Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to compare carbon-ion (C-ion), proton and photon radiotherapy (RT) plans with regard to dose reduction of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract by using a greater omentum spacer (GO spacer).

Methods

We retrospectively retrieved data for ten patients who received the GO spacer as surgical spacer placement for abdominal and pelvic tumors. Simulation plans were created on pre-spacer Computed Tomography (CT) and post-spacer CT for C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT to compare the dose of the GI tract. The plans were normalized so that at least 95% of the planning target volume (PTV) received 70 Gy (relative biological effectiveness equivalent) delivered in 35 fractions. All plans were created with the lowest possible dose to the GI tract under conditions that meet the dose constraints for the PTV and spinal cord (maximum dose < 45 Gy). The part of the GI tract to be evaluated was defined as that most adjacent to the PTV. C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans were calculated by a spot scanning technique, and photon RT plans were calculated employing by fixed-field intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

Results

D2 cc and V10–70 of the GI tract were significantly lower on post-spacer plans than on pre-spacer plans for all three RT modalities. Regarding post-spacer plans, D2 cc of the GI tract was significantly lower on C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans than on photon RT plans (C-ion vs photon p = 0.001, proton vs photon p = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference between C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans for D2 cc of the GI tract (C-ion vs proton p = 0.992). In the photon RT plan for one patient, D2 cc of the GI tract did not meet < 50 Gy.

Conclusions

The GO spacer shows a significant dose reduction effect on the GI tract.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

In radiotherapy (RT) for abdominal and pelvic tumors, the distance between the tumor and gastrointestinal (GI) tract is important for dose prescription. The tolerable dose for the small bowel and large intestine was typically considered to be about 50 Gy [1]. Several previous studies have reported the utility of particle therapy to treat various malignant tumors, including chordoma, rectal cancer (postoperative pelvic recurrence), hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate cancer [2,3,4]. In these reports, the prescription dose for tumors generally exceeded 50 Gy. In other words, the curative dose for abdominal and pelvic tumors is considered to be higher than the tolerable dose for the GI tract. Therefore, when the tumor is adjacent to the GI tract, it is difficult to deliver a curative dose to the tumor without damaging the adjacent GI tract. The use of a spacer enables separation of the tumor and the GI tract. Thus, by using a spacer, it is possible to safely increase the dose delivered to the tumor and to achieve a curative dose for the tumor.

Methods involving injection of hyaluronic acid or other gels to separate the prostate and rectum were used in previous studies on treatment of prostate cancer [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. Several studies have also been reported that it is possible to safely increase the dose delivered to the tumor by using polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-tex®) sheets, a tissue expander and the omentum as the spacer [13,14,15,16,17].

Particle therapy has more focused effects than photon RT on target tissues because particle therapy such as carbon-ion (C-ion) RT and proton RT has a Bragg peak. As described above, several studies have shown the utility of particle therapy for treatment of various malignant tumors including chordoma, rectal cancer (postoperative pelvic recurrence), hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate cancer [2,3,4]. Recently, the use of particle therapy for abdominal and pelvic tumors has been increasing. However, there has been no study in which the dose distributions of C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT for patients with abdominal and pelvic tumors were compared. This study was an in silico planning comparative study that was carried out to compare C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT plans regarding dose reduction of the GI tract by the use of a greater omentum spacer (GO spacer).

Methods

Study population

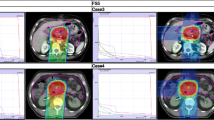

We retrospectively retrieved data for ten patients who received surgical spacer placement for abdominal and pelvic tumors in Southern Tohoku Proton Therapy Center from February 2009 through October 2016. In all patients, the tumor was adjacent to the GI tract, and GO spacer was inserted between the tumor and surrounding GI tract by laparotomy. Simulation plans were created on pre-spacer Computed Tomography (CT) and post-spacer CT for all three RT modalities (i.e., C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT). Post-spacer CT images were taken within 4 weeks after surgery. Pre-spacer CT images were mainly acquired using a 64-row detector CT system (Optima 660, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, USA) or a 4-row detector positron emission tomography (PET)-CT system (Discovery LS, General Electric Medical Systems, Milwaukee, USA), but some pre-spacer CT images were acquired in other facilities (CT details unknown). Post-spacer CT images were acquired using a 16-row detector CT system (Aquilion LB, Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). Figure 1 shows an example of pre-spacer CT and post-spacer CT images. All of the patients were positioned supine. A set of 3–5-mm-thick CT images was taken for pre-spacer CT and a set of 2–5-mm-thick CT images was taken for post-spacer CT.

