Abstract

Sodium benzoate (SB) is widely used as a preservative in food industry, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a major carrier protein similar to human serum albumin (HSA), the study of the binding between the two has great significance on human health. In this paper, we systematically investigated the binding of SB and BSA under the simulated physiological conditions combining with various common analytical methods, e.g., fluorescence, UV–vis absorption, synchronous fluorescence and circular dichroism (CD) spectra, as well as molecular docking method. The fluorescence quenching measurements were respectively carried out at 298 K, 303 K and 308 K using the Stern–Volmer method. The results reveal that ground state SB–BSA complex was formed within the binding constants from 2.02 × 104 to 7.9 × 103 M−1. Meanwhile, the negative values of ΔH0 (− 43.92 kJ mol−1) and ΔS0 (− 111.6 J mol−1 K−1) demonstrated that both the hydrogen binding interaction and van der Waals forces contributed to stabilizing the SB–BSA complex. The site marker competitive experiments show that the SB and BSA bound at site I. Furthermore, the experimental results of UV–vis absorption, synchronous fluorescence and CD spectra indicate that the binding of SB and BSA may change the conformation of BSA. In addition, the molecular docking experiment suggests that hydrogen bond was formed in the interaction between SB and BSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a recognized food-grade preservative, sodium benzoate (SB), whose structure is shown in Fig. 1, is widely used in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries [1,2,3]. For example, in the food industry, SB is used in a variety of foods and beverages, such as salads, kimchi, carbonated beverages, jams, juices, and soy sauce, due to its effective inhibition of fungal and bacterial growth during storage [2, 4]. In addition, SB is also applicable in clinically practice and can to treat various diseases, such as urea cycle disorders, liver disease, multiple sclerosis, and early Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease [5, 6]. Although SB as a preservative is generally recognized as safe (GRAS), its concentration is limited to 0.1% by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [7]. In recent years, studies have shown that the organic form of SB is nontoxic, but its synthetic form is toxic to organisms at chronic doses [8]. Furthermore, it has been reported that SB may damage mitochondrial DNA [9]. Nevertheless, the results of these investigations remain controversial. The interaction between SB and biomacromolecules requires a more in-depth research.

The effect of SB on health can be explored by studying the interaction between SB and Serum albumin (SA). SA, the most abundant translocator protein in blood circulation [10, 11], has several critical physiological functions, for example, the maintenance of the colloidal osmotic blood pressure, and the transportation of various endogenous and exogenous compounds [12, 13]. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is not only widely used in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, but also widely utilized as a ligand-biological model to study the interactions between small molecules and globular proteins, due to its high stability, low-cost, versatile ligand-binding properties, medical importance and high structural homology with human serum albumin (HSA) (approximately 76%) [14, 15]. BSA is a single-chain globular protein consisting of 583 amino acid residues, forming 17 disulfide bonds [16]. In addition, BSA contains two major specific ligand-binding sites located in the hydrophobic cavities in sub-domains II-A and III-A, which are also known as Sudlow’s site I and Sudlow’s site II, respectively [17]. Meanwhile, previous works have demonstrated that the durability and toxicity of chemicals have huge influence on the structure of BSA because of interaction effect [18]. Moreover, several studies have shown that secondary structure of BSA changes upon binding with small molecules [19,20,21]. Therefore, investigating the interaction between BSA and chemicals, especially small molecules is of great significance.

In this work, the interaction between SB and BSA was studied by employing multi-spectroscopic methods and molecular docking (MD) modeling. Fluorescence spectroscopy was first used for understand the binding mechanism, and quenching mechanism, binding constant, mode and site were analyzed. Then, UV–vis absorption, synchronous fluorescence and CD spectra were employed to determine the conformation and structure of BSA when SB was binding. Furthermore, to further interpret the experimental findings, molecular docking modeling was used to explore the molecular graph of the binding interaction.

Experimental

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals used in this experiment, including BSA (lyophilized powder, Mw ≈ 66.2 kDa, Sigma) and sodium benzoate (Sinopharm), are of high purity. Thus, no further purification is required after purchase. PBS buffer solution (20 mM, pH = 7.40) was prepared with the ultrapure water (ρ = 18.2 MΩ cm). Then, BSA solution was prepared using PBS as a solvent for the spectral experiments. Additionally, all solutions were stored in the dark environment with a low temperature of 4 °C before using.

