the ‘typical’ LMNA p.(Arg482Trp/Gln) variants, hs-CRP and TNF-α plasma levels were significantly elevated compared levels BMI- and sex-matched controls (8,10). However, for other inflammatory biomarkers such as resistin, IL-6 and IL-1β, systemic levels did not differ between groups (8–9). These conflicting results might be explained, at least in part, by the small sample size of this rare disease group, or by the high heterogeneity of the control group. Interestingly, as described for obesity, adiponectinemia was lower in FPLD2 patients compared to healthy subjects (8,9,12). Both FPLD2 and obesity shared the same complications related to insulin resistance and inflammation, including diabetes, dyslipidaemia, cardiovascular disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (13,14). Therefore, a comparison of inflammatory biomarkers between subjects with obesity and FPLD2 is of great interest.

The aim of the present study was to measure and compare the levels of key AT-related inflammatory biomarkers in subjects with obesity to levels in FPLD2 patients having the same pathogenic LMNA ‘Reunionese’ variant.

Materials and methods

Patients

We described in Reunion Island (France), the largest cohort worldwide of subjects with FPLD2 caused by a unique LMNA pathogenic variant p.(Thr655Asnfs*49) (NM_170707.4:c.1961dup) called ‘Reunionese’ variant (15). This ‘Reunionese’ variant consists of a G insertion at codon 654 in prelamin-A-specific exon 11 (NM_170707.4:c.1961dup) (16). Consequently, the prevalence of FPLD2 in Reunion is particularly high (around 1/8,500 inhabitants) (15). We measured inflammatory biomarkers in the serum of 60 patients diagnosed with FPLD2 and genotyped for the ‘Reunionese’ variant (FPLD2 group). Six patients were homozygous, and 54 patients were heterozygous for the variant. We measured the same biomarkers in the serum of 60 patients with a body mass index (BMI) corresponding to a overweight (BMI > 25 kg/m2) or obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) diagnosis (OB group). The groups were matched for age, sex, and diabetic status as closely as possible. The exclusion criteria were: age under 18 years, a familial partial lipodystrophy not attributed to the “Reunionese” variant. All patients provided written informed consents for molecular analyses. The study was performed according to local and European Union ethical rules (N°ID-RCB: 2021-A00105-36) and has been approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Sud Mediterranee IV, France.

Data collection

Patient screening and follow-up were performed at the Reunion Island Lipodystrophy Competence Centre, part of the French National Reference Network for Rare Diseases of Insulin Secretion and Insulin Sensitivity. The attending physician conducted patient interviews and clinical examinations to collect medical history, demographic data, and clinical data. The clinical data collected were age, gender, total body weight, BMI and percentage body fat mass (%BFM) and treatment history for diabetes and dyslipidaemia. The biological data collected included HbA1c, insulin resistance determined by the homeostasis model assessment index (HOMA-IR), hs-CRP, total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) and kidney parameters: glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the CKD-EPI equation and urine albumin/creatinine ratio was measured on a urine sample. The presence of NAFLD was assessed by liver ultrasound. Levels of the liver enzymes aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were measured. Liver fibrosis was assessed non-invasively. FIB-4 scores were calculated with the following formula: [age (years) × AST (IU/L)]/[platelet count (109/L) × ALT (IU/L)]. APRI score s were calculated with the following formula: [AST (IU/L)/platelet count (109/L)] × 100). The liver stiffness measurement (LSM) was performed using transient elastometry (Fibroscan 430, Echosens SAS, Paris, France). High-risk fibrosis was defined by FIB4 > 3.25, and/or APRI > 1.5 and/or F3-F4 fibrosis stage as assessed by the LSM. Hypertension was defined by blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg or the use of antihypertensive drugs. Cardiac / vascular atherosclerotic diseases were defined by the presence of ischemic coronary disease or stroke, carotid stenosis or lower limb atherosclerosis as determined by Doppler ultrasound.

