Abstract

Background

The effects of obesity on injury severity and outcome have been studied in trauma patients but not in those who have experienced a fall. The aim of this study was to compare injury patterns, injury severities, mortality rates, and in-hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) between obese and normal-weight patients following a fall.

Methods

Detailed data were retrieved for 273 fall-related hospitalized obese adult patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 and 2357 normal-weight patients with a BMI <25 kg/m2 but ≥18.5 kg/m2 from the Trauma Registry System of a Level I trauma center between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. We used the Pearson’s chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test, the Mann Whitney U test, and independent Student’s t-test to analyze differences between the two groups.

Results

Analysis of AIS scores and AIS severity scaling from 1 to 5 revealed no significant differences in trauma regions between obese and normal-weight patients. When stratified by injury severity (Injury Severity Score [ISS] of <16, 16–24, or ≥25), more obese patients had an ISS of <16 compared to normal-weight patients (90.5 % vs. 86.0 %, respectively; p = 0.041), while more normal-weight patients had an ISS between 16 and 24 (11.0 % vs. 6.6 %, respectively; p = 0.025). Obese patients who had experienced a fall had a significantly lower ISS (median (range): 9 (1–45) vs. 9 (1–50), respectively; p = 0.015) but longer in-hospital LOS than did normal-weight patients (10.1 days vs. 8.9 days, respectively; p = 0.049). Even after taking account of possible differences in comorbidity and ISS, the obese patients have an average 1.54 day longer LOS than that of normal-weight patients. However, no significant differences were found between obese and normal-weight patients in terms of the New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Trauma-Injury Severity Score (TRISS), mortality, percentage of patients admitted to the ICU, or LOS in the ICU.

Conclusion

Obese patients who had experienced a fall did not have different injured body regions than did normal-weight patients. However, they had a lower ISS but a longer in-hospital LOS than did normal-weight patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Falls are a leading cause of injury and a significant public health issue [1–3]. The incidence of falls that lead to emergency unit admission is growing with the increased size and rapid growth of the geriatric population [4, 5]. In addition, obesity is a worldwide health problem leading to a range of health consequences [6, 7]. While obesity is known to increase the risk for a variety of medical conditions including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiac disease, and pulmonary thromboembolism [8], the effect of obesity on the injury pattern and outcome of trauma patients after a fall remains unclear. Evidence was found that the effect of weight on the risk of falling appeared to be linear; greater obesity was related to greater risk of falling [9–11]. Compared with normal-weight respondents, the odds ratios (OR) for risk of falling were 1.12 (95 % confidence interval [CI] = 1.01–1.24) for obesity Class 1 (BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2), 1.26 (95 % CI = 1.05–1.51) for obesity Class 2 (BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m2), and 1.50 (95 % CI = 1.21–1.86) for obesity Class 3 (BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2) [9]. In addition, obesity was associated with a 25 % higher risk (95 % CI = 1.11–1.41; p < 0.0003) of having fallen in the previous 12 months compared to non-obese individuals [12].

Identification of the high-risk injury patterns and better understanding of the epidemiology and outcome of fall injury in obese patients are important in order to cope with a rising number of obese patients. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the injury characteristics, injury patterns, injury severities, and mortality rates of adult obese patients admitted and treated for fall-related injury in southern Taiwan over a five-year period at a level I trauma center.

Methods

Ethics statement

Approval for this study was obtained from the hospital’s institutional review board (IRB) before its initiation (approval number 103-7110B). Given its observational nature, the requirement for written informed consent from each patient was waived by the IRB.

Study design

This retrospective study was designed to review all 16,548 hospitalized and registered patients added to the Trauma Registry System from January 1, 2009, to December 31, 2013, and select cases that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age ≥ 18 years, (2) BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 for obese patients and BMI < 25 but ≥ 18.5 kg/m2 for normal-weight patients according to the World Health Organization definition [13, 14], and (3) admittance due to a fall accident. The patients who had sustained fall injuries from all fall heights (<1 m, 1–6 m, >6 m) were included, but those who had attempted suicide in the fall or who had non-validated BMI values or incomplete data were excluded.

