Abstract

Previous studies have suggested that Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) affect individuals across their lifespan, especially in relation to employment. The purpose of this review was to synthesize the results from studies examining the prospective association of ADHD diagnosis in childhood and later education, earnings and employment, compared to children without an ADHD diagnosis. A review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (ID = CRD42019131634). The findings were reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. The systematic review is based on a structured and preplanned analysis of original prospective longitudinal studies. A total of 2505 potential records were identified, two through backward search. Six papers met the inclusion criteria. One paper was assessed as good, four as fair and one as poor quality. The studies indicated that ADHD diagnosis affected the nature of the individual’s attachment to the labour market across different labour market attachment outcomes. Adults with persisting symptoms, had significantly more problems at work. Even if ADHD symptoms desist in adulthood, the negative impact of earlier ADHD symptoms can still be seen on occupational outcomes. Significantly fewer probands had a Bachelor’s degree compared to controls. Based on one good quality study and four fair quality studies, it is indicated that patients with childhood diagnosed ADHD, generally experience employment of lower quality compared with peers, in relation to income, education and occupational attainment. The overall level of evidence is rated as poor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

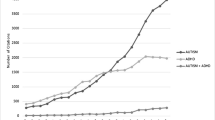

Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) is the most frequently registered psychiatric diagnosis among children and adolescents, and the diagnosis is three times more prevalent among boys than among girls [4]. Girls are more often diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), due to absence of hyperactivity [17]. It is estimated that the worldwide prevalence of ADHD/ADD is 5.3% [14]. Based on a review from 2014 there has been no change in the prevalence across the three last decades [15]. In Denmark, in contrast to the review by Polanczyk et al. [15], the prevalence of ADHD among children and adolescents (0–18 years) has more than tripled from 2006 to 2016, resulting in 25,029 children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD in 2016. The incidence was almost doubled in the same period, with 4128 children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD in 2016 [5]. The reason for the increased prevalence of ADHD, in Denmark, may be due to a greater awareness of ADHD and more children psychiatrist to handle the diagnostics.

ADHD is diagnosed according to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by American Psychiatric Association) [1] and the ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases) of the World Health Organization [19] when inattentiveness, hyperactivity and impulsiveness are present in childhood.

Although most frequently diagnosed during the school years, ADHD is now acknowledged to affect individuals across the lifespan [2]. ADHD is a chronic disorder, that may have important impact on school achievement, education and on the individual’s life course [7, 18]. Around 65% of children with ADHD still have problems in their adult life [18]. Symptoms have been observed to change over time, and the hyperactivity component may decline during adolescence. Inattention symptoms tend to persist into adulthood [6]. Children with ADHD may have concentration- and attention problems, which can result in difficulties in following a normal school program and result in familial problems (e.g., parents, siblings etc.) [7]. Children with ADHD have an increased risk of dropping out of school, and adolescents with ADHD may have difficulties in completing an academic education [18]. Based on this, youths with ADHD seem to achieve a lower level of education and that this may have an impact on the future labour market attachment.

Our hypothesis is that ADHD can affect learning and psychological wellbeing and negatively affect education and later labour market participation. Given the high prevalence of ADHD, this would imply that a large group of youths will not reach the same economic and educational level as peers.

The aim of this study is to describe existing knowledge on prospective associations between ADHD in youth (6–17 years old) and future employment.

Methods

A review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (ID = CRD42019131634). The findings were reported according to the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.

A systematic review was performed of prospective longitudinal studies addressing the impact of childhood ADHD diagnosis on later labour market attainment.

Search strategy

MEDLINE, Web of Science, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews) were used for systematic searching in December 2018 and again in November 2020. A research librarian helped develop the search strategy. The search terms used were “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity”, “attention deficit disorder” or “ADHD”, combined with “adult” and “occupations”, “work”, “employment” or “workplace”.

Study selection

References were imported into Covidence. Title and abstract screening, full-text screening and data extraction were performed independently by two of the authors of this paper. The inclusion criteria were set to include quantitative prospective longitudinal studies, in English, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian. The study population included adults who were diagnosed with ADHD/ADD at age 6–18 years and comparable ADHD/ADD-free controls. No timeframe was set. Studies performed in low- and middle-income countries were excluded in order to increase homogeneity of labour market regimes. If the population included adults not in working age (> 60 years), the study was also excluded. All the included studies needed to have age- and sex-matched comparison participants without ADHD/ADD. Finally, backward searching of reference lists of the located studies were performed. References in systematic reviews on similar topics were also screened to localize further relevant studies.

Quality appraisal

Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [12] was used for assessing the quality of the studies and risk of bias. Quality assessment was independently conducted by all the authors. The first author (MSC) assessed all selected articles and the three other authors assessed a third each. Each article was classified as “good”, “fair” or “poor”. Any disagreements were resolved in collaboration and by discussion with a 3rd person.

