Abstract

Background

Bipolar disorder is one of the most burdensome severe mental disorders, characterized by high levels of personal and social disability. Patients often need an integrated pharmacological and non-pharmacological approach. Lithium is one of the most effective treatments available not only in psychiatry, but in the whole medicine, and its clinical efficacy is superior to that of other mood stabilizers. However, a declining trend on lithium prescriptions has been observed worldwide in the last 20 years, supporting the notion that lithium is a ‘forgotten drug’ and highlighting that the majority of patients with bipolar disorder are missing out the best available pharmacological option.

Based on such premises, a narrative review has been carried out on the most common “misconceptions” and “stereotypes” associated with lithium treatment; we also provide a list of “good reasons” for using lithium in ordinary clinical practice to overcome those false myths.

Main text

A narrative search of the available literature has been performed entering the following keywords: “bipolar disorder”, “lithium”, “myth”, “mythology”, “pharmacological treatment”, and “misunderstanding”. The most common false myths have been critically revised and the following statements have been proposed: (1) Lithium should represent the first choice for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder; (2) lithium treatment is effective in different patients’ groups suffering from bipolar disorder; (3) Drug–drug interaction risk can be easily managed during lithium treatment; (4) The optimal management of lithium treatment includes periodical laboratory tests; (5) Slow-release lithium formulation has advantages compared to immediate release formulation; (6) Lithium treatment has antisuicidal properties; (7) Lithium can be carefully managed during pregnancy.

Conclusions

In recent years, a discrepancy between evidence-based recommendations and clinical practice in using lithium treatment for patients with bipolar disorder has been highlighted.

It is time to disseminate clear and unbiased information on the clinical efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability and easiness to use of lithium treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. It is necessary to reinvigorate the clinical and academic discussion about the efficacy of lithium, to counteract the decreasing prescription trend of one of the most effective drugs available in the whole medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bipolar disorder is one of the most burdensome severe mental disorders, characterized by high levels of personal and social disability [1]. Patients often need an integrated [2,3,4] and personalized [5, 6] pharmacological and non-pharmacological approach [7, 8]. In particular, when an acute depressive, manic or mixed episode occurs, a pharmacological treatment is usually needed; however, the majority of bipolar patients need long-term treatments, to prolong the free interval, to prevent recurrences, to lessen subthreshold symptoms, to improve relational, social, and occupational functioning [6, 9]. Treatment may be complicated by the presence of comorbid physical illnesses, such as cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndromes (i.e., type 2 diabetes and obesity) [10,11,12], and other mental disorders, such as alcohol or substance disorder, anxiety disorders and personality disorders [13,14,15,16,17,18,19].

Several pharmacological treatments are indicated as first-line treatment for the management of patients with bipolar disorder, with lithium being the gold standard due to its established mood-stabilizing properties, its effectiveness in preventing recurrences, and its anti-suicidal effects [20, 21]. Since its introduction more than 70 years ago [22], lithium has been successfully used to treat bipolar disorder, and it is now unanimously considered the first line option for acute and long-term treatment [23, 24]. Lithium is also highly effective in other serious mental disorders characterized by internalizing and externalizing behaviours, due to its anti-impulsivity and anti-suicidality effects.

Lithium is one of the most effective treatments available not only in psychiatry, but in the whole medicine [25], and its clinical efficacy is superior to that of other mood stabilizers. However, a declining trend on lithium prescriptions has been observed worldwide in the last 20 years, supporting the notion that lithium is a ‘forgotten drug’ [26] and highlighting that the majority of BD patients are missing out the best available pharmacological option [27].

This decreasing trend in the use of lithium in clinical practice can be due to several factors, including its narrow therapeutic index, the side-effect/tolerability profile, the need for regular blood checking [28], the preference of many psychiatrists—particularly the less experienced ones—to use other mood stabilizers which are commonly considered more manageable, safer and less toxic [29]. However, this reflects an important incongruity between evidence-based recommendations and psychiatric clinical practice, and is probably due to the presence of several “false myths” about lithium use among physicians [21, 28], patients and their family members. Providing appropriate education might reverse this concerning trend. Thus, efforts in improving training on lithium should represent a priority for postgraduates and residents around the world in the next years [30].

Based on such premises, we carried out a narrative review of the available literature on the most common “misconceptions” and “stereotypes” associated with lithium treatment; for each false myth, we provide a list of “good reasons” for using lithium in ordinary clinical practice.

Methods

The keywords “bipolar disorder”, “lithium”, “myth”, “mythology”, “pharmacological treatment”, and “misunderstanding” were entered in PubMed, ISI Web of Knowledge, Scopus and Medline. Terms and databases were combined using the Boolean search technique, which consists of a logical information retrieval system (two or more terms combined to make searches more restrictive or detailed).

All selected papers were evaluated by two authors (GS and AF); main findings of included papers are summarized in Fig. 1 and in Table 1.

Results from the narrative clinical review

Based on the search strategy, 30 papers were identified; 12 papers were removed because duplicates; 18 full-text papers were fully analyzed, and eight papers were finally included in the review (Fig. 1).

The majority of studies were carried out in the US [31,32,33,34,35,36,37] in the period 1968–2021 and published in peer-reviewed international scientific journals, such as the American Journal of Psychiatry or Bipolar Disorder (Table 1).

The most common false myths, which have been critically revised, are the following: (1) lithium is not the first choice for treating patients with bipolar disorder; (2) lithium should be avoided in adolescents or elderly patients due to its side effects; (3) the risk of drug–drug interactions is one of the most common limitations in lithium treatment; (4) weekly lab tests are required during treatment with lithium; (5) different lithium formulations do not modify its tolerability profile; (6) no drug has antisuicidal effects; (7) lithium should be avoided during pregnancy (Table 2). The following statements, based upon the most recent evidence on lithium treatment, are proposed: (1) lithium should represent the first choice for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder; (2) lithium treatment is effective in different patients’ groups, including young and elderly patients; (3) the risk of drug–drug interaction during lithium treatment can be easily managed; (4) the optimal management of lithium treatment includes periodical laboratory tests; (5) slow-release lithium formulation has advantages compared to immediate release formulation; (6) lithium has an antisuicidal effect; (7) lithium can be carefully managed during pregnancy.

Myth 1: lithium is not the first choice for treating patients with bipolar disorder

Fact 1: lithium should represent the first choice for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder

Lithium plays a relevant role in acute and long-term management of bipolar disorder and must considered as first-line treatment [38]. In fact, lithium increases the duration of free intervals, minimizes the risk of recurrences and improves inter-episodic symptomatology. Nowadays, lithium is still the gold standard in studies evaluating the efficacy of various medications in the long-term treatment of recurrent mood disorders [39].

Available evidence strongly indicates that patients suffering from bipolar disorder should be primarily treated with lithium, using other mood stabilizers as add-on in case of partial response [40]. Moreover, lithium treatment should be started as early as possible, since response rates for mania and for long-term treatments decrease in individuals with more than three episodes [41]. Maintenance treatment with lithium should be started after two hypomanic episodes or even after one severe psychotic, manic or mixed episode [42].

Patients should be educated about the many benefits of a long-term treatment with lithium, in terms of prophylaxis of mood episodes, reduction of suicidal risk, and neuroprotective effects, with a probable reduction of the risk of dementia and a potential protection against cognitive impairment that is a long-term consequence of multiple mood episodes [43].

Myth 2: lithium should be avoided in adolescents or elderly patients due to its side effects

Fact 2: lithium treatment is effective in different patients’ groups, including young and elderly patients

Lithium represents the gold standard for the treatment of adult with bipolar disorder, but its role in treating bipolar disorder in childhood or adolescence is still debated.

