Abstract

Background

Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is treated with a series of methods. High-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) is an option with promising mid-term outcomes. The objective of this study was to determine the long-term outcomes of ESWT for ONFH.

Methods

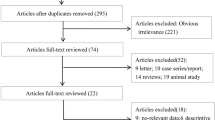

Fifty-three hips in 39 consecutive patients were treated with ESWT in our hospital between January 2005 and July 2006. Forty-four hips in 31 patients with stage I–III nontraumatic ONFH, according to the Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) system, were reviewed in the current retrospective study. The visual analog pain scale (VAS), Harris hip score, radiography, and magnetic resonance imaging were used to estimate treatment results. The progression of ONFH was evaluated by imaging examination and clinical outcomes. The results were classified as clinical success (no progression of hip symptoms) and imaging success (no progression of stage or substage on radiography and MRI).

Results

The mean follow-up duration was 130.6 months (range, 121 to 138 months). The mean VAS decreased from 3.8 before ESWT to 2.2 points at the 10-year follow-up (p < 0.001). The mean Harris hip score improved from 77.4 before ESWT to 86.9 points at the 10-year follow-up. The clinical success rates were 87.5% in ARCO stage I patients, 71.4% in ARCO stage II patients, and 75.0% in ARCO stage III patients. Imaging success was observed in all stage I hips, 64.3% of stage II hips, and 12.5% of stage III hips. Seventeen hips showed progression of the ARCO stage/substage on imaging examination. Eight hips showed femoral head collapse at the 10-year follow-up. Four hips in ARCO stage III and one hip in ARCO stage II were treated with total hip arthroplasty during the follow-up. Three were performed 1 year after ESWT, one at 2 years, and one at 5 years.

Conclusions

The results of the current study indicated that ESWT is an effective treatment method for nontraumatic ONFH, resulting in pain relief and function restoration, especially for patients with ARCO stage I–II ONFH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head (ONFH) is mainly associated with significant hip pain and dysfunction in young adults. ONFH was reported to affect 20,000 patients each year in America [1]. The estimated yearly incidence of ONFH in Korea is 37.96/100000 [2]. Most patients without an effective treatment in the early stage require hip joint replacement. About 49% of untreated asymptomatic ONFH hips progressed to collapse at 49 months following diagnosis [3]. Postcollapse ONFH is one of the most common reasons for primary total hip arthroplasty in many countries [2, 4]. Given the relatively young age at the time of presentation, it is reasonable to preserve the native hip in patients with early-stage ONFH. Several different joint-preserving operative interventions have been reported with promising outcomes in the past decades, including core decompression, osteotomy, and vascularized/nonvascularized bone grafting.

Unlike those operative interventions, biophysical therapy is considered as a noninvasive method for ONFH treatment [5]. Biophysical techniques such as extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) have also been reported to enhance bone formation and preserve the femoral head in osteonecrosis [6, 7]. The use of ESWT in the field of orthopedics started in the 1990s, and the main indications were calcified tendonitis, heel pain, and fracture nonunion [8]. In 2001, the first report on ESWT for ONFH showing promising short-term results was published [6]. Subsequently, a randomized controlled trial showed that ESWT was more effective than core decompression and nonvascularized bone grafting for early-stage ONFH treatment [7]. Some good-to-excellent outcomes in pain relief, functional improvement, and hip survival have been reported in the past decade [9,10,11,12,13]. However, the long-term outcomes of ESWT for ONFH remain unknown. Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the long-term outcomes of ESWT for ONFH.

Methods

The current retrospective study was approved by our institutional review board. Fifty-three hips in 39 consecutive patients underwent ESWT in our hospital between January 2005 and July 2006. Written informed consent was obtained for each patient who participated in the current study according to our institutional policy. The diagnosis of nontraumatic ONFH was based on history, clinical examination, and imaging assessment. The inclusion criteria were patients with symptomatic early-stage ONFH, which was defined as Association Research Circulation Osseous (ARCO) stages I–III ONFH with hip pain and/or dysfunction (Table 1), [14, 15]. The exclusion criteria were ONFH patients with the following: (1) former surgical treatment, (2) history of hip trauma, and (3) ARCO stage IV.

