Abstract

Background

Metabolic syndrome is prevalent among Vietnamese adults, especially those aged 50–65 years. This study evaluated the effectiveness of a 6 month community-based lifestyle intervention to increase physical activity levels and improve dietary behaviours for adults with metabolic syndrome in Vietnam.

Methods

Ten communes, involving participants aged 50–65 years with metabolic syndrome, were recruited from Hanam province in northern Vietnam. The communes were randomly allocated to either the intervention (five communes, n = 214) or the control group (five communes, n = 203). Intervention group participants received a health promotion package, consisting of an information booklet, education sessions, a walking group, and a resistance band. Control group participants received one session of standard advice during the 6 month period. Data were collected at baseline and after the intervention to evaluate programme effectiveness. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form and a modified STEPS questionnaire were used to assess physical activity and dietary behaviours, respectively, in both groups. Pedometers were worn by the intervention participants only for 7 consecutive days at baseline and post-intervention testing. To accommodate the repeated measures and the clustering of individuals within communes, multilevel mixed regression models with random effects were fitted to determine the impacts of intervention on changes in outcome variables over time and between groups.

Results

With a retention rate of 80.8%, the final sample comprised 175 intervention and 162 control participants. After controlling for demographic and other confounding factors, the intervention participants showed significant increases in moderate intensity activity (P = 0.018), walking (P < 0.001) and total physical activity (P = 0.001), as well as a decrease in mean sitting time (P < 0.001), relative to their control counterparts. Significant improvements in dietary behaviours were also observed, particularly reductions in intake of animal internal organs (P = 0.001) and in using cooking oil for daily meal preparation (P = 0.001).

Conclusions

The prescribed community-based physical activity and nutrition intervention programme successfully improved physical activity and dietary behaviours for adults with metabolic syndrome in Vietnam.

Trial registration

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry, ACTRN12614000811606. Registered on 31 July 2014

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes that includes abdominal obesity, elevated blood pressure, reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, elevated fasting triglyceride and high glucose concentrations [1]. Metabolic syndrome is becoming a global epidemic [2] and is often undiagnosed [3, 4], with about one-quarter of the adult population worldwide affected by the condition [5]. In Vietnam, it has been reported that almost two-fifths of adults aged 35–65 years have metabolic syndrome [6]. A recent cross-sectional study found that 16.3% of the Vietnamese population aged 40–64 years have metabolic syndrome, while those aged 55–64 sustain the highest prevalence and account for 27% of the cases diagnosed [7].

Modifiable lifestyle factors, such as physical inactivity and unhealthy dietary habits, are associated with the development of metabolic syndrome [6–8]. It is estimated that 28.7% of Vietnamese adults are insufficiently active (<600 metabolic equivalent tasks (MET), min per week) [9]. Moreover, the household food consumption pattern has changed rapidly [10], with increases in intake of dietary sodium and saturated fat [10, 11]. The proportion of energy intake from fat has doubled from 8.4% to 17.6% in the last two decades [10]. It has been reported that physical inactivity and insufficient vegetable and fruit consumption are responsible for 0.7% and 3.07%, respectively, of the total burden of disease in Vietnam. These unhealthy lifestyle behaviours have also contributed to over 5% of deaths from non-communicable disease [9]. In recognition of the high mortality and morbidity associated with non-communicable disease in Vietnam, the National Strategy for Non-Communicable disease Control and Prevention 2015–2025 was established to reduce behavioural risk factors, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and salt consumption [12].

Interventions that use a combination of physical activity training and dietary modification have been recommended for metabolic syndrome [3, 13]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that interventions that motivate participants to improve lifestyle behaviours and weight management are essential for controlling metabolic syndrome risk factors [14]. Reported outcomes of intervention strategies designed to improve physical activity and dietary behaviours vary in terms of effectiveness [14]. However, a systematic review found that participation in walking groups provides an effective way of increasing physical activity and is suitable for any age group, especially older adults [15]. Walking, as a moderate activity, is the most popular leisure activity across all socio-economic groups [16, 17]. Walk leaders, who are either volunteers or nominated by their group members, have been demonstrated to play a key role in motivating participants to become physically active [16, 18].

