Abstract

Background

There is no information on the impact of donor type in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT) using homogeneous graft-versus-host (GVHD) prophylaxis with post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy) in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed outcomes of adult patients with ALL in CR1 that had received HCT with PTCy as GVHD prophylaxis from HLA-matched sibling (MSD) (n = 78), matched unrelated (MUD) (n = 94) and haploidentical family (Haplo) (n = 297) donors registered in the EBMT database between 2010 and 2018. The median follow-up period of the entire cohort was 2.2 years.

Results

Median age of patients was 38 years (range 18–76). Compared to MSD and MUD, Haplo patients received peripheral blood less frequently. For Haplo, MUD, and MSD, the cumulative incidence of 100-day acute GVHD grade II–IV and III–IV, and 2-year chronic and extensive chronic GVHD were 32%, 41%, and 34% (p = 0.4); 13%, 15%, and 15% (p = 0.8); 35%, 50%, and 42% (p = 0.01); and 11%, 17%, and 21% (p = 0.2), respectively. At 2 years, the cumulative incidence of relapse and non-relapse mortality was 20%, 20%, and 28% (p = 0.8); and 21%, 18%, and 21% (p = 0.8) for Haplo, MUD, and MSD, respectively. The leukemia-free survival, overall survival and GVHD-free, relapse-free survival for Haplo, MUD, and MSD was 59%, 62%, and 51% (p = 0.8); 66%, 69%, and 62% (p = 0.8); and 46%, 44%, and 35% (p = 0.9), respectively. On multivariable analysis, transplant outcomes did not differ significantly between donor types. TBI-based conditioning was associated with better LFS.

Conclusions

Donor type did not significantly affect transplant outcome in patient with ALL receiving SCT with PTCy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The role of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (alloHCT) in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has recently been critically evaluated in two systematic evidence-based reviews, one by the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT) [1] and the other by the European Working Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (EWALL) and the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) [2]. Both documents state that alloHCT is considered the best option for adult patients with ALL in first complete remission (CR1) with high-risk features. In addition, there was a consensus in considering that the preferred donor in this setting is an HLA-matched sibling donor (MSD) or matched unrelated donor (MUD). For patients with ALL in need of alloHCT lacking an HLA-matched donor, alternative donor options such as a haploidentical family donor (Haplo), mismatched unrelated donor (MMUD), and unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation can be considered [3,4,5,6].

A few recent studies of adult patients with high-risk ALL undergoing haploidentical HCT have reported favorable transplant outcomes, which has led to the consideration of this approach as a valid option for patients lacking a matched donor [4, 5, 7,8,9,10]. In patients with this disease undergoing haploidentical HCT, post-transplant cyclophosphamide (PTCy), in the absence of prospective randomized data, may be considered over ATG [10]. There has been increased interest of comparing haploidentical HCT with other stem cell donors. Indeed, two recent studies of the ALWP of the EBMT comparing transplant outcomes in patients with ALL who underwent haploidentical and MUD transplant showed comparable results [4, 5]. One of them analyzed patients in CR1 using PTCy- and ATG-based GVHD prophylaxis [5], while the other is a joint study of the EBMT with the Transplant and Cellular Therapy–Research Consortium (TCT-RC) [4], in which they performed a matched-pair comparison in patients who underwent haploidentical HCT with PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis and MUD transplant [5]. In a latest multicenter biologically phase III randomized study, Wang et al. [7] showed comparable outcomes in patients with ALL in CR1 who received alloHCT from MSD or haploidentical donor using an ATG-based strategy. Very recently we compared haploidentical HCT to alloHCST from MSD in patients with ALL in CR demonstrating higher relapse rates while lower transplant-related mortality in the MSD transplants [11]. However, as far as we know, none of these studies compared outcomes of haploidentical HCT with both alloHCT from MSD or MUD using a homogeneous PTCy-based GVHD prophylaxis in patients with ALL in CR1.

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of donor type on the outcome of patients with ALL in CR1 undergoing unmanipulated alloHCT using PTCy as GvHD prophylaxis. We analyzed patients who had received alloHCT from MSD, MUD and Haplo family donors, reported to the EBMT registry between 2010 and 2018.