The mean follow-up duration was 130.6 months (range, 121 to 138 months). Five hips in five patients with traumatic ONFH and two hips in one patient with ARCO stage IV ONFH were excluded. Two patients (two hips) were unable to participate in the current study due to personal reasons. Forty-four symptomatic nontraumatic ONFH hips in 31 patients (32 hips in 23 male patients and 12 hips in 8 female patients) with a mean age of 41.2 years (range, 22 to 60 years) were included in the current study (Table 2). Sixteen patients with 24 hips were on a high-dose of corticosteroids. Seven patients with nine hips had a history of alcohol abuse. Eleven hips in eight patients with no established risk factor were considered as having idiopathic ONFH. According to the ARCO classification, eight hips were stage I, 28 hips were stage II, and the remaining were stage III.

ESWT was performed by two senior doctors, under spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia. The patients were placed in the supine position on the radioparent operation table with the limbs secured to the table. The femoral artery was identified and marked on the skin to avoid direct shock during the procession of treatment. The lesion on the femoral head was identified using a C-arm (Siemens, Germany) in ARCO stage II and III patients before treatment. In stage I patients, the lesion was identified according to MRI. Four focal points were selected around the lesion under the C-arm to receive extracorporeal shock wave therapy with an OssaTron (HMT, Switzerland). Each point was treated with 1000 impulses of shock waves at 26 kV and 4 Hz. Treatment was performed bilaterally in 13 patients, and all hips received a single treatment. After treatment, the patient was asked to ensure strict no weight-bearing to limited weight-bearing in the first 3 months; full weight-bearing was allowed at 3 months postoperatively.

The visual analog pain scale (VAS), Harris hip score, and the radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were collected before treatment and during the follow-up. Hip function was evaluated using the Harris hip score. The VAS was used to evaluate pain relief after treatment. Imaging examinations including standardized radiography and MRI were performed to evaluate the ARCO stage of the disease and the bone marrow edema (BME) of the femoral head. According to the range of edema, BME is divided into five grades: grade 0 for no BME, grade 1 for peri-necrotic BME, grade 2 for BME extending into the femoral head, grade 3 for BME extending into the neck of the femur, and grade 4 for BME extending into the intertrochanteric region [10]. The results were classified as a clinical success (no progression of hip symptoms), an imaging success (no progression of stage or substage on the radiography and MRI), or failure (progression of hip symptoms or ARCO stage).

SAS version 8.0 (SAS Institute Inc., USA) was used to perform all statistical calculations. The outcomes at the final follow-up were compared with data before ESWT using the t test. A two-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The mean Harris hip score improved significantly from 77.4 before ESWT to 86.9 points at the 10-year follow-up (p < 0.001). The mean VAS score decreased significantly from 3.8 preoperatively to 2.2 points at the final follow-up (p < 0.001). The outcomes of ESWT were different in patients with different ARCO stages and pathogeny at the final follow-up (Table 3). The clinical success was defined as no progression of hip symptoms, which was observed in 87.5% of ARCO stage I patients, 71.4% of ARCO stage II patients, and 75.0% of ARCO stage III patients. ESWT was most effective in patients with idiopathic ONFH. Four hips in ARCO stage III and one hip in ARCO stage II underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA) during the follow-up, because of aggravated disease with unacceptable pain and hip dysfunction. Three (two hips in ARCO stage IV and one hip in ARCO stage IIIc) underwent THA 1 year after ESWT, one (ARCO stage IV) at 2 years, and one (ARCO stage IV) at 5 years.