Blood collection

Samples of serum were collected in 2 mL tubes without additive, aliquoted and stored at -80 °C prior to analysis. Levels of adiponectin, leptin, IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1 were measured by ELISA. Assays were performed on 100 µL samples in 96-well plate for IL-6, MCP-1 (Human IL-6 and MCP-1/CCL2 Uncoated ELISA Kits Invitrogen ThermoFischer Scientific USA) and TNF-α (human TNF-α uncoated ELISA Kit Ebioscience USA) or diluted with purified water for leptin (dilution 1:20) (human leptin coated ELISA Kit Ray Biotech USA) and adiponectin (dilution 1:2500) (human adiponectin Coated ELISA Kit TECO Medical Group Switzerland). The sensitivity of the assays was 2.0 pg/mL for leptin and IL-6, 2.3 pg/mL for TNF-α, 7.0 pg/mL for MCP-1 and < 0.6 ng/mL for adiponectin. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a FLUOstar Omega Microplate Reader (BMG LABTECH GmbH Germany).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were described using frequency and percentages. Quantitative variables were described using medians and interquartile ranges. Bivariate comparisons of qualitative variables were assessed with the Chi-Square or the Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Quantitative variables were compared with the Mann and Whitney test. Due to the multiplicity of tests, the False Discovery Rate method correction was applied. P values were two-tailed and considered significant when lesser than 0.05. Pearson correlations were measured between the different metabolic and anthropometric parameters: a linear correlation was strong if the correlation coefficient |r|> 0.7; medium if 0.5 <|r|< 0.7 ; and low if 0.1 <|r|< 0.5 =. Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.3.

Results

FPLD2 and OB subjects displayed similar metabolic complications

The FPLD2 and OB groups were similar in age and sex composition (Table 1). As expected, weight, BMI and %BFM were lower in subjects with FPLD2 than in OB subjects (all p < 0.01). The two groups had a similar median HOMA-IR index, above 2.5, indicating an insulin-resistant state. The two groups did not differ in pre-diabetes or diabetes prevalence, age at onset of diabetes, or glycemic control (HbA1c). However, TG levels were significantly higher (p ≤ 0.01) and HDL-C levels significantly lower (p = 0.02) in the FPLD2 group compared to the OB group, despite similar use of lipid-lowering therapy. The prevalences of NAFLD, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and micro/macro-albuminuria were statistically similar between the groups.

The FPLD2 and OB groups with diabetes were similar in age and sex composition (Table 2). As expected, weight and BMI were lower in subjects with FPLD2 and diabetes than in OB subjects (all p < 0.01). Median age at onset of diabetes and glycemic control (HbA1c) did not differ between the two groups. There was no difference in regard of the type of anti-diabetic treatment used between the two populations. Nine FPLD2 subjects and 4 subjects in OB group were under insulin therapy. Finally, there was no significant difference in micro-angiopathic (micro-/macro-albuminuria, peripheral neuropathy and retinopathy) and macro-angiopathic / cardiovascular complications.

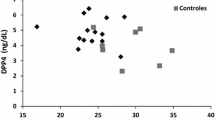

Inflammatory markers profiles differ between subjects with FPLD2 and obesity

Adiponectinemia and leptinemia were lower in FPLD2 patients than in OB subjects (p < 0.01 for both) (Fig. 1A and B), while MCP-1 levels were significantly higher in the FPLD2 group (p < 0.01). No differences were observed in levels of hs-CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α between the groups. As expected, leptin levels showed a significant positive correlation with BMI and %BFM in FPLD2 (respectively R = 0.71, p < 0.001 and R = 0.58, p < 0.001) and OB subjects (R = 0.45, p < 0.001 and R = 0.47, p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2A). We also found that hs-CRP levels correlated positively with BMI and %BFM in FPLD2 (R = 0.48, p < 0.001 and R = 0.48, p < 0.001, respectively) and OB subjects (R = 0.55, p < 0.001 and R = 0.52, p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2B). Adiponectin, MCP-1, IL-6 and TNF-α levels were not correlated with BMI and %BFM in either group. In the FPLD2 group, adiponectinemia was positively correlated with HDL-C level (R = 0.37, p = 0.003) and negatively associated with the HOMA-IR (R = -0.31, p = 0.018) (Fig. 2C and D). In OB group, HOMA-IR was negatively associated with adiponectinemia (R = -0.36, p = 0.004) and positively correlated with hs-CRP level (R = 0.29, p = 0.037). Data did not indicate any other significant correlation between HDL-C level or HOMA-IR and other inflammatory biomarkers (Additional File 1).

