Abstract

Background

There have been major improvements in the trauma system and injury prevention in Al-Ain City. We aimed to study the impact of these changes on the incidence, pattern, injury severity, and outcome of hospitalized motorcycle-related injured patients in Al-Ain City, United Arab Emirates.

Methods

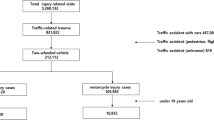

This is a retrospective analysis of two separate periods of prospectively collected data which were retrieved from Al-Ain Hospital Trauma Registry (March 2003 to March 2006 compared with January 2014 to December 2017). All motorcycle-injured patients who were admitted to Al-Ain Hospital for more than 24 h or died in the Emergency Department or after hospitalization were studied.

Results

The incidence of motorcycle injuries dropped by 37.1% over the studied period. The location of injury was significantly different between the two periods (p = 0.02, Fisher's exact test), with fewer injuries occurring at streets/highways in the second period (69.1% compared with 85.3%). The anatomical injury severity of the head significantly increased over time (p = 0.03), while GCS on arrival significantly improved (p < 0.0001), indicating improvements in both prehospital and in-hospital trauma care. The mortality of the patients significantly decreased (0% compared with 6%, p = 0.002, Fisher's exact test).

Conclusions

The incidence of motorcycle injuries in our city dropped by almost 40% over the last 15 years. There was a significant reduction in the mortality of hospitalized motorcycle-injured patients despite increased anatomical severity of the head injuries. This is attributed to improvements in the trauma care system, including injury prevention, and both prehospital and in-hospital trauma care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Road traffic collisions (RTCs) are a major persistent public health problem. Out of 1.35 million deaths worldwide, 28% were caused by motorized 2–3 wheelers [1]. Motorized 2–3 wheelers account for 1.6% of all registered vehicles in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) [1]. During 2016–2017, they caused 6% of road traffic deaths in the UAE and 2% in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi [1, 2]. Motorcycle riders are thirty times more likely to die in RTCs compared with other road users because of the high energy transfer to their exposed bodies when colliding with high speed [3, 4]. This causes severe head injuries and increases death [4,5,6,7,8]. Motorcycle-related injuries had the highest mortality of hospitalized trauma patients in our city, of whom more than 40% had head injuries [6].

Al-Ain City is growing rapidly (65% growth over the last 15 years). It currently has a population of around three quarters of a million [9,10,11]. Its main public hospital (Al-Ain Hospital) had treated around 80% of the trauma patients of our city before the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020), after which it was allocated to treat only COVID-19 patients [12, 13]. Improving trauma systems reduces trauma mortality [14,15,16]. A trauma system is defined as a “preplanned, organized and coordinated injury-control effort in a defined geographic area” [17]. In 2001, a Trauma Group was established in Al-Ain City with a clear preplanned, organized and coordinated effort to improve trauma outcomes. Since then, there have been major developments in the trauma system in our city including injury prevention, prehospital care, in-hospital trauma management, trauma registries, trauma research and trauma education. This included establishing Al-Ain Hospital Trauma Registry [18, 19] which generated significant amount of useful data on trauma management and epidemiology that resulted in numerous high-quality scientific publications. These publications were used, through the media, to promote and improve road, work-related, and home safety [20, 21] as a step toward establishing a trauma system [22]. Injury prevention interventions included installation of speed cameras, high penalties for violations, and enforcing labor safety [23,24,25]. Educational activities included establishing the ATLS [26] and Point-of-Care Ultrasound (POCUS) courses [27] which became an integral part of our clinical practice [28]. Improvements occurred in the prehospital transport system, and in-hospital trauma management with increased number of EMS trained staff [2], mandatory ATLS training for trauma teams [26], having 24-h angioembolization and interventional radiology, following trauma management updates including hypotensive resuscitation, using POCUS, and damage control surgery [28,29,30].

We have previously shown that the maturity of our trauma system reduced trauma death [16], but we did not study its effects on motorcycle-related injuries. Hereby we aim to study the impact of the trauma system development on the incidence, injury pattern and severity, and outcome of hospitalized motorcycle-injured patients in Al-Ain City, United Arab Emirates.

Patients and methods

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Al-Ain Hospital, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates (AAHEC-03-20-008). Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their caregivers to use the data for this study.

Study design

This is a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data which were retrieved from Al-Ain Hospital Trauma Registry. Data were collected, coded, and entered by full-time trained research fellows and nurses.

Patients

We studied all motorcycle-related injured patients who were admitted for more than 24 h or who died on arrival at the Emergency Department or after hospitalization from March 2003 to March 2006 (first period, 3 years) and January 2014 to December 2017 (second period, 4 years).