Data extraction

The first author (MSC) used a data extraction sheet, to extract data from each of the included studies. Afterwards the second author (ML) checked the data. Disagreements were solved through discussion. The collected information included author name, publication date, objectives, study design, study period, follow-up, population, inclusion/exclusion criteria, variables of interest, measurement, statistical methods, participants, confounders, outcome data, main results and limitations.

Results

A PRISMA flow diagram of the search results and reasons for study exclusion can be found in Additional file 1: Figure S1.

The initial literature search provided 2505 references. After removal of duplicates, 2028 references were left for title and abstract screening. Of these, 30 references were relevant for full text screening, and of these four articles were included. Backward searching of reference lists of the located studies, provided two more relevant articles. Screening of the studies included in previous reviews on similar topics did not provide further relevant articles. The search was repeated in November 2020, yielding an additional 15 studies eligible for screening. No additional studies were included following abstract and full-text screening. The search yielded a new systematic review with relevance for this review, but the studies included did not fulfill the inclusion criteria for the present review.

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the six studies meeting inclusion criteria. All studies used DSM as diagnostic criteria to identify the ADHD study population. All studies included measures related to occupation and education at follow-up [3, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16], five studies included information on financial follow-up outcomes [3, 8, 10, 13, 16]. Two studies included follow-up information of general socioeconomic position [3, 10].

The six studies were published between 1993 and 2017 (median 2015). The combined study populations of the included studies totaled 2268 individuals, of which 1380 were probands and 888 were controls. However, two studies [8, 16] were based on the same study population. Thus, the true size of the total population under study was 904 probands and 647 controls, totaling 1551 individuals. Overall, this indicates generally small to medium sized studies, ranging from 169 individuals [3] to 717 individuals [8, 16]. All the studies were based on identification of probands in clinical or educational settings and age- and gender matched ADHD-free controls [3, 8, 10, 11, 13, 16]. Follow-up periods ranged from 16 [8, 16] to 33 years [10]. None of the included studies addressed ADD directly, but one study included one person with ADD [11].

General description of study participants

Age at inclusion of study participants ranged from six to seventeen years of age. Two studies did not report gender distribution but included both females and males, n = 717 for both studies [8, 16]. Of the remaining four studies, one study exclusively included females (n = 208) [13] and three studies exclusively included males, (Klein et al. n = 271, Biederman et al. n = 169, Mannuzza et al. n = 186) [3, 10, 11].

Assessment of quality of included studies

The quality appraisal of the 6 papers resulted in one paper assessed as good quality [13], four as fair quality [3, 8, 11, 16], and one as poor quality [10] (Table 2). The four authors were in agreement in 50% of the classifications into good, fair and poor quality categories. Based on the quality assessment, only the results from the five studies rated fair or good quality [3, 8, 11, 13, 16] were included in the review results (Table 3).

Due to low quantity of included studies, heterogeneous outcomes and generally low quality of the included studies, meta-analysis and test for heterogeneity was not deemed feasible.

Labour market attachment

Occupational attainment was assessed using different measures; (un)employment, number of jobs, average job length, times fired or quit, employment level/rank, occupation/industry.

Job changes

Two studies used self-reported job changes “total number of times fired or quit” [8, 16]. Roy et al. found that number of times fired or quit was predicted by a high baseline ADHD severity score (OR = 1.20, p < 0.001) [16]. Hechtman and colleagues found no significant differences between number of jobs held among probands (2.2, SD = 1.3) and controls (2.1, SD = 1.3) (p = 0.08). ADHD probands had experienced twice as many job changes due to having quit or being fired (0.61 SD = 1.06 vs. 0.32 SD = 0.64, p < 0.001), and had a significantly shorter average job length (381 SD = 341 vs. 422 SD = 325, p < 0.001). No unit for the measure of job length was provided [8].

Problems at work

Information about problems at work was obtained using a project-derived structured interview. Owens et al. found that girls with persistent ADHD across all study waves showed significantly more problems at work than the other groups (desisters and controls, ds = 0.69–0.94) [13]. According to self-report, employment functioning was essentially equivalent across groups, with the exception that controls reported significantly better functioning at work than girls with persistent ADHD (d = 0.68). Overall, employment outcomes among comparisons were slightly better than desisters [13].