Measurements of the fluorescence spectra

Fluorescence experiments were taken out with the RF-5301 (Shimadzu, Japan) fluorescence spectrophotometer. Firstly, BSA solution (1 × 10−6 M) was added to a quartz cell with size of 1.0 cm. An equal amount of BSA was added to the reference solution to eliminate the absorbance of BSA itself, and the absorbance of PBS buffer was subtracted through base line correction. Then, SB of different concentrations from 0 to 8 × 10−6 M was gradually dropped into the BSA using a microsyringe. The transportation of various molecules and materials in the blood circulatory system are regulated by albumin. Some of the small molecules entered into the blood are reversibly bound to plasma proteins, forming binding molecules. While those do not bind are free molecules. When the concentration of free molecules decreases, some of the binding molecules dissociate into free molecules, thus, they are always in dynamic equilibrium [22]. In our experiment, SB and BSA were let stand for 5 min to reach dynamic equilibrium [23]. During the fluorescence measurement, the slit width was set at 10 nm/10 nm, the excitation wavelength was 285 nm, and the scanning range of the fluorescence emission spectrum was 300–450 nm.

Measurements of the synchronous fluorescence

The synchronous fluorescence of SB–BSA was measured using the same concentrations of the mixture solutions as in the fluorescence quenching measurements, but at room temperature. Spectra were recorded at Δλ = 15 nm and 60 nm, which showed the tyrosine residue and tryptophan residue characteristics of the BSA.

Measurements of UV–vis spectra

The UV–vis absorption spectra were obtained by a UV-3600 (Shimadzu, Japan) spectrophotometer. The concentration of BSA was kept at 1 × 10−6 M, while the concentration of the added SB ranged from 0 to 8 × 10−6 M, each time with an increase of 2 × 10−6 M. The absorption spectra of the BSA between 230 and 330 nm were recorded in a 1 cm quartz absorption cell.

Measurements of CD spectra

CD spectra were recorded using the spectropolarimeter of JASCO J-810 and a 1.0 cm quartz absorption cell. Note that the spectrum of a cell only with PBS buffer solution was firstly measured as background signal to remove the influence of PBS buffer solution.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking simulation was employed to study the molecular interaction between BSA and SB using Auto Dock Vina, an open-source software with significantly fast dock running speed and high molecular docking accuracy [24]. To prepare the protein and ligand molecules for docking study, BSA crystal structure was first retrieved from the Protein Data Band (PDB ID: 3V03) (http://www.rcsb.org/structure/3V03), and then loaded on AutoDock Tools to remove additional molecules, e.g., all the water molecules. Next, Polar hydrogens and Gasteiger charges were added, respectively. The structure of SB was prepared by drawing the 2D chemical structure using ChemOffice and further optimized based on MM2 force field implemented using Chem3D. After that, the structurally optimized BSA and SB were employed to conduct molecular docking simulation. During the simulation, the size of the grid box along x-, y- and z-directions were all set at 18 Å and the grid spacing 1 Å. The grid box center was set at (88.537, 24.797, 13.111). The energy range and values were set at 4 kcal/mol and 100, respectively.

Results and discussion

Fluorescence spectral analysis of the interactions involving SB with BSA

Fluorescence quenching of BSA

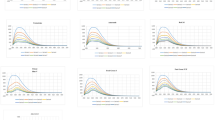

Tryptophan (Trp), tyrosine (Tyr) and phenylalanine (Phe) residues are three main amino acids that can make protein generate endogenous fluorescence [25]. The major contribution to the changed fluorescence of BSA is from the environmentally-sensitive tryptophan (Trp) moiety [26]. The fluorescence emission spectra of BSA with various concentration of SB are shown in Fig. 2a. When excited at 285 nm, BSA had a characteristic band at around 344 nm. Furthermore, when the concentration of the added SB increased from 0 to 8 × 10−6 M, the fluorescence intensity of BSA decreased significantly, indicating that the environment around the Trp residues of BSA varied with the addition of SB. Therefore, it can be inferred that there is a binding interaction between SB and BSA, and the binding site is located near the Trp residue [27].