Patients and methods

Study design and data source

This is a retrospective registry-based analysis on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the EBMT. The EBMT is a voluntary working group of more than 600 transplantation centers that are required to report all consecutive stem cell transplantations and follow-up once a year. In EBMT registry, there is an internal quality control regarding accuracy and consistency of what is entered data and periodic queries on missing / incorrect data and follow-up requests. A routinely audit, however, will not be performed. All transplantation centers are required to obtain written informed consent before data registration with the EBMT in accordance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient eligibility

All adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with ALL in CR1 at transplantation, registered in the EBMT ProMISe database, who underwent a first alloHCT from an unmanipulated graft, using PTCy from Haplo, MUD or MSD donors between 2010 and 2018 were eligible. MUD was defined as 10/10 patient and donor compatibility considering HLA A, B, C, and DRB1 and DQB1 allelic typing. Haplo transplant was defined as one with the number of donor–recipient human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches ≥ 2.

Endpoints and definitions

The primary endpoint was leukemia-free survival (LFS) after MSD, MUD, and Haplo donor transplants. Secondary endpoints were neutrophil engraftment, acute GVHD (aGVHD) and chronic GVHD (cGVHD), relapse incidence, non-relapse mortality (NRM), GVHD-free, relapse-free survival (GRFS), and overall survival (OS) within the same subgroups and to perform analysis of risk factors for each outcome.

Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first day of an absolute neutrophil count of 0.5 × 109/L lasting for ≥ 3 consecutive days. Acute GVHD and cGVHD were defined and graded according to standard criteria [12, 13]. Relapse was defined as disease recurrence and appearance of blasts in the peripheral blood (PB) or bone marrow (> 5%) after CR. LFS was calculated until the date of first relapse, death from any cause, or the last follow-up. NRM was defined as death from any cause other than relapse. The composite endpoint GRFS was defined as survival without the following events: stage III–IV aGVHD, severe cGVHD, disease relapse, or death from any cause after SCT [14]. Myeloablative conditioning (MAC) was defined as a regimen containing either total body irradiation (TBI) with a dose > 6 Gray, a total dose of oral busulfan > 8 mg/kg, or a total dose of intravenous busulfan > 6.4 mg/kg [15]. All other regimen intensities were defined as reported by the centers.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics according to donor type were compared using the chi-square test for categorical and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. GRFS, LFS, and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Cumulative incidence functions were used to estimate neutrophil engraftment, aGVHD, cGVHD, relapse incidence, and NRM. Competing risks were death for relapse incidence and neutrophil engraftment, relapse for NRM, relapse or death for aGVHD and cGVHD. Univariate analyses were performed using the log-rank test for LFS, GRFS, and OS, and Gray’s test for cumulative incidence. Multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional-hazards model [16].

Donor type, gender, age at transplantation, Karnofsky performance status, transplantation year, patient cytomegalovirus serostatus, use of TBI, and type of ALL (using the Phi positivity) were included in the final model. The missing data on Ph positivity were handled as a supplementary category in multivariate models for adjustment. Stem cell source and use of ATG were not included in the model due to their association with donor type. TBI was used over conditioning intensity due to low numbers of TBI-based RIC in MSD (n = 13) and MUD (n = 12). To allow the center effect, we introduced a random effect (frailty term) for each center into the model. Median follow-up was estimated using the reverse Kaplan–Meier method. The significance level was fixed at 0.05, and P values were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.2 (R Development Core Team, Vienna, Austria) software packages.

