Abstract

Background

Strongyloidiasis is a soil borne helminthiasis, which in most cases is caused by Strongyloides stercoralis. Human infections with S. fuelleborni fuelleborni and S. fuelleborni kellyi also occur. Although up to 370 million people are currently estimated to be infected with S. stercoralis, this parasite is frequently overlooked. Strongyloides stercoralis is prevalent among humans in Thailand; however, S. fuelleborni fuelleborni has also been reported. Three recent genomic studies of individual S. stercoralis worms found genetically diverse populations of S. stercoralis, with comparably low heterozygosity in Cambodia and Myanmar, and less diverse populations with high heterozygosity in Japan and southern China that presumably reproduce asexually.

Methods

We isolated individual Strongyloides spp. from different localities in northern and western Thailand and determined their nuclear small ribosomal subunit rDNA (18S rDNA, SSU), in particular the hypervariable regions I and IV (HVR-I and HVR-IV), mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) and for a subset whole genome sequences. These sequences were then compared with each other and with published sequences from different geographical locations.

Results

All 237 worms isolated from 16 different human hosts were S. stercoralis, no S. fuelleborni was found. All worms had the common S. stercoralis SSU HVR IV haplotype A. Two different SSU HVR I haplotypes (I and II), both previously described in S. stercoralis, were found. No animal heterozygous for the two haplotypes was identified. Among the twelve cox1 haplotypes found, five had not been previously described. Based upon the mitochondrial cox1 and the nuclear whole genome sequences, S. stercoralis in Thailand was phylogenetically intermixed with the samples from other Southeast Asian countries and did not form its own branch. The genomic heterozygosity was even slightly lower than in the samples from the neighboring countries.

Conclusions

In our sample from humans, all Strongyloides spp. were S. stercoralis. The S. stercoralis from northern and western Thailand appear to be part of a diverse, intermixing continental Southeast Asian population. No obvious indication for genetic sub-structuring of S. stercoralis within Thailand or within the Southeast Asian peninsula was detected.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Strongyloidiasis is a soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) [1]. Although it is recognized as one of the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), it is often overlooked in comparison with other STHs and has therefore by some authors been considered as one of the most neglected NTDs [2,3,4]. Current estimates of the number of people currently infected with Strongyloides stercoralis, the species which causes the vast majority of human strongyloidiasis cases, range from “30–100 million” [1, 5] to “at least 370 million” [3]. Given the difficulties with diagnosis, [1, 6,7,8] the true number may even be considerably higher. Human infections with two other species of Strongyloides, i.e. S. fuelleborni fuelleborni and S. fuelleborni kellyi, have also been reported [1]. Although described as two subspecies of the species S. fuelleborni [9], molecular phylogeny suggests that they are in fact different species [10]. While S. fuelleborni fuelleborni has been found on multiple continents and human infections are generally considered to be zoonotic from non-human primates, S. fuelleborni kellyi appears to be restricted to Papua New Guinea, and so far no animal host has been identified [1].

Over the past few years, the nuclear SSU HVR I, HVR IV and the mitochondrial cox1 loci have emerged as the standard markers for molecular taxonomy within the genus Strongyloides and within the species S. stercoralis [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], and a nomenclature system for the different haplotypes has been proposed and extended. Very recently Barratt et al. [22] compiled the different haplotypes reported by various authors and presented a global survey of S. stercoralis and S. fuelleborni genotypes including newly determined and previously published sequences. A few studies, all analyzing samples from East and Southeast Asia (specifically Cambodia, Myanmar, Japan and southern China), analyzed whole genome data from individual S. stercoralis worms in addition to the SSU and cox1 markers [16, 20, 23]. Based on the mitochondrial cox1 sequences, S. stercoralis in Southeast Asia appears to be very genetically diverse, belonging to a large geographically widespread population, as is illustrated by the fact that many worms isolated from Cambodia [16], Laos [17], Myanmar [18] or Thailand [19], appear more closely related to some individuals isolated on a different continent than to some other worms isolated from the same country or even the same village. Even if only worms isolated from humans are considered, S. stercoralis shows a considerable diversity in the SSU HVR I and IV, loci that in other nematodes appear to be fairly uniform within a given species [16, 18, 20, 24]. Interestingly, except for a presumably asexual population in southern China that might have arisen by a rather recent hybridization event [20], very few [18] or no [16, 24] individuals heterozygous for different SSU haplotypes were found. Nevertheless, whole genome data did not support the hypothesis that different SSU haplotypes represent reproductively isolated populations [16].

