Abstract

Background

Previous studies have shown that reproductive factors are differentially associated with breast cancer (BC) risk by subtypes. The aim of this study was to investigate associations between reproductive factors and BC subtypes, and whether these vary by age at diagnosis.

Methods

We used pooled data on tumor markers (estrogen and progesterone receptor, human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)) and reproductive risk factors (parity, age at first full-time pregnancy (FFTP) and age at menarche) from 28,095 patients with invasive BC from 34 studies participating in the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC). In a case-only analysis, we used logistic regression to assess associations between reproductive factors and BC subtype compared to luminal A tumors as a reference. The interaction between age and parity in BC subtype risk was also tested, across all ages and, because age was modeled non-linearly, specifically at ages 35, 55 and 75 years.

Results

Parous women were more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative BC (TNBC) than with luminal A BC, irrespective of age (OR for parity = 1.38, 95% CI 1.16–1.65, p = 0.0004; p for interaction with age = 0.076). Parous women were also more likely to be diagnosed with luminal and non-luminal HER2-like BCs and this effect was slightly more pronounced at an early age (p for interaction with age = 0.037 and 0.030, respectively). For instance, women diagnosed at age 35 were 1.48 (CI 1.01–2.16) more likely to have luminal HER2-like BC than luminal A BC, while this association was not significant at age 75 (OR = 0.72, CI 0.45–1.14). While age at menarche was not significantly associated with BC subtype, increasing age at FFTP was non-linearly associated with TNBC relative to luminal A BC. An age at FFTP of 25 versus 20 years lowered the risk for TNBC (OR = 0.78, CI 0.70–0.88, p < 0.0001), but this effect was not apparent at a later FFTP.

Conclusions

Our main findings suggest that parity is associated with TNBC across all ages at BC diagnosis, whereas the association with luminal HER2-like BC was present only for early onset BC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and leading cause of female cancer death [1]. Over the past decade, it has become evident that BC represents a heterogeneous disease, for which different subtypes can be distinguished based on the combination of tumor grade and the presence of hormone receptors, i.e., estrogen (ER), progesterone (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2). Each BC subtype, including the luminal A-like, luminal B-like, luminal HER2-like, HER2-like and triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), presents with different age and risk factor distributions [2]. Analyses from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium (BCAC) showed, for instance, that nulliparity and a later age at first full-time pregnancy (FFTP) increase the risk of ER-positive BC, but not ER-negative BC [3].

Menarche and FFTP, and in particular their timing, may have diverse and complex effects on BC risk. It has been proposed that pregnancy induces the protective differentiation of mammary cells in the terminal duct lobular unit, which translates into long-term protection against BC [4,5,6]. Subsequent full-term pregnancies exert a similar but quantitatively much less important effect, which is a likely reflection of the protective differentiation of breast cells already induced by the FFTP [7]. The protective effect of an FFTP, however, is not apparent when the FFTP occurs after the age of 35 years [8, 9]. Although an FFTP offers long-term protection against BC, pregnancy is also associated with a transient increased BC risk postpartum, which could be due to pregnancy-related stimulation of pre-existent malignant clones [7, 10, 11]. In addition, the protective effect of the FFTP is found to be greater later in life [12], which according to a hypothesis by Russo et al. can be explained by the fact that several breast tumors are already initiated before the pregnancy, i.e., before the FFTP can induce its protective effect [4, 5].

Age at menarche has also been reported to influence BC risk differently depending on age. A late age at menarche is associated with a later onset of ovulatory cycles, and consequently with a decreased lifetime exposure to estrogen [13, 14]. For instance, per one year younger age at menarche, the associated BC risk increases by about 7% in women aged < 45 years, whereas the increase is about 4% in women aged 65 or older [15]. Also a short window of susceptibility, which is defined as the time between age at menarche and age at FFTP, lowers BC risk [16].

So far, few studies have examined how reproductive variables may be differentially associated with the risk of a specific BC subtype [2, 17]. The majority of these studies did not consider differential effects by age or were typically limited to cases developing BC at young age [18, 19], or to postmenopausal women only [20, 21]. Additional investigations involving women diagnosed with BC in all age categories, for which data on BC subtypes are available, are thus warranted. Therefore, we examined the association between parity and the risk of developing a specific BC subtype, and how this may differ according to age. Furthermore, we assessed the association of age at menarche (in nulliparous and parous women) and age at FFTP with the risk of being diagnosed with a specific BC subtype.

