Abstract

Background

In the intricate tapestry of food security, wild food species stand as pillars, nourishing millions in low-income communities, and reflecting the resilience and adaptability of human societies. Their significance extends beyond mere sustenance, intertwining with cultural traditions and local knowledge systems, underscoring the importance of preserving biodiversity and traditional practices for sustainable livelihoods.

Methods

The present study, conducted between February 2022 and August 2023 along the Line of Control in India’s Kashmir Valley, employed a rigorous data collection encompassing semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and specific field observations facilitated through a snowball sampling technique.

Results and discussion

The comprehensive inventory includes 108 edible plant and fungal species from 48 taxonomic families, with Rosaceae (N = 11) standing out. Young and soft leaves (N = 60) are an important component of various culinary preparations, with vegetables (N = 65) being the main use, followed by fruits (N = 19). This use is seasonal, with collection peaks in March–April and June–August (N = 12). The study also highlights the importance of use value (UV), with Portulaca oleracea standing out as the plant taxon (UV = 0.61), while Asyneuma thomsoni has the lowest use value (UV = 0.15). Many species such as Senecio chrysanthemoides, Asperugo procumbens, Asyneuma thomsoni, and Potentilla nepalensis were classified as new for gastronomic use. Furthermore, the study underlines the great cultural importance of mushrooms such as Morchella esculenta and Geopora arenicola in influencing social hierarchies within the community. However, the transmission of traditional knowledge across generations is declining in the region. At the same time, the conservation of endangered plant species on the IUCN Red List, such as Trillium govanianum, Taxus wallichiana, Saussurea costus, and Podophyllum hexandrum, requires immediate attention.

Conclusion

Conservation measures should be prioritized, and proactive remedial action is needed. Further research into the nutritional value of these edible species could pave the way for their commercial cultivation, which would mean potential economic growth for local communities, make an important contribution to food security in the area under study, and contribute to scientific progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wild foods, encompassing plants and fungi that flourish in natural environments without human intervention, constitute a fundamental resource harvested by numerous rural communities globally [1]. The practice of gathering wild foods and incorporating them into daily diets has become widespread, significantly enhancing the nutritional status [2, 3]. This practice serves the dual purpose of reducing reliance on commercial food sources and bolstering food security. The indigenous wisdom underlying these practices is invaluable, highlighting its practical benefits. Wild edible species are crucial in sustaining millions of people, particularly in rural and impoverished regions [4]. The integration of indigenous wisdom and ethno-scientific methods into contemporary conservation and sustainable resource management practices is increasingly vital [5]. Such integration is crucial for constructing resilient and sustainable food systems. This approach aligns with Article 8(j) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which underscores the importance of traditional knowledge (TK) in the development of sustainable food systems in specific regions [5, 6]. Furthermore, biocultural refugia serve as repositories of traditional knowledge, preserving the essence of conventional food systems and historically playing a central role in safeguarding communities during famines [7].

Understanding the age-old practice of traditional plant foraging, deeply embedded in local customs, is essential as it catalyzes the emergence of new gastronomic identities while supporting the sustainability of isolated indigenous food systems [8]. Reviving and examining the biocultural culinary heritage that underpins the development of indigenous gastronomy on a global scale reveals the indispensable role of traditional knowledge (TK). This knowledge offers a wealth of ancient ingredients, forgotten plants, specific collection times for particular species, and cultural significance, which, when harnessed, support the fight against food insecurity [9].

However, significant conservation issues are associated with the harvesting of wild foods. Overharvesting, climate change, and urbanization pose substantial threats to these resources. Unsustainable practices can lead to the depletion of wild species, undermining ecological balance and the availability of these critical food sources for future generations [10, 11]. Indigenous communities are custodians of vanishing botanical knowledge and ancient ecological narratives. The global trend of urbanization is disrupting their way of life, impeding the intergenerational transmission of knowledge, and potentially leading to the erosion of traditional knowledge. [12, 13]. In this regard, the urgency to preserve this reservoir of knowledge is unmistakable and necessitates its careful integration into sustainable food and health paradigms, as strongly advocated by Aziz et al. [14]. Developing a concrete plan to protect this invaluable treasure from the relentless passage of time and the unstoppable force of modernization requires intensive participation in extensive ethnobotanical field studies. As part of our endeavor, the present study aims to document the traditional knowledge of wild food species among the people living in Kashmir. The primary objectives of our scientific inquiry are twofold: firstly, to meticulously document the diverse edible wild food species prevalent among the populace residing along the Line of Control within the Kashmir Valley of India, and secondly, to comprehensively record essential aspects of the primary gastronomic uses, utilized plant parts, temporal patterns of collection, cultural importance, intergenerational dissemination of traditional culinary knowledge, and conservation statuses associated with these documented species.

Materials and methods

Study area

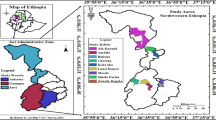

The strategically important Kashmir Valley is located in the northernmost part of India (Fig. 1) and borders China to the northeast, which includes the autonomous Uyghur region of Xinjiang and the autonomous region of Tibet. In the west and northwest, it borders Pakistan, which is demarcated by the Line of Control (LoC) [15]. In addition, the valley is surrounded to the south by other Indian states such as Himachal Pradesh and Punjab.

The region covers an area of around 15,948 square kilometers and has a diverse demography, with Muslims forming the majority (67%) along with Hindus, Sikhs, and Buddhists. Known for its temperate climate and ecological richness, the Kashmir Valley has a mosaic of forest types ranging from the humid temperate zone of the Himalayas to sub-alpine forests. The intricate geopolitical dynamics, cultural heritage, and natural beauty make Kashmir a significant and complex part of the Union Territory. Agriculture is the cornerstone of the Kashmir Valley [16] and is closely associated with various related services. Outside agriculture, the population is engaged in various activities, some in trade, others as day laborers, semi-skilled artisans, and shepherds, all of whom make a unique contribution to the vibrant picture of this land. According to the anthropological survey of India under the People of India project, there are 111 ethnic groups living in erstwhile Jammu and Kashmir [17].