In Thailand, S. stercoralis is prevalent in several regions of the country and it is recognized as a serious medical problem. Recently, the prevalence of S. stercoralis infections in the northern, central, northeastern and southern regions were estimated at 0.9–15.9% [25, 26], 2.47% [27], 22.80–32.80% [28, 29] and 0.9–1.7% [30, 31], respectively. To our knowledge, there are two studies providing molecular information about human derived Strongyloides spp. from northeastern Thailand [19, 32]. One of these [19] studied people exposed to non-human primates in two provinces (Maha Sarakham and Udon Thani), and one worm from each positive patient was analyzed. Based on the SSU HVR IV the authors identified as S. fuelleborni fuelleborni one out of the 19 Strongyloides spp. worms isolated. Although this parasite is prevalent in long-tailed macaques in this country [33], this was the first report of a human S. fuelleborni fuelleborni infection in Thailand. The other 18 worms were identified as S. stercoralis. While all of them had the same SSU haplotype, namely HVR IV haplotype A (according to the nomenclature in [16, 22]), at the cox1 locus, the samples fell into 13 different haplotypes. More recently, the cox1 gene and the SSU HVR IV of individual Strongyloides isolated from humans and dogs in two villages of the Kalasin province were sequenced [32]. The authors found that each of the 28 adult worms sequenced from humans (n = 23) and dogs (n = 5) possessed the SSU HVR IV haplotype A. At cox1, the sequences represented eight different haplotypes, of which four were new haplotypes, and found that dogs and humans shared the same haplotypes.

In this study we analyzed the SSU HVR I and IV, the cox1 and the whole genome sequences of Strongyloides spp. isolated from northern and western Thailand. All the Strongyloides specimens tested were S. stercoralis, confirming that human infections with S. fuelleborni fuelleborni are rare. All worms were phylogenetically very close to other samples from the Southeast Asian peninsula and provided no evidence for genetic sub-structuring within Thailand or on the Southeast Asian peninsula. Similar to other samples from this region, these new samples from Thailand showed low heterozygosity, when compared with samples recently described from Japan and southern China [20, 23], further supporting the hypothesis that S. stercoralis on the Southeast Asian peninsula form one intermixing population.

Methods

Collection of S. stercoralis

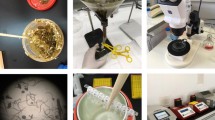

Fresh fecal samples were collected from residents living in the Chiang Mai and Lamphun provinces in northern Thailand and were examined for S. stercoralis infections by using modified kato-katz technique [34], and the modified Baermann technique [21, 35]. In addition, 12 S. stercoralis positive samples of patients living in four provinces in northern Thailand (Chiang Mai, Lamphun, Lampang and Mae Hong Son) and one province (Tak) in western Thailand were included in this study. All patients had visited the Maharaj Nakhon Chiang Mai Hospital between June and November 2018. Fecal samples were examined by the direct fecal smear technique [35] at the laboratory of the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University. To isolate the worms, the samples were cultured by the Harada-Mori technique [35] at ambient temperature for 48–72 h; 95% ethanol was added to the cultured samples and they were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 5 min. After removing the ethanol, worm pellets were transferred and preserved in 95% ethanol at − 20 °C until molecular analysis. The worms were preserved in ethanol as batches (one batch per patient), and later picked individually into 10 μl of water and frozen, as described by Zhou et al. [21].