To compare the injury patterns, mechanisms, severity, and mortality of obese patients with those of normal-weight patients, detailed data were retrieved on age, sex, vital signs in the emergency department (ED), injury mechanism, fall height (<1 m, 1–6 m, >6 m), transportation, injury time, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) upon arrival at the ED, Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) severity score for each body region, Injury Severity Score (ISS), New Injury Severity Score (NISS), Trauma-Injury Severity Score (TRISS), in-hospital length of stay (LOS), LOS in the ICU, and in-hospital mortality. In addition, the pre-existed comorbidities and chronic diesases including diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), coronary artery diseases (CAD), congestive heart failure (CHF), cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) were identified. A blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of 50 mg/dL at the time of arrival at the hospital was defined as the cut-off value according to the legal limit for drivers in Taiwan. The primary outcomes were injury severity scores (i.e., GCS, AIS, ISS, NISS, and TRISS), and the secondary outcomes were LOS, ICU LOS, and in-hospital mortality.

The ORs of the injured regions and associated conditions sustained by obese and normal-weight patients were calculated with 95 % CIs. Data collected regarding the obese and normal-weight population of patients who had experienced a fall were compared using SPSS v.20 statistical software (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Pearson’s chi-squared tests, Fisher’s exact tests, and independent Student’s t-tests were used to analyze data as applicable. The Mann Whitney U test was used to compare the AIS severity scaling from 1 to 5 in each injury region. Ordinal data, like ISS and NISS, is presented as median (range). Data were further analyzed by a multiple linear regression adjusted for the effect of confounding variables (ie, comorbidity and ISS) to show the main effects of obesity on LOS in hospital. All other results are presented as the mean ± standard error.

Results

Injury characteristics

Among the 2630 adult patients with fall accidents, 273 (10.4 %) were obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2), and 2357 (89.6 %) were of normal weight (25 > BMI ≥ 18.5 kg/m2) (Table 1). No statistically significant difference regarding sex was found between the obese and normal-weight patients. The mean ages of the obese and normal-weight patients were 60.6 ± 16.8 and 65.7 ± 17.1 years, respectively (p <0.001). There were significant higher incidence rates of the pre-existed comorbidities and chronic diseases including DM, HTN, and CAD in the obese patients. The majority of patients in both groups fell from a height < 1 m, implying that the majority of the patients sustained a ground-level fall occurring upon walking or with movement; however, this difference in patient number stratified by fall height (<1 m, 1–6 m, >6 m) was not statistically significant.

