Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the physiological impact of airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) on patients with early moderate-to-severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) by electrical impedance tomography (EIT).

Methods

In this single-center prospective physiological study, adult patients with early moderate-to-severe ARDS mechanically ventilated with APRV were assessed by EIT shortly after APRV (T0), and 6 h (T1), 12 h (T2), and 24 h (T3) after APRV initiation. Regional ventilation and perfusion distribution, dead space (%), shunt (%), and ventilation/perfusion matching (%) based on EIT measurement at different time points were compared. Additionally, clinical variables related to respiratory and hemodynamic condition were analyzed.

Results

Twelve patients were included in the study. After APRV, lung ventilation and perfusion were significantly redistributed to dorsal region. One indicator of ventilation distribution heterogeneity is the global inhomogeneity index, which decreased gradually [0.61 (0.55–0.62) to 0.50 (0.42–0.53), p < 0.001]. The other is the center of ventilation, which gradually shifted towards the dorsal region (43.31 ± 5.07 to 46.84 ± 4.96%, p = 0.048). The dorsal ventilation/perfusion matching increased significantly from T0 to T3 (25.72 ± 9.01 to 29.80 ± 7.19%, p = 0.007). Better dorsal ventilation (%) was significantly correlated with higher PaO2/FiO2 (r = 0.624, p = 0.001) and lower PaCO2 (r = -0.408, p = 0.048).

Conclusions

APRV optimizes the distribution of ventilation and perfusion, reducing lung heterogeneity, which potentially reduces the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

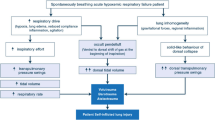

Airway pressure release ventilation (APRV) is a highly effective strategy improving lung recruitment and oxygenation in clinical studies, but its effects on lung injury and mortality is debatable [1, 2]. Animal studies revealed that APRV could normalize post-injury heterogeneity and reduce the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) [3, 4]. However, the physiological effects of APRV on patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) have yet to be thoroughly investigated due to the unavailability of point-of-care evaluation method.

Electrical impedance tomography (EIT), a noninvasive, bedside, and radiation-free technique, has been proposed as a valid method monitoring lung ventilation and perfusion [5]. To uncover the underlying physiological mechanism, we assessed the impact of APRV on lung ventilation and perfusion in patients with early moderate-to-severe ARDS by EIT.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a prospective, observational study in the general ICU of Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China, from March 2022 to June 2022. The study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Union Hospital (NO. 2022–0048). Written informed consents were obtained from the patients’ legal representatives. The study was registered before enrollment at chictr.org.cn (ChiCTR2200057638).

Patients

The inclusion criteria were moderate-to-severe ARDS patients (defined as PaO2/ FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg with positive end-expiratory pressure ≥ 5 cmH2O according to the Berlin definition [6]), endotracheal mechanical ventilation ≤ 48 h before enrollment, and expected to require continuous invasive mechanical ventilation ≥ 72 h. The exclusion criteria are provided in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Study protocol

We screened all adult, mechanically ventilated patients. Those patients who fulfilled the criteria for ARDS were submitted to a stabilization phase during which they were ventilated with volume-controlled, assist/control mode in accordance with the recommendations of the ARDS Network [7] (detailed procedures refer to Additional file 1). At the end of this stabilization period, patients were included if they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and baseline respiratory mechanics were measured. Then all patients were ventilated in APRV mode (C500 Infinity ventilator, Dräger, Germany). Patients were deeply sedated and, if necessary, paralyzed to abrogate spontaneous breathing if PaO2/FiO2 < 150 mmHg, whereas spontaneous breathing was permitted in patients with PaO2/FiO2 ≥ 150 mmHg, respiratory rate less than 35 bpm, and no significant patient-ventilator asynchrony [8, 9]. Every patient maintained normovolemia during APRV.