Target delineation and treatment planning

All contouring and treatment plans were created by one certified radiation oncologist with 6 years of radiation therapy experience and were confirmed by two medical physicists with more than 1 year of C-ion RT experience.

MIM ver. 6.4.6 (MIM Software Inc., Cleveland, OH) was used for contouring. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was delineated as the macroscopic tumor on CT and/or hybrid fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET. The clinical target volume (CTV) was the same as GTV. The planning target volume (PTV) included the CTV with a 7-mm margin for possible positioning errors. Assuming the usage of respiratory gating for upper abdominal tumors, internal margin for compensating respiratory motion was regarded to be sufficiently small. The GI tract (duodenum, small bowel and colon) and spinal cord were defined as organs at risk (OARs). The GI tract was delineated in the range expanded 10 mm to the cranial and caudal sides from the PTV. Clinical delineations that were performed on pre-spacer CT and post-spacer CT by experienced radiation oncologists were used in this study.

C-ion RT plans were calculated on the VQA treatment planning system (TPS) ver. 3.2 (Hitachi, Ltd., Japan). C-ion RT plans were calculated by a spot scanning technique based on irradiation equipment of Heavy-Ion Medical Accelerator in Chiba (HIMAC) [18]. The single-field uniform-dose (SFUD) optimization technique was applied [19]. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) was taken into account using the spread-out Bragg peak (SOBP) concept to calculate the dose in Gy (RBE) based on irradiation equipment of HIMAC [20]. The dose was calculated using a pencil beam algorithm.

Proton RT plans were calculated on the VQA TPS. Proton RT plans were also calculated by a spot scanning technique based on irradiation equipment of Nagoya Proton Therapy Center [21]. The SFUD optimization technique was applied. The dose was calculated using a pencil beam algorithm, assuming an RBE of 1.1 for proton [22].

Photon RT plans were calculated on EclipseTM ver.11.0 (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). Photon RT plans were calculated using fixed-field intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with 10 MV photons. The dose was calculated with the analytical anisotropic algorithm [23].

Seventy Gy (RBE equivalent) delivered in 35 fractions to the PTV was prescribed in all plans. The plans were normalized so that at least 95% of the PTV received the prescribed dose. The dose fraction number in C-ion RT is small, but in order to compare C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT plans, the prescribed dose was unified at 2 Gy (RBE) per fraction. The dose constraint for the spinal cord was maximum dose (Dmax) < 45 Gy. All plans were created with the lowest possible dose to the GI tract under conditions that meet the dose constraint for the PTV and spinal cord. We aimed to satisfy the dose constraints of the minimum dose received by the most exposed 2 cc volume of the organ (D2 cc) of the GI tract < 50 Gy if possible. For each plan, we chose the coplanar beam arrangement that minimizes the dose to the GI tract as much as possible. C-ion RT and proton RT plans consisted of one to three beams, and IMRT plans consisted of three to five beams. The optimal number of beams and beam angles were investigated with pre-spacer plans and post-spacer plans so that the D2cc of the GI tube is minimized in each plan. The same number of beams and the same beam angles were used for C-ion RT and proton RT. All plans of the three RT modalities were calculated with the assumption of using a rotating gantry.

Dose evaluation and statistical analysis

Dose volume histograms (DVHs) were generated for the PTV and all OARs. D98% (minimum dose to ‘hottest’ 98% of the volume), Dmean (mean dose), D50% (median dose), D2% (minimum dose to ‘hottest’ 2% of the volume) and homogeneity index (HI) of the PTV were evaluated on pre-spacer plans and post-spacer CT plans for all three RT modalities. HI was defined by the following equation: HI = (D2%-D98%)/D50%. In this study, the separation distance from the GI tract to the PTV was defined as the shortest distance without overlap by expanding the PTV in three dimensions. In patients with multiple parts of the GI tract adjacent to the PTV, the part of the GI tract with a large overlap volume between the GI tract and the PTV on pre-spacer CT images was selected for evaluation. The relationship between D2 cc of the GI tract and separation distance from the GI tract to the PTV was evaluated on post-spacer plans.