Worm lysis, SSU and cox1 genotyping

Genotyping at the SSU HVR I, HVR IV and the cox1 loci were performed as described by Zhou et al. [21]. In brief, worms [first-stage larvae (L1s) for field samples and infective third-stage larvae (iL3s) for clinical samples] stored in 10 μl water were frozen and thawed 3 times. Ten microliters of 2× lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.3, 100 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.9% NP-40, 0.9% Tween 20, 240 μg/ml Proteinase K) were added and the samples incubated at 65 °C for 2 h. The worm lysate was then either used directly for genotyping or stored at − 20 °C. Using 2.5 μl of worm lysate as a template, PCR amplification of SSU HVR-I, SSU HVR-IV and cox1 with Taq DNA polymerase (Cat. # M0267; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, USA) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The PCR cycling program was as follows: an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 60 s; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 20 s, annealing for 15 s and extension at 68° C for 90 s; followed by a final extension step at 68 °C for 5 min. The primers and the respective annealing temperatures are listed in Table 1.

Sequence analysis

The SSU and cox1 sequences were analyzed with SeqMan Pro version 12 (Lasergene package; DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI, USA) and checked manually. For S. stercoralis cox1, the same 552-bp product as described in [16] was considered. The cox1 sequences were aligned and phylogenetic analysis was performed as described previously [16] with MEGA7 [36] using ClaustalW for alignment and the neighbor-joining (NJ) and the maximum-likelihood (ML) methods for tree reconstruction, with default settings. The sequence of Necator americanus (GenBank: AJ417719) was used as the outgroup. For comparison, selected published cox1 sequences were also included in the analysis. The corresponding accession numbers and references are listed in the respective figure.

Whole genome sequencing of individual S. stercoralis

Genomic libraries of 15 S. stercoralis (5 first stage larvae, 10 infective larvae) were prepared following the method described previously [21]. In brief, genomic DNA was cleaned up by mixing 20 μl worm lysate with 4 μl magnetic SpeedBeadsTM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) and 16 μl bead buffer (18% PEG8000, 2.5 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0). After DNA clean-up, the DNA was tagmented by mixing 7 μl DNA with 2 μl H2O, 2 μl 5× TAPS-DMF buffer (50 mM TAPS, 25 mM MgCl2, 50% DMF), and 1 μl Tn5 (purchased from Illumina (San Diego, USA) and diluted 1:100 in dialysis buffer -100 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.2, 0.2 M NaCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 20% glycerol). PCR amplification, adapter extension and barcoding were performed by adding 5 μl 5× Q5 reaction buffer, 1 μl 10 mM each dNTPs, 1 μl each of 5 μM Nextera i5 and i7 primer, 0.25 μl Q5 high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Cat. # M0491S; New England BioLabs, Ipswich, USA) and 19.75 μl H2O to the mixture, followed by the thermocycling program: 72 °C for 4 min, 98 °C for 30 s; followed by 17–18 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 15 s, annealing at 67 °C for 20 s, extension at 72 °C for 90 s and cooling to 4 °C. The 300–600 bp fragments of PCR products were selected with beads. Libraries were quantified on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and then sequenced on a Illumina HiSeq 3000 instrument (150-bp paired-end) at the Genome Core facility at the MPI for Developmental Biology (Tübingen, Germany). As part of their service, sequencing adapter sequences were removed by the Genome Core facility staff using the bcl2fastq software (version 2.18.0.12) with user defined parameter barcode-mismatches set to 1. No additional quality filtering was applied. Potential duplicate reads resulting from PCR amplification were removed by the software samtools-rmdup.

