Abstract

Background

Stroke is a serious complication in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM). Arterial stiffness may improve stroke prediction. We investigated the association between carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity [PWV] and the progression of cerebral white matter hyperintensities (WMH), a marker of stroke risk, in patients with T2DM and controls.

Methods

In a 5-year cohort study, data from 45 patients and 59 non-diabetic controls were available for analysis. At baseline, participants had a mean (± SD) age of 59 ± 10 years and patients had a median (range) diabetes duration of 1.8 (0.8–3.2) years. PWV was obtained by tonometry and WMH volume by an automated segmentation algorithm based on cerebral T2-FLAIR and T1 MRI (corrected by intracranial volume, cWMH). High PWV was defined above 8.94 m/s (corresponding to the reference of high PWV above 10 m/s using the standardized path length method).

Results

Patients with T2DM had a higher PWV than controls (8.8 ± 2.2 vs. 7.9 ± 1.4 m/s, p < 0.01). WMH progression were similar in the two groups (p = 0.5). One m/s increase in baseline PWV was associated with a 16% [95% CI 1–32%], p < 0.05) increase in cWMH volume at 5 years follow-up after adjustment for age, sex, diabetes, pulse pressure and smoking. High PWV was associated with cWMH progression in the combined cohort (p < 0.05). We found no interaction between diabetes and PWV on cWMH progression.

Conclusions

PWV is associated with cWMH progression in patients with type 2 diabetes and non-diabetic controls. Our results indicate that arterial stiffness may be involved early in the pathophysiology leading to cerebrovascular diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patients with type 2 diabetes are at high risk of cerebrovascular complications including stroke, vascular dementia and cognitive impairment [1, 2]. The epidemic burden of type 2 diabetes worldwide highlights the need for new biomarkers to improve individual risk prediction and to elucidate mechanisms underlying cerebrovascular disease.

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV), a simple and non-invasive measure of arterial stiffness, is a strong predictor of stroke [3, 4]. Stiffening of the elastic arteries may impair the normal protective impedance mismatch between elastic and muscular arteries permitting excess pulsatile energy to be transmitted into the microcirculation [5]. High-flow low-impedance organs, such as the brain, are particularly vulnerable to these effects, and the pulsatile energy may inflict target organ damage [6]. This notion is supported by cross-sectional studies demonstrating associations between PWV and cerebral white matter hyperintensities (WMH) in various populations [7], including patients with type 2 diabetes [8]. WMHs are established markers of future cerebrovascular disease [9, 10]. It is currently unknown whether PWV is associated with WMH progression and whether this association differs between patients with and without type 2 diabetes.

The aim of this cohort study was to investigate the association between PWV and WMH progression during 5 years follow-up in patients with type 2 diabetes without a history of symptomatic cerebrovascular disease and in healthy sex- and age-matched controls.

Methods

Design and subjects

We performed a 5-year follow-up study comprising 100 patients with type 2 diabetes and 100 age- (± 2 years) and sex-matched controls at the Department of Endocrinology and Internal Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. Other data regarding this population have previously been published [8]. Inclusion criteria at baseline were age > 18 years and, for patients, < 5 years since diagnosis of diabetes. Controls were excluded if diabetes was diagnosed by fasting glucose and oral glucose tolerance tests. Other exclusion criteria were: acute or chronic infectious disease, end-stage renal failure, pregnancy or lactation, prior or current cancer and contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (claustrophobia, magnetic material in the body and a body weight > 120 kg). Participants were invited for a baseline visit (2009–2011) and a 5-year follow-up visit (2014–2016). We obtained blood and urine samples and assessed arterial stiffness, office and ambulatory blood pressure (BP), and anthropometrics at both visits. Moreover, we performed a cerebral MRI at both visits in order to assess WMH burden.

Pulse wave velocity measurements

Examinations were conducted from 8 to 12 a.m. The study subjects had abstained from smoking and intake of food or caffeinated beverages for at least 2 h before examination. Measurements of PWV were performed using an applanation tonometer (SPT-301B; Millar, Houston, TX, USA) and SphygmoCor equipment and software, version 8.0 (AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia). After a minimum of 5 min of rest in the supine position, sequential electrocardiogram-referenced tonometry-based recordings of the pulse wave at the carotid and the femoral artery were performed to determine the PWV. The transit time was determined by the intersecting tangent algorithm method [11], and the path length was calculated by subtracting the distance between the site of the carotid artery pulse measurement and the suprasternal notch from the distance between the site of the femoral artery pulse measurement and the suprasternal notch, all measured directly using a tape measure. The direct path length method was not applied in our primary analysis, as the study was initiated prior to publication of the consensus document on path length measurements. A PWV of 8.94 m/s in our data set corresponds to 10 m/s when converting PWV to the standard path length [4]; a cut-off value that is associated with greater risk of stroke and cardiovascular events [12]. The mean of two PWV measurements per examination was calculated. PWV assessed by the SphygmoCor device is characterized by good reproducibility in patients with type 2 diabetes and healthy individuals [13].