Fluorescence spectra of BSA solution (1 × 10−6 M) in the absence and presence of different concentrations of SB (T = 298 K, pH = 7.40, λ ex = 285 nm). a From a to i, the SB concentration increased from 0 to 8.0 × 10−6 M, with a step size of 1.0 × 10−6 M. b Quenching effect of Stern–Volmer on BSA induced by SB

The reaction temperatures for SB–BSA system were maintained at 298 K, 303 K, and 308 K, respectively. The fluorescence quenching data are analyzed by the Stern–Volmer equation [28]:

where F and F0 are the fluorescence intensity of BSA with and without the quencher, i.e., SB, respectively. KSV is the Stern–Volmer quenching constant with the unit being M−1, and [Q] is the concentration of the quencher. kq is the quenching rate constant of BSA. τ0 is the average fluorescence lifetime of BSA in the excited state without the quencher (the order of magnitude is 10−8) [28]. KSV and Kq value of BSA triggered by SB at different temperatures can be determined by calculating the slope of the curve, as shown in Fig. 2b. The values of the parameters KSV, kq and R at different temperatures are listed in Table 1. It can be seen from the results that KSV decreases from 1.87 × 104 to 1.34 × 104 M−1 as the temperature increases from 298 to 308 K. Moreover, the values of kq at various temperatures are all in the order of 1012 M−1 s−1, which are much larger than the maximum diffusion collision quenching rate constant (2.0 × 1010 M−1 s−1), indicating that the SB-trigger BSA quenching process is static rather than dynamic.

Interaction parameters and binding model for SB–BSA complex

The binding constants (Kb) and binding site (n) of SB–BSA complex is calculated using the following formula [29]:

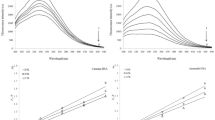

According to the Eq. (2), Kb and n can be calculated from the curve of log[(F0−F)/F] versus log[Q], as shown in Fig. 3a. The calculated results are summarized in Table 2. These results show that within the temperature range studied, the value n of SB–BSA complex is close to 1, indicating that BSA has a single high affinity binding site for SB. Kb is calculated to be approximately 104, indicating strong binding interactions between SB and BSA. It is also found that as temperature increases, Kb value decreases, suggesting that the stability of SB–BSA complex decreases with the increasing of temperature.

To better understand the binding between BSA and SB, the van’t Hoff Eq. (3) was used to calculate the thermodynamic enthalpy (H0) and entropy (S0) of BSA and SB complexation.

As shown in Fig. 3b, the curves of lnKb and 1/T were used to determine the thermodynamic parameters of SB–BSA complex at three different temperatures, i.e. 298 K, 303 K, and 308 K. Once the H0 and S0 values are determined, the variation in Gibbs free energy (G0) can be calculated by the following standard Eq. (4).

Here, the binding constant values at three different temperatures, i.e. ΔG0, ΔH0 and ΔS0, are listed in Table 2. The negative value of ΔG0 indicates that the interaction process between SB and BSA is spontaneous. And the positive H0 and S0 values indicate that hydrogen bonding and van der Waals interactions play a major role in the binding of the chemical to the protein [30, 31].

Combination of fluorescent probes

To determine the displacement percentage of the fluorescent combination probe, according to the method introduced by Sudlow et al., the fluorescence markers for distinct binding sites were chosen: ketoprofen for site I and ibuprofen for site II [32]. And the following equation is also adopted.

where F1 and F2 represent the fluorescence intensity of the SB–BSA system in the absence and presence of the probe, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4. The increase in ketoprofen concentration results in significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the SB–BSA system. However, the increase in ibuprofen concentration has little impact on the fluorescence intensity of BSA. Therefore, SB and BSA are supposed to bind at site I [33].

Conformational change of BSA

Analysis of the UV–visible absorption spectra

UV absorption measurement, a very simple and effective method, is often used to observe the formation process and the change in the conformation of protein during the its binding interaction between with small molecule. The UV spectra of SB–BSA complex are shown in Fig. 5. All SB–BSA complex have absorption bands. The absorption band around 280 nm is the result of the π–π* transition of aromatic amino acids (Trp, Tyr, and Phe) [34]. Adding SB (0–8.0 × 10−6 M) to the BSA solution enhances the absorption intensity (0.044–0.0556), and the maximum wavelength shows a slight blue shift at around 280 nm. The UV absorption intensity increases with the increase of SB concentration, indicating that complex is formed by SB and the amino acid residues of BSA.

Synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy

The synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy is a useful tool for obtaining information around chromophore microenvironment. Usually, the shift of the λem represents the alteration of the polarity of the amino acid environment (particularly Tyr or Trp residues) [35]. The synchronous fluorescence spectra were carried out for investigating structural change in BSA with SB addition (Fig. 6). The fluorescence spectra characteristic of tyrosine and tryptophan residues are shown in Fig. 6a (Δλ = 15 nm) and Fig. 6b (Δλ = 60 nm), respectively [36]. It is obvious that the fluorescence intensity of the tryptophan residues are much stronger than that of tyrosine residues in Fig. 6. And no significant change is found in the fluorescent emission peak position of both tyrosine and tryptophan residues. Thus, the addition of SB did not rearrange the microenvironment of the tyrosine and tryptophan residues in BSA.

Analysis of CD spectra

To further explore whether SB can induce conformational change in BSA, CD spectroscopy experiments were performed. The two negative bands at 208 nm (π–π* transition) and 222 nm (n-π* transition) in CD spectrum of free BSA are characteristic of the protein α-helical structure [37], whose content can be estimated by [38]:

where MRE208 is the MRE value observed at 208 nm, 4000 is the MRE value of the β shape and random coil conformation at 208 nm, and 33000 is the MRE value of the pure α-helix at 208 nm. The MRE208 value used to indicate the change in secondary structure of BSA determined by [38]:

where n is the number of amino acid residues (583 for BSA). l is the cell path length, and Cp is the molar concentration of BSA. When SB:BSA ratio increases from 0 to 2:1, the band intensities of the CD spectra have a slight decrease, whereas the peaks positions remain unchanged, as shown in Fig. 7. The results demonstrate that the secondary structure of BSA has a partial change from α-helical content. The α-helical content decreased from 62.7% of free BSA to 61.88% (SB:BSA = 1:1) and 60.24% (SB:BSA = 2:1). Based on these analyses, we conclude that the addition of SB alters the secondary structure of BSA, resulting in a decrease in α-helical content, which is nonetheless still dominant in the secondary structure.

Molecular docking

To further elucidate SB–BSA binding interaction, molecular docking was used to simulate the molecular interaction between BSA and SB. The simulated result of the predominate configuration of SB–BSA complex is plotted in Fig. 8, where the binding energy is the lowest. Moreover, as shown in Fig. 9, the binding results indicate that SB is very close to the amino acid residues Tyr149, Leu237, Arg256, Leu259, Ala260, Ile263, Ser286, Ile289, and Ala290 at site I in subdomain IIA. The hydrogen bonding between SB and BSA (Tyr149, ARG256 with a bond length of 3.0 Å, 2.2 Å and 2.0 Å) is also responsible for maintaining the stability of the complex. Here, note that the calculated combined Gibbs free energy is − 5.7 kcal/mol (− 23.8 kJ/mol) and binding constant (Kb) is about 1.45 × 104 mol/L, which is quite different with our experimental result (ΔG = − 935 kJ/mol and Kb = 2.2 × 104 mol/L). This may be caused by the difference between X-ray crystal structure of BSA and its solution state in the aqueous system.

Conclusion

In this study, we combined the multi-spectroscopic methods and molecular docking modeling to systematically investigate the interaction between SB and BSA. The multi-spectroscopic data show that the quenching of BSA binding with SB was caused by the formation of SB–BSA complex. The negative values of ΔH0 and ΔS0 demonstrated that hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces contribute to make the SB–BSA complex stable. The negative values of ΔG indicate that the interaction process was spontaneous. Site marker competitive experiments show that SB and BSA bound at site I. In addition, the amino acid microenvironments and the secondary structure of BSA were altered by the addition of SB, as shown in UV–vis absorption, synchronous fluorescence spectroscopy and CD spectra data. Furthermore, molecular docking studies provided some valuable information on the interaction between SB and BSA and structural stability of their complex.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material analyzed or generated during this investigation are included in this published article. The raw data can be requested from email of JY: 95634941@qq.com.

