Abstract

Background

Ticks are important carriers of many different zoonotic pathogens. To date, there are many studies about ticks and tick-borne pathogens (TBP), but only a few were carried out in Bulgaria. The present study intends to detect the prevalence of tick-borne bacteria and parasites occurring at the Black Sea in Bulgaria to evaluate the zoonotic potential of the tick-borne pathogens transmitted by ticks in this area.

Methods

In total, cDNA from 1541 ticks (Dermacentor spp., Haemaphysalis spp., Hyalomma spp., Ixodes spp. and Rhipicephalus spp.) collected in Bulgaria by flagging method or from hosts was tested in pools of ten individuals each for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Babesia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.), Rickettsia spp. and “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” via conventional and quantitative real-time PCR. Subsequently, samples from positive pools were tested individually and a randomized selection of positive PCR samples was purified, sequenced, and analyzed.

Results

Altogether, 23.2% of ticks were infected with at least one of the tested pathogens. The highest infection levels were noted in nymphs (32.3%) and females (27.5%). Very high prevalence was detected for Rickettsia spp. (48.3%), followed by A. phagocytophilum (6.2%), Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) (1.7%), Babesia spp. (0.4%) and “Ca. Neoehrlichia mikurensis” (0.1%). Co-infections were found in 2.5% of the tested ticks (mainly Ixodes spp.). Sequencing revealed the presence of Rickettsia monacensis, R. helvetica, and R. aeschlimannii, Babesia microti and B. caballi, and Theileria buffeli and Borrelia afzelli.

Conclusion

This study shows very high prevalence of zoonotic Rickettsia spp. in ticks from Bulgaria and moderate to low prevalence for all other pathogens tested. One should take into account that tick bites from this area could lead to Rickettsia infection in humans and mammals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well known that ticks are distributed all over the world and may transmit zoonotic diseases. The majority of studies on ticks and tick-borne diseases (TBD) in Europe are focused on central, southern and eastern Europe. Bulgarian studies on this matter are scarce. Little is known about the distribution of different tick species as well as about prevalence of tick-borne pathogens (TBP) such as Rickettsia spp., Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato), “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” (CNM), Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Babesia spp. in ticks from Bulgaria.

Rickettsia spp. are obligate intracellular gram-negative bacteria which may be divided into four groups, i.e. the spotted fever group (SFG), the typhus group, the ancestral group, and the transitional group. Tick-borne rickettsioses are caused by rickettsiae from SFG [1]. Symptoms of spotted fever may include fever, headache, and abdominal pain. The Mediterranean spotted fever (MSF), which is mainly caused by R. conorii, may have a far more severe outcome. MSF is endemic in some regions in Bulgaria, and severe cases have been reported [2, 3]. Ixodes ricinus, Dermacentor reticulatus and Rhipicephalus spp. are mainly involved in the circulation of Rickettsia species in Europe.

Lyme borreliosis (Lyme disease) is the most common tick-borne disease in Bulgaria [4, 5] where B. burgdorferi (s.l.) was found not only in its main vector Ixodes ricinus but additionally in a few Dermacentor marginatus and Haemaphysalis punctata specimens [6]. There are six known genospecies of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) occuring in Bulgaria, i.e. B. afzelii, B. burgdorferi (s.l.), B. garinii, B. lusitaniae, B. spielmanii and B. valaisiana [4]. There are only a few studies on B. burgdorferi (s.l.) in ticks from Bulgaria; however, these studies report high prevalence rates (32–40%) [4, 7].

“Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” (CNM) is also a gram-negative, obligate intracellular bacterium transmitted by ticks that are of considerable risk for human and animal health [8,9,10]. To our knowledge, the occurrence of CNM has not been reported in Bulgaria thus far.

Anaplasma phagocytophilum is a gram-negative obligate intracellular bacterium belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae. In Europe, A. phagocytophilum is mainly transmitted by I. ricinus. To our knowledge, only one study from Bulgaria examined A. phagocytophilum in I. ricinus ticks, with a surprisingly high prevalence (35%) [7].

Babesia spp. are single-celled Apicomplexa which parasitize erythrocytes and may cause babesiosis in humans, horses, dogs and cattle. Ticks such as Rhipicephalus sanguineus, I. ricinus and D. reticulatus are the most important vectors for several different Babesia species in Bulgaria [11].

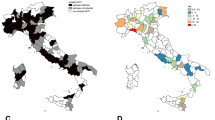

To our knowledge, until now, most of the studies examining ticks and tick-borne pathogens in Bulgaria were conducted on small sample sizes mainly from central Bulgaria [4, 5, 12]. The current study is focused on ticks from the largest protected area in Bulgaria, Strandja Nature Park, which is located in the south-eastern part of the country at the Black Sea [13]. It is often frequented by visitors for leisure activities in the natural surroundings and thus of public health relevance.

