Abstract

Purpose

To study variation in, and clinical impact of high Therapy Intensity Level (TIL) treatments for elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) across European Intensive Care Units (ICUs).

Methods

We studied high TIL treatments (metabolic suppression, hypothermia (< 35 °C), intensive hyperventilation (PaCO2 < 4 kPa), and secondary decompressive craniectomy) in patients receiving ICP monitoring in the ICU stratum of the CENTER-TBI study. A random effect logistic regression model was used to determine between-centre variation in their use. A propensity score-matched model was used to study the impact on outcome (6-months Glasgow Outcome Score-extended (GOSE)), whilst adjusting for case-mix severity, signs of brain herniation on imaging, and ICP.

Results

313 of 758 patients from 52 European centres (41%) received at least one high TIL treatment with significant variation between centres (median odds ratio = 2.26). Patients often transiently received high TIL therapies without escalation from lower tier treatments. 38% of patients with high TIL treatment had favourable outcomes (GOSE ≥ 5). The use of high TIL treatment was not significantly associated with worse outcome (285 matched pairs, OR 1.4, 95% CI [1.0–2.0]). However, a sensitivity analysis excluding high TIL treatments at day 1 or use of metabolic suppression at any day did reveal a statistically significant association with worse outcome.

Conclusion

Substantial between-centre variation in use of high TIL treatments for TBI was found and treatment escalation to higher TIL treatments were often not preceded by more conventional lower TIL treatments. The significant association between high TIL treatments after day 1 and worse outcomes may reflect aggressive use or unmeasured confounders or inappropriate escalation strategies.

Take home message

Substantial variation was found in the use of highly intensive ICP-lowering treatments across European ICUs and a stepwise escalation strategy from lower to higher intensity level therapy is often lacking. Further research is necessary to study the impact of high therapy intensity treatments.

Trial registration

The core study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT02210221, registered 08/06/2014, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02210221?id=NCT02210221&draw=1&rank=1 and with Resource Identification Portal (RRID: SCR_015582).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Limiting the impact of secondary insults by controlling harmful levels of intracranial pressure (ICP) is an essential part of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) care in the intensive care unit (ICU). Interventions used to reduce ICP are typically titrated to balance their clinical effect against their side effects, which may be significant or even life-threatening. The intensity of such interventions can be quantified by the therapy intensity level (TIL) score. The TIL score was first introduced in 1987 [1], and has been revised over the years into a more advanced scoring system [2] which was recently validated [3]. Conceptually, the stepwise approach to treatment of raised ICP aims to use low tier therapies in the first instance, reserving more aggressive (and hazardous) high TIL treatments only for when these fail.

Despite this proposed framework for rational use of ICP therapies, past studies have found wide variations between centres in their deployment [4, 5]. Some of this variation may reflect either therapeutic nihilism or inappropriately aggressive use (as high intensity treatment can be clinically burdensome and consumes more ICU resources). While some studies report efficacy of high TIL therapies when properly targeted in terms of patient group and timing [6], other publications have given rise to concern that they may be ineffective in improving ultimate outcomes, and result in increased survival with severe disability [7, 8].

Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate the variation in the use of high TIL therapies in clinical practice and explore the impact on clinical outcome in patients with TBI in European ICUs.

Methods

CENTER-TBI study/ study population

Data from the Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER-TBI) study were used for this analysis (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02210221). CENTER-TBI recruited patients with TBI, presenting between December 19, 2014 and December 17, 2017 [9, 10]. Inclusion criteria for the CENTER-TBI study were: A clinical diagnosis of TBI, an indication for brain computer tomography (CT) and presentation within 24 h post-injury. Patients with severe pre-existing neurological disorders were excluded. For this study we selected patients of 14 years and older admitted to the ICU with documented daily measurements on the TIL scale for the first 7 days since admission to the ICU and with ICP monitoring.

Therapy intensity level

In the CENTER-TBI study, the most recent TIL scale is used [3] which measures and quantifies the intensity of ICP lowering treatments (and includes common data elements harmonized with the paediatric TIL scale [2]). The TIL scale consists of 8 ICP treatment modalities with corresponding scores for intensity, assessed daily [3] (Additional file 1: Supplement 1). High intensity ICP-lowering treatment is indicated by the use of one or more of the four treatments representing maximum therapy intensity on the TIL scale: Barbiturates (or high dose sedation) for metabolic (e.g. burst) suppression, secondary decompressive craniectomy, intensive hyperventilation to PaCO2 < 4 kPa, and hypothermia < 35 °C. We refer to patients who received any of these treatments at any point in time during their ICU stay as the ‘high TIL’ group. In addition, we excluded patients with decompressive craniectomy on day 1 (i.e. primary decompressive craniectomy) as such patients are likely to have a different pathophysiological trajectory and ICP therapy requirements due to a fundamental difference in intracranial compliance at the start of their ICU course. Such patients are also likely to be a distinct clinical entity (decompression at the time of space occupying lesion evacuation rather than for intractable intracranial hypertension) so their exclusion ensured a homogeneous population for a propensity score analysis. Maximum ICP prior to high TIL treatment (derived from 2 hourly measurements) was used as a measure of ICP burden.