Magnetic resonance imaging

At baseline, a cerebral MRI was performed with an eight-channel SENSE head coil on a 1.5 T MRI scanner (Achieva, Philips, Best, Netherlands) to obtain both axial T2-FLAIR scans (256 × 256 × 22 with acquisition matrix of 256 × 191; slice thickness 5 mm; TE = 130 ms; TR = 6000 ms; TI = 2200 ms; flip angle 90º) and T1-weighted 3D FFE scans (256 × 256 × 150 with acquisition matrix of 256 × 256; slice thickness 2 mm; TE = 4.60 ms; TR = 25 ms; flip angle 30º).

At follow-up, cerebral MRI was performed using a 32-channel head coil on a 3 T scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra system, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) to obtain both a T2-FLAIR sequence (320 × 310 × 45 with acquisition matrix of 320 × 217; slice thickness 3 mm; TE = 117 ms; TR = 9000 ms; TI = 2500 ms; flip angle 150º), and T1-weighted uniform MP2RAGE sequence (256 × 240 × 176 with acquisition matrix of 256 × 240; slice thickness 1 mm; TE = 2.98 ms; TR = 5000 ms; flip angle 0º).

After manual inspection of image quality, the obtained sequences were processed with an × 86-based workstation. The T1W-images from follow-up (MP2RAGE) were prepared for analysis with removal of background noise using the robust T1W method. We used the same β-value for all image sequences which yielded an adequate noise suppression without introduction of significant intensity bias [14].

The volume and number of WMH at baseline and follow-up was quantified by an automated segmentation of both T1 and T2-FLAIR sequences using the Lesion Growth Algorithm (LGA) [15] as implemented in the LST toolbox 1.2.3 (www.statistical-modelling.de/lst.html) working in Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) version 8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8/) as described elsewhere[16]. In the analysis we used an initial threshold (κ = 0.3) which was confirmed by visual inspection. As patients were evaluated with different scanners at baseline and follow-up, we conducted secondary analysis with the LGA (T1 and T2FLAIR images, κ = 0.3) and the Lesion Prediction Algorithm (LPA) (T2 FLAIR images only) [17] using SPM12 and LST toolbox 3.0.0 in order to validate the primary analysis (LGA SPM8 has shown better correlation with visual volume assessment[16] and were thus used in our primary analysis). WMH volumes were divided by intracranial volume in order to correct for individual differences in head size (cWMH). Furthermore, we included another secondary analysis of white matter hypointensity volumes using volumetric segmentation of the recorded T1-weighted images (Freesurfer 5.3, https://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu) [18]. Longitudinal analysis was performed according to Reuter et al. [19].

Cerebral infarctions were defined as areas with volume loss surrounded by signals consistent with gliosis and were classified as lacunar when their size was less than 15 mm.

Other measurements

Ambulatory BP was measured at 20-min intervals for 24 h using Spacelab 90,217 (Spacelabs Healthcare, Issaquah, WA, USA). Office BP was measured on the right arm with an appropriately sized cuff, and mean systolic and diastolic BPs were calculated as the average of three measurements obtained after a minimum of 5 min of rest in seated position (Riester Champion N, Riester GmbH, Jungingen, Germany). Urinary albumin excretion was evaluated by albumin-to-creatinine ratios in three morning urine samples. Finally, the participants’ medical histories were obtained by questionnaire.

Statistics

Variables with a normal distribution are presented as either mean ± SD (participant characteristics) or mean and 95% CI (analysis of association), and skewed data are presented as median (interquartile range). Dichotomous data are presented as n (%).

The distributions of continuous variables were tested with histograms and QQ-plots.

If normally distributed, means of two groups were compared with Student’s paired t test for matched data or with Student’s unpaired t test for independent data. Skewed data were log-transformed before using a t test. If normal distribution was not achieved by log transformation, the Wilcoxon signed rank test or the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test was applied as appropriate. Dichotomous variables were compared with McNemar’s test or the Chi2 test as appropriate.

