Abstract

Background

At present, traumatic atlantoaxial dislocation or C2-3 instability complicating odontoid fractures remains rarely reported. The aim of this study was to further investigate the surgical treatment strategies and curative effects for odontoid fractures combined with instability of adjacent segments.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of 12 patients (5 females and 7 males; age, 21-65 years) who underwent internal fixation for odontoid fractures (type II and shallow type III) and atlantoaxial instability in 6 cases, C2-3 instability in 4 cases, simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability in 2 cases between January 2005 and June 2012. Accordingly, individualized surgeries were performed. Fracture healing and bone fusion were determined on X-ray scan. Upper limbs, lower limbs and sphincter functions were assessed using the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score. Frankel grading system was used for the evaluation of neurological situation.

Results

Mean follow-up time of all 12 cases was 16.4 months (range, 12 to 48 months). Odontoid fracture healing was obtained in all patients within 9 months, and graft fusion was achieved within 6 months. JOA score was significantly improved from 6.3 ± 3.1 preoperatively to 11.1 ± 4.6 at 12 months after operation (P = 0.007), with 50.5 ± 25.7% recovery rate and 66.7% excellent and good rate. Except one patient still had Frankel grade B neurological injury at 12 months after surgery, the other patients improved their neurological situation (at 1 grade in Frankel scale). One patient developed wound fat liquefaction which resolved by changing the dressing. Cerebrospinal fluid leakage occurred in three patients, which resolved after the continuous drainage for 2 days.

Conclusions

According to the characteristics of odontoid fractures, the individualized operative procedure should be performed, resulting in high fracture healing rate, function recovery rate, and less, transient complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anatomically, the odontoid process, with its attached ligamentous ring formed ventrally by the anterior arch of the atlas and posteriorly by the transverse atlantal ligament, is the keystone to maintain the stability of atlantoaxial articulation [1],[2]. Any disruption of the odontoid process or the ligaments will predispose the patients to atlantoaxial joint instability (e.g., dislocation or subluxation) which further causes compression of the spinal cord, nerve root, or vertebral artery [3], ultimately leading to neurological damages or death [4]. In addition, recent studies also reported the cases who sustained odontoid fractures combined with instability of C2-3 [5]-[7]. The multiple fractures make their management challenging for surgeons. At present, traumatic atlantoaxial dislocation [8]-[10] or spondylolisthesis of C2-3 [5]-[7] complicating odontoid fractures remains rarely reported. This study was a retrospective review of 12 patients who suffered odontoid fractures combined with atlantoaxial instability, C2-3 instability, or C1-2 and C2-3 simultaneous instability. We aimed to discuss the management of these types of injury based in our experience.

Materials and methods

Patients

From January 2005 to June 2012, 12 patients (7 males and 5 females; average age, 36 years, range, 21-65 years) suffered odontoid fractures combined with instability of adjacent segments and underwent internal fixation in our hospital. The combined instability of adjacent segments included atlantoaxial instability in 6 cases (atlantoaxial dislocation/subluxation in 5 cases and atlas fracture in 1 case), C2-3 instability in 4 cases (C2-3 disc injury in 2 cases, Hangman fracture in 1 case and C3 fracture in 1 case), and C1-2 and C2-3 instability in 2 cases (atlantoaxial dislocation with C2-3 disc injury in 1 case and atlas fracture with C2/3 dislocation in 1 case) (see Table 1). The injury mechanisms were traffic accidents in 8 cases and falling from a height in 4 cases. The upper cervical spine deformities and degenerative diseases were not involved in them. The mainly clinical symptoms were occipital pain, limited neck mobility, torticollis with limited neck movements, numbness in the upper extremity, inability to exercise for lower extremity, and other neurological symptoms. Odontoid fractures were diagnosed by anteroposterior, lateral, and open mouth (atlantoaxial) X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scanning, three-dimensional (3-D CT) scanning, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). There were 9 type II and 3 shallow type III fractures according to the classification of Anderson and D’Alonzo [11]. The type II and rostral `shallow’ type III odontoid fractures represent highly unstable entities [12]. Twelve patients manifested nerve injury (Frankel grade A in 1 case, grade B in 2 cases, grade C in 3 cases, and grade D in 6 cases) [13]. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, no further approvals of the patient or the local ethics committee were necessary.