Injury severity

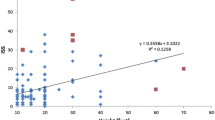

No significant differences were found between obese and normal-weight patients in GCS scores (14.6 ± 1.7 vs. 14.4 ± 2.0, respectively; p = 0.104) and the distribution of the proportion of patients at different levels of consciousness (GCS ≤8, 9–12, or ≥13) (Table 1). Analysis of AIS scores revealed no significant differences in trauma regions between obese and normal-weight patients. Comparison of the composition of AIS severity scaling from 1 to 5 in each region between obese and normal-weight patients also did not show a significant difference (Table 2). A significant difference in ISS was found between obese and normal-weight patients (median (range): 9 (1–45) vs. 9 (1–50), respectively; p = 0.015). When stratified by injury severity (ISS of <16, 16–24, or ≥25), more obese than normal-weight patients had an ISS < 16 (90.5 % vs. 86.0 %, respectively; p = 0.041), while more normal-weight than obese patients had an ISS between 16 and 24 (11.0 % vs. 6.6 %, respectively; p = 0.025). However, no significant difference were found for NISS (median (range): 9 (1–66) vs. 9 (1–75), respectively; p = 0.070), TRISS (0.960 ± 0.112 vs. 0.958 ± 0.085, respectively; p = 0.645), or in-hospital mortality (2.6 % vs. 2.3 %, respectively; p = 0.645). We found that obese patients had a significantly longer average in-hospital LOS than did normal-weight patients (10.1 vs. 8.9 days, respectively; p = 0.049). Because the detected significant higher incidence rates of DM, HTN, and CAD in the obese patients or a higher ISS may be positively correlated to a longer hospital stay, therefore, we performed a multiple linear regression analysis to investigate the effect of obesity, DM, HTN, CAD, and ISS on LOS (days) of these patients. The analysis of variance table (Table 3) indicates that the relationship between obesity and LOS is significant (p = 0.005), LOS in obesity tends to be 1.54 day longer, on average, than that of normal-weight patients, even after taking account of possible differences in comorbidity and ISS. In addition, the relationship between ISS and LOS is highly significant (p < 0.0005), with a one score increase in ISS being associated with an average increase of 0.64 day LOS, after adjusting for obesity and comorbidity. However, no differences were noted in the proportion of obese and normal-weight patients admitted to the ICU as well as LOS in the ICU after stratification into either group of injury severity (ISS of <16, 16–24, or ≥25). In addition, among those who had sustained 3 or more body area injury (AIS ≥3 sites), there were no difference in obese and normal-weight patients admitted to the ICU, LOS in the ICU and in the hospital, and the mortality.

Physiological response & procedures performed at the ED

Upon arrival at the ED, no significant differences were found for GCS of <13, systolic blood pressure (SBP) of <90 mmHg, heart rate of >100 beats/min, or respiratory rates of <10 or >29. Furthermore, no significant differences were found in the odds for requiring procedures, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, chest tube insertion, and blood transfusion, at the ED (Table 4).

Discussion

In a retrospective review of all blunt trauma patients admitted to the ICU at a Level I trauma center, prior study demonstrated that there was no difference between obese and lean patients in the type of traumatic brain injury [15]. Another study demonstrated similar injury patterns of fewer head but more chest and lower extremity injuries [16]. It has also been reported that obese trauma patients sustained more pelvic, rib, and lower extremity fractures but fewer liver injuries, mandibular fractures, and cerebral injuries than those non-obese trauma patients [17]. Based on our analysis of the AIS scores, obese patients presented no significant difference of injuries to body region from normal-weight patients. Comparison of the composition of AIS severity scaling from 1 to 5 in each region also did not show a significant difference between obese and normal-weight patients.

Longer hospitalizations of obese patients result in increased morbidity and are associated with impaired mobility, higher incidence of respiratory complications, more venous thromboembolic events, and higher nosocomial infection rates [18]. For example, obesity resulted in nearly twofold-increased odds for developing cardiac and pulmonary complications after a hip fracture as well as significantly increasing the odds of developing infectious complications (OR 3.8; 95 % CI 1.9–7.6, p < 0.001) [19]. It has been reported that the mean duration of orthopedic surgery in morbidly obese patients was 30 % longer than in non-obese patients [20]. Moreover, medically stable obese patients were found to be almost twice as likely to experience delayed fracture fixation due to preference of the surgeon [20]. In addition, obesity in critically ill patients is significantly related to a prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation and intensive care unit length of stay [21, 22]. In this study, although obese patients had a significant lower ISS than normal-weight patients who had experienced a fall, the obese patients had a significantly longer in-hospital LOS than did normal-weight patients. Even after taking account of possible differences in comorbidity and ISS, the obese patients have an average 1.54 day longer LOS than that of normal-weight patients.

Limitation of this study involves the use of a retrospective design with its inherent selection bias and the lack of available data on the circumstances of the mechanisms of injury. In addition, the patients dead on hospital arrival or accident scene are not included into the Trauma Registry Database, thus creating a selection bias. Moreover, some well-established risk factors, including prior falls, inappropriate use of medications, gait or balance problems, and functional limitations, were not documented and analyzed in this study. Finally, this study is only descriptive and, therefore, unable to assess the effects of any particular treatment intervention; it could only rely on the assumption that assessment and management are uniform between obese and normal-weight populations.

