Abstract

Purpose

Working influences health; however, there is still insufficient exploration on how the two are associated. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether working time/week and industry type affect disability incidence in older adults.

Methods

In this study, we included data from 4679 participants aged ≥ 65 years. Working time/week and industry types were divided into < 20, 20–40, and > 40 h/week, and primary, secondary, and tertiary categories. Cox regression analysis was used to determine the association between working hours and industry type with disability incidence.

Results

After a median of 83 months, 836 (17.9%) experienced a disability. The effects of working hours and industry type on disability incidence were found to be associated with age and sex. Individuals who were 74 years and younger and who worked for 20–40 h/week had a lower risk of disability incidence compared with non-workers (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27–0.99); however, there was no statistically significant difference in those 75 years and older. Females and individuals aged 74 years and younger who worked in teriary industries has a lower risk of disability incidence compared with non-workers (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35–0.82: HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.81); however, no statistically significant difference was found in males or those 75 years and older.

Conclusions

Short working hours and tertiary industry employment were associated with a lower risk of developing disability, especially in females and those under 74 years. Paid work promotes physical health, but it is important to consider work hours and type of industry when choosing employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Determining factors for preventing functional disability is a critical goal for societies confronting rapidly aging populations, such as Japan. Social participation has been shown to be a factor in reducing the risk of functional disability [12, 35]. In Japan, 40.2% of older adults want to work, which is higher than US, Germany, and Sweden [2]. Working has a core role in “productive aging,” where the older population is not seen as a “burden” but can be engaged in activities that economically and socially contribute to society [9, 20]. Working in later years contributes to maintaining cognitive function, mental health, and physical function [8, 19, 23, 24, 27], through which disability development may be prevented. However, in previous reports, characteristics of low-quality jobs, such as unstable employment, physical labor, poor work control, effort-reward inequity, and long working hours, have been associated with physical and mental health problems in middle age [1, 15, 37, 41]. Additionally, some industry types have been reported to increase the risk of disease development. [11, 14, 43]. Although the association between some working conditions and health has been examined, the relationship between working time, industry type, and health in older adults remains unclear. Clarification of this relationship would help older adults choose employment.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate whether working time and industry type affect the incidence of disability in older adults. In Japan, it is clear that employment rates differ between males and females and that the purpose of joining the workforce is different [19]. Furthermore, older age increases the risk of developing diseases due to long working hours [14, 15]. Thus, we also examined the interaction of age and sex on the impact of working hours and industry type on disability incidence. We hypothesized that working would be effective in reducing the risk of disability, particularly in individuals who work for a short time or in tertiary industries. We also hypothesized that there would be an interaction effect between age and sex.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

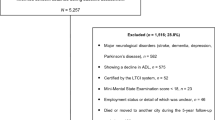

We used a prospective study design and recruited participants from the population-based cohort of the Obu Study of Health Promotion for the Elderly (OSHPE) [28], conducted from August 2011 to February 2012 at baseline. Each individual was recruited from Obu City, Japan. Obu City is a small city on the suburb of Nagoya, the third most populous city in Japan. Obu City has a population of 85,802, and 17.9% of the population is aged 65 or older. Among them, 53.6% are female and 41.4% are aged 75 and older (as of 1st October, 2011). The OSHPE inclusion criterion was being at least 65 years at examination. Before recruitment, we excluded 1661 people who had participated in another study, were hospitalized or in residential care, or had a certified care level of greater than 3 in the Japanese long-term care insurance (LTCI) system. OSHPE recruitment was conducted by sending a letter of invitation to a total of 14,313 eligible individuals, of whom 5104 ultimately participated (response rate: 35.7%). Among the individuals who agreed to participate, we excluded individuals who had certified LTCI (N = 130), a history of stroke (N = 258), Parkinsonism (N = 17), Alzheimer’s disease (N = 5), or baseline functional decline in basic activities of daily living (ADL; N = 15); ultimately, this resulted in the exclusion of 425 participants. Finally, we analyzed the data of 4679 older adults (median age, 71 [68–75] years, 28.6% over 75 years; 51.3% female). The Ethics Committee approved the study protocol, and we obtained informed consent from all participants before inclusion. This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2 Working time and industry type

Work status was assessed based on the participants' responses to the question, “Are you engaged in paid employment?” Additionally, data were collected on working time, frequency of work per week, and industry type. Working time was calculated by multiplying the hours worked per day by the number of working days per week. Then, the working time was divided into three categories: < 20 h/week, 20–40 h/week, and > 40 h/week. In Japan, 20 h/week is the standard time for eligibility for Social Security, and the Labor Standards Law specifies the standard workweek as 40 h. Industry types were categorized into primary (e.g., agriculture, forestry, and fisheries), secondary (e.g., manufacturing and construction), and tertiary industries (all those that are not classified as primary and secondary industries, e.g., financial, postal, medical, welfare, and service industries).