Amerio et al. [44] concluded that lithium monotherapy is safe and effective for acute mania and for the prevention of affective episodes in children and adolescents. A recent umbrella review highlighted that lithium is reasonably safe and effective in children and adolescents, with adverse events similar to those observed in adults; however, the authors underlined that available evidence is limited, and further studies are needed [45].

Optimal dosing strategies have been extensively studied in the pediatric literature. In children weighing > 30 kg, due to the shorter half-life elimination and the greater creatinine clearance, the dosing strategy with lithium begins at a dose of 300 mg daily, followed by a 300 mg weekly increase, until it reaches serum lithium levels ranging from 0.8 to 1.2 mmol/l, similar to those of adults [46]. This strategy yielded mean total daily doses of 1500 mg (SD = 400.9 mg) and a mean weight-adjusted total daily dose of 29.1 mg/kg/day.

According to the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study, lithium is prescribed more frequently to adult (37.8%) than to elderly bipolar patients (29.5%) [47]. However, because elderly subjects are often excluded from randomized clinical trials, studies focused on the treatment of bipolar disorder in older age are lacking and the information is mainly based on data derived from mixed age populations [48, 49]. A growing attention is being given to a subset of patients with bipolar disorder, defined “older age bipolar disorder” (OABD), i.e., bipolar patients aged 50 years and over with prevalent cognitive deficits, increased risk of dementia, impaired psychosocial functioning, frequent physical comorbidities, and premature death [50, 51]. In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in elderly patients with bipolar disorder, lithium was more effective than valproate in reducing manic symptoms during a 9 week follow-up and both drugs were similarly well tolerated [52].

Recently, it has been proposed that optimal serum levels of lithium in elderly patients between 60 and 79 years should be 0.4–0.8 mmol/l, while in patients aged 80 or more lithium levels should be between 0.4 and 0.7 mmol/l [53]. In the case of physical comorbidities, polypharmacy, cerebrovascular diseases, parkinsonism and dementia, a serum lithium concentration equal to or lower than 0.5 mmol/l (measured after 12 h) is recommended [54].

A dose reduction of lithium of about 20% is often required in elderly patients compared to younger patients. However, for maintenance monotherapy in OABD lithium is effective and well tolerated and it still represents the preferred choice, if correctly used. However, special caution is required to prevent nephropathy and intoxication.

In the elderly, lithium seems to be used more frequently as add-on to antidepressants in the treatment of resistant depression than in bipolar disorder [55]. Long-term treatment with lithium in the elderly is effective and relatively well tolerated both in patients with bipolar disorder and in those suffering from resistant depression. Morlet et al. [56] found that patients with depressive and bipolar disorder who had taken lithium in previous years (12.5 years on average) had less severe psychiatric symptoms, less severe depressive symptoms, and less use of benzodiazepines compared to those who had not received lithium therapy. Except for hypothyroidism, patients taking lithium have no more side effects compared to those not taking lithium.

Myth 3: the risk of drug–drug interactions represents one of the most common limitations in lithium treatment

Fact 3: drug–drug interaction risk can be easily managed during lithium treatment

Drug–drug interactions with lithium can be pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic in nature.

As regards pharmacokinetic interactions, lithium has a narrow therapeutic index and changes in plasma concentrations can have significant clinical consequences. The ion is extensively absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, is not metabolized and is almost entirely eliminated by the kidneys [57]. Serum lithium levels are sensitive to physiological factors that affect renal function, including age, dehydration, sodium balance; the most important drug interactions occur when co-administered drugs alter renal function, specifically modifying glomerular filtration and tubular reabsorption.

The most commonly prescribed drugs that have the potential to interact with lithium are ACE inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor antagonists (sartans), diuretics, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [58] (Table 3).

Case reports and hospital admission studies have shown that ACE inhibitors and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists can increase lithium serum concentrations, thus increasing the risk of toxicity [59]. Closer monitoring of lithium concentrations is needed when people start either of these drugs, and lithium dose probably needs to be reduced until a stable therapeutic concentration has been achieved. Closer monitoring for several days is also required when those drugs are stopped.

Lithium concentrations must be carefully monitored when a diuretic drug is prescribed. Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics increase sodium reabsorption, which decreases the clearance of lithium and significantly elevates its serum concentrations [60]. Amiloride is recommended as a diuretic because of its mechanism of action that reduces lithium accumulation and improves kidney function in long-term treatment [61].

Patients taking lithium should be advised not to use regularly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that can alter lithium concentrations through multiple mechanisms [62]. If NSAIDs are indicated, they should be used under medical guidance with a close monitoring of lithium concentrations; in these cases, lower lithium doses may be required.

Accelerating lithium elimination can be obtained through decreasing lithium reabsorption in the proximal tubule by osmotic diuresis (e.g., mannitol), carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide, and sodium bicarbonate [63]. Some calcium-channel blockers, such as nifedipine or nimodipine, can increase lithium clearance by producing afferent arteriolar vasodilatation. A similar effect is produced by xanthines, such as aminophylline, theophylline, and caffeine. Abrupt withdrawal from excessive drinking of coffee or tea may decrease lithium clearance, which may result in intoxication [57].

When combining lithium with other mood stabilizers, such as carbamazepine, valproate or lamotrigine, there is no significant influence on the levels of each drug; furthermore, combinations with tricyclic antidepressants are pretty safe [64].

Increased lithium neurotoxicity can be caused by the interaction with many drugs, particularly if they are administered at high doses and in elderly patients. These drugs include first (chlorpromazine and other phenothiazines, haloperidol) and second-generation antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, paliperidone, aripiprazole, and brexpiprazole). Lithium and antidopaminergic drugs can induce a profound dopamine hypofunctionality as a causative mechanism for neurotoxicity, resulting in increased risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, neuroleptic malignant syndrome and tardive dyskinesia [65].

Other interactions include the enhancement and prolongation of the action of competitive (e.g., pancuronium) and depolarizing (succinylcholine) muscle relaxants which, in rare cases, can trigger attacks of congenital muscle fatigue [66].

Patients with bipolar disorder often receive specific medications for treating comorbid physical conditions, such as obesity, hypertension and cardiovascular disorders. Therefore, interactions between lithium and those medications are frequent.

In patients with high blood pressure treated with certain diuretics, i.e., thiazide diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, and angiotensin-II receptor antagonists, or undergoing low sodium diet, serum levels of lithium might increase up to toxic concentrations. Therefore, different therapeutic options, i.e., loop diuretics, should be considered in these patients [67].

Although caution is required when prescribing lithium to subjects with cardiovascular diseases, such as arrythmias and QT prolongation, especially with concomitant electrolyte imbalances [53], Ponzer et al. [51] found a lower risk for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in BD patients receiving lithium.

Since lithium pharmacokinetics and body distribution change with body weight, larger maintenance doses may be required in obese patients. Therefore, a strict monitoring of the onset of potential side effects of lithium [68] is recommended.

According to the most recent recommendations, a target serum lithium concentration range of 0.5–0.8 mmol/L (varying upon clinical indication, age, and concurrent physical status) seems most appropriate for most patients. Lower end levels of the therapeutic range (0.5–0.6 mmol/L) are generally recommended for older patients (50 years and over) and for those taking interacting concomitant medications for other risk factors such as heart disease, renal impairment, diabetes insipidus, thyroid dysfunction [67].

Lithium should be prescribed with caution in patients receiving drugs that can slow its renal elimination and increase the risk of toxic effects (e.g., thiazide diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, NSAIDs, when assumed more than occasionally and for extended periods), and if a low-sodium diet is required for medical reasons [53].

