Abstract

Background

Southeast Asia is regarded as a hotspot for the diversity of ixodid ticks. In this geographical region, Vietnam extends through both temperate and tropical climate zones and therefore has a broad range of tick habitats. However, molecular-phylogenetic studies on ixodid tick species have not been reported from this country.

Methods

In this study, 1788 ixodid ticks were collected from cattle, buffalos and a dog at 10 locations in three provinces of northern Vietnam. Tick species were identified morphologically, and representative specimens were molecularly analyzed based on the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) and 16S rRNA genes. Fifty-nine tick species that are indigenous in Vietnam were also reviewed in the context of their typical hosts in the region.

Results

Most ticks removed from cattle and buffalos were identified as Rhipicephalus microplus, including all developmental stages. Larvae and nymphs were found between January and July but adults until December. Further species identified from cattle were Rhipicephalus linnaei, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides, Amblyomma integrum and Haemaphysalis cornigera. Interestingly, the latter three species were represented only by adults, collected in one province: Son La. The dog was infested with nymphs and adults of R. linnaei in July. Phylogenetically, R. microplus from Vietnam belonged to clade A of this species, and R. haemaphysaloides clustered separately from ticks identified under this name in China, Taiwan and Pakistan. Amblyomma integrum from Vietnam belonged to the phylogenetic group of haplotypes of an Amblyomma sp. reported from Myanmar. The separate clustering of H. cornigera from Haemaphysalis shimoga received moderate support.

Conclusions

Three tick species (R. linnaei, A. integrum and H. cornigera) are reported here for the first time in Vietnam, thus increasing the number of indigenous tick species to 62. Clade A of R. microplus and at least R. linnaei from the group of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato occur in the country. There is multiple phylogenetic evidence that different species might exist among the ticks that are reported under the name R. haemaphysaloides in South and East Asia. This is the first report of A. integrum in Southeastern Asia.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Hard ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) have long been known for their high veterinary-medical importance, especially owing to the transmission of tick-borne pathogens which account for significant losses in terms of human and animal health and life. The global economic importance of ticks is particularly high for livestock, and tick-borne diseases especially affect regions with tropical climate [1]. Southeastern Asian countries (Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Laos and Vietnam) belong to the Oriental Zoogeographic Region, characterized by having mainly tropical climate and consequently very rich species diversity [2]. For instance, compared to its land surface area, the Oriental Region probably has the highest number of insect species [3], and in Southeast Asia nearly twice as many spider species occur than in South Asia [4].

Knowledge on the tick fauna of continental Southeast Asia has intensified during the past decades [5]. This does not necessarily imply that the number of reported species will increase in time, because clarification of their taxonomic status may entail fewer well-established and recognized species in contrast to their ever-reported number (which may include taxonomically synonymous or questionable records). This is well exemplified by the fact that during the past 3 decades initially 96 hard tick species [6], then 100 [7] and finally 93 ixodid tick species were shown to be indigenous to Southeast Asia [5].

In some of the countries of this region, the number of tick species considered indigenous remained relatively constant until recently ([2, 5]: in Cambodia 17–18, in Malaysia 42–43, in Myanmar 34, in Thailand 58), with the exception of Laos where this number increased from 26 [5] to 30 [2]. Taken together, Southeast Asia should be regarded as a hotspot for the diversity of ixodid tick species, because this region represents only approximately 1.5% of the whole continental land surface but provides suitable habitats for the occurrence of at least 12.1% of all known tick species [2, 5, 6].

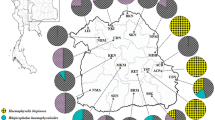

Importantly, in the whole of Southeast Asia, Vietnam was reported to have the highest number of ixodid tick species, i.e. 59 [5, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48] (Table 1). However, more recently only 57 were considered as unambiguously native to this country [2]. Vietnam has significant north-to-south expansion, overbridging the temperate and tropical climate zones. This bears impact on its faunal richness and species diversity, as illustrated by the highest number of Haemaphysalis species in a single geographical region [5]. Moreover, knowledge on the ixodid fauna of Vietnam bears high relevance to the potential transportation of a broad spectrum of tick species by birds in the direction of China and Japan to the north, as well as to Indonesia and even Australia in the south [49].

However, in Vietnam the latest large-scale tick surveys were conducted decades ago [14, 16, 18]. In addition, prior to the era of molecular methods, data of these studies were all based on morphological identification of tick species. As recently reported, the lack of reference sequences and standard taxonomic keys specific to native tick species makes morphological identification of Vietnamese ticks difficult [25]. Based on National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Nucleotide database, among Ixodes species only bat-associated ones were barcoded from Vietnam [12, 50]. Although several new Dermacentor species were described from specimens collected in this country [e.g. 28, 34], corresponding genetic data are not accessible. Considering other ixodid genera, only a single sequence of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato is available from Vietnam in GenBank [51].

In light of the above, the aims of this study were: (i) to collect large numbers of ticks from cattle and buffalo in northern Vietnam, (ii) to identify all specimens morphologically and (iii) to select representatives of each species for molecular-phylogenetic analyses based on two mitochondrial markers. In addition, it was also highly relevant in this context (iv) to review and update the list of all ixodid species already known or discovered here to occur in Vietnam. At the same time, this study is also meant as an initiative for barcoding all tick species of Vietnam.

