Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the difference between hepatitis B virus related hepatocellular carcinoma (HBV-HCC) and non-HBV non-HCV hepatocellular carcinoma (NBNC-HCC) patients based on clinical features and prognosis.

Methods

A total of 175 patients with HCC were enrolled. Patients’ characteristics were extracted from medical records. Among them, 107 patients were positive for HBsAg and negative for HCV-Ab while 68 patients were negative for HBsAg and HCV-Ab.

Results

The patients in the NBNC-HCC group were significantly older than those in the HBV-HCC group (P = 0.045). Moreover, vascular invasion was found in 23.4% of HBV-HCC patients, which was significantly higher than that in the NBNC-HCC patients with 10.3% (P = 0.029). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that HBV-HCC patients had significantly worse outcomes in terms of overall survival (P = 0.036). Compared with the NBNC-HCC patients, the HBV-HCC patients had a significantly worse disease-free survival (P = 0.0018). The multivariate analysis results indicated that TNM stage (HR = 1.541, 95%CI 1.072–2.412, P = 0.002) and HBV infection (HR = 1.087, 95%CI 1.012–1.655, P = 0.042) were independent risk variables for overall survival. While vascular invasion (HR = 1.562, 95%CI 1.013–2.815, P = 0.042) and HBV infection (HR = 1.650, 95%CI 1.017–2.676, P = 0.037) were independent risk factors associated with disease-free survival.

Conclusion

Our data revealed that HBV-HCC is more common in young males with vascular invasion, while NBNC-HCC occurs mostly in elderly patients, and overall survival rate is significantly better than that of HBV-HCC. Our study therefore provides evidence that patients with HBV-HCC require closer follow-up due to their poor prognosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies. Approximately 437,000 people are diagnosed with HCC each year, of which approximately 50% belong to East Asia [1,2,3]. Although treatment of HCC has improved over the decades, the 5-year survival rate of HCC patients is still low with about only 26% of HCC patients surviving [1,2,3,4,5]. The most prominent causes associated with HCC include chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) [6,7,8,9]. Although HBV-associated HCC is the largest proportion of patients with HCC in East Asia, the proportion of HCC cases without hepatitis virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis C antibody (HCV-Ab) positive (NBNC-HCC) is growing rapidly [3,4,5, 10]. The background and molecular mechanisms of NBNC-HCC are unclear. However, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and metabolic syndrome are considered important risk factors for these patients [11,12,13,14]. Although the most important risk factors for HCC are HBV and HCV, the alcohol consumption and exposition to aflatoxin B1 are also important risk factors for HCC [15, 16]. Chronic alcohol abuse and aflatoxin B1 exposure have been widely described as two of the leading risk factors of HCC. The annual HCC rate among Child Pugh Class A or B alcoholic cirrhosis is about 2.5% and the urinary excretion of aflatoxin metabolites have been described associated with a 4 fold increase in HCC risk [15, 16].

Previous studies have compared the clinicopathological features and prognosis of HCC patients with HBV and HCV infections [17,18,19]. However, both of them are caused by chronic viral infection. The etiology of NBNC-HCC is mostly a metabolic factor [20, 21]. The tumor physiological characteristics are quite different from HCC caused by HBV and HCV. Several studies have compared NBNC-HCC patients with virus-related HCC patients with inconsistent results, possibly due to differences in demographic and tumor factors, and the number of patients in the cohort may be insufficient [22,23,24].

To further verify the difference between HBV-related HCC (HBV-HCC) and NBNC-HCC patients, we analyzed the clinical features and prognosis to provide potential evidence for different treatment strategies for HCC patients.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