Studied variables

Studied variables included demography, location of injury, mode of arrival, vital signs and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) on arrival, severity of the injury of regions by Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), Injury Severity Score (ISS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), length of ICU stay, length of ventilation days, length of hospital stay, and clinical outcome.

Setting

Al-Ain City is the second largest city in the Abu Dhabi Emirate, UAE. The city had about 463,000 residents during the first period [10, 11] and around 767,000 residents during the second period [9]. Al-Ain Hospital is one of the two major public hospitals in Al-Ain City, which treated around 80% of the hospitalized trauma patients during the study periods [12, 13]. It provided a wide range of general and specialized clinical services with 412 beds [31].

Calculations

Since Al-Ain Hospital treated 80% of the RTC injured patients in Al-Ain City during the studied periods [12], the correction factor for this percentage would be 100 divided by 80, which equals 1.25. Accordingly, the standardized incidence rate was calculated as follows: (1.25 × annual patients)/(population/100,000).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as numbers (percentage) for categorical data or median (range) for continuous or ordinal data. Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical data for two independent groups, while Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous or ordinal data of two independent groups. Data were analyzed with the IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). A p value of less than 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

There were 68 patients during the first period and 94 patients during the second period. This gives an annual incidence of 6.2/100,000 population for the first period compared with 3.9/100,000 population for the second period, a reduction of 37.1%. Table 1 shows the demography of the two periods. There was no significant difference in age, gender, nationality, or mode of arrival. Nevertheless, the location of injury was significantly different between the two periods (p = 0.02, Fisher's exact test). There were relatively fewer street/highway injuries during the second period (69.1% compared with 85.3%), while other areas of less speed limits increased like homes (7.4% compared with 0%), workplace (3.2% compared with 0%), and public areas (4.3% compared with 0%).

Table 2 shows the severity markers of injuries. GCS was significantly higher in the second period compared with the first period ((median (range), mean (SD): 15 (5–15), 14.69 (1.52) compared with 15 (3–15), 13.29 (3.69) p < 0.0001) (Fig. 1) despite having significantly higher ISS (median (range): 5 (1–41) compared with 4 (1–29), p = 0.04), and NISS (median (range): 9 (1–41) compared with 5.5 (1–41), p = 0.01. The length of ICU and length of ventilation days significantly decreased in the second period (median (range): 0 (0–32) days compared with 4 (1–19) days, p < 0.0001; 0 (0–32) days compared with 1.5 (0–12) days, p < 0.0001, respectively) (Table 2). Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in the length of hospital stay between the two periods (p = 0.12).

Box-and-whisker plot of Glasgow Coma Scale and Injury Severity Score of hospitalized motorcycle-injured patients during the period 2003–2006 (n = 68) and 2014–2017 (n = 94), Al-Ain Hospital, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates. The box represents the 25th to the 75th percentile IQR. The horizontal line within the box represents the median. p value = Mann–Whitney U test

Table 3 shows the anatomical injured regions and their AIS of the two periods. The second period had a significantly lower percentage of head injuries (19.2% compared with 35.3%, p = 0.03, Fisher's exact test) and a significantly higher percentage of neck injuries (9.6% compared with 0%, p = 0.01, Fisher's exact test). The AIS was significantly higher in both the head and upper extremities during the second period (median (range: 3 (1–5) compared with 1.5 (1–4), p = 0.03), and median (range): 2 (1–3) compared with 1 (1–2), p < 0.0001, respectively). The mortality significantly decreased during the second period (0% compared with 5.9%, p = 0.002, Fisher's exact test) (Table 2).

Discussion

Our study has shown a significant improvement in the outcome of hospitalized motorcycle-related injured patients over the last 15 years. The anatomical injury severity of the head doubled while GCS on arrival improved. This indicates better prehospital and in-hospital trauma care. The mortality dropped from 6% to none. Furthermore, the incidence of motorcycle-related injuries dropped by almost 40% in our city indicating improvements in the injury prevention in our setting. These findings highlight the impact of the development of our trauma system in reducing the injury incidence and improving the clinical outcomes of motorcycle-related injured patients.

