Abstract

Background

This study evaluates a novel bronchodilator, S1226, for its efficacy in reversing allergen-induced bronchoconstriction in subjects with mild, allergic asthma. S1226 is a new class of bronchodilator that is an aerosol/vapor/gas mixture combining pharmacological and biophysical principles for a novel mode of action. It contains a potent bronchodilator gas (carbon dioxide or CO2) and nebulized perflubron (a synthetic surfactant possessing mucolytic properties). It has demonstrated rapid reversal of allergen-induced bronchoconstriction in an ovine study model.

Methods

This was a phase IIa proof-of-concept, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, crossover single-dose clinical trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of S1226 (8% CO2) administered by nebulization following an allergen-induced early asthmatic response in 12 subjects with mild, allergic asthma. Primary safety endpoints were adverse events, vital signs, pulse oximetry, and spirometry. Efficacy endpoints included bronchodilator response (measured as the forced expiratory volume in 1 s or FEV1) over time, the area under the curve of FEV1 for the early asthmatic response over time, and achievement of responder status, defined as a 12% improvement after the allergen challenge.

Results

No significant safety issues were observed. All adverse events were non-serious, mild, and transient. There was a statistically significant decrease in peripheral blood oxygenation levels over time in the placebo group following allergen inhalation, whereas blood oxygenation was maintained at normal levels in the S1226-treated subjects (P = 0.028). This effect was greatest 5 min after start of treatment (P < 0.001). The recovery rate was faster but not significantly so (P = 0.272) for S1226 compared to the placebo at earlier time points (5, 10, and 15 min), as assessed by ≥12% reversal of FEV1. The recovery of FEV1 over time was significantly greater (P = 0.04) with S1226 compared to the placebo.

Conclusions

S1226 was safe, tolerated well, and provided bronchodilation and improved blood oxygenation in subjects with mild atopic asthma following allergen-induced bronchoconstriction. Additional studies to optimize the therapeutic response are indicated.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02334553. Registered on 12 November 2014.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inhaled bronchodilators, including short-acting beta-2-adrenergic agonists and anticholinergics along with anti-inflammatory medications, are first-line treatments for emergency management of acute asthma exacerbations [1, 2]. Effective bronchodilation is a challenge during exacerbations and having an additional class of bronchodilator in the treatment arsenal would be beneficial.

Existing bronchodilator treatments are effective in most cases, but there are several reasons why they can fail during exacerbations. First, in severe exacerbations, particulate medications may be unable to penetrate airways obstructed by bronchoconstriction, mucus plugs, and inflammation. Second, patients become less responsive to traditional bronchodilators from chronic use, due to tachyphylaxis and tolerance [3,4,5]. Third, there is a group of patients with asthma refractory to standard therapies [6] and these patients represent an unmet clinical need for whom alternative treatment options are required. The challenge is to find an alternative treatment to augment conventional therapy.

This study evaluates a new class of bronchodilator, S1226, which combines pharmacological and biophysical properties. S1226 is an aerosol/vapor/gas mixture containing a bronchodilator gas (CO2) and a nebulized synthetic surfactant (perflubron) that has mucolytic [7, 8] and anti-inflammatory properties [9,10,11]. Previous studies have shown that inhalation of 6% CO2 over 4–5 min in atopic asthmatics relieved exercise-induced asthma. However, its effects were short-lived [12]. The bronchodilatory effects of CO2 are complex. They involve pH and epithelial-dependent mechanisms [13] and do not require adrenergic [14] or cholinergic pathways [12]. The combination of CO2 with perflubron in preclinical studies produced a synergistic effect, providing rapid and sustained bronchodilation [13,14,15]. S1226 showed rapid opening of airways in sheep sensitized and challenged with house dust mites and rats sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin. The effect was fast (<4 s for bronchodilation) and sustained (>20 min) [15].

A phase I clinical trial was completed in 36 healthy volunteers to assess safety and tolerability of S1226. All adverse events (AEs) were mild and transient and S1226 appeared safe at CO2 concentrations of 4%, 8%, and 12% [16].

We now undertook a phase IIa, proof-of-concept, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, crossover single-dose study to demonstrate safety, tolerability, and efficacy of nebulized S1226 (8% CO2) in subjects with mild, atopic asthma. We chose 8% CO2 in this first study in asthmatic humans as this level of CO2 was effective in animal studies and had no AEs in the phase I clinical trial [16]. An abstract of the study described in this paper was presented as a poster at the American Thoracic Society meeting in 2016 [17].