Outcomes

Outcomes were collected at 6-months post-injury. Functional outcome was assessed on the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended (GOSE) using either an interview or questionnaire. Categories on the GOSE are: (1) Death, (2) Vegetative State, (3) Lower Severe Disability, (4) Upper Severe Disability, (5) Lower Moderate Disability, (6) Upper Moderate Disability, (7) Lower Good Recovery, and (8) Upper Good Recovery. Patients in categories (2) and (3) on the GOSE were combined in a single category. Health related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed with the Short Form 36v2 (SF-36) and the Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI) scale. For the SF-36, the Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) are expressed as T-scores. The QOLIBRI Total score has a range from 0 to 100.

Statistical analyses

We stratified the high- and low TIL treatment group and described their baseline characteristics and outcome by frequency/percentages for categorical variables and by median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Significant group differences were determined with the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, and ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis test (non-normal distributions) for continuous variables.

Missing data were imputed using multiple imputation (100 imputations, 5 iterations) using the MICE package for R statistical software (version 3.6.0) [11]. The distribution of missingness per variable (prior to imputation) is shown in Additional file 2: Supplement 2.

To calculate the between-centre variation in the use of high TIL therapies beyond that expected from case-mix severity and random variation, we used a random effects logistic regression model, with high TIL use as dependent variable and centre as random intercept. Covariates used were chosen from the extended International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials (IMPACT) prognostic model [12]. In addition, we adjusted for maximum recorded ICP values prior to high TIL treatment (as a surrogate for prior secondary injury and/or difficulty in achieving control), CT variables likely to be associated with the development of intracranial hypertension (brain herniation, cortical sulcus effacement, compression of one of more basal cisterns, midline shift and ventricular compression), as well as extracranial injury severity score (ISS; excluding the head injury component). Centre effects are expressed and plotted as random effects with corresponding confidence intervals at a log odds scale. We also quantified the between-centre variation with the median odds ratio (MOR): The MOR is a measure of the variance of the random effects [13]. The Nakagawa's R2 for mixed models was calculated to determine the variance in high TIL treatment explained by the variables in the model.

In previous studies, the aggressiveness of TBI management has been quantified based on the percentage use of ICP monitoring in patients who satisfied Brain Trauma Foundation (BTF) guidelines requirements for such monitoring. In order to examine whether this definition of aggressiveness based on use of a monitoring modality actually translated into aggressive management, we examined whether the percentage use of ICP monitoring in centres was related to the random effects of the use of high TIL per in the centre.

Finally, to study the association between high TIL treatment use and outcome, a propensity score matched model was constructed. This analysis determines whether the application of any high TIL therapy resulted in incremental harm (aggressiveness of treatment) beyond that caused by ICP elevation and case-mix severity. The primary outcome was the Glasgow Outcome Score-extended (GOSE) at 6 months, dichotomized into favourable (GOSE > 4) and unfavourable (GOSE ≤ 4). We used the random effects logistic regression model above to determine propensity scores for high TIL use. We applied nearest neighbour matching to select patients with a similar propensity scores but different treatment status. We compared the baseline characteristics between matched cases (with no missing data) and tested group differences (should be non-significant) and calculated the standardized mean differences (which should be low) to check match validity. In the matched cases, we compared the result of high versus low TIL treatment using a logistic regression with 6-month unfavourable GOSE as primary outcome. Two sensitivity analyses were performed to check whether the treatments were applied appropriately as high TIL practice. The first of these excluded high TIL treatments on day 1 to more faithfully reflect escalation of ICP therapy and discard non-treatment confounds (for example, hypothermia on day 1 may be injury related). Secondly, we considered the possibility that the use of barbiturates may have simply reflected therapy to target early / transient difficulties in controlling in ICP, rather than a sustained escalation of therapy. Consequently, the second sensitivity analysis excluded all barbiturate use as a high TIL treatment.

Analyses were performed using R statistical software [14]. The dataset was stored and accessed using the Opal [15] datamart. Dataset downloaded 06–02-2020 (Neurobot release 2.1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

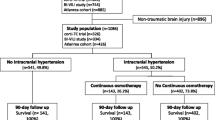

A total of 758 patients from 52 centres in Europe received ICP monitoring with documented TIL measurements during their ICU stay (Fig. 1, Additional file 4: Supplement 4, Additional file 6: Supplement 6). Of these, 313 patients (41.3%) received high TIL treatments at least once during their ICU stay. Table 1 summarises these groups. Patients who received high TIL treatment were generally younger, had better preinjury health status, and suffered from more severe brain trauma. Multimodal cerebral monitoring was generally more often used in high TIL patients.

Flowchart: patient inclusion. This flowchart is showing the inclusion of high TIL patients. High TIL patients were defined as patients receiving any treatment during ICU stay representing maximum therapy intensity of the TIL scale: Barbiturates for metabolic suppression, (secondary) decompressive craniectomy, intensive hyperventilation to PaCO2 < 4 kPa, and hypothermia < 35 °C at any point during their ICU stay

Patients requiring high TIL treatment generally had longer ICU stays and had a longer duration of mechanical ventilation (Table 2). Overall, high TIL and low TIL patients were discharged from the ICU with similar GCS scores. The complication rate was similar in the two groups, except for metabolic complications (high TIL: 14.0%, versus low TIL: 7.3% p = 0.004) (abnormalities in renal or liver function and electrolyte derangements).