Results

Patient and transplantation characteristics

Patient, disease, and transplant characteristics of the overall study population and according to donor type are summarized in Table 1. A total of 469 patients were included in the study, of which 297 were transplanted from Haplo, 94 from MUD and 78 from MSD donors. The median age of patients was 37 years (range 18–76) and 64% were male. ALL was of B-cell origin in 359 (77%) patients and 166 (41%) were Ph positive, 243 (59%) Ph negative (including all T-cell types) and the Ph data was missing for 60 patients. PB was used as the stem cell source in 293 (62%) patients. Regarding conditioning, 209 (45%) were TBI-based regimens and 387 (83%) patients received MAC. PTCy was used alone in (n = 27; 6%) or in combination with 1 (n = 75; 16%) or 2 (n = 367; 78%) immunosuppressive drugs. Most frequent immunosuppressive drugs associated with PTCy were: combination of mycophenolate mofetil and calcineurin inhibitors (n = 318; 68%), calcineurin inhibitors alone (n = 44; 9%), methotrexate with (n = 29; 6%) or without cyclosporine (n = 17; 4%), and combination of mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus (n = 14; 3%). In vivo T-cell depletion (TCD), mainly ATG, was used in 58 (12%) patients, 23 (8%) in Haplo, 13 (17%) in MSD and 22 (23%) in MUD.

MSD, MUD, and Haplo recipients did not differ with respect to patient and disease characteristics. Regarding transplant characteristics, Haplo patients less frequently received TCD (p < 0.001) and PB (p < 0.001). Although most (92%) Haplo patients received GvHD prophylaxis with PTCy combined with two other immunosuppressive drugs, only 73% and 32% of MUD and MSD patients, respectively, received such a combination (p < 0.001).

Median follow-up was 2.2 years (95% CI 2–2.8) for the entire cohort, 2.6 years (95% CI 2.1–3) for Haplo, 1.9 years (95% CI 1.2–2.8) for MUD, and 2 years (95% CI 1.4–3) for MSD patients.

Engraftment, acute and chronic GVHD

The cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery at 60 days was 97% (95% CI 94–98) for Haplo, 100% for MUD, and 99% (95% CI 85–100) for MSD (p = 0.23). The median time to neutrophil recovery was the same at 18 days (interquartile range [IQR] 15–20), 18 days (IQR 14–21), and 18 days (IQR 14–20) for Haplo, MUD and MSD, respectively.

The cumulative incidence of aGvHD grade II–IV at 100 days was 32% (95% CI 27–38) for Haplo, 41% (95% CI 30–51) for MUD, and 34% (95% CI 23–45) for MSD (p = 0.4). The 100-day cumulative incidence of aGVHD grade III–IV was 13% (95% CI 9–17) for Haplo, 15% (95% CI 9–24) for MUD, and 15% (95% CI 8–24) for MSD (p = 0.8) (Table 2). On multivariable analysis, no variables were found to have a significant impact on the risk of aGvHD (Tables 3 and 4).

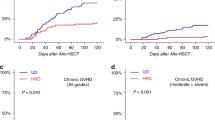

The 2-year cumulative incidence of cGVHD was 35% (95% CI 29–41), 50% (95% CI 37–61), and 42% (95% CI 29–54) (p = 0.01) for Haplo, MUD, and MSD, respectively (Table 2). The cumulative incidence of extensive cGVHD was 11% (95% CI 7–15) for Haplo, 17% (95% CI 9–27) for MUD, and 21% (95% CI 12–33) for MSD (p = 0.2) (Table 2). On multivariable analysis (Table 3), MUD showed an increased risk of cGVHD when compared with MSD (hazard ratio [HR] 1.84; 95% CI 1.02–3.34; p = 0.04). Other factors associated with a lower risk of cGVHD were female gender (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.4–0.87; p = 0.008), and transplant performed more recently (HR 0.9; 95% CI 0.81–0.99; p = 0.03) (Table 4).

Relapse

The median time to relapse was 7 months (IQR 4–14). The cumulative incidence of relapse at 2 years was not significantly different across the donor types with 20% (95% CI 16–26) for Haplo, 20% (95% CI 12–30) for MUD, and 28% (95% CI 17–41) for MSD (p = 0.8) (Table 2) (Fig. 1). On multivariable analysis, Ph + patients had a lower risk of relapse (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.32–0.9; p = 0.02) (Table 4).