Kuramochi et al. [69] investigated the administration rates of NSAIDs, loop/thiazide diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and/or angiotensin-II receptor blockers between lithium users and age- and sex-matched non-lithium users. They also investigated the number of patients in the two groups with a diagnosis of somatic conditions who were receiving those medications. Results show that prescriptions of the above medications are less frequent in lithium users compared to non-users (18.3 vs. 31.9%), with subsequent suboptimal treatment of medical comorbidities and impact on physical health.

The presence of alcohol use disorders (AUD) and substances use disorders (SUD) should always be considered when initiating a treatment with lithium [70, 71]. Lithium is still considered the first-line treatment in comorbid BD-AUD/SUD patients who show good adherence. Also, medications for AUD can be safely used in BD given the lack of significant pharmacological interactions [72]. However, in these patients the combination of more drugs is often the rule for improving patients’ outcome. For example, in patients affected by bipolar disorder with AUD/SUD, adding an anticonvulsant drug to lithium is preferable to lithium monotherapy for their effects on substance consumption and craving [73]; the combination of lithium and valproate is effective for affective symptoms and reduces substance use, possibly through an indirect effect on mood stability [74]. Nevertheless, studies are still scarce, findings are often inconsistent and with no difference according to the main substance of use [70]. Further studies are needed before evidence-based guidelines can be delivered for clinician's use.

Myth 4: lithium treatment requires weekly lab tests

Fact 4: the optimal management of lithium treatment includes periodical laboratory tests

Lithium treatment can be easily implemented in ordinary clinical practice, both at inpatient and outpatient settings. Before starting treatment with lithium, it is recommended to assess blood concentrations of creatinine and urea-nitrogen (to check renal functioning), the levels of electrolytes (sodium, potassium, calcium), and the levels of thyroid and parathyroid hormones, as well as obtaining an electrocardiogram. Lithium blood concentration should be checked 5 days after the targeted dose is achieved. The evaluation of lithium blood concentration levels can be repeated until lithium reaches its therapeutic levels. Afterwards, lithium, creatinine, and TSH levels should be checked every one to 2 months in the first 6 months, and then every 6–12 months, or as clinically indicated.

The most common early side effects of lithium include reduced urinary concentrating ability (by 15% of normal maximum) with possible polyuria/polydipsia, tremor, and gastrointestinal symptoms. Clinical hypothyroidism and/or increased thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), parathyroid abnormalities (usually normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism), impaired glomerular filtration rate and chronic kidney disease usually occur after a long-term exposure to lithium [75,76,77].

Some of lithium acute side effects can be reduced simply by ensuring that the lowest needed plasma levels are maintained and using prolonged-release formulations that are associated with lower plasma peaks.

In the long term, lithium is associated with a higher risk of impaired glomerular rate filtration and chronic kidney disease stage 3 (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) as compared to valproate, olanzapine and quetiapine (but not CKD stage 4—GFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2); but lithium is significantly less associated with weight gain and hypertension than other mood stabilizers (e.g., valproate, olanzapine and quetiapine) [78]. Long-term antipsychotic exposure, especially some of the most used atypical antipsychotics such as olanzapine or quetiapine, is indeed associated with increased rates of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular diseases, with an excess of mortality due to cardiovascular events [79]. Moreover, long-term exposure to dopamine-blocking agents may have an impact on brain’s reward system and on the extrapyramidal system.

In a small group of patients, lithium is associated with hypercalcemia or normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism (risk of reduced mineral density, osteoporosis and increased fracture risk over the long-term), but their clinical significance remains doubtful. In fact, opposite findings have been found recently, with decreased risk of osteoporosis (HRR, 0.62; 95% CI 0.53–0.72) in bipolar patients treated with lithium compared to those not receiving lithium. Treatment with antipsychotics, valproate, and lamotrigine was not associated with reduced risk of osteoporosis [80]. Concerning clinical hypothyroidism, annual TSH measurements may be sufficient to prevent overt hypothyroidism; in any case, thyroid function abnormalities should not constitute an outright contraindication to lithium treatment, as well as lithium should not be stopped if a responsive patient develops thyroid abnormalities [81, 82].

No studies have been performed to date evaluating the long-term effect of exposure to prolonged-release lithium versus immediate-release lithium on thyroid and renal function; however, one can expect that the lower peak plasma levels and the smaller peak-to-through plasma differences of the prolonged-release formulations are associated with a preserved thyroid and renal function.

Concerning adverse effects associated with lithium treatment, some clarifications need to be made. First, severe adverse renal and endocrine outcomes are very rare (although the absolute risk is higher and significant, the absolute number is low). According to a study in two regions of Sweden with 2.7 million inhabitants [83], renal replacement therapy in patients exposed to lithium occurs in 0.53% as compared to 0.08% in the general population (1.2% in those on lithium for more than 15 years), while a more recent study found that chronic kidney disease occurs in 0.6% of patients (median treatment time 19 months) [84]. Moreover, adverse renal consequences are associated with higher mean plasma levels (greater than 0.60–0.70 mEq/L) [85, 86], indicating that a regular monitoring of plasma levels can minimize or even neutralize the risk. Practical guidelines for prevention and management of renal side effects of lithium therapy advise to use a once-daily dosing schedule, which allow an effective treatment while preventing lithium intoxication [87].

Myth 5: different formulations of lithium do not modify its tolerability profile

Fact 5: slow-release lithium formulation has advantages compared to immediate release formulation

Conventional slow-release (SR) lithium preparations provide a modulated release of the active ingredient, that is obtained for the reduced solubility of the saline compound used (lithium sulphate), or with the inclusion of lithium in a less easily absorbable matrix. In both cases, lithium is absorbed more slowly, and the peak plasma concentration, which is lower than the immediate-release (IR) formulations, occurs within 4–12 h; the pharmacokinetics, therefore, follow a plateau.

The slower increase in serum lithium concentrations and the lower Cmax (maximum concentration of drug detected in the blood) with SR formulations compared to IR lithium formulations translate into a reduced rate or less severity for some lithium-related adverse events, including tremors, upper gastrointestinal cramps, nausea, rash, cognitive obtundation, polyuria; a close relationship between changes in blood lithium levels and frequency and severity of side effects has been recently highlighted. Pompili et al. [88] found that SR lithium salts offer clinical advantages over IR formulations in terms of more stable circulating concentrations of lithium, less adverse impact on renal function, low incidence of adverse neurological effects (including cognitive impairment and tremor), low subjectively unpleasant adverse effects such as fatigue and weight-gain, and greater treatment adherence.

Slow-release formulations reduce the post-absorption peaks of plasma levels, which is beneficial for patients with gastric upset or transient side effects (e.g., tremors) secondary to temporary increases in blood levels.

Long-term treatment with SR lithium is associated with less impairment of the kidney's function to concentrate urine compared with IR lithium. A drug delivery system designed to achieve prolonged therapeutic effects by continuously releasing the medication over an extended time after the administration of a single dose reduces daily peaks in plasma lithium concentrations, thus preserving the functionality of the kidney.

A worsening of lower gastrointestinal disorders (e.g., diarrhea) has been occasionally reported with SR formulations of lithium compared to IR formulations [89].

A single daily administration of lithium can produce benefits compared to repeated daily administrations regarding adherence to therapy and reduction of renal and thyroid side effects. Double administration of lithium during the same day could produce renal impairment and a higher risk of polyuria [90]. A single evening dosage is recommended, allowing greater treatment adherence [38].

The overall decrease in adverse events with SR formulations compared to lithium IR formulations may reduce drug discontinuation, although this factor has not been evaluated in controlled clinical studies [90,91,92,93].