All patients received imaging examinations before treatment and at the follow-up. Imaging success was observed in all stage I hips, 64.3% of stage II hips, and 12.5% of stage III hips. At the last follow-up, lesions in three stage I hips and one stage II hip could not be detected on MRI (Fig. 1). A total of 17 hips showed progression of the ARCO stage/substage on radiography or MRI. At the last follow-up, eight hips showed femoral head collapse on standardized radiographs (Table 4). Five of them received THA during the follow-up; the three remaining patients used non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to reduce hip pain. BME around the focal osteonecrosis was observed on MRI before ESWT in all hips included in the current study. Ten hips had grade 1 BME, 6 hips had grade 2 BME, 13 hips had grade 3 BME, and 15 hips had grade 4 BME before ESWT. A reduction in BME was also noted in 30 hips at the final follow-up. Thirteen hips showed no significant change in BME at the final follow-up (Fig. 2). Only one ARCO stage II hip with grade 2 BME progressed to grade 3. In patients with improved BME, the mean VAS score was 1.6 points at the 10-year follow-up, and the mean Harris hip score was 89.7 points at the 10-year follow-up. In patients with unchanged BME, the mean VAS score was 3.5 points and the mean Harris hip score was 79.8 points at the last follow-up. Clinical outcomes were better in the BME improved group than in the BME unchanged group (Table 5).

MRI of a mid-age man with long-term alcohol abuse: a MRI indicated ARCO stage II ONFH with grade 4 BME in the left hip before ESWT; b BME reduction was observed in 3 months after ESWT; c MRI in 5 years after ESWT; d MRI indicated grade 2 BME at the final follow-up. The patient has restored hip function without pain since 5 months after ESWT

Discussion

The current study showed that significant improvements in pain relief and function restoration were maintained for more than 10 years after ESWT. The mean Harris hip score improved from 77.4 before ESWT to 86.9 points at the final follow-up. The mean VAS score decreased from 3.8 preoperatively to 2.2 points at the 10-year follow-up. Four ARCO stage III hips and one ARCO stage II hip underwent THA during the follow-up due to unacceptable pain and hip dysfunction. The improvement of clinical assessments in our study was comparable with those in former short and mid-term reports [6, 7, 9,10,11,12]. In patients with clinical success, pain relief and functional restoration often occurred between 3 months and 1 year after ESWT and were maintained for more than 10 years. The exacerbation of symptoms would appear at 5 months to 10 years after treatment. We consider it necessary to evaluate the affected hip once every year after ESWT.

According to imaging assessments, 14 hips (31.8%) showed improved images with decreased lesion size, and 13 hips (29.5%) showed no significant change in ARCO stage/substage. Seventeen hips (38.6%) showed progression of the ARCO stage, and eight hips (18.1%) showed femoral head collapse on standardized radiographs at the last follow-up. According to imaging assessments, ESWT could prevent progression of the disease in ARCO stage I and II hips. For ARCO stage III hips, a significant progression of the disease was observed during the follow-up. A significant reduction in BME was also noted in most hips at the 10-year follow-up. BME of the proximal femur could be commonly detected by MRI in patients with symptomatic ONFH. BME could increase the bone marrow pressure, which may reduce the blood supply and promote avascular necrosis of the femoral head [16]. A former study by Koo et al. showed that BME of the proximal femur was strongly related to joint pain in patients with early-stage ONFH [17]. Huang et al. analyzed radiograph and MRI scans of 71 ONFH patients and found that 98% of osteonecrotic hips with BME were painful [18]. ESWT has been reported to be effective for the treatment of BME in ONFH patients [9, 10]. In our study, the clinical outcomes in patients with BME reduction are superior to those in other patients, which indicated that physical decompression caused by BME reduction is beneficial to ONFH patients.

The aim of early-stage ONFH treatment is to prevent collapse by delaying the natural progression of the disease. Several joint-preserving operative interventions have been used in the past decade. Given their unpredictable long-term clinical outcomes, none of these methods is generally optimal. Core decompression is the most common joint-preserving operation for early-stage ONFH treatment worldwide. However, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicated that core decompression did not provide a significant difference in the collapse rate when compared with other joint-preserving treatments [19,20,21]. Wang et al. compared the outcome between ESWT and core decompression with bone grafting. ESWT had better clinical outcomes in terms of pain relief, function restoration, and THA rate when compared with core decompression [9]. The present study findings suggest promising long-term results of ESWT for early-stage ONFH.