Settings of APRV were standardized for all patients as follows. (1) Initially, high airway pressure (PHigh) was set at the plateau pressure from volume control ventilation not to exceed 30 cmH2O and low airway pressure (PLow) was set at 0 cm H2O. The release time (TLow) was set at 0.3 to 0.6 s with I:E ratio 9:1 and adjusted to achieve an end-expiratory flow rate equal to 50–75% of the peak expiratory flow rate. (2) If patients develop SpO2 < 90%, three options are available (detailed method refer to Additional file 1): increase PHigh by 2 cmH2O until a maximum of 30 cmH2O, increase the time of high airway pressure (THigh) by 0.5 s (with an unaltered TLow, increased THigh implied an increased I:E ratio and a decreased respiratory rate), and increase FiO2. (3) If patients develop PaCO2 > 60 mmHg, THigh can be decreased to achieve greater mandatory respiratory rate, or PHigh can be increased by 2 cmH2O until a maximum of 30 cmH2O. (4) If the PaO2/FiO2 does not improve or remains below 150 mmHg, prone positioning will be considered. (5) If refractory hypoxemia persists, recruitment maneuver and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation will be considered.

EIT assessment (detailed procedures refer to Additional file 1, Figure S1) was administered shortly after APRV (T0), and 6 h (T1), 12 h (T2), and 24 h (T3) after APRV initiation. Parameters of ventilator, respiratory mechanics, and hemodynamics were also recorded at T0, T1, T2, and T3 before EIT assessment. Arterial blood gases analysis was recorded at T0 and T3.

Study outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was regional tidal volume distribution after 24 h of APRV. The second endpoints were global inhomogeneity (GI) index, center of ventilation (CoV), regional perfusion distribution, dead space-EIT (%), shunt-EIT (%), Ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) matching (%), and clinical variables related to respiratory and hemodynamic condition.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were computed with GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation or median (25–75th), as appropriate. A paired t-test was used to compare the paired data. Repeated measures ANOVA or Friedman test was applied with post-hoc Bonferroni’s or Dunn’s multiple comparisons to compare the data obtained at each time points, as appropriate. Correlation between continuous variables was assessed by the nonparametric Spearman correlation. A level of p value less than 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Twelve ARDS patients (9 male, 3 female) were included in the study. Mean age was 53.67 ± 12.37 years. There were 5 (42%) patients with severe ARDS and 7 (58%) patients with moderate ARDS. More detailed clinical characteristics of the study population were presented in Additional file 1: Table S2. During APRV, no patient developed barotrauma (pneumothorax, mediastinal emphysema, or subcutaneous emphysema), and all patients were in supine position.

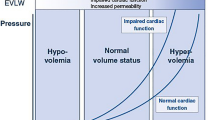

Data from EIT-based measurements showed that the regional lung ventilation and perfusion significantly redistributed from the ventral to dorsal region following ARPV application (Table 1). The median GI index of ventilation progressively decreased [0.61 (0.55–0.62) to 0.50 (0.42–0.53), p < 0.001], and CoV gradually changed towards dorsal regions (43.31 ± 5.07 to 46.84 ± 4.96%, p < 0.05). Patients trend to have an increased global V/Q matching (%) (63.41 ± 13.47 to 68.58 ± 11.70%) and decreased shunt-EIT (%) (13.80 ± 7.53 to 8.39 ± 5.18%) from T0 to T3, but not significantly; however, the dorsal V/Q matching (%) increased significantly (25.72 ± 9.01 to 29.80 ± 7.19%, p = 0.007) (Fig. 1). In subgroup analysis, patients with moderate ARDS had a significant increase in global V/Q matching (%) (58.88 ± 14.34 to 67.60 ± 12.75%, p = 0.019) and a decrease in global functional shunt (16.78 ± 7.81 to 9.16 ± 5.92%, p = 0.040), whereas patients with severe ARDS had no improvement (Fig. 1).