Methods

Sample collection and morphological identification of tick species

Hard ticks were collected from 60 cattle, five buffalos and a dog between July 2022 and April 2023 at 10 locations in three provinces of Northern Vietnam (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1). None of the animals included in this study were imported from abroad. Depending on sampling conditions (e.g. restraint of animals and accessibility to affected skin surfaces), the great majority or all ticks were removed, allowing the estimation of mean infestation intensity: number of conspecific ticks divided by the number of hosts. All ticks were stored in 96% ethanol. Tick species were morphologically identified according to standard keys and illustrations [52,53,54,55,56,57]. Ticks were examined and pictures were made with a VHX-5000 digital microscope (Keyence Co., Osaka, Japan).

DNA extraction and PCR analyses

Ticks were disinfected on their surface with sequential washing in 10% sodium-hypochlorite, tap water and distilled water. DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), including an overnight digestion in tissue lysis buffer and Proteinase K at 56 °C. An extraction control (tissue lysis buffer) was also processed with the tick samples to monitor cross-contamination.

PCR amplification of an approximately 710-bp-long part of the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene was performed with the primers LCO1490 (forward: 5ʹ-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3ʹ) and HCO2198 (reverse: 5ʹ-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3ʹ), which are most widely used for barcoding ticks [58, 59]. The reaction mixture, in a volume of 25 µl, contained 1 U (0.2 µl) HotStarTaq Plus DNA polymerase, 2.5 µl 10 × CoralLoad Reaction buffer (including 15 mM MgCl2), 0.5 µl PCR nucleotide Mix (0.2 mM each), 0.5 µl (1 µM final concentration) of each primer, 15.8 µl ddH2O and 5 µl template DNA. The PCR was performed with the following conditions: an initial denaturation step at 95 ℃ for 5 min was followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94 ℃ for 40 s, annealing at 48 ℃ for 1 min and extension at 72 ℃ for 1 min. Final extension was performed at 72 ℃ for 10 min.

Another PCR was used to amplify an approximately 460-bp-fragment of the 16S rDNA gene of Ixodidae [60], with the primers 16S + 1 (5ʹ-CTG CTC AAT GAT TTT TTA AAT TGC TGT GG-3ʹ) and 16S-1 (5ʹ-CCG GTC TGA ACT CAG ATC AAG T-3ʹ). In the latter reaction, components and cycling conditions were the same as above, except for annealing at 51 °C.

Phylogenetic analyses

In all PCRs, non-template reaction mixture served as negative control. Extraction controls and negative controls remained PCR negative in all tests. Purification and sequencing of the PCR products were done by Eurofins Biomi Ltd. (Gödöllő, Hungary). Quality control and trimming of sequences were performed with the BioEdit program. Obtained sequences were compared to GenBank data by the nucleotide BLASTN program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). New sequences were submitted to GenBank under the following accession numbers (cytochrome c oxidase subunit I [cox1] gene: PP197235-PP197241, 16S rRNA gene: PP197249-PP197254). Sequences from other studies (retrieved from GenBank) included in the phylogenetic analyses had 99–100% coverage with sequences from this study. Sequence datasets were resampled 1000 times to generate bootstrap values. Phylogenetic analyses of cox1 and 16S rRNA sequences were performed with the Maximum Likelihood method, General Time Reversable (GTR) or Tamura-Nei models, respectively, according to the selection of the MEGA software [61, 62].

Results

Morphological identification, host-associations and spatiotemporal distribution of tick species

Altogether, 1788 ixodid ticks were collected. These belonged to five species (Table 2). Most (n = 1710) of ticks removed from cattle and buffalos were identified as Rhipicephalus microplus, including larvae (n = 10), nymphs (n = 341) and adults (n = 1359). Larvae and nymphs were found between January and July, while males and females were found until December. The estimated intensity of infestation ranged from a few ticks (December to April) up to 128 or 153 ticks per cattle in March and July, respectively (Table 2).

Four additional species identified among ticks from cattle were Rhipicephalus linnaei (n = 2; Fig. 1A, C), Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides (n = 2; Fig. 1B, D), Amblyomma integrum (n = 1) (Fig. 2A–D) and Haemaphysalis cornigera (n = 2) (Fig. 3A–C). Interestingly, the latter three species were only represented by females, collected in one province: Son La (Table 2). The single dog sampled in this study was infested by nymphs and adults of R. linnaei (n = 71) in July (Table 2).

Morphological characters of Rhipicephalus linnaei (A, C) and R. haemaphysaloides (B, D) females collected in Vietnam. A, B Scutum and dorsal view of palps: (1) bending of cervical grooves A much anteriorly to or B near the level of eyes (white dashed line); (2) punctuations of caudo-central area of scutum A dense or B scarce. C, D Ventral view of basis capituli and coxae: (1) posteroventral palpal spur has C perpendicular or D acute angle; (2) medial edge of coxa I encloses C acute angle or D is parallel with the incision of coxa I; (3) genital groove anteriorly C flattened or D rounded.

Morphological characters of Amblyomma integrum female collected in Vietnam. (A) Scutum and dorsal view of palps: (1) punctuations deep and large laterally, along the median line interspersed with shallow and small ones; (2) medial edge of scapular region slightly convex; (3) posterior margin narrow, rounded; (4) palpal segment III has small lateral and medial protuberance; (B) ventral view of basis capituli and coxae I: (5) the external spur of coxa I is much longer than the internal spur; (6) spur-like callosity anteriorly on coxa I; (C) ventral view of palpal basis and hypostome: (7) palpal segment I with a longitudinal, sharp ridge ending with a small, rounded spur; (8) dental formula 3/3; (D) spiracular plate: (9) opening surrounded by an elongate deepening approximately 2/3 of the length of plate; (10) medial and lateral margins enclose an acute angle; (11) dorsal prolongation short, narrow