With regard to resources, interventions that incorporate an information booklet to improve knowledge are found to be effective [19–21]. For example, a recent study in rural Western Australia that made use of an information booklet achieved positive changes in physical activity and dietary behaviours for participants with or at risk of metabolic syndrome [22]. Furthermore, personal feedback and group support are important for lifestyle interventions to control metabolic syndrome and its risk factors [14].

In view of the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome among middle-aged people in Vietnam [7, 9, 23], the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme was designed to target adults aged 50–65 years with metabolic syndrome. The aim of this study was to determine whether implementation of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme was effective in terms of improving physical activity levels and dietary behaviours of its participants after a 6 month intervention.

Methods

Study design

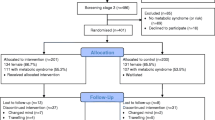

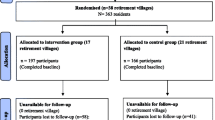

The protocol of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme has been described in detail previously [24], in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement (see Fig. 1 for the CONSORT flow chart and Additional file 1 for the CONSORT checklist of the trial). It was a 6 month community-based cluster-randomized controlled trial targeting adults aged 50–65 years with metabolic syndrome from 10 communes in Hanam province, northern Vietnam. Outcomes were collected from intervention and control groups at baseline and post-intervention testing. The trial was registered with the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN12614000811606). The research protocol was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: HR139/2014). Written informed consent was sought from each participant prior to entry in the trial.

Participants

Adults aged 50–65 years with metabolic syndrome were recruited and invited to participate in the study. Metabolic syndrome status was determined based on the modified National Cholesterol Education Programme Adult Treatment Panel III criteria of having three of the five risk factors [25]: (1) large waist circumference (male ≥90 cm, female ≥80 cm, for Asian population [1]; (2) raised triglyceride levels (≥1.7 mmol/l or 150 mg/dl); 3) reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (male <1.03 mmol/l or 40 mg/dl, female <1.29 mmol/l or 50 mg/dl); (4) raised blood pressure (systolic ≥130 mmHg or diastolic ≥85 mmHg); and (5) raised fasting plasma glucose level (≥6.1 mmol/l or ≥110 mg/dl).

Exclusion criteria were suspected type 2 diabetes (fasting plasma glucose level ≥7.1 mmol/l); treatment or a history of treatment for type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, dyslipidaemia, hyperglycaemia, and hypertension; or involvement in a physical activity or dietary programme within the previous year.

Procedure

The participant selection phase, including initial screening and determination of metabolic syndrome status, occurred between October 2014 and January 2015, and the post-intervention evaluation was completed in November 2015.

Screening

A total of 8560 adults aged 50–65 years residing in 10 randomly selected communes within Hanam province were contacted, and invited to attend their local commune health centre for screening. Small incentives (reimbursement of transport expenses) were provided to encourage attendance. At these sessions, a short interview was conducted to obtain information about each participant’s age, sex, physical activity levels, and medication history. The participant’s height and weight were also measured. Body mass index was calculated and classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for Asian populations, with body mass index ≥23 being classed as ‘overweight’ [26]. Eligible people with body mass index ≥23 were invited to participate in the next stage of screening.

Determining metabolic syndrome status

As shown in Fig. 1, 1515 eligible subjects were invited for blood testing and measurement of waist circumference and blood pressure to confirm their metabolic syndrome status. A formal letter of invitation was delivered to eligible participants. The letter provided detailed information about the time, location, and guidelines for fasting overnight (except for water after 9 p.m. and on the morning of blood sample collection). However, only 1244 people attended the clinic for blood sample collection and anthropometric measurements. Among them, 422 met the metabolic syndrome criteria and were invited for baseline evaluation. Five individuals changed their minds and subsequently withdrew, leaving a total of 417 participants who completed the baseline assessment.