Methods

Participants

Adult volunteers, aged 18–40 years, with mild, allergic asthma were screened to confirm the presence of an early asthmatic response (EAR) to inhaled allergen. PC20 methacholine indicates a provocative concentration of inhaled methacholine producing a 20% reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1). All subjects had had asthma for more than 3 months, and their inclusion was based on a PC20 methacholine of ≤16 mg/mL and an allergen-induced EAR producing a ≥20% reduction in FEV1 during screening. The full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Additional file 1.

Trial design

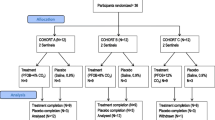

This was a phase IIa, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study enrolling 12 subjects with asthma. The study design is outlined in Fig. 1.

The study consisted of a <30-day screening period, two treatment periods with a minimum 2-week washout in between, and a follow-up visit 1 day later. A detailed schedule of assessments during the clinical trial study are shown in Additional file 2. Baseline screening involved routine chemistry, hematology, urinalysis, methacholine inhalation testing (PC20 ≤ 16 mg/mL), and allergen skin prick tests. An allergen inhalation challenge to common aero-allergens (cat, horse, and grass pollen) was used to establish the allergen concentration required to achieve a 20% fall in FEV1 as previously reported [5, 18]. This concentration was used in the subsequent treatment periods with the goal of achieving comparable EARs (20% fall in FEV1) between the two treatment periods. The allergen challenge model has excellent within-subject repeatability and hence, in crossover studies, a sample size of 12 subjects is sufficient to detect an effect on clinically relevant outcome measures with a power of 90% [18].

For this study, a sample size of 16 subjects was estimated to be able to detect a treatment difference of at least a 14% change in FEV1 with a 95% confidence interval with a power of over 90% in a two-sided test, assuming that the variability observed would be like the response to S1226 in the sheep allergen challenge model [15]. The sheep model used airway resistance as a model of airway caliber. Under similar assumptions, a sample size of 12 subjects was estimated to able to detect a treatment difference of at least 17% change in FEV1 with a 95% confidence interval and a power of 90%.

In summary, in this proof-of-concept study, using the animal data and taking the robustness of this model into consideration, our goal was to recruit up to 16 subjects with the expectation of retaining at least 12 subjects to account for any dropouts.

The test procedures were conducted at least 6 weeks after any relevant seasonal allergen exposure and the study lasted approximately 9 weeks for each subject.

Each treatment period consisted of a methacholine challenge on day 1 to confirm airway hyperresponsiveness (methacholine PC20 within 1 doubling concentration of baseline PC20), an allergen challenge followed by study intervention (S1226 or placebo) on day 2, and spirometry on day 3 to confirm recovery from allergen inhalation. Immediately after a 20% fall in FEV1 was documented as part of the EAR, a single dose of S1226 (8%) or placebo was administered via nebulization to subjects over 2 min with a Circulaire ® II hybrid nebulizer system (Westmed, Tucson, AZ, USA). Subjects were allowed to stop receiving the interventions at any time.

S1226 (8%) (SolAeroMed, Calgary, AB, Canada) consists of 3 mL of perflubron nebulized with medical grade compressed gas (Praxair Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada) containing 8% CO2, 21% O2, and balanced N2 at a flow rate of 9 L/min. The placebo was 3 mL saline (0.9% NaCl) (Smiths Medical ASD Inc. Markham, ON, Canada) with medical grade air (Praxair Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada) at a flow rate of 9 L/min. The Circulaire nebulizer system incorporates an inflatable reservoir bag, which collects nebulized gas during exhalation so that during inhalation the subject receives both freshly generated nebulized drug and stored nebulized drug.

The study was double-blind. The treatments were prepared and administered by an unblinded research associate, who performed no other procedures in the study. Personnel conducting testing procedures and collecting study outcomes were blinded to the treatment allocation. Although S1226 (8%) and placebo have different viscosities and densities [16], they had identical visual appearances and the same model of nebulizer was used to administer both compounds. Thereby, the identity of the treatments remained blinded to the study subjects.