Globally, motorcycle-related deaths are quarter of all RTC deaths [1, 32,33,34,35]. It is expected to increase by 11% worldwide over the coming 10 years [36]. The United Nations' global aim was to reduce road deaths by half over 2010 to 2020 [37]. Interestingly, this was achieved in our setting [14, 38, 39] but not globally [40]. The effect size and time of improvement vary between different countries [38, 39]. The effect size in our study is large compared with a multicenter study from Israel which showed reduced mortality by 43% [14]. However, our study stemmed from a single hospital. These results can be attributed to improvements in the EMS prehospital care in the Abu Dhabi Emirate [14, 41], which was evidenced by the improved GCS of injured patients on arrival. The reduced mortality despite the increased anatomical severity of the head injury reflects the improved trauma care within our hospital over the last 15 years. These developments include establishing a trauma team that attend with every major trauma, following a trauma management protocol, a 24 h availability of a 16-slice CT scanner and radiologist adjacent to the Emergency Department, development of a trauma CT protocol, availability of 24/7 angioembolization suite run by expert interventional radiologists, presence of an on-call neurosurgical team, establishing an expanded state-of-the-art intensive care unit that follow well-developed guidelines, collecting data on trauma management, continuous clinical audit, and following a quality improvement program.

Over the last two decades, there have been tremendous improvements in injury prevention measures in the UAE. These included enforcement of safety regulations (such as helmet and speed law enforcement), use of safety devices (like helmet usage), installation of road speed cameras, penalties on speeding violations, and educational programs [1, 23, 24, 32,33,34]. This explains the reduction of the percentage of head injuries in the second period by 25% in our study. Although our city previously used motorcycles less than four-wheel vehicles [6, 42], we have observed their recent increase as a cheap transportation and food delivery tool. Figure 2 compares motorized 2–3 wheelers mortality rate, standardized number of motorized 2–3 wheelers, and helmet law enforcement between UAE and other high-income countries [1, 32,33,34]. The motorcycle-related death rate increased sharply in the UAE from 2013 to 2016, which cannot be explained by the minimum increase in the number of motorcycles used in the UAE (Fig. 2). Modernization, improvement, and maturity of our trauma system in all its components contributed to the improved clinical outcome in the current study [16]. The increased severity of head injuries in our study may indicate low helmet compliance, low-quality helmets, or improperly fastened helmets [7, 43, 44]. Collisions became less in high-speed streets/highways and increased in low-speed residential areas, which may explain this finding because riders may be less careful in using their helmets in these areas. Developing an injury prevention strategy to address the concerns regarding the quality of the helmets and collisions in the residential areas is important.

Comparison of motorized 2–3 wheelers death rate/100,000 population (A), motorized 2–3 wheelers/100,000 population (B), and helmet law enforcement (on a scale of 0 to 10) (C) 2007–2016 between UAE (yellow circles) and high-income countries (white circles). Data were collected and analyzed by the authors. Source: WHO Global status report on road safety 2007–2016 published over 2009–2018 [1, 32,33,34]

It may be surprising to notice that around 7% of motorcycle-related injuries in our city occurred at homes in the second period. Al-Ain City is very unique. It spreads horizontally over a very wide region of 30 × 20 kilometers despite the small number of its population. Houses of residential areas are not allowed to be higher than four floors and they have wide fenced areas around them. These are not public areas and considered legally as part of the homes. Motorcycles which are used for sport activity or food delivery enter within these fences and may cause injuries. Understandably, developing an injury prevention strategy for these specific injuries needs special educational and legal considerations.

Limitations of the study

Our study has certain limitations. First, it is from a single hospital which limits its generalizability in all the UAE. Second, there was a gap in our registry from 2007 to 2014 due to a lack of research funding. Third, data on helmet use and clothing (including boots) on the incident and circumstance that led to the crash were missing in our trauma registry. We did not evaluate other important factors such as rider's behavior, riding experience, motorcycle safety technology (like Anti-Lock Brake systems), biomechanism of injury, and road characteristics to give us more insights into the cause of reduced mortality. Fourth, our study had a small sample size which may cause type II statistical error. Nevertheless, these patients represent the majority of those treated over seven years in a city of three quarter of a million population. Furthermore, this small sample enabled us to collect high-quality prospective accurate data with minimum missing data. Finally, our study did not include patients treated at the emergency department who were discharged home, those with minor injuries who did not seek medical advice, and those who died on the streets; which has the risk of selection bias.

Conclusions

The incidence of motorcycle injuries in our city dropped by almost 40% over the last 15 years. There was a significant reduction in the mortality of hospitalized motorcycle-injured patients despite increased anatomical severity of the head injuries. This is attributed to improvements in the trauma care system, including injury prevention, and both prehospital and in-hospital trauma care.