Analysis of the whole genome data

Alignment

Raw reads were mapped to the S. stercoralis reference genome (version PRJEB528.WBPS11 from WormBase ParaSite) using bwa mem with default settings [37]. Additional file 1: Table S1 shows an overview of sequencing and alignment steps. In addition to the 15 individual S. stercoralis sequenced in this study, we also included the published whole genome sequences of selected wild isolates from China [20], Cambodia [16], Myanmar and Japan [18, 23] for comparison. To date, these are the only 4 countries from where the whole genomic sequences of individual wild-collected S. stercoralis have been published. Details of sample selection: for Cambodia, Myanmar and Japan, we have selected the same samples (3 and 4, respectively) as included in [20]; for China, we selected only 1 sample, namely the one with the lowest genomic heterozygosity. Since only the homozygous variants were used for the phylogenetic analysis, including more samples with high heterozygosity would have resulted in a large decrease of the number of informative sites.

Variants calling

Variants deviating from the S. stercoralis reference genome were called as described previously [38]. In brief, raw variants were called using the mpileup, bcftools, and vcfutils.pl programs of the samtools suite (version 0.1.18) [39] and filtered for variants with quality values ≥ 20. These variant calls integrate information such as base quality, coverage, and alignment quality. The accuracy of this procedure was previously assessed by comparison with whole genome Sanger sequencing data yielding an agreement of 98% [38]. For analysis of population structure, all variant sites were pooled and called in all samples in order to get the full genotypic data including reference alleles.

Population structure

The genome-wide phylogeny was computed by the neighbor-joining method as implemented in the phangorn package in R [40] and is based on 1315 variant sites (sites with indels in any of the samples were ignored) that were called as homozygous in all samples (see [38, 41] for further details).

Heterozygosity

To estimate heterozygosity, we defined heterozygous sites based on a positive FQ value and a quality value ≥ 20 in the vcf file that was generated by samtools, we then divided the number of heterozygous sites by the total amount of autosomal and sex chromosomal contigs in the S. stercoralis assembly. Only samples comprising > 80% of genomic regions with at least 15× depth were included.

Results and discussion

Phylogenetic position of the new samples based on the SSU and cox1

First, we determined the SSU HVR I, HVR IV and cox1 sequences of the newly isolated samples from northern and western Thailand and compared them with each other and with previously published sequences. All worms had SSU HVR IV haplotype A (nomenclature as proposed by [16, 22]), indicating that they all were S. stercoralis and not S. fuelleborni. Among the 144 worms representing 16 different persons (1–15 worms per host individual), we found two different HVR I haplotypes (Table 2), namely haplotype I, which was proposed to be the ancestral haplotype [16] and haplotype II, which was the most common haplotype among S. stercoralis from humans in northern Cambodia [16, 24]. Similarly, haplotype II was the predominant haplotype (138 of 144 worms) in this study. Haplotype I was found in only 2 of the 16 patients, and within these patients, in 6 out of 9 worms.

Partial sequences (552 bp) of the mitochondrial cox1 gene were obtained from 237 S. stercoralis, representing all four positive human hosts in the village and twelve of the patients from a local hospital. In total, 12 haplotypes were identified in this study. Five of these haplotypes (H1-H5) had not been reported before in S. stercoralis, three haplotypes (H6, H7, H11) have been observed before but not in Thailand and the remaining four haplotypes have been observed in S. stercoralis in Thailand (Table 2). Interestingly, all six worms with SSU HVR haplotype I shared the same cox1 haplotype (H9). To examine the phylogenetic relationships, we reconstructed neighbor-joining and maximum-likelihood trees with our data and selected published cox1 sequences [20] (Fig. 1). Our cox1 haplotypes distributed among the ones found in Southeast Asian countries (Thailand, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia) and did not group into different clades according to their country of origin.

