Abstract

Background

Jumping translocations (JTs) are rare chromosome rearrangements characterized by re-localization of one donor chromosome to multiple recipient chromosomes. Here, we describe an acute myeloid leukemia (AML) that progressed from myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) in association with acquisition of 1q JTs. The sequence of molecular and cytogenetic changes in our patient may provide a mechanistic model for the generation of JTs in leukemia.

Case presentation

A 68-year-old man presented with pancytopenia. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed a hypercellular marrow with multilineage dysplasia, consistent with MDS, with no increase in blasts. Karyotype and MDS fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) panel were normal. Repeat bone marrow aspirate and biopsy after 8 cycles of azacitidine, with persistent pancytopenia, showed no changes in morphology, and karyotype was again normal. Myeloid mutation panel showed mutations in RUNX1, SRSF2, ASXL1, and TET2. Three years after diagnosis, he developed AML with myelodysplasia-related changes. Karyotype was abnormal, with unbalanced 1q JTs to the short arms of acrocentric chromosomes 14 and 21, leading to gain of 1q.

Conclusions

Our patient had MDS with pathogenic mutations of the RUNX1, SRSF2, ASXL1, and TET2 genes and developed 1q JTs at the time of progression from MDS to AML. Our data suggest that the formation of 1q JTs involves multiple stages and may provide a mechanistic model for the generation of JTs in leukemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Jumping translocations (JTs) are chromosomal rearrangements comprising one donor chromosome and multiple recipient chromosomes [1]. Although JTs have been reported in neoplasms and constitutional chromosome abnormalities, they are rare chromosome rearrangements in neoplastic diseases. JTs are characterized by translocations of one donor chromosome to various recipient chromosomes, resulting in several gains of this chromosomal segment and possible loss of segments of the recipient chromosomes [1, 2]. Fusion of the break-off donor chromosome segment to telomeric or interstitial regions of recipient chromosomes can form different chromosomal patterns of jumping translocations. Jumping translocations involving 1q12–21 as the donor chromosome segment, referred to as jumping translocations of 1q (1q JTs), are nonrandomly involved in multiple myeloma and malignant lymphoproliferative disorders [3, 4]. 1q JTs have been described infrequently in patients with myeloid malignancies and have been associated with a high risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukemia (AML), resistance to chemotherapy and poor survival rates [5, 6].

While several mechanisms have been proposed to explain JT formation, including viral infection, chromosome instability, pericentromeric heterochromatin de-condensation, shortened telomeres, and illegitimate recombination between telomere repeat sequences and interstitial telomeric sequences [3, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13], the mechanism of 1q JT formation in patients with myeloid malignancies is still not fully understood. Here, we describe a patient with AML that progressed from a myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with pathogenic mutations of the RUNX1, SRSF2, ASXL1, and TET2 genes in association with development of 1q JTs, which supports that the formation of 1q JTs may involve multiple stages and that 1q JTs may represent a very high-risk cytogenetic abnormality with transformation to AML.

Case presentation

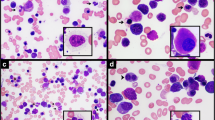

A 68-year-old man presented with pancytopenia. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy showed a hypercellular marrow (90%) with multilineage dysplasia, consistent with MDS, with no increase in blasts. Karyotype and MDS fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) panel were normal. Repeat bone marrow aspirate and biopsy after 8 cycles of azacitidine, with persistent pancytopenia, showed no changes in morphology, and karyotype was again normal. Myeloid mutation panel showed mutations in RUNX1 (Glu223Glyfs*16), SRSF2 (Pro95His), ASXL1 (Gln976*), and TET2 (Ser890*) (TruSight myeloid sequencing panel, Illumina, Inc.). He received several other unsuccessful therapies, with serial bone marrow testing showing no change in morphology, a normal karyotype, and no change in myeloid mutations. Three years after diagnosis, his white blood cell count increased rapidly to 36.9 K/mcL with 20% blasts (Fig. 1a). Bone marrow biopsy (Fig. 1b) and aspirate (Fig. 1c) were hypercellular (80%) with increased reticulin fibrosis (Grade 2–3/3) and with 53% myeloblasts by aspirate differential, diagnostic of AML with myelodysplasia-related changes. Karyotype was abnormal, with unbalanced 1q JTs: 46,XY,+ 1,der(1;21)(p10 or q10;q10) [7]/46,XY,+ 1, der(1;14)(p10 or q10;q10),i(18)(q10) [5]/46,XY,+ 1,del(1)(p12, 1]/46,XY [8] (Fig. 1d). FISH analyses of prior bone marrow biopsies, including one obtained less than a month prior to transformation to AML, did not show 1q JTs. A week later, the patient presented to the emergency department after a fall, became obtunded, and was diagnosed with necrotizing subdural abscess and bacteremia. He was transitioned to comfort care and passed away the next day.