Methods

BCAC cohorts, inclusion and exclusion criteria

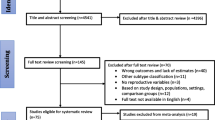

This analysis includes data from studies which participate in the BCAC and could provide information on BC risk factors, in particular parity (never versus ever), age at menarche and age at FFTP, and clinic-pathological information, in particular, grade, ER, PR and HER2 status of the tumor. Studies not providing any of these data were excluded. Three additional studies in the BCAC with information on BC subtypes were also not included: two studies included only ER-negative BC or patients with TNBC (SKKDKFZS, NBCS); one study included only ER-positive/non-TNBC patients (PBCS). Overall, 34 of the 49 available studies in the BCAC provided data justifying inclusion in our study. These were composed of 10 population-based studies (8 case–control and 2 prospective cohort studies); 5 hospital-based case-control studies; and 19 studies of mixed design (all other studies). No information on previous in situ BC was available, though some studies excluded patients with a previous BC. Figure 1 displays the numbers of excluded and included patients. Patients with in situ breast cancer (N = 3932) and patients with bilateral BC (N = 2349) were excluded, since interpretation may be difficult in the case of coexistence of different BC phenotypes. Patients with BC diagnosed during pregnancy (N = 23) were excluded as well. Patients with insufficient information for assignment to BC subtype according to the 2011 St. Gallen criteria [22] (N = 18,612) were also excluded. Patients with BC before a first pregnancy were classified as nulliparous. Only BC patients with an unambiguously defined surrogate molecular BC status (N = 11,328), and with a known parity and age at BC diagnosis were included (Fig. 1).

Tumor marker definitions and definition of breast cancer subtypes

Definitions of ER, PR and HER2 status were not standardized across studies since most data were extracted from medical records (15 of 34 studies for ER and PR, and 6 of 34 studies for HER2). The 2011 St. Gallen criteria were used to define the five surrogate BC molecular phenotypes, using grade instead of Ki67 positivity [22]: (i) luminal A-like (ER-positive and/or PR-positive, HER2-negative, grade 1 or 2), (ii) luminal B-like (ER-positive and/or PR-positive, HER2-negative, grade 3), (iii) luminal HER2-like (ER-positive and/or PR-positive and HER2-positive), (iv) HER2-like (ER-negative and PR-negative, HER2-positive), and TN (ER-negative, PR-negative and HER2-negative) BC. How these internationally accepted definitions relate to other definitions of BC subtypes, as previously also applied in other BCAC publications, is depicted in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Statistical methodology

To evaluate the interaction between parity and age at BC diagnosis considering all BC subtypes simultaneously, a baseline-category logit model was applied to a five-category polytomous variable consisting of the five BC molecular subtypes, whereby luminal A-like breast cancer was considered the reference category. Interactions between parity and age at BC diagnosis in the probability of developing a specific BC subtype were tested by separate logistic regression models with binary outcome (1 for the BC subtype and 0 for luminal A-like BC as the reference subtype). For age at diagnosis, non-linear trends were explored by means of quadratic and cubic spline-based curves. Likelihood ratio testing was used for model selection of nested models and akaike information criterion (AIC) in the case of un-nested models. The best fit was obtained when modeling age non-linearly using cubic splines (five knots). Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals were estimated across all ages and, since age at diagnosis was modeled non-linearly, extrapolated from the non-linear fit at three different ages: 35 years (premenopausal age), 55 years (early postmenopausal age) and 75 years (late postmenopausal age). Hence, odds ratios for parity at selected ages are deducted from the curves generated for all patients at all ages, and are not based on subgroups of patients at selected ages.

To follow up on a significant interaction between age at diagnosis (continuous) and parity in luminal HER2-like and HER2-like BC, which only differ in their ER/PR status, we tested whether this interaction varied by combined ER/PR status (ER+/PR+, ER-/PR+, ER+/PR- = 1, ER-/PR- = 0) by means of a three-way interaction test (age at diagnosis × parity × ER/PR status). The test was conducted using a binary logistic regression model (HER2 status negative/positive) with HER2-negative as the reference group. Additionally, we assessed the association between parity and HER2-positive BC by age at diagnosis, using luminal A-like BC as the reference subtype.