Evolution of global shunt-EIT (%), dead space-EIT (%), and V/Q matching (%) at T0, T1, T2 and T3 (A). Evolution of V/Q matching (%) in ventral and dorsal region at T0, T1, T2 and T3 (B). Subgroup analysis of V/Q matching (%), shunt-EIT (%), and dead space-EIT (%) evolution at T0, T1, T2, and T3 (C, D). Patients were divided into two subgroups based on the severity of ARDS: moderate ARDS with seven patients (C) and severe ARDS with five patients (D). Better dorsal ventilation (%) was significantly correlated with higher PaO2/FiO2 (E) and lower PaCO2 (F). V/Q, ventilation/perfusion; EIT, Electrical impedance tomography; ARDS, acute respiratory syndrome. T0: shortly after APRV; T1, T2, and T3: 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h after APRV application. *p < 0.05

From T0 to T3, median respiratory system static compliance after APRV application increased from 32.15 (27.11–42.30) to 37.95 (36.00–44.25) mL/cmH2O (p = 0.030). Additionally, PaO2/FiO2 increased from 109.5 ± 36.44 to 222.2 ± 58.46 mmHg significantly (p < 0.001), and PaCO2 decreased from 44.27 ± 8.58 to 36.78 ± 4.20 mmHg significantly (p = 0.032). Better dorsal ventilation (%) was significantly correlated with higher PaO2/FiO2 (r = 0.624, p = 0.001) and lower PaCO2 (r = -0.408, p = 0.048) (Fig. 1). No significant difference was identified in hemodynamic variables.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study using EIT to assess the physiological effects of APRV on lung ventilation and perfusion distribution, and V/Q matching in patients with early moderate-to-severe ARDS.

This study showed that dorsal region recruited after 24 h of APRV; moreover, the lung ventilation became more homogenous according to the results of GI index and CoV, suggesting that APRV has the potential to reduce the risk of VILI. Interestingly, we observed that ventilation redistributed prior to perfusion redistribution, implying that optimized ventilation facilitated in perfusion improvement. Dorsal alveolar recruitment reduced pulmonary vascular resistance, facilitating significant improvement of dorsal perfusion and V/Q matching. On the contrary, if lung inflation caused overexpansion rather than alveolar recruitment, an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance in hyperinflated regions would also direct perfusion toward nonaerated dorsal regions, ultimately leading to increased functional shunt and dead space [10].

The number of unmatched regions is associated with ARDS severity and the risk of VILI, as well as being an independent predictor of mortality [11]. Our study showed that V/Q matching improved and functional shunt decreased significantly in the moderate ARDS subgroup after 24 h APRV. Unfortunately, no significant improvement in V/Q matching was observed in severe ARDS, which could be attributed to the lack of significant improvement in perfusion redistribution (Additional file 1: Table S3). Pulmonary microvascular thrombosis, endothelial swelling and damage, and abnormal vasocontraction could lead to significant local hypoperfusion or even vascular occlusion, resulting in increased dead space [12]. In this situation, in addition to alveolar recruitment, inhaled pulmonary vasodilators, anti-inflammatory, or anticoagulation might be used as adjunctive therapy, but the evidence is limited, necessitating additional research [13].

There are several limitations in our study. First, the sample size was limited. Second, we didn’t focus on the effects of spontaneous breathing on APRV. The effects of APRV with or without spontaneous breathing on ARDS patients are still being debated [14]. Third, EIT only provides a cross-sectional lung-region analysis, which may differ from whole-lung evaluation. Forth, cardiac output was not measured in this cohort. Fifth, we didn’t measure end expiratory lung volume to assess any variation induced by APRV. Finally, there was no control group. Future research should focus on these issues.

Conclusions

APRV is a strategy based on pathophysiology that provides lung recruitment, stabilization, and homogeneity, potentially protecting injured lungs in patients with early moderate-to-severe ARDS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APRV:

-

Airway pressure release ventilation;

- VILI:

-

Ventilator-induced lung injury

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- EIT:

-

Electrical impedance tomography

- VCV:

-

Volume-controlled ventilation

- V/Q:

-

Ventilation/perfusion

- GI:

-

Global inhomogeneity

- CoV:

-

Center of ventilation

References

Zhou Y, Jin X, Lv Y, Wang P, Yang Y, Liang G, Wang B, Kang Y. Early application of airway pressure release ventilation may reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(11):1648–59.