Patterns of high TIL therapy use

Of the 313 patients, most received metabolic suppression while a minority of cases received intensive hyperventilation, intensive hypothermia, or secondary decompressive craniectomy (Additional file 3: Supplement 3, Additional file 5: Supplement 5). In general, TIL peaked after day 2, except for hypothermia (which was most commonly applied on day 1). In the majority of cases receiving high TIL treatment, head elevation, vasopressors and higher dose sedation had been used, but cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage, hyperosmolar therapies, and being nursed flat were recorded only in a minority of instances. Mean TIL scores in the high TIL group were below 10 points.

Between centre variation

Our study included 52 centres from 18 countries in the CENTER-TBI study. The median number of patients per centre was 11.5 [IQR 5–19]. Most centres used barbiturates (N = 46) while fewer centres used intensive hyperventilation (N = 21), hypothermia below 35 °C (N = 32), and decompressive craniectomy (N = 26). Based on treatment frequencies, there was a high degree of between centre variation in treatment choice. Overall, significant between centre variation beyond case mix and random variation (p < 0.001) was found in the use of high TIL treatments (MOR = 2.26). (Fig. 2, Additional file 7: Supplement 7). The Nakagawa's R2 showed that model variables ‘explained’ 8.7% of the (pseudo)variance in high TIL treatment use. Comparing measures of aggressiveness, the percentage use of ICP monitoring in patients who satisfied BTF guidelines was not related to the use of high TIL therapies by the centre (Fig. 3).

Between-centre variation in high TIL use. This figure shows the between-centre variation in the use of high TIL (Therapy Intensity Level) treatment. The use of high TIL per centre was adjusted for case-mix severity, brain herniation on imaging, maximum ICP value at the day of the start of high TIL treatment and random variation per centre with a random effects logistic regression model. For each centre, the random effect with corresponding 95% CI is plotted (average effect is log odds of zero). The MOR reflects the odds of high TIL treatment between two randomly selected centres for patients with the same case-mix severity (a higher MOR reflects larger between-centre variation) The MOR represents the median odds ratio; the higher the MOR the larger the between-centre variation (a MOR of 1 reflects no variation)

Definitions of aggressiveness. This figure illustrates the concordance between two definitions to identify aggressiveness of centers. On the x-axis is the definition of aggressiveness according to previous studies: the percentage of patients receiving ICP monitoring according to the BTF guidelines (GCS < 8 and abnormal CT, or normal CT and 2 or more of the following: hypotension, age > 40 years, unilateral or bilateral motor posturing, or systolic blood pressure (BP) < 90 mmHg). This percentage ICP monitoring was calculated in the ICU database (including all patients). On the y-axis is the definition of aggressiveness according to our study: the random effects of high TIL treatment per centers (log odds of receiving high TIL treatment). The upper right quadrant shows the centers that are both identified as aggressive by the previous definition (threshold 50% ICP monitoring) and the definition in our study (threshold random effect of zero).The lower left quadrant shows the centers that are identified as non-aggressive centers by both definitions. The two other quadrants show a discrepancy between the definitions of aggressiveness. Overall, there is no relationship between aggressiveness defined using ICP monitoring rates and actual use of aggressive therapies for ICP control

Impact of high TIL treatment on outcome

Although unfavourable outcome was more frequent in the high TIL group (62.5% versus 53.0%, p = 0.019)–a high proportion of high TIL patients nevertheless achieved a favourable outcome at 6 months (GOSE ≥ 5: N = 105; 37.5%). Mortality was significantly higher in the high TIL group (20.2% versus 13.3%, p = 0.016) (Fig. 4). The data on Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) are less complete than the GOSE, since in addition to loss to follow-up there are no scores for patients who die. Both groups had similar scores on the SF-36v2 MCS and PCS and the QOLIBRI total score. (Table 2).

Functional outcome at 6 months. This figure shows the functional outcome (GOSE) at 6 months for patients who receive low therapy and high therapy intensity. GOSE 1: death, 2: vegetative state, 3: severe disability lower, 4: severe disability upper, 5: moderate disability lower, 6: moderate disability upper, 7: good recovery lower, 8: good recovery upper. Patients in categories (2) and (3) on the GOSE were combined in a single category. GOSE: Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended, TIL: Therapy Intensity Level were combined in a single category. GOSE: Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended, TIL: Therapy Intensity Level

A total of 280 treated (high TIL) patients were well matched in terms of their baseline characteristics (Additional file 8: Supplement 8) and maximum ICP prior to TIL treatment did not differ between groups (Additional file 9: Supplement 9). With correction for maximum ICP prior to high TIL treatment; high TIL treatment was not significantly associated with unfavourable outcome (OR 1.4, 95% CI [0.98–1.96], p = 0.068). However, after the sensitivity analyses the association with worse outcome became significant for high TIL after day 1 (OR 1.5 CI [1.1–2.2], p = 0.023) and high TIL excluding barbiturates (OR 2.5 CI [1.4–4.7] p = 0.004). (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify treatments using the TIL scale in real-world clinical practice across centres in Europe. We report substantial between-centre variation in the choice and use of high TIL treatments in patients with TBI admitted to the ICU across Europe. Further, we did not observe a systematic progression in therapy intensity, exhausting low-tier treatments before escalating to more intensive therapies: instead high tier therapies were often used early in the course of treatment. This was unexpected, because progressive approach to treatment is recommended by the Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines [16] and forms part of the standard protocol in previous large clinical trials. In line with previous observational studies, we found relatively infrequent use of intensive hyperventilation, or decompressive craniectomy [17, 18]. In contrast, we found a relatively liberal use of barbiturates/deep sedation for metabolic suppression [19]. We found significant between centre variation in high TIL therapy use, beyond that accounted for by case-mix severity and random variation, both in terms of choice of therapy (e.g. use of hypothermia in a centre) and overall frequency of use (corrected for case-mix severity and random variation). This variation in high TIL treatment at centre-level suggests that, apart from disease severity, the clinical decision to use high TIL treatment is also based on institutional policy and culture.