NRM and causes of death

The cumulative incidence of NRM at 2 years was 21% (95% CI 17–26) for Haplo, 18% (95% CI 10–27) for MUD, and 21% (95% CI 12–32) for MSD (p = 0.8) (Table 2) (Fig. 2). In multivariable analysis higher recipient’s age per 10 years (HR 1.3; 95% CI 1.1–1.55; p = 0.002) was the only factor significantly associated with an increased NRM (Table 4).

At last follow-up, 151 patients had died, of which 90 (60%) were due to a variety of non-relapse causes, 61 (60%) in Haplo, 15 (60%) in MUD, and 14 (58%) in MSD. The main causes of transplant-related deaths were infections and GvHD, being 25 (25%) and 16 (16%) in Haplo, 8 (32%) and 3 (12%) in MUD, and 4 (17%) and 6 (25%) in MSD cohorts, respectively (Table 5).

Survival outcomes

For the entire cohort, LFS, OS, and GRFS at 2 years were 58% (95% CI 53–63), 66% (95% CI 61–71), and 44% (95% CI 39–49), respectively.

LFS was 59% for Haplo, 62% for MUD, and 51% for MSD (p = 0.8) (Table 2) (Fig. 3). On multivariate analysis, the use of TBI was associated with better LFS (HR 0.7; 95% CI 0.51–0.98; p = 0.04) (Table 4).

OS did not differ significantly with 66% for Haplo, 69% for MUD, and 62% for MSD (p = 0.8) (Table 2) (Fig. 4). On multivariate analysis, female gender (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.47–1; p = 0.048) and transplants performed more recently (HR 0.9; 95% CI 0.82–0.98; p = 0.01) were associated with better OS, while higher recipient age per 10 years was associated with a worse OS (HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.02–1.31; p = 0.03) (Table 4).

GRFS was 46%, 44%, and 35% for Haplo, MUD, and MSD, respectively (p = 0.9) (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, female gender was associated with better GRFS (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.56–0.99; p = 0.04) (Table 4).

Discussion

This study shows that transplant outcomes in terms of NRM, relapse, and survival probabilities in patients with ALL in CR1 undergoing alloHCT were not significantly different according to donor type. This study provides evidence to support Haplo transplantation as a valuable alternative donor option in this setting when a matched donor is not available. Our results also show that the use of PTCy for GvHD prophylaxis in patients with ALL in CR1 receiving HCT from MSD, MUD and Haplo is safe and effective, resulting in low cumulative incidences of GVHD, especially cGVHD, in all transplant settings. Nevertheless, alloHCT from MUD had a significant increased risk of cGVHD than those from MSD and Haplo. In accordance to many previous publications TBI-based conditioning was associated with better LFS.

This study confirmed that PTCy was highly effective in preventing acute and chronic extensive GvHD in MSD, MUD, and Haplo HCT and seems to compare favorably with standard GvHD prophylaxis with a calcineurin inhibitor and methotrexate in MSD and MUD transplants [17, 18]. In fact, the incidence of GvHD after PTCy seems similar to that reported with ATG in both matched donor settings [19, 20]. The incidence of severe aGVHD in the Haplo HCT in our study (13%) was similar to that previously reported with PTCy [10, 21, 22], but higher than that reported by Wang et al. with ATG-based prophylaxis (6%) [7]. This may be explained by differences in variables such as age, conditioning regimens and stem cell source, among others. Interestingly, we observed no significant differences in the cumulative incidence of grade II–IV and III–IV aGVHD in ALL according to donor type, as observed in previous studies [4].

The present study did not find statistically significant differences in extensive cGVHD between the three cohorts in univariate analysis. However, the low incidence of this in all cohorts, but especially in the Haplo cohort (11%), deserves to be noted. As recently demonstrated by the ALWP-EBMT, the addition of immunosuppressive drugs to PTCy enhances its effect and reduces the risk of severe cGVHD, reducing mortality and improving survival [23, 24]. The influence of stem cell source was also relevant, as almost 50% of the patients in the Haplo group received BM. The use of BM seems to lower the risk of cGVHD in haplo setting [25]. In addition, recent studies have observed lower GVHD in patients receiving BM haploidentical transplants compared to PB MUD transplants [26].