Associations of age at menarche (in parous and nulliparous women) and FFTP (in parous women only) with BC subtypes were evaluated using logistic regression models. Again, luminal A-like BC was used as the reference subtype. Age at BC diagnosis was included in these models to correct for possible confounding. In parous women, age at FFTP was modelled according to the best fit, i.e., as a linear function for luminal B-like, luminal HER2-like and HER2-like BC, but as a quadratic function for TNBC.

To account for clustering of patients by study, a multilevel (or random-effects) model was used to provide unbiased standard errors and p values [23]. All tests were two-sided and p values smaller than 0.05 were considered significant. The analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.2.

Results

Descriptive statistics for age at BC diagnosis, menopausal status, parity, age at menarche and age at FFTP stratified by molecular subtype are presented in Table 1. Additional information about these variables per individual study and for tumor size, nodal status, tumor grade and PR status can be found in Additional file 1: Tables S2-S4.

First, we assessed the association between parity and BC subtype compared to luminal A BC as a reference. This was done across all ages modeled non-linearly using cubic splines (see “Methods”), and because of the non-linear fit also extrapolated to specific ages. Table 2 includes specific estimates at 35, 55 and 75 years of age corresponding to premenopausal, early postmenopausal and late postmenopausal ages, whereas Additional file 1: Table S5 highlights estimates at 40, 50 and 60 years of age. A frequency table showing parity by BC subtype and specific age groups is provided as Additional file 1: Table S6. Parous women were more likely to develop TNBC compared to luminal A tumors (OR = 1.38, CI 1.16–1.65, p = 0.0004, Table 2), but this association did not vary significantly by age (p for interaction = 0.076). Graphical representation of these associations (Fig. 2a-d) nevertheless suggested that parous women were more likely to develop TNBC around age 55 years (Fig. 2d).

Association between parity and luminal B-like, luminal human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-like, HER2-like and triple-negative breast cancer by age at diagnosis. A binary logistic regression model was fitted considering every molecular subtype as the response variable, while considering luminal A-like breast cancer as a reference category, and parity and age as explanatory continuous variables. Age was modeled non-linearly using cubic splines (5 knots). Blue lines represent probabilities for parous women, green lines probabilities for nulliparous women. a Probability of luminal B-like subtype by parity. b Probability of Luminal HER2-like subtype by parity. c Probability of HER2-like subtype by parity. d Probability of triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtype by parity

Compared to luminal A tumors, we did not observe a significant association between parity and luminal B-like BC across all ages (OR = 0.90, CI 0.77–1.05, p = 0.18), nor at selected ages (Table 2 and Fig. 2a). For luminal HER2-like BC, there was also no significant association with parity across all ages (OR = 1.04, CI 0.88–1.24, p = 0.62). We did detect, however, a weak but significant interaction between parity and age (p for interaction = 0.037). Indeed, although confidence intervals were wide, parous women were slightly more likely to develop luminal HER2-like BC at age 35 (OR = 1.48, CI 1.01–2.16, p = 0.046). This association was not significant in women aged 55 (OR = 1.35, CI 0.92–1.99, p = 0.13) and was almost opposite in women aged 75 (OR = 0.72, CI 0.45–1.14, p = 0.16, Table 2 and Fig. 2b). Associations between parity and HER2-like breast tumors were similar to those observed for luminal HER2-like BC (Table 2 and Fig. 2c). There was indeed a significant interaction between parity and age (p for interaction = 0.030), but at specific ages ORs were not significant. Next, we combined luminal HER2-like and HER2-like BC and investigated whether parity may be associated with the likelihood of developing HER2+ BC (Table 3). A two-way interaction test between parity and age for HER2+ BC relative to luminal A BC was significant (p for interaction = 0.003), but a three-way interaction test between parity, age and ER/PR status revealed that the interaction between parity and age does not differ by ER/PR status (p for interaction = 0.49). Compared to luminal A BC, parous women were more likely to develop HER2+ BC at age 35 and 55 (OR = 1.44, CI 1.02–2.03, p = 0.037 and OR = 1.42, CI 1.04–1.96, p = 0.029, respectively), while an inverse association was observed at age 75 (OR = 0.67, CI 0.67–0.98, P = 0.041, Table 3). Figure 3 visualizes how the association between parity and HER2+ BC differs by age.