After correction for ICP control, no statistically significant association was found between the use of high TIL treatment and functional outcome at 6 months. However, when excluding high TIL treatment at day 1 or barbiturates from high TIL treatment there was a statistically significant association with worse outcome. This may reflect some unquantified aspect of disease severity that is not captured by the available covariates but nevertheless translates into both TIL and outcome differences. Alternatively, this could mean that there is indeed some harm from residual high TIL therapies, in which case the use of these therapies before less hazardous low TIL options are exhausted could expose patients to unnecessary risks. Still, high-level evidence is lacking about the use of individual lower TIL therapies like CSF drainage and hyperosmolar fluids. This might explain why centres are cautious to apply these lower TIL treatments as standard use before proceeding to higher TIL treatment. Future studies are needed to confirm these findings as the sample size might have been insufficient to detect an association and to determine if a certain patient subgroup might benefit. High TIL treatments were associated with increased duration of ventilation and longer lengths of stay although we did not find a higher complication rate, at least for the metrics recorded. While we matched the two groups on available factors known to influence outcome, it is also possible that other aspects of the clinical course which we could not capture are also important in a clinician’s decision to institute high TIL therapies (residual confounding).

An important finding is that a large proportion of patients receiving high TIL treatments nevertheless recovered to good functional outcome (moderate disability to good recovery) at 6 months. High TIL treatment might be an appropriate final resource for patients with refractory high ICP values and may be beneficial in this group. Nevertheless, since there could be risks of such treatments, this emphasises the need for their rational use. More work is required to understand if outcome benefits could result from a more consistently gradated and progressive application of treatment intensity and/or a shift from institutional policies towards individualized medicine.

Previous studies have defined highly intensive (aggressive) treatment for ICP control in different ways [4,5,6,7, 20]. Cnossen et al. explored various definitions for aggressive treatment, such as the definitions ‘use of ICP monitoring in more than 50% in patients meeting the BTF guidelines criteria’ and ‘aggressiveness based on a TIL score (any of the following: osmotic therapy, hyperventilation, cerebrospinal fluid drainage, vasopressors for cerebral perfusion pressure support, hypothermia, barbiturates, and neurosurgical intervention)’ [4]. Bulger et al. also defined aggressiveness as ‘the use of ICP monitoring according to the BTF guidelines in more than 50% of patients’ [5]. However, this definition of aggressiveness (use of ICP monitoring) did not correlate with measured aggressiveness of therapy in our study, defined in our dataset as the likelihood of using high TIL therapies. We conclude that the previous use of higher use of ICP monitoring as a marker of aggressive TBI management in a centre may be flawed.

Several recent large trials have studied the impact on outcome of individual high TIL treatments, such as decompressive craniectomy [6, 8] or intensive hypothermia [21], but there is a need to assess other hazardous ICP-directed therapies (such as intensive hyperventilation and barbiturate coma) in this setting [16]. Our analysis targeted integrated assessment of all of these therapies, but the heterogeneity and lack of a uniform tiered approach to their use suggest that comparative effectiveness research (CER) approaches to exploring these therapies may have problems.

This study has a number of limitations that need to be discussed. First, the definition of a high TIL treatment is to some extent arbitrary as it is based on expert opinion rather than concrete outcome data. We considered metabolic suppression as a second-tier treatment, based on the recommendation in BTF guidelines that barbiturates should be considered a second-tier therapy (for raised ICP refractory to maximum treatment) [16]. However, our data suggest that in many centres others might consider this a first-tier/early therapy, in keeping with results from our Provider Profiling exercise [22]. In addition, we have no data on whether short durations of metabolic suppression in the early phase of illness carry the same risks as prolonged metabolic suppression employed as a treatment for refractory ICP in a later stage. Second, we do not have detailed data on how carefully these treatments were implemented, which is a significant omission. For example, the methods and rates of cooling or re-warming could affect both the efficacy and harm associated with intensive hypothermia. Finally, incomplete data on ICP monitoring made it difficult to accurately define a metric for poor ICP control before escalation of therapy and hence made propensity matching difficult. As poorly controlled ICP is likely to be a driver for escalation of therapy (or for continuing high TIL therapy), and also a marker of poor outcome, the absence of these data makes a rigorous covariate-adjusted comparison of high and low- TIL therapy groups difficult.