Allocation to control and intervention groups

The 10 selected communes were randomly allocated to either the intervention group (five communes, n = 214) or the control group (five communes, n = 203) by a member of staff at Hanam Provincial Preventive Medicine Centre using a table of random numbers. The intervention group underwent the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme, whereas the control group participants, who were fully aware of their status, received one session of standard advice and were wait-listed to receive the intervention package following completion of the post-intervention test. At the end of the 6 months period, 175 intervention (response rate 81.8%), and 162 control participants (response rate 79.8%) completed the post-intervention test assessment; see Fig. 1.

Intervention

The intervention was developed and underpinned by social cognitive theory [27, 28]. It was designed to promote physically activity and the maintenance of a healthy diet to participants. The Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme included four education sessions, a booklet, a resistance band and walking groups. All components of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme were conducted within the participants’ communes to minimize subject burden. Participants attended four 2-hour education sessions at months 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the intervention, and participated in walking groups established at each commune for 6 months. During the first education session, each participant was provided with the health promotion booklet and a resistance band for strength exercises. Programme staff at the Hanam Provincial Preventive Medicine Centre, trained by the first author, conducted the education sessions, led the walking groups and collected data from participants at baseline and post-intervention testing. These trained walk leaders were provided with a package containing the education materials, as well as a manual for managing the group walks. The walk leaders mobilized participants for walking and encouraged them to achieve physical activity and diet goals. Details of the intervention materials are described elsewhere [24].

Variables

Demographic and personal information such as age, sex, occupation, marital status, smoking and alcohol consumption was obtained through a structured questionnaire administered to participants via face-to-face interview at baseline testing.

Physical activity

The International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form, validated for Vietnamese adults [29], was used to measure physical activity levels, which included vigorous intensity activity, moderate intensity activity, walking and sitting time. In addition, a pedometer (Yamax SW-200, Japan) was given to each intervention participant to count daily steps taken. The device was fitted to the hip and worn for 7 consecutive days at both baseline and post-intervention testing. This objective measure of physical activity has been reported to be accurate and reliable [30].

Diet

The brief dietary habits questionnaire was modified from the STEPS questionnaire developed by the WHO [31] to gather information on the consumption of vegetables and fruits, and intake of animal internal organs, as well as the frequency of use of cooking oil and salt for preparing meals.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were first applied to summarize the baseline characteristics of the participants by group status. Comparisons between intervention and control participants were undertaken across the two time points using independent samples and paired t tests for continuous outcome variables, and the chi-squared test for dichotomous outcomes. For variables with skewed distributions, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Wilcoxon signed rank test were applied instead. To accommodate the correlation of observations due to the repeated measures (pre- and post-intervention testing) and the clustering of individuals within the 10 randomly selected communes, multilevel generalized linear mixed models with random effects (participants and communes) were fitted to determine the impacts of intervention on changes in outcome variables over time and between groups [32, 33], while accounting for the effects of potential confounding factors (age, sex, education level, relationship status, occupation, smoking status and alcohol consumption). All statistical analyses were performed in the SPSS package version 21.

Binary outcomes

In the presence of many zeros, vigorous activity and moderate activity were dichotomized by participation status (yes, no). For dietary behaviour outcomes, consumption of fruit and vegetables, using cooking oil and salt to prepare meals at least once per day, as well as consumption of animal internal organs more than twice per month, were classified as frequent intake or usage (yes, no). These binary outcomes (vigorous activity, moderate activity, frequent fruit intake, frequent vegetable intake, frequent intake of animal internal organs, frequent use of cooking oil, frequent use of salt) were modelled using logistic mixed regressions.