As knowledge is lacking on the distribution of ticks and tick-borne bacteria and parasites in this area, the aim of this study was to examine the prevalence of tick-borne pathogens in ticks occurring in this region.

Methods

PCR-screening for tick-borne bacteria and parasites

cDNA from 1541 ticks collected from the vegetation by flagging method (n = 1140), from humans by human-landing catch (n = 74) and from hosts (n = 327): dogs (n = 56), cattle (n = 83), tortoises (n = 22), goats (n = 20), rodents (n = 60), shrews (n = 1) and hedgehogs (n = 85) in the Burgas Province (south-east Bulgaria) was provided by Ohlendorf et al. (unpublished) (Table 1). A description of sampling sites and sample processing will be published elsewhere. Pooled cDNA samples were screened by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for the presence of Rickettsia spp. targeting the gltA gene (70 bp) [14], B. burgdorferi (s.l.) complex targeting the p41 gene (96 bp) [15], A. phagocytophilum targeting the msp2 gene (77 bp) [16], and CNM targeting the groEL gene (99 bp) [10, 17]. All qPCR reactions were carried out using Mx3000P Real-Time Cycler (Stratagene, Agilent Technologies Deutschland GmbH, Waldbronn, Germany). To detect Babesia spp., a conventional PCR targeting the 18S rRNA gene (411–452 bp) [18] was carried out. This PCR also amplifies DNA of Theileria spp. but is only referred to Babesia spp. in the following text. All positive pools were further analyzed separately, to identify positive samples, except for Rickettsia spp. due to high prevalence. To determine infection levels of Rickettsia spp. in ticks, 563 samples were selected (based on established criteria such as collecting method and location, tick species, development stage and sex) for qPCR. Then randomly selected Rickettsia-positive samples yielding a cycle threshold (Ct) value below 35 were further investigated by a conventional PCR targeting 811 bp of the ompB (the outer membrane protein B) gene [19]. Samples positive for B. burgdorferi (s.l.) by qPCR (Ct < 33) were further examined by single-locus sequence typing targeting the recG gene (722 bp) [20, 21]. Conventional PCRs were carried out in the Eppendorf MasterCycler Gradient Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) and the products were visualized by gel-electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel stained with Midori Green (NIPPON, Genetics, Düren, Germany). Positive conventional PCR products, all for Babesia spp. and a randomized selection for Rickettsia spp. (n = 31) and Borrelia spp. (n = 2), were purified using the NucleoSpin® and PCR Clean-up Kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified PCR products were sequenced commercially (Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung, Leipzig, Germany) with forward and reverse primers used for PCR. Obtained sequences were assembled and analyzed with Bionumerics (Version 7.6) and compared to GenBank entries in NCBI BLAST.

Statistical analysis

Confidence intervals (95%CI) for the prevalence in questing and engorged ticks were determined by the Clopper and Pearson method using the GraphPad Software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, Ca., USA). The Fisher’s exact was applied to test the independence of compared prevalence values.

Results

PCR results and sequence analysis for tick-borne bacteria and parasites from all ticks

In total, 23.2% of all ticks (358 out of 1541) were positive for at least one of the investigated pathogens (Rickettsia spp., B. burgdorferi (s.l.), CNM, A. phagocytophilum, or Babesia spp.).

Among positive subadult life stages (larvae and nymphs, n = 302), the predominant genus was Ixodes spp. (99.7%) and only one individual of Rhipicephalus spp. (0.3%) was found. Infected adult development stages (females and males, n = 56) belonged mostly to Hyalomma spp. (50.8%, n = 31), followed by Ixodes spp. (31.2%, n = 19), Rhipicephalus spp. (16.4%, n = 10) and only one Dermacentor spp. (1.6%). The highest prevalence of investigated TBP was detected for Rickettsia spp. which was significantly more often detected than any other pathogen (48.3%, n = 272, P < 0.001, CI: 45.9–54.28%). But A. phagocytophilum (6.2%, n = 95, P < 0.001, CI: 5.06–7.48%) was still significantly more often detected than B. burgdorferi (s.l.) (1.7%, n = 26), Babesia spp. (0.4%, n = 6), and CNM (0.06%, n = 1).