Several studies also reported that ESWT was more effective in early-stage ONFH (ARCO stage I and II) [7, 10, 11]. Our study confirmed that ARCO stage III patients benefit less from ESWT than ARCO stage I and II patients. The 10-year survival of ARCO stage III hips was 50%, which was also inferior to that of other groups. Based on the information now available, we suggest that further randomized controlled trial studies should be performed to confirm the effectiveness of ESWT for patients with ARCO stage I and II ONFH.

A former study analyzed the outcome of ESWT for ONFH in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients with corticosteroid use [22]. Both SLE and non-SLE patients showed a significant improvement in the clinical outcome and imaging studies, and no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups. Because of the limited number of patients, we are still unable to determine whether different pathogenies could affect the treatment outcome of ESWT. The mean Harris hip score (78.4) and mean VAS score (3.4) in patients with alcohol abuse were inferior to those in patients with corticosteroid-related and idiopathic ONFH at the final follow-up. However, more than half (five of nine hips) of the alcoholic patients had ARCO stage III hips. As we mentioned above, ARCO stage III ONFH is often associated with a poor outcome after ESWT.

As a non-invasive treatment method, ESWT has been reported as an effective treatment method for musculoskeletal diseases since the 1990s. However, the true treatment mechanism of ESWT for pain relief and tissue remolding has not been fully understood. Wang et al. reported that ESWT promoted bone healing by increasing neovessels and upregulated growth factors at the tendon-bone junction [23]. Immunohistochemical examination indicated that ESWT upregulates the expression of vWF, VEGF, and CD31 in the human femoral head [24]. Localized hematoma and cell death caused by direct shock could also promote new bone formation [25]. Several animal studies indicated that the pain relief with ESWT could be owing to diminished pain transmission to the central nervous system. The stimulation of the extracorporeal shock wave to the distal femur could decrease the release of substance P after 6 weeks in rabbits [26]. Moreover, in the dorsal root ganglion of rabbits, neurons immunoreactive for substance P were depressed after extracorporeal shock wave treatment to the distal femur [27]. Based on our results, we hypothesize that the significant pain relief in ONFH patients after ESWT is based on BME reduction. The physical decompression caused by BME reduction would increase the blood supply in focal lesions.

The current study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the current study is limited by its retrospective design. Second, the limited number of participants may have caused bias in the assessment of the outcomes. Third, there was no control group. A comparison between ESWT and other treatments would be useful to determine the superiority of ESWT in the treatment of ONFH in well-selected patients.

Conclusions

In summary, ESWT is an effective treatment method for early-stage nontraumatic ONFH. Significant improvements including pain relief and functional restoration were maintained for more than 10 years after treatment. More large-scale randomized controlled trial studies should be performed to confirm the effectiveness of ESWT for early-stage nontraumatic ONFH.

Abbreviations

- ARCO:

-

Association Research Circulation Osseous

- BME:

-

Bone marrow edema

- ESWT:

-

High-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- ONFH:

-

Osteonecrosis of the femoral head

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- VAS:

-

Visual analog pain scale

References

Hong YC, Luo RB, Lin T, Zhong HM, Shi JB. Efficacy of alendronate for preventing collapse of femoral head in adult patients with nontraumatic osteonecrosis. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:716538.

Kang JS, Park S, Song JH, Jung YY, Cho MR, Rhyu KH. Prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a nationwide epidemiologic analysis in Korea. J Arthroplast. 2009;24:1178–83.

Mont MA, Zywiel MG, Marker DR, McGrath MS, Delanois RE. The natural history of untreated asymptomatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2165–70.

Mankin HJ. Nontraumatic necrosis of bone (osteonecrosis). N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1473–9.

Mont MA, Cherian JJ, Sierra RJ, Jones LC, Lieberman JR. Nontraumatic Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: where do we stand today? A ten-year update. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1604–27.

Ludwig J, Lauber S, Lauber HJ, Dreisilker U, Raedel R, Hotzinger H. High-energy shock wave treatment of femoral head necrosis in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;387:119–26.

Wang CJ, Wang FS, Huang CC, Yang KD, Weng LH, Huang HY. Treatment for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: comparison of extracorporeal shock waves with core decompression and bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2380–7.