Prolonged-release lithium sulphate represents a therapeutic option of great advantage for the clinician, as it allows for constant plasma concentrations of lithium while minimizing the undesirable effects associated with concentration peaks of standard-release formulations [94]. Furthermore, in the event of an overdose of slow-release preparations, the chances of survival increase [95].

According to Bowden [89], adverse effects of lithium can be resolved by dose reduction, extended-release lithium, or combination therapy.

Barbuti et al. [96] investigated differences between patients receiving IR (lithium carbonate) vs. SR (lithium sulphate) lithium formulations in a prospective naturalistic study. Both lithium formulations significantly improved severity (CGI-BP scale) and functioning (FAST scale). These authors found a similar effect of lithium sulfate and lithium carbonate, but a lower incidence of tremors and gastrointestinal disturbances, as well as higher levels of adherence with lithium sulfate compared to lithium carbonate. Both formulations significantly improved both BD episode severity and functioning comparably to each other.

In a randomized clinical trial investigating the switch from IR to SR lithium formulation in poorly tolerant IR lithium-treated patients, Pelacchi et al. [97] found a significantly higher percentage of patients randomized to lithium sulfate (SR) vs. patients randomized to lithium carbonate (IR) who showed an improvement in tremor after the 1st week of treatment; and a persistence of tremor improvement after 12 weeks of treatment. Furthermore, a higher score for the «convenience» item (e.g., route of administration, dosing frequency) of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM scale) was reported by patients randomized to lithium sulfate vs. those randomized to lithium carbonate.

These benefits have led to a frequent use of the extended-release formulation of lithium in many European countries. Still, maybe due to the minimal publicity of these benefits, relatively less use has occurred in other parts of the world.

Myth 6: no drug has an antisuicidal effect

Fact 6: lithium treatment has antisuicidal properties

Lithium is recommended for the reduction of suicide risk among patients with bipolar disorder [98]. The first evidence of lithium’s antisuicidal properties date back to the seminal studies by Barraclough [99], pointing out that lithium was effective in preventing “recurrent affective illness”. Jamison [100] postulated that lithium would demonstrate its role in preventing suicide in bipolar disorders in the next 10 years. Several studies reported strong evidence of the role of lithium in suicide risk protection among patients suffering from mood disorders. The fatality rate was 8.7 times lower during versus after discontinuing lithium and gradual vs. rapid discontinuation of lithium could limit the risk of suicidal behavior [101].

A significant reduction in suicidal risks (attempts > suicides) with lithium maintenance therapy in unipolar ≥ bipolar II ≥ bipolar I disorder to overall levels close to general population rates was found in people treated with lithium. Patients who did not receive lithium had alarming rates of both suicides and suicide attempts in all types of the above-mentioned mood disorders [102].

Patients suffering from bipolar disorder or any other major affective disorder treated with lithium reported a risk of completed and attempted suicides lower than 80% compared with patients treated with other drugs (risk ratio = 4.91, CI 3.82–6.31; P < 0.0001) [103].

A potentially important new observation is a strong association of lithium treatment with the ratio of attempted to completed suicides, which was proposed as an index of the lethality of suicidal acts. In the available literature, the attempted suicide/completed suicide ratio (A/S) is 2.5 times greater among lithium-treated subjects than in those not treated with lithium, and nearly three times higher among bipolar disorder cases, suggesting a reduction in lethality attributable to lithium treatment with fewer fatalities per attempt.

Lithium can have an independent antisuicidal effect because of suicidal behavior in a selected group of high-risk mood disorder patients. Evidence supports the notion of a significantly decreased rate of suicide attempts compared to pre-lithium figures, not only in patients with excellent treatment outcomes, but also in those with moderate or poor response to lithium prophylaxis [104]. These findings highlight a specific antisuicidal action of lithium on the suicide risk dimension, independent from the clinical mood disorder picture [105]. Cipriani et al. [106] found that lithium effectively prevents suicide, deliberate self-harm, and death from all causes in patients with mood disorders. The anti-suicidal properties of lithium in mood disorders have been more recently confirmed [107, 108].

However, some studies did not find consistent antisuicidal action of lithium salts. For example, a randomized controlled trial did not find differences between lithium and valproate in preventing suicide attempts and suicide events in bipolar disorder patients [109]. Another randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial found that adding lithium to treatment does not reduce the incidence of suicide-related events in veterans with major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder who experienced a recent suicide event. In addition, they observed that adding lithium to existing medication regimens does not prevent a broad range of suicide-related events in patients who were being treated for mood disorders and previously engaged in suicidal behavior [110]. However, such exceptions seem irrelevant when considering that nearly three dozen observational trials have found fewer suicides or attempts in patients treated with lithium than without; that there are similar effects in several randomized clinical trials in which suicidal behaviors were considered adverse events rather than an explicit outcome, and that there is marked, temporary increases in suicidal behavior soon after discontinuing lithium treatment [111].

Furthermore, the use of lithium as a lethal mean for suicide has not received support, as data indicate that mortality from an overdose of lithium is similar to that associated with other psychotropic drugs, or even less, as well as suicidal gestures with lithium are uncommon, or even absent, during long-term lithium treatment [98]. The availability of slow-release formulation may reduce side effects and improve adherence [88, 97].

Lithium has the potential to act trans-diagnostically, given evidence emerging from studies of lithium in drinking water and the rates of suicide risk in selective areas with higher concentrations [112]. Despite the controversy, drinking lithium-rich water may protect general populations from suicide. As hospitalizations are a critical time for mood disorders patients, especially at discharge for the increased suicide risk, it is noteworthy to mention a recent study [113] that demonstrates a marked overall reduction in hospitalization during lithium treatment compared to the year before starting lithium, both for bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

Myth 7: lithium treatment should be avoided during pregnancy

Fact 7: lithium can be carefully managed during pregnancy

The decision to treat mood disorders during the peripartum period should be carefully considered, balancing the risk of prenatal and neonatal exposure to the medication versus the potentially deleterious effects of untreated affective episodes on the maternal and neonatal health. Accumulating evidence shows that the continuation of prophylactic medication with mood stabilizers (particularly lithium) during the perinatal period may prevent affective recurrences.

Lithium should be considered the first-choice treatment for bipolar disorder in the peripartum period, especially in women already treated and stabilized with lithium before pregnancy.

Stevens and colleagues [114] demonstrated that the rates of peripartum mood relapses in bipolar disorder are significantly higher if stabilizing therapy is discontinued before or during pregnancy (68%) compared to its continuation (23%). The recurrence risk is much increased if the cessation of the mood stabilizer is rapid and abrupt (within 14 days): about half of women who suspended suddenly or quickly lithium experienced a mood recurrence within 2 weeks [115]. Instead, the maintenance of therapy with lithium reduces the relative risk of relapse by 66% [114].

The efficacy/safety ratio seems to be in favour of lithium in respect to other mood stabilizers in the prophylactic treatment of pregnant women with bipolar disorder. The use of lithium during pregnancy is very effective in preventing depressive and (hypo)manic episodes and associated with few side effects on fetal and newborn health [116]. During pregnancy, the administration of lithium may be correlated with an increased risk of cardiac malformations (2.1% among lithium-exposed pregnancies vs 1.6% among non-exposed), but the difference is not significant [117]. Especially, lithium exposure may induce the development of Ebstein’s anomaly, affecting 5–7 infants per 1.000 live births (instead of 1 per 20.000 live births in general population) [118]. The risk of developing heart defects is associated with the time of lithium intake (higher in the first-trimester of pregnancy) and dosage exposure (lower if serum lithium levels < 0.64 mEq/L and dosages < 600–900 mg/day) [118, 119]. Lithium exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy seems to be associated with higher rates of spontaneous abortion compared with those in general population; however, the risk of miscarriage appears similar when comparing with lithium-unexposed patients with affective disorders [119].