Data collection

The present study was conducted through field interviews that took place from February 2022 to August 2023 in the Kashmir Valley. A total of 97 informants, including 52% female and 48% male participants aged between 20 and 75 years from N = 9 different villages (Table 1), were selected using the snowball method. Data collection included semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, and field observations following the well-established methods of Manzoor et al. [15] and Mir et al. [18]. Key information included edible wild plant species, their local nomenclature, growth habits, parts used, collection times, market value, medicinal properties, and culinary uses (e.g., vegetables or fruits). The questionnaires were filled in Urdu and Kashmiri and facilitated by pictures and plant specimens collected during the survey, which helped in the identification of the specimens. Where necessary, individual interviews were conducted to supplement the responses to the questionnaires. The study strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines of the International Society for Ethnobiology (https://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programmes/ise-ethics-programme/code-of-ethics/), and traditional knowledge was carefully collected from various locations in the Kashmir Valley.

To ensure careful examination and the preparation of herbarium specimens, we worked with knowledgeable informants from each study area. For accurate plant identification, we relied on regional literature sources [15, 19,20,21,22]. In cases where disagreements over local nomenclature arose, group consensus was reached through intense debate. To achieve accurate taxonomic identification, the collected specimens were examined in detail under the invaluable guidance of taxonomists from Jiwaji University, Gwalior, India. Moreover, the correctness of the nomenclature was confirmed by referring to the WFO (2024) to maintain the highest standards of accuracy and scientific rigor.

Socioeconomic background

The people living in the frontier areas of the Kashmir Valley are particularly dependent on the local ecology, especially through the practice of relying on wild foods [15]. The rugged terrain and often inaccessible landscapes have necessitated a harmonious relationship with nature in which these communities have honed their skills in foraging for wild foods. Wild foods, including a variety of indigenous plants and seasonal produce, contribute significantly to the diet of these frontier communities. This reliance on wild foods not only serves to meet their nutritional needs but is also an expression of a deep connection to the land and its biodiversity. The traditional knowledge in Kashmir, which is passed on from generation to generation, gives them the ability to sustain themselves and shows a remarkable balance between adapting to the environment and preserving cultural heritage in their way of life [23, 24]. Figure 2 shows some of the landscapes examined in the study.

Data analysis

The use value (UV) is a metric used in ethnobotany to quantify the significance of a plant species based on the number of different uses reported by informants [25]. This measure helps determine a plant’s versatility or utility, reflecting its cultural and practical importance. The utilization value index (UV) was applied to assess the importance of a species to the informants and its gastronomic use among the edible wild species.

Utilization value was calculated using the following formula:

where Ui is the total number of utilization reports of each informant, and N is the total number of informants involved in the study.

Further, a chord diagram was used to show species distribution across the families, and the same was employed to reveal the part usage and specific food use associated with the documented species. Knowledge of the wild food used by the respondents (selected age groups) across the different selected sites in the study area was also represented via a chord diagram, and we used the statistical software Origin Pro 2021. Neighbor-joining clustering was also performed using the PAST software showing the Jaccard similarity index for the different studies. This comprehensive approach enabled a deeper understanding of the data set, revealing the species being reported for the first time, resulting in exploring the novelty of the present study.

Results and discussion

Diversity of wild edible plants

Wild edible plant species are an important source of food for rural populations worldwide. In the current study, a comprehensive inventory of 99 edible plants and 9 fungi species (sum N = 108) from 48 taxonomic families was documented through informant reports (Table 2). The most important family among these was Rosaceae (N = 11), closely followed by Polygonaceae (N = 9), Asteraceae (N = 7), Lamiaceae (N= 6), Plantaginaceae (N = 5), Amaranthaceae, Apiaceae, and Berberidaceae (N = 3 each) (Fig. 3a). The great importance of Rosaceae, Polygonaceae, and Asteraceae is due to the favorable environmental conditions and the suitability of the habitats in the region. In addition, the local population has extensive ecological and traditional knowledge about these families [26,27,28].

a Chord diagram showing the distribution of species across the families; b chord diagram showing the percentages of the part usage contributed by the corresponding plant species. The complete names of the species are provided in Table 2

Analysis of the results revealed that the most common life form among the documented species was herbs (n = 73), followed by shrubs (n = 13), fungi, trees (n = 9 each), ferns (n= 3), and climbers (N = 1) (Table 2). These results are consistent with previous studies in the western Himalayas [29, 30]. A comprehensive list of cataloged species can be found in Table 2. The use of these documented species within the ethnic group can be attributed to factors such as plant diversity, accessibility, deep-rooted knowledge of edible wild plant species, healthy condition of forest flora, and economic constraints. A variety of plant parts are used in different culinary preparations, with leaves (55%, N = 60), fruits (16%, N = 17), roots (13%, N = 14), and fruiting bodies (8%, N = 9) being the most commonly used ingredients (Fig. 3b). The predominant use of leaves can be attributed to the fact that they are easy to collect and have a rich phytochemistry [31]. In addition, the leaves are frequently consumed as food in the region [32].