We used linear and logistic regression to evaluate the association between PWV at baseline and cWMH progression. Robust standard errors were calculated to account for clustering in repeated measurements. The following covariates were considered for inclusion in multivariate logistic regression models: age, sex, diabetes (yes/no), office pulse pressure (PP)[20] and smoking (no smoking vs. current/former smoking). Additionally, we exchanged PWV as a continuous variable with PWV dichotomized < / > 8.94 m/s (corresponding to the clinical cut-off of 10 m/s when using the standard path length). There were small differences in follow-up time between patients with type 2 diabetes and controls, and therefore we repeated the analysis with cWMH volume progression corrected for follow-up time. Furthermore, as lacunar infarcts may have been included in the automatic cWMH segmentation, we repeated the analyses without patients with presence of infarcts. Finally, we tested the interaction between diabetes status and PWV on the effect on cWMH progression.

Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata software version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Participant characteristics

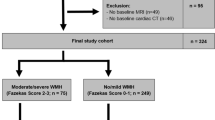

A total of 63 patients with type 2 diabetes and 72 controls attended the follow-up visit. Data from participants with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack at baseline (n = 4), participants with missing PWV (n = 10) or missing MRI (n = 17) were excluded from the analysis (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Data from 45 patients and 59 controls were available for our final analysis (Baseline characteristics of participants attending versus those not attending the follow-up visit are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1).

Patients with type 2 diabetes had, compared with controls, a higher BMI, heart rate and PWV, but more favourable plasma lipids, and BP profiles at baseline (Table 1). The good risk factor control observed in the diabetes group could probably be ascribed to the fact that a high proportion of the patients with diabetes received antihypertensive drugs and statins.

White matter hyperintensity progression

Patients with type 2 diabetes had comparable WMH volumes compared to controls both at baseline and follow-up. In accordance, progression in WMH volumes was similar in the two groups during the study period (Table 2) and the median volume increase in WMH was 984mm3 for the combined cohort. Similarly, the number of WMHs was low at baseline but increased similarly in both groups. Using cWMH did not change the results (p < 0.44). At baseline, three (7%) patients and three (8%) controls had signs of subclinical cerebral infarctions on MRI (p = 1.0), which did not change at follow-up. No participants had signs of brain tumors.

PWV and cWMH progression

Baseline PWV was associated with increased cWMH volume progression in both crude and adjusted linear regression analysis in the combined cohort (Fig. 1; Table 3). In adjusted separate group analysis, this association was attenuated.

PWV > 8.94 m/s (corresponding to a high PWV above 10 m/s using the standard path length measurement), was associated with high cWMH volume progression in the combined cohort and in the diabetes and control groups separately (Fig. 2). The association remained significant in the combined cohort in multivariate analysis (Table 3). The results were similar in analysis with cWMH volume progression corrected for follow-up time and in analysis exchanging PP with mean arterial pressure (data not shown). Furthermore, the results were not attenuated when we added antidiabetic, anthihypertensive and/or lipid-lowering drug use (both separately or all three variables together) nor when we added hba1c to the multivariate regression model of the combined cohort. Finally, we rerun the analysis without the participants with presence of lacunar infarcts, with similar results in crude/adjusted analysis of continuous PWV (p < 0.05), however attenuated in adjusted analysis with dichotomized PWV (p = 0.08). Diabetes did not modify the association between PWV and cWMH volume progression (interaction term − 11%, 95%CI − 32 to 18%, p = 0.44).

In secondary analyses, we used the LST toolbox 3.0.0 and SPM12 to perform lesion segmentation of both T2 FLAIR images only (LPA12) and of a combination of T1 and T2 FLAIR (LGA12). White matter hypointensity volumes were also estimated using Freesurfer 5.3 based volumetric segmentation of T1-weighted images (as a proxy for T2 FLAIR WMH). We found results with similar direction of association although the associations were attenuated in the analysis of WMH segmentation based on T1-weighted images (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate PWV and cWMH volume progression in a cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes with no clinical history of cerebrovascular disease and age- and sex-matched controls. We found that PWV was associated with higher cWMH volume progression in the combined cohort, independent of known risk factors such as age, sex, blood pressure, and smoking status.