Rickettsia spp. were found most significantly in I. ricinus (66.6%, n = 237, P < 0.001, CI: 61.52–71.28%), followed by Hyalomma spp., D. marginatus and Rhipicephalus spp. Sequencing of selected samples (n = 31) revealed presence of three Rickettsia species (Table 2): (i) R. monacensis (61.3%, n = 19) showing a similarity from 99 to 100% to three different sequences on GenBank (accession nos. KU961543, EU330640, JN036418), followed by (ii) R. aeschlimannii (25.8%, n = 8) showing 100% identity to a sequence from GenBank (KU961544) and (iii) R. helvetica (12.9%, n = 4) with 100% identity to a GenBank sequence with accession no. KU310591. All R. monacensis and R. helvetica sequences were detected in I. ricinus samples (from vegetation, dogs and goats), while R. aeschlimannii was detected in ticks from dogs and cattle: Hy. anatolicum (n = 1), Hy. excavatum (n = 2), Hy. marginatum (n = 4), and Rhipicephalus spp. (n = 1). Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) was detected only in I. ricinus (1.9%, n = 25) and Ixodes spp. (2.8%, n = 1). Sequenced Borrelia samples (n = 2) belonging to B. afzelii (100% identity with the sequence with the GenBank accession number CP009058) were detected in one I. ricinus tick collected from vegetation and one from a hedgehog. CNM was detected only in one specimen of tested ticks (0.1%, n = 1) which was identified as Ixodes ricinus and collected from vegetation. For A. phagocytophilum the prevalence was significantly higher in Ixodes spp. (38.9%, n = 14, P < 0.001, CI: 24.75–55.17%), than in any other genus. DNA of Babesia spp. was found in 0.4% (n = 6) of investigates ticks and all of them were collected from hosts. Babesia spp. was detected in Hyalomma spp. (100%, n = 1), Hy. marginatum (3.3%, n = 1), R. bursa (3.2%, n = 3) and I. ricinus (0.06%, n = 1). There were two Babesia and one Theileria species found in ticks from the current study: (i) B. microti was detected in I. ricinus from Apodemus flavicollis, the yellow-necked mouse (92% identity with KX591647); (ii) B. caballi in Hy. marginatum from cattle (100% identity with KX375824) and (iii) T. buffeli detected in R. bursa from cattle (showing 100% identity with KX375823). Theileria buffeli was also detected in two Hyalomma spp. (showing 100% identity with KX375822), also from cattle. All ticks infested with Babesia spp. were also infected with other pathogens. Co-infections (Table 3) were detected in 2.5% (n = 39) of tested tick specimens, mainly in Ixodes spp.

Prevalence of tick-borne bacteria and parasites in ticks collected only from vegetation

Ticks collected from vegetation (n = 1214) were positive for four of the five investigated pathogens (Table 4), Rickettsia spp. (59.12%; n = 214), A. phagocytophilum (2.47%; n = 30), B. burgdorferi (s.l.) (0.91%; n = 11) and CNM (0.08%; n = 1) which was detected only in ticks from vegetation. No Babesia spp. infections were detected. The highest diversity of TBP was found among Ixodes spp. (four pathogens). Ticks from vegetation positive for Rickettsia spp., CNM and Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) were exclusively belonging to the genus Ixodes. Moreover, CNM was found only in one tick from vegetation. Ticks positive for A. phagocytophilum were belonging to the genera Ixodes and Rhipicephalus.

Prevalence of tick-borne bacteria and parasites in ticks collected only from hosts

Ticks collected from hosts (n = 327) were infected by four out of the five investigated pathogens (Table 5), A. phagocytophilum (19.88%, n = 65), Rickettsia spp. (28.86%, n = 58), B. burgdorferi (s.l.) (4.59%, n = 15), and Babesia spp. (1.83%, n = 6) which was found only in ticks from hosts. CNM was not detected in ticks from hosts. The highest diversity of TBP was found among Ixodes spp. (four pathogens) and the lowest among Dermacentor spp. (one pathogen). Rickettsia spp. was found in all tick genera collected from hosts (Hyalomma, Ixodes, Rhipicephalus and Dermacentor). The highest prevalence was detected in Ixodes, followed by Hyalomma, Dermacentor and Rhipicephalus. A significantly higher prevalence for Borrelia spp. was found in ticks from small mammals (10.3%, n = 15, P < 0.001, CI: 9.8–30.04%) compared to any other host species.

The prevalence for A. phagocytophilum was significantly higher in ticks from hosts in comparison to ticks from vegetation (19%, n = 65, P < 0.001, CI: 15.9–24.56%). All Anaplasma-positive ticks from hosts belonged to all investigated genera except for Dermacentor spp. The prevalence for B. burgdorferi (s.l.) was significantly higher in ticks from hosts than from vegetation (4.6%, n = 15, P < 0.001, CI: 6.2–16.36%).

Babesia spp. DNA was detected only in ticks from hosts and was significantly more often detected in ticks from one location, Malko Tarnovo (5.75%, n = 5, P < 0.001, CI: 2.16–13.07%), where most ticks were collected from cattle.