cox1 gene neighbor-joining tree of different S. stercoralis isolates based on 552-bp partial sequences. Shown are the sequences found in this study (green box) and selected published S. stercoralis haplotypes representing the major phylogenetic groups described in recent S. stercoralis cox1 phylogenies. The scale-bar represents 0.02 substitutions per site. The bootstrap values represent 1000 bootstrapping repetitions. Bootstrap values for neighbor-joining and maximum likelihood analysis are shown above or near the branches. The labels are composed as follows: author of the reference; haplotypes names according to this reference; host the isolate was derived from; country the isolate was isolated from; GenBank accession number. The host a particular sequence was found in is further highlighted with a red filled circle for “human” and a blue filled square for “dog”. The two columns on the right indicate the SSU HVR-I and HVR-IV haplotypes found among the worm individuals of the respective cox1 haplotype according to the respective authors, if known. Published sequences can be found under the following references [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]

Whole genome analysis

For 15 worms from northern Thailand, we determined the genome sequences and compared them to the published data (Fig. 2). First, we conducted a phylogenetic analysis based on the whole genome sequences. In full agreement with the mitochondrial cox1 data, the worms from Thailand grouped clearly with the other worms from the Southeast Asian peninsula without forming their own subgroup. In two cases, we sequenced worms from the same patient but found a different SSU HVR I haplotype (haplotypes I and II). In one of these cases (patient S19), the genomes of the two worms were almost identical, suggesting that these two worms must have been very closely related. However, in the other case (patient S12), the two worms were comparably far apart, with the worm that had the common SSU HVR I haplotype II (S12_14) being removed from all the others, while the other with the comparatively rare SSU HVR I haplotype I (S12_11), grouping very closely with other samples. This result represents additional very strong evidence that the different SSU HVR I haplotypes do not represent reproductively isolated populations [16, 20]. As an additional genomic feature, we studied the heterozygosity of the individual worms, because previous studies had found differences in heterozygosity between samples from the Southeast Asian peninsula and populations in Japan [23] and southern China [20], which presumably reproduce largely or exclusively asexually (Fig. 3). We found that the new samples from Thailand clustered with the other samples from the Southeast Asian peninsula, generally towards the lower end of this group, particularly in respect to the heterozygosity on the X-chromosome.

Phylogenetic tree based on whole genome sequences. Sequences newly determined for this study are highlighted in color, followed by the cox1 haplotype number and the SSU HVR-I and HVR-IV haplotypes in parentheses. The colors indicate the provinces: red, Chiang Mai; blue, Lamphun; green, Lampang; grey, Mae Hong Son; yellow, Tak. For comparison, selected published S. stercoralis whole genome sequences described in recent whole genome-based S. stercoralis phylogenies are shown (not highlighted). Samples ending with “cam” are from Cambodia [16]. Samples starting with “My” and “Rk” are from Myanmar and Japan, respectively [23]. Sample cn-379 is from southern China [20]. sste_f1_ERR422406 is a free-living female of the S. stercoralis reference isolate [42]. If listed in the corresponding reference, the SSU HVR-I and HVR-IV haplotypes are indicated in parentheses (note that HVR-IV haplotype C in [20] is the same as HVR-IV haplotype E in [12]; this was noticed by Barratt et al. [22] and occurred because the two publications appeared almost simultaneously). Key for comparing samples from Cambodia with figure 4 of [20]: sste3_cam to sste26_cam correspond to Kh-3 to Kh-26; sste_DC51FLfemale1_cam = Kh-27; sste_DC51FLfemale2_cam = Kh-28; sste_DC51FLmale1_cam = Kh-29; sste_DC51FLmale3_cam = Kh-30; sste_DC69FLmale1_cam = Kh-31; sste_DC69FLmale3_cam = Kh-32; sste_DC69FLmale4_cam = Kh-33