MIM was used for dose evaluation. We tested the differences in mean values of D2 cc of the GI tract, V10, V15, V20, V25, V30, V35, V40, V45, V50, V55, V60, V65 and V70 (Vx was used to mean the volumes at least received x Gy) of the GI tract and HI of the PTV on pre-spacer CT and post-spacer CT images for all three RT modalities. These values were analyzed statistically by Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Because the presented sample size is very small, we performed a cross validation test using the leave-one-out method on D2 cc and Vx of the GI tract that showed significant differences in Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver.23 (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Tumor localization in patients 1–5 was around the liver and that in patients 6–10 was in the pelvic region.

For each plan, all DVHs for the PTV and spinal cord met constraints respectively. Differences in plan parameter (mean (SD)) for all three RT modalities are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in HI of the PTV between pre-spacer plans and post spacer plans for each of three RT modalities (C-ion p = 0.344, proton p = 0.344, photon p = 0.344). Regarding pre-spacer plans, there was no significant difference in HI of the PTV between all three RT modalities (C-ion vs proton p = 0.754, C-ion vs photon p = 1.000, proton vs photon p = 1.000). Regarding post-spacer plans, there was no significant difference in HI of the PTV between all three RT modalities (C-ion vs proton p = 0.344, C-ion vs photon p = 0.754, proton vs photon p = 0.109). DVHs for the PTV and GI tract on pre-spacer plans and post-spacer plans for all three RT modalities are shown in Fig. 2. Multiple box plots and dose plots (color-coded) of D2cc of the GI tract on pre-spacer plans and post-spacer plans for all three RT modalities are summarized in Fig. 3.The spacer significantly reduced D2 cc of the GI tract for C-ion RT (mean ± SD: 65.4 ± 5.2 Gy vs 6.4 ± 2.4 Gy, p < 0.0001), proton RT (63.3 ± 6.1 Gy vs 6.4 ± 2.9 Gy, p < 0.0001) and photon RT (58.1 ± 4.5 Gy vs 24.4 ± 5.2 Gy, p < 0.0001). Regarding post-spacer plans, D2 cc of the GI tract was significantly lower on C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans than on photon plans (C-ion vs photon p = 0.001, proton vs photon p = 0.002). However, there was no significant difference between C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans for D2 cc of the GI tract (C-ion vs proton p = 0.992).

DVHs for the PTV and GI tract on pre-spacer plans and post-spacer plans with color coding in each case: (a) PTV on pre-spacer/C-ion RT, (b) PTV on pre-spacer/proton RT, (c) PTV on pre-spacer/photon RT, (d) PTV on post-spacer/C-ion RT, (e) PTV on post-spacer/proton RT, (f) PTV on post-spacer/photon RT, (g) GI tract on pre-spacer/C-ion RT, (h) GI tact on pre-spacer/proton RT, (i) GI tact on pre-spacer/photon RT, (j) GI tract on post-spacer/C-ion RT, (k) GI tract on post-spacer/proton RT, and (l) GI tract on post-spacer/photon RT

Multiple box plots and dose plots (color-coded) of D2cc of the GI tract. The box plots represent data with boxes ranging from the 25th to the 75th percentile of the observed distribution of values. Horizontal lines represent the median values for D2 cc of the GI tract. X marks represent the mean values for D2 cc of the GI tract. Whiskers span minimum to maximum observed values with algorithm-defined outliers. Dose plots of D2 cc values for all three modalities in pre-spacer plans and post-spacer plans were color-coded in each case and overlaid on the box plots