Significant Pearson correlations between the different metabolic and anthropometric parameters in patients with FPLD2 due to the “Reunionese” LMNA variant (n = 60) and in patients with obesity (n = 60). (HOMA-IR) homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, (%BFM) % of body fat mass was assessed by Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis

Discussion

In this study, we measured inflammatory biomarkers between two distinct insulin resistant populations related to AT dysfunction: one with FPLD2 and the other with obesity. Results show that subjects with FPLD2 had significantly lower leptin and adiponectin levels and higher MCP-1 levels in comparison with subjects with obesity, despite similar metabolic complications. The prevalence of diabetes, used as a matching criterion, could not be analysed. Data also show no statistical difference in the levels of other cytokines including IL-6, TNF-α and hs-CRP between both groups.

Adiponectin is an interesting surrogate marker of insulin sensitivity. Adiponectin is also an anti-inflammatory adipocytokine due to its ability to attenuate pro-inflammatory signalling pathways (17). In our study, as reported previously, both FPLD2 and OB groups had extremely low levels of adiponectin (8,9,12). However, hypoadiponectinemia was significantly more pronounced in FPLD2 potentially as a consequence of adipocytes apoptosis and oxidative stress induced by the accumulation of mutated prelamin in FPLD2 (7) in addition to insulin resistance. Hypoadiponectinemia has been associated with endothelial tissue dysfunction, which is unsurprising given that adiponectin provides a protective barrier against monocyte adhesion and thus protection against subsequent endothelial cells inflammation (18). Thus, in patients with lipodystrophy, hypoadiponectinemia could aggravate endothelial cells dysfunction induced by the accumulation of mutated pre-lamin in these cells and increased oxidative stress (11). Vascular abnormalities associated with a poor metabolic environment may be responsible for the extremely high risk of cardio-vascular diseases in this population. Interestingly, in lipoatrophic mice model, the glycaemic status was improved with recombinant adiponectin (19). This finding suggests that adiponectin could be a promising treatment for FPLD2 in improving metabolic and vascular functions. Interestingly, MCP-1 levels were particularly highly elevated in our FPLD2 group. Adiponectin has been reported to have a reducing effect on MCP-1 production in adipocytes (20) and endothelial cells (21). MCP-1 is produced by a variety of cell types (macrophages, endothelial cells, adipocytes) and is incriminated in vascular dysfunction through the recruitment of immune cells and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In obesity, MCP-1 production increases in proportion to visceral adiposity expansion (22). In lipodystrophy, the overexpression of p.R482W prelamin-A in transfected human coronary artery endothelial cells was shown to increase MCP-1 expression significantly (11). In lipodystrophy, the overexpression of p.R482W prelamin-A in transfected human coronary artery endothelial cells was shown to increase MCP-1 expression significantly (11). We found no evidence of a relationship between MCP-1 and adiponectin levels in the Dunnigan population (data not shown). Nonetheless, considering the interactions already identified between these two biomarkers, it may be prudent to investigate in appropriate cellular and animal models whether MCP-1 overexpression in endothelial and adipose tissues in FPLD2 may be related to hypoadiponectinemia in FPLD2.

In a previous study, we analyzed glucose homeostasis in a sample of 102 patients with the ‘Reunionese’ FPLD2 variant and compared measures with those from 22 unaffected adult relatives (23) with similar BMI values. Median leptin levels in unaffected subjects did not differ from leptin levels in the ‘Reunionese’ FPLD2 subjects (23). The leptin levels observed in this previous study (23) were similar to those observed in the present FPLD2 group. Furthermore, our results also show that leptinemia in Dunnigan subjects was significantly lower than in OB subjects, underscoring the strong relationship between leptin production and body fat mass. In patients with FPLD2, recombinant leptin treatment clearly improves weight management and insulin sensitivity while reducing free fatty acid (FFA) levels (24) which is consistent with the impact of hypoleptinemia on these metabolic abnormalities.