Several studies [33,34,35] have documented the consumption of wild foods in the Kashmir Valley. However, this study is pioneering in reporting the use of wild foods by populations residing near the Line of Control between India and Pakistan. Notably, our study also reported some species previously unreported in this region. To verify and confirm these findings, we compared our results with prior studies [29, 36,37,38,39,40,41] using Past 4.03 software to plot the Jaccard similarity index via Neighbor-joining clustering (Fig. 4). This index offers profound insights, recognizing both new and gastronomically similar species. Our results revealed 14 species (Agaricus arvensis, Allium humile, Bergenia ligulata, Campanula latifolia, Cirsium vulgaris, Geranium pratense, Polygonum alpinum, Prunus cerasifera, Pteridium revolutum, Rosa damascene, Rhizopogon villosus, Senecio chrysanthemoides, Sedum ewersii, and Sisymbrium loselli) that had not been previously reported, underscoring the novelty and importance of our study in expanding the understanding of wild food use in the region. Clustering analysis identified three primary clusters (Fig. 4). Cluster I, representing the present study, stands alone, indicating distinct species composition with low similarity and high diversification compared to other studies. This distinctiveness likely results from the unique geographical setting (predominantly mountainous with rich forest cover) and local cultural diversity. Clusters II and III comprise other compared studies, showing varying degrees of similarity, with the cluster farthest from Cluster I being the least similar to the present study.

Gastronomic use

Despite the widespread reliance on cultivated crops in many societies, people still rely on wild food species [42]. Surprisingly, this ancient practice serves as a food source for at least one billion individuals in their diets. These wild edible plants (WEPs), known for their toughness and adaptability, play a crucial role in addressing important challenges [43]. They contribute to reducing poverty, improving food security, diversifying agriculture, generating income, and combating malnutrition [44]. In simple terms, these plant treasures continue to be highly important in shaping our interconnected ecosystems and overall human well-being.

In this study, we documented the primary gastronomic uses of various species, i.e., vegetables, fruit, flavoring agents, and tea (Table 2 and Fig. 5a). Among the recorded species, the highest utilization was observed for vegetables (67%, N = 77), followed by fruits (16%,N = 18), tea (13%, N = 15), flavoring agents (2%, N = 3), and jam (2%, N = 2). The predominant usage of these species as vegetables can be attributed to traditional practices, limited agricultural land, and inadequate irrigation. Gajural and Doni [44] reported the predominance of vegetable usage upon investing in traditional wild food in the eastern Himalayas. A detailed examination of the data revealed a relatively limited multi-usage pattern among the species. Among all vegetable species, a maximum of 62 were identified with a unique single use. In contrast, the rest of the three species (Rhizopogon roseolus, R. villosus, and Solanum nigrum) exhibited dual uses, with Solanum nigrum being consumed both as a vegetable and some fruit, and Rhizopogon roseolus and R. villosus serving as both salad components. Similarly, in the case of tea, 9 taxa (Abies pindrow, Betula utilis, Bergenia ciliata, B. ligulata, Persicaria amplexicaulis, P. nepalensis, Phlomoides bracteosa, Taxus wallichiana, and Thymus linearis) were exclusive to tea consumption. At the same time, 6 species (Morus nigra, M. alba, Impatiens glandulifera, Geranium pratense, Fragaria nubicola, and Geranium wallichianum) were commonly used for both fruit and tea purposes, demonstrating a dual usage pattern. Similarly, Kunwar et al. [45] reported the single and multistage from west Nepal. Meanwhile, among all documented species, no species displayed shared characteristics across all documented gastronomic attributions. To quantify the relationships between species and gastronomic usage, the chord diagram was employed, providing insights into the gastronomic usage for the corresponding species (Fig. 5b).

a Percentage of different gastronomic uses; b Chod diagrams showing the between documented species and their gastronomic use. The complete names of the species are provided in Table 2

The use of herbs as vegetables is widespread throughout the Kashmir Valley. In the present study, we found that women were the primary source of information on the usages of species as vegetables, and most of the women are associated with gastronomic uses, as the kitchen belongs to them culturally in the region and possesses a potential higher knowledge than men. Dad and Khan [46], Pieroni et al. [47]; Singh et al. [35] also reported the knowledge dominance of female folk on gastronomic uses. The main edible parts of the documented species consumed as vegetables include leaves, young fronds, and fruiting bodies (Table 2). Allium victorialis, Amaranthus dubius, Malva neglecta, Oxalis corniculata, Nasturtium officinale, Oxyria digyna, Cichorium intybus, Plantago depressa, P. major, Rumex nepalensis, Taraxacum officinale, Stellaria media, Silene vulgaris are the most commonly used species as vegetables. A variety of species (Mentha longifolia, M. arvensis, and M. aquatica) were also used for making salad which includes specially made dip formally known as chut/chutney. Leaves of these species are grounded with a traditional mortar and pestle added with salt, and paprika. The obtained recipe (chutney) is mostly consumed fresh. This chutney is believed as a potential appetizer also known to treat gastrointestinal disorders if used without paprika. Some fungi species like Rhizopogon villosus, R. roseolus, Morchella esculenta, Geopora arenicola Agaricus campestris, A. arvensis, Pleurotus ostreatus, Sparassis spathulata, and S. crispa are also consumed as vegetables. The usage of fungi is very much praised, even in luxurious weddings the Morchella esculenta is served as an important elite dish.

Tea holds a unique role among the different ethnic communities globally [48]. In the present study, tea is locally as known as Qoda/Cha/Chai, believed to have warming and revitalizing properties. The consumption of tea tends to surge during the winter season. In our inventory, we documented N = 12 plant species used as substitutes for tea. Notably, six species were more frequently employed for this purpose, with only two plant parts, roots and bark, being utilized. These parts are extracted from species such as Abies pindrow and Taxus wallichiana (bark), Bergenia ciliata, Persicaria amplexicaulis, Fragaria nubicola, Geranium pratense, and Thymus linearis (roots). The typical preparation method involves boiling the roots or bark in water for an extended duration, often exceeding half an hour, with the addition of salt. Additionally, to intensify the flavor and strength of the tea, it is customary to boil the same plant parts and let them steep overnight, followed by a second round of boiling the next day.