Morphological characters of Haemaphysalis cornigera female collected in Vietnam. (A) Dorsal view of basis capituli and palps: (1) posterior margin of palpal segment II wavy, with a prominent medial spur-like protrusion; (2) posterior margin of palpal segment III with sharp, triangular spur; (3) cornuae conspicuous, caudally directed, pointed; (B) ventral view of basis capituli and palps: (4) there are five infrainternal setae; (5) between the long, triangular spurs on palpal segments III the hypostome has a dental formula of 4/4; (C) spiracular plate subcircular or subquadrate, (6) dorsally with straight edge and hardly visible, blunt dorsal prolongation; (7) opening subcentral, surrounded with an oval area void of aeropyles

Molecular-phylogenetic analyses of tick species

Among the four specimens of R. microplus that were molecularly analyzed, two cox1 haplotypes were identified. One of these (PP197236) had 100% (633/633 bp) identity in its cox1 sequence with several GenBank entries, among the others from the southernmost province of China (Hainan: OQ704525), Kenya (MT430985), South Africa (KY457541) and Colombia (MF363057). An isolate from Cambodia had lower (99.3%; 632/636 bp) sequence identity than this R. microplus isolate from Vietnam. Similarly, the 16S rRNA sequence of R. microplus from Vietnam (PP197250) was 99.8% (410/411 bp) identical to haplotypes reported from Thailand (KC170742), China (Hainan: OQ725491) and Taiwan (AY974232) but only 99.3% (407/410 bp) homologous to an isolate from Cambodia (KC503260). The Vietnamese haplotypes belonged to clade A of R. microplus as a sister group to Rhipicephalus australis (Figs. 4, 5).

Phylogenetic tree of Metastriata based on the cox1 gene. Genera and species were selected based on geographical and taxonomical relevance to this study. In each row of individual sequences, the country of origin and the GenBank accession number are shown after the species name. Sequences from this study are indicated with red fonts and bold maroon accession numbers. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and the General Time Reversible model. Sequence dataset was resampled 1000 times to generate bootstrap values. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 50 nucleotide sequences, and there were a total of 633 positions in the final dataset

Phylogenetic tree of Metastriata based on the 16S rRNA gene. Genera and species were selected based on geographical and taxonomical relevance to this study. In each row of individual sequences, the country of origin and the GenBank accession number are shown after the species name. Sequences from this study are indicated with red fonts and bold maroon accession numbers. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and the Tamura-Nei model. Sequence dataset was resampled 1000 times to generate bootstrap values. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 60 nucleotide sequences, and there were a total of 454 positions in the final dataset

The cox1 sequence of R. linnaei from Vietnam (PP197240) showed 100% identity to sequences of conspecific ticks from Laos (MW429383) and Australia (MW429381) and was also nearly identical (99.7%: 637/639 bp) to another from China (JX416325). The predominant 16 rRNA haplotype of R. linnaei from Vietnam (i.e. relevant to four out of five examined ticks) (PP197252) had (421/423 bp) identity to the corresponding sequence of ticks from Laos (MW429383) and China (JX416325). Both the cox1 and 16S rRNA sequences of R. linnaei from Vietnam clustered as a sister group to haplotypes including Rhipicephalus rutilus (Figs. 4, 5).

The two cox1 haplotypes of R. haemaphysaloides from Vietnam differed only in a single nucleotide: one of them (PP197238) was 99.7% (638/640 bp) identical to conspecific haplotypes available in GenBank from southern (Hunan: KM083593) and southcentral (Sichuan: JQ737085) provinces of China. Interestingly, R. haemaphysaloides from Vietnam was phylogenetically well separated from specimens reported under this species name from Southern China (Dehong: OM977038) and Pakistan (MT800315) (Fig. 4). Both representatives of this species identified in Vietnam had identical 16S rRNA haplotypes (PP197251) and had the closest sequence homology (99.8%; 420/421 bp) to R. haemaphysaloides from China (Yunnan: KU664522) and Thailand (KC170743) but only 94.3% (397/421 bp) to another haplotype from Taiwan (AY972534). These relationships were well reflected by the 16S rRNA phylogenetic analysis, indicating divergence within R. haemaphysaloides with high (84–85%) support (Figs. 4, 5). In addition, the sequence length coverage was lower (96%) and the identity 94.6% (383/405 bp) to a haplotype reported from Pakistan (MT799956).

The cox1 sequence of A. integrum (PP197235) had 99.1% (574/579 or 560/565 bp) sequence identity to those of conspecific ticks reported from India (OP473983, OQ318206, OQ306569), which were omitted from the phylogenetic analysis because of the low sequence length coverage. The identity was 99.7–99.8% (635–636/637 bp) to further specimens from Myanmar (LC633550, LC633553) not identified to the species level. On the other hand, A. integrum collected in Vietnam had only 98.3% (626/637 bp) cox1 sequence identity to Amblyomma geoemydae from Malaysia (isolate SGL03d: OL629478). The phylogenetic clustering (sister position) of A. integrum (Vietnam) and A. geoemydae (Malaysia) was well supported (Fig. 4), but their p-distance was low, 1.7% (11/637 bp). The 16S rRNA haplotype of A. integrum identified in Vietnam (PP197249) showed 99.5–99.8% (413/415 or 410/411 bp) sequence homology to isolates reported from Thailand (KC170737, MZ490781), a similar 99.5% (412/414 bp) to ticks morphologically not identified to the species level from Myanmar (e.g. LC633553) but only 93.3% (389/417 bp) identity to Amblyomma testudinarium reported from Japan (LC554788) and 87.4% (368/421 bp) to A. geoemydae from Thailand (KT382864). Phylogenetically, the latter two haplotypes clustered separately from the group of A. integrum collected in Vietnam (Figs. 4, 5). Importantly, the level of 16S rRNA sequence identity was very low (86.1%; 346/402 bp) and the p-distance high (13.9%) between the same isolate (SGL03d) of A. geoemydae from Malaysia (OL616095), which was compared above in the context of cox1 gene sequences.