Our work is the first to measure inflammatory biomarkers in the largest cohort worldwide of FPLD2 patients with the pathogenic ‘Reunionese’ variant of LMNA. We found that systemic levels of IL-6, hs-CRP, and TNF-α in FPLD2 subjects were comparable to those in obese, insulin-resistant patients. For these two insulin-resistant AT diseases, no human study has compared inflammatory biomarkers. These findings could imply that FPLD2 is a pro-inflammatory illness, but such an inference should be viewed with caution. The switch to MUO in hypertrophic AT is characterized by deterioration of the immuno-modulatory system, especially in visceral AT, and an imbalanced profile with an excess of pro-inflammatory immune cells (25). Many inflammatory biomarkers are secreted by adipocytes and immune cells in the AT environment, including hs-CRP, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. There are undoubtedly more markers that contribute to the development of MUO (1–4,26). In contrast, the development of MUO is associated with a reduction in the expression of anti-inflammatory and/or insulin-sensitizer cytokines (adiponectin, IL-10) (26,27).

Inflammation in obesity is strongly linked to insulin resistance; and inflammatory markers interfere with insulin signaling pathways through activation of JNK and MAPK or IKK/NF-κB pathways (28,29). As with obesity, lipodystrophy appears to be associated with changes that include a decline in immuno-modulating T cells, and a shift in the phenotype of macrophages toward a pro-inflammatory profile (30). Levels of TNF-α (8,10), IL-6 (10,11), hs-CRP (9,10), and IL-1β (10) were significantly higher in the relatively smaller FPLD2 subjects than in healthy subjects. Herrero et al. (31) observed elevated systemic inflammation in lipoatrophic aP2-nSREBP-1c transgenic mice, with levels increased 1.9-fold for TNF-α, 10.2-fold for IL-6 and 1.4-fold for MCP-1 as compared to wild-type littermates. In contrast, the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 was 3.3-fold lower in lipodystrophic mice. This inflammation resulted from generalized macrophage infiltration into all AT depots, with substantial numbers of T and B lymphocytes (31). Additional basic research data and clinical data are needed to expand on the few studies that do indeed suggest a pro-inflammatory state in lipodystrophy (8–11). To enable comparison of inflammation to be made with FPLD2 subjects in the future, we are establishing a bio-collection of blood samples from lean, non-mutated control subjects that are matched for sex, age, and BMI. Finally, we plan to assess levels of biomarkers in blood samples to provide an overview of the systemic inflammation in FPLD2.

In whole-body histological examination of lipoatrophic aP2-nSREBP-1c transgenic mice, systemic inflammation was identified by exclusively AT pro-inflammatory cytokine expression with a substantial number of infiltrating macrophages in AT (31). Interestingly, no inflammation was described in other tissues, including the severely steatotic livers. However, Bidault et al. (11) demonstrated that overexpression of p.R482W prelamin-A in transfected human coronary artery endothelial cells was associated with an increase in MCP-1, IL-6, and IL-8 expression in this tissue. Unfortunately, the design of our study did not include direct measures of endothelial dysfunction. The hypothesis that systemic inflammation in FPLD2 originates from sources other than AT inflammation is being debated. Further research in suitable preclinical models is required to determine the degree to which ubiquitous mutated prelamin expression is responsible for inflammation in specific tissues (AT, endothelium). Such work could help to elucidate the genesis of cardio-metabolic outcomes in this population.

The differences in fat mass and body composition between individuals with overweight or obesity could possibly interfere with the degree of inflammation in OB group, and we performed a comparison of the inflammatory biomarker levels between these two subgroups. (Additional file 2). As expected, in regard with previous results, we found higher levels of leptin and hs-CRP in subjects with obesity than subjects with overweight. Furthermore, there was no significant difference in levels for the other biomarkers between the two groups.

FPLD2 and obesity are two insulin resistant diseases in relation with the AT dysfunction. In our study, TG level is significantly higher and HDL-C level is significantly lower in FPLD2 group in comparison with OB group, despite similar HOMA-IR index. Genetic AT dysfunction with severe inappropriately buffers lipid flux and elevated serum FFA and TG, may explain these differences in lipid profile between FPLD2 and OB group. Lastly, TG / HDL-C level parameters influence the level of insulin resistance/sensitivity, they are not the only ones (32). This could explain the difference in TG and HDL-C levels between the two populations in our results.