The treatment order of placebo and S1226 (8%) for each subject was randomized in a 1:1 ratio in blocks of four, using a computer-generated randomization list. Both study subjects and the clinical personnel involved in collection and monitoring of study data and evaluation of AEs were blinded with respect to the subject’s treatment allocation.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the standard operating procedures for the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre. Calgary Lab Services completed the clinical laboratory work. The project was monitored by and the statistical analysis was completed by JSS Medical Research Inc., St Laurent, QC, Canada.

The study was conducted at the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre, University of Calgary, AB, Canada, from January 2015 to April 2016, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2014). The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary approved the study protocol, amendments, and consent form (REB14–1581). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was safety; efficacy was a secondary outcome measure. The incidence of treatment-emergent AEs was monitored, recorded, and graded for severity and assigned attribution.

The safety and tolerability of S1226 (8%) was evaluated based on the following assessments:

-

The number and proportion of subjects experiencing treatment-emergent AEs

-

12-lead electrocardiogram at screening and follow-up

-

Vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) at screening, pre-dose, and at 120 min post-dose

-

Pulse oximetry at screening, pre-dose, and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min post-dose and follow-up

-

Safety biochemistry, hematology, and urinalysis at screening and follow-up

-

FEV1 was measured pre-dose and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min post-dose, while spirometry (FEV1 and forced vital capacity) was conducted at screening and follow-up

The efficacy of S1226 (8%) was evaluated based on the following endpoints:

-

Area under curve (AUC) of recovery from the EAR in the first 30 and 90 min following treatment

-

Responder status, defined as achieving ≥12% improvement in FEV1 after the allergen challenge

-

Time to achieve responder status

-

Maximum percentage reversal of allergen-induced decrease in FEV1 in the first 30 and 90 min following study treatment administration

Statistical methods

The total number of AEs was summarized for each treatment group by seriousness, intensity, relationship to product, and outcome. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA version 18.1) and summarized using the total number of AEs, total number and percentage of subjects who experienced an AE, and number and percentage of subjects who experienced an AE within each preferred term. No inferential statistical analysis of safety data was performed.

The AUC of the EAR reversal following study drug inhalation was calculated using the trapezoidal rule. The AUCs within 30 min and 90 min from study drug inhalation were compared between S1226 (8%) and the placebo using a mixed general linear model. The model included subject as a random effect; treatment group, period, and sequence as fixed effects; and FEV1 at study drug inhalation as a covariate. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) mixed model was used to compare the FEV1 and AUC over time between S1226 (8%) and placebo. Like the primary analysis, the model included subject as a random effect; treatment group, period, and sequence as fixed effects; and FEV1 at study drug inhalation as a covariate.

Achievement of responder status, defined as ≥12% reversal of FEV1 from study drug inhalation within 30 and 90 min, was compared between S1226 (8%) and the placebo using logistic regression where period and FEV1 at study drug inhalation were entered as terms. Time to achieve responder status was compared between treatment groups using a Cox regression. The model considered treatment group, period, and FEV1 at study drug inhalation as covariates. In addition, randomization order was included as a covariate in the mixed models of AUC30, AUC90, FEV1, and AUC over time to evaluate a carryover effect that would favor one treatment vs the other.

Results

A total of 14 subjects were screened, of whom 12 were eligible and received both interventions. One subject missed the final follow-up visit but their assessments for the two intervention treatments were included in the results.

Patient characteristics at baseline, including demographic and clinical measurements, are summarized in Table 1. The mean (standard deviation, SD) age at baseline for the total cohort was 27.3 (2.4) years. Exactly half of the subjects were female and Caucasian; Asians accounted for 25.0% of subjects. Mean (SD) height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were 1.7 (0.1) m, 68.5 (17.9) kg, and 23.8 (4.5) kg/m2, respectively.

Safety and tolerability

During the study, 17 AEs were reported, all of which were judged to be mild in severity and transient. Of the 17 AEs, 10 were not related to the investigational products. The majority of these (n = 8) were related to the nebulizer device. Two AEs were possibly related to the placebo and five AEs were probably related to S1226. AEs associated with S1226 were palpitations (1), chest discomfort (1), dizziness (2), and anxiety (1), while feeling hot (1) and flushing (1) were associated with the placebo. Details of the AEs by severity, relation to drug, outcome, and preferred terms are given in Additional files 3 and 4.