Surgical strategies

All the 12 patients underwent internal fixation surgery at 1-7 days after injury, with an average of 3.2 days. According to the characteristics of odontoid fractures and the stable condition of atlantoaxial joint and C2-3, we applied different surgical methods as follows (see Table 1). The patients with simple odontoid fractures were treated by anterior odontoid screw fixation. If it was difficult for odontoid screw placement, posterior fixation was recommended. For odontoid fractures with atlantoaxial dislocation or atlas fractures, posterior atlantoaxial pedicle screw fixation or occipital cervical fusion was carried out if clinically indicated. For odontoid fractures with C2-3 disc injury/Hangman fracture, the anterior C2/3 discectomy, interbody fusion, and anterior cervical plate fixation were used. For odontoid fractures with C3 fractures, posterior C2-3 pedicle screw or lateral mass screw fixation were elected. For odontoid fractures with C1/2 and C2/3 instability, posterior C1-3 pedicle screw/lateral mass screw fixation or combined with anterior surgery was employed. If atlantoaxial pedicle screw placement was difficult, occipitocervical fusion was used. Besides, no significant transverse ligament rupture was observed via MRI in six cases with odontoid fractures and atlantoaxial dislocation/fracture atlas. Thus, interbody fusion was not performed for them. The remaining patients underwent anterior and/or posterior interbody fusion.

After operation, a drainage tube was placed for 24 to 48 h and antibiotics were routinely used for 1 to 3 days. At 12-14 days after operation, the sutures were removed and a plastic cervical gear was used for protection for 3 months. Follow-up visits were scheduled at 6 weeks, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery.

Outcome measures

Fracture healing was defined as trabecular bridging the fracture and faint fracture line on the cervical spine X-ray [14],[15]. Bone fusion was judged by less than 2° of movement between the spinous processes on flexion-extension lateral radiographs [16]. Movement of ≥2° on flexion/extension radiographs was considered and regarded as a pseudarthrosis [17]. If pseudarthrosis could not be identified or excluded, CT scan was performed to evaluate about fusion. The Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) scoring system for cervical myelopathy [18] (Table 2) was used to evaluate the treatment effects at 12 months after surgery compared with before operation. Recovery rate was calculated by the following formula: (postoperative score − preoperative score) / (17 [full score] - preoperative score) / 100%. A recovery rate greater than 75% was graded as excellent, 50% to 75% as good, 25% to 50% as fair, and less than 25% as poor [19].

Statistical methods

All data were analyzed by Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington) and using SPSS10.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The difference between preoperative and postoperative JOA score was analyzed by paired t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Mean follow-up time of all 12 cases was 16.4 months (12 to 48 months). All the preoperative symptoms, including occipital pain, limited neck activity, and torticollis were favorably resolved after operation. On X-ray scan, odontoid fracture union was obtained in all patients within 9 months and bone fusion was achieved within 6 months, with an average of 5.3 months. For the 6 cases without interbody fusion, the implants were removed after an average of 9 months in order to restore atlantoaxial rotation function. The straight alignment of the cervical spine was maintained throughout the follow-up period. No internal fixation loosening, extrusion or breakage, secondary vertebral artery, or nerve damage was observed. One patient developed wound fat liquefaction which was resolved by changing the dressing. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage occurred in three patients, which was healed after the continuous drainage for 2 days. JOA score was significantly improved from 6.3 ± 3.1 preoperatively to 11.1 ± 4.6 at 12 months after operation (P = 0.007), with 50.5 ± 25.7% recovery rate and 66.7% excellent and good rate. Except 1 patient still had Frankel grade B neurological injury at 12 months after surgery; the other patients improved their neurological situation (see Table 1). The typical cases are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

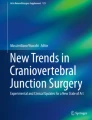

A 34-year-old male patient developed pain symptoms, limited neck movement, and numbness of his two upper extremities after traffic accidents. CT scanning (A) and 3-D CT (B) indicated fractures of the odontoid process of the axis and C1 before operation. Anteroposterior (C) and lateral (D) cervical spine X-ray scanning showed a fracture line in the odontoid anterior after anterior screw and posterior atlantoaxial pedicle screw fixation. 3-D CT showed bone fusion (E) and fracture healing (F) at 6 months after operation.

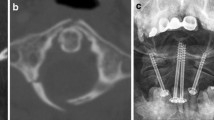

A 43-year-old male patient developed pain symptoms and paralysis of two lower extremities by traffic accidents. CT scanning indicated fractures of the odontoid process of the axis (A), combined with C1-2 and C2-3 dislocation (B). Anteroposterior (C) and lateral (D) cervical spine X-ray scanning showed excellent reduction after posterior C1-2 cervical pedicle screw and C3 lateral mass screws fixation. At 1 year after operation, the anteroposterior (E) and lateral (F) cervical spine X-ray scanning suggested bone fusion and no displacement of the implant.