Cerebral WMHs are established surrogate markers of cerebrovascular disease like stroke, dementia and cognitive decline [9, 10]. Cerebral small-vessel damage is considered the causative factor in WMH development [21,22,23], and major determinants of WMH include age, hypertension, smoking, and diabetes [24,25,26]. We found no difference in WMH burden or progression between patients with type 2 diabetes and controls at either baseline [8] or follow-up. However, the potential differences between the two groups may be ameliorated by the good glycaemic, lipid and BP control observed in the patient group. Additionally, as patients were enrolled shortly after their diagnosis of diabetes, it may be speculated that WMH progression would start to progress faster at later stages of the disease (i.e., after the 5-year follow-up visit). This is supported by the findings of Debette et al. [27] showing no association between midlife diabetes and WMH progression. In contrast, the study results of King et al. [28] showed WMH progression at a faster pace in patients with type 2 diabetes compared to healthy individuals after the age of 50 years, but not before (the mean age at inclusion in our study was 58.5 years). Yet another explanation may be that diabetes status modifies the effect of WMH on stroke risk, e.g., the presence of WMH in diabetes patients may confer a higher risk of stroke compared to similar WMH presence in non-diabetic individuals. Prospective studies are needed to further investigate these questions.

Arterial stiffness may be a key factor in the pathogenesis of WMH. PWV has been linked to WMH in several cross-sectional studies [7], and we have previously reported a cross-sectional association between PWV and WMH in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes [8]. In contrast, Nomura and colleagues found no independent association between brachial-ankle PWV and the presence of silent infarctions in older Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes [29]. Two studies have observed longitudinal associations between baseline PWV and WMH [30, 31]. Rosano et al. [30] found baseline PWV to be associated with WMH 10 years later in a population study of elderly subjects (12% with diabetes). Tsao et al. [31] did not find an association between baseline PWV and WMH progression in a population-based cohort in which 9% were patients with diabetes. However, no previous studies prospectively investigated the association between PWV and progression of WMH in a diabetes population.

Interestingly, we found an association between PWV and cWMH progression in the combined cohort and our test for interaction did not suggest diabetes to modify the association between PWV and WMH progression. The discrepancy between our results and that of Tsao, might be due to different methodologies. Alternatively, the higher proportion of diabetes patients in our study may change the distribution of PWV towards higher values. In line with this speculation, it has been suggested that PWV only becomes a risk factor when it exceeds a certain threshold [32], e.g., 10 m/s which is the suggested cut-off value for high arterial stiffness [4]. Another important question is, whether high PWV affects the brain globally or preferentially in specific regions of the brain. In the latter case, the global assessment of WMH burden may have attenuated the observed associations between PWV and WMH progression. In general, stiffness of the elastic arteries impairs the normal impedance mismatch between elastic and muscular arteries, leading to a transfer of high pulsatile energy to the microcirculation [5]. This pulsatile barotrauma as well as the compensatory remodelling of the arteries that leads to a reduced vasodilatatory reserve, may affect the brain globally [5]. However, it has also been suggested that increased pulse wave velocity and pressure pulsatility may lead to pressure changes of the cerebrovascular fluid. In turn this may affect the periventricular parenchyma and cause periventricular WMLs [33]. Future studies evaluating WMH progression in specific brain regions may help answer these questions.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, a 1.5 T MR scanner was used at baseline and a 3.0 T MR scanner at follow-up. This may cause a higher volume estimation at follow-up, partly because of better detection of punctate lesions [34, 35]. Theoretically, our results may therefore reflect the cross-sectional association between PWV and WMH as reported previously [8]. However, in both LGA8 analysis and sensitivity analysis using different segmentation techniques (see “Methods”), we have visually observed that WMH progression vary considerably at similar baseline WMH volumes which suggests that our results reflect actual WMH progression. Furthermore, all of the analyses showed the same direction of association as the main analysis based on LGA8. Finally, the scanner changed in all patients at follow-up, independent of PWV value, and therefore it might not affect the association of PWV with cWMH. Secondly, due to the modest sample size, analysis was at risk of type 2 error, and multivariable regression analysis was restricted to only few confounding covariates. Thirdly, the dropout of 37 patients and 28 controls before the follow-up visit might affect the external validity of the study. However, importantly, the baseline characteristics between participants who participated in the follow-up visit were not different from the participants who did not attend (Additional file 1: Table S1). Thus, the findings of this study may be applicable to other patients newly diagnosed with diabetes and individuals without diabetes.

Conclusions

Arterial stiffness is associated with cWMH progression in patients with type 2 diabetes and matched controls. Arterial stiffness may candidate as a new risk marker for future cerebrovascular events and could potentially be an important target for intervention.