No abnormalities in the electrocardiogram, vital signs (respiratory rate and blood pressure), and biochemistry variables were associated with S1226 or the placebo at screening, pre-dose, or 120 min post-dose.

When using a mixed model that adjusted for treatment period, sequence, and pre-dose percentage oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (%SpO2), the absolute change between pre-dose and post-dose %SpO2 was significantly different (P = 0.028) for the S1226 group compared with the placebo group over time (Fig. 2). Least squares estimates showed that the S1226 group experienced a lower drop in %SpO2 (estimate: -0.627; P = 0.267) compared to the placebo group (estimate: -2.502; P < 0.001) 5 min post-dose. Furthermore, the placebo group showed higher absolute decreases in %SpO2 for all time points with the exceptions of the 45-min time point.

Oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry, placebo vs S1226. The absolute change between pre-dose and post-dose %SpO2 levels was significantly different (P = 0.028) for the S1226 group compared with the placebo group over time. %SpO2 significantly decreased 5 min post-treatment following the allergen challenge for the placebo *P < 0.001 but not for S1226 (P = 0.267). Error bars show standard errors. PA pre-allergen

AUC and FEV1 over time

FEV1 over time was significantly greater for S1226 compared with the placebo, with the difference becoming apparent as early as 5 min post-treatment (p = 0.043) (Fig. 3). There were no statistically significant differences for AUC, although values for FEV1 were numerically higher after S1226 for all time points. The mean (95% confidence interval, CI) adjusted difference in FEV1 AUC (0–30 min) between S1226 and the placebo was 0.406 (−6.146, 6.958; P = 0.893) while the mean (95% Cl) in FEV1 AUC (0–90 min) was 1.509 (−18.973, 21.991; P = 0.873). There were no significant carryover effects that would favor one treatment vs the other.

Achievement of responder status

The recovery rate was faster for S1226 than the placebo at earlier time points (5, 10, and 15 min) when assessing ≥12% reversal of FEV1 (Fig. 4). Time to achieving responder status within the 30-min period was not different between the two treatments (P = 0.272).

Discussion

A single dose of S1226 (8%) in subjects with mild, allergic asthma was safe and tolerated well and produced moderate bronchodilation following allergen-induced bronchoconstriction. Both components of S1226 (perflubron and CO2 ) have undergone extensive clinical testing and their safety profiles are well documented [9, 19, 20]. Subjects receiving S1226 reported more AEs than those receiving the placebo, but these were mild in severity, they were transient, and the majority were related to the nebulization device and not to S1226. These results are similar to those from the phase I clinical trial [16]. Based on previous research, AEs related to S1226 (dizziness, anxiety, and chest discomfort) are known transient side effects of CO2 inhalation [19, 20]. Perflubron is a stable compound used extensively in clinical applications such as bronchial lavage, liquid ventilation, and gastrointestinal contrast imaging with no known toxic effects [9].

With respect to efficacy, although the response to S1226 was numerically better compared to the placebo for all endpoints, only FEV1 over time demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in comparison to the placebo. We cautiously chose 8% CO2 (rather than 12%) as the concentration of CO2 and a treatment duration of 2 min. It is likely, based on the preclinical studies, that efficacy would be improved with the higher dose of CO2 or with an increased duration of nebulization.

S1226 was significantly more effective than the placebo at maintaining our subjects’ oxygenation saturation levels. Although the changes in oxygen saturation in our study are not clinically significant, because we necessarily studied subjects with mild and controlled asthma, the results demonstrate the potential for improving oxygenation in severe asthma exacerbations with this experimental therapy.

Six subjects experienced difficulty breathing through the nebulization device because of the volume limitation of the reservoir bag. This was not considered to be related to the drug per se. However, in the S1226 group, this difficulty may be attributed to, in part, the increased ventilatory drive caused by inhaled CO2 [20]. In future studies, ease of breathing and efficacy could be improved by using a facemask for delivery. A potential advantage of the latter is that there are CO2 receptors in the nasal passages that might augment the CO2 bronchodilator response [21].

S1226 has a unique mechanism of action, activating both pharmacological and biophysical pathways, differentiating it from traditional treatments [12,13,14]. Bronchoscopic studies in sheep have shown that S1226 dilates constricted airways within seconds, suggesting that it activates neural mechanisms, most likely through non-cholinergic, non-adrenergic nerve receptors located on and between epithelial cells in the airways [13,14,15]. Animal studies show S1226 to be equally effective for treating early and late phase asthmatic responses [14, 15, 17].