The most used species as fruits are Berberis lycium, Celtis australis, Rubus caesius, Podophyllum hexandrum, Viburnum grandiflorum, Prunus cerasifera, P. cornuta, Morus nigra. All the said species are consumed as fresh. There are numerous reports of using wild species as fruits across the globe. Ojelel et al. [49] from Uganda, Mahapatra, and Panda [50], from eastern India, and Khan et al. [51] from Pakistan reported the use of wild species as fruits by the local inhabitants.

The roots of Angelica glauca and A. archangelica and seeds of Bunium persicum were recorded to be employed as flavoring agents. These species are especially added to the local cuisine (Wazwan) to enhance the taste. The Wazwan a multi-course meal in Kashmiri cuisine, endemic to the region is nowadays practiced in almost all traditional cultures in the valley. It is thought to have originated in Iran and evolved. Spices are the backbone of the Wazwan, and traditionally culinary practitioners favor wild species over cultivated or processed species. Our findings agree with Aryal et al. [52] and Bhatia et al. [53], who describe wild plants used in Western Himalayan cuisine, in Udhampur and Jammu, respectively.

Collection of wild edible food species

When collecting the listed species, the locals still have a knowledge potential that shows a strong connection to the local flora. Most species (N = 12) were collected from March to April, and the same number of species were collected from June to August, followed by N = 11 species collected from March to May (Fig. 6). It is important to mention that there is a shortage of cultivated vegetables in the region in March and April due to weather conditions, so people use most wild species in these two months compared to the other months of the year. Species collected in the early spring months include Capsella bursa-pastoris, Convolvulus arvensis, Malva neglecta, Nasturtium officinale, Polygonum aviculare, Ranunculus arvensis, Rumex nepalensis, Rumex acetosa, Sonchus arvensis, Veronica persica, Viola odorata, and Urtica dioica. A complete list can be found in Table 2.

Many species such as Pteridium revolutum, Phytolacca acinosa, and Diplazium maximum are suspected of being poisonous, which is why they are carefully boiled and dried before consumption. These species are also dried in the sun to preserve them for later consumption. The use of wild edible plants (WEP) has some outdated features, such as drying for winter, a tradition that is now only practiced in a few countries around the world [54].

Many species are considered to have medicinal value in addition to gastronomic use (Table 2). It is important to note that the preparations used for cooking are also used as medicine, i.e., species that are consumed as food are themselves medicine. Species such as Portulaca oleracea are used as an immune-boosting agent for postpartum weakness. In addition, the species is also recommended by local traditional healers as a remedy for COVID-19, as it is traditionally considered immune-boosting. Similarly, Taraxacum officinale, Cichorium intybus, and Rheum webbianum have been used to promote circulation and for general weakness in new mothers. Fruits of Viburnum grandiflorum are used for bone and joint ailments.

The use value (UV) indicates the importance of a species for the informants and the gastronomic use of the edible wild species. Based on the UVs, the most popular plant species (Fig. 7) among the inhabitants of the study area were Portulaca oleracea (UV = 0.61), followed by Taraxacum officinale (UV = 0.59), Viburnum grandiflorum (UV = 0.58), Cichorium intybus (UV = 0.56) and the lowest use value was reported for Asyneuma thomsoni (UV = 0.15) (Table 2).

The highest use value of Portulaca oleracea is due to the assumption that the species has a potential nutritional value, which is also supported by the scientific evaluation demonstrating the antioxidant potential and the presence of omega-3 fatty acids [55].

Cultural importance and food security

Throughout the region (Kashmir), several of the documented species have been used in local traditions for centuries [56]. Betula utilis, for example, is burnt to produce smoke to ward off evil spirits and is also used by spiritual healers to write scrolls [21]. Similarly, respondents in the present study reported that they keep the part (twig) of Betula utilis in the house to avoid bad luck, Thymus linearis was used to wash dishes due to its fragrance, and petals of Rosa webbiana are dried in the shade and used in tea to enhance aroma and taste. Geopora arenicola and Prunus cornuta are given to the groom to increase vitality and libido. The ink extracted from Ribes orientale is used by local spiritual healers to make amulets. Several documented species, especially various fungi such as Rhizopogon villosus, R. roseolus, Morchella esculenta, and Geopora arenicola (Fig. 8), play a central role in shaping the social hierarchy within the community. These fungi are highly prized, and their consumption is often associated with elite gatherings such as weddings, celebrations, and feasts that symbolize wealth. Morchella esculenta is a prime example of such a species. Other species such as Geopora arenicola and Agaricus compestris also share a similar fate and contribute significantly to social mobility. It is noteworthy that the locals’ belief in the medicinal properties of these wild food species, in addition to their culinary value, serves as a motivating factor for their continued popularity and consumption.

The study area experiences severe winter conditions, particularly between December and February, resulting in food shortages, notably of vegetables, due to heavy snowfall. Consequently, the local population faces inflated prices for available food items, disproportionately affecting those living below the poverty line. However, the region’s abundance of wild food species provides a vital alternative to cultivated crops. Species like Rhizopogon villosus, R. roseolus, Morchella esculenta, Agaricus compestris, and Geopora arenicola are readily accessible in markets, with many individuals selling them from their homes. Additionally, species such as Diplazium maximum, Pteridium revolutum, Geranium wallichianum, Rheum webbianum, and Bergenia ciliata hold economic significance.

The promotion of these wild food plants in the region offers a promising avenue for advancing food sovereignty and ecological sustainability. Embracing the principles of food sovereignty, which advocate for community control over food systems, locals can revive traditional practices associated with wild food species. This includes incorporating these species into local diets to diversify food sources, reduce reliance on conventional agriculture, and market (which is affected by winter), and enhance self-sufficiency and resilience.