The only Haemaphysalis species identified in this study, H. cornigera (PP197241), showed 99.5% (636/639 bp) cox1 sequence homology to specimens reported under this name in the southernmost province of China (Hainan: OQ704682) and Southeastern China (Ganzhou: OP050241). However, in the absence of cox1 sequence from the most closely related species, Haemaphysalis shimoga in GenBank, the nearest phylogenetic relationships of H. cornigera from Vietnam within its species group could not be evaluated based on this genetic marker. Importantly, the 16S rRNA haplotype of H. cornigera from Vietnam (PP197254) was only 94.6–94.8% (402/424–425 bp) identical to the corresponding sequence of H. shimoga reported from Thailand (KC170730) and India (MH044717), and their separate clustering received moderate (67%) bootstrap support (Fig. 5).

Discussion

This study aimed at updating our knowledge on the tick infestation of cattle and buffalos in Vietnam, at the same time initiating the barcoding of ixodid species in this tick diversity hotspot. Previously, 59 species of ixodid ticks were reported to occur in Vietnam (Table 1). The present findings provide morphological and molecular evidence on the occurrence of three more species, which are thus newly recognized as indigenous to the fauna of the country.

From the list of 59 hitherto found ixodid species (Table 1), three species were excluded based of uncertainties in their indigenous or taxonomic status connected to Vietnam. First, Rhipicephalus annulatus was reported on cattle (probably introduced in this way) in Vietnam [63]. However, although the climatic conditions in Vietnam are suitable for its establishment [64], it is not regarded as indigenous [5]. On the other hand, R. annulatus was reported in Southeastern China close to Vietnam [65]; therefore, re-examination of formerly collected material and future monitoring of this ixodid species will be necessary to evaluate its presence in the fauna of Vietnam.

Second, Africaniella (formerly Aponomma) orlovi [66] was originally described from female ticks collected from Burmese python in Vietnam [67], unlike its sister species, Af. transversale reported from ball python in Africa and the Middle East. This species was also reported later in a confirmation of its indigenous status [14] but eventually excluded from the list of native ticks [16]. In the latter study, Af. orlovi was thought to originate from erroneously labeled specimens [16], but later it was still considered (at least provisionally) valid [11, 66]. Therefore, it is an important future task to try to access its specimens from larger snakes in northern Vietnam where the type specimen originated.

Third, Ixodes pilosus was also mentioned to occur in the country [18], but later this was rejected [16]. Nevertheless, in a later project the finding of I. pilosus in Central Vietnam was reported again [68].

The only tick species collected in this study, which provided sufficient numbers of developmental stages and data encompassing several months to evaluate its seasonality, was R. microplus. This species is regarded as the economically most important tick infesting cattle in a worldwide context [69, 70]. Notably, although nowadays it has a global geographical range in the tropics and subtropics, it is thought to originate in Southeast Asia, i.e. the region of Vietnam [71]. Rhipicephalus microplus belongs to the subgenus Boophilus, members of which have a one-host life cycle that can be completed in as short as 3–4 weeks and will typically result in heavy tick burdens [54], as also demonstrated in the present study. Its seasonality in Vietnam appears to be in line with previous studies in the region [72], with peak numbers in the summer. However, the small sample size does not allow to reach final conclusions about the complete seasonal activity of R. microplus in the study region.

Rhipicephalus microplus was genotyped in countries surrounding Vietnam, including Malaysia [73], Cambodia [74], Thailand [75], Myanmar, China [76] and Laos [55]. However, prior to this study, no sequences of R. microplus were available in GenBank from Vietnam, despite successful amplification efforts [25]. According to the results of this study, at least clade A of R. microplus occurs in this country, which is also the predominant genetic lineage in Southeast Asia [73, 76].

Based on literature data, the most important hosts of R. microplus are domestic and wild ungulates, as observed here, but occasionally also carnivores, rodents and even humans (Table 1; [48]). By contrast, the predominant hosts of R. linnaei are dogs [57, 77]. Nevertheless, in the present study, two specimens of this species were also collected from cattle (Table 2). Haplotypes of R. linnaei were reported from countries neighboring Vietnam (e.g. Laos and China: [77]) but discounting one sequence [51] reported as R. sanguineus s.l. from Vietnam, no simultaneous morphological and molecular evidence existed from this country on the occurrence of this species. Therefore, this is the first report on R. linnaei, identified as such in Vietnam.

A third species of the genus R. haemaphysaloides was also collected on one occasion from cattle in this study (Table 2). Typical hosts of this species include cattle as well as companion animals, wild animals and rodents in this geographical region [48]. In Vietnam, R. haemaphysaloides was reported from dogs and rats [48], as well as cattle [14], the latter in line with the present findings. Importantly, phylogenetic analyses of this study as well as of previous reports on this species focusing on Southern or Southeastern Asia [65, 78] reflect well-supported divergence, i.e. sister group relationship between haplotypes from Vietnam, different parts of China and Pakistan. These results suggest the existence of several cryptic or novel species in this taxon (group).

Although the genus Ixodes has the greatest number of species worldwide, only 14 are present in continental Southeast Asia [5]. However, at least 42 Haemaphysalis spp. are indigenous to this region, representing almost half of its ixodid fauna [5]. In other words, 25% of the species in the latter genus occur in this area [5]. Therefore, Southeast Asia is regarded as the major evolutionary center for this genus [79].