Association between parity and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) + breast cancer by age at diagnosis. A binary logistic regression model was fitted, considering HER2+ breast cancer as the response variable with luminal A-like breast cancer as the reference category. Age was modeled non-linearly using cubic splines (5 knots). Blue lines represent probabilities for parous women, green lines probabilities for nulliparous women

Next, we assessed whether age at menarche affected the likelihood of being diagnosed with a specific BC subtype, while considering luminal A BC as the reference. The results when parity was considered a dichotomous variable are presented in Table 4, while the data for parity as a continuous variable are presented in Additional file 1: Table S7. For both analyses, we found that in parous and nulliparous women, age at menarche was not significantly associated with any of the subtypes investigated, relative to luminal A BC.

Similar analyses were performed for age at FFTP. Increasing age at FFTP was non-linearly associated with the odds of being diagnosed with TNBC relative to luminal A BC. A FFTP at age 25 compared to age 20 years was associated with an OR of 0.78 (CI 0.70–0.88, p < 0.0001, Table 4). This association was not apparent for later ages of FFTP. Indeed, patients with a FFTP at age 35 compared to 30 years did not have reduced odds of being diagnosed with TNBC compared to luminal A BC (OR = 1.11, CI 0.96–1.28, p = 0.15), whereas TNBC patients with a FFTP at age 30 versus 25 years exhibited an intermediate association (OR = 0.93, CI = 0.86–1.01, p = 0.07). For the other BC subtypes, we observed no association with age at FFTP (Table 4). Notably, similar effects were observed when including body mass index (BMI) as a potential confounder in these analyses (Additional file 1: Table S8).

Finally, we also performed a joint analysis to simultaneously assess the association of age at menarche and age at FFTP with BC subtypes (Table 4). Overall, associations were very similar to the associations observed when evaluating age at menarche and age at FFTP separately.

Discussion

Our analyses in pooled data on 11,328 patients with invasive BC showed that parity is associated with TNBC relative to luminal A disease, irrespective of age at diagnosis. A weak association between parity and luminal HER2-like BC on the other hand could only be observed when assessed at different ages. Furthermore, age at FFTP was non-linearly associated with TNBC.

In an earlier case-only study using BCAC data [3], we reported that parity is associated with a greater probability of being diagnosed with TNBC compared to ER+/HER- or PR+/HER- tumors. In the current analysis, this was confirmed, but relative to luminal A tumors. We did not observe that this association differed significantly according to age (p = 0.076), although the effects appeared slightly stronger with older age.

Also in line with previous results reported by the BCAC [3], parity was not associated with HER2-positive BC (both luminal HER2-like and HER2-like BC), while using luminal A-like (HER2-negative) BC as the reference. However, we did observe for the first time that this association differed significantly by age. Parous women diagnosed at 35 years of age were more likely to present with luminal HER2-like or HER2-like rather than luminal A BC (OR = 1.44), whereas parous women diagnosed after the menopause, at 75 years of age, were not (OR = 0.67). We hypothesize that pregnancy may promote HER2 positivity in BCs that are already sub-clinically present during pregnancy, but only become clinically apparent in the years following pregnancy. With older age, we found that parous women are less likely to have HER2-positive BC. Here, pregnancy could induce a protective effect against HER2-positive BCs. Phipps et al. also reported an association between late age at FFTP and increased risk of HER2-like BC, suggesting that there may only be a protective effect of pregnancy against HER2-positive BC when pregnancy precedes carcinogenesis [24].

Several studies already also reported that BC risk varies in the function of the time window between age at menarche and age at FFTP, with most studies suggesting that a short time interval is significantly and inversely associated with ER-positive BC [16, 18, 25, 26]. In the current study, we were able to provide a more detailed analysis of this effect. With respect to age at FFTP, we found that with an older age at FFTP, women were less likely to be diagnosed specifically with TNBC. Interestingly, this association seemed to be stronger for younger ages at FFTP (20–25 years) than for older ages at FFTP (30–35 years). On the other hand, age at menarche was not differentially associated with BC subtypes.