Perflubron can absorb twice its volume of CO2, thus increasing the effective dose of CO2 to the airways. This property may account for its synergistic effect when combined with CO2. Furthermore, perflubron has surfactant and mucolytic properties, which allow it to spread rapidly through airways [7, 22].

A portable rescue device is being developed for delivering S1226 that can be used in emergency home-care situations. S1226 also has potential for treating diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cystic fibrosis, for which rapid bronchodilation and mucous clearance are required. Due to its biophysical properties, it has the potential to enhance the delivery of other drugs to diseased or inflamed areas of the lung.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that S1226 is safe and effective in subjects with mild asthma and warrants further investigation in a larger patient sample. In view of S1226’s rapid effect, alternative mechanism of action, and potential to penetrate obstructed airways, it could provide additional bronchodilation when current standard-of-care rescue medication is failing.

Abbreviations

- AE:

-

Adverse event

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- EAR:

-

Early asthmatic response

- FEV1 :

-

Forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- PC20 :

-

Provocative concentration of inhaled methacholine producing a 20% reduction in FEV1

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SpO2 :

-

Oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry

References

Reddel HK, Bateman ED, Becker A, Boulet LP, Cruz AA, Drazen JM, et al. A summary of the new GINA strategy: a roadmap to asthma control. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:622–39.

Rowe BH, Sevcik W, Villa-Roel C. Management of severe acute asthma in the emergency department. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:335–41.

Cheung D, Timmers MC, Zwinderman AH, Bel EH, Dijkman JH, Sterk PJ. Long-term effects of a long-acting beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist, salmeterol, on airway hyperresponsiveness in patients with mild asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1198–203.

O’Connor BJ, Aikman SL, Barnes PJ. Tolerance to the nonbronchodilator effects of inhaled beta 2-agonists in asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1204–8.

Cockcroft DW, McParland CP, Britto SA, Swystun VA, Rutherford BC. Regular inhaled salbutamol and airway responsiveness to allergen. Lancet. 1993;342:833–7.

Wener RR, Bel EH. Severe refractory asthma: an update. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:227–35.

Al-Saiedy MR, Nelson DE, Amrein M, Leigh R, Green F. The role of an artificial surfactant in mucous plug clearance in vitro. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A5997.

Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH. Pulmonary applications of perfluorochemical liquids: ventilation and beyond. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6:117–27.

Riess JG. Understanding the fundamentals of perfluorocarbons and perfluorocarbon emulsions relevant to in vivo oxygen delivery. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol. 2005;33:47–63.

von der Hardt K, Kandler MA, Brenn G, Scheuerer K, Schoof E, Dotsch J, Rascher W. Comparison of aerosol therapy with different perfluorocarbons in surfactant-depleted animals. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1200–6.

Kandler MA, von der Hardt K, Schoof E, Dotsch J, Rascher W. Persistent improvement of gas exchange and lung mechanics by aerosolized perfluorocarbon. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:31–5.

Fisher HK, Hansen TA. Site of action of inhaled 6 per cent carbon-dioxide in lungs of asthmatic subjects before and after exercise. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:861–70.

El Mays TY, Saifeddine M, Choudhury P, Hollenberg MD, Green FH. Carbon dioxide enhances substance P-induced epithelium-dependent bronchial smooth muscle relaxation in Sprague-Dawley rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2011;89:513–20.

El Mays T, Snibson K, Wilson R, Leigh R, Dennis J, Nelson D, Green F, Choudhury P. Investigations of mechanisms of carbon dioxide-induced bronchial smooth muscle relaxation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:A2848.

El Mays TY, Choudhury P, Leigh R, Koumoundouros E, Van der Velden J, Shrestha G, Pieron CA, Dennis JH, Green FH, Snibson KJ. Nebulized perflubron and carbon dioxide rapidly dilate constricted airways in an ovine model of allergic asthma. Respir Res. 2014;15:98.

Green FH, Leigh R, Fadayomi M, Lalli G, Chiu A, Shrestha G, ElShahat SG, Nelson DE, El Mays TY, Pieron CA, Dennis JH. A phase I, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, single ascending dose-ranging study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of a novel biophysical bronchodilator (S-1226) administered by nebulization in healthy volunteers. Trials. 2016;17:361.