Chung B, Wiley JP. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy: a review. Sports Med. 2002;32:851–65.

Wang CJ, Huang CC, Wang JW, Wong T, Yang YJ. Long-term results of extracorporeal shockwave therapy and core decompression in osteonecrosis of the femoral head with eight- to nine-year follow-up. Biom J. 2012;35:481–5.

Wang CJ, Wang FS, Yang KD, Huang CC, Lee MS, Chan YS, et al. Treatment of osteonecrosis of the hip: comparison of extracorporeal shockwave with shockwave and alendronate. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:901–8.

Vulpiani MC, Vetrano M, Trischitta D, Scarcello L, Chizzi F, Argento G, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in early osteonecrosis of the femoral head: prospective clinical study with long-term follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2012;132:499–508.

Chen JM, Hsu SL, Wong T, Chou WY, Wang CJ, Wang FS. Functional outcomes of bilateral hip necrosis: total hip arthroplasty versus extracorporeal shockwave. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:837–41.

Hsu SL, Wang CJ, Lee MS, Chan YS, Huang CC, Yang KD. Cocktail therapy for femoral head necrosis of the hip. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2010;130:23–9.

Gardeniers JWM. Report of the committee of staging and nomenclature. ARCO News Letter. 1993;5:79–82.

Mont MA, Marulanda GA, Jones LC, Saleh KJ, Gordon N, Hungerford DS, et al. Systematic analysis of classification systems for osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 3):16–26.

Meier R, Kraus TM, Schaeffeler C, Torka S, Schlitter AM, Specht K, et al. Bone marrow oedema on MR imaging indicates ARCO stage 3 disease in patients with AVN of the femoral head. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:2271–8.

Koo KH, Ahn IO, Kim R, Song HR, Jeong ST, Na JB, et al. Bone marrow edema and associated pain in early stage osteonecrosis of the femoral head: prospective study with serial MR images. Radiology. 1999;213:715–22.

Huang GS, Chan WP, Chang YC, Chang CY, Chen CY, Yu JS. MR imaging of bone marrow edema and joint effusion in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head: relationship to pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:545–9.

Villa JC, Husain S, van der List JP, Gianakos A, Lane JM. Treatment of pre-collapse stages of osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a systematic review of randomized control trials. HSS J. 2016;12:261–71.

Sadile F, Bernasconi A, Russo S, Maffulli N. Core decompression versus other joint preserving treatments for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a meta-analysis. Br Med Bull. 2016;118:33–49.

Papakostidis C, Tosounidis TH, Jones E, Giannoudis PV. The role of “cell therapy” in osteonecrosis of the femoral head. A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis of 7 studies. Acta Orthop. 2016;87:72–8.

Wang CJ, Ko JY, Chan YS, Lee MS, Chen JM, Wang FS, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave for hip necrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2009;18:1082–6.

Wang CJ, Wang FS, Yang KD. Biological effects of extracorporeal shockwave in bone healing: a study in rabbits. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2008;128:879–84.

Wang CJ, Wang FS, Ko JY, Huang HY, Chen CJ, Sun YC, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy shows regeneration in hip necrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:542–6.

Ogden JA, Toth-Kischkat A, Schultheiss R. Principles of shock wave therapy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;387:8–17.

Maier M, Averbeck B, Milz S, Refior HJ, Schmitz C. Substance P and prostaglandin E2 release after shock wave application to the rabbit femur. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406:237–45.

Hausdorf J, Lemmens MA, Kaplan S, Marangoz C, Milz S, Odaci E, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave application to the distal femur of rabbits diminishes the number of neurons immunoreactive for substance P in dorsal root ganglia L5. Brain Res. 2008;1207:96–101.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KX participated in the data collection and analysis and manuscript preparation, YM participated in the data collection and analysis, XQ participated in the data analysis and manuscript preparation, KD participated in the study design, QJ participated in the data collection, ZZ participated in the study design and manuscript preparation, and MY participated in the study design and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board (Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine). The informed consent was obtained for each patient.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, K., Mao, Y., Qu, X. et al. High-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy for nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Orthop Surg Res 13, 25 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0705-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0705-x