The administration of lithium treatment does not contraindicate breastfeeding because of the absence of severe adverse events reported in infants exposed through maternal milk [120]. Few studies show rare and transient lithium toxicity (e.g., hypotonia, weight loss in the first week, thyroid and renal parameter alterations) in breastfed infants, which recovers after discontinuation of lactation [121]. Lithium salts can be taken during breastfeeding, but a frequent evaluation of infant serum levels and a strict paediatric monitoring are mandatory [122]. However, the decision to breastfeed should also be evaluated in relation to the risk of affective relapses correlated to sleep dysregulation [123].

Some caution must be used in the stabilizing treatment of pregnant women. Preferentially, lithium should be prescribed as monotherapy, in fractionated doses or in slow-release formulations, to avoid plasma peak concentrations and within the lowest therapeutic range throughout pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester. Furthermore, lithium dosages can be reduced immediately before delivery to reduce the risk of postnatal adaptation syndrome [124]. Because of changes in the mother's plasma volume and renal clearance through pregnancy, a close monitoring of lithium blood levels is recommended: lithium blood levels decrease in the first trimester, remains stable in the second trimester, increase in the third trimester and are still slightly increased after delivery [125]. In addition, supplementation with folic acid (5 mg/day) in pregnancy reduces the risk of foetal and neonatal negative outcomes [122].

Discussion

Personalized and integrated treatment, including pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, should be used in patients with bipolar disorder. Although several pharmacological treatments are indicated as first-line treatment for the management of patients with bipolar disorder, lithium is the gold standard due to its established mood-stabilizing properties [23, 24, 126].

Lithium is one of the most effective treatments available in psychiatry [25], and psychiatrists should be aware of the great applicability of lithium use, considering its efficacy and good tolerability profile. However, the recent years have witnessed a decreasing trend in the use of lithium in clinical practice. Many early career psychiatrists or recently graduated physicians do not feel skilled enough to use lithium, which is considered a difficult-to-use agent, mainly for its subtleties, the need for periodical blood checking, and its side effects [29]. Moreover, several stereotypes related to the difficulties in managing lithium treatment exist, which further reduce the use of lithium in clinical practice. Thus, in this narrative review we aim to overcome some of these misconceptions regarding lithium, by counterarguing myths with facts.

Lithium is an excellent treatment for patients suffering from bipolar disorder. In particular, lithium is a valid treatment option in the different phases of bipolar disorder, including treatment of current manic/hypomanic episodes, especially in combination with second-generation antipsychotics. A recent review of all clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder highlights that lithium is recognized as a key pharmacotherapeutic agent in the treatment of bipolar disorder [127].

Lithium has also been found to have an outstanding efficacy in the maintenance or prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder [128, 129], representing the gold standard treatment for the long-term prevention of affective relapses in patients with bipolar disorder [130]. In both controlled clinical trials and in observational studies, lithium has shown its efficacy and superiority in the prophylaxis of any type of affective episode [39, 131,132,133,134,135].

One important misconception regarding lithium is that it should be avoided in adolescents or elderly patients due to its side effects. This notion has been counteracted by several clinical studies, which have highlighted that lithium is well-tolerated and effective both in adolescents and in elderly patients with bipolar disorder [46, 136]. In particular, the recent umbrella review by Janiri et al. [45] found that lithium is superior to placebo in pediatric and adolescent patients with bipolar disorder. All studies specified that lithium was generally well tolerated in this group of patients, with common side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal, polyuria or headache) similar to those reported in adults. As regards the use of lithium treatment in elderly patients with bipolar disorder, De Fazio et al. [136] found that lithium was superior to placebo and to other mood stabilizers in treating mania. The efficacy of lithium in geriatric patients with resistant major depressive disorder is supported also by Ross [137] and by Cooper et al. [138]. Regarding lithium tolerability in elderly patients, the clear evidence is that lithium may be relatively well-tolerated, but low doses should be used in the elderly, since the risk of adverse events increases according to a dose-dependent pattern.

Many early career psychiatrists frequently report to not prescribe lithium treatment since they feel not enough skilled in detecting and managing the potential drug–drug interactions and their impact on patients. This misconception highlights the need for an adequate training of prescribers on the potential pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic interactions of lithium. Improving knowledge and confidence with lithium monitoring can significantly contribute to improve patient outcomes and increase lithium use in ordinary clinical practice. The risk of potential drug–drug interactions can be easily monitored in patients treated with lithium, also considering that the risk increases when patient gets older because of declining renal function and accumulation of medical comorbidities [139]. Other conditions requiring a careful evaluation of lithium treatment are those causing haemodynamic and volume alterations such as dehydration, fever, gastrointestinal loss, perioperative management and surgery. Prescribers should be aware that the most common (potential) interactions occur with ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists (sartans), diuretics, and NSAIDs. Combinations of these drugs are frequent, so clinicians—being aware of their additive effects—should regularly check lithium concentration, not excluding lithium treatment. As suggested by Malhi et al. [140], “lithiumeter”, which is a visual and practical guide for determining lithium levels in the management of bipolar disorder, is a useful tool for supporting the use of lithium treatment in ordinary clinical practice. Furthermore, providing patients with correct information on the benefits of lithium treatment is essential to improve their adherence to the prescribed therapy [141,142,143].

Another common stereotype is that using different lithium formulations does not modify lithium tolerability. On the contrary, the availability of prolonged-release lithium formulation represents an important strength of lithium treatment choice since it reduces some of the most common side effects of lithium, such as tremor and gastrointestinal symptoms, and also has a positive effect on adherence [96, 97].

A relevant statement clearly emerging by our review is that lithium has antisuicidal properties, which might be unrelated to its mood-stabilizing effects, considering that suicidality is a complex phenomenon, with multifactorial causes [144,145,146,147,148]. In fact, there is a significant reduction in the number of suicide attempts among individuals who take lithium, even among those who do not respond well to the prophylaxis of mood symptoms with lithium. The anti-suicidal properties of lithium appear to be as effective at low concentrations as at therapeutic levels. Sustained low doses of lithium intake have shown to decrease suicidality. Suicide prevention in patients taking lithium occurs when the serum concentrations are within a therapeutic range of 0.5–1.0 mmol/L. The lowest efficacious lithium level in the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar disorder has been shown to be 0.4 mmol/L, with optimal response achieved at concentrations between 0.6 and 0.75 mmol/L. Those with manic symptoms might benefit from higher levels of lithium concentration. The duration of lithium treatment is also important for suicide prevention. Even among patients with only poor-to-moderate clinical response, a decrease in the number of suicide attempts has been observed when patients take lithium compared to those who do not take it. Research supports the recommendation that lithium treatment should be considered for anyone at high risk for suicide, even if mood-stabilization is not achieved [149, 150].

Finally, a very controversial issue is the use of lithium in pregnancy. The review by Poels et al. [151] reported lower risk estimates of the association between first trimester lithium exposure and risk of congenital malformations than previously reported. Moreover, no association between lithium use and pregnancy or delivery-related outcomes were found, although studies are needed. Therefore, lithium is effective and relatively safe in pregnancy and postpartum for the prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder; during the first trimester, tapering of lithium treatment should be considered weighing benefits against relapse risks. Accumulating evidence shows that the continuation of prophylactic medication with mood stabilizers (particularly lithium) during the perinatal period may prevent affective recurrences. In particular, Stevens et al. [114] demonstrated that the rates of peripartum mood relapses in bipolar disorder are significantly higher if stabilizing therapy is discontinued before or during pregnancy. When lithium is prescribed during pregnancy, some caution must be used, and lithium blood levels should be monitored more frequently, preferably weekly in the third trimester.