The relationship between D2 cc of the GI tract and separation distance from the GI tract to the PTV on post-spacer plans is shown in Fig. 4. As described above, the separation distance from the GI tract to the PTV was defined as the shortest distance without overlap by expanding the PTV in three dimensions. In the photon RT plan for one patient (patient 7), D2 cc of the GI tract did not meet the constraint. Because the separation distance from the GI tract to the PTV on post-spacer plans of patient 7 was not the shortest among all patients, the spacer thickness required to effectively reduce the dose of the GI tract could not be examined. The GTV of that patient was left acetabular and sacral bone metastasis of uterine body cancer. In that patient, the part of the GI tract that was most adjacent to the PTV on post-spacer CT was the sigmoid colon and the separation distance from the PTV to the GI tract was 0.43 cm. In that patient, D2 cc values for the GI tract of C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT were 22.4, 29.2 and 61.3 Gy, respectively. Figure 5 shows dose distributions on post-spacer plans of all three RT modalities for that patient.

V10–70 means ± SD of the GI tract in all patients are summarized in Fig. 6. The spacer significantly reduced V10-V70 of the GI tract for all treatment modalities (all p-values < 0.05). Reduction of V10 and V15 of the GI tract by the spacer was more effectively achieved by C-ion RT and proton RT than by photon RT. However, there was no significant difference between C-ion RT and proton RT in reduction of V20-V70 of the GI tract by the spacer.

Because the presented sample size is very small (only 10 cases), we performed a cross validation test using the leave-one-out method on D2 cc and Vx of the GI tract that showed significant differences in Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test and confirmed the statistical difference (all p-values < 0.05).

Discussion

In previous studies comparing the dose distribution of IMRT techniques for HCC, the conformity index values showed no significant difference between helical-IMRT and static-IMRT (e.g., fixed-field IMRT), but the homogeneity index values significantly improved with helical-IMRT compared with static-IMRT [24, 25]. It has also been reported that the mean dose and low dose region of the normal liver in helical-IMRT were higher than static-IMRT [26]. The purpose of this study was to reduce the dose in the adjacent gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, as photon treatment plans, we chose fixed-field IMRT which was considered to have lower dose to the surroundings, instead of helical-IMRT which was considered to have high homogeneity index values for PTV.

Several studies in which the rectal dose with a spacer for prostate cancer was examined showed that the spacer significantly reduced Dmax, Dmean, and V70 of the rectum [5, 8, 12]. However, there are only case reports of studies showing dose reduction of the GI tract by a spacer for abdominal and pelvic tumors other than prostate cancer [13, 27,28,29]. Therefore, this study is the first study in which the dosimetric effect of a spacer on the GI tract was examined in detail.

We showed that the spacer significantly reduced D2 cc of the GI tract for all three RT modalities. Reduction of D2 cc of the GI tract was more effectively achieved by C-ion RT and proton RT than by photon RT. In the photon RT plan for one patient, D2 cc of the GI tract did not meet the constraint. In that case, it is thought that the PTV was a complicated shape with a large area in contact with the GI tract and that photon RT without a Bragg peak was unable to reduce the dose of the GI tract.

It is noteworthy that there was no significant difference between C-ion RT and proton RT in reduction of D2 cc of the GI tract by the GO spacer. In general, the distal dose to C-ion RT is considered to be higher than that to proton RT due to the fragmentation tail of C-ions [20, 30, 31]. Also, the lateral dose to C-ion RT has been reported to be lower than that to proton RT [32,33,34]. In this study, a comparison of C-ion RT plans and proton RT plans with regard to D2 cc of the GI tract on post-spacer plans showed that there were cases where C-ion RT was superior and there were cases where proton RT was superior. This is thought to depend on the positional relationship of the GI tract and the tumor with respect to the beam angle. However, it is not clear as the number of cases in this study was small.

In this study, the tumor location (upper abdomen vs pelvis) and the type of adjacent GI tract (duodenum/small intestine vs colon) were examined for an impact on the results and conclusions. However, no findings that could affect the results and conclusions were obtained. This point should be further studied in the future work.