Traditionally, the genus Haemaphysalis is subdivided into subgenera. Within the subgenus Kaiseriana, several species occur in Vietnam (Fig. 4) and in neighboring China [80]. Among these, H. shimoga was reported to occur in Vietnam (Table 1) and in Thailand [81]. On the other hand, its sibling species, H. cornigera, was not found to occur in the latter country but has been reported recently from Hainan Island of China, close to Vietnam [78]. Results of the present study attest that this species should also be added to the fauna of Vietnam. Adults of H. cornigera typically occur on carnivores, Cervidae and Bovidae [11], the latter also confirmed here.

Last but not least, A. integrum was identified here, for the first time, not only in Vietnam but also in the whole Indochinese subregion of Oriental Asia, considering that this species has been hitherto regarded as indigenous to only India and Sri Lanka [82]. In the present study, A. integrum was found on cattle which, together with buffalos, are typical hosts for this ixodid species [82], but it is also a frequent parasite of humans [83]. Based on the cox1 phylogenetic analysis in this study (Fig. 4), it is a sister species of the morphologically similar A. geoemydae. However, these two species might have been confused in the past, as reflected by (i) the contradicting mitochondrial marker sequences of identical isolates of A. geoemydae (e.g. SGL03d) in GenBank: high level of cox1 sequence identity (low p-distance) between a sequence of A. geoemydae deposited in GenBank (OL629478) and of A. integrum reported here whereas a very low level of 16S rRNA gene identity (high p-distance) between the corresponding sequence (OL616095) and of A. integrum reported here; (ii) ambiguous sequences reported under the name of A. geoemydae (e.g. KT382868 designated as A. geoemydae but having 100% sequence identity to the haplotype morphologically identified as A. integrum in this study). Interestingly, morphologically unidentified haplotypes that, based on the present study (Figs. 4, 5) belong to the phylogenetic clade of A. integrum, were reported from Myanmar as Amblyomma sp. [84]. Therefore, it is reasonable to suppose that A. integrum most likely occurs in a much broader geographical range that surrounds Vietnam, including probably the whole of Southeastern Asia.

Conclusions

In this study, three tick species (R. linnaei, A. integrum and H. cornigera) are reported or were identified to the species level for the first time in Vietnam. Considering that none of their hosts were imported into the country, these findings increase the number of indigenous tick species to 62. Clade A of R. microplus and finally R. linnaei from the group of R. sanguineus s. l. occur in the country. There is multiple phylogenetic evidence that different species might exist among ticks reported under the name R. haemaphysaloides in South and East Asia. To our knowledge, this is also the first report of A. integrum in all of Southeast Asia, where this tick species almost certainly has a broad geographical distribution.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences obtained during this study are deposited in GenBank under the following accession numbers. Cox1 gene: PP197235-PP197241, 16S rRNA gene: PP197249-PP197254. All other relevant data are included in the manuscript and the supplementary material or are available upon request by the corresponding author.

References

Jongejan F, Uilenberg G. The global importance of ticks. Parasitology. 2004;129:S3-14. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0031182004005967.

Guglielmone AA, Nava S, Robbins RG. Geographic distribution of the hard ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) of the world by countries and territories. Zootaxa. 2023;5251:1–274. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5251.1.1.

Balian E, Segers H, Lévèque C, Martens K. The freshwater animal diversity assessment: an overview of the results. Hydrobiologia. 2008;595:627–37.

Seyfulina RR, Kartsev VM. On the spider fauna of the Oriental Region: new data from Thailand (Arachnida: Aranei). Arthropoda Sel. 2022;31:115–28. https://doi.org/10.15298/arthsel.31.1.14.

Petney TN, Saijuntha W, Boulanger N, Chitimia-Dobler L, Pfeffer M, Eamudomkarn C, et al. Ticks (Argasidae, Ixodidae) and tick-borne diseases of continental Southeast Asia. Zootaxa. 2019;4558:1–89. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4558.1.1.

Petney TN. A preliminary study of the significance of ticks and tick-borne diseases in South-east Asia. Mitt Österr Ges Tropenmed Parasitol. 1993;15:33–42.

Petney TN, Kolonin GV, Robbins RG. Southeast Asian ticks (Acari: Ixodida): a historical perspective. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:S201–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-007-0687-4.

Petney TN, Keirans JE. Ticks of the genus Ixodes (Acari: Ixodidae) in South-east Asia. Trop Biomed. 1994;11:123–34.

Kolonin GV. Fauna of ixodid ticks of the world. Sofia-Moscow. 2009. Unpaginated.

Clifford CM, Hoogstraal H, Keirans JE. The Ixodes ticks (Acarina: Ixodidae) of Nepal. J Med Entomol. 1975;12:115–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/12.1.115.

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG, Apanaskevich DA, Petney TN, Estrada-Peña A, Horak IG. The hard ticks of the world. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014. p. 738.

Hornok S, Görföl T, Estók P, Tu VT, Kontschán J. Description of a new tick species, Ixodes collaris n. sp. (Acari: Ixodidae), from bats (Chiroptera: Hipposideridae, Rhinolophidae) in Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1608-0.

Hornok S, Murányi D, Kontschán J, Tu VT. Description of the male and the larva of Ixodes collaris Hornok, 2016 with drawings of all stages. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3365-3.

Kolonin GV. Review of the Ixodid tick fauna (Acari: Ixodidae) of Vietnam. J Med Entomol. 1995;32:276–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/32.3.276.

Hoogstraal H, Clifford CM, Saito Y, Keirans JE. Ixodes (Partipalpiger) ovatus Neumann, subgen. nov.: identity, hosts, ecology, and distribution (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1973;10:157–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/10.2.157.