In conclusion, our study confirms that insulin-resistant patients with FPLD2 and obesity share common complications related to AT dysfunction. Inflammatory biomarker analyses demonstrated that MCP-1 levels and adiponectin levels differ between patients with FPLD2 and patients with obesity. These two AT pathologies thus appear to have different inflammatory profiles. This difference may be related to the impact of the LMNA mutation on both adipose tissue and endothelial cells in FPLD2. Particularities of systemic inflammation in FPLD2 could be linked to the origin of the cytokines and may have an impact on the development of disease complications. These last points remain to be explored.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AT:

-

adipose tissue

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- %BFM:

-

percentage body fat mass

- FFA:

-

Free Fatty Acid

- FPLD2:

-

Familial Partial Lipodystrophy type 2

- HDL-C:

-

high density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HbA1c:

-

hemoglobin A1c

- HOMA-IR:

-

insulin resistance determined by the homeostasis model assessment index

- hs-CRP:

-

high-sensitivity C-reactive protein

- LDL-C:

-

low density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- MUO:

-

metabolically unhealthy obesity

- NAFLD:

-

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- TC:

-

total cholesterol

- TG:

-

triglycerides

- VAT:

-

visceral adipose tissue.

References

Shoelson SE, Lee J, Goldfine AB. Inflammation and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(7):1793–801.

Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, Rahmat A, Abed Y. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci. 2017;13(4):851–63.

Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69:29–35.

Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa KI, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(6):1494–505.

Shackleton S, Lloyd DJ, Jackson SNJ et al. LMNA, encoding lamin A/C, is mutated in partial lipodystrophy. Nature Genetics. 2000;24:153–156.

Varlet AA, Helfer E, Badens C. Molecular and mechanobiological pathways related to the physiopathology of FPLD2. Cells. 2020;9(9):1947.

Sieprath T, Corne TDJ, Nooteboom M, et al. Sustained accumulation of prelamin A and depletion of lamin A/C both cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction but induce different cell fates. Nucleus. 2015;6:236–46.

Wong SP, Huda M, English P, et al. Adipokines and the insulin resistance syndrome in familial partial lipodystrophy caused by a mutation in lamin A/C. Diabetologia. 2005;48(12):2641–9.

Hegele RA, Kraw ME, Ban MR, Miskie BA, Huff MW, Cao H. Elevated serum C-reactive protein and free fatty acids among nondiabetic carriers of missense mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C (LMNA) with partial lipodystrophy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(1):111–6.

Foss-Freitas MC, Ferraz RC, Monteiro LZ, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress activation in adipose tissue induces metabolic syndrome in individuals with familial partial lipodystrophy of the Dunnigan type. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:6.

Bidault G, Garcia M, Vantyghem MC, et al. Lipodystrophy-linked LMNA p.R482W mutation induces clinical early atherosclerosis and in vitro endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013 Sep;33(9):2162–71.

Haque WA, Shimomura I, Matsuzawa Y, Garg A. Serum adiponectin and leptin levels in patients with lipodystrophies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002 May;87(5):2395.

Cao H, Hegele RA. Nuclear lamin A/C R482Q mutation in canadian kindreds with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:109–12.

Kwapich M, Lacroix D, Espiard S, et al. Cardiometabolic assessment of lamin A/C gene mutation carriers: a phenotype–genotype correlation. Diabetes and Metabolism. 2019;45:382–9.

Treiber G, Flaus Furmaniuk A, Guilleux A, et al. A recurrent familial partial lipodystrophy due to a monoallelic or biallelic LMNA founder variant highlights the multifaceted cardiac manifestations of metabolic laminopathies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2021;185(4):453–62.

Le Dour C, Schneebeli S, Bakiri F, et al. A homozygous mutation of prelamin-A preventing its farnesylation and maturation leads to a severe lipodystrophic phenotype: new insights into the pathogenicity of nonfarnesylated prelamin-A. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:856–62.