Furthermore, the utilization of wild species holds substantial potential for bolstering food security in the region. Practices like “wildlife stewardship,” encompassing traditional land management, seed conservation, and agroforestry systems, can facilitate this endeavor. Policymakers at both state and central levels must enact supportive policies to realize this potential. Additionally, engaging the younger generation through educational initiatives in schools and communities can instill pride in traditional heritage and impart knowledge about the cultural significance of local species. Community events and festivals highlighting the traditional use of these species can further encourage youth participation. Hands-on learning experiences, such as field trips led by local experts, offer direct interaction with the environment and deepen understanding of the cultural importance of local species.

Intergenerational transfer of traditional wisdom

The transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next is crucial for the preservation of cultural heritage, the conservation of biodiversity, and the maintenance of the connection between communities and their local environment [57]. However, our results suggest that traditional knowledge of local wild food resources is no longer passed between generations, as Fig. 9 shows. Our results are in line with [58, 59]. Respondents in our study were selected using the snowball method, where knowledgeable individuals were selected to participate. We found that older individuals were more knowledgeable compared to the younger generation, which they acknowledged. They also gave various reasons for this change. Several factors contribute to the changing knowledge landscape, including cultural changes, urbanization, shifts in family dynamics, and the lure of modern life, technology, and convenience. The media and capitalist influences have also helped to shape the views and behaviors of younger generations. At the same time, modern education is changing people’s attitudes toward modern lifestyles, which in turn is prompting the younger generation to change their lifestyles and move to urban areas, especially the capital city (Srinagar). The studies of Dweba and Mearns [60] and Hanazaki [61] are along the same lines.

To ensure the survival of local plant knowledge, it is important to carry out community programs, cultural initiatives, documentation projects, and research efforts [62]. These initiatives should focus on the preservation of traditional knowledge while considering the changes in culture and society.

Community programs: Engaging local communities in educational programs and workshops can foster a sense of ownership and pride in one’s plant knowledge. These programs can include activities such as plant identification walks, traditional medicine workshops, and gardening initiatives that encourage hands-on learning and participation.

Cultural initiatives Incorporating traditional practices and ceremonies into educational initiatives can help to reinforce the cultural importance of local plant knowledge. This could include events such as seed exchange festivals, storytelling about the importance of plants in local folklore, and celebrations of traditional harvesting rituals.

Documentation projects Documenting local plant knowledge through interviews with community elders, oral traditions, and written records ensures that valuable information is preserved for future generations. This documentation can take various forms, such as written texts, audio recordings, videos, and digital databases so that the information is accessible and can be easily shared.

Research efforts Scientific research into local plants, their uses, and their ecological significance deepens our understanding and appreciation of traditional plant knowledge. Collaborative research projects involving both local communities and academic institutions can provide valuable insights into the medicinal properties, ecological functions, and cultural significance of local flora. While the preservation of traditional knowledge is crucial, it is important to recognize that cultures are dynamic and constantly evolving. Initiatives should be flexible and inclusive, allowing for the incorporation of new perspectives and practices while respecting and honoring traditional forms of knowledge.

Conservation of wild edible food species

In the present study, we found that the conservation of certain plant species such as Trillium govanianum, Taxus wallichiana, Saussurea costus, Podophyllum hexandrum, Dioscorea deltoidea, Bunium persicum, Berberis aristata, Betula utilis, Angelica glauca, and Allium victorialis is of utmost importance given their inclusion in the IUCN Red List (Table 2). Consideration of the conservation needs of these species must take precedence over the implementation of proactive mitigation measures. A prevailing consensus in the current research literature from different regions of the world, reflected in studies such as Jiri et al. [63] and Kang et al. [64], emphasizes sociocultural factors as the predominant drivers of dwindling use of wild edible plant species (WEPs). In the present study, we found that a large majority of respondents (n = 61) discussed the declining availability of edible wild plants (WEPs) in the Anthropocene. This trend is mainly attributed to the continuous exploitation of certain plant species, primarily due to urbanization, traditional medicinal practices, and economic incentives.

In today’s globalized world, road networks play a crucial role in connecting communities and facilitating economic and social interactions. However, the construction of roads has significant negative impacts on natural ecosystems, including physical disturbance and habitat fragmentation. This often leads to biodiversity loss and habitat degradation, as observed in our study and consistent with the findings of Strittholt and Dellasala [65]. In addition, the increased demand for certain plant species (e.g., Podophyllum hexandrum) on the market exacerbates the exploitation of natural resources by local communities for economic reasons [66]. Many plant species are harvested for their traditional medicinal properties. Taxus wallichiana, known as Himalayan yew, for example, is highly sought after for its anticancer properties, leading to excessive harvesting. Trillium govanianum, valued for its traditional medicinal use to treat sexual disorders, is also at risk of being over-harvested for its alleged therapeutic effects. In addition, species such as Dioscorea deltoidea, known for its role in regulating male and female sex hormones, are endangered by unsustainable harvesting practices and pose an imminent threat to their populations and the ecosystems they inhabit. In this context, sustainable management is essential for the conservation of biodiversity and the preservation of ecosystem integrity. Effective strategies include rigorous assessment and monitoring of plant populations (through a combination of field surveys by competent authorities), habitat conservation measures, and enforcement of legislation to prevent overexploitation. In addition, community engagement, educational initiatives, public awareness, and collaboration between stakeholders are crucial to promote responsible harvesting practices and ensure the long-term sustainability of wild plant resources [42].