Kolonin GV. New data on ixodid tick fauna of Vietnam. Zool Zhurnal. 2003;82:1019–21.

Grokhovskaya IM, Hoe NH. Contribution to the study of ixodid ticks (Ixodidae) in Vietnam. Meditsinskaya Parazitologiya i Parazitarnye Bolezni. 1968;37:710–5.

Phan Trong C. Ve bet va con trung ky sinh o Viet Nam. Tap 1 (Ixodea). Mo ta va phan loai. Hanoi. 1977, p. 489. (in Vietnamese)

Vongphayloth K, Brey PT, Robbins RG, Sutherland IW. First survey of the hard tick (Acari: Ixodidae) fauna of Nakai District, Khammouane Province, Laos, and an updated checklist of the ticks of Laos. Syst Appl Acarol. 2016;21:166–80. https://doi.org/10.11158/saa.21.2.2.

Hoogstraal H, Santana FJ, Van Peenen PF. Ticks (Ixodoidea) of Mt. Sontra, Danang, Republic of Vietnam. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1968;61:722–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/61.3.722.

Petney TN, Keirans JE. Ticks of the genus Aponomma (Acari: Ixodidae) in South-east Asia. Trop Biomed. 1996;13:167–72.

Robbins RG, Phong B-D, McCormack T, Behler JL, Zwartepoorte HA, Hendrie DB, et al. Four new host records for Amblyomma geoemydae (Cantor) (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) from captive tortoises and freshwater turtles (Reptilia: Testudines) in the Turtle Conservation Center, Cuc Phuong National Park, Vietnam. In: Proc Entomol Soc Washington 2006;108:726–9.

Toumanoff C. Les Tiques (Ixodea) de l’Indochine. Institut Pasteur de l’Indochine, Saigon 1944, p. ii + 220. (in French)

Petney TN, Keirans JE. Ticks of the genera Amblyomma and Hyalomma (Acari: Ixodidae) in South-east Asia. Trop Biomed. 1995;12:45–56.

Huynh LN, Diarra AZ, Pham QL, Le-Viet N, Berenger JM, Ho VH, et al. Morphological, molecular and MALDI-TOF MS identification of ticks and tick-associated pathogens in Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009813. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009813.

Parola P, Cornet JP, Sanogo YO, Miller RS, Thien HV, Gonzalez JP, et al. Detection of Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma spp., Rickettsia spp., and other eubacteria in ticks from the Thai-Myanmar border and Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1600–8. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.41.4.1600-1608.2003.

Hoogstraal H, Wassef HY. Dermacentor (Indocentor) auratus (Acari: Ixodoidea: Ixodidae): hosts, distribution, and medical importance in tropical Asia. J Med Entomol. 1985;22:170–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/22.2.170.

Apanaskevich MA, Apanaskevich DA. Reinstatement of Dermacentor bellulus (Acari: Ixodidae) as a valid species previously confused with D. taiwanensis and comparison of all parasitic stages. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:573–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjv034.

Apanaskevich DA. First description of the nymph and larva of Dermacentor compactus Neumann, 1901 (Acari: Ixodidae), parasites of squirrels (Rodentia: Sciuridae) in southeast Asia. Syst Parasitol. 2016;93:355–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-016-9633-0.

Apanaskevich DA, Apanaskevich MA. Description of a new Dermacentor (Acari: Ixodidae) species from Thailand and Vietnam. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:806–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjv067.

Apanaskevich MA, Apanaskevich DA. Description of new Dermacentor (Acari: Ixodidae) species from Malaysia and Vietnam. J Med Entomol. 2015;52:156–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjv001.

Wassef HY, Hoogstraal H. Dermacentor (Indocentor) steini (Acari: Ixodoidea: Ixodidae): hosts, distribution in the Malay Peninsula, Indonesia, Borneo, Thailand, and Philippines, and New Guinea. J Med Entomol. 1988;25:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/25.5.315.

Hoogstraal H, Wassef HY, Santana FJ, Kuntz RE. Dermacentor (Indocentor) taiwanensis (Acari: Ixodoidea: Ixodidae): hosts and distribution in Taiwan and southern Japan. J Med Entomol. 1986;23:286–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/23.3.286.

Apanaskevich DA, Apanaskevich MA. Description of two new species of Dermacentor Koch, 1844 (Acari: Ixodidae) from Oriental Asia. Syst Parasitol. 2016;93:159–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-015-9614-8.

Hoogstraal H, Dhanda V, Kammah KM. Aborphysalis, a new subgenus of Asian Haemaphysalis ticks; and identity, distribution, and hosts of H. aborensis Warburton (resurrected ) (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). J Parasitol. 1971;57:748–60.

Hoogstraal H, Dhanda V, Bhat HR. Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) anomala Warburton (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae) from India: description of immature stages and biological observations. J Parasitol. 1972;58:605–10. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278216.

Hoogstraal H, Trapido H. Studies on Southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae): species described by Supino in 1897 from Burma, with special reference to H. (Rhipistoma) asiaticus (= H. dentipalpis Warburton and Nuttall). J Parasitol. 1966;52:1172–87.

Hoogstraal H, Kohls GM. Southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). H. bandicota sp. n. from bandicoot rats in Taiwan, Thailand, and Burma. J Parasitol. 1965;51:460–6. https://doi.org/10.2307/3275973.

Hoogstraal H. Identity, hosts, and distribution of Haemaphysalis (Rhipistoma) canestrinii (Supino) (resurrected), the postulated Asian progenitor of the African leachi complex (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). J Parasitol. 1971;57:161–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/3277774.