Discussion

Odontoid fracture is a common traumatic upper cervical spine injury, accounting for 10%-14% of all cervical spine fractures [20]. However, the combination of atlantoaxial instability, C2-3 instability, or simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability with odontoid fractures is rare. In this study, we reported the individualized operative procedures for those patients and obtained the excellent outcome.

Anterior odontoid screw fixation is an effective surgical approach for type II and type III odontoid fractures. This method can provide immediate stabilization, cause less postoperative pain, require no bone graft and preserves normal atlantoaxial rotational motion [21],[22]. Therefore, anterior odontoid screw fixation was preferentially considered for our patients. However, if only the odontoid fractures were reduced, the remaining atlantoaxial, C2-3, or simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability could lead to high cervical spinal cord injury, resulting in quadriplegia or even death. Hence, we suggest to simultaneously restoring C1/2/3 stability and odontoid fractures.

Due to the ease of dissection, the posterior approach has been commonly used to stabilize the C1-C2. Previous studies have demonstrated that pedicle screws can maintain a higher rotational and lateral bending stiffness and withstand higher toggle forces (or pullout strength) compared to the intralaminar screws [23], pars screws [24],[25], and lateral mass screws [26]. Thus, pedicle screws may be the most biomechanically stable for atlantoaxial fixation. In this study, we also attempted to reduce the atlantoaxial dislocation or subluxation through posterior pedicle screws fixation and achieved the favorable outcomes, with the highest recovery rate up to 81.8% and without complication (e.g., internal fixation loosening, extrusion, or breakage).

If it is impossible to place screws into C1-C2 due to atlas fracture, an occipitocervical fixation is usually advocated [9],[27]. However, this approach does not provide good exposure of the articular processes due to the anatomical characteristics of occipitocervical region, and the dura is easily to be injured during surgery, leading to the development of CSF leakage [9],[28]. In this study, one patient underwent occipitocervical fusion and presented postoperative CSF leakage. However, this complication was transient and resolved after the continuous drainage for 2 days.

It is technically feasible to treat C2-C3 instability by anterior C2-3 discectomy followed by an interbody fusion and anterior cervical plate fixation or posterior C2-3 pedicle screw or lateral mass screw fixation [6],[29],[30]. However, anterior stabilization in these injuries may be mandatory from a biomechanical analysis [31]. The anterior approach not only clears the damaged disc directly to relieve spinal cord compression, restore spinal sequence, and reconstruct C2/3 stability but also causes less injuries to spinal cord and artery [32]. If spinal cord compression is from the posterior, a posterior approach should be performed. In the present study, three patients underwent anterior cervical plate fixation and one underwent posterior C2-3 pedicle screw and lateral mass screw fixation. Although the fractures were all healed after 6 months, the JOA (7.1% recovery rate) and Frankel grade (still B) were not significantly improved in the patient with Hangman’s fracture. We believe that this may be attributed to the serious nerve injury preoperatively and thus suggest the surgery should be performed as early as possible. In addition, fat liquefaction was observed in one patient, which delayed the fracture healing and bone fusion time.

We also reported two patients who sustained simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability with odontoid fractures, indicating that the C1-3 should be fixed. Previous study recommended to use the C1-3 lateral mass screw fixation [33] which provides a better immobilization, anti-fatigue, and anti-subsidence effects. However, this method is difficult to operate and requires imaging equipment to monitor, likely resulting in vertebral artery injury. However, no bleeding or infection was observed in our two patients, but postoperative CSF leakage occurred. We speculate that this may result from the mesh-like holes in the dura because of the long-term severe compression [28].

However, the study has some potential limitations. Firstly, as a retrospective study, patients were not randomly assigned to a surgical procedure. The choice of surgery might be biased by the surgeons’ preference based on the preoperative condition of the patient. Secondly, because the combination of atlantoaxial instability, C2-3 instability, or simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability with odontoid fractures is rare, it was difficult to obtain a sufficient number of patients. Thirdly, the follow-up period was short. Therefore, future studies with large sample size and longer-term monitoring need to be performed to verify our results.

Conclusions

Overall, our study reported cases who suffered odontoid fractures combined with atlantoaxial instability, C2-3 instability, or simultaneous C1-2 and C2-3 instability and investigated the individualized operative procedures for them. Although there were transient complications (e.g., CSF leakage or fat liquefaction) postoperatively, all the fractures were favorably healed, the JOA and neurological situation were significantly improved. These indicate that our surgical strategies may be reasonable, but further randomized controlled studies with large sample size are still needed to confirm our conclusion.