Green F, Leigh R, Shrestha G, Galal S, Chiu A, Fadayomi M, Pieron C, El Mays T, Nelson DE, Al-Saiedy MR, et al. Development of a new bronchodilator to enable better treatment of asthma, COPD, and CF. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:A5788.

Diamant Z, Gauvreau GM, Cockcroft DW, Boulet LP, Sterk PJ, de Jongh FH, Dahlen B, O’Byrne PM. Inhaled allergen bronchoprovocation tests. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:1045–55. e1046

Dripps RD, Comroe JH Jr. The respiratory and circulatory response of normal man to inhalation of 7.6 and 10.4 per cent CO2 with a comparison of the maximal ventilation produced by severe muscular exercise, inhalation of CO2 and maximal voluntary hyperventilation. Am J Phys. 1947;149:43–51.

Maresh CM, Armstrong LE, Kavouras SA, Allen GJ, Casa DJ, Whittlesey M, LaGasse KE. Physiological and psychological effects associated with high carbon dioxide levels in healthy men. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1997;68:41–5.

Casale TB, Romero FA, Spierings EL. Intranasal noninhaled carbon dioxide for the symptomatic treatment of seasonal allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:105–9.

Al-Saiedy M, Nelson E, El-Mays T, Amrein M, Green F. Perflubron enhances mucin plug clearance in vitro in the presence of natural surfactant. Euro Respir J. 2013;42:686.

Acknowledgements

We express appreciation to the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre at the University of Calgary for conducting the trial at their clinical facilities in Calgary, AB, Canada, and appreciate JSS Medical Research Inc., from Montreal, QC, Canada, for acting as the contract research organization in overseeing the trial and completing the data analysis. We also appreciate Sam Shrestha for formatting the final manuscript.

Funding

This clinical trial was funded by AIHS/Pfizer (grant 10004299). SolAeroMed Inc. provided the drug and placebo and funded the statistical analysis and final report by JSS. The design of the study was the responsibility of the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre, University of Calgary, AB, Canada, under the direction of Dr. Richard Leigh. Calgary Laboratory Services completed the clinical laboratory work under contract. The project was monitored by and the statistical analysis was completed by JSS Medical Research Inc., St Laurent, QC, Canada.

Availability of data and materials

Some of the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the figure files. The complete data set that supports the findings of this study are available from SolAeroMed Inc. (https://www.solaeromed.com) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, since they were used under license for the current study and are not publicly available. The data are, however, available upon reasonable request and with the permission of SolAeroMed Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS and RL designed the study protocol and take responsibility for the integrity of the data, including the interpretation of adverse effects. VS conducted the study procedures and collected the data. VS, RL, FHYG, JHD, DEN, MF, AC, SG, TYEM, and CAP were responsible for trial conception and design. JHD and CAP were responsible for drug exposure design and characterization. ER and GS acquired and analyzed the data. FHYG, VS, RL, ER, and GL, contributed to the interpretation of the data and writing of the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted at the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre, University of Calgary, AB, Canada. All procedures were conducted in accordance with the standard operating procedures for the Respiratory Clinical Trials Centre. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02334553). The study follows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 checklist (see Additional file 5).

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary approved the study protocol, amendments, and consent form (REB14–1581). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

FHYG and JHD are founders, shareholders, management, and board members of SolAeroMed Inc., a biotechnology company with patent rights for S1226. GL, MF, AC, TYEM, CAP, and RL are shareholders in SolAeroMed Inc. VS, ER, GS, SG, and DEN have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participants enrolled in the study (DOCX 18 kb)

Additional file 2:

Schedule of assessments during the clinical trial study. (DOCX 102 kb)

Additional file 3:

Adverse events (AEs) by severity, relation to drug, and outcome. (DOCX 14 kb)

Additional file 4:

Incidence of adverse events (AEs). (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 5:

CONSORT 2010 checklist. (DOC 218 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Swystun, V., Green, F.H.Y., Dennis, J.H. et al. A phase IIa proof-of-concept, placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind, crossover, single-dose clinical trial of a new class of bronchodilator for acute asthma. Trials 19, 321 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2720-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2720-6