Occupational rankings

Two studies used occupational rankings according to Hollingshead et al. [3, 9, 11]. Mannuzza and colleagues found that about 90% of subjects in each group were employed at follow-up, but probands had significantly lower occupational rankings than those of controls (ranking 3.5 vs. 4.4; P < 0.0001) [11]. Likewise, Biederman and colleagues found occupational level significantly lower within the ADHD group compared to controls (mean 5.2 vs. 6.6 p = 002, scale score range 1–9), also after controlling for total number of psychiatric disorders other than ADHD [3]. In order to study potential differences in the type of work adults with or without ADHD were employed in, Mannuzza and colleagues also investigated differences in job type between probands and controls, and found the largest discrepancy occurred among the higher-ranking positions, e.g., 21% of controls vs. only 4% of probands were employed as professionals (P < 0.001). Conversely, group rates were comparable for lower-ranking positions and among skilled workers. Whether they owned and operated their own business was also reported, and it was found that 18% of the probands and 5% of controls were owners of small businesses [11].

The ADHD diagnosis seems to affect the nature of the individual’s attachment to the labour market [3, 8, 11, 13, 16] across different labour market attachment outcomes.

Earnings

Public assistance and income

Four studies have investigated the economic situation in adulthood of participants with a history of ADHD in childhood [3, 8, 13, 16]. In the study by Hechtman and colleagues it was found that 16% of probands received public assistance, where it was 3.2% of controls [8]. The comparisons of the ADHD subgroups relation to previous year income showed that the subgroup with persistent symptoms showed the worst outcomes, the symptom-desistent subgroup intermediate and controls the best [8].

Roy and colleagues found significantly increased likelihood (OR = 1.50 SE = 0.13 p = 0.02) of receiving public assistance in adulthood, with higher baseline ADHD symptom severity, compared to ADHD free controls [16].

Among 140 girls with ADHD and 88 age- and ethnicity-matched comparison girls, Owens and colleagues used ANOVAs and eight chi-squared tests and found no statistically significant difference between probands and controls in relation to receiving public assistance [probands 14.1% controls 38.0% (p = 0.012)], or in current salary levels [probands 2087 (SD = 1896) controls 1167 (SD = 1420) (p = 0.023)] [13]. Finally, men who had ADHD as boys were significantly more likely to be financially dependent on their parents compared to controls (26.6% vs. 13.3% p = 0.03) [3]

Socio-economic position

Biederman et al. was the only study that reported Socioeconomic Status (SES) at follow-up (16 years follow-up). SES was measured using the 5-point Hollingshead scale, with high score equaling low SES. At follow-up, the mean age was 27.4 years old. Biederman and colleagues followed 79 boys with ADHD and 90 controls and found that participants with ADHD in childhood that were financially independent, had significantly lower personal SES (mean 1.7 SD = 0.8) than controls (mean 1.4 SD = 0.6) (p = 0.02) at follow-up [3].

Educational attainment

All the five included studies comprised measures of educational attainment at follow-up. These can be roughly divided into two main categories: educational achievement [3, 8, 11, 13, 16] and obtained college/university degree [3, 8, 11, 16]. In addition to this, one study addressed educational functioning [13].

Educational achievement

Owens and colleagues found higher educational degrees among controls than among ADHD cases: On a 6-point scale, the group most affected by ADHD had a score of 1.7 (SD 1.1) versus 3.2 (SD 1.4) among the controls (p < 0.001) [13]. This finding was confirmed by the findings by Hechtman and colleagues, who showed that 61.7% of probands had high school or less, where this was the case for 39.2% of controls [8]. Proportions with college or trade education as highest degree was 23.2 percent among probands and 18.8 among controls. Among controls 42.1% had a bachelors or master’s degree—this was the case for 15.1% of the probands. The unadjusted association was found to be statistically significant (p < 0.001) [8]. Biederman and colleagues used the Hollingshead scale to analyze potential differences in educational level. On a scale score range from 1 to 7 where higher values indicated higher educational levels, controls had a mean score of 6.1, probands 5.1 (p < 0.001) [3]. Mannuzza and colleagues showed analyses compatible to the study by Hecthman and colleagues [8, 11]: The proportion with high school or less was 63% among probands and 27% among controls, and probands had finished 2 years less schooling than controls (p < 0.001) [11] (Table 4).

Obtained college/university degree

Three papers addressing associations between ADHD and receiving a university degree were based on two underlying studies: Two papers were based on The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD [8, 16] and one was based on children referred to the same no-cost child psychiatry clinic [11].

According to Roy and colleagues, the chance for probands to obtain a bachelor’s degree decreased with ADHD symptoms severity measured with the SNAP (Swanson, Nolan and Pelham) scale, where a 1-step increase on the 4-category SNAP scale assessed at baseline had an OR of 0.69 (SE = 0.11; P = 0.02) for obtaining a bachelor’s degree in adulthood [16]. Based on the same data material, Hechtman and colleagues confirmed this association: ADHD-free controls had a OR of 1.29 for obtaining a bachelor’s degree during follow-up compared to probands [8]. Biederman and colleagues found a comparable educational gradient, as 84.6% of controls had obtained a bachelor degree at follow-up, where this was the case for 37.9% of probands (p < 0.001) [3].