References

Meng H, Gao Y, Li M, Luo Z, Du J: Posterior atlantoaxial dislocation complicating odontoid fracture without neurologic deficit: a case report and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2014, 43 (7): 1001-1006. 10.1007/s00256-013-1809-y.

Scott EW, Haid RW, Peace D: Type I fractures of the odontoid process: implications for atlanto-occipital instability: case report. J Neurosurg. 1990, 72 (3): 488-492. 10.3171/jns.1990.72.3.0488.

Steel H: Anatomical and mechanical considerations of atlanto-axial articulations. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery-American volume. 1968, Journal Bone Joint Surgery Inc., Needham, MA 02192, 1481-&

Evaniew N, Yarascavitch B, Madden K, Ghert M, Drew B, Bhandari M, Kwok D: Atlantoaxial instability in acute odontoid fractures is associated with nonunion and mortality.Spine J 2014. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.029.,

Blondel B, Metellus P, Fuentes S, Dutertre G, Dufour H: Single anterior procedure for stabilization of a three-part fracture of the axis (odontoid dens and hangman fracture): case report. Spine. 2009, 34 (7): E255-E257. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318195ab2d.

Koller H, Assuncao A, Kammermeier V, Holz U: Simultaneous anterior arthrodesis C2-3 and anterior odontoid screw fixation for stabilization of a 4-part fracture of the axis—a technical description. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006, 19 (5): 362-367. 10.1097/01.bsd.0000204502.99471.9a.

Shinbo J, Sameda H, Ikenoue S, Takase K, Yamaguchi T, Hashimoto E, Enomoto T, Kanazuka A, Mimura M: Simultaneous anterior and posterior screw fixations confined to the axis for stabilization of a 3-part fracture of the axis (odontoid, dens, and hangman fractures: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014, 20 (3): 265-269. 10.3171/2013.12.SPINE12448.

Riouallon G, Pascal-Moussellard H: Atlanto-axial dislocation complicating a type II odontoid fracture. Reduction and final fixation. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014, 100 (3): 341-345. 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.12.026.

Moreau P, Nguyen V, Atallah A, Kassab G, Thiong’o M, Laporte C: Traumatic atlantoaxial dislocation with odontoid fracture: a case report. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012, 98 (5): 613-617. 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.03.012.

Spoor AB, Diekerhof CH, Bonnet M, Öner FC: Traumatic complex dislocation of the atlanto-axial joint with odontoid and C2 superior articular facet fracture. Spine. 2008, 33 (19): E708-E711. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817c140d.

Anderson LD, D’ALONZO RT: Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1974, 56 (8): 1663-1674.

Wang J, Zhou Y, Zhang ZF, Li CQ, Zheng WJ, Liu J: Comparison of percutaneous and open anterior screw fixation in the treatment of type II and rostral type III odontoid fractures. Spine. 2011, 36 (18): 1459-1463. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181f46ee8.

Frankel H, Hancock D, Hyslop G, Melzak J, Michaelis L, Ungar G, Vernon J, Walsh J: The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Spinal Cord. 1969, 7 (3): 179-192. 10.1038/sc.1969.30.

Dijkman BG, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH, Bhandari M: When is a fracture healed? Radiographic and clinical criteria revisited. J Orthop Trauma. 2010, 24: S76-S80. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3181ca3f97.

Bhandari M, Chiavaras M, Ayeni O, Chakraverrty R, Parasu N, Choudur H, Bains S, Sprague S, Petrisor B: Assessment of radiographic fracture healing in patients with operatively treated femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2013, 27 (9): e213-e219. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318282e692.

Hacker RJ, Cauthen JC, Gilbert TJ, Griffith SL: A prospective randomized multicenter clinical evaluation of an anterior cervical fusion cage. Spine. 2000, 25 (20): 2646-2655. 10.1097/00007632-200010150-00017.

Yu S, Li F, Yan N, Yuan C, He S, Hou T: Anterior fusion technique for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a retrospective analysis of surgical outcome of patients with different number of levels fused. PloS one. 2014, 9 (3): e91329-10.1371/journal.pone.0091329.

Takagishi N, Nobuhara K, Fukuda H, Matsuzaki A, Mikasa M, Yamamoto R: Shoulder evaluation sheet. J Jpn Orthop Assoc. 1987, 61: 623-

Kawaguchi Y, Matsui H, Ishihara H, Gejo R, Yasuda T: Surgical outcome of cervical expansive laminoplasty in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine. 2000, 25 (5): 551-555. 10.1097/00007632-200003010-00004.