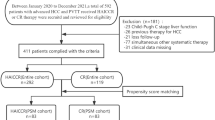

This was a retrospective study. Patients’ characteristics were extracted from medical records. In our study, patients were included if they (1) had pathologically confirmed HCC (2) underwent hepatectomy, and (3) have medical data for hepatitis viral infection status of HBsAg and HCV-Ab. Patients were excluded if (1) they had an additional carcinoma, (2) they were HCV-Ab positive, or (3) their clinical data were not complete. To control the bias, patients were included in the study consecutively. The flow chart is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. A total of 175 patients with HCC, who underwent hepatectomy were enrolled. Among them, 107 patients were positive for HBsAg and negative for HCV-Ab for at least 6 months [23]. A total of 68 cases were negative for HBsAg and negative for HCV-Ab. The study was approved by the medical ethics committee. In our study, HCC was diagnosed with pathological evidences and the stage of HCC was determined according to the TNM classification. TNM staging was defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging for Liver Tumors as follows: (1) Primary tumor (T): (TX) Primary tumor cannot be assessed; (T0) no evidence of primary tumor; (T1) solitary tumor without vascular invasion; (T2) solitary tumor with vascular invasion or multiple tumors less than 5 cm in size; (T3a) multiple tumors more than 5 cm in size; (T3b) single tumor or multiple tumors of any size, involving a major branch of the portal vein or hepatic vein; and (T4) tumor(s) with direct invasion of adjacent organs, other than the gallbladder, or with perforation of visceral peritoneum. (2) Regional lymph nodes (N): (NX) regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed; (N0) no regional lymph node metastasis and (N1) regional lymph node metastasis. (3) Distant metastasis (M): (M0) no distant metastasis and (M1) distant metastasis.

Clinical features

Clinical and pathological data on all patients, including age, gender, preoperative alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), tumor size, tumor number, capsule, and tumor differentiation were collected. Follow-up was conducted using telephonic interview. The postoperative survival of the two groups was observed. The effects of HBV- and NBNC- on the clinicopathological features and prognosis of HCC were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software (version 13; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Student’s t test and Chi square test were used to examine the correlation between different etiologies and clinical and pathological variables. The Kaplan-Meier method (logarithmic rank test) was used to construct the survival curve. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to assess the independence of etiology in prediction results. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Association of etiology with HCC clinical features

To determine the differences between the potential clinical features of NBNC-HCC and HBV-HCC, the relationship between etiology and the clinical features of patients with HCC was evaluated. The results showed that NBNC-HCC patients were significantly older than patients with HBV-HCC (P = 0.045). Moreover, vascular invasion was found in 23.4% of HBV-HCC patients, which was significantly higher than that in NBNC-HCC patients with 10.3% (P = 0.029), as shown in Table 1.

Association of etiology with clinical outcomes in patients with HCC

To determine the differences in etiologies and clinical outcomes among HCC patients, we conducted a Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. For the HBV-HCC patients, the Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that they had significantly worse outcomes in terms of overall survival (P = 0.036). Similarly, compared with the NBNC-HCC patients, HBV-HCC patients had a significantly worse disease-free survival (P = 0.0018), as shown in Fig.1.

Different prognosis among patients with NBNC-HCC and HBV-HCC. a. Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that HBV-HCC significantly worse outcomes in terms of overall survival (P = 0.036). b. Compared with the patients of NBNC-HCC, those with HBV-HCC had a significantly worse disease-free survival (P = 0.0018)

Univariate and multivariate analyses of prognostic variables in HCC

To evaluate whether HBV infection was an independent risk factor for outcomes in HCC, both univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted. The TNM stage (P = 0.003), vascular invasion (P = 0.002), and HBV infection (P = 0.013) were all shown to be prognostic variables for overall survival in patients with HCC. In the multivariate analysis, only TNM stage (HR = 1.541, 95%CI 1.072–2.412, P = 0.002) and HBV infection (HR = 1.087, 95%CI 1.012–1.655, P = 0.042) were found to be independent prognostic variables for overall survival (Table 2).

We further explored the risk factors associated with disease-free survival (Table 3). Univariate analysis showed that vascular invasion (P = 0.024) and HBV infection (P = 0.026) were risk factors associated with disease-free survival. In the multivariate analysis, vascular invasion (HR = 1.562, 95%CI 1.013–2.815, P = 0.042) and HBV infection (HR = 1.650, 95%CI 1.017–2.676, P = 0.037) were independent risk factors associated with disease-free survival.

Discussion

HBV infection is the main cause of HCC [1, 2]. But the mechanisms of carcinogenesis are different compared with NBNC-HCC [20, 22]. HBV is a DNA virus that causes malignant transformation of hepatocytes mainly through gene integration into chromosomes and activation of oncogenes [25,26,27,28]. The mechanism of NBNC-HCC is still unclear, and metabolic factors may be an important factor [21, 22]. For example, persistent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis can also cause sustained proliferation and repair of hepatocytes [29, 30]. During this process, hepatocytes undergo malignant transformation and eventually lead to the occurrence of HCC. Different carcinogenic pathways may lead to differences in the clinicopathological features and prognosis of HCC. Our study concluded that NBNC-HCC are significantly different from HBV-HCC in clinical features. In our study, we found that patients with HBV-HCC were younger, while patients with NBNC-HCC were older. The study also found that HBV-HCC has a higher proportion of vascular invasion, which may involve certain carcinogenic factors of HBV, such as increased cell motility caused by HBxAg [31,32,33,34]. However, there are still many gaps to be filled.