Discussion

Until today, studies in Bulgaria were mostly focused on Lyme disease in humans, sheep, cows and dogs [4, 22, 23]. Most studies from Bulgaria on tick-borne pathogens are serological surveys in humans, cattle and dogs [2, 22,23,24] and there are only a few studies investigating ticks for tick-borne pathogens [5, 22, 25]. Further, these studies examined only a small sample size of ticks (n = 94–299) [4, 6, 7, 12]. The current study reports tick-borne bacteria and parasites on a larger scale in a nature park at the Black Sea in Bulgaria with a high frequency of visitors.

Ixodes ricinus was the predominant tick species in this study which is not surprising as it is the most common tick species in the Northern Hemisphere [26]. The infection rate for tick-borne pathogens was also significantly higher in I. ricinus compared to all other tick species, which is not unusual as I. ricinus is known to be the most important vector of tick-borne pathogens in Europe [27].

Rickettsia spp. were found in every tick genus examined. However, a higher diversity of tick species infected by Rickettsia spp. were collected from hosts (ticks belonging to Ixodes, Hyalomma, Dermacentor and Rhipicephalus) than from vegetation (only Ixodes). In general, the prevalence in questing ticks was higher compared to the one obtained from ticks collected from animals. The infection levels in almost all tick genera (Ixodes - both from vegetation and hosts, Hyalomma and Dermacentor from hosts) were very high, i.e. at least 50%, except for Rhipicephalus ticks from hosts which were infected only in few percentage. Interestingly, most Rickettsia-positive ticks collected from small mammals, were parasitizing southern white-breasted hedgehogs, Erinaceus concolor. There are no data about Rickettsia infection in ticks collected from E. concolor but other hedgehog species such as E. europaeus, are known to serve as potential reservoirs for certain Rickettsia spp. from urban and suburban areas [28,29,30]. Sequence analysis revealed a variety of different Rickettsia species such as R. helvetica, R. aeschlimannii and R. monacensis in the current study. All of them are considered as agents of human diseases and occur in Europe [1, 31]. Rickettsia species were detected only in their respective vectors: R. helvetica and R. monacensis were exclusively in I. ricinus, and R. aeschlimannii was found only in Hyalomma spp. [1, 32]. All R. aeschlimannii samples were very closely associated with the Crimean isolate obtained from Hy. marginatum (KU961544, unpublished). Migrating birds from Africa are considered as reservoirs for R. aeschlimannii in Europe and Hyalomma spp. are remarkably contributing to its transmission in southern Europe [32, 33]. The R. helvetica sequences detected in the current study were almost identical with the one previously detected in I. persulcatus from Novosibirsk Region, Russia (KU310591, unpublished). The ubiquitously occurring R. helvetica is mostly transmitted by I. ricinus ticks which are considered as its main vector and reservoir, but it was previously detected also in tissues of many vertebrates, e.g. rodents, hedgehogs, dogs, deer, birds and dogs [1, 34,35,36]. Rickettsia monacensis sequences obtained in this study had a high similarity to (i) a Crimean isolate acquired from Ha. punctata (KU961543, unpublished), (ii) a variant isolated from I. ricinus ticks from Germany (EU330640, unpublished), and (iii) a strain detected in I. ricinus from an urban park in Munich, Germany (JN036418.1; [37]). Widely distributed in Europe, R. monacensis was detected previously not only in I. ricinus ticks but on hosts, mainly migratory birds and lizards [38,39,40,41]. In the current study, R. monacensis was detected in Ixodes ticks collected from the southern white-breasted hedgehogs, Erinaceus concolor for the first time.

Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) was found with a low prevalence (1.7%) compared to other studies (32–37.3%) from Bulgaria [4, 12]. All positive ticks from this study belonged to the genus Ixodes, which is in line with previous studies from Bulgaria. However, there is also a study reporting Borrelia-positive D. marginatus and Ha. punctata which were collected from humans with Lyme disease in Bulgaria [6]. In this study, most Borrelia-positive ticks were collected from small mammals, especially from E. concolor. Sequencing unveiled presence of pathogenic B. afzelii with a 100% identity with a sequence obtained from human skin in Austria (CP009058; [42]). Again, there is no information about Borrelia-infected ticks collected from E. concolor; however, many studies report the prevalence of Borrelia species, including B. afzelii, in ticks collected from other hedgehog species in the neighbouring country Romania [30, 43, 44].

In this study, CNM was found in a single specimen of I. ricinus from vegetation only. To our knowledge, this is the first detection of CNM in Bulgaria. Nevertheless, the prevalence (0.1%) for CNM in this study was lower compared to other studies from central Europe (2.2–45%) [10, 17, 45]. However, results from south-eastern Europe show a similar low prevalence (0–1.3%) leading to the assumption that CNM in ticks is occurring more often in central Europe, where also clinical cases of neoehrlichiosis were reported than in south-eastern Europe where clinical cases are thus far absent [46, 47].