Availability of data and materials

The data of this study is available on request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- LGA:

-

Lesion growth algorithm

- LPA:

-

Lesion prediction algorithm

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PWV:

-

Pulse wave velocity

- WMH:

-

White matter hyperintensities

References

Bejot Y, Giroud M. Stroke in diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36(Suppl 3):S84-87.

Moran C, Phan TG, Chen J, Blizzard L, Beare R, Venn A, Munch G, Wood AG, Forbes J, Greenaway TM, et al. Brain atrophy in type 2 diabetes: regional distribution and influence on cognition. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(12):4036–42.

Laurent S, Katsahian S, Fassot C, Tropeano AI, Gautier I, Laloux B, Boutouyrie P. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34(5):1203–6.

Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace-Raso FU, Protogerou AD, et al. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30(3):445–8.

Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105(5):1652–60.

Saji N, Toba K, Sakurai T. Cerebral small vessel disease and arterial stiffness: tsunami effect in the brain? Pulse. 2016;3(3–4):182–9.

van Sloten TT, Protogerou AD, Henry RM, Schram MT, Launer LJ, Stehouwer CD. Association between arterial stiffness, cerebral small vessel disease and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;53:121–30.

Laugesen E, Hoyem P, Stausbol-Gron B, Mikkelsen A, Thrysoe S, Erlandsen M, Christiansen JS, Knudsen ST, Hansen KW, Kim WY, et al. Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity is associated with cerebral white matter lesions in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(3):722–8.

Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3666.

Wardlaw JM, Smith C, Dichgans M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(7):684–96.

Chiu YC, Arand PW, Shroff SG, Feldman T, Carroll JD. Determination of pulse wave velocities with computerized algorithms. Am Heart J. 1991;121(5):1460–70.

Ben-Shlomo Y, Spears M, Boustred C, May M, Anderson SG, Benjamin EJ, Boutouyrie P, Cameron J, Chen CH, Cruickshank JK, et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity improves cardiovascular event prediction: an individual participant meta-analysis of prospective observational data from 17,635 subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(7):636–46.

Laugesen E, Rossen NB, Hoyem P, Christiansen JS, Knudsen ST, Hansen KW, Hansen TK, Poulsen PL. Reproducibility of pulse wave analysis and pulse wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2013;73(5):428–35.

O’Brien KR, Kober T, Hagmann P, Maeder P, Marques J, Lazeyras F, Krueger G, Roche A. Robust T1-weighted structural brain imaging and morphometry at 7T using MP2RAGE. PloS ONE. 2014;9(6):e99676.

Schmidt P, Gaser C, Arsic M, Buck D, Forschler A, Berthele A, Hoshi M, Ilg R, Schmid VJ, Zimmer C, et al. An automated tool for detection of FLAIR-hyperintense white-matter lesions in multiple sclerosis. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3774–83.

Egger C, Opfer R, Wang C, Kepp T, Sormani MP, Spies L, Barnett M, Schippling S. MRI FLAIR lesion segmentation in multiple sclerosis: does automated segmentation hold up with manual annotation? Neuroimage Clin. 2017;13:264–70.

Schmidt P. Bayesian inference for structured additive regression models for large-scale problems with applications to medical imaging. Ludwig Maximilians-Universität München 2017.

Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I Segm Surf Reconstr Neuroimage. 1999;9(2):179–94.

Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):1402–18.

Kim EJ, Park CG, Park JS, Suh SY, Choi CU, Kim JW, Kim SH, Lim HE, Rha SW, Seo HS, et al. Relationship between blood pressure parameters and pulse wave velocity in normotensive and hypertensive subjects: invasive study. J Hum Hypertens. 2007;21(2):141–8.

O’Sullivan M, Lythgoe DJ, Pereira AC, Summers PE, Jarosz JM, Williams SC, Markus HS. Patterns of cerebral blood flow reduction in patients with ischemic leukoaraiosis. Neurology. 2002;59(3):321–6.

Topakian R, Barrick TR, Howe FA, Markus HS. Blood-brain barrier permeability is increased in normal-appearing white matter in patients with lacunar stroke and leucoaraiosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81(2):192–7.

Wardlaw JM, Valdes Hernandez MC, Munoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(6):001140.

Jeerakathil T, Wolf PA, Beiser A, Massaro J, Seshadri S, D’Agostino RB, DeCarli C. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: the Framingham study. Stroke. 2004;35(8):1857–61.

Dufouil C, de Kersaint-Gilly A, Besancon V, Levy C, Auffray E, Brunnereau L, Alperovitch A, Tzourio C. Longitudinal study of blood pressure and white matter hyperintensities: the EVA MRI Cohort. Neurology. 2001;56(7):921–6.