Heterozygosity of individual S. stercoralis. The heterozygosity on the autosomes is plotted against the heterozygosity on the X chromosome. For comparison, published data from S. stercoralis individuals from different geographical locations are included. Cn, China [20]; Kh, Cambodia [16]; My, Myanmar; Rk, Japan (both [23]); Thai, Thailand (present study); US-Ref, USA-derived reference laboratory strain PV001 [42]. For Cn, Kh, My, Rk and the USA reference, the same samples as in Fig. 5 of [20] are included. For Thailand, all samples in Fig. 2 that fulfilled the read coverage criteria (see Methods) were included in this analysis

Conclusions

Similar to an earlier study in Cambodia [16], we found that different SSU HVR I haplotypes were not indicative for genetic isolation as judged by whole genome sequencing. This leaves open the question, as to why, as in Cambodia, we did not find individuals heterozygous for different SSU HVR I haplotypes. Based on nuclear SSU, mitochondrial cox1 and whole genome sequence information, S. stercoralis in northern and western Thailand appear to be part of a genetically diverse continental Southeast Asian population. This is in contrast to two presumably genetically more isolated local populations recently described in Japan [18, 23] and southern China [20] and rather suggests strong mixing of S. stercoralis over the entire mainland Southeast Asian region.

Availability of data and materials

The cox1 DNA sequences obtained in this study are available under the GenBank accession numbers MN871994-MN872230. The whole genome sequencing data are available under the GenBank SRA accession number PRJNA602131. All other relevant data is within the manuscript and its additional file.

Abbreviations

- HVR:

-

hypervariable region (within the SSU)

- iL3:

-

infective third stage larva

- NTD:

-

neglected tropical disease

- SSU :

-

small ribosomal subunit rDNA (encodes the 18S ribosomal RNA

- STH:

-

soil-transmitted helminthiasis

References

Nutman TB. Human infection with Strongyloides stercoralis and other related Strongyloides species. Parasitology. 2017;144:263–73.

Albonico M, Becker SL, Odermatt P, Angheben A, Anselmi M, Amor A, et al. StrongNet: an international network to improve diagnostics and access to treatment for strongyloidiasis control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004898.

Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Montresor A, Requena-Mendez A, Munoz J, Krolewiecki AJ, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2214.

Olsen A, van Lieshout L, Marti H, Polderman T, Polman K, Steinmann P, et al. Strongyloidiasis - the most neglected of the neglected tropical diseases? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:967–72.

Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, Geiger SM, Loukas A, Diemert D, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521–32.

Page W, Speare R. Chronic strongyloidiasis—don’t look and you won’t find. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45:40–4.

Schär F, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Vounatsou P, Marti H, et al. Occurrence of and risk factors for Strongyloides stercoralis infection in South-East Asia. Acta Trop. 2016;159:227–38.

Schär F, Odermatt P, Khieu V, Panning M, Duong S, Muth S, et al. Evaluation of real-time PCR for Strongyloides stercoralis and hookworm as diagnostic tool in asymptomatic schoolchildren in Cambodia. Acta Trop. 2013;126:89–92.

Viney ME, Ashford RW, Barnish G. A taxonomic study of Strongyloides Grassi, 1879 (Nematoda) with special reference to Strongyloides fuelleborni von Linstow, 1905 in man in Papua New Guinea and the description of a new subspecies. Syst Parasitol. 1991;18:95–109.

Dorris M, Viney ME, Blaxter ML. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the genus Strongyloides and related nematodes. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:1507–17.

Basso W, Grandt LM, Magnenat AL, Gottstein B, Campos M. Strongyloides stercoralis infection in imported and local dogs in Switzerland: from clinics to molecular genetics. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:255–66.

Beknazarova M, Barratt JLN, Bradbury RS, Lane M, Whiley H, Ross K. Detection of classic and cryptic Strongyloides genotypes by deep amplicon sequencing: a preliminary survey of dog and human specimens collected from remote Australian communities. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007241.

Hasegawa H, Hayashida S, Ikeda Y, Sato H. Hyper-variable regions in 18S rDNA of Strongyloides spp. as markers for species-specific diagnosis. Parasitol Res. 2009;104:869–74.