The majority of Anaplasma phagocytophilum-positive ticks in this study belonged to I. ricinus (over 90%), which is in line with other studies from Europe suggesting I. ricinus as the main vector [48, 49]. The current study reports a high prevalence of A. phagocytophilum in ticks collected from small mammals compared to questing ticks and ticks collected from any other animal species. This finding is in contrast to other European studies reporting low or even zero prevalence in ticks collected from small mammal species such as Apodemus spp. and Myodes spp. [45, 50]. However, one should take into account that infected ticks obtained from small mammals in this study were collected mainly from southern white-breasted hedgehogs, E. concolor. There are no available data on Anaplasma infections in ticks from E. concolor but in general, the hedgehog E. europaeus is a suspected reservoir host for A. phagocytophilum [30, 43, 51, 52]. In Romania which is a neighbouring country to Bulgaria, A. phagocytophilum was detected in ticks collected from another hedgehog species, Erinaceus roumanicus with a prevalence of 12% [44].

Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. were found with a remarkable low prevalence in ticks in this study (less than 1%) in comparison to the prevalence in blood samples of dogs and ticks collected from humans and the environment from Bulgaria in previous studies (3.6–31.4%) [11, 24]. Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. were detected only in ticks collected from hosts and were belonging to three genera: Hyalomma, Rhipicephalus and Ixodes, which is not surprising as these tick species are known to be vectors for these protozoans especially in neighbouring countries such as Turkey [53,54,55]. Sequence analysis revealed the presence of three species. Babesia microti detected in I. ricinus from the yellow-necked mouse A. flavicollis,, which is known to serve as a reservoir, was most closely related with an isolate obtained from questing I. ricinus in Kyiv Botanical Garden, Ukraine (KX591647; [56]). Babesia microti is responsible for human babesiosis cases mostly in the USA, but it was also detected in I. ricinus ticks in Europe [57, 58]. However, European strains of B. microti are known to be less pathogenic. Only the ‘Jena’ strain is considered as pathogenic for humans in Europe [57]. The sequences for B. caballi detected in a female Hy. marginatum tick feeding on cattle in the current study, showed the closest similarity to a sequence found as well in a female Hy. marginatum tick collected from vegetation in Italy (KX375824, unpublished). Babesia caballi is known as the etiological agent of equine piroplasmosis, and ticks from following genera have been identified as significant vectors of this protozoon: Boophilus, Dermacentor, Haemaphysalis, Hyalomma and Rhipicephalus [59]. Theileria buffeli detected in R. bursa, and Hyalomma spp. from cattle in the current study was identical with two sequences obtained from R. annulatus nymphs parasitizing cattle in Italy which were most likely misnamed as T. sergenti (KX375822, KX375823; [60]). According to Uilenberg [61], there is confusion in the nomenclature, and T. sergenti should be named as T. buffeli which is responsible for bovine theileriosis worldwide, since the name ‘T. sergenti’ has been used earlier to describe a Theileria species infesting sheep [62, 63].

Altogether, the prevalence in ticks from hosts was higher for most pathogens. Moreover, more tick genera collected from hosts were found to be positive in general in comparison to ticks which were collected from vegetation. These facts point out that the uptake of pathogens during a blood meal on potential reservoir hosts is more probable than the vertical transmission of the pathogen in ticks. Co-infections in ticks were detected in combination with almost all pathogens besides CNM and the combination of infection of Borrelia spp. and Babesia spp. Co-infections have been described for Rickettsia spp., Borrelia spp., Babesia spp. and A. phagocytophilum [45, 64]. As co-infection levels in this study were rather low, no significant combination of pathogens could be found.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study presents the prevalence of tick-borne bacteria and parasites in ticks on a large scale for the first time in a natural reserve in Bulgaria. To our knowledge, this study reports the first detection of “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” and R. aeschlimannii in ticks from Bulgaria. A high diversity of tick-borne pathogens (R. monacensis, A. phagocytophilum and B. afzelii) was detected in ticks collected from the southern white-breasted hedgehog, E. concolor, for the first time suggesting it as a host maintaining circulation of tick-borne pathogens. Although most tick-borne pathogens studied were only found with a low prevalence, the prevalence of Rickettsia spp. was very high and diverse species were found. This may be of health impact as humans may suffer from spotted fever after having a tick bite from this region in Bulgaria.

Abbreviations

- cDNA:

-

complementary DNA

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CNM:

-

"Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis"

- HLC:

-

human-landing catch

- MSF:

-

Mediterranean spotted fever

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- qPCR:

-

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA:

-

ribonucleic acid

- SFG:

-

spotted fever group

- TBD:

-

tick-borne disease

- TBP:

-

tick-borne pathogens

References

Parola P, Paddock CD, Socolovschi C, Labruna MB, Mediannikov O, Kernif T, et al. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: a geographic approach. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:657–702.