Future directions

Further work will be needed to explore the process by which clinical decisions to proceed to more intensive treatments are undertaken and determine the best way that hazardous therapies should be introduced in a rational tiered treatment plan. The evidence base to choose a particular high TIL treatment over another is limited, since the evidence on benefit from these therapies is either absent or conflicting [6,7,8, 21]. This lack of evidence helps to explain high between-centre variation in choice of treatment, and currently means that the initiation and choice of high TIL interventions is only driven by patient characteristics to a very limited extent and is primarily based on institutional policies. A better identification of subgroups of patients who benefit from such therapies would allow better targeting of either individual interventions, or high intensity therapies in general. We also need to explore whether more rigorous ICP control, with higher intensity therapies, may, in a subgroup of patients, prevent refractory intracranial hypertension, reduce ICU stay, and possibly improve outcome. The search for patient and monitoring characteristics that identify such a subgroup could allow a precision medicine approach to ICP management.

Conclusions

We show substantial variation amongst European centres in the choice and use of ICP-lowering treatments for patients with TBI. We found a no statistically significant association between the use of high TIL therapies and worse outcome after 6 months although a significant association did become apparent when day 1 or high dose sedation was excluded. However, this difference may have been flawed because of incomplete propensity matching of the high TIL and control groups due to unmeasured covariates. In any case, our results do not support a nihilistic view of patients who receive high TIL treatments; one third of high TIL patients achieved a favourable functional outcome, and high TIL treatment might have contributed to this. Further studies need to confirm whether and when high TIL treatments can be used as a safe final resort. More consistent use of low-tier treatments before escalating management to high TIL therapies, and data that support a rational choice of high TIL therapies, could both contribute to improved clinical outcome.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available via https://www.center-tbi.eu/data on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CENTER-TBI:

-

Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury

- CER:

-

Comparative effectiveness research

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid;

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- GOSE:

-

Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended

- HRQOL:

-

Health-Related Quality of Life

- ICP:

-

Intracranial pressure

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IMPACT:

-

International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- MOR:

-

Median odds ratio

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- TIL:

-

Therapy Intensity Level

- TBI:

-

Traumatic brain injury

References

Maset AL, Marmarou A, Ward JD, Choi S, Lutz HA, Brooks D, Moulton RJ, DeSalles A, Muizelaar JP, Turner H, et al. Pressure-volume index in head injury. J Neurosurg. 1987;67(6):832–40.

Shore PM, Hand LL, Roy L, Trivedi P, Kochanek PM, Adelson PD. Reliability and validity of the pediatric intensity level of therapy (PILOT) scale: a measure of the use of intracranial pressure-directed therapies. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(7):1981–7.

Zuercher P, Groen JL, Aries MJ, Steyerberg EW, Maas AI, Ercole A, Menon DK. Reliability and validity of the therapy intensity level scale: analysis of clinimetric properties of a novel approach to assess management of intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33(19):1768–74.

Cnossen MC, Polinder S, Andriessen TM, van der Naalt J, Haitsma I, Horn J, Franschman G, Vos PE, Steyerberg EW, Lingsma H. Causes and consequences of treatment variation in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury: a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(4):660–9.

Bulger EM, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Moore M, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ, Brain Trauma F. Management of severe head injury: institutional variations in care and effect on outcome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1870–6.

Hutchinson PJ, Kolias AG, Timofeev IS, Corteen EA, Czosnyka M, Timothy J, Anderson I, Bulters DO, Belli A, Eynon CA, et al. Trial of decompressive craniectomy for traumatic intracranial hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(12):1119–30.

Cooper DJ, Nichol AD, Bailey M, Bernard S, Cameron PA, Pili-Floury S, Forbes A, Gantner D, Higgins AM, Huet O, et al. Effect of early sustained prophylactic hypothermia on neurologic outcomes among patients with severe traumatic brain injury: the POLAR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(21):2211–20.

Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, Arabi YM, Davies AR, D’Urso P, Kossmann T, Ponsford J, Seppelt I, Reilly P, et al. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(16):1493–502.

Steyerberg EW ea: The contemporary landscape of traumatic brain injury in Europe: Case-mix, care pathways, and outcomes from the CENTER-TBI study. Lancet neurology 2019.

Maas AI, Menon DK, Steyerberg EW, Citerio G, Lecky F, Manley GT, Hill S, Legrand V, Sorgner A, Participants C-T, et al. Collaborative European neurotrauma effectiveness research in traumatic brain injury (CENTER-TBI): a prospective longitudinal observational study. Neurosurgery. 2015;76(1):67–80.

Van Buuren S. G-OK: mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 45. 2011.

Steyerberg EW, Mushkudiani N, Perel P, Butcher I, Lu J, McHugh GS, Murray GD, Marmarou A, Roberts I, Habbema JD, et al. Predicting outcome after traumatic brain injury: development and international validation of prognostic scores based on admission characteristics. PLoS Med. 2008;5(8):e165.

Merlo J, Chaix B, Ohlsson H, Beckman A, Johnell K, Hjerpe P, Rastam L, Larsen K. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(4):290–7.

Bonow RH, Quistberg A, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS. Intensive care unit admission patterns for mild traumatic brain injury in the USA. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(1):157–70.

Doiron D, Marcon Y, Fortier I, Burton P, Ferretti V. Software application profile: opal and mica: open-source software solutions for epidemiological data management, harmonization and dissemination. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(5):1372–8.

Brain Trauma F. American association of neurological s, congress of neurological s: guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(Suppl 1):S1-106.