Robinson K, Prins J, Venkatesh B. Clinical review: Adiponectin biology and its role in inflammation and critical illness. Crit Care. 2011;15:221.

Kawano J, Arora R. The role of adiponectin in obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiometab Syndr. 2009;4(1):44–9.

Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nat Med. 2001;7:941–6.

Zoico E, Garbin U, Olioso D, et al. The effects of adiponectin on interleukin-6 and MCP-1 secretion in lipopolysaccharide-treated 3T3-L1 adipocytes: role of the NF-kB pathway. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24(6):847–51.

Fujita M, Yamamoto H, Yoshida N, Ono R, Matsuoka T, Kihara S. Atheroprotective roles of Adiponectin via CCL2 inhibition. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2021;28(11):1204–13.

Lee YH, Lee SH, Jung ES, et al. Visceral adiposity and the severity of coronary artery disease in middle-aged subjects with normal waist circumference and its relation with lipocalin-2 and MCP-1. Atherosclerosis. 2010;213:592–7.

Treiber G, Guilleux A, Huynh K, Bonfanti O, Flaus-Furmaniuk A, Couret D, Mellet N, Bernard C, Le-Moullec N, Doray B, Jéru I, Maiza JC, Domun B, Cogne M, Meilhac O, Vigouroux C, Meikle PJ, Nobécourt E. Lipoatrophic diabetes in familial partial lipodystrophy type 2: From insulin resistance to diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2022 Nov 15;49(2):101409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2022.101409. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 36400409.

Oral EA, Simha V, Ruiz E, Andewelt A, Premkumar A, Snell P, Wagner AJ, DePaoli AM, Reitman ML, Taylor SI, Gorden P, Garg A. Leptin-replacement therapy for lipodystrophy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(8):570–8.

Bai Y, Sun Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes Rev. 2015;16:127–36.

Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:347–55.

Katherine Esposito A, Pontillo F, Giugliano G, Giugliano R, Marfella G, Nicoletti D, Giugliano. Association of Low Interleukin-10 Levels with the Metabolic Syndrome in Obese Women, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 88, Issue 3, 1 March 2003, Pages 1055–1058.

Tanti JF, Ceppo F, Jager J, Berthou F. Implication of inflammatory signaling pathways in obesity-induced insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2013;3:181. Published 2013 Jan 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2012.00181

Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B, Kahn CR. Critical nodes in signalling pathways: insights into insulin action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006 Feb;7(2):85–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm1837. PMID: 16493415.

Berger S, Ceccarini G, Scabia G, Barone I, Pelosini C, Ferrari F, Magno S, Dattilo A, Chiovato L, Vitti P, Santini F, Maffei M. Lipodystrophy and obesity are associated with decreased number of T cells with regulatory function and pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype. Int J Obes (Lond). 2017 Nov;41(11):1676–84.

Herrero L, Shapiro H, Nayer A, Lee J, Shoelson SE. Inflammation and adipose tissue macrophages in lipodystrophic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Jan 5;107(1):240–5.

Park SY, Gautier JF, Chon S. Assessment of insulin secretion and insulin resistance in human. Diabetes Metab J. 2021 Sep;45(5):641–54.

Acknowledgements

not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by ERDF (European Regional development fund) OMDIABRUN project RE000XXXX (EU—Région Réunion—French State national counterpart), CHU de La Réunion, University of La Réunion and Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.N. and G.T. develop the concept and design the study. G.T. and E.N. did the acquisition of data. G.T. and E.N. interpreted the data. Statistical analysis of the data was performed by A.G., assisted with analysis and interpretation of the data. E.N. and G.T. drafted the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of results and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. E.N. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the final manuscript for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided written informed consents for molecular analyses and the study which has been approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of Sud Mediterranee IV, France, has been performed according to local and European Union ethical rules (N°ID-RCB: 2021-A00105-36).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Treiber, G., Gonthier, MP., Guilleux, A. et al. Familial partial lipodystrophy type 2 and obesity, two adipose tissue pathologies with different inflammatory profiles. Diabetol Metab Syndr 15, 77 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01055-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01055-4