Pishmisheva M, Stoycheva M, Vatev N, Semedjiva M. Mediterranean spotted fever in children in the Pazardjik Region, South Bulgaria. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:542–4.

Baymakova M, Pekova L, Parousheva P, Andonova R, Plochev K. Severe clinical forms of Mediterranean spotted fever: a case series from an endemic area in Bulgaria. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2016; https://doi.org/10.2298/VSP160907380B.

Christova I, Schouls L, van de Pol I, Park J, Panayotov S, Lefterova V, et al. High prevalence of granulocytic Ehrlichiae and Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks from Bulgaria. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:4172–4.

Christova I, Dimitrov H, Trifonova I, Gladnishka T, Mitkovska V, Stojanova A, et al. Detection of human tick-borne pathogens in rodents from Bulgaria. Acta Zool Bulg. 2012; Suppl 4:111–114.

Angelov L, Dimova P, Berbencova W. Clinical and Laboratory evidence of the importance of the tick D. marginatus as a vector of B. burgdorferi in some areas of sporadic Lyme disease in Bulgaria. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;12:499–502.

Christova I, van de Pol J, Yazar S, Velo E, Schouls L. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma and Ehrlichia species, and spotted fever group Rickettsiae in ticks from southeastern Europe. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:535–42.

Diniz PPVP, Schulz BS, Hartmann K, Breitschwerdt EB. "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" infection in a dog from Germany. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2059–62.

Li H, Jiang JF, Liu W, Zheng YC, Huo QB, Tang K, et al. Human infection with "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis", China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012;18:1636–9.

Jahfari S, Fonville M, Hengeveld P, Reusken C, Scholte EJ, Takken W, et al. Prevalence of Neoehrlichia mikurensisin ticks and rodents from north-west Europe. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:74.

Ivanov IN, Mitkova N, Reye AL, Hübschen JM, Vatcheva-Dobrevska RS, Dobreva EG, et al. Detection of new Francisella-like tick endosymbionts in Hyalomma spp. and Rhipicephalus spp. (Acari: Ixodidae) from Bulgaria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:5562–5.

Gladnishka TK, Tasseva EI, Christova IS, Nikolov MA, Lazarov SP. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum and spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks from the region of Sofia, Bulgaria (Acari: Parasitiformes: Ixodidae). In: Deltshev C, Stoev P, editors. European arachnology, vol. 58: Acta Zool Bulg. 2005(Suppl. 1):339–43.

Strandja Nature Park: Strandja Nature Park Official Webpage. 2015. http://www.strandja.bg/en. Accessed 1 Nov 2017.

Wölfel R, Essbauer SS, Dobler G. Diagnostics of tick-borne rickettsioses in Germany: a modern concept for a neglected disease. J Med Microbiol. 2008;298:368–74.

Schwaiger M, Peter O, Cassinotti P. Routine diagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) infections using a real-time PCR assay. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2001;7:461–9.

Courtney JW, Kostelnik LM, Zeidner NS, Massung RF. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3164–8.

Silaghi C, Woll D, Mahling M, Pfister K, Pfeffer M. "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" in rodents in an area with sympatric existence of the hard ticks Ixodes ricinus and Dermacentor reticulatus, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:285.

Casati S, Sager H, Gern L, Piffaretti JC. Presence of potentially pathogenic Babesia sp. for human in Ixodes ricinus in Switzerland. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2006;13:65–70.

Roux V, Raoult D. Phylogenetic analysis of members of the genus Rickettsia using the gene encoding the outer-membrane protein rOmpB (ompB). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1449–55.

Wang G, Liveris D, Mukherjee P, Jungnick S, Margos G, Schwartz I. Molecular typing of Borrelia burgdorferi. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2014;34:1–31.

Obiegala A, Król N, Oltersdorf C, Nader J, Pfeffer M. The enzootic life-cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) and tick-borne rickettsiae: an epidemiological study on wild-living small mammals and their ticks from Saxony, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:115.

Zarkov IS, Marinov MM. The Lyme disease: results of a serological study in sheep, cows and dogs in Bulgaria. Revue Méd Vét. 2003;154:363–6.

Pantchev N, Schnyder M, Vrhovec MG, Schaper R, Tsachev I. Current surveys of the seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi, Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Leishmania infantum, Babesia canis, Angiostrongylus vasorum and Dirofilaria immitis in dogs in Bulgaria. Parasitol Res. 2015;114(Suppl. 1):117–30.

Kirkova Z, Iliev P, Vesser M, Knaus M. Survey on ectoparasites of dogs (Canis familiaris) in Bulgaria. Munich: Conference Proceedings, 12th International Symposium of Ectoparasites in Pets; 2013. p. 16.