Availability of data and materials

There are no additional data available to share with the readers. Data can be shared with the Editor of the Journal if requested.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Abbreviate Injury Scale

- EMS:

-

Emergency Medical Service

- GCS:

-

Glasgow Coma Scale

- HICs:

-

High-income countries

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- ISS:

-

Injury Severity Score

- NISS:

-

New Injury Severity Score

- RR:

-

Respiratory rate

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- UAE:

-

United Arab Emirates

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. The Global status report on road safety. Vol. 2, Geneva. 2018. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2018/en/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

Department of Health. Abu Dhabi Health Statistics 2017. 2018. https://www.doh.gov.ae/-/media/Feature/Resources/AbuDhabiHealthStatistics.ashx. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Traffic safety facts 2016 (DOT HS 812 554). 2018. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812492. Accessed 10 Nov 2021.

Lin MR, Kraus JF. A review of risk factors and patterns of motorcycle injuries. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:710–22.

Nzegwu MA, Aligbe JU, Banjo AAF, Akhiwu W, Nzegwu CO. Patterns of morbidity and mortality amongst motorcycle riders and their passengers in Benin-city Nigeria: one-year review. Ann Afr Med. 2008;7:1–12.

Hefny AF, Barss P, Eid HO, Abu-Zidan FM. Motorcycle-related injuries in the United Arab Emirates. Accid Anal Prev. 2012;49:245–8.

Ramli R, Oxley J. Motorcycle helmet fixation status is more crucial than helmet type in providing protection to the head. Injury. 2016;47:2442–9.

Ramli R, Oxley J, Noor FM, Abdullah NK, Mahmood MS, Tajuddin AK, et al. Fatal injuries among motorcyclists in Klang Valley, Malaysia. J Forensic Leg Med. 2014;26:39–45.

Statistics Centre. Statistical Yearbook of Abu Dhabi 2020. 2020. 289 p. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/Book/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed 12 Nov 2021.

Abu-Zidan FM, Abbas AK, Hefny AF, Eid HO, Grivna M. Effects of seat belt usage on injury pattern and outcome of vehicle occupants after road traffic collisions: prospective study. World J Surg. 2012;36:255–9.

Al-Kuwaiti A, Hefny AF, Bellou A, Eid HO, Abu-Zidan FM. Epidemiology of head injury in the United Arab Emirates. Ulus Travma ve Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2012;18:213–8.

AlEassa EM, Al-Marashda MJ, Elsherif A, Eid HO, Abu-Zidan FM. Factors affecting mortality of hospitalized chest trauma patients in United Arab Emirates. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:1.

Abu-Zidan FM, Eid HO. Factors affecting injury severity of vehicle occupants following road traffic collisions. Injury. 2015;46:136–41.

Goldman S, Siman-Tov M, Bahouth H, Kessel B, Klein Y, Michaelson M, et al. The contribution of the Israeli Trauma System to the survival of road traffic casualties. Traffic Inj Prev. 2015;16:368–73.

Nathens A, Jurkovich G, Cummings P, Rivara E, Maier R. The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. J Trauma Nurs. 2000;7:105–6.

Alao DO, Cevik AA, Eid HO, Jummani Z, Abu-Zidan FM. Trauma system developments reduce mortality in hospitalized trauma patients in Al-Ain City, United Arab Emirates, despite increased severity of injury. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:1–6.

Tien H. The Canadian Forces trauma care system. Can J Surg. 2011;54:S112–7.

Shaban S, Ashour M, Bashir M, El-Ashaal Y, Branicki F, Abu-Zidan FM. The long-term effects of early analysis of a trauma registry. World J Emerg Surg. 2009;4:42.

Shaban S, Eid HO, Barka E, Abu-Zidan FM. Towards a national trauma registry for the United Arab Emirates. BMC Res Notes. 2010;3:187.

Matthew Chung. New push to require rear seat belts. The National, September 02, 2009. https://www.thenational.ae/uae/transport/new-push-to-require-rear-seat-belts-1.541316. Accessed 31 March 2022.

Matt Kwong and Suryatapa Bhattacharya. Research highlights danger to labourer The National, October 02, 2009. https://www.thenational.ae/uae/health/research-highlights-danger-to-labourers-1.534744. Accessed 31 March 2022.

Olivia Olarte. Trauma system in the pipeline in Abu Dhabi. Khaleej Times, October 25, 2011. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/article/trauma-system-in-the-pipeline-in-abu-dhabi. Accessed 31 March 2022.

Grivna M, Aw TC, El-Sadig M, Loney T, Sharif AA, Thomsen J, et al. The legal framework and initiatives for promoting safety in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2012;19:278–89.