In contrast to what was observed in patients with AML in CR1 transplanted under a similar prophylaxis of GVHD, in whom a significantly higher rate of NRM and a lower rate of relapse were found in the haploidentical setting compared to MSD and MUD [26], the present study in patients with ALL in CR1 could not detect any difference in these outcomes between the three groups. The lack of significant differences in NRM and relapse translated into an absence of significant differences between the three cohorts not only in OS and LFS, but also in GRFS. All these outcomes are in line with those reported in other studies analyzing patients with ALL in CR1 [5, 7, 8]. In the two comparative studies, as in ours, there were also no statistically differences in NRM, relapse, OS, LFS, and GRFS between alloHCT from haploidentical donor compared with MSD using ATG [26] or with MUD using PTCy or ATG [5]. In a subgroup analysis of patients in CR1 from another comparative study that included patients in all stages of the disease, no differences were also observed for these outcomes when the haploidentical receptors and MUD were compared [4].

The 2-year relapse incidence of 20% in the haploidentical cohort is in line with that reported in other studies analyzing patients with ALL in CR1 [7, 8]. The PTCy strategy seems to offer a good balance between GVHD prevention and antileukemic efficacy. Interestingly, a recent ALWP-EBMT study comparing PTCy with ATG in haploidentical HCT for ALL showed reduced relapse risk with PTCy [10]. Relapse rate was particularly low in Ph + patients, for which excellent results using universal PTCy strategy have been recently described [27]. Although we did not have data on the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in this study, it is likely that their use pre- and post-transplant may have contributed to the low relapse rate.

We should emphasize that the use of TBI was the only factor identified in the multivariate analysis associated with a better LFS. Although the advantage of TBI over chemotherapy in ALL has never been prospectively analyzed, a few meta-analysis [28, 29] and retrospective studies [30, 31] have previously suggested this advantage of TBI in adults with ALL.

Due to the retrospective nature of a registry-based study, some potential bias cannot be ruled out. To avoid an important source of bias, the analysis was restricted to patients with ALL in CR1 and those using PTCy as GVHD prophylaxis. However, a variety of conditioning regimens were used and there were obvious differences in the stem cell source and GvHD prevention strategies, such as in vivo TCD or the addition of other immunosuppressive drugs, depending on the type of donor. In fact, patients undergoing HCT from MSD and MUD more frequently received PB and in vivo TCD than did Haplo transplant recipients. Although some of these factors could be adjusted for in multivariable analysis, cell sources, TCD, and combination of immunosuppressive drugs for GvHD prophylaxis were strongly associated with type of donor and their effect could not be evaluated. Therefore, the results of this study should be interpreted in the context of these different transplant packages that include donor type together with stem cell source, TCD and GVHD prophylaxis strategies. In addition, important variables such as pre-transplant minimal residual disease and comorbidity index were not available. Despite the heterogeneity in these factors, the analysis of a large series of patients limited to an early stage of a single disease (ALL in CR1) who used a homogeneous GvHD prophylaxis with PTCy, allowed us to segregate the effect of donor from the effect of GvHD prophylaxis. Future studies, like the ongoing European prospective randomized study comparing MUD to Haplo (Haplo-MUD Study) with PTCy in both arm (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04232241), will be able to overcome some of these limitations.

Conclusions

In patients with ALL undergoing allo-SCT, PTCy for GVHD prophylaxis seems promising and should be compared prospectively to standard regimens in order to establish the standard of care. In this scenario, under homogeneous GVHD prophylaxis, transplant outcomes with different donor types were similar, providing evidence to support Haplo transplantation as a valuable alternative donor option in this setting.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the ALWP of EBMT in Paris, Saint Antoine Hospital.