Continuous outcomes

Walking time was considered a continuous variable in metabolic equivalent tasks (MET, min/week). Total physical activity for each individual was calculated by summing across the three activity domains, in which the reported time spent (min/week) was multiplied by the corresponding MET score (8 for vigorous, 4 for moderate and 3.3 for walking) [34]. Sitting time was analyzed in terms of duration (min/week). Generalized linear mixed regression analysis was applied to walking time and total physical activity (MET, min/week), which were logarithmic transformed owing to their positively skewed distributions. A gamma mixed regression model was adopted to analyze the highly skewed sitting time.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of participants at baseline, with no significant differences observed between the intervention and control groups (P > 0.05). The mean age of the participants was 57 (standard deviation, 5) years, with the majority being women. More than 90% of the cohort completed secondary school or higher, and over 90% lived with a partner. Almost one-third of the sample were retired. On average, the participants were slightly overweight, with a mean body mass index of 25.1 (standard deviation, 2).

Physical activity outcomes

Table 2 compares the physical activity outcomes over time and between intervention and control groups. Both groups were similar in terms of physical activity levels at baseline. However, significant improvements (P < 0.001) were observed in the intervention group from baseline to post-intervention testing for moderate activity participation, walking time and total physical activity, as well as a reduction in sitting time. There was also a significant increase (P = 0.011) of over 5000 steps on average on 7 consecutive days between the two time points. For the control group, no significant change occurred from baseline to post-intervention testing, apart from an apparent decrease in mean sitting time.

Table 3 summarizes the results of mixed regression analyses of physical activity outcomes pre- and post-intervention. After controlling for commune clustering and the effects of confounding factors, significant improvements among the intervention participants relative to their control counterparts were evident in moderate activity participation (P = 0.018), mean walking time (P < 0.001), total physical activity (P = 0.001) and mean sitting time (P < 0.001), according to the group × time interaction term of the mixed regression models. However, no significant change in prevalence of vigorous activity participation was found after the intervention (P = 0.643).

Dietary outcomes

Table 4 shows that both groups were similar with respect to the reported dietary behaviour outcomes at baseline, but that the intervention participants appeared more likely to consume fruits than the controls. Significant improvements in some of these dietary outcomes from baseline to post-intervention testing were observed for the intervention group, whereas no apparent changes were found in the control group, apart from a decrease in frequent use of salt for preparing meals. At 6 months, significant differences between groups were demonstrated for all dietary behaviours (P < 0.05).

Table 5 summarizes the results of logistic mixed regression analyses of dietary behaviours before and after intervention. After controlling for commune clustering and the effects of confounding factors, the group × time interaction term confirmed significant reductions in frequent intake of animal internal organs (P = 0.001) as well as frequent use of cooking oil (P = 0.001) by the intervention group relative to the control group over the 6 month period.

Discussion

In this study, Vietnamese adults with metabolic syndrome were identified from individuals initially screened and recruited from the community. The final sample of 337 participants at the post-intervention evaluation represented an overall retention rate of 80.8%, which was higher than in previous studies [22, 35]. The low attrition may reflect the acceptability of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme to the participants. Indeed, the group leaders were specifically trained to improve retention and engagement of participants in their walking groups, while the physical activity and healthy eating information provided in the booklet and education sessions was relevant and appropriate for the target group. Such strategies have been found to boost retention successfully in intervention studies [36, 37].

The results demonstrated changes in physical activity and dietary behaviours among the intervention participants when compared with the controls. Our findings were consistent with those from previous studies in terms of physical activity and nutrition outcomes [18, 22, 35, 38]. For example, a recent home-based intervention on Australian adults with, or at risk of, metabolic syndrome reported a significant increase in moderate activity and a reduction in sitting time among intervention participants [22]. In particular, the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme had led to significant improvements in moderate activity participation, walking time and total physical activity, as well as a reduction in sitting time for the intervention group. In addition, data recorded by pedometers confirmed a substantial increase of 5160 steps taken on average after the intervention, consistent with findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis [39]. Significant improvements in waist circumference (−1.63 cm, P < 0.001) and weight (−1.44 kg, P < 0.001) among the intervention group compared with the control group after controlling for the effects of clustering and confounding factors were also found [40].

The Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme followed the WHO’s Recommendations for Physical Activity [41], encouraging participants to undertake at least 150 min of moderate intensity activity per week, or equivalent. This message was reinforced during the education sessions, while individuals were guided to tailor the programme to suit their own needs, such as walking more or walking less. Advice and regular feedback were provided by the walk leaders and programme facilitators to monitor dietary and physical activity behaviours [14, 37]. The adopted approach not only supported participants but also enabled them to manage their own progress, thereby increasing their sense of ownership of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme. Walking in groups has been shown to increase moderate physical activity among adults. It is accessible for everyone and is suitable for all socio-economic groups [15] especially older adults [16, 17], even those with chronic diseases [15]. The dramatic increase in walking among the intervention participants suggested the suitability of the walking group for Vietnamese adults with metabolic syndrome.

The nutrition component of the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme was developed based on the Food-Based Dietary Guidelines in Vietnam [42], which encouraged participants to eat more vegetables and fruits every day, reduce the amount of salt and cooking oil used when preparing meals, and reduce the consumption of animal internal organs. It also advised participants to eat boiled meals instead of stir-fried or deep-fried foods, together with tips on how to adhere to these guidelines, and goal setting. The intervention resulted in slight increases in the intake of daily fruit and vegetables, but since most participants already reported consumption at least once per day at baseline, further improvement was somewhat limited by the ‘ceiling effect’ [38]. However, significant reductions were achieved in the use of cooking oil (P = 0.001) and the consumption of animal internal organs (P = 0.001).

Understanding the barriers and enablers that influence physical activity and dietary behaviours can assist in the development of appropriate health promotion interventions [43]. The Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme undertook formative research to identify and address barriers that were subsequently incorporated into the programme. Experience, lessons and suggestions from other participants, as well as facilitators, on overcoming the barriers and on insights into enablers, were discussed throughout the education sessions and implemented in the programme.

Creating a supportive environment and establishing a network of new friends through the walking groups and educations sessions also enhanced positive behaviour changes. These strategies have previously been documented to improve physical activity [44] and might contribute to the improved outcomes for this study. Although the Hawthorne effect might affect behavioural changes [45], such an impact was expected to be minor for randomized controlled trials [46, 47].

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. The intervention programme was followed up for 6 months, in line with recommendation for metabolic syndrome control under supervision [48]. Assessment of sustainability of the programme and behavioural changes over a longer term is not feasible owing to budget constraint and resource limitations. Although demographic and other factors were controlled for in the mixed regression analyses, residual confounding may still exist and potentially affect the results. Another shortcoming concerned the objective measurement of physical activity, whereby pedometers were provided to the intervention participants only to motivate walking. The use of objective physical activity measures,such as pedometers and accelerometers, in both intervention and control groups should be considered in future research.

Conclusions

The Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme was the first physical activity and nutrition intervention specifically targeting Vietnamese adults with metabolic syndrome. This cluster-randomized controlled trial demonstrated increases in moderate intensity activity, walking and total physical activity, as well as reductions in sitting time, intake of animal internal organs and using cooking oil for daily meal preparation among the intervention participants, when compared with the control group over a 6 month period. The findings confirmed that the prescribed community-based intervention with supportive environments can effectively improve physical activity and dietary behaviours for adults with metabolic syndrome in Vietnam.

Abbreviations

- CONSORT:

-

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- MET:

-

metabolic equivalent task

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5.

Kaur J. A comprehensive review on metabolic syndrome. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014;2014:943162.