2.3 Determination of disability

Participants were monitored monthly for new cases of Japanese public LTCI certification, which was recorded by each municipality’s LTCI system. Individuals aged ≥ 65 years and those aged 40–64 years with age-related diseases are eligible for LTCI benefits in Japan. Upon application, an authorized care manager assesses the applicant’s physical and mental status using a standardized questionnaire, after which the certification board (comprising medical doctors and nurses) determines the required level of long-term care based on the anticipated care time and input from the applicant’s family physician. Disability was defined as an LTCI certification of any level, indicating a need for support or continuous care, based on the certification categories “Support Level 1 or 2” and “Care Level 1 to 5,” respectively [38].

2.4 Potential confounding factors

We chose age, sex, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, education, medication, living alone, frequency of trips outside the city, physical activity, smoking, results of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [7], scores from the 15-item version of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) [16, 26], usual gait speed, and social interaction (Do you talk to someone every day? Do you have a friend to call? Do you have any hobbies or do you participate in any sports activities? Do you have any experience with volunteering?) as possible confounding factors associated with ADL decline. In Japan, one of the most aged countries in the world, those aged 65 and over account for 28.8% of the population. In 2017, a working group of the Japan Geriatrics Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society published a recommendation that classified ages 65–74 as pre-old, ages 75–89 as old, and ages 90 + as oldest-old. Since Japan’s social security system rules are difference for those older than the age of 75, we set an age of 75 years as the cutoff value in our study. We assessed daily physical activity levels during the interview by asking participants about their daily walking time and used this as an indicator of their weekly physical activity level. Usual gait speed was measured using a detailed protocol described in a previous study [28]. Participants were instructed to walk at their usual walking speed. Two markers were used to indicate the start and end of a 2.4 m walk path, with a 2 m section to be traversed before passing the start marker so that participants were walking at a comfortable pace by the time they reached the timed path. Participants were asked to continue walking for an additional 2 m after the end of the path to ensure a consistent walking pace while on the timed path.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted separately for females and males. Demographic characteristics are presented as medians (interquartile ranges) or numbers (percentages). The Mann − Whitney U and chi-square tests were used to compare variables among the working and non-working groups. The Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted to identify different characteristics of working time and industry type. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. Missing data in all regression models were imputed using the “Mice” package in R [39]. The number of imputations was set to 50. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to evaluate the association of working time and industry type with disability incidence, adjusting for potential confounding factors. Previous studies have shown that age and sex interact with work status and health outcomes [6, 8, 19, 27, 30, 32, 37]. Therefore, a Cox regression analysis was used to confirm the interaction term between age, sex, and working hours or industry. We estimated adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for disability incidence. Stratified analysis by age and sex was performed if the interaction term was P < 0.1. Data management and statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) [13]. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3 Results

The final analysis included data from 4679 participants, with 836 (17.9%) participants developing a disability within 83 (81–85) months. Among the participants, 1386 (29.6%) older adults had paid work, of whom 633 (13.5%) worked < 20 h/week, 526 (11.2%) worked 20–40 h/week, and 218 (4.7%) worked > 40 h/week. A total of 124 (2.7%), 256 (5.5%), and 996 (21.3%) participants worked in primary, secondary, and tertiary industries, respectively (Table 1). The participants’ characteristics, which included some missing values, are shown in Table 2. Significant differences in age, sex, hypertension, medications, living alone, current alcohol consumption, current smoking, years of education, physical activity, frequency of trips outside the city, MMSE score, walking speed, GDS score, and social interaction were observed among working and non-working participants (P < 0.05). Factors related to time worked per week and industry type are presented in Online Resources 1 and 2.