Abbreviations

- SB:

-

sodium benzoate

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- HSA:

-

human serum albumin

- CD:

-

circular dichroism

- GRAS:

-

generally recognized as safe

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- SA:

-

serum albumin

- MD:

-

molecular docking

References

Baranowska I, Wojciechowska I, Solarz N et al (2013) Determination of preservatives in cosmetics, cleaning agents and pharmaceuticals using fast liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr Sci 52(1):88–94

Lennerz B-S, Vafai S-B, Delaney N-F, Clish A-B, Deik A-A, Pierce K-A, Ludwig D-S, Mootha V-K (2015) Effect of sodium benzoate, a widely used food preservative, on glucose homeostasis and metabolic profiles in humans. Mol Genet Metab 114(1):73–79

Ikarashi Y, Uchino T, Nishimura T (2010) Analysis of preservatives used in cosmetic products: salicylic acid, sodium benzoate, sodium dehydroacetate, potassium sorbate, phenoxyethanol, and parabens. Bull Natl Inst Health Sci 128:85–90

Nettis E, Colanardi M-C, Ferrannini A et al (2004) Sodium benzoate-induced repeated episodes of acute urticaria/angio-oedema: randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 151(4):898–902

Yavav A, Kumar A, Das M, Tripathi A (2016) Sodium benzoate, a food preservative, affects the functional and activation status of splenocytes at non cytotoxic dose. Food Chem Toxicol 88:40–47

Häberle J, Boddaert N, Burlina A, Chakrapani A, Dixon M, Huemer M, Karall D, Martinelli D, Crespo P-S, Santer R, Servais A, Valayannopoulos V, Lindner M, Rubio V, Dionisi-Vici C (2012) Suggested guidelines for the diagnosis and management of urea cycle disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis 7(1):32

Misel M-L, Gish R-G, Patton H, Mendler M, Pahan K (2011) Immunomodulation of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by cinnamon metabolite sodium benzoate. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 33(4):586–593

Kehinde O-S, Christianah O-I, Oyetunji O-A (2018) Ascorbic acid and sodium benzoate synergistically aggravates testicular dysfunction in adult Wistar rats. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 10(1):39

Piper J-D, Piper P-W (2017) Benzoate and sorbate salts: a systematic review of the potential hazards of these invaluable preservatives and the expanding spectrum of clinical uses for sodium benzoate. Compr Rev Food Sci F 16(5):868–880

Zhang Q, Ni Y, Kokot S (2016) Competitive interactions between glucose and lactose with BSA: which sugar is better for children? Analyst 141(7):2218–2227

Leblanc A, Shiao T-C, Roy R, Sleno L (2014) Absolute quantitation of NAPQI-modified rat serum albumin by LC-MS/MS: monitoring acetaminophen covalent binding in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol 27(9):1632–1639

Sharifi M, Dolatabadi JEN, Fathi F et al (2017) Kinetic and thermodynamic study of bovine serum albumin interaction with rifampicin using surface plasmon resonance and molecular docking methods. J Biomed Opt 22(3):037002

Janek T, Czyżnikowska Ż, Łuczyński J et al (2017) Physicochemical study of biomolecular interactions between lysosomotropic surfactants and bovine serum albumin. Colloids Surf B 159:750–758

Mote U-S, Bhattar S-L, Patil S-R (2010) Interaction between felodipine and bovine serum albumin: fluorescence quenching study. J Lumin 25(1):1–8

Shama Y, Riyazuddeen (2017) Exploring thermodynamic parameters and the binding energetic of berberine chloride to bovine serum albumin (BSA): spectroscopy, isothermal titration calorimetry and molecular docking techniques. Thermochim Acta 655:76–78

Chaturvedi S-K, Ahmad E, Khan J-M, Alam P, Ishtikhar M, Khan R-H (2015) Elucidating the interaction of limonene with bovine serum albumin: a multi-technique approach. Mol Bio Syst 11(1):307–316

Guan J, Yan X, Zhao Y-J, Sun Y-H, Peng X (2018) Binding studies of triclocarban with bovine serum albumin: insights from multi-spectroscopy and molecular modeling methods. Spectrochim Acta A 202:1–12

Shi JH, Zhou KL, Lou YY, Pan DQ (2018) Multi-spectroscopic and molecular modeling approaches to elucidate the binding interaction between bovine serum albumin and darunavir, a HIV protease inhibitor. Spectrochim Acta A 188:362–371

Skrt M, Benedik E, Podlipnik C, Poklar Ulrih N (2012) Interactions of different polyphenols with bovine serum albumin using fluorescence quenching and molecular docking. Food Chem 135(4):2418–2424

Tian J, Liu J, He W, Hu Z, Yao X, Chen X (2004) Probing the binding of scutellarin to human serum albumin by circular dichroism, fluorescence spectroscopy, FTIR, and molecular modeling method. Biomacromol 5(5):1956–1961

Makarska-Bialokoz M (2017) Investigation of the binding affinity in vitamin B12-Bovine serum albumin system using various spectroscopic methods. Spectrochim Acta A 184:262–269