a Peripheral blood shows marked leukocytosis with numerous blasts and promyelocytes, dyspoietic granulocytes with nuclear hypolobation and hypogranularity, and dyspoietic erythroid precursors. b Bone marrow core biopsy is hypercellular for age (80%). Maturing granulopoiesis and erythropoiesis are replaced by sheets of immature cells. Megakaryocytes are decreased and have atypical morphology. c Bone marrow aspirate consists of blasts which are intermediate in size with fine chromatin, prominent nucleoli and scant basophilic cytoplasm. A few dyspoietic maturing granulocytes and atypical megakaryocytes are present. d Partial karyograms of a 46,XY,+ 1,der(1;21)(p10 or q10;q10) karyotype, a 46,XY,+ 1,del(1)(p12) karyotype, and 46,XY,+ 1,der(1;14)(p10 or q10;q10),i(18)(q10) karyotype. e Whole-genome SNP microarray shows mosaic gain of chromosome 1 from 1p11 to 1qter regions and mosaic gain of chromosome 18q. f Fusion sites of recipient chromosomes of 149 jumping translocations of 1q in 48 myeloid neoplasm patients (including our patient). g A possible multi-stage process for the development and formation of 1q JTs in our patient.

Characterization of the 1q JTs in our patient

Whole-genome single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) microarray showed mosaic gain of chromosomes 1p11-1q44 and 18q11.1-18q23, arr [hg19] 1p11q44(120,365,518_ 249,224,684)× 2–3,18q11.1q23(18, 811,960_78,014,123)× 2–3 (Fig. 1e). The 1q JTs were demonstrated to have a chromosome 1 centromere using a centromere 1 Satellite II/III FISH probe (Abbott/Vysis, Inc.), and to contain ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) genes located in nucleolar organizer regions (NORs) of short arms of the acrocentric chromosomes using an acro-p-arm probe (Abbott/Vysis, Inc.) (Fig. 1g, insertions 1–2). Telomere FISH did not show telomere repeats in fusion sites of the 1q JTs using telomere-specific (TTAGGG)3 probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (Fig. 1g, insertion 2).

Literature review of 1q JTs in myeloid neoplasms

A literature search revealed 48 cases of myeloid neoplasms with 1q JTs (including our patient, Table 1) [5, 6, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Of 40 patients who did not have AML at the time of diagnosis, 21 (52.5%) transformed to AML and had a poor outcome. In terms of recipient chromosomes, 1q JTs in myeloid malignances have been fused to the telomere regions of recipient chromosomes in 81% of 149 1q JTs, and more than half of these fused to the short arms of the five acrocentric chromosomes in the human genome (Table 1). In terms of recipient chromosomes, among 149 1q JTs in 48 patients with myeloid neoplasms, 43% of the fusions occurred in short arms of acrocentric chromosomes, 38% occurred in telomeric regions of chromosome arms, 11% occurred in the pericentromeric/centromere regions, and 8% occurred in interstitial regions of recipient chromosomes (Fig. 1f). The most frequently seen fusions are in short arms of all five acrocentric chromosomes including 15p (12%), 14p (8.8%), 22p (8.8%), 21p (7.5%), and 13p (6.1%) (Table 1).

Discussion and conclusions

Our patient had MDS with pathogenic mutations of the TET2, RUNX1, SRSF2, and ASXL1 genes and developed 1q JTs at the time of progression from MDS to AML. Our data suggest that the formation of 1q JTs may involve multiple stages, including pathogenic mutations of the TET2 gene and/or other myeloid genes, hypomethylation/decondensation of the donor pericentromeric regions of chromosome 1, shortened/dysfunctional telomeres in recipient chromosomes, as well as unique structure of short arms of acrocentric chromosomes.