United Arab Emirates Government Portal. Road safety. u.ae/en/information-and-services/justice-safety-and-the-law/road-safety. Accessed 31 March 2022.

United Arab Emirates Government Portal. Health and safety at work place. u.ae/en/information-and-services/jobs/health-and-safety-at-workplace. Accessed 31 March 2022.

Abu-Zidan FM, Mohammad A, Jamal A, Chetty D, Gautam SC, van Dyke M, Branicki FJ. Factors affecting success rate of Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) courses. World J Surg. 2014;38:1405–10.

Abu-Zidan FM, Dittrich K, Czechowski JJ, Kazzam EE. Establishment of a course for Focused Assessment Sonography for Trauma. Saudi Med J. 2005;26:806–11.

Abu-Zidan FM. Optimizing the value of measuring inferior vena cava diameter in shocked patients. World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5:7–11.

Bashir MM, Abu-Zidan FM. Damage control surgery for abdominal trauma. Eur J Surg Suppl. 2003;588:8–13.

Saleh A, Potemkowski A, Abu-Zidan FM. Endovascular aortic stent graft repair for blunt traumatic thoracic aortic transection. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:847–8.

Abu Dhabi Health Services Company—SEHA. SEHA 2019 annual report: healthcare for a changing world. 2019. https://sandpaperme.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/SEHA_English_DIGITAL1.pdf. Accessed 25 Nov 2021.

World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety. Vol. 15, Geneva. 2015. https://www.afro.who.int/sites/default/files/2017-06/9789241565066_eng.pdf. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety: supporting a decade of action. Geneva. 2013. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2013/en/%5Cnhttp://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/road_safety_status/2015/en/. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

World Health Organization. Global status report on road safety: time for action [Internet]. Geneva. 2009. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44122/9789241563840_eng.pdf; jsessionid=80D4774FE6C0CA3666010581CD4B9C1F?sequence=1. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

World Health Organization. Powered two- and three-wheeler safety: a road safety manual for decision-makers and practitioners. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1081388/retrieve. Accessed 27 Oct 2021.

Inada H, Li Q, Bachani A, Hyder AA. Forecasting global road traffic injury mortality for 2030. Inj Prev. 2019;66:1–5.

United Nations. Global plan for the Decade of Action for Road Safety 2011–2020. Geneva: WHO. 2010. p. 25. http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:Global+Plan+for+the+Decade+of+Action+for+Road+Safety+2011-2020#0. Accessed 28 Oct 2021.

Moore L, Champion H, Tardif PA, Kuimi BL, O’Reilly G, Leppaniemi A, et al. Impact of trauma system structure on injury outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2018;42:1327–39.

Vali Y, Rashidian A, Jalili M, Omidvari AH, Jeddian A. Effectiveness of regionalization of trauma care services: a systematic review. Public Health. 2017;146:92–107.

Yasin YJ, Grivna M, Abu-Zidan FM. Motorized 2–3 wheelers death rates over a decade: a global study. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17:7.

Fares S, Irfan FB, Corder RF, Al Marzouqi MA, Al Zaabi AH, Idrees MM, et al. Emergency medicine in the United Arab Emirates. Int J Emerg Med. 2014;7:1–8.

Eid HO, Barss P, Adam SH, Torab FC, Lunsjo K, Grivna M, et al. Factors affecting anatomical region of injury, severity, and mortality for road trauma in a high-income developing country: lessons for prevention. Injury. 2009;40:703–7.

Yu WY, Chen CY, Chiu WT, Lin MR. Effectiveness of different types of motorcycle helmets and effects of their improper use on head injuries. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:794–803.

Kim S, Ro YS, Shin SD, Song KJ, Hong KJ, Jeong J. Preventive effects of motorcycle helmets on intracranial injury and mortality from severe road traffic injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36:173–8.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

There was no funding for this research study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJY, HOE, DOA, MG, and FAZ contributed to the study conception and design. YJY, HOE, DOA, and FAZ contributed to the acquisition and coding of data. YJY and FAZ analyzed the data. YJY and FAZ wrote the paper. FAZ critically edited the paper. YJY, HOE, DOA, MG, and FAZ critically reviewed the manuscript. FAZ revised the manuscript and responded to the reviewers. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Al-Ain Hospital, Al-Ain, United Arab Emirates (AAHEC-03-20-008). Written informed consents were taken from the patients or their caregivers to use their data in research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yasin, Y.J., Eid, H.O., Alao, D.O. et al. Reduction of motorcycle-related deaths over 15 years in a developing country. World J Emerg Surg 17, 21 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00426-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-022-00426-y