Gouw AA, van der Flier WM, Fazekas F, van Straaten EC, Pantoni L, Poggesi A, Inzitari D, Erkinjuntti T, Wahlund LO, Waldemar G, et al. Progression of white matter hyperintensities and incidence of new lacunes over a 3-year period: the leukoaraiosis and disability study. Stroke. 2008;39(5):1414–20.

Debette S, Seshadri S, Beiser A, Au R, Himali JJ, Palumbo C, Wolf PA, DeCarli C. Midlife vascular risk factor exposure accelerates structural brain aging and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2011;77(5):461–8.

King KS, Peshock RM, Rossetti HC, McColl RW, Ayers CR, Hulsey KM, Das SR. Effect of normal aging versus hypertension, abnormal body mass index, and diabetes mellitus on white matter hyperintensity volume. Stroke. 2014;45(1):255–7.

Nomura K, Hamamoto Y, Takahara S, Kikuchi O, Honjo S, Ikeda H, Wada Y, Nabe K, Okumra R, Koshiyama H. Relationship between carotid intima-media thickness and silent cerebral infarction in Japanese subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(1):168–70.

Rosano C, Watson N, Chang Y, Newman AB, Aizenstein HJ, Du Y, Venkatraman V, Harris TB, Barinas-Mitchell E, Sutton-Tyrrell K. Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts focal white matter hyperintensities in a biracial cohort of older adults. Hypertension. 2013;61(1):160–5.

Tsao CW, Himali JJ, Beiser AS, Larson MG, DeCarli C, Vasan RS, Mitchell GF, Seshadri S. Association of arterial stiffness with progression of subclinical brain and cognitive disease. Neurology. 2016;86(7):619–26.

Nilsson ED, Elmstahl S, Minthon L, Nilsson PM, Pihlsgard M, Tufvesson E, Nagga K. Nonlinear association between pulse wave velocity and cognitive function: a population-based study. J Hypertens. 2014;32(11):2152–7.

Bateman GA, Levi CR, Schofield P, Wang Y, Lovett EC. The venous manifestations of pulse wave encephalopathy: windkessel dysfunction in normal aging and senile dementia. Neuroradiology. 2008;50(6):491–7.

Bachmann R, Reilmann R, Schwindt W, Kugel H, Heindel W, Kramer S. FLAIR imaging for multiple sclerosis: a comparative MR study at 1.5 and 3.0 Tesla. Eur Radiol. 2006;16(4):915–21.

Stankiewicz JM, Glanz BI, Healy BC, Arora A, Neema M, Benedict RH, Guss ZD, Tauhid S, Buckle GJ, Houtchens MK, et al. Brain MRI lesion load at 1.5T and 3T versus clinical status in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging. 2011;21(2):e50-6.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank laboratory technicians Merete Møller, Lone Kvist, Eva Schriver and Lisa Buus, from the Medical Research Laboratory at the Department for Endocrinology and Internal Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital, and radiologic technologist Michael Geneser, Center of Functionally Integrative Neuroscience, Aarhus University Hospital, for excellent technical assistance. Thorbjørn Søndergaard Engedal, MD, provided assistance with the MRI scans.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants from Aarhus University, Karen Anthonius Mindelegat, Søster and Verner Lipperts Foundation, the Danish Diabetes Academy, the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Health Research Fund of Central Denmark Region. The study funders were not involved in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; and did not impose any restrictions regarding the publication of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KLF, EL, TKH and PLP generated the study hypothesis and developed the study design. KLF acquired, analyzed, and interpreted data; and drafted and revised the manuscript. EL, TKH, PH, CSB and PLP analyzed and interpreted data, handled supervision, provided administrative support, obtained funding and critically revised the manuscript. BS, WYK, LØ and DZ analyzed and interpreted data, provided technical support, and critically revised the manuscript. KLF is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors approved the submission of this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Central Denmark Region (1-10-72-349-13) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (1-16-02-505-13), Denmark. All patients gave their written, informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Participant flow. Table S1. Baseline characteristics in participants attending versus not attending the follow-up visit. Table S2. Pulse wave velocity and white matter hyperintensity progression.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Funck, K.L., Laugesen, E., Høyem, P. et al. Arterial stiffness and progression of cerebral white matter hyperintensities in patients with type 2 diabetes and matched controls: a 5-year cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr 13, 71 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00691-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00691-y