Abbreviations

- aGVHD:

-

Acute GVHD

- allo-SCT:

-

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

- ALWP:

-

Acute Leukemia Working Party

- ALL:

-

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- BM:

-

Bone marrow

- cGVHD:

-

Chronic GVHD

- CR1:

-

First complete remission

- EBMT:

-

European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation

- GRFS:

-

GVHD-free and relapse-free survival

- GVHD:

-

Graft-versus-host

- Haplo:

-

Haploidentical donors

- HLA:

-

Human leukocyte antigen

- LFS:

-

Leukemia-free survival

- MAC:

-

Myeloablative conditioning

- MSD:

-

Matched sibling donors

- MUD:

-

Matched unrelated

- NRM:

-

Nonrelapse mortality

- PB:

-

Peripheral blood

- PTCy:

-

Post-transplant cyclophosphamide

- RIC:

-

Reduced intensity conditioning

- SCT:

-

Stem cell transplantation

- OS:

-

Overall survival

References

DeFilipp Z, Advani AS, Bachanova V, Cassaday RD, Deangelo DJ, Kebriaei P, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation in the treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: updated 2019 evidence-based review from the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25:2113–23.

Giebel S, Marks DI, Boissel N, Baron F, Chiaretti S, Ciceri F, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission: a position statement of the European Working Group for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (EWALL) and the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2019;54:798–809.

Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Sanz G, Piemontese S, Arcese W, Bacigalupo A, et al. Comparison of outcomes after unrelated cord blood and unmanipulated haploidentical stem cell transplantation in adults with acute leukemia. Leukemia. 2015;29:1891–900.

Malki Al MM, Yang D, Labopin M, Afanasyev B, Angelucci E, Bashey A, et al. Comparing transplant outcomes in ALL patients after haploidentical with PTCy or matched unrelated donor transplantation. Blood Adv. 2020;4:2073–83.

Shem-Tov N, Peczynski C, Labopin M, Itälä-Remes M, Blaise D, Labussière-Wallet H, et al. Haploidentical vs. unrelated allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission: on behalf of the ALWP of the EBMT. Leukemia. 2020;34:283–92.

Brissot E, Labopin M, Russo D, Martin S, Schmid C, Glass B, et al. Alternative donors provide comparable results to matched unrelated donors in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation in second complete remission: a report from the EBMT Acute Leukemia Wsorking Party. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:1763–72.

Wang Y, Liu Q-F, Xu L-P, Liu K-Y, Zhang X-H, Ma X, et al. Haploidentical versus matched-sibling transplant in adults with philadelphia-negative high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a biologically phase III randomized study. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3467–76.

Santoro N, Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Bacigalupo A, Ciceri F, Gülbas Z, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical stem cell transplantation in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a study on behalf of the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. J Hematol Oncol BioMed Central. 2017;10:113–211.

Srour SA, Milton DR, Bashey A, Karduss-Urueta A, Malki Al MM, Romee R, et al. Haploidentical transplantation with post-transplantation cyclophosphamide for high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:318–24.

Nagler A, Kanate AS, Labopin M, Ciceri F, Angelucci E, Koc Y, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus anti-thymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prevention in haploidentical transplantation for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2020.247296.

Nagler A, Labopin M, Houhou AM, Mousavi A, Hamladji RM, et al. Outcome of haploidentical versus matched sibling donors in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:53.

Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18:295–304.

Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, Klingemann HG, Beatty P, Hows J, et al. 1994 Consensus conference on acute GVHD grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–8.

Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Ciceri F, Mohty M, Nagler A. Definition of GvHD-free, relapse-free survival for registry-based studies: an ALWP-EBMT analysis on patients with AML in remission. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2016;51:610–1.

Spyridonidis A, Labopin M, Savani BN, Niittyvuopio R, Blaise D, Craddock C, et al. Redefining and measuring transplant conditioning intensity in current era: a study in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:1114–25.

Kanate AS, Nagler A, Savani B. Summary of scientific and statistical methods, study endpoints and definitions for observational and registry-based studies in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clin Hematol Int. 2019;2:2–4.

Tegla C, Choi J, Abdul-Hay M, Cirrone F, Cole K, Al-Homsi AS. Current status and future directions in graft-versus-host disease prevention following allogeneic blood and marrow transplantation in adults. Clin Hematol Int. 2020;2:5–12.