Hoogstraal H, Wilson N. Studies on Southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). H. (Alloceraea) vietnamensis sp. n., the first structurally primitive haemaphysalid recorded from Southern Asia. J Parasitol. 1966;52:614–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/3276335.

Hoogstraal H, Wassef HY. The Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae) of birds. 3. H. (Ornithophysalis) subgen. n.: definition, species, hosts, and distribution in the Oriental, Palearctic, Malagasy, and Ethiopian faunal regions. J Parasitol. 1973;59:1099–117. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278650.

Hoogstraal H, Trapido H, Kohls GM. Studies on Southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae): the identity, distribution, and hosts of H. (Kaiseriana) hystricis Supino. J Parasitol. 1965;51:467–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/3275974.

Hoogstraal H, El-Kammah KM, Santana FJ, Van Peenen PF. Studies on southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). H. (Kaiseriana) lagrangei Larrousse: identity, distribution, and hosts. J Parasitol. 1973;59:1118–29.

Hoogstraal H, Santana FJ. Haemaphysalis (Kaiseriana) mageshimaensis (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae): human and wild and domestic mammal hosts, and distribution in Japan, Taiwan, and China. J Parasitol. 1974;60:866–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3278920.

Hoogstraal H, Saito Y, Dhanda V, Bhat HR. Haemaphysalis (H.) obesa Larrousse (Ixodoidea: Ixodidae) from northeast India and Southeast Asia: description of immature stages and biological observations. J Parasitol. 1971;57:177–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/3277776.

Trapido H, Hoogstraal H, Varma MG. Status and descriptions of Haemaphysalis p. papuana Thorell (n. comb.) and of H. papuana kinneari Warburton (n. comb.) (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae) of southern Asia and New Guinea. J Parasitol. 1964;50:172–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/3276058.

Hoogstraal H, Trapido H, Kohls GM. Studies on southeast Asian Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae). Speciation in the H. (Kaiseriana) obesa group: H. semermis Neumann, H. obesa Larrousse, H. roubaudi Toumanoff, H. montgomeryi Nuttall, and H. hirsuta sp. n. J Parasitol. 1966;52:169–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/3276410.

Tan LP, Hamdan RH, Hassan BNH, Reduan MFH, Okene IA, Loong SK, et al. Rhipicephalus tick: a contextual review for Southeast Asia. Pathogens. 2021;10:821. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10070821.

Shi X, Hu C, Soderholm J, Chapman J, Mao H, Cui K, et al. Prospects for monitoring bird migration along the East Asian–Australasian Flyway using weather radar. Remote Sens Ecol Conserv. 2023;9:169–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/rse2.307.

Hornok S, Estrada-Peña A, Kontschán J, Plantard O, Kunz B, Mihalca AD, et al. High degree of mitochondrial gene heterogeneity in the bat tick species Ixodes vespertilionis, I. ariadnae and I. simplex from Eurasia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-1056-2.

Nguyen VL, Colella V, Iatta R, Bui KL, Dantas-Torres F, Otranto D. Ticks and associated pathogens from dogs in northern Vietnam. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:139–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-018-6138-6.

Trapido H, Hoogstraal H. Haemaphysalis cornigera shimoga subsp. n. from Southern India (Ixodea, Ixodidae). J Parasitol. 1964;50:303–10.

Voltzit OV, Keirans JE. A review of Asian Amblyomma species (Acari, Ixodida, Ixodidae). Acarina. 2002;10:95–136.

Walker AR, Bouattour A, Camicas J-L, Estrada-Peña A, Horak I, Latif A, et al. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa: a guide to identification of species. University of Edinburgh. 2003, p. 221.

Kanduma EG, Emery D, Githaka NW, Nguu EK, Bishop RP, Šlapeta J. Molecular evidence confirms occurrence of Rhipicephalus microplus Clade A in Kenya and sub-Saharan Africa. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13:432. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04266-0.

Kazim AR, Low VL, Houssaini J, Tappe D, Heo CC. Morphological abnormalities and multiple mitochondrial clades of Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides (Ixodida: Ixodidae). Exp Appl Acarol. 2022;87:133–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-022-00731-w.

Šlapeta J, Halliday B, Chandra S, Alanazi AD, Abdel-Shafy S. Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826) recognised as the “tropical lineage” of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato: neotype designation, redescription, and establishment of morphological and molecular reference. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022;13:102024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.102024.

Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mel Mar Biol Biot. 1994;3:294–9.

Lv J, Wu S, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Feng C, Jia G, et al. Development of a DNA barcoding system for the Ixodida (Acari: Ixodida). Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25:142–9. https://doi.org/10.3109/19401736.2013.792052.

Black WC, Piesman J. Phylogeny of hard and soft-tick taxa (Acari: Ixodida) based on mitochondrial 16S rDNA sequences. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10034–8.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw054.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38:3022–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120.

Chien NTH, Linh BK, Van Tho N, Hieu DD, Lan NT. Status of cattle ticks infection in yellow and dairy cows in Ba Vi District. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Agriculture Development in the Context of International Integration: Opportunities and Challenges, Hanoi, Vietnam, 7–8 December 2016; p. 115–9.

Okely M, Al-Khalaf AA. Predicting the potential distribution of the cattle fever tick Rhipicephalus annulatus (Acari: Ixodidae) using ecological niche modeling. Parasitol Res. 2022;121:3467–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-022-07670-w.

Li LH, Zhang Y, Wang JZ, Li XS, Yin SQ, Zhu D, et al. High genetic diversity in hard ticks from a China–Myanmar border county. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:469. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-3048-5.