Conclusions

Considering the prevailing global reliance on cultivated crops, the continued utilization of wild edible species remains indispensable for sustaining the nutritional needs of a substantial portion of the global population, exceeding one billion individuals. These species serve diverse functions encompassing poverty alleviation, bolstering food security, fostering agricultural diversification, generating economic avenues, and ameliorating malnutrition, with far-reaching implications extending to ecological interdependencies. The present investigation delineates the pivotal role of wild food species in the dietary practices of communities inhabiting the border regions of the Kashmir Valley. Constrained by limited agricultural expanses and logistical constraints in transportation, wild food sources assume a fundamental role as dietary staples. Notably, the seasonal collection of species is a prominent practice, with select taxa, such as Morchella esculenta and Geopora arenicola, significantly influencing social hierarchies within local communities. Nevertheless, the continuity of traditional knowledge transmission across successive generations confronts discernible challenges, primarily attributed to the disruptive impacts of urbanization on lifestyle trajectories. Urgent conservation strategies are imperative, particularly for endangered plant species cataloged in the IUCN Red List, exemplified by entities like Trillium govanianum and Taxus wallichiana. Proactive interventions are indispensable to safeguard biodiversity and the associated reservoirs of traditional knowledge. Concurrently, research investigations into the nutritional attributes of wild species stand poised to underpin commercial cultivation endeavors, thus engendering economic prosperity within local spheres and fostering advancements in scientific comprehension. Moreover, the strategic prioritization of conservation initiatives for imperiled species, advocacy for sustainable harvesting methodologies, ethnobiological documentation of Indigenous knowledge systems, and dissemination of awareness among pertinent stakeholders are essential. Educational initiatives and community outreach initiatives emerge as pivotal mechanisms for engendering a paradigm of sustainable utilization and conservation of wild edible flora.

Availability of data and materials

All the required data are provided in the article.

Abbreviations

- TK:

-

Traditional knowledge

- LoC:

-

Line of control

- UV:

-

Utilization value index

- Ui:

-

Total number of utilization reports of each informant

- N:

-

The total number of informants involved in the study

- IUCN:

-

International Union for Conservation of Nature

- LC:

-

Least concern

- VU:

-

Vulnerable

- CR:

-

Critically endangered

- EN:

-

Endangered

- WEPs:

-

Wild edible plants

References

Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y, Hossaert-McKey M. Fig trees and humans: Ficus ecology and mutualisms across cultures. Oxford: Berghahn Books; 2024. p. 32.

Haq SM, Khoja AA, Waheed M, Pieroni A, Siddiqui MH, Bussmann RW. Plant cultural indicators of forest resources from the Himalayan high mountains: implications for improving agricultural resilience, subsistence, and forest restoration. Res Sq. 2024. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3850401/v1.

Jan M, Mir TA, Jan HA, Bussmann RW, Aneaus S. Ethnomedicinal study of plants utilized in pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum healthcare in Kashmir Himalaya. J Herb Med. 2023;42: 100767.

Wessels C, Merow C, Trisos CH. Climate change risk to southern African wild food plants. Reg Environ Chang. 2021;21:29.

Stryamets N, Mattalia G, Pieroni A, Khomyn I, Sõukand R. Dining tables divided by a border: the effect of socio-political scenarios on local ecological knowledge of Romanians living in Ukrainian and Romanian Bukovina. Foods. 2021;10:126.

Convention on Biological Diversity. Report of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity on its thirteenth meeting. CBD/COP/13/25. In: Proceedings of the thirteenth meeting of the conference of the parties to the convention on biological diversity, Cancun, Mexico; 2016. pp. 4–17.

Gordillo G, Jeronimo OM. Food security and sovereignty. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organisation United Nations; 2013.

Heywood VH. Overview of agricultural biodiversity and its contribution to nutrition and health. In: Fanzo J, Hunte D, Birelli T, Mattei F, editors. Diversifying food and diets—using agricultural biodiversity to improve nutrition and health. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2013. p. 67–99.

Khan S, Hussain W, Sulaiman S, Hussain H, Altyar AE, Ashour ML, Pieroni A. Overcoming tribal boundaries: the biocultural heritage of foraging and cooking wild vegetables among four Pathan groups in the Gadoon Valley. NW Pak Biol. 2021;10:537.

Pruse B, Simanova A, Mežaka I, Kalle R, Prakofjewa J, Holsta I, Laizane S, Sõukand R. Active wild food practices among culturally diverse groups in the 21st century across Latgale. Latvia Biol. 2021;10:551.

Jarzebowski S, Bourlakis M, Bezat-Jarzebowska A. Short food supply chains (SFSC) as local and sustainable systems. Sustainability. 2020;12:4715.

Mir TA, Jan M, Khare RK. Ethnomedicinal application of plants in Doodhganga forest range of district Budgam, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Eur J Integrat Med. 2021;46: 101366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eujim.2021.101366.

Mir TA, Jan M, Khare RK. Ethnomedicinal practices and conservation status of medicinal plants in the Bandipora district of Kashmir Himalaya. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2022;28(2):125–42.

Aziz MA, Ullah Z, Al-Fatimi M, De Chiara M, Sõukand R, Pieroni A. On the trail of an ancient middle eastern Ethnobotany: traditional wild food plants gathered by Ormuri speakers in Kaniguram. NW Pak Biol. 2021;10:302.

Manzoor M, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Gillani SW, Shaheen H, Pieroni A, Al-Ghamdi AA, Elshikh MS, Saqib S, Makhkamov T, Khaydarov K. The local medicinal plant knowledge in Kashmir Western Himalaya: a way to foster ecological transition via community-centred health seeking strategies. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2023;19(1):56.

Hassan M, Haq SM, Majeed M, Umair M, Sahito HA, Shirani M, Waheed M, Aziz R, Ahmad R, Bussmann RW, Alataway A. Traditional food and medicine: ethno-traditional usage of fish Fauna across the valley of Kashmir: a western Himalayan region. Diversity. 2022;14:455.

Bhat FA, Mathur PK. Ethnic plurality in Jammu and Kashmir: A sociological analysis. Man India. 2011;91(3–4):577–96.