Ibarra-Estrada MA, Garcia-Salas Y, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Lopez-Pulgarin JA, Chavez-Pena Q, Garcia-Salcido R, Mijangos-Mendez JC, Aguirre-Avalos G. Use of airway pressure release ventilation in patients with acute respiratory failure due to COVID-19: results of a single-center randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(4):586–94.

Kollisch-Singule M, Emr B, Smith B, Roy S, Jain S, Satalin J, Snyder K, Andrews P, Habashi N, Bates J, et al. Mechanical breath profile of airway pressure release ventilation: the effect on alveolar recruitment and microstrain in acute lung injury. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(11):1138–45.

Kollisch-Singule M, Emr B, Smith B, Ruiz C, Roy S, Meng Q, Jain S, Satalin J, Snyder K, Ghosh A, et al. Airway pressure release ventilation reduces conducting airway micro-strain in lung injury. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(5):968–76.

Jimenez JV, Weirauch AJ, Culter CA, Choi PJ, Hyzy RC. Electrical impedance tomography in acute respiratory distress syndrome management. Crit Care Med. 2022;50(8):1210–23.

Force ADT, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E, Camporota L, Slutsky AS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526–33.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome N, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, Wheeler A: Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2000, 342(18):1301–1308.

Papazian L, Aubron C, Brochard L, Chiche JD, Combes A, Dreyfuss D, Forel JM, Guerin C, Jaber S, Mekontso-Dessap A, et al. Formal guidelines: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):69.

Tasaka S, Ohshimo S, Takeuchi M, Yasuda H, Ichikado K, Tsushima K, Egi M, Hashimoto S, Shime N, Saito O, et al. ARDS Clinical Practice Guideline 2021. J Intensive Care. 2022;10(1):32.

Musch G, Harris RS, Vidal Melo MF, O’Neill KR, Layfield JD, Winkler T, Venegas JG. Mechanism by which a sustained inflation can worsen oxygenation in acute lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;100(2):323–30.

Spinelli E, Kircher M, Stender B, Ottaviani I, Basile MC, Marongiu I, Colussi G, Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Mauri T. Unmatched ventilation and perfusion measured by electrical impedance tomography predicts the outcome of ARDS. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):192.

Beda A, Winkler T, Wellman TJ, De Prost N, Tucci M, Vidal Melo MF. Physiological mechanism and spatial distribution of increased alveolar dead-space in early ARDS: an experimental study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021;65(1):100–8.

Rialp G, Betbese AJ, Perez-Marquez M, Mancebo J. Short-term effects of inhaled nitric oxide and prone position in pulmonary and extrapulmonary acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(2):243–9.

Andrews P, Shiber J, Madden M, Nieman GF, Camporota L, Habashi NM. Myths and misconceptions of airway pressure release ventilation: getting past the noise and on to the signal. Front Physiol. 2022;13: 928562.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to professor Haibo Qiu for his guidance on the conception of this study. We are also grateful to Zhaohui Fu, Hong Liu, and Xiaobo Yang for their generous support to this study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors met authorship criteria and participated significantly in the study. LY, XZ and YS were involved in the conception and design. All authors contributed to data collection or analysis. RL, YW, HZ, AW and XZ wrote the manuscript with supervision of LY, XZ and YS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of Union Hospital (NO. 2022–0048) and written informed consent was obtained from the patients’ legal representatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

ZZ receives consulting fee from Draeger Medical. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Methods. Table S1.

Exclusion criteria. Table S2. Patients’ main characteristics. Table S3. Subgroup analysis of ventilation and perfusion distribution evolution at T0, T1, T2, and T3. Fig. S1. Ventilation and perfusion measured by EIT in a representative patient at different time points.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Wu, Y., Zhang, H. et al. Effects of airway pressure release ventilation on lung physiology assessed by electrical impedance tomography in patients with early moderate-to-severe ARDS. Crit Care 27, 178 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04469-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04469-8