Hornok S, Kontschán J, Takács N, Chaber AL, Halajian A, Abichu G, et al. Molecular phylogeny of Amblyomma exornatum and Amblyomma transversale, with reinstatement of the genus Africaniella (Acari: Ixodidae) for the latter. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101494.

Kolonin GV. Aponomma orlovi sp. n., a new species of ixodid ticks (Acarina, Ixodidae) from Vietnam. Folia Parasitol. 1992;39:93–4.

Dang TD. Complimental investigation of species component of ectoparasites in Tay Nguyen. Final Report (Department of Science and Technology in Gia Lai Province, Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology Tay Nguyen), 2009. (in Vietnamese)

Estrada-Peña A, Bouattour A, Camicas JL, Guglielmone A, Horak I, Jongejan F, et al. The known distribution and ecological preferences of the tick subgenus Boophilus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Africa and Latin America. Exp Appl Acarol. 2006;38:219–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-006-0003-5.

Giles JR, Peterson AT, Busch JD, Olafson PU, Scoles GA, Davey RB, et al. Invasive potential of cattle fever ticks in the southern United States. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:189. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-189.

Barré N, Uilenberg G. Spread of parasites transported with their hosts: case study of two species of cattle tick. Rev Sci Tech. 2010;29:135–47.

Nithikathkul C, Polseela P, Changsap B, Leemingsawat S. Ixodid ticks on domestic animals in Samut Prakan Province, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33:41–4.

Low VL, Tay ST, Kho KL, Koh FX, Tan TK, Lim YA, et al. Molecular characterisation of the tick Rhipicephalus microplus in Malaysia: new insights into the cryptic diversity and distinct genetic assemblages throughout the world. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:341. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0956-5.

Burger TD, Shao R, Labruna MB, Barker SC. Molecular phylogeny of soft ticks (Ixodida: Argasidae) inferred from mitochondrial genome and nuclear rRNA sequences. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:195–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.10.009.

Aung A, Kaewlamun W, Narapakdeesakul D, Poofery J, Kaewthamasorn M. Molecular detection and characterization of tick-borne parasites in goats and ticks from Thailand. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2022;13:101938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2022.

Roy BC, Estrada-Peña A, Krücken J, Rehman A, Nijhof AM. Morphological and phylogenetic analyses of Rhipicephalus microplus ticks from Bangladesh, Pakistan and Myanmar. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2018;9:1069–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.03.035.

Šlapeta J, Chandra S, Halliday B. The, “tropical lineage” of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato identified as Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audouin, 1826). Int J Parasitol. 2021;51:431–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.

Intirach J, Lv X, Han Q, Lv ZY, Chen T. Morphological and molecular identification of hard ticks in Hainan Island, China. Genes. 2023;14:1592. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes14081592.

Hoogstraal H, Kim KC. Tick and mammal coevolution, with emphasis on Haemaphysalis. In: Kim KC, editor. Coevolution of parasitic arthropods and mammals. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1985. p. 505–68.

Yi S, Rong-Man X, Chuan-Chuan W. Haemaphysalis ticks (Ixodoidea, Ixodidae) in China systematic and key to subgenera. Acta Parasitol Med Entomol Sin. 2011;18:251–8. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1005-0507.2011.04.011.

Tanskull P, Inlao I. Keys to the adult ticks of Haemaphysalis Koch, 1844, in Thailand with notes on changes in taxonomy (Acari: Ixodoidea: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1989;26:573–601. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/26.6.573.

Apanaskevich DA, Bandaranayaka KO, Apanaskevich MA, Rajakaruna RS. Redescription of Amblyomma integrum adults and immature stages. Med Vet Entomol. 2016;30:330–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/mve.12178.

Guglielmone AA, Robbins RG. Hard ticks (Acari: Ixodida: Ixodidae) parasitizing humans: a global overview. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 314. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95552-0.

Mohamed WMA, Moustafa MAM, Thu MJ, Kakisaka K, Chatanga E, Ogata S, et al. Comparative mitogenomics elucidates the population genetic structure of Amblyomma testudinarium in Japan and a closely related Amblyomma species in Myanmar. Evol Appl. 2022;15:1062–78. https://doi.org/10.1111/eva.13426.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Veronika Lili Németh for her help. The authors are grateful for the opportunity to use the VHX-5000 digital microscope at the Plant Protection Institute (HUN-REN Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungary) which took most of pictures and also, to Dr. Ai Takano (Yamaguchi University, Japan) for ensuring conditions to take pictures of the Haemaphysalis cornigera sample from Vietnam using the same type of microscope in Japan.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Veterinary Medicine. This study was performed and funded in the frame of the project 2019-2.1.12-TÉT VN-2020-00012 and project no. NDT/HU/22/02 (Decision No. 2822/QD-BKHCN 9 November 2021) supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology (Vietnam). SH, NT and GK were also supported by the Office for Supported Research Groups, Hungarian Research Network (HUN-REN), Hungary (Project No. 1500107).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SH: conceptualization, study design, tick species identification, DNA extraction, manuscript writing. RF: conceptualization, study design, manuscript writing. ND: sample collection, data curation. JK: phylogenetic analysis of cox1 gene, digital photography. NT: PCR tests, sequencing. GK: phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA gene. DP: sample collection, data curation. TD: conceptualization, study design, supervision and coordination of sample collection, tick species identification, manuscript writing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Tick samples were collected from domestic animals during regular veterinary care, therefore no ethical permission was needed.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hornok, S., Farkas, R., Duong, N.N. et al. A morpho-phylogenetic update on ixodid ticks infesting cattle and buffalos in Vietnam, with three new species to the fauna and a checklist of all species indigenous to the country. Parasites Vectors 17, 319 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06384-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-024-06384-5