These findings should now be confirmed in large population-based studies. Indeed, the design of our case-only study, in which we calculated odds ratios using luminal A BC as a reference, does not allow us to estimate absolute BC subtype risk. So far, most population-based studies observed a significant inverse association between parity and hormone receptor-positive BC, although none of these studies took age into account [2, 17]. One recent study investigated whether associations between reproductive factors and premenopausal BC differed before and after age 40 years. The inverse association between parity and hormone receptor-positive BC was only observed in women aged > 40 years [27]. Most studies have not identified a statistically significant relationship between parity and the risk of TNBC [2], although one study in women aged between 20 and 44 years observed that a short time interval between menarche and FFTP was associated with an increased risk of TNBC [18]. Again, it should be noted that these studies did not assess differential effects by age or were focused on specific ages of diagnosis, and were often also hampered by the low prevalence of TNBC compared to hormone receptor-positive BC. Possibly, our findings may be explained by Russo’s hypothesis, which suggests that some BCs develop at a younger age (i.e., prior to the pregnancy) [4, 5]. Protection against hormone receptor-positive BC due to a pregnancy may thus result in a relative increase in TNBC at a later age, especially around 55 years, as suggested in this study.

The strength of this study is its large sample size with comprehensive data on molecular markers and other detailed data derived from pathology reports. As such, we were able to derive BC molecular subtypes, which are known to differ in their prognosis, for all included patients. Importantly, we also used clinical criteria based on the 2011 St. Gallen report to refine the definition of the molecular subtypes. We failed, however, to detect obvious differences between luminal B and luminal HER2+ BC with the reproductive factors under study, suggesting that both groups in fact behaved similarly. Our sample size was slightly smaller compared to the previous BCAC study by Yang et al. [3], due to the fact that information on grade had to be available in addition to ER, PR and HER2 status to define subtypes according to the 12th St. Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference Expert Panel [22]. A potential limitation of this study is that data were derived from studies with various designs and methods to obtain risk factor and marker data. Furthermore, a relatively large proportion of patients were diagnosed at a young age, because some participating studies oversampled younger patients with BC and patients with a familial history of BC. In the future, since several new studies have joined BCAC and are in the process of providing more detailed reproductive risk factor data, we plan to take the effect of other variables such as body mass index, age at last pregnancy and breastfeeding into account. However, as we conducted case-case analyses by including a random effect for study in all models and also adjusted for age at diagnosis whenever applicable, it is unlikely that this may have affected our results.

Conclusion

We report that parity is differentially associated with BC subtypes and that the association for HER2-positive BC (relative to luminal A BC) depends on the patient’s age, but not on ER/PR status. Later age at FFTP was also inversely associated with TNBC, which suggests that an early pregnancy may increase the likelihood of developing TNBC relative to luminal A BC. Our results have to be confirmed in large population-based studies. However, they provide further support for different etiology between BC subtypes and suggest that models used to predict BC risk should take this into account.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BCAC:

-

Breast Cancer Association Consortium

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FFTP:

-

First full-time pregnancy

- HER2:

-

Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- TNBC:

-

Triple negative breast cancer

References

DeSantis CE, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):252–71.

Anderson KN, Schwab RB, Martinez ME. Reproductive risk factors and breast cancer subtypes: a review of the literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(1):1–10.

Yang XR, et al. Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: a pooled analysis from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium Studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(3):250–63.

Russo J, et al. Breast differentiation and its implication in cancer prevention. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(2 Pt 2):931s–6s.

Russo J, et al. The protective role of pregnancy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(3):131–42.

Ma H, et al. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R43.

Lambe M, et al. Parity, age at first and last birth, and risk of breast cancer: a population-based study in Sweden. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38(3):305–11.

Adami HO, et al. Age at first birth, parity and risk of breast cancer in a Swedish population. Br J Cancer. 1980;42(5):651–8.

MacMahon B, Cole P, Brown J. Etiology of human breast cancer: a review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1973;50(1):21–42.

Schedin P. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(4):281–91.

Pathak DR. Dual effect of first full term pregnancy on breast cancer risk: empirical evidence and postulated underlying biology. Cancer Causes Control. 2002;13(4):295–8.

Clavel-Chapelon F, Gerber M. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk. Do they differ according to age at diagnosis? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;72(2):107–15.

Apter D, Vihko R. Early menarche, a risk factor for breast cancer, indicates early onset of ovulatory cycles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57(1):82–6.

Pike MC, et al. Estrogens, progestogens, normal breast cell proliferation, and breast cancer risk. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(1):17–35.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast, C. Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(11):1141–51.