Neumann JO, Chambers IR, Citerio G, Enblad P, Gregson BA, Howells T, Mattern J, Nilsson P, Piper I, Ragauskas A, et al. The use of hyperventilation therapy after traumatic brain injury in Europe: an analysis of the BrainIT database. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(9):1676–82.

Aarabi B, Hesdorffer DC, Ahn ES, Aresco C, Scalea TM, Eisenberg HM. Outcome following decompressive craniectomy for malignant swelling due to severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 2006;104(4):469–79.

Roberts I, Sydenham E. Barbiturates for acute traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012, 12:CD000033.

Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV. Does decompressive craniectomy improve outcomes in patients with diffuse traumatic brain injury? Med J Aust. 2011;194(9):437–8.

Andrews PJ, Sinclair HL, Rodriguez A, Harris BA, Battison CG, Rhodes JK, Murray GD, Eurotherm Trial C. Hypothermia for intracranial hypertension after traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(25):2403–12.

Cnossen MC, Huijben JA, van der Jagt M, Volovici V, van Essen T, Polinder S, Nelson D, Ercole A, Stocchetti N, Citerio G, et al. Variation in monitoring and treatment policies for intracranial hypertension in traumatic brain injury: a survey in 66 neurotrauma centers participating in the CENTER-TBI study. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):233.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients for their participation in the CENTER-TBI study. In addition, the authors would like to thank all principal investigators and researchers for ICU data collection and for sharing their valuable expertise (collaboration group).

Collaboration group: Cecilia Åkerlund1, Krisztina Amrein2, Nada Andelic3, Lasse Andreassen4, Audny Anke5, Gérard Audibert6, Philippe Azouvi7, Maria Luisa Azzolini8, Ronald Bartels9, Ronny Beer10, BoMichael Bellander11, Habib Benali12, Maurizio Berardino13, Luigi Beretta8, Erta Biqiri14, Morten Blaabjerg15, Stine Borgen Lund16, Camilla Brorsson17, Andras Buki18, Manuel Cabeleira19, Alessio Caccioppola20, Emiliana Calappi20, Maria Rosa Calvi8, Peter Cameron21, Guillermo Carbayo Lozano22, Marco Carbonara20, Ana M. CastañoLeón23, Giorgio Chevallard14, Arturo Chieregato14, Giuseppe Citerio24,25, Mark Coburn26, Jonathan Coles27, Jamie D. Cooper28, Marta Correia29, Endre Czeiter18, Marek Czosnyka19, Claire DahyotFizelier30, Véronique De31 Keyser31, Vincent Degos12, Francesco Della Corte32, Hugo den Boogert9, Bart Depreitere33, Dula Dilvesi34, Abhishek Dixit35, Jens Dreier36, GuyLoup Dulière37, Ari Ercole35, Erzsébet Ezer38, Martin Fabricius39, Kelly Foks40, Shirin Frisvold41, Alex Furmanov42, Damien Galanaud12, Dashiell Gantner21, Alexandre Ghuysen43, Lelde Giga44, Jagos Golubovic34, Pedro A. Gomez23, Francesca Grossi32, Deepak Gupta45, Iain Haitsma46, Raimund Helbok10, Eirik Helseth47, Peter J. Hutchinson48, Stefan Jankowski49, Mladen Karan34, Angelos G. Kolias48, Daniel Kondziella39, Evgenios Koraropoulos35, LarsOwe Koskinen50, Noémi Kovács51, Ana Kowark26, Alfonso Lagares23, Steven Laureys52, Aurelie Lejeune53, Roger Lightfoot54, Hester Lingsma55, Andrew I. R. Maas31, Alex Manara56, Costanza Martino57, Hugues Maréchal37, Julia Mattern58, Catherine McMahon59, David Menon35, Tomas Menovsky31, Davide Mulazzi20, Visakh Muraleedharan60, Lynnette Murray21, Nandesh Nair31, Ancuta Negru61, David Nelson1, Virginia Newcombe35, Quentin Noirhomme52, József Nyirádi2, Fabrizio Ortolano20, JeanFrançois Payen62, Vincent Perlbarg12, Paolo Persona63, Wilco Peul64, Anna Piippo-Karjalainen65, Horia Ples61, Inigo Pomposo22, Jussi P. Posti66, Louis Puybasset67, Andreea Radoi68, Arminas Ragauskas69, Rahul Raj65, Jonathan Rhodes70, Sophie Richter35, Saulius Rocka69, Cecilie Roe71, Olav Roise72,73, Jeffrey V. Rosenfeld74, Christina Rosenlund75, Guy Rosenthal42, Rolf Rossaint26, Sandra Rossi63, Juan Sahuquillo68, Oddrun Sandro76, Oliver Sakowitz58,77, Renan SanchezPorras77, Kari Schirmer-Mikalsen76,78, Rico Frederik Schou79, Peter Smielewski19, Abayomi Sorinola80, Emmanuel Stamatakis35, Ewout W. Steyerberg54, 81, Nino Stocchetti82, Nina Sundström83, Riikka Takala84, Viktória Tamás80, Tomas Tamosuitis85, Olli Tenovuo66, Matt Thomas56, Dick Tibboel86, Christos Tolias87, Tony Trapani21, Cristina Maria Tudora61, Peter Vajkoczy88, Shirley Vallance21, Egils Valeinis 44, Zoltán Vámos38, Gregory Van der Steen31, Jeroen T.J.M. van Dijck64, Thomas A. van Essen64, Audrey Vanhaudenhuyse12,52, Roel P. J. van Wijk64, Alessia Vargiolu25, Emmanuel Vega53, Anne Vik78,89, Rimantas Vilcinis85, Victor Volovici46, Daphne Voormolen55, Petar Vulekovic34, Guy Williams35, Stefan Winzeck35, Stefan Wolf90, Alexander Younsi58, Frederick A. Zeiler35,91, Agate Ziverte44, Tommaso Zoerle20.

1Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Section of Perioperative Medicine and Intensive Care, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 2János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary; 3Division of Surgery and Clinical Neuroscience, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Oslo University Hospital and University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; 4Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway; 5Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway; 6Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospital Nancy, Nancy, France; 7Raymond Poincare hospital, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France; 8Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, S Raffaele University Hospital, Milan, Italy; 9Department of Neurosurgery, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; 10Department of Neurology, Neurological Intensive Care Unit, Medical University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria; 11Department of Neurosurgery & Anesthesia & intensive care medicine, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden; 12Anesthesie-Réanimation, Assistance Publique – Hopitaux de Paris, Paris, France; 13Department of Anesthesia & ICU, AOU Città della Salute e della Scienza di Torino - Orthopedic and Trauma Center, Torino, Italy; 14NeuroIntensive Care, Niguarda Hospital, Milan, Italy; 15Department of Neurology, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark ; 16Department of Public Health and Nursing, Faculty of Medicine and health Sciences, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway; 17Department of Surgery and Perioperative Science, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; 18Department of Neurosurgery, Medical School, University of Pécs, Hungary and Neurotrauma Research Group, János Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Hungary; 19Brain Physics Lab, Division of Neurosurgery, Dept of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK; 20Neuro ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy; 21ANZIC Research Centre, Monash University, Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; 22Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital of Cruces, Bilbao, Spain; 23Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain; 24School of Medicine and Surgery, Università Milano Bicocca, Milano, Italy; 25NeuroIntensive Care, ASST di Monza, Monza, Italy; 26Department of Anaesthesiology, University Hospital of Aachen, Aachen, Germany; 27Department of Anesthesia & Neurointensive Care, Cambridge University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK; 28School of Public Health & PM, Monash University and The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; 29Radiology/MRI department, MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge, UK; 30Intensive Care Unit, CHU Poitiers, Potiers, France; 31Department of Neurosurgery, Antwerp University Hospital and University of Antwerp, Edegem, Belgium; 32Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Maggiore Della Carità Hospital, Novara, Italy; 33Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium; 34Department of Neurosurgery, Clinical centre of Vojvodina, Faculty of Medicine, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia; 35Division of Anaesthesia, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK; 36Center for Stroke Research Berlin, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany; 37Intensive Care Unit, CHR Citadelle, Liège, Belgium; 38Department of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Therapy, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary; 39Departments of Neurology, Clinical Neurophysiology and Neuroanesthesiology, Region Hovedstaden Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark; 40Department of Neurology, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; 41Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive care, University Hospital Northern Norway, Tromso, Norway; 42Department of Neurosurgery, Hadassah-hebrew University Medical center, Jerusalem, Israel; 43Emergency Department, CHU, Liège, Belgium; 44Neurosurgery clinic, Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia; 45Department of Neurosurgery, Neurosciences Centre & JPN Apex trauma centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi-110029, India; 46Department of Neurosurgery, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands; 47Department of Neurosurgery, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway; 48Division of Neurosurgery, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, Addenbrooke’s Hospital & University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK; 49Neurointensive Care , Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield, UK; 50Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Neurosurgery, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; 51Hungarian Brain Research Program - Grant No. KTIA_13_NAP-A-II/8, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary; 52Cyclotron Research Center , University of Liège, Liège, Belgium; 53Department of Anesthesiology-Intensive Care, Lille University Hospital, Lille, France; 54Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospitals Southhampton NHS Trust, Southhampton, UK; 55Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical Center-University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 56Intensive Care Unit, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, Bristol, UK; 57Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care,M. Bufalini Hospital, Cesena, Italy; 58Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany; 59Department of Neurosurgery, The Walton centre NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool, UK; 60Karolinska Institutet, INCF International Neuroinformatics Coordinating Facility, Stockholm, Sweden; 61Department of Neurosurgery, Emergency County Hospital Timisoara , Timisoara, Romania; 62Department of Anesthesiology & Intensive Care, University Hospital of Grenoble, Grenoble, France; 63Department of Anesthesia & Intensive Care, Azienda Ospedaliera Università di Padova, Padova, Italy; 64Dept. of Neurosurgery, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands and Dept. of Neurosurgery, Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague, The Netherlands; 65Department of Neurosurgery, Helsinki University Central Hospital; 66Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Department of Neurosurgery and Turku Brain Injury Centre, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland; 67Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Pitié -Salpêtrière Teaching Hospital, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris and University Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France; 68Neurotraumatology and Neurosurgery Research Unit (UNINN), Vall d'Hebron Research Institute, Barcelona, Spain; 69Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of technology and Vilnius University, Vilnius, Lithuania; 70Department of Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain Medicine NHS Lothian & University of Edinburg, Edinburgh, UK; 71Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Oslo University Hospital/University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway; 72Division of Orthopedics, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway; 73Institute of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Olso, Oslo, Norway; 74National Trauma Research Institute, The Alfred Hospital, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia; 75Department of Neurosurgery, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; 76Department of Anasthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, St.Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway; 77Klinik für Neurochirurgie, Klinikum Ludwigsburg, Ludwigsburg, Germany; 78Department of Neuromedicine and Movement Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NTNU, Trondheim, Norway; 79Department of Neuroanesthesia and Neurointensive Care, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; 80Department of Neurosurgery, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary ; 81Dept. of Department of Biomedical Data Sciences, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands ; 82Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Milan University, and Neuroscience ICU, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milano, Italy; 83Department of Radiation Sciences, Biomedical Engineering, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden; 84Perioperative Services, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Management, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland; 85Department of Neurosurgery, Kaunas University of Health Sciences, Kaunas, Lithuania; 86Intensive Care and Department of Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus Medical Center, Sophia Children’s Hospital, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; 87Department of Neurosurgery, Kings college London, London, UK; 88Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany; 89Department of Neurosurgery, St.Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway; 90Department of Neurosurgery, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, corporate member of Freie Universität Berlin, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, and Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany; 91Section of Neurosurgery, Department of Surgery, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada.