Debernardi A, D’Aliberti G, Talamonti G, Villa F, Piparo M, Cenzato M: Traumatic (type II) odontoid fracture with transverse atlantal ligament injury: a controversial event. World Neurosurg. 2013, 79: 779-783. 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.01.055.

Song K-J, Lee K-B, Kim K-N: Treatment of odontoid fractures with single anterior screw fixation. J Clin Neurosci. 2007, 14 (9): 824-830. 10.1016/j.jocn.2006.06.016.

Lee S-C, Chen J-F, Lee S-T: Management of acute odontoid fractures with single anterior screw fixation. J Clin Neurosci. 2004, 11 (8): 890-895. 10.1016/j.jocn.2004.03.023.

Lapsiwala SB, Anderson PA, Oza A, Resnick DK: Biomechanical comparison of four C1 to C2 rigid fixative techniques: anterior transarticular, posterior transarticular, C1 to C2 pedicle, and C1 to C2 intralaminar screws. Neurosurgery. 2006, 58 (3): 516-521. 10.1227/01.NEU.0000197222.05299.31.

Su BW, Shimer AL, Chinthakunta S, Salloum K, Ames CP, Vaccaro AR, Bucklen B: Comparison of fatigue strength of C2 pedicle screws, C2 pars screws, and a hybrid construct in C1-C2 fixation. Spine. 2014, 39 (1): E12-E19. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000063.

Dmitriev AE, Lehman RA, Helgeson MD, Sasso RC, Kuhns C, Riew DK: Acute and long-term stability of atlantoaxial fixation methods: a biomechanical comparison of pars, pedicle, and intralaminar fixation in an intact and odontoid fracture model. Spine. 2009, 34 (4): 365-370. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181976aa9.

Fensky F, Kueny RA, Sellenschloh K, Püschel K, Morlock MM, Rueger JM, Lehmann W, Huber G, Hansen-Algenstaedt N: Biomechanical advantage of C1 pedicle screws over C1 lateral mass screws: a cadaveric study. Eur Spine J. 2014, 23 (4): 724-731. 10.1007/s00586-013-3143-4.

Dai L, Yuan W, Ni B, Liu H, Jia L, Zhao D, Xu Y: Surgical treatment of nonunited fractures of the odontoid process, with special reference to occipitocervical fusion for unreducible atlantoaxial subluxation or instability. Eur Spine J. 2000, 9 (2): 118-122. 10.1007/s005860050221.

He B, Yan L, Xu Z, Chang Z, Hao D: The causes and treatment strategies for the postoperative complications of occipitocervical fusion: a 316 cases retrospective analysis. Eur Spine J. 2014, 28 (8): 1-5.

Song J, Taghavi CE, Hsu DW, Song K-J, Song J-H, Lee K-B: Radiological changes in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with cage and plate construct: the significance of the anterior spur formation sign. Spine. 2012, 37 (4): 272-279. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821c3cbf.

Xie N, Khoo LT, Yuan W, Ye X-J, Chen D-Y, Xiao J-R, Ni B: Combined anterior C2-C3 fusion and C2 pedicle screw fixation for the treatment of unstable Hangman’s fracture: a contrast to anterior approach only. Spine. 2010, 35 (6): 613-619. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ba3368.

Arand M, Neller S, Kinzl L, Claes L, Joachim Wilke H: The traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis: a biomechanical in vitro evaluation of an instability model and clinical relevant constructs for stabilization. Clin Biomech. 2002, 17 (6): 432-438. 10.1016/S0268-0033(02)00037-2.

Tuite GF, Papadopoulos SM, Sonntag VK: Caspar plate fixation for the treatment of complex hangman’s fractures. Neurosurgery. 1992, 30 (5): 761-764. 10.1227/00006123-199205000-00019.

Horn EM, Hott JS, Porter RW, Theodore N, Papadopoulos SM, Sonntag VK: Atlantoaxial stabilization with the use of C1-3 lateral mass screw fixation: technical note. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006, 5 (2): 172-177. 10.3171/spi.2006.5.2.172.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our warm thanks to all the authors who contributed to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LW and CL carried out the design and coordinated the study, participated in most of the experiments, and prepared the manuscript. QZ provide assistance in the design of the study, coordinated and carried out all the experiments, and participated in manuscript preparation. JWT provided assistance for all experiments. All authors have read and approved the content of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, L., Liu, C., Zhao, Qh. et al. Outcomes of surgery for unstable odontoid fractures combined with instability of adjacent segments. J Orthop Surg Res 9, 64 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-014-0064-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-014-0064-9