Li CI, et al. Timing of menarche and first full-term birth in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(2):230–9.

Horn J, et al. Reproductive history and the risk of molecular breast cancer subtypes in a prospective study of Norwegian women. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25(7):881–9.

Li CI, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of estrogen receptor positive, triple-negative, and HER2-neu overexpressing breast cancer among women 20-44 years of age. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137(2):579–87.

Gaudet MM, et al. Risk factors by molecular subtypes of breast cancer across a population-based study of women 56 years or younger. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):587–97.

Ma H, et al. Pregnancy-related factors and the risk of breast carcinoma in situ and invasive breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the California Teachers Study cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(3):R35.

Lord SJ, et al. Breast cancer risk and hormone receptor status in older women by parity, age of first birth, and breastfeeding: a case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(7):1723–30.

Goldhirsch A, et al. Strategies for subtypes–dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1736–47.

Aerts M. Topics in modelling of clustered data. Monographs on statistics and applied probability. Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2002. p. 308.

Phipps AI, et al. Reproductive and hormonal risk factors for postmenopausal luminal, HER-2-overexpressing, and triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(7):1521–6.

Chung S, et al. Association between chronological change of reproductive factors and breast cancer risk defined by hormone receptor status: results from the Seoul Breast Cancer Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140(3):557–65.

Ritte R, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of hormone receptor positive and negative breast cancer: a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:584.

Warner ET, et al. Reproductive factors and risk of premenopausal breast cancer by age at diagnosis: are there differences before and after age 40? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142(1):165–75.

Acknowledgements

We give special thanks to all our study participants, without whose cooperation this study could not have been done.