TET proteins, such as TET2, play key roles in the regulation of DNA-methylation status [25]. The TET2 gene (OMIM*612839) encodes a methylcytosine dioxygenase that catalyzes the conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine [25]. It can both serve as a stable epigenetic mark and participate in active demethylation [25]. Patients with myeloid malignancies and TET2 mutations have a higher response rate with hypomethylating agents (such as azacitidine or decitabine) than patients who are with wild-type for TET2 [26]. The pericentromeric heterochromatin region of chromosome 1 can become hypomethylated by in vitro modification using 5-Azacitidine [8]. The RUNX1 gene (OMIM*151385) encodes a Runt-related transcription factor and binds to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) via a Runt domain. It has a primary role in the development of all hematopoietic cell types and can produce oncogenic transformation to AML. Recent data also suggested that RUNX1 contributes site specificity of DNA demethylation by recruitment of TET2 and other demethylation-related enzymes to its binding sites in hematopoietic cells [27]. The SRSF2 gene (OMIM*600813) is a splicing factor, which is required for spliceosome assembly. It regulates constitutive and alternative splicing and maintains genome stability through the prevention of R-loop structure formation during transcription [28, 29]. The ASXL1 gene (OMIM*612990) encodes for a chromatin-binding protein and disrupts chromatin in localized areas which leads to enhanced transcription of some genes, while repressing the transcription of others [30]. It facilitates a chromatin polycomb protein to maintain both activation and silencing of homeotic genes [31]. Through interaction with the PRC2 complex, loss of ASXL1 results in a genome-wide reduction in H3K27 trimethylation [31]. Pathogenic mutations of the TET2 gene along with other genes and/or treatment with azacitidine in our patient may have played a role in hypomethylation/de-condensation of pericentromeric heterochromatin of chromosome 1.

Most reported cases with 1q JTs were characterized by banding and FISH methods with fusion breakpoints on chromosome 1 mainly in its long arm (1q10-q12, 1q21), and rarely in its short arm (1p10-p11). Our patient had a pericentromeric 1p11 band in the short arm of chromosome 1 as a breakpoint of the donor chromosome of JTs. In terms of recipient chromosomes, the majority of the fusions occurred in short arms of acrocentric chromosomes (Table 1). The short arms of the five acrocentric chromosomes have a unique structure, with NORs sandwiched between centromeric and telomeric heterochromatin. Proximal (centromeric) side sequences of the NORs are almost entirely segmentally duplicated, like the regions bordering centromeres. As human NORs show enhanced instability in cancers, pericentromeric heterochromatin of chromosome 1 may fuse with similar sequences of the proximal sides of NORs. By FISH analyses, the JTs had a chromosome 1 centromere, NORs at short arms of the recipient acrocentric chromosomes, and no telomere repeats in fusion sites. Therefore, fusion sites of 1q JTs in our case had NORs, but no telomere repeats (Fig. 1g, insertion 2), which may shed light on why 43% reported 1q JTs in myeloid malignances are in the short arms of the five acrocentric chromosomes (Fig. 1f).

Telomere length has been reported to be decreased in AML cells with JTs [7] and telomere shortening, or dysfunctional telomeres may contribute to the formation of 1q JTs, which may explain why 38% of reported 1q JTs occurred in telomeric regions of chromosome arms (Fig. 1f). One cell in our patient had a deleted chromosome 1 with loss of the 1p12 - 1p36.3 segment, but had telomere repeats on both telomere ends (Fig. 1g, insertion 1), suggesting the presence of a chromosome healing event leading to addition of a new telomere onto a chromosome break.