Agarwal R-P, Phillips M, McPherson R-A et al (1986) Serum albumin and the metabolism of disulfiram. Biochem Pharmacol 35(19):3341–3347

Zhang J, Li WX, Ao BY et al (2014) Fluorescence enhancement of europium (III) perchlorate by benzoic acid on bis (benzylsulfinyl) methane complex and its binding characteristics with the bovine serum albumin (BSA). Spectrochim Acta A 118:972–980

Trott O, Olson A-J (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31(2):455–461

Lou Y-Y, Zhou K-L, Pan D-Q et al (2017) Spectroscopic and molecular docking approaches for investigating conformation and binding characteristics of clonazepam with bovine serum albumin (BSA). J Photochem Photobiol B 167:158–167

Sandhya B, Hegde A-H, Kalanur S-S et al (2011) Interaction of triprolidine hydrochloride with serum albumins: thermodynamic and binding characteristics, and influence of site probes. J Pharm Biomed Anal 54(5):1180–1186

Shen G-F, Liu T-T, Wang Q, Jiang M, Shi J-H (2015) Spectroscopic and molecular docking studies of binding interaction of gefitinib, lapatinib and sunitinib with bovine serum albumin (BSA). J Photochem Photobiol B 153:380–390

Zhao L-Z, Liu R-T, Zhao X-C, Yang B-J, Gao C-Z, Hao X-P et al (2009) New strategy for the evaluation of CdTe quantum dot toxicity targeted to bovine serum albumin. Sci Total Environ 407(18):5019–5023

Safarnejad A, Shaghaghi M, Dehghan G, Soltani S (2016) Binding of carvedilol to serum albumins investigated by multi-spectroscopic and molecular modeling methods. J Lumin 176:149–158

Ross P-D, Subramanian S (1981) Thermodynamics of protein association reactions: forces contributing to stability. Biochemistry 20(11):3096–3102

Xu X-Y, Du Z-Y, Wu W-H, Wang Y-F, Zhang B, Mao X-Y, Jiang L, Yang J, Hou S-F (2017) Synthesis of triangular silver nanoprisms and spectroscopic analysis on the interaction with bovine serum albumin. Anal Bioanal Chem 409(22):5327–5336

Yao D, Yu J, Pan Y-M, Huang F-P, Bian H-D, Yu Q, Liang H, Chen Z-F (2012) Spectroscopic studies on the binding of kaempferol-3,7-α-l-rhamnopyranoside to bovine serum albumin. Chin J Chem 30(2):438–444

Zhang G-W, Ma Y-D (2013) Mechanistic and conformational studies on the interaction of food dye amaranth with human serum albumin by multispectroscopic methods. Food Chem 136(2):442–449

Chi Z-X, Liu R-T, Teng Y, Fang X-Y, Gao C-Z (2010) Binding of oxytetracycline to bovine serum albumin: spectroscopic and molecular modeling investigations. J Agric Food Chem 58(18):10262–10269

Ghosh K, Rathi S, Arora D (2016) Fluorescence spectral studies on interaction of fluorescent probes with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). J Lumin 175:135–140

Abert W-C, Gregory W-M, Allan G-S (1993) The binding interaction of Coomassie blue with proteins. Anal Biochem 213(2):407–413

Yasmeen S, Riyazuddeen (2017) Biophysical insight into the binding of triprolidine hydrochloride to human serum albumin: calorimetric, spectroscopy and molecular docking approaches. J Mol Liq 233:55–63

Shi J-H, Chen J, Wang J, Zhu Y-Y, Wang Q (2015) Binding interaction of sorafenib with bovine serum albumin: spectroscopic methodologies and molecular docking. Spectrochim Acta A 149:630–637

Acknowledgements

All authors would like to thank School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen university for his support and providing the possible facilities for completing this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 11474363, 11672339), Guangdong Natural Science Funds (No. 2015A030313082), Guangzhou science and technology key project (No. 201707020002). All funding bodies played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Experiments was accomplished by JY and WX. The molecular docking study was accomplished by JL. JY and XZ accomplished the writing of the article. XZ and YZ were the study designers and corresponding authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, J., Liu, JY., Xiong, WM. et al. Binding interaction of sodium benzoate food additive with bovine serum albumin: multi-spectroscopy and molecular docking studies. BMC Chemistry 13, 95 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-019-0615-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13065-019-0615-6