Funding

BCAC is funded by Cancer Research UK (C1287/A10118, C1287/A12014) and by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under grant agreement number 223175 (grant number HEALTH-F2-2009-223175) (COGS). The Australian Breast Cancer Family Study (ABCFS) was supported by grant UM1 CA164920 from the National Cancer Institute (USA). The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centers in the Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the USA Government or the BCFR. The ABCFS was also supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the New South Wales Cancer Council, the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (Australia) and the Victorian Breast Cancer Research Consortium. J.L.H. is a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Senior Principal Research Fellow. M.C.S. is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow. The ABCS study was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (grants NKI 2007-3839; 2009 4363); BBMRI-NL, which is a Research Infrastructure financed by the Dutch government (NWO 184.021.007); and the Dutch National Genomics Initiative. The ACP study is funded by the Breast Cancer Research Trust, UK. The work of the BBCC was partly funded by ELAN-Fond of the University Hospital of Erlangen. The CECILE study was funded by Fondation de France, Institut National du Cancer (INCa), Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, Ligue contre le Cancer Grand Ouest, Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire (ANSES), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR). The CGPS was supported by the Chief Physician Johan Boserup and Lise Boserup Fund, the Danish Medical Research Council and Herlev Hospital. The CNIO-BCS was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, the Red Temática de Investigación Cooperativa en Cáncer and grants from the Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer and the Fondo de Investigación Sanitario (PI11/00923 and PI12/00070). The ESTHER study was supported by a grant from the Baden Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research and Arts. Additional cases were recruited in the context of the VERDI study, which was supported by a grant from the German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe). The GENICA was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Germany grants 01KW9975/5, 01KW9976/8, 01KW9977/0 and 01KW0114, the Robert Bosch Foundation, Stuttgart, Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), Heidelberg, the Institute for Prevention and Occupational Medicine of the German Social Accident Insurance, Institute of the Ruhr University Bochum (IPA), Bochum, as well as the Department of Internal Medicine, Evangelische Kliniken Bonn gGmbH, Johanniter Krankenhaus, Bonn, Germany. The HEBCS was financially supported by the Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Fund, Academy of Finland (266528), the Finnish Cancer Society, The Nordic Cancer Union and the Sigrid Juselius Foundation. The HERPACC was supported by MEXT Kakenhi (No. 170150181 and 26253041) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology of Japan, by a Grant-in-Aid for the Third Term Comprehensive 10-Year Strategy for Cancer Control from Ministry Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, by Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants for Research on Applying Health Technology from Ministry Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan, by National Cancer Center Research and Development Fund, and “Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control (15ck0106177h0001)” from Japan Agency for Medical Research and development, AMED, and Cancer Bio Bank Aichi. Financial support for KARBAC was provided through the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Cancer Society, The Gustav V Jubilee foundation and and Bert von Kantzows foundation. The KARMA study was supported by Märit and Hans Rausings Initiative Against Breast Cancer. The KBCP was financially supported by the special Government Funding (EVO) of Kuopio University Hospital grants, Cancer Fund of North Savo, the Finnish Cancer Organizations, and by the strategic funding of the University of Eastern Finland. kConFab is supported by a grant from the National Breast Cancer Foundation, and previously by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), the Queensland Cancer Fund, the Cancer Councils of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia, and the Cancer Foundation of Western Australia. Financial support for the AOCS was provided by the United States Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (DAMD17-01-1-0729), Cancer Council Victoria, Queensland Cancer Fund, Cancer Council New South Wales, Cancer Council South Australia, The Cancer Foundation of Western Australia, Cancer Council Tasmania and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC; 400413, 400281, 199600). G.C.T. and P.W. are supported by the NHMRC. RB was a Cancer Institute NSW Clinical Research Fellow. LAABC is supported by grants (1RB-0287, 3 PB-0102, 5 PB-0018, 10 PB-0098) from the California Breast Cancer Research Program. Incident breast cancer cases were collected by the USC Cancer Surveillance Program (CSP) which is supported under subcontract by the California Department of Health. The CSP is also part of the National Cancer Institute's Division of Cancer Prevention and Control Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program, under contract number N01CN25403. LMBC is supported by the ‘Stichting tegen Kanker’ (232-2008 and 196-2010). Diether Lambrechts is supported by the FWO and the KULPFV/10/016-SymBioSysII. The MARIE study was supported by the Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V. (70-2892-BR I, 106332, 108253, 108419), the Hamburg Cancer Society, the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Germany (01KH0402). MBCSG is supported by grants from the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) and by funds from the Italian citizens who allocated the 5/1000 share of their tax payment in support of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori, according to Italian laws (INT-Institutional strategic projects “5x1000”). The MCBCS was supported by the NIH grants CA192393, CA116167, CA176785 an NIH Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Breast Cancer (CA116201), and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation and a generous gift from the David F. and Margaret T. Grohne Family Foundation. MCCS cohort recruitment was funded by VicHealth and Cancer Council Victoria. The MCCS was further supported by Australian NHMRC grants 209057, 251553 and 504711 and by infrastructure provided by Cancer Council Victoria. Cases and their vital status were ascertained through the Victorian Cancer Registry (VCR) and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), including the National Death Index and the Australian Cancer Database. MYBRCA is funded by research grants from the Malaysian Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (UM.C/HlR/MOHE/06) and Cancer Research Initiatives Foundation (CARIF). Additional controls were recruited by the Singapore Eye Research Institute, which was supported by a grant from the Biomedical Research Council (BMRC08/1/35/19/550), Singapore and the National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/CG/SERI/2010). The OBCS was supported by research grants from the Finnish Cancer Foundation, the Academy of Finland (grant number 250083, 122715 and Center of Excellence grant number 251314), the Finnish Cancer Foundation, the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the University of Oulu, the University of Oulu Support Foundation and the special Governmental EVO funds for Oulu University Hospital-based research activities. The Ontario Familial Breast Cancer Registry (OFBCR) was supported by grant UM1 CA164920 from the National Cancer Institute (USA). The content of this manuscript does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Cancer Institute or any of the collaborating centers in the Breast Cancer Family Registry (BCFR), nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the USA Government or the BCFR. The ORIGO study was supported by the Dutch Cancer Society (RUL 1997-1505) and the Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI-NL CP16). The RBCS was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (DDHK 2004-3124, DDHK 2009-4318). The SASBAC study was supported by funding from the Agency for Science, Technology and Research of Singapore (A*STAR), the US National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. The SBCGS was supported primarily by NIH grants R01CA64277, R01CA148667, and R37CA70867. Biological sample preparation was conducted using the Survey and Biospecimen Shared Resource, which is supported by P30 CA68485. The scientific development and funding of this project were, in part, supported by the Genetic Associations and Mechanisms in Oncology (GAME-ON) Network U19 CA148065. The SBCS was supported by Yorkshire Cancer Research S295, S299, S305PA and Sheffield Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre. SEARCH is funded by a programme grant from Cancer Research UK (C490/A10124) and supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. SEBCS was supported by the BRL (Basic Research Laboratory) program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012-0000347). The TBCS was funded by The National Cancer Institute Thailand. The TWBCS is supported by the Taiwan Biobank project of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Academia Sinica, Taiwan. The UKBGS is funded by Breast Cancer Now and the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), London. ICR acknowledges NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