Finally, given its neuroprotective and neurotrophic properties, lithium improves cognition, either associated or not to an acute affective episode [152, 153]. Increasing evidence indicates lithium efficacy in neuroprotection, since it restores both neurotransmission and brain structure [154]. The recognition of lithium as neuroprotective agent is explained by the discoveries of several key cell signaling-related enzymes activated by lithium treatment. These include glycogen synthase kinase-3, inositol monophosphatase, phosphoadenosylphosphate phosphatase, and Akt/beta-arrestin 2. Processes associated with these enzymes include autophagy, BDNF cellular signaling, neuroinflammation, mitochondrial function, and apoptosis. The involvement of these processes in a variety of brain disorders beyond bipolar disorders, such as stroke, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, fragile X syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and multiple sclerosis raised the interest in exploring lithium’s potential neuroprotective property in these neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental disorders [155].

The present study has some limitations which must be acknowledged. Firstly, the consensus paper is based on a narrative review of the available literature on efficacy, tolerability and use of lithium in ordinary clinical practice. The search has not adopted a rigorous methodology, analyzing all available databases and sources of information. Moreover, a specific focus on myths/facts related to lithium treatment with a specific focus on adolescent/young patients is missing, since other recent papers have already assessed the use of lithium in such target group.

Conclusions

In recent years, a discrepancy between evidence-based recommendations and clinical practice in using lithium treatment for patients with bipolar disorder has been highlighted.

It is time to disseminate clear and unbiased information on the clinical efficacy, effectiveness, tolerability and easiness to use of lithium treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. The availability of different formulations of lithium represents a further strength of this therapeutic choice, since the treatment can be more easily adapted to patients’ needs.

It is necessary to reinvigorate the clinical and academic discussion about the efficacy of lithium, to counteract the decreasing prescription trend one of the most effective drugs available in the whole medicine.

Availability of data and materials

Upon request to corresponding author.

References

McIntyre RS, Alda M, Baldessarini RJ, Bauer M, Berk M, Correll CU, et al. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with bipolar disorder aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(3):364–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20997.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Bond DJ, Frey BN, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12609.

Kendler KS. Incremental advances in psychiatric molecular genetics and nosology. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(3):415–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20999.

Krueger RF. Incremental integration of nosological innovations is improving psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(3):416–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.21001.

Perugi G, De Rossi P, Fagiolini A, Girardi P, Maina G, Sani G, et al. Personalized and precision medicine as informants for treatment management of bipolar disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;34(4):189–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000260.

Linden M. Twelve rather than three waves of cognitive behavior therapy allow a personalized treatment. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):316–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20985.

Flückiger C, Paul J, Hilpert P, Vîslă A, Gómez Penedo JM, Probst GH, et al. Estimating the reproducibility of psychotherapy effects in mood and anxiety disorders: the possible utility of multicenter trials. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):445–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20901.

Leichsenring F, Steinert C, Rabung S, Ioannidis JPA. The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: an umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):133–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20941.

Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377.

Bai YM, Li CT, Tsai SJ, Tu PC, Chen MH, Su TP. Metabolic syndrome and adverse clinical outcomes in patients with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):448. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1143-8.

Kim H, Turiano NA, Forbes MK, Kotov R, Krueger RF, Eaton NR, et al. Internalizing psychopathology and all-cause mortality: a comparison of transdiagnostic vs. diagnosis-based risk prediction. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):276–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20859.

Warner A, Holland C, Lobban F, Tyler E, Harvey D, Newens C, et al. Physical health comorbidities in older adults with bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;326:232–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.083.

Price AL, Marzani-Nissen GR. Bipolar disorders: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2012;85(5):483–93.

Forte A, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Vázquez GH, Pompili M, Girardi P. Long-term morbidity in bipolar-I, bipolar-II, and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:71–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.011.

Arango C, Dragioti E, Solmi M, Cortese S, Domschke K, Murray RM, et al. Risk and protective factors for mental disorders beyond genetics: an evidence-based atlas. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):417–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20894.

Mulder R. The evolving nosology of personality disorder and its clinical utility. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(3):361–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20915.

Correll CU, Solmi M, Croatto G, Schneider LK, Rohani-Montez SC, Fairley L, et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(2):248–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20994.

Klingberg T, Judd N, Sauce B. Assessing the impact of environmental factors on the adolescent brain: the importance of regional analyses and genetic controls. World Psychiatry. 2022;21(1):146–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20934.

Sengupta G, Jena S. Psychiatric comorbidity and quality of life in patients with bipolar disorder. Ind Psychiatry J. 2022;31(2):318–24. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_24_21.

Sampogna G, Janiri D, Albert U, Caraci F, Martinotti G, Serafini G, et al. Why lithium should be used in patients with bipolar disorder? A scoping review and an expert opinion paper. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22(11–12):923–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737175.2022.2161895.

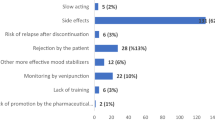

Hidalgo-Mazzei D, Mantingh T, Pérez de Mendiola X, Samalin L, Undurraga J, Strejilevich S, et al. Clinicians’ preferences and attitudes towards the use of lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorders around the world: a survey from the ISBD lithium task force. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2023;11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00301-y.

Cade JF. Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement. Med J Aust. 1949;2(10):349–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.06241.x.

Malhi GS, Tanious M, Das P, Berk M. The science and practice of lithium therapy. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(3):192–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412437346.

Geddes JR, Miklowitz DJ. Treatment of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381(9878):1672–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60857-0.

Leucht S, Hierl S, Kissling W, Dold M, Davis JM. Putting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: review of meta-analyses. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;200(2):97–106. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096594.

Maj M. Lithium, the forgotten drug. In: McDonald C, Schulze K, Murray R, Wright P, editors. Bipolar Disorder. The Upswing in Research and Treatment. 1st Edition- London: CRC Press; 2005

Poranen J, Koistinaho A, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J, Taipale H, Lähteenvuo M. Twenty-year medication use trends in first-episode bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2022;146(6):583–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13504.

Malhi GS, Bell E, Jadidi M, Gitlin M, Bauer M. Countering the declining use of lithium therapy: a call to arms. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2023;11(1):30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00310-x.

Rhee TG, Olfson M, Nierenberg AA, Wilkinson ST. 20-Year trends in the pharmacologic treatment of bipolar disorder by psychiatrists in outpatient care settings. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(8):706–15. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.19091000.

Bartoli F. The lithium paradox: declining prescription of the gold standard treatment for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2023;147(3):314–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13525.

Malhi GS, Bell E, Hamilton A, Morris G, Gitlin M. Lithium mythology. Bipolar Disord. 2021;23(1):7–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.13043.

Fawcett J. Some provocative thoughts about continuation and maintenance treatment. Psychiatr Ann. 2013;24(6):279–80.

Schou M. Lithium prophylaxis: myths and realities. Focus. 2003;1(1):53–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/foc.1.1.53.

Sachs GS, Lafer B, Truman CJ, Noeth M, Thibault AB. Lithium monotherapy: miracle, myth and misunderstanding. Psychiatr Ann. 1994;24(6):299–306. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-19940601-09.

Schou M. Lithium prophylaxis: myths and realities. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(5):573–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.146.5.573.

Shepherd M. A prophylactic myth. Int J Psychiatry. 1989;9:423–5.

Blackwell B, Shepherd M. Prophylactic lithium: another therapeutic myth? An examination of the evidence to date. Lancet. 1968;1(7549):968–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(68)90917-3.

Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, Aronson JK, Barnes T, Cipriani A, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British association for psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(6):495–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881116636545.

Miura T, Noma H, Furukawa TA, Mitsuyasu H, Tanaka S, Stockton S, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of pharmacological treatments in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):351–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70314-1.

Fountoulakis KN, Tohen M, Zarate CA Jr. Lithium treatment of bipolar disorder in adults: a systematic review of randomized trials and meta-analyses. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;54:100–15.

Berk M, Brnabic A, Dodd S, Kelin K, Tohen M, Malhi GS, et al. Does stage of illness impact treatment response in bipolar disorder? Empirical treatment data and their implication for the staging model and early intervention. Bipolar Disord. 2011;13(1):87–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2011.00889.x.

Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, Schaffer A, Beaulieu S, Alda M, et al. Canadian network for mood and anxiety treatments (CANMAT) and international society for bipolar disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(1):1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12025.

Kessing LV, Forman JL, Andersen PK. Does lithium protect against dementia? Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(1):87–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00788.x.

Amerio A, Ossola P, Scagnelli F, Odone A, Allinovi M, Cavalli A, et al. Safety and efficacy of lithium in children and adolescents: a systematic review in bipolar illness. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;54:85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.012.

Janiri D, Sampogna G, Albert U, Caraci F, Martinotti G, Serafini G, et al. Lithium use in childhood and adolescence, peripartum, and old age: an umbrella review. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2023;11(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-023-00287-7.

Findling RL, Kafantaris V, Pavuluri M, McNamara NK, McClellan J, Frazier JA, et al. Dosing strategies for lithium monotherapy in children and adolescents with bipolar I disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(3):195–205. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2010.0084.

Al Jurdi RK, Marangell LB, Petersen NJ, Martinez M, Gyulai L, Sajatovic M. Prescription patterns of psychotropic medications in elderly compared with younger participants who achieved a “recovered” status in the systematic treatment enhancement program for bipolar disorder. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;16(11):922–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e318187135f.

Depp CA, Jeste DV. Bipolar disorder in older adults: a critical review. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):343–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00139.x.

Ljubic N, Ueberberg B, Grunze H, Assion HJ. Treatment of bipolar disorders in older adults: a review. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12991-021-00367-x. (PMID: 34548077; PMCID: PMC8456640).

Beunders AJM, Orhan M, Dols A. Older age bipolar disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2023;36(5):397–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000883.

Ponzer K, Millischer V, Schalling M, Gissler M, Lavebratt C, Backlund L. Lithium and risk of cardiovascular disease, dementia and venous thromboembolism. Bipolar Disord. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.13300.

Young RC, Mulsant BH, Sajatovic M, Gildengers AG, Gyulai L, Al Jurdi RK, et al. GERI-BD: a randomized double-blind controlled trial of lithium and divalproex in the treatment of mania in older patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(11):1086–93. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.15050657.

Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, Bergink V, Grof P, Hajek T, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2.

Shulman KI, Almeida OP, Herrmann N, Schaffer A, Strejilevich SA, Paternoster C, et al. Delphi survey of maintenance lithium treatment in older adults with bipolar disorder: an ISBD task force report. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(2):117–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12714.

Paton C, Barnes TR, Shingleton-Smith A, McAllister-Williams RH, Kirkbride J, Jones PB, et al. Lithium in bipolar and other affective disorders: prescribing practice in the UK. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24(12):1739–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881110367728.

Morlet E, Costemale-Lacoste JF, Poulet E, McMahon K, Hoertel N, Limosin F, et al. Psychiatric and physical outcomes of long-term use of lithium in older adults with bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional multicenter study. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:210–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.056.

Finley PR. Drug interactions with lithium: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2016;55(8):925–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0370-y.

Scherf-Clavel M, Treiber S, Deckert J, Unterecker S, Hommers L. Drug-drug interactions between lithium and cardiovascular as well as anti-inflammatory drugs. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2020;53(5):229–34. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1157-9433.

Hommers L, Fischer M, Reif-Leonhard C, Pfuhlmann B, Deckert J, Unterecker S. The combination of lithium and ACE inhibitors: hazardous, critical, possible? Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39(5):485–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40261-019-00768-7.

Ferensztajn-Rochowiak E, Rybakowski JK. Long-term lithium therapy: side effects and interactions. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16010074.

Kortenoeven ML, Li Y, Shaw S, Gaeggeler HP, Rossier BC, Wetzels JF, et al. Amiloride blocks lithium entry through the sodium channel thereby attenuating the resultant nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Kidney Int. 2009;76(1):44–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.91.

Nunes RP. Lithium interactions with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and diuretics–a review. Arch Clin Psychiatry. 2018;45:38–40.

Schou M, Kampf D. Lithium and the kidneys. In: Bauer M, Grof P, Müller-Oerlinghausen B, editors. Lithium in neuropsychiatry. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis; 2006.

de Montigny C, Cournoyer G, Morissette R, Langlois R, Caillé G. Lithium carbonate addition in tricyclic antidepressant-resistant unipolar depression. Correlations with the neurobiologic actions of tricyclic antidepressant drugs and lithium ion on the serotonin system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(12):1327–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790110069012.

Boeker H, Seidl A, Schopper C. Neurotoxicitiy related to combined treatment with lithium, antidepressants and atpyical neuroleptics: a series of cases. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 2022;162(2):72–6.

Hill GE, Wong KC, Hodges MR. Lithium carbonate and neuromuscular blocking agents. Anesthesiology. 1977;46(2):122–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-197702000-00008.

Wijeratne C, Draper B. Reformulation of current recommendations for target serum lithium concentration according to clinical indication, age and physical comorbidity. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(12):1026–32. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.610296.

Kemp DE, Gao K, Chan PK, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL, Calabrese JR. Medical comorbidity in bipolar disorder: relationship between illnesses of the endocrine/metabolic system and treatment outcome. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(4):404–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00823.x.

Kuramochi S, Yatomi T, Uchida T, Takeuchi H, Mimura M, Uchida H. Drug combinations for mood disorders and physical comorbidities that need attention: a cross-sectional national database survey. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2022;55(3):157–62. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1744-6582.

Kitanaka N, Hall FS, Uhl GR, Kitanaka J. Lithium pharmacology and a potential role of lithium on methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr Drug Res Rev. 2019;11(2):85–91. https://doi.org/10.2174/2589977511666190620141824.

Preuss UW, Schaefer M, Born C, Grunze H. Bipolar disorder and comorbid use of illicit substances. Medicina. 2021;57(11):1256. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57111256.

Grunze H, Soyka M. The pharmacotherapeutic management of comorbid bipolar disorder and alcohol use disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2022;23(10):1181–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2022.2083500.

Janiri D, Di Nicola M, Martinotti G, Janiri L. Who’s the leader, mania or depression? predominant polarity and alcohol/polysubstance use in bipolar disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2017;15(3):409–16. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X14666160607101400.

Coles AS, Sasiadek J, George TP. Pharmacotherapies for co-occurring substance use and bipolar disorders: a systematic review. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(7):595–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12794.

McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, Stockton S, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61516-X.

Albert U, De Cori D, Aguglia A, Barbaro F, Lanfranco F, Bogetto F, et al. Lithium-associated hyperparathyroidism and hypercalcaemia: a case-control cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(2):786–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.046.

Albert U, De Cori D, Aguglia A, Barbaro F, Lanfranco F, Bogetto F, et al. Effects of maintenance lithium treatment on serum parathyroid hormone and calcium levels: a retrospective longitudinal naturalistic study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1785–91. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S86103.