Yakoub-Agha I, Mesnil F, Kuentz M, Boiron JM, Ifrah N, Milpied N, et al. Allogeneic marrow stem-cell transplantation from human leukocyte antigen-identical siblings versus human leukocyte antigen-allelic-matched unrelated donors (10/10) in patients with standard-risk hematologic malignancy: a prospective study from the French Society of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Cell Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5695–702.

Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:855–64.

Kröger N, Solano C, Wolschke C, Bandini G, Patriarca F, Pini M, et al. Antilymphocyte globulin for prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:43–53.

Bacigalupo A, Dominietto A, Ghiso A, Di Grazia C, Lamparelli T, Gualandi F, et al. Unmanipulated haploidentical bone marrow transplantation and post-transplant cyclophosphamide for hematologic malignanices following a myeloablative conditioning: an update. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2015;50(Suppl 2):S37–9.

Ruggeri A, Sun Y, Labopin M, Bacigalupo A, Lorentino F, Arcese W, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide versus anti-thymocyte globulin as graft- versus-host disease prophylaxis in haploidentical transplant. Haematologica. 2017;102:401–10.

Cytryn S, Abdul-Hay M. Haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation followed by “post-cyclophosphamide”: the future of allogeneic stem cell transplant. Clin Hematol Int. 2020;2:49–58.

Ruggeri A, Labopin M, Bacigalupo A, Afanasyev B, Cornelissen JJ, Elmaagacli A, et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in HLA matched sibling or matched unrelated donor transplant for patients with acute leukemia, on behalf of ALWP-EBMT. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:40.

Im A, Rashidi A, Wang T, Hemmer M, MacMillan ML, Pidala J, et al. Risk factors for graft-versus-host disease in haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation using post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2020;26:1459–68.

Nagler A, Labopin M, Dholaria B, Angelucci E, Afanasyev B, Cornelissen JJ, et al. Comparison of haploidentical bone marrow versus matched unrelated donor peripheral blood stem cell transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide in patients with acute leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:843–51.

Webster JA, Luznik L, Tsai H-L, Imus PH, Dezern AE, Pratz KW, et al. Allogeneic transplantation for Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia with posttransplantation cyclophosphamide. Blood Adv. 2020;4:5078–88.

Shi-xia X, Xian-hua T, Hai-qin X, Bo F, Xiang-Feng T. Total body irradiation plus cyclophosphamide versus busulphan with cyclophosphamide as conditioning regimen for patients with leukemia undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a meta-analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51:50–60.

Gupta T, Kannan S, Dantkale V, Laskar S. Cyclophosphamide plus total body irradiation compared with busulfan plus cyclophosphamide as a conditioning regimen prior to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2011;4:17–29.

Eroglu C, Pala C, Kaynar L, Yaray K, Aksozen MT, Bankir M, et al. Comparison of total body irradiation plus cyclophosphamide with busulfan plus cyclophosphamide as conditioning regimens in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54:2474–9.

Kebriaei P, Anasetti C, Zhang M-J, Wang H-L, Aldoss I, de Lima M, et al. Intravenous busulfan compared with total body irradiation pretransplant conditioning for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2018;24:726–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Emmanuelle Polge from the office of the ALWP of the EBMT for data collection. This work is dedicated to the memory of Dr Boris Afanasyev, pioneer of stem cell transplantation in Russia and important contributor to the present study who died on March 16, 2020.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS, AN, and MM designed the study. J-EG performed the statistical analysis. ML helped with the interpretation of the results. JS wrote the manuscript. BA, EA, NK, YK, FC, JLD, MA, SS, MR, MA, and JT provided patients for the study, BS and AR participated to study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The scientific board of the ALWP of EBMT approved this study. All patients gave written informed consent for the use of their data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable for individual patient data. This is a pooled analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sanz, J., Galimard, JE., Labopin, M. et al. Post-transplant cyclophosphamide containing regimens after matched sibling, matched unrelated and haploidentical donor transplants in patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission, a comparative study of the ALWP of the EBMT. J Hematol Oncol 14, 84 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01094-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-021-01094-2