Conclusion

The obese adult patients presented with similar injury to the body region following a fall in comparison with normal-weight patients. The obese patients had significantly lower ISS but significantly longer in-hospital LOS than did normal-weight patients. However, mortality, the percentage of patients admitted to the ICU, and LOS in the ICU exhibited no statistically significant differences between obese and normal-weight patients.

Level of evidence

Epidemiological study, level III.

References

Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51–61.

Rosen T, Mack KA, Noonan RK. Slipping and tripping: fall injuries in adults associated with rugs and carpets. J Inj Violence Res. 2013;5(1):61–9.

Hester AL, Wei F. Falls in the community: state of the science. Clin Interv Aging. 2013;8:675–9.

Meschial WC, Soares DF, Oliveira NL, Nespollo AM, Silva WA, Santil FL. Elderly victims of falls seen by prehospital care: gender differences. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17(1):3–16.

Wendelboe AM, Landen MG. Increased fall-related mortality rates in New Mexico, 1999–2005. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(6):861–7.

Pi-Sunyer FX. The obesity epidemic: pathophysiology and consequences of obesity. Obes Res. 2002;10 Suppl 2:97s–104.

Wang Y, Lobstein T. Worldwide trends in childhood overweight and obesity. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(1):11–25.

Rosenfeld HE, Tsokos M, Byard RW. The association between body mass index and pulmonary thromboembolism in an autopsy population. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57(5):1336–8.

Himes CL, Reynolds SL. Effect of obesity on falls, injury, and disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(1):124–9.

Mitchell RJ, Lord SR, Harvey LA, Close JC. Associations between obesity and overweight and fall risk, health status and quality of life in older people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(1):13–8.

Finkelstein EA, Chen H, Prabhu M, Trogdon JG, Corso PS. The relationship between obesity and injuries among U.S. adults. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(5):460–8.

Mitchell RJ, Lord SR, Harvey LA, Close JC. Obesity and falls in older people: mediating effects of disease, sedentary behavior, mood, pain and medication use. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;60(1):52–8.

Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1995;854:1–452.

Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:i-xii, 1–253.

Brown CV, Rhee P, Neville AL, Sangthong B, Salim A, Demetriades D. Obesity and traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2006;61(3):572–6.

Brown CV, Neville AL, Rhee P, Salim A, Velmahos GC, Demetriades D. The impact of obesity on the outcomes of 1,153 critically injured blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2005;59(5):1048–51. discussion 1051.

Boulanger BR, Milzman D, Mitchell K, Rodriguez A. Body habitus as a predictor of injury pattern after blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1992;33(2):228–32.

Goulenok C, Monchi M, Chiche JD, Mira JP, Dhainaut JF, Cariou A. Influence of overweight on ICU mortality: a prospective study. Chest. 2004;125(4):1441–5.

Belmont Jr PJ, Garcia EJ, Romano D, Bader JO, Nelson KJ, Schoenfeld AJ. Risk factors for complications and in-hospital mortality following hip fractures: a study using the National Trauma Data Bank. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134(5):597–604.

Childs BR, Nahm NJ, Dolenc AJ, Vallier HA. Obesity is associated with more complications and longer hospital stays after orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(11):504–9.

Akinnusi ME, Pineda LA, El Solh AA. Effect of obesity on intensive care morbidity and mortality: a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(1):151–8.

Mica L, Keel M, Trentz O. The impact of body mass index on the physiology of patients with polytrauma. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):722–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JFC revised the manuscript; CSR drafted the manuscript; HTL wrote the manuscript; SCW, YCC, and SYH performed the analysis and edited the tables; HYH revised and proofread the manuscript; CHH designed the study, contributed to the data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Jung-Fang Chuang and Cheng-Shyuan Rau contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuang, JF., Rau, CS., Liu, HT. et al. Obese patients who fall have less injury severity but a longer hospital stay than normal-weight patients. World J Emerg Surg 11, 3 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-015-0059-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-015-0059-9