Massimo found that patients with HBV-HCC are younger than HCV-HCC patients [35]. The data from our study confirmed that patients with HBV-HCC were significantly younger than NBNC-HCC. Moreover, our study found that patients with HBV-HCC were more prone to vascular invasion. The prognosis of HBV-HCC was also worse than that of NBNC-HCC. TNM staging and vascular invasion are also factors influencing the long-term survival of patients with HCC.

There have been some studies comparing the prognostic differences between virus-associated HCC and NBNC-HCC [22,23,24]. Cescon et al. [36] reported that patients with NBNC-HCC have a significantly better relapse free survival rate than patients with HBV-HCC. Other studies have indicated that the survival rate of patients with NBNC-HCC was significantly higher than that of patients with HCV-HCC [37, 38]. Another study has shown that relapse free survival in patients with NBNC-HCC is significantly better than that in patients with HBV-HCC [23]. Our study confirmed that the prognosis of NBNC-HCC patients was superior to that of HBV-HCC patients, in terms of overall survival and disease free survival.

The relationship between prognosis and viral status in HCC patients is controversial. Kondo et al. [37] reported that the prognosis of NBNC-HCC patients is significantly better than that of HBC-HCC and HCV-HCC patients. Another study [39] suggested that the prognosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease related HCC was significantly better than that of HCV-HCC patients. However, Akahoshi et al. [40] suggested that there is no difference in prognosis between NBNC-HCC and other type of HCCs. This may be because the etiology of NBNC-HCC is not clear, and includes metabolic reasons, or alcohol abuse. In our study, we showed that NBNC-HCC patients have a better prognosis than HBV-HCC patients. These results provide further evidence for the prognosis of NBNC-HCC.

Some studies have evaluated prognosis after hepatic resection for HCC patients with different etiologies [41, 42]. Cescon et al. [36] reported that NBNC-HCC patients had significantly better outcomes than HBV-HCC patients did. In our study, we confirmed that the prognosis of NBNC-HCC patients was significantly better than that of HBV-HCC patients. We further found that in patients with HCC, TNM stage and HBV infection were independent prognostic variables for overall survival, while vascular invasion and HBV infection were independent risk factors associated with disease-free survival.

Although serum viral markers are important for HCC screening, ethnicity is another important factor [43]. A study has suggested that ethnicity plays an important role in the diagnosis and treatment of HCC [44]. In addition, the onset of HCC occurs at a median age of 45 in sub-Saharan African people, whereas a mean age of 52 to 65 has been observed in the rest of the world [45, 46]. In our study, the patients enrolled were all Asians and therefore ethnicity cannot be used as a variable. Further studies are needed to evaluate the differences in prognosis between different ethnic groups of HBV-HCC and NBNC-HCC patients.

There were some limitations in this study. First, the sample size was relatively small, so the results may be biased. The data collected in this study came from a single center and may lead to some enrollment bias; therefore, a multicenter prospective study is needed to further validate the results. Thirdly, since HCV-infected patients are relatively fewer in China, HCV-HCC patients were not enrolled in this study.

In summary, the clinicopathological features and prognosis of HBV-HCC and NBNC-HCC are significantly different. HBC-HCC is more common in young males with vascular invasion, while NBNC-HCC occurs mostly in elderly patients, and overall survival rate is significantly higher than that of HBV-HCC patients.

Availability of data and materials

Authors can confirm all relevant data are included in the article and materials are available on request from the authors.

References

Clinical Practice Guidelines EASL. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236.

Bertuccio P, Turati F, Carioli G, Rodriguez T, La Vecchia C, Malvezzi M, Negri E. Global trends and predictions in hepatocellular carcinoma mortality. J Hepatol. 2017;67(2):302–9.

El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118–27.

Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. LANCET. 2012;379(9822):1245–55.

Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. LANCET. 2018;391(10127):1301r1314.