Funding

This research is funded by the European Commission 7th Framework program (602150). The funder had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

JH and AD analyzed the data. JH drafted the tables and figures. AD made supplemental Fig. 6. JH, AD, AE, and DM interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. AE designed the study protocol and supervised the study. AD and DM were involved in regular meetings on the manuscript and reviewed the manuscript multiple times. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In each recruiting site ethical approval was given; an overview is available online (https://www.center-tbi.eu/project/ethical-approval).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AIRM declares consulting fees from PresSura Neuro, Integra Life Sciences, and NeuroTrauma Sciences. DKM reports grants from the UK National Institute for Health Research, during the conduct of the study; grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline; personal fees from Neurotrauma Sciences, Lantmaanen AB, Pressura, and Pfizer, outside of the submitted work. WP reports grants from the Netherlands Brain Foundation. ES reports personal fees from Springer, during the conduct of the study. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Therapy Intensity Level scale. Description: This table shows the scoring of the Therapy Intensity Level (TIL) as recorded in the CENTER-TBI study. Derived from Zuercher et al. [3]. High TIL therapies are shown in bold.

Additional file 2.

Missing data. Description: This figure shows the proportion of missing data in the original data (before imputation). In the left panel the proportion of missingness per variable is shown. In the combination plot (grid) all patterns of missing (red) and observed data (blue) are shown. For example, the bottom row shows all patients with complete data, above that the patients with the combination missing data for Hb and gluc, ect. The bars on the right of the combination plot show the frequency of occurrence of the combinations.

Additional file 3.

Treatments on the TIL scale (all patients).Description: This table shows the number and percentages of ICP-monitored patients receiving ICP-lowering treatments on the TIL scale. Each row shows the number of patients (frequency) that receive that treatment (a patient could receive multiple treatments per topic).

Additional file 4.

Daily TIL scores. Description: This figure shows the daily high TIL scores (cumulative score of the high TIL treatments) plotted against the daily low TIL scores (cumulative score for low TIL treatments). It shows that at the same high TIL scores a variety of low TIL treatment (scores) is applied (in some cases even no low TIL treatment). Also, the figure shows mainly at day 3 (dark green) higher TIL treatments are applied including higher low TIL scores.

Additional file 5.

Treatments on the TIL scale (high TIL patients). Description: This table shows the number and percentages of high TIL patients receiving ICP-lowering treatments on the TIL scale. Each row shows the number of patients (frequency) that receive that treatment (a patient could receive multiple treatments per topic) Bolt treatment are regarded as high TIL treatment.

Additional file 6.

Higher tier ICP-lowering treatments in patients receiving high TIL treatment. Description: This figure shows the proportion of patients that receive first and second tier treatments of the high TIL patients across 7 days at the Intensive Care Unit.

Additional file 7.

Variation in high TIL treatment percentages across centres (centre-level). Description: This table describes the between-centre variation for high TIL treatments across the days. The number of centres are the centres that actually apply the individual treatments. The mean percentage represents the mean percentage of patients across centres that receive the therapy, while the IQR and min-max represents the variation in treatment use between centres.

Additional file 8.

Baseline characteristics matched dataset. Description: This table describes the baseline characteristics of the matched cases with complete data (as the dataset was imputed, this table could only be completed for complete cases). Significant group differences were determined by using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test (non-normal distributions) for categorical variables and an ANOVA or Kruskal Wallis test (non-normal distributions) for continuous variables.

Additional file 9.

Maximum ICP values prior to start high TIL use per treatment group. Description: This figure shows the differences in maximum ICP values prior to high TIL treatment between patients with a high TIL (1) versus a low TIL treatment (0). The median ICP for low TIL is 22 [16-28] and for high TIL 22 [16-27]. This difference is not statistically significant.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huijben, J.A., Dixit, A., Stocchetti, N. et al. Use and impact of high intensity treatments in patients with traumatic brain injury across Europe: a CENTER-TBI analysis. Crit Care 25, 78 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03370-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03370-y