Blaha MJ, Bansal S, Rouf R, Golden SH, Blumenthal RS, Defilippis AP. A practical ‘ABCDE’ approach to the metabolic syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:932–41.

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52.

International Diabetes Federation. The IDF consensus worldwide definition of the Metabolic Syndrome. Belgium: IDF; 2006.

Duc Son LN, Kusama K, Hung NT, Loan TT, Chuyen NV, Kunii D, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetes in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Diabet Med. 2004;21:371–6.

Binh TQ, Phuong PT, Nhung BT, do Tung D. Metabolic syndrome among a middle-aged population in the Red River Delta region of Vietnam. BMC Endocr Disord. 2014;14:77.

Trinh OT, Nguyen ND, Phongsavon P, Dibley MJ, Bauman AE. Metabolic risk profiles and associated risk factors among Vietnamese adults in Ho Chi Minh City. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:69–78.

Harper C. Vietnam Noncommunicable Disease Prevention and Control Programme 2002–2010 implementation review. Manila: WHO Western Pacific Region; 2011.

National Institute of Nutrition of Vietnam. Summary Report General Nutrition Survey 2009-2010. National Institute of Nutrition. 2010. https://www.unicef.org/vietnam/summary_report_gsn.pdf.

Khan NC, Khoi HH. Double burden of malnutrition: the Vietnamese perspective. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17 Suppl 1:116–8.

The Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Decision No. 376/QD-TTg National Strategy for NCD Control and Prevention period 2015–2025. Hanoi: 2015

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement: executive summary. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2005;4:198–203.

Bassi N, Karagodin I, Wang S, Vassallo P, Priyanath A, Massaro E, et al. Lifestyle modification for metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2014;127:1242. e1-10.

Kassavou A, Turner A, French DP. Do interventions to promote walking in groups increase physical activity? A meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:18.

Jancey JM, Clarke A, Howat PA, Lee AH, Shilton T, Fisher J. A physical activity program to mobilize older people: a practical and sustainable approach. Gerontologist. 2008;48:251–7.

Ogilvie D, Foster CE, Rothnie H, Cavill N, Hamilton V, Fitzsimons CF, et al. Interventions to promote walking: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;334:1204.

Jancey JM, Lee AH, Howat PA, Clarke A, Wang K, Shilton T. The effectiveness of a physical activity intervention for seniors. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22:318–21.

Blackford K, Jancey J, Lee AH, James AP, Howat P, Hills AP, et al. A randomised controlled trial of a physical activity and nutrition program targeting middle-aged adults at risk of metabolic syndrome in a disadvantaged rural community. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:284.

Burke L, Howat P, Lee A, Jancey J, Kerr D, Shilton T. Development of a nutrition and physical activity booklet to engage seniors. BMC Res Notes. 2008;1:1–7.

Burke L, Jancey J, Howat PA, Lee AH, Kerr DA, Shilton T, et al. Physical activity and nutrition program for seniors (PANS): protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:751.

Blackford K, Jancey J, Lee AH, James A, Howat P, Waddell T. Effects of a home-based intervention on diet and physical activity behaviours for rural adults with or at risk of metabolic syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:13.

Hoy D, Rao C, Nhung NTT, Marks G, Hoa NP. Risk factors for chronic disease in Viet Nam: a review of the literature. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E05.

Tran VD, Lee AH, Jancey J, James AP, Howat P, Thi Phuong Mai L. Community-based physical activity and nutrition programme for adults with metabolic syndrome in Vietnam: study protocol for a cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011532.

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421.

Expert Consultation WHO. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. Lancet. 2004;363(9403):157–63.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997.

Glanz K, Rimer B, Viswanath K. Health behaviour and health education: theory, research and practice. 4th ed. San Francisco: Wiley; 2008.

Tran DV, Lee AH, Au TB, Nguyen CT, Hoang DV. Reliability and validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form for older adults in Vietnam. Health Promot J Austr. 2013;24:126–31.