By a search using the keywords “spacer, radiation” in PubMed, we found various reports on the use of hydrogel for prostate cancer and the use of Gore-tex® sheets and a tissue expander for abdominal and other pelvic tumors. Hydrogel is gradually absorbed, but Gore-Tex® and a tissue expander are not absorbed and the latter must be removed after radiation therapy. Migration of artificial materials into the small bowel was described in case reports [35, 36]. Ogino et al. reported that migration of the spacer and small bowel obstruction occurred in a patient in whom Gore-tex® was used as the spacer [35]. Thus, complications can occur due to the foreign nature of the spacer. Multiple cases using the omentum as the spacer for proton therapy have been reported [17]. In this study, the greater omentum was inserted as the spacer. However, there has been no discussion about its advantages and disadvantages.

One advantage of a GO spacer is that it might reduce the risk of complications (e.g., migration and infection) because the greater omentum is an in vivo material. One disadvantage of a GO spacer is that it might be difficult to use a GO spacer for cases other than abdomen and pelvic tumors, cases with an operative history of the abdomen and pelvic area, and cases of a large tumor that was difficult to cover all around with a greater omentum spacer. In other words, cases in which a GO spacer can be used are limited. For such cases, an artificial material such as Gore-Tex® or a tissue expander must be used as the spacer, but the risk of complications as described above must be considered.

Recently, research on a bioabsorbable spacer using polyglycolic acid (PGA) has advanced [37]. If a bioabsorbable spacer is put to practical use, there is a possibility of solving the problems that can occur when the greater omentum and artificial materials are used as spacers.

There are some limitations of this study. First, there were patients in whom the tumor shrank after the spacer surgery. The cause was excision of a part of the tumor during the spacer surgery or the use of an anticancer drug. Second, CT slice thickness was not uniform and was not small. We think that the slice thickness of CT should be uniform and small. However, it was not possible to use a uniform thin slice CT because this study was conceived after the patients had been treated. Third, 4D-CT was typically considered for RT with upper abdominal tumors. However, this study was conceived after the patients had been treated. Because RT for patients with upper abdominal tumors was assumed to use respiratory gating, the treatment plans were created assuming that the internal margin was included in the PTV margin. Fourth, we did not examine robust planning in particle therapy. In this study, isotropic margins were used for all treatment modalities to simplify comparison of dose distributions for C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT. Also, the beam angles to hit the tumor after passing through the spacer were not used because the spacer was adjacent to the GI tract. Therefore, we decided not to change the margin with or without spacer. Fifth, we did not impose dose constraints on the liver and kidneys. The aim of this study was to determine the effectiveness of the spacer for the GI tract. When we imposed dose constraints on the liver and kidneys as described in Emami B et al. [1], all five cases for C-ion and proton RT plans met those, however, two cases (cases 3 and 4) of five cases of upper abdominal tumors for photon RT plans (both pre- and post-spacer plans) did not meet dose constraint of the liver. Cases 3 and 4 with large tumor for photon RT plans did not meet dose constraint of the liver, therefore cases with large tumor for photon plans may not meet the dose constraint of the liver with or without the spacer.

Conclusions

The GO spacer shows a significant dose reduction effect on the GI tract for C-ion RT, proton RT and photon RT.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- C-ion:

-

Carbon-ion

- CT:

-

Computed Tomography

- CTV:

-

Clinical target volume

- D2 cc:

-

The most exposed 2 cc volume of the organ

- D2%:

-

Minimum dose to ‘hottest’ 2% of the volume

- D50%:

-

Median dose

- D98%:

-

Minimum dose to ‘hottest’ 98% of the volume

- Dmax:

-

Maximum dose

- Dmean:

-

Mean dose

- DVHs:

-

Dose volume histograms

- EQD2:

-

Equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions

- FDG-PET:

-

Hybrid fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- GO spacer:

-

The greater omentum spacer

- GTV:

-

Gross tumor volume

- HI:

-

Homogeneity index

- HIMAC:

-

Heavy-Ion Medical Accelerator in Chiba

- IMRT:

-

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy

- OARs:

-

Organs at risk

- PTV:

-

Planning target volume

- RBE:

-

Relative biological effectiveness

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- SFUD:

-

Single-field uniform-dose

- SOBP:

-

Spread-out Bragg peak

- TPS:

-

Treatment planning system

- Vx:

-

The volumes at least received x Gy

References

Emami B, Lyman J, Brown A, Coia L, Goitein M, Munzenrider JE, et al. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):109–22.