OL wrote the manuscript and made substantial contributions towards the conception and design of the analyses and the interpretation of data. AR wrote the manuscript and made substantial contributions towards the conception and design of the analyses and the interpretation of data. AL conducted the statistical analyses. RK made substantial contribution to the acquisition of data. MKB made substantial contribution to coordinating the acquisition of data. QW made substantial contribution to coordinating the acquisition of data. AS made substantial contribution to the acquisition of data and interpretation of data. HW made substantial contribution to the acquisition of data and interpretation of data. ILA contributed to data acquisition. VA contributed to data acquisition. MWB contributed to data acquisition. JB contributed to data acquisition. CB contributed to data acquisition. SEB contributed to data acquisition. HB contributed to data acquisition. PB contributed to data acquisition. HB contributed to data acquisition. GCT contributed to data acquisition. JC contributed to data acquisition. SC contributed to data acquisition. FC contributed to data acquisition. AC contributed to data acquisition. SSC contributed to data acquisition. KC contributed to data acquisition. ME contributed to data acquisition. PAF contributed to data acquisition. JF contributed to data acquisition. HF contributed to data acquisition. GGG contributed to data acquisition. AGN contributed to data acquisition. PG contributed to data acquisition. PH contributed to data acquisition. AH contributed to data acquisition. JLH contributed to data acquisition. HI contributed to data acquisition. MJ contributed to data acquisition. DK contributed to data acquisition. JAK contributed to data acquisition. VMK contributed to data acquisition. JiLi contributed to data acquisition. AL contributed to data acquisition. JeLi contributed to data acquisition. AL contributed to data acquisition. AM contributed to data acquisition. SiMa contributed to data acquisition. SaMa contributed to data acquisition. KeMa contributed to data acquisition. KeMu contributed to data acquisition. HN contributed to data acquisition. PP contributed to data acquisition. KP contributed to data acquisition. SS contributed to data acquisition. CS contributed to data acquisition. CYS contributed to data acquisition. XOS contributed to data acquisition. MCS contributed to data acquisition. AS contributed to data acquisition. SHT contributed to data acquisition. RAT contributed to data acquisition. TT contributed to data acquisition. CCT contributed to data acquisition. AJB contributed to data acquisition. CHMVD contributed to data acquisition. RW contributed to data acquisition. AHW contributed to data acquisition. CHY contributed to data acquisition. JCY contributed to data acquisition. WZ contributed to data acquisition. RLM contributed to data acquisition. PDPP contributed towards conception and design of the study. DFE contributed towards conception and design of the study. MKS contributed to data acquisition and towards conception and design of the study. MGC contributed to data acquisition and towards conception and design of the study. JCC contributed to data acquisition and towards conception and design of the study. DL contributed towards conception and design, coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript. PN contributed towards conception and design of the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of each study was given by the local institutional review boards. All participants included in this study provided written consent.

Consent for publication

No individual-level data are presented in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Definitions of breast cancer subtypes that have been applied in previous BCAC manuscripts. Table S2 Number of breast cancer patients with reproductive risk factor data in the 34 BCAC studies assessed in this study. Table S3 Number of breast cancer case patients with tumor marker data in the 34 BCAC studies assessed in this study. Table S4 Distribution of tumor characteristics according to breast cancer subtypes. Table S5 Association between parity (ever versus never) and BC subtypes for age overall and for specific ages (40, 50 and 60 years). Table S6 Frequency table showing parity by subtype and age group. Table S7 Associations between age at menarche, age at FFTP and breast cancer subtypes. The same analysis as in Table 4 is performed but here parity is considered a continuous variable. Table S8 Effect of parity (ever versus never) on BC subtype risk across all ages at BC diagnosis and corrected for BMI. Associations between age at menarche, age at FFTP and breast cancer subtype risk. (DOCX 60 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Brouckaert, O., Rudolph, A., Laenen, A. et al. Reproductive profiles and risk of breast cancer subtypes: a multi-center case-only study. Breast Cancer Res 19, 119 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-017-0909-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-017-0909-3