Le Masurier GC, Lee SM, Tudor-Locke C. Motion sensor accuracy under controlled and free-living conditions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:905–10.

WHO. WHO STEPS Surveillance Manual. Geneva: WHO; 2008.

Casals M, Girabent-Farrés M, Carrasco JL. Methodological quality and reporting of generalized linear mixed models in clinical medicine (2000–2012): a systematic review. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112653.

Bolker BM, et al. Generalized linear mixed models: a practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol Evol. 2009;24(3):127–35.

The IPAQ Group. Guidelines for Data Processing and Analysis of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). 2004. http://www.institutferran.org/documentos/scoring_short_ipaq_april04.pdf.

Burke L, Lee AH, Jancey J, Xiang L, Kerr DA, Howat PA, et al. Physical activity and nutrition behavioural outcomes of a home-based intervention program for seniors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:14.

Jancey JM, Clarke A, Howat P, Maycock B, Lee AH. Perceptions of physical activity by older adults: a qualitative study. Health Educat J. 2009;68:196–206.

Kassavou A, Turner A, French DP. The role of walkers’ needs and expectations in supporting maintenance of attendance at walking groups: a longitudinal multi-perspective study of walkers and walk group leaders. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118754.

Lee AH, Jancey J, Howat P, Burke L, Kerr DA, Shilton T. Effectiveness of a home-based postal and telephone physical activity and nutrition pilot program for seniors. J Obes. 2011;2011:786827.

Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):751–8.

Tran VD, James AP, Lee A, Jancey J, Howat P, Thi Phuong Mai L. Effectiveness of a community-based physical activity and nutrition behaviour intervention on features of the metabolic syndrome: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2016. doi:10.1089/met.2016.0113.

WHO. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010.

National Institute of Nutrition of Vietnam. Food-based dietary guidelines – Vietnam. 2011. http://viendinhduong.vn/news/en/714/123/food-based-dietary-guidelines---viet-nam.aspx. Accessed 3 May 2016.

Cleland V, Hughes C, Thornton L, Squibb K, Venn A, Ball K. Environmental barriers and enablers to physical activity participation among rural adults: a qualitative study. Health Promot J Austr. 2015;26:99–104.

Ståhl T, Rütten A, Nutbeam D, Bauman A, Kannas L, Abel T, et al. The importance of the social environment for physically active lifestyle – results from an international study. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1–10.

Parsons HM. What happened at Hawthorne? New evidence suggests the Hawthorne effect resulted from operant reinforcement contingencies. Science. 1974;183:922–32.

McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:267–77.

O’Sullivan I, Orbell S, Rakow T, Parker R. Prospective research in health service settings: health psychology, science and the ‘Hawthorne’ effect. J Health Psychol. 2004;9:355–9.

Schwellnus MP, Patel DN, Nossel CJ, Dreyer M, Whitesman S, Derman EW. Healthy lifestyle interventions in general practice Part 6: Lifestyle and metabolic syndrome. S Afr Fam Pract. 2009;51:177–81.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the residents of Hanam province who participated in the study. Thanks are also due to the Hanam Provincial Preventive Medicine Centre for participant recruitment and support during the trial.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the researchers’ institution only.

Availability of data and materials

The intervention materials are available from the first author upon request. Individual information will not be released owing to confidentiality agreements signed by the study participants.

Authors’ contributions

VDT coordinated the Vietnam Physical Activity and Nutrition programme and drafted the manuscript. AHL, JJ, APJ, PH, and LTPM designed the study, developed the research protocol and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: HR139/2014). Written informed consent was sought from all participants prior to entry into the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

CONSORT checklist of the trial. (PDF 138 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, V.D., Lee, A.H., Jancey, J. et al. Physical activity and nutrition behaviour outcomes of a cluster-randomized controlled trial for adults with metabolic syndrome in Vietnam. Trials 18, 18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1771-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1771-9