Mir TA, Jan M, Jan HA, Bussmann RW, Sisto F, Fadlalla IMT. A cross-cultural analysis of medicinal plant utilization among the four ethnic communities in Northern Regions of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Biology. 2022;11(11):1578.

Murthy KA. Pictorial field guide-floral gallery of Himalayan Valley of flowers and adjacent areas. Chennai, India: Sudarshan Graphics Pvt. Ltd.; 2011.

Menon V. Indian mammals: a field guide. Delhi, India: Hachette India; 2014.

Haq SM, Yaqoob U, Calixto ES, Rahman IU, Hashem A, Abd Allah EF, Alakeel MA, Alqarawi AA, Abdalla M, Hassan M, et al. Plant resources utilization among different ethnic groups of Ladakh in Trans-Himalayan Region. Biology. 2021;10:827.

Jan M, Khare RK, Mir TA. Ethnomedicinal appraisal of medicinal plants from family asteraceae used by the ethnic communities of Baramulla. Kashmir Himalaya Ind For. 2021;147(5):475–80.

Kumar A, Kumar S, Komal RN, Singh P. Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability. 2021;13(6):3062.

Jan M, Mir TA, Ganie AH, Khare RK. Ethnomedicinal use of some plant species by Gujjar and Bakerwal community in Gulmarg mountainous region of Kashmir Himalaya. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2021;21(38):1–23.

Phillips O, Gentry AH, Reynel C, Wilki P, Gávez-Durand CB. Quantitative ethnobotany and Amazonian conservation. Conserv Biol. 1994;8:225–48.

Hassan M, Abdullah A, Haq SM, Yaqoob U, Bussmann RW, Waheed M. Cross-ethnic use of ethnoveterinary medicine in the Kashmir Himalaya—a northwestern Himalayan region. Acta Ecol Sin. 2023;43(4):617–27.

Mir AY, Yaqoob U, Hassan M, Bashir F, Zanit SB, Haq SM, Bussmann RW. Ethnopharmacology and phenology of high-altitude medicinal plants in Kashmir, Northern Himalaya. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2021;22:1–5.

Jan M, Mir TA, Khare RK. Traditional use of medicinal plants among the indigenous communities in Baramulla district, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Nord J Bot. 2022;2022:03387.

Mir TA, Jan M, Khare RK, Dhyani S. Ethno-survey of traditional use of plants in Lolab Valley, Kashmir Himalaya. Indian For. 2021;147(3):281–7.

Rana D, Bhatt A, Lal B, Parkash O, Kumar A, Uniyal SK. Use of medicinal plants for treating different ailments by the indigenous people of Churah subdivision of district Chamba, Himachal Pradesh, India. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23:1162–241.

Ahad L, Hassan M, Amjad MS, Mir RA, Vitasović-Kosić I, Bussmann RW, Binish Z. Ethnobotanical insights into medicinal and culinary plant use: the dwindling traditional heritage of the dard ethnic group in the Gurez region of the Kashmir Valley, India. Plants. 2023;12(20):3599.

Oliveira W, Colares LF, Porto RG, Viana BF, Tabarelli M, Lopes AV. Food plants in Brazil: origin, economic value of pollination and pollinator shortage risk. Sci Total Env. 2024;912: 169147.

Haq SM, Hassan M, Bussmann RW, Calixto ES, Rahman IU, Sakhi S, Ijaz F, Hashem A, Al-Arjani AB, Almutairi KF, Abd Allah EF. A cross-cultural analysis of plant resources among five ethnic groups in the Western Himalayan region of Jammu and Kashmir. Biology. 2022;11(4):491.

Aadil A, Andrabi SAH. Wild edible plants and fungi used by locals in Kupwara district of Jammu and Kashmir, India. Pleione. 2021;15(2):179–89.

Singh B, Sultan P, Hassan QP, Gairola S, Bedi YS. Ethnobotany, traditional knowledge, and diversity of wild edible plants and fungi: a case study in the Bandipora district of Kashmir Himalaya, India. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 2016;22(3):247–78.

Devi U, Bagri A, Bajpai AB. Ethno-medicinal plants used by Jadh Bhotiya community of district Uttarakashi, Uttarakhand, India. Ecol Quest. 2024;35(2):1–23.

Dangwal LR, Raj TL. Diversity, informant consensus factor and cultural significance index of wild edible plants in the Jaunpur region, Tehri Garhwal, Uttarakhand. Ecol Quest. 2024;35(2):1–2.

Waheed M, Haq SM, Arshad F, Bussmann RW, Pieroni A, Mahmoud EA, Casini R, Yessoufou K, Elansary HO. Traditional wild food plants gathered by ethnic groups living in semi-arid region of Punjab, Pakistan. Biol. 2023;12(2):269.

Haq SM, Hassan M, Jan HA, Al-Ghamdi AA, Ahmad K, Abbasi AM. Traditions for future cross-national food security—food and foraging practices among different native communities in the Western Himalayas. Biol. 2022;11(3):455.

Abdullah A, Khan SM, Pieroni A, Haq A, Haq ZU, Ahmad Z, Sakhi S, Hashem A, Al-Arjani AB, Alqarawi AA, Abd Allah EF. A comprehensive appraisal of the wild food plants and food system of tribal cultures in the Hindu Kush Mountain Range; a way forward for balancing human nutrition and food security. Sustainability. 2021;13(9):5258.

Aadil A, Andrabi SAH. An approach to the study of traditional medicinal plants used by locals of block Kralpora Kupwara Jammu and Kashmir India. Int J Bot Studies. 2021;6(5):1433–48.

Mina G, Scariot V, Peira G, Lombardi G. Foraging practices and sustainable management of wild food resources in Europe: a systematic review. Land. 2023;12(7):1299.