Igaki H, Mizumoto M, Okumura T, Hasegawa K, Kokudo N, Sakurai H. A systematic review of publications on charged particle therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23(3):423–33.

Tsujii H, Kamada T. A review of update clinical results of carbon ion radiotherapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(8):670–85.

Kamada T, Tsujii H, Blakely EA, Debus J, De Neve W, Durante M, et al. Carbon ion radiotherapy in Japan: an assessment of 20 years of clinical experience. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):e93–e100.

Prada PJ, Fernandez J, Martinez AA, de la Rua A, Gonzalez JM, Fernandez JM, et al. Transperineal injection of hyaluronic acid in anterior perirectal fat to decrease rectal toxicity from radiation delivered with intensity modulated brachytherapy or EBRT for prostate cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69(1):95–102.

Wilder RB, Barme GA, Gilbert RF, Holevas RE, Kobashi LI, Reed RR, et al. Cross-linked hyaluronan gel reduces the acute rectal toxicity of radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;77(3):824–30.

Daar E, King L, Nisbet A, Thorpe RB, Bradley DA. Viscosity changes in hyaluronic acid: irradiation and rheological studies. Appl Radiat Isot. 2010;68(4–5):746–50.

Pinkawa M, Corral NE, Caffaro M, Piroth MD, Holy R, Djukic V, et al. Application of a spacer gel to optimize three-dimensional conformal and intensity modulated radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(3):436–41.

Noyes WR, Hosford CC, Schultz SE. Human collagen injections to reduce rectal dose during radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;82(5):1918–22.

Mariados N, Sylvester J, Shah D, Karsh L, Hudes R, Beyer D, et al. Hydrogel spacer prospective multicenter randomized controlled pivotal trial: Dosimetric and clinical effects of perirectal spacer application in men undergoing prostate image guided intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;92(5):971–7.

Chung H, Polf J, Badiyan S, Biagioli M, Fernandez D, Latifi K, et al. Rectal dose to prostate cancer patients treated with proton therapy with or without rectal spacer. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2017;18(1):32–9.

Susil RC, McNutt TR, DeWeese TL, Song D. Effects of prostate-rectum separation on rectal dose from external beam radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(4):1251–8.

Komatsu S, Hori Y, Fukumoto T, Murakami M, Hishikawa Y, Ku Y. Surgical spacer placement and proton radiotherapy for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(14):1800–3.

Fukumoto T, Komatsu S, Hori Y, Murakami M, Hishikawa Y, Ku Y. Particle beam radiotherapy with a surgical spacer placement for advanced abdominal leiomyosarcoma results in a significant clinical benefit. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(1):97–9.

White JS, Biberdorf D, DiFrancesco LM, Kurien E, Temple W. Use of tissue expanders and pre-operative external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of retroperitoneal sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(2):583–90.

Hoffman JP, Sigurdson ER, Eisenberg BL. Use of saline-filled tissue expanders to protect the small bowel from radiation. Oncology (Williston Park, NY). 1998;12(1):51–4 discussion 4, 60, 2, passim.

Ogino T. Surgical organ displacement: what is the best “materials and methods” for proton radiotherapy? Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25(3):267–8.

Furukawa T, Inaniwa T, Sato S, Shirai T, Takei Y, Takeshita E, et al. Performance of the NIRS fast scanning system for heavy-ion radiotherapy. Med Phys. 2010;37(11):5672–82.

Lomax A. SFUD, IMPT, and plan robustness. In: Rath KA, Sahoo N, editors. editors Part Radiother Emerg Technol treat Cancer. New Delhi: Springer India; 2016. p. 169–94.

Kanai T, Endo M, Minohara S, Miyahara N, Koyama-ito H, Tomura H, et al. Biophysical characteristics of HIMAC clinical irradiation system for heavy-ion radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;44(1):201–10.