Our data suggest that the formation of 1q JTs involves multiple stages (Fig. 1g). The leukemic process in our patient was likely initiated by pathogenic mutations in MDS/AML disease-related genes, leading to MDS. Then mutations of myeloid genes and treatment with a hypomethylating agent (such as azacitidine in our patient) may lead to hypomethylation/de-condensation of pericentromeric/centromere heterochromatin of chromosome 1, resulting in a broken chromosome 1 with a pericentromeric/centromere break. Additionally, telomere shortening/dysfunction increased susceptibility to genomic/chromosome instability. Subsequently, if the broken chromosome 1 without telomeres was not restored by a chromosome healing event by seeding a new telomere onto a chromosome break, it could be repaired by fusing with either NOR regions of acrocentric chromosomes or shortened telomere ends of recipient chromosomes (possibly through illegitimate recombination) to form 1q JTs in order to achieve their stabilization. The 1q JTs in our patient occurred in the short arms of acrocentric chromosomes 14 and 21, leading to gain of 1q. Finally, 1q JTs cells with extra copies of 1q with or without additional chromosome abnormalities may have a proliferative advantage, leading to disease progression from MDS to AML, clonal evolution and more aggressive disease. Our data may provide a mechanistic model for the generation of JTs in leukemia. Further investigation of sequences around the fusion sites would provide the molecular key to how these events are orchestrated in development and formation of JTs.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article [and its additional files].

Abbreviations

- AML:

-

Acute myeloid leukemia

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- FISH:

-

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

- JTs:

-

Jumping translocations

- MDS:

-

Myelodysplastic syndrome

- NORs:

-

Nucleolar organizer regions

- rRNA:

-

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

References

Berger R, Bernard OA. Jumping translocations. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46(8):717–23.

Gardner RJM, Sutherland GR, Shaffer LG. Chromosome Abnormalities and Genetic Counseling. 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2011.

Sawyer JR, Tricot G, Mattox S, Jagannath S, Barlogie B. Jumping translocations of chromosome 1q in multiple myeloma: evidence for a mechanism involving decondensation of pericentromeric heterochromatin. Blood. 1998;91(5):1732–41.

Jamet D, Marzin Y, Douet-Guilbert N, Morel F, Le Bris MJ, Herry A, et al. Jumping translocations in multiple myeloma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;161(2):159–63.

Najfeld V, Tripodi J, Scalise A, Silverman LR, Silver RT, Fruchtman S, et al. Jumping translocations of the long arms of chromosome 1 in myeloid malignancies is associated with a high risk of transformation to acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2010;151(3):288–91.

Sanford D, DiNardo CD, Tang G, Cortes JE, Verstovsek S, Jabbour E, et al. Jumping translocations in myeloid malignancies associated with treatment resistance and poor survival. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2015;15(9):556–62.

Zou YS, Ouahchi K, Lu Y, Liu W, Christensen T, Schappert J, et al. Jumping translocations of 3q21 in an acute monocytic leukemia (M5) patient reveal mechanisms of multistage telomere shortening in pathogenesis of AML. Leuk Res. 2012;36(1):e31–3.

Sawyer JR, Tian E, Heuck CJ, Johann DJ, Epstein J, Swanson CM, et al. Evidence of an epigenetic origin for high-risk 1q21 copy number aberrations in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2015;125(24):3756–9.

Sawyer JR, Tian E, Walker BA, Wardell C, Lukacs JL, Sammartino G, et al. An acquired high-risk chromosome instability phenotype in multiple myeloma: jumping 1q syndrome. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9(8):62.

Gray BA, Bent-Williams A, Wadsworth J, Maiese RL, Bhatia A, Zori RT. Fluorescence in situ hybridization assessment of the telomeric regions of jumping translocations in a case of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1997;98(1):20–7.

Hatakeyama S, Fujita K, Mori H, Omine M, Ishikawa F. Shortened telomeres involved in a case with a jumping translocation at 1q21. Blood. 1998;91(5):1514–9.

Vermeesch JR, Petit P, Speleman F, Devriendt K, Fryns JP, Marynen P. Interstitial telomeric sequences at the junction site of a jumping translocation. Hum Genet. 1997;99(6):735–7.

Hoffschir F, Ricoul M, Lemieux N, Estrade S, Cassingena R, Dutrillaux B. Jumping translocations originate clonal rearrangements in SV40-transformed human fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 1992;52(1):130–6.

Ben-Neriah S, Abramov A, Lerer I, Polliack A, Leizerowitz R, Rabinowitz R, et al. "jumping translocation" in a 17-month-old child with mixed-lineage leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1991;56(2):223–9.

Busson-Le Coniat M, Salomon-Nguyen F, Dastugue N, Maarek O, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Mozziconacci MJ, et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis of chromosome 1 abnormalities in hematopoietic disorders: rearrangements of DNA satellite II and new recurrent translocations. Leukemia. 1999;13(12):1975–81.