Chan AW, Wong GL, Chan HY, Tong JH, Yu YH, Choi PC, Chan HL, To KF, Wong VW. Concurrent fatty liver increases risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(3):667–76.

Cai SH, Lu SX, Liu LL, Zhang CZ, Yun JP. Increased expression of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha transcribed by promoter 2 indicates a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10(10):761–71.

Cai SH, Lv FF, Zhang YH, Jiang YG, Peng J. Dynamic comparison between Daan real-time PCR and Cobas TaqMan for quantification of HBV DNA levels in patients with CHB. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:85.

Zheng C, Yan H, Zeng J, Cai S, Wu X. Comparison of pegylated interferon monotherapy and de novo pegylated interferon plus tenofovir combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:845–54.

Cai S, Ou Z, Liu D, Liu L, Liu Y, Wu X, Yu T, Peng J. Risk factors associated with liver steatosis and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B patient with component of metabolic syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6(4):558–66.

Jeng KS, Chang CF, Jeng WJ, Sheen IS, Jeng CJ. Heterogeneity of hepatocellular carcinoma contributes to cancer progression. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;94(3):337–47.

Kulik L, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(2):477–91.

Ozakyol A. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC epidemiology)[J]. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2017;48(3):238–40.

Cai S, Cao J, Yu T, Xia M, Peng J. Effectiveness of entecavir or telbivudine therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection pre-treated with interferon compared with de novo therapy with entecavir and telbivudine. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(22):e7021.

Petruzziello A. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) related hepatocellular carcinoma. Open Virol J. 2018;12:26–32.

Romeo R, Petruzziello A, Pecheur EI, Facchetti F, Perbellini R, Galmozzi E, Khan NU, Di Capua L, Sabatino R, Botti G, et al. Hepatitis delta virus and hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Epidemiol Infect. 2018;146(13):1612–8.

El-Maksoud MA, Habeeb MR, Ghazy HF, Nomir MM, Elalfy H, Abed S, Zaki M. Clinicopathological study of occult hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis C virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31(6):716–22.

Hassan I, Gane E. Improving survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma related to chronic hepatitis C and B but not in those related to non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis or alcoholic liver disease: a 20‐year experience from a national programme[J]. Intern Med J. 2019;49(11):1405–11.

Hester CA, Rich NE, Singal AG, Yopp AC. Comparative analysis of nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis- versus viral hepatitis- and alcohol-related liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2019;17(4):322–9.

Kim J, Kang W, Sinn D H, et al. Potential etiology, prevalence of cirrhosis, and mode of detection among patients with non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea[J]. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35(1):65.

Tateishi R, Uchino K, Fujiwara N, Takehara T, Okanoue T, Seike M, Yoshiji H, Yatsuhashi H, Shimizu M, Torimura T, et al. A nationwide survey on non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan: 2011-2015 update. J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(4):367–76.

Okuda Y, Mizuno S, Shiraishi T, Murata Y, Tanemura A, Azumi Y, Kuriyama N, Kishiwada M, Usui M, Sakurai H, et al. Clinicopathological factors affecting survival and recurrence after initial hepatectomy in non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma patients with comparison to hepatitis B or C virus. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:975380.

Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, Ichida T, Matsui O, Izumi N, Matsuyama Y, Sakamoto M, Nakashima O, Ku Y, et al. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11,950 patients. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):513–20.

Zhang R, Zhou S, Xiao L, Zhang H, Tulahong A, Zhang Y, Wen H, Bao Y. Comparison of clinical characteristics of non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma and prognosis in Uighur patients. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2015;37(7):540–4.

Cai S, Li Z, Yu T, Xia M, Peng J. Serum hepatitis B core antibody levels predict HBeAg seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients with high viral load treated with nucleos(t) ide analogs. Infect Drug Resist. 2018;11:469–77.

Maini MK, Gehring AJ. The role of innate immunity in the immunopathology and treatment of HBV infection. J Hepatol. 2016;64(1 Suppl):S60–70.

Cai S, Yu T, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, Lv F, Peng J. Comparison of entecavir monotherapy and de novo lamivudine and adefovir combination therapy in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B with high viral load: 48-week result. Clin Exp Med. 2016;16(3):429–36.