Toshito T, Omachi C, Kibe Y, Sugai H, Hayashi K, Shibata H, et al. A proton therapy system in Nagoya proton therapy center. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2016;39(3):645–54.

Paganetti H, Niemierko A, Ancukiewicz M, Gerweck LE, Goitein M, Loeffler JS, et al. Relative biological effectiveness (RBE) values for proton beam therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53(2):407–21.

Fogliata A, Nicolini G, Vanetti E, Clivio A, Cozzi L. Dosimetric validation of the anisotropic analytical algorithm for photon dose calculation: fundamental characterization in water. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(6):1421–38.

Song JH, Son SH, Kay CS, Jang HS. Reducing the probability of radiation-induced hepatic toxicity by changing the treatment modality from helical tomotherapy to fixed-beam intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Oncotarget. 2015;6(32):33952–60.

Hsieh CH, Liu CY, Shueng PW, Chong NS, Chen CJ, Chen MJ, et al. Comparison of coplanar and noncoplanar intensity-modulated radiation therapy and helical tomotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:40.

Kuo YC, Chiu YM, Shih WP, Yu HW, Chen CW, Wong PF, et al. Volumetric intensity-modulated arc (RapidArc) therapy for primary hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison with intensity-modulated radiotherapy and 3-D conformal radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:76.

Ismael HN, Denbo J, Cox S, Crane CH, Das P, Krishnan S, et al. Biologic mesh spacer placement facilitates safe delivery of dose-intense radiation therapy: a novel treatment option for unresectable liver tumors. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(10):1591–6.

Yoon SS, Aloia TA, Haynes AB, Kambadakone A, Kaur H, Vauthey JN, et al. Surgical placement of biologic mesh spacers to displace bowel away from unresectable liver tumors followed by delivery of dose-intense radiation therapy. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2014;4(3):167–73.

Komatsu S, Iwasaki T, Demizu Y, Terashima K, Fujii O, Takebe A, et al. Two-stage treatment with hepatectomy and carbon-ion radiotherapy for multiple hepatic epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8729–35.

Endo S, Takada M, Onizuka Y, Tanaka K, Maeda N, Ishikawa M, et al. Microdosimetric evaluation of secondary particles in a phantom produced by carbon 290 MeV/nucleon ions at HIMAC. J Radiat Res. 2007;48(5):397–406.

Haettner E, Iwase H, Schardt D. Experimental fragmentation studies with 12C therapy beams. Radiat Prot Dosim. 2006;122(1–4):485–7.

Safai S, Bortfeld T, Engelsman M. Comparison between the lateral penumbra of a collimated double-scattered beam and uncollimated scanning beam in proton radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53(6):1729–50.

Tsujii H, Minohara S, Noda K. Heavy-particle radiotherapy: system design and application. Reviews Of Accelerator Science And Technology: Volume 2: Medical Applications of Accelerators: World Scientific; 2009. p. 93–110.

Suit H, DeLaney T, Goldberg S, Paganetti H, Clasie B, Gerweck L, et al. Proton vs carbon ion beams in the definitive radiation treatment of cancer patients. Radiother Oncol. 2010;95(1):3–22.

Ogino T, Sekimoto M, Nishimura J, Takemasa I, Mizushima T, Ikeda M, et al. Intraluminal migration of a spacer with small bowel obstruction: a case report of rare complication. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:30.

Steinhagen E, Khaitov S, Steinhagen RM. Intraluminal migration of mesh following incisional hernia repair. Hernia. 2010;14(6):659–62.

Akasaka H, Sasaki R, Miyawaki D, Mukumoto N, Sulaiman NS, Nagata M, et al. Preclinical evaluation of bioabsorbable polyglycolic acid spacer for particle therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90(5):1177–85.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (16ck0106034h0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception, design, and drafting the manuscript were performed by MY, HS, YI, YM, TK, NY, HA, MH, MI, KN. Data collection and interpreting were performed by TO, TY, YK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yamada, M., Sato, H., Ieko, Y. et al. In silico comparison of the dosimetric impacts of a greater omentum spacer for abdominal and pelvic tumors in carbon-ion, proton and photon radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol 14, 207 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1411-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-019-1411-0