Couture T, Amato K, DiAdamo A, Li P. Jumping translocations of 1q in Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia: report of three cases and review of literature. Case Rep Genet. 2018;2018:8296478.

Lizcova L, Zemanova Z, Malinova E, Michalova K, Smisek P, Stary J. Jumping translocations in bone marrow cells of pediatric patients with hematologic malignancies: a rare cytogenetic phenomenon. Cancer Genet. 2011;204(6):348–9.

Manola KN, Georgakakos VN, Stavropoulou C, Spyridonidis A, Angelopoulou MK, Vlachadami I, et al. Jumping translocations in hematological malignancies: a cytogenetic study of five cases. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;187(2):85–94.

Nagai S, Nannya Y, Takahashi T, Kurokawa M. Jumping translocation involving 1q21 during long-term complete remission of acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2010;89(7):741–2.

Najfeld V, Hauschildt B, Scalise A, Gattani A, Patel R, Ambinder EP, et al. Jumping translocations in leukemia. Leukemia. 1995;9(4):634–9.

Parihar M, Gupta A, Yadav AK, Mishra DK, Bhattacharyya A, Chandy M. Jumping translocation in a case of de novo infant acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(2):387–9.

Reddy KS, Parsons L, Colman L. Jumping translocations involving chromosome 1q in a patient with Crohn disease and acute monocytic leukemia: a review of the literature on jumping translocations in hematological malignancies and Crohn disease. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;109(2):144–9.

Shikano T, Arioka H, Kobayashi R, Naito H, Ishikawa Y. Jumping translocations of 1q in Burkitt lymphoma and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1993;71(1):22–6.

Yeung CCS, Deeg HJ, Pritchard C, Wu D, Fang M. Jumping translocations in myelodysplastic syndromes. Cancer Genet. 2016;209(9):395–402.

Ko M, An J, Pastor WA, Koralov SB, Rajewsky K, Rao A. TET proteins and 5-methylcytosine oxidation in hematological cancers. Immunol Rev. 2015;263(1):6–21.

Bejar R, Lord A, Stevenson K, Bar-Natan M, Perez-Ladaga A, Zaneveld J, et al. TET2 mutations predict response to hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome patients. Blood. 2014;124(17):2705–12.

Suzuki T, Shimizu Y, Furuhata E, Maeda S, Kishima M, Nishimura H, et al. RUNX1 regulates site specificity of DNA demethylation by recruitment of DNA demethylation machineries in hematopoietic cells. Blood Adv. 2017;1(20):1699–711.

Xiao R, Sun Y, Ding JH, Lin S, Rose DW, Rosenfeld MG, et al. Splicing regulator SC35 is essential for genomic stability and cell proliferation during mammalian organogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(15):5393–402.

Lin S, Coutinho-Mansfield G, Wang D, Pandit S, Fu XD. The splicing factor SC35 has an active role in transcriptional elongation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(8):819–26.

Fisher CL, Pineault N, Brookes C, Helgason CD, Ohta H, Bodner C, et al. Loss-of-function additional sex combs like 1 mutations disrupt hematopoiesis but do not cause severe myelodysplasia or leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(1):38–46.

Abdel-Wahab O, Adli M, LaFave LM, Gao J, Hricik T, Shih AH, et al. ASXL1 mutations promote myeloid transformation through loss of PRC2-mediated gene repression. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(2):180–93.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IL analyzed and interpreted the hematopathology and cytogenetic data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MG analyzed and interpreted the cytogenetic data. EW analyzed and interpreted the cytogenetic data. VHD analyzed and interpreted the clinical data. MRB analyzed and interpreted the clinical data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. YZ analyzed and interpreted the cytogenetic data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics committee approval was not required for this single-patient case report.

Consent for publication

The patient is deceased, and requirement for consent for publication was waived.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, I., Gudipati, M.A., Waters, E. et al. Jumping translocations of chromosome 1q occurring by a multi-stage process in an acute myeloid leukemia progressed from myelodysplastic syndrome with a TET2 mutation. Mol Cytogenet 12, 47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-019-0460-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13039-019-0460-2