Mohareb E, Christova I, Soliman A, Younan R, Kantardjiev T. Tick-borne encephalitis in Bulgaria, 2009 to 2012. Euro Surveill. 2013;18:20635.

Gern L. The biology of Ixodes ricinus tick. Ther Umsch. 2005;62:707–12.

Rizzoli A, Silaghi C, Obiegala A, Rudolf I, Hubálek Z, Földvári G, et al. Ixodes ricinus and its transmitted pathogens in urban and peri-urban areas in Europe: new hazards and relevance for public health. Front Public Health. 2014;2:251.

Marié JL, Davoust B, Socolovschi C, Raoult D, Parola P. Molecular detection of rickettsial agents in ticks and fleas collected from a European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) in Marseilles, France. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;35:77–9.

Speck S, Perseke L, Petney T, Skuballa J, Pfäffle M, Taraschewski H, et al. Detection of Rickettsia helvetica in ticks collected from European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus Linnaeus, 1758). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:222–6.

Jahfari S, Ruyts SC, Frazer-Mendelewska E, Jaarsma R, Verheyen K, Sprong H. Melting pot of tick-borne zoonoses: the European hedgehog contributes to the maintenance of various tick-borne diseases in natural cycles urban and suburban areas. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:134.

Parola P, Paddock CD, Raoult D. Tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: emerging diseases challenging old concepts. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:719–56.

Kamani J, Baneth G, Apanaskevich DA, Mumcuoglu KY, Harrus S. Molecular detection of Rickettsia aeschlimannii in Hyalomma spp. ticks from camels (Camelus dromedarius) in Nigeria, West Africa. Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:205–9.

Hornok S, Csörgő T, de la Fuente J, Gyuranecz M, Privigyei C, Meli ML, et al. Synanthropic birds associated with high prevalence of tick-borne rickettsiae and with the first detection of Rickettsia aeschlimannii in Hungary. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13:77–83.

Sprong H, Wielinga PR, Fonville M, Reusken C, Brandenburg AH, Borgsteede F, et al. Ixodes ricinus ticks are reservoir hosts for Rickettsia helvetica and potentially carry flea-borne Rickettsia species. Parasit Vectors. 2009;2:41.

Hornok S, Kováts D, Csörgő T, Meli ML, Gönczi E, Hadnagy Z, et al. Birds as potential reservoirs of tick-borne pathogens: first evidence of bacteraemia with Rickettsia helvetica. Parasite Vectors. 2014;7:128.

Wächter M, Wölfel S, Pfeffer M, Dobler G, Kohn B, Moritz A, et al. Serological differentiation of antibodies against Rickettsia helvetica, R. raoultii, R. slovaca, R. monacensis and R. felis in dogs from Germany by a micro-immunofluorescent antibody test. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:126.

Schorn S, Pfister K, Reulen H, Mahling M, Silaghi C. Occurrence of Babesia spp., Rickettsia spp. and Bartonella spp. in Ixodes ricinus in Bavarian public parks, Germany. Parasit Vectors. 2011;4:135.

Elfving K, Olsen B, Bergström S, et al. Dissemination of spotted fever Rickettsia agents in Europe by migrating birds. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8572.

De Sousa R, de Carvalho IL, Santos AS, et al. Role of the lizard Teira dugesii as a potential host for Ixodes ricinus tick-borne pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:3767–9.

Biernat B, Stańczak J, Michalik J, Sikora B, Cieniuch S. Rickettsia helvetica and R. monacensis infections in immature Ixodes ricinus ticks derived from sylvatic passerine birds in west-central Poland. Parasitol Res. 2016;115:3469–77.

Mărcuţan I-D, Kalmár Z, Ionică AM, D’Amico G, Mihalca AD, Vasile C, Sàndor AD. Spotted fever group rickettsiae in ticks of migratory birds in Romania. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:294.

Schüler W, Bunikis I, Weber-Lehman J, Comstedt P, Kutschan-Bunikis S, Stanek G, et al. Complete genome sequence of Borrelia afzelii K78 and comparative genome analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0120548.

Krawczyk AI, van Leeuwen AD, Jacobs-Reitsma W, Wijnands LM, Bouw E, Jahfari S, et al. Presence of zoonotic agents in engorged ticks and hedgehog faeces from Erinaceus europaeus in (sub) urban areas. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:210.

Dumitrache MO, Paştiu AI, Kalmár Z, Mircean V, Sándor AD, Gherman CM, et al. Northern white-breasted hedgehogs Erinaceus roumanicus as hosts for ticks infected with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in Romania. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:214–7.

Obiegala A, Pfeffer M, Pfister K, Tiedemann T, Thiel C, Balling A, et al. "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" and Anaplasma phagocytophilum: prevalences and investigations on a new transmission path in small mammals and ixodid ticks. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:563.