Hayes JF, Marston L, Walters K, Geddes JR, King M, Osborn DP. Adverse renal, endocrine, hepatic, and metabolic events during maintenance mood stabilizer treatment for bipolar disorder: a population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002058. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002058.

Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, De Hert M, Wampers M, Ward PB, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20252.

Köhler-Forsberg O, Rohde C, Nierenberg AA, Østergaard SD. Association of lithium treatment with the risk of osteoporosis in patients with bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiat. 2022;79(5):454–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.0337.

Bocchetta A, Loviselli A. Lithium treatment and thyroid abnormalities. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-0179-2-23.

Haissaguerre M, Vantyghem MC. What an endocrinologist should know for patients receiving lithium therapy. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2022;83(4):219–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ando.2022.01.001.

Bendz H, Schön S, Attman PO, Aurell M. Renal failure occurs in chronic lithium treatment but is uncommon. Kidney Int. 2010;77(3):219–24. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2009.433.

Wiuff AC, Rohde C, Jensen BD, Nierenberg AA, Østergaard SD, Köhler-Forsberg O. Association between lithium treatment and renal, thyroid and parathyroid function: a cohort study of 6659 patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.13356.

Shine B, McKnight RF, Leaver L, Geddes JR. Long-term effects of lithium on renal, thyroid, and parathyroid function: a retrospective analysis of laboratory data. Lancet. 2015;386(9992):461–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61842-0.

Rej S, Herrmann N, Gruneir A, McArthur E, Jeyakumar N, Muanda FT, et al. Association of lithium use and a higher serum concentration of lithium with the risk of declining renal function in older adults: a population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):1913045. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.19m13045.

Schoot TS, Molmans THJ, Grootens KP, Kerckhoffs APM. Systematic review and practical guideline for the prevention and management of the renal side effects of lithium therapy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2019.11.006.

Pompili M, Magistri C, Mellini C, Sarli G, Baldessarini RJ. Comparison of immediate and sustained release formulations of lithium salts. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2022;34(7–8):753–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2022.2122706.

Bowden CL. Key treatment studies of lithium in manic-depressive illness: efficacy and side effects. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(6):13–9.

Carter L, Zolezzi M, Lewczyk A. An updated review of the optimal lithium dosage regimen for renal protection. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(10):595–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305801009.

Durbano F, Mencacci C, Dorigo D, Riva M, Buffa G. The long-term efficacy and tolerability of carbolithium once a day: an interim analysis at 6 months. Clin Ter. 2002;153(3):161–6.

Girardi P, Brugnoli R, Manfredi G, Sani G. Lithium in bipolar disorder: optimizing therapy using prolonged-release formulations. Drugs R D. 2016;16(4):293–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-016-0139-7.

Wallin L, Alling C. Effect of sustained-release lithium tablets on renal function. Br Med J. 1979;2(6201):1332. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.6201.1332.

Cooper TB, Simpson GM, Lee JH, Bergner PE. Evaluation of a slow-release lithium carbonate formulation. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(8):917–22. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.135.8.917.

Grof P. Some practical aspects of lithium treatment: blood levels, dosage prediction, and slow-release preparations. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(8):891–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780080065015.

Barbuti M, Colombini P, Ricciardulli S, Amadori S, Gemmellaro T, De Dominicis F, et al. Treatment adherence and tolerability of immediate- and prolonged-release lithium formulations in a sample of bipolar patients: a prospective naturalistic study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2021;36(5):230–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/YIC.0000000000000373.

Pelacchi F, Dell’Osso L, Bondi E, Amore M, Fagiolini A, Iazzetta P, et al. Clinical evaluation of switching from immediate-release to prolonged-release lithium in bipolar patients, poorly tolerant to lithium immediate-release treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Brain Behav. 2022;12(3):e2485. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2485.

Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ. Reduction of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients during long-term treatment with lithium. In: Koslow SH, Ruitz P, Nemeroff CB, editors. A concise guide to understanding suicide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014. p. 217–28.

Barraclough B. Suicide prevention, recurrent affective disorder and lithium. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;121(563):391–2. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.121.4.391.

Jamison KR. Suicide and bipolar disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1986;487:301–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb27909.x.

Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, Floris G, Silvetti F, Tohen M. Lithium treatment and risk of suicidal behavior in bipolar disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(8):405–14. https://doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v59n0802.

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J. Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 5):44–52.

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Davis P, Pompili M, Goodwin FK, Hennen J. Decreased risk of suicides and attempts during long-term lithium treatment: a meta-analytic review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(5 Pt 2):625–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00344.x.

Ahrens B, Müller-Oerlinghausen B. Does lithium exert an independent antisuicidal effect? Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001;34(4):132–6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2001-15878.

Pompili M, Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, Germano L, Sarli G, Erbuto D, Baldessarini RJ. Lithium treatment versus hospitalization in bipolar disorder and major depression patients. J Affect Disord. 2023;1(340):245–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.028.

Cipriani A, Pretty H, Hawton K, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicidal behavior and all-cause mortality in patients with mood disorders: a systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(10):1805–19. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1805.

Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3646.

Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19(7):575–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12543.

Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Currier D, Grunebaum MF, Sher L, Sullivan GM, et al. Treatment of suicide attempters with bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial comparing lithium and valproate in the prevention of suicidal behavior. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1050–6. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010163.

Katz IR, Rogers MP, Lew R, Thwin SS, Doros G, Ahearn E, et al. Lithium treatment in the prevention of repeat suicide-related outcomes in veterans with major depression or bipolar disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2022;79(1):24–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.3170.

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Testing for antisuicidal effects of lithium treatment. JAMA Psychiat. 2022;79(1):9–10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.2992.

Pompili M, Vichi M, Dinelli E, Pycha R, Valera P, Albanese S, Lima A, De Vivo B, Cicchella D, Fiorillo A, Amore M, Girardi P, Baldessarini RJ. Relationships of local lithium concentrations in drinking water to regional suicide rates in Italy. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2015;16(8):567–74. https://doi.org/10.3109/15622975.2015.1062551.

Pompili M, Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, Germano L, Sarli G, et al. Lithium treatment versus hospitalization in bipolar disorder and major depression patients. J Affect Disord. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.028.

Stevens AWMM, Goossens PJJ, Knoppert-van der Klein EAM, Draisma S, Honig A, Kupka RW. Risk of recurrence of mood disorders during pregnancy and the impact of medication: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;249:96–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.018.

Viguera AC, Whitfield T, Baldessarini RJ, Newport DJ, Stowe Z, Reminick A, et al. Risk of recurrence in women with bipolar disorder during pregnancy: prospective study of mood stabilizer discontinuation. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(12):1817–24. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101639.

Rosso G, Albert U, Di Salvo G, Scatà M, Todros T, Maina G. Lithium prophylaxis during pregnancy and the postpartum period in women with lithium-responsive bipolar I disorder. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2016;19(2):429–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0601-0.

Munk-Olsen T, Liu X, Viktorin A, Brown HK, Di Florio A, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Maternal and infant outcomes associated with lithium use in pregnancy: an international collaborative meta-analysis of six cohort studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):644–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30180-9.

Patorno E, Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Cohen JM, Desai RJ, Mogun H, et al. Lithium use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac malformations. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2245–54. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1612222.

Fornaro M, Maritan E, Ferranti R, Zaninotto L, Miola A, Anastasia A, et al. Lithium exposure during pregnancy and the postpartum period: a systematic review and meta-analysis of safety and efficacy outcomes. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(1):76–92. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030228.

Gentile S. Prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder in pregnancy and breastfeeding: focus on emerging mood stabilizers. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8(3):207–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00295.x.