Xue X, Cai S, Ou H, Zheng C, Wu X. Health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis B during antiviral treatment and off-treatment. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:85–93.

the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J HEPATOL. 2016;64(6):1388–402.

Oh HJ, Kim TH, Sohn YW, Kim YS, Oh YR, Cho EY, Shim SY, Shin SR, Han AL, Yoon SJ, et al. Association of serum alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase levels within the reference range with metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17(1):27–36.

Chen SL, Liu LL, Lu SX, et al. HB x‐mediated decrease of AIM 2 contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis[J]. Mol Oncol. 2017;11(9):1225–40.

Huang JY, Bi Y, Zuo GW, et al. Effects of HBx on localization of PPARγ in HepG2 cell line[J]. Acta Acad Med Militaris Tertiae. 2008;18:1693–96.

Kim WH, Hong F, Jaruga B, Hu Z, Fan S, Liang TJ, Gao B. Additive activation of hepatic NF-kappaB by ethanol and hepatitis B protein X (HBX) or HCV core protein: involvement of TNF-alpha receptor 1-independent and -dependent mechanisms. FASEB J. 2001;15(13):2551–3.

Ringelhan M, O'Connor T, Protzer U, Heikenwalder M. The direct and indirect roles of HBV in liver cancer: prospective markers for HCC screening and potential therapeutic targets. J Pathol. 2015;235(2):355–67.

Colombo M. Natural history and pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 1999;31(Suppl 1):25–30.

Cescon M, Cucchetti A, Grazi GL, Ferrero A, Vigano L, Ercolani G, Ravaioli M, Zanello M, Andreone P, Capussotti L, et al. Role of hepatitis B virus infection in the prognosis after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: a Western dual-center experience. Arch Surg. 2009;144(10):906–13.

Kondo K, Chijiiwa K, Funagayama M, Kai M, Otani K, Ohuchida J. Differences in long-term outcome and prognostic factors according to viral status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(3):468–76.

Kaneda K, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Takemura S, Ohba K, Uenishi T, Kodai S, Shinkawa H, Urata Y, Sakae M, et al. Features and outcome after liver resection for non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(118):1889–92.

Reddy SK, Steel JL, Chen HW, DeMateo DJ, Cardinal J, Behari J, Humar A, Marsh JW, Geller DA, Tsung A. Outcomes of curative treatment for hepatocellular cancer in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. HEPATOLOGY. 2012;55(6):1809–19.

Akahoshi H, Taura N, Ichikawa T, Miyaaki H, Akiyama M, Miuma S, Ozawa E, Takeshita S, Muraoka T, Matsuzaki T, et al. Differences in prognostic factors according to viral status in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(5):1317–23.

Li Q, Li H, Qin Y, Wang PP, Hao X. Comparison of surgical outcomes for small hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a Chinese experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(11):1936–41.

Tanaka K, Shimada H, Matsuo K, Nagano Y, Endo I, Togo S. Clinical characteristics and surgical outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma without hepatitis B virus surface antigen or hepatitis C virus antibody. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(3):1170–81.

Van Hees S, Michielsen P, Vanwolleghem T. Circulating predictive and diagnostic biomarkers for hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(37):8271–82.

Da CA, Plymoth A, Santos-Silva D, Ortiz-Cuaran S, Camey S, Guilloreau P, Sangrajrang S, Khuhaprema T, Mendy M, Lesi OA, et al. Osteopontin and latent-TGF beta binding-protein 2 as potential diagnostic markers for HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(1):172–81.

Yang JD, Gyedu A, Afihene MY, Duduyemi BM, Micah E, Kingham TP, Nyirenda M, Nkansah AA, Bandoh S, Duguru MJ, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma occurs at an earlier age in Africans, particularly in association with chronic hepatitis B. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1629–31.

Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, Roberts LR, Schwartz M, Chen PJ, Kudo M, Johnson P, Wagner S, Orsini LS, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE study. Liver Int. 2015;35(9):2155–66.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Hongjie Ou for his helpful assistance in the study.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY and WL designed and guided this study, XX and XY wrote the main manuscript text, prepared all figures and data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board of First affiliated hospital of Xiamen university had approved this study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial interests with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

The flow chart of the study is shown.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xue, X., Liao, W. & Xing, Y. Comparison of clinical features and outcomes between HBV-related and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma. Infect Agents Cancer 15, 11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-020-0273-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13027-020-0273-2