Hasegawa H, Kalousova B, McLennan MR, Modry D, Profousova-Psenkova I, Shutt-Phillips KA, et al. Strongyloides infections of humans and great apes in Dzanga-Sangha Protected Areas, Central African Republic and in degraded forest fragments in Bulindi. Uganda. Parasitol Int. 2016;65:367–70.

Hasegawa H, Sato H, Fujita S, Nguema PP, Nobusue K, Miyagi K, et al. Molecular identification of the causative agent of human strongyloidiasis acquired in Tanzania: dispersal and diversity of Strongyloides spp. and their hosts. Parasitol Int. 2010;59:407–13.

Jaleta TG, Zhou S, Bemm FM, Schar F, Khieu V, Muth S, et al. Different but overlapping populations of Strongyloides stercoralis in dogs and humans—dogs as a possible source for zoonotic strongyloidiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005752.

Laymanivong S, Hangvanthong B, Insisiengmay B, Vanisaveth V, Laxachack P, Jongthawin J, et al. First molecular identification and report of genetic diversity of Strongyloides stercoralis, a current major soil-transmitted helminth in humans from Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:2973–80.

Nagayasu E, Aung M, Hortiwakul T, Hino A, Tanaka T, Higashiarakawa M, et al. A possible origin population of pathogenic intestinal nematodes, Strongyloides stercoralis, unveiled by molecular phylogeny. Sci Rep. 2017;7:4844.

Thanchomnang T, Intapan PM, Sanpool O, Rodpai R, Tourtip S, Yahom S, et al. First molecular identification and genetic diversity of Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni in human communities having contact with long-tailed macaques in Thailand. Parasitol Res. 2017;116:1917–23.

Zhou S, Fu X, Pei P, Kucka M, Liu J, Tang L, et al. Characterization of a non-sexual population of Strongyloides stercoralis with hybrid 18S rDNA haplotypes in Guangxi, southern China. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007396.

Zhou S, Harbecke D, Streit A. From the feces to the genome: a guideline for the isolation and preservation of Strongyloides stercoralis in the field for genetic and genomic analysis of individual worms. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:496.

Barratt JLN, Lane M, Talundzic E, Richins T, Robertson G, Formenti F, et al. A global genotyping survey of Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni using deep amplicon sequencing. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007609.

Kikuchi T, Hino A, Tanaka T, Aung MP, Afrin T, Nagayasu E, et al. Genome-wide analyses of individual Strongyloides stercoralis (Nematoda: Rhabditoidea) provide insights into population structure and reproductive life cycles. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0005253.

Schär F, Guo L, Streit A, Khieu V, Muth S, Marti H, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis genotypes in humans in Cambodia. Parasitol Int. 2014;63:533–6.

Nontasut P, Muennoo C, Sa-nguankiat S, Fongsri S, Vichit A. Prevalence of Strongyloides in northern Thailand and treatment with ivermectin vs albendazole. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36:442–4.

Wijit A, Saeung A. Prevalence of the liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, and minute intestinal flukes based on human copro-DNA diagnosis in the upper northern region of Thailand. In: Final Report: Institute of Research, Knowledge Management and Standards for Disease Control; 2017. p. 49.

Jongwutiwes U, Waywa D, Silpasakorn S, Wanachiwanawin D, Suputtamongkol Y. Prevalence and risk factors of acquiring Strongyloides stercoralis infection among patients attending a tertiary hospital in Thailand. Pathog Glob Health. 2014;108:137–40.

Laoraksawong P, Sanpool O, Rodpai R, Thanchomnang T, Kanarkard W, Maleewong W, et al. Current high prevalences of Strongyloides stercoralis and Opisthorchis viverrini infections in rural communities in northeast Thailand and associated risk factors. BMC Pub Health. 2018;18:940.