Mutie FM, Rono PC, Kathambi V, Hu GW, Wang QF. Conservation of wild food plants and their potential for combatting food insecurity in Kenya as exemplified by the drylands of Kitui County. Plants. 2020;12–9(8):1017.

Gajurel PR, Doni T. Diversity of wild edible plants traditionally used by the Galo tribe of Indian Eastern Himalayan state of Arunachal Pradesh. Plant Science Today. 2020;7(4):523–33.

Kunwar RM, Mahat L, Sharma LN, Shrestha KP, Kominee H, Bussmann RW. Underutilized plant species in far west Nepal. J Mount Sci. 2012;9:589–600.

Dad JM, Khan AB. Edible wild plants of pastorals at high-altitude grasslands of Gurez Valley, Kashmir. India Ecol Food Nutr. 2011;50:281–94.

Pieroni A, Vandebroek I, Prakofjewa J, Bussmann RW, Paniagua-Zambrana NY, Maroyi A, Torri L, Zocchi DM, Dam ATK, Khan SM. Taming the pandemic? The importance of homemade plant-based foods and beverages as community responses to COVID-19. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2020;16:75.

Guo K, Zhang N, Zhang J, Zhang M, Zhou M, Zhang Y, Ma G. Cantonese morning tea (Yum Cha): a bite of Cantonese culture. J Ethnic Foods. 2023;10(1):1–6.

Ojelel S, Mucunguzi P, Katuura E, Kakudidi EK, Namaganda M, Kalema J. Wild edible plants used by communities in and around selected forest reserves of Teso-Karamoja region. Uganda J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2019;15:3.

Mahapatra AK, Panda PC. Wild edible fruit diversity and its significance in the livelihood of indigenous tribals: evidence from eastern India. Food Secur. 2012;4:219–34.

Khan MPZ, Ahmad M, Zafar M, Sultana S, Ali MI, Sun H. Ethnomedicinal uses of edible wild fruits (EWFs) in Swat Valley, Northern Pakistan. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;173:191–203.

Aryal KP, Poudel S, Chaudhary RP, Chettri N, Chaudhary P, Ning W, Kotru R. Diversity and use of wild and noncultivated edible plants in the Western Himalaya. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2014;14:10.

Bhatia H, Sharma YP, Manhas RK, Kumar K. Traditionally used wild edible plants of district Udhampur, J&K, India. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14:1–13.

Hussain J, Khan AL, Rehman N, Hamayun M, Shah T, Nisar M, Bano T, Shinwari ZK, Lee I. Proximate and nutrient analysis of selected vegetable species: a case study of Karak region, Pakistan. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:12.

Palaniswamy UR, Mcavoy RJ, Bible BB. Stage of harvesting and polyunsaturated essential fatty acids concentrations of purslane (Portulaca oleraceae) leaves. J Agri Food Chem. 2001;49(7):3490–9493.

Tali BA, Khuroo AA, Ganie AH, Nawchoo IA. Diversity, distribution and traditional uses of medicinal plants in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) state of Indian Himalayas. J Herbal Med. 2019;1: 100280.

Bridgewater P, Rotherham ID. A critical perspective on the concept of biocultural diversity and its emerging role in nature and heritage conservation. People Nat. 2019;1(3):291–304.

Tomasini S, Theilade I. Local knowledge of past and present uses of medicinal plants in Prespa National Park, Albania. Econ Bot. 2019;73(2):217–32.

Jones EO. Indigenous knowledge management practices in subsistence farming: a comprehensive evaluation. Sustain Technol Entrep. 2024;1–3(2): 100058.

Dweba TP, Mearns MA. Conserving indigenous knowledge as the key to the current and future use of traditional vegetables. Int J Inf Manag. 2011;1–31(6):564–71.

Hanazaki N. Local and traditional knowledge systems, resistance, and socioenvironmental justice. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2024;4–20(1):5.

Shukla SK. Conservation of medicinal plants: challenges and opportunities. J Med Bot. 2023;7:5–10.

Jiri O, Mafongoya PL, Musundire R. The use of underutilised crops and animal species in managing climate change risks. Indig Knowl Syst Clim Chang Manag Afr. 2017;115:316.

Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Ye S, Zhang S, Kang J. Wild food plants and wild edible fungi of Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, central China): herbophilia and indifference to fruits and mushrooms. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012;81:405–13.

Strittholt JR, Dellasala DA. Importance of roadless areas in biodiversity conservation in forested ecosystems: case study of the Klamath-Siskiyou ecoregion of the United States. Conserv Bio. 2001;14–15(6):1742–54.

Khoja AA, Andrabi SAH, Mir RA. Traditional medicine in the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases in northern part of 369 Kashmir Himalayas. Ethnobot Res Appl. 2022;23:1–17.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the local people of Kashmir Valley for sharing traditional knowledge and cooperating during the surveys and interviews. The authors are thankful to those who directly or indirectly helped us during the study.

Funding

No external funding resources were available for this particular study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MH contributed to conceptualization; MH and MSA were involved in methodology; TAM and MJ contributed to data collection; MH and MSA were involved in data analysis; MH contributed to initial draft; MSA and MH were involved in supervision; and MU, AP, MSA, IVK, MAA, and RWB contributed to revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present research work is purely based on field surveys instead of human or animal trials. Therefore, ethical approval and consent to participate are not applicable. However, the formal consent regarding data collection and publication was taken verbally from informants. In addition, ethical guidelines of the International Society of Ethnobiology (https://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/) were strictly followed.

Consent for publication

The present paper does not contain any individual data; therefore, this section does not apply to our study.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, M., Mir, T.A., Jan, M. et al. Foraging for the future: traditional culinary uses of wild plants in the Western Himalayas–Kashmir Valley (India). J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 20, 66 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-024-00707-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-024-00707-7