Hodžić A, Fuehrer HP, Duscher GG. First molecular evidence of zoonotic bacteria in ticks in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2017;64:1313–6.

Raileanu C, Moutailler S, Pavel I, Porea D, Mihalca AD, Savuta G, Vayssier-Taussat M. Borrelia diversity and co-infection with other tick-borne pathogens in ticks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:36.

Stuen S. Anaplasma phagocytophilum - the most widespread tick-borne infection in animals in Europe. Vet Res Commun. 2007;31(Suppl. 1):79–84.

Severinsson K, Jaenson TG, Pettersson J, Falk K, Nilsson K. Detection and prevalence of Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Rickettsia helvetica in Ixodes ricinus ticks in seven study areas in Sweden. Parasit Vectors. 2010;3:66.

Burri C, Schumann O, Schumann C, Gern L. Are Apodemus spp. mice and Myodes glareolus reservoirs for Borrelia miyamotoi, "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis", Rickettsia helvetica, R. monacensis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum? Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:245–51.

Silaghi C, Skuballa J, Thiel C, Pfister K, Petney T, Pfäffle M, et al. The European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) - a suitable reservoir for variants of Anaplasma phagocytophilum? Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2012b;3:49–54.

Földvári G, Jahfari S, Rigó K, Jablonszky M, Szekeres S, Majoros G, et al. "Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis" and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in urban hedgehogs. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:496–8.

Altay K, Aydin MF, Dumanli N, Aktas M. Molecular detection of Theileria and Babesia infections in cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2008;158:295–301.

Aktas M, Vatansever Z, Ozubek S. Molecular evidence for trans-stadial and transovarial transmission of Babesia occultans in Hyalomma marginatum and Rhipicephalus turanicus in Turkey. Vet Parasitol. 2014;204:369–71.

Aydin MF, Aktas M, Dumanli N. Molecular identification of Theileria and Babesia in ticks collected from sheep and goats in the Black Sea region of Turkey. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:65–9.

Didyk YM, Blanarova L, Pogrebnyak S, Akimov I, Petko B, Vichova B. Emergence of tick-borne pathogens (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia raoultii and Babesia microti) in the Kyiv urban parks, Ukraine. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2017;8:219–25.

Gray J, Zintl A, Hildebrandt A, Hunfeld KP, Weiss L. Zoonotic babesiosis: overview of the disease and novel aspects of pathogen identity. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2010;1:3–10.

Welc-Falęciak R, Bajer A, Paziewska-Harris A, Baumann-Popczyk A, Siński E. Diversity of Babesia in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Poland. Adv Med Sci. 2012;57:364–9.

Wise LN, Kappmeyer LS, Mealey RH, Knowles DP. Review of equine piroplasmosis. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27:1334–46.

Toma L, Di Luca M, Mancini F, Severini F, Mariano C, Nicolai G, et al. Molecular characterization of Babesia and Theileria species in ticks collected in the outskirt of Monte Romano, Lazio region, central Italy. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2017;53:30–4.

Uilenberg G. Theileria sergenti. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:386.

Gubbels MJ, Hong Y, van der Weide M, Qi B, Nijman IJ, Guangyuan L, Jongejan F. Molecular characterisation of the Theileria buffeli/orientalis group. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30:943–52.

Liu A, Guan G, Du P, Gou H, Zhang J, Liu Z, et al. Rapid identification and differentiation of Theileria sergenti and Theileria sinensis using a loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay. Vet Parasitol. 2013;191:15–22.

Overzier E, Pfister K, Herb I, Mahling M, Jr BG, Silaghi C. Detection of tick-borne pathogens in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), in questing ticks (Ixodes ricinus), and in ticks infesting roe deer in southern Germany. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:320–8.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Zdravko Dimov for his help in field work and Stoyan Yordanov for administration help. Further, we thank Dana Rüster, Pascal Trippner and Johanna Fürst for their technical assistance. The work of MP and AO was done within the framework of COST action TD1303 EURNEGVEC. Publication of this paper has been sponsored by Bayer Animal Health in the framework of the 13th CVBD World Forum Symposium.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. All data concerning tick collection will be published separately. The sequences were submitted to the GenBank database under the accession numbers MG972813-MG972850.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MP and AO organized and planned the study. SJ and CD organized and funded the fieldwork for the collection of wildlife samples. VO and MM collected ticks. VO carried out the morphologic determination of ticks. AO, NK, VO and JN prepared the samples in the laboratory. AO, NK and JN tested the samples for tick-borne pathogens. AO performed the sequence analysis. AO, JN, NK and MP drafted the manuscript and wrote the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Nader, J., Król, N., Pfeffer, M. et al. The diversity of tick-borne bacteria and parasites in ticks collected from the Strandja Nature Park in south-eastern Bulgaria. Parasites Vectors 11, 165 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2721-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2721-z