Mannuzza and colleagues found similar associations among children referred to a child psychiatric clinic and diagnosed with ADHD, compared to a ADHD-free group of matched controls: 12% of probands had complete a bachelor’s degree or higher at follow-up, compared to 49% of controls (p < 0.001) [11].

Educational functioning

Owens and colleagues showed higher educational functioning scores among controls than among probands. The educational functioning was reported by the participants, clinicians and the participants parents. All groups had the highest educational functioning score among controls, and the score was lowest among the “persisters” (participants who met ADHD criteria at all waves) [13].

Conclusions

Of the six studies meeting inclusion criteria, one was rated of good quality, four of fair, and one of poor quality. Based on the five studies rated fair or good, it is indicated that patients with ADHD generally experience employment of lower quality (lower lifetime income, more prone to part time and unskilled work) and are more likely to receive public assistance.

While ADHD is shown to be a significant negative predictor for future occupational outcomes, other factors such as socioeconomic status and test scores can work opposite to this. This suggests that adult outcomes for ADHD patients can be affected. However, it is currently not evident from existing literature, included in this article, which factors positively affect educational and occupational attainment. Given the significant size of the patient population, finding ways to better adult outcomes would have large implications. Overall, the scarcity and quality of the studies meeting inclusion criteria suggest that the level of evidence for the associations targeted in this systematic review is deemed as poor. This should warrant further research addressing which factors and interventions help reduce the long-term vocational effects of childhood ADHD and especially ADD which is not addressed in the present literature.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADHD:

-

Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder

- ADD:

-

Attention Deficit Disorder

- DSM-IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders by American Psychiatric Association

- IDC-10:

-

International classification of diseases

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- SNAP scale:

-

Swanson, Nolan and Pelham scale

References

APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. Young adult follow-up of hyperactive children: antisocial activities and drug use. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):195–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00214.x.

Biederman J, Petty CR, Woodworth KY, Lomedico A, Hyder LL, Faraone SV. Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 16-year follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(7):941–50. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11m07529.

Danish Health Authority. Forløbsprogram for børn og unge med ADHD. 2017. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2017/~/media/930B6F0B2829492A8CB5BC434CA5DE4A.ashx2017 Accessed 1 Feb 2019.

Danish Health Authority. Praevalens, Incidens og Aktivitet i Sundhedsvaesenet for børn og unge med angst eller depression, ADHD og spiseforstyrrelser. 2017. https://www.sst.dk/da/udgivelser/2017/~/media/930B6F0B2829492A8CB5BC434CA5DE4A.ashx2017 Accessed 1 Feb 2019.

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Mick E. The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychol Med. 2006;36(2):159–65. https://doi.org/10.1017/s003329170500471x.

Harpin VA. The effect of ADHD on the life of an individual, their family, and community from preschool to adult life. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(Suppl 1):i2-7. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.059006.

Hechtman L, et al. Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: MTA results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(11):945-52.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774.

Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC. Social class and mental illness: a community study. 1958. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1756–7. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.97.10.1756.

Klein RG, et al. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295–303. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271.

Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(7):565–76.

NHLBI Study Quality Assessment Tools. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools. Accessed 29 Aug 2019.

Owens EB, Zalecki C, Gillette P, Hinshaw SP. Girls with childhood ADHD as adults: cross-domain outcomes by diagnostic persistence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(7):723–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000217.

Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942.

Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):434–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt261.

Roy A, et al. Childhood predictors of adult functional outcomes in the multimodal treatment study of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (MTA). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(8):687-95.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.05.020.

Swanson JM, Sergeant JA, Taylor E, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Jensen PS, Cantwell DP. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and hyperkinetic disorder. Lancet. 1998;351(9100):429–33.

Weiss G, Hechtman L, Milroy T, Perlman T. Psychiatric status of hyperactives as adults: a controlled prospective 15-year follow-up of 63 hyperactive children. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1985;24(2):211–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60450-7.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank librarian Elizabeth Bengtsen from The National Research Center for the Working Environment for her invaluable help in searching for literature.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MSC, ML, LK and TL conceptualized the idea of this review paper. MSC and ML performed the literature search for the review. MSC, ML and TL drafted the review. MSC, ML, LK and TL revised the review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Search results and reason for study exclusion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Christiansen, M.S., Labriola, M., Kirkeskov, L. et al. The impact of childhood diagnosed ADHD versus controls without ADHD diagnoses on later labour market attachment—a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 15, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00386-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-021-00386-2