Prasongdee TK, Laoraksawong P, Kanarkard W, Kraiklang R, Sathapornworachai K, Naonongwai S, et al. An eleven-year retrospective hospital-based study of epidemiological data regarding human strongyloidiasis in northeast Thailand. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:627.

Punsawad C, Phasuk N, Bunratsami S, Thongtup K, Siripakonuaong N, Nongnaul S. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection and associated risk factors among village health volunteers in rural communities of southern Thailand. BMC Pub Health. 2017;17:564.

Wongsaroj T, Nithikathkul C, Rojkitikul W, Nakai W, Royal L, Rammasut P. Brief communication (Original). National survey of helminthiasis in Thailand. Asian Biomed. 2014;8:779–783.

Sanpool O, Intapan PM, Rodpai R, Laoraksawong P, Sadaow L, Tourtip S, et al. Dogs are reservoir hosts for possible transmission of human strongyloidiasis in Thailand: molecular identification and genetic diversity of causative parasite species. J Helminthol. 2019;94:e110.

Thanchomnang T, Intapan PM, Sanpool O, Rodpai R, Sadaow L, Phosuk I, et al. First molecular identification of Strongyloides fuelleborni in long-tailed macaques in Thailand and Lao People’s Democratic Republic reveals considerable genetic diversity. J Helminthol. 2019;93:608–15.

Katz N, Chaves A, Pellegrino J. A simple device for quantitative stool thick-smear technique in schistosomiasis mansoni. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 1972;14:397–400.

Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040–7.

Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 70 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–4.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95.

Rödelsperger C, Neher RA, Weller AM, Eberhardt G, Witte H, Mayer WE, et al. Characterization of genetic diversity in the nematode Pristionchus pacificus from population-scale resequencing data. Genetics. 2014;196:1153–65.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9.

Schliep KP. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:592–3.

Rödelsperger C, Meyer JM, Prabh N, Lanz C, Bemm F, Sommer RJ. Single-molecule sequencing reveals the chromosome-scale genomic architecture of the nematode model organism Pristionchus pacificus. Cell Rep. 2017;21:834–44.

Hunt VL, Tsai IJ, Coghlan A, Reid AJ, Holroyd N, Foth BJ, et al. The genomic basis of parasitism in the Strongyloides clade of nematodes. Nat Genet. 2016;48:299–307.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dorothee Harbecke and the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology genome center and its staff for excellent technical support. We thank Alex Dulovic for critically reading the manuscript and language editing.

Funding

This work was funded by grants from the Royal Golden Jubilee (RGJ) PhD Programme (grant number PHD/0094/2559) under the Thailand Research Fund to KA and ASa, the Distinguished Research Professor Grant Thailand Research Fund (grant number DPG6280002) and Khon Kaen University Grant to Wanchai Maleewong (sub-project to ASa), and by the Max-Planck-Society (departmental core budget to ASt). The funders had no influence on the design of the study, the data collection, analysis and interpretation or writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KA, SZ, ASa and ASt designed the study. KA, AW, KS and ASa collected the samples. KA performed the molecular analysis, with the help and under the supervision of SZ, largely during a research stay in the laboratory of ASt, made possible by the Royal Golden Jubilee (RGJ) PhD Program. KA, SZ and CR performed the bioinformatic analysis of the data. KA, ASa and ASt wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors. ASt and ASa coordinated the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol for S. stercoralis collection from participants was conducted with the approval of the research ethics committee of Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University (No. exemption-6815/2019).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Overview of sequencing data. The first two columns denote sample names and accessions in the European Nucleotide Archive. The third column indicates the total number of raw reads (paired end reads are counted as two reads). The fourth column indicates the number of aligned reads. The numbers of aligned may vary substantially due to different levels of contamination by bacteria and host tissue.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Aupalee, K., Wijit, A., Singphai, K. et al. Genomic studies on Strongyloides stercoralis in northern and western Thailand. Parasites Vectors 13, 250 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04115-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04115-0