In the cox proportional hazards regression models, 93 (2.0%) were imputed by the multiple imputation. Individuals who worked for 20–40 h/week and those who worked in tertiary industries had a lower risk of disability (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27–0.98: HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.80) than non-workers (Fig. 1). Interaction terms between working hours*age, industry type*age, and industry type*sex were associated with the occurrence of disability (P = 0.060, P = 0.003, P = 0.098). The association between working hours and disability incidence stratified by age is shown in Fig. 2. Individuals aged 74 years and younger who worked for 20–40 h/week had a lower risk of disability incidence compared with non-workers; however, there was no statistically significant difference in those aged 75 years and older (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.27–0.99: HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.66–1.90). The association between industry type and disability incidence stratified by age or sex is shown in Fig. 3. Females and individuals aged 74 years and younger who worked in teriary industries had a lower risk of disability incidence compared with non-workers; however, there was no statistically significant difference in males and those aged 75 years and older (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.35–0.82: HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.35–0.81: HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.49–1.20: HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.57–1.28).

4 Discussion

This study examined the disability incidence rate in a cohort of 4679 older adults. Of these participants, 836 (17.9%) experienced a disability during the observation period, which lasted until November 2018 (about 83 months). Approximately 30% of participants had paid work, with a median working time of 23 h/week (interquartile range, 12–35). Shorter working hours and tertiary industry employment were associated with a lower risk of developing disability; in particular, shorter working hours were associated with a lower risk of disability occurrence among those under 74 years of age, and working in tertiary industries was associated with a lower risk of disability among females and those under 74 years of age. The results of our study highlight the importance of older adults engaging in work activities that are not overwhelming while also maintaining contact with the community.

Several studies have reported on work and its association with health outcomes. Retirement has been associated with impaired ADL [18], whereas continuous employment has been linked to better maintenance of ADL [8, 30]. Consistent with previous research, this study found that working is effective in maintaining physical health in older adults. Additionally, the present study clarified the association between working hours, industry type, and the incidence of disability, which has not been examined in previous studies.

In this study, we found that working in tertiary industries had no statistically significant relationship with disability incidence in males. Previous studies have reported that work environments are only associated with lower instrumental ADL in males [37]. Conversly, Kee [14] reported that increased age, male sex, and industry type were associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorders. There are several reasons why the impact of work on physical health varies by sex. First, the reasons for seeking employment may differ by sex. This could be because females are more likely to prioritize social participation and well-being, whereas males may be more focused on paying debts or following family recommendations. [19]. Second, females are more likely to benefit from social participation [31, 32, 35, 36] and be better at building social connections in the workplace and community. Support from social connections is associated with fewer symptoms of depression [6].

Previous research indicates that work may be beneficial for health because it provides opportunities for physical activity and social interaction. Several randomized controlled trials have provided evidence that social participation can have positive effects on both mental and physical health [22]. Individuals who engage in social participation increase their physical activity, and this effect can last up to 3 years [33, 34]. Social isolation has been shown to have negative effects on health outcomesowing to it is associated with unhealthy behaviors, such as unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, smoking, and alcohol consumption [4, 21, 25, 29], which may lead to increased inflammatory responses due to chronic stress [17, 25, 42], immune system dysfunction [3, 5], and increased oxidative stress [3, 5, 10]. However, these are inferences, and the link between employment and disability, including the elucidation of mechanisms, needs to be examined in more detail.

In Japan, older adults are highly motivated to work, resulting in a gradual increase in their employment rate over time [2] The present study showed that taking into account working hours, type of industry, and sex when providing employment support may help prevent the occurrence of a disability. Moreover, providing detailed job descriptions should be encouraged, as different effects on mental and physical functioning have been reported depending on the physical or mental load of the job [40].

The strengths of this study include its large sample size and comprehensive assessment of medical history and mental, physical, and cognitive functions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between hourly working time, industry type, and disability incidence. However, this study also had sine limitations. First, the work status was assessed only at baseline, which may not accurately reflect changes in work status. Second, the cohort participants were relatively healthy older adults who had high health literacy and access to health checkups from their homes, and the analysis was conducted in a population that was younger and had fewer females than the target population. This study may have been subject to selection bias, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations. Third, this study did not examine other important work-related factors, such as skill use, job control, job security, and effort-reward fairness, which may also influence disability risk. Still, despite these limitations, this study may help identify measures to support employment for older adults. Fourth, the data were collected from one city and may have been influenced by policies related to the work environment and employment of older people in that city. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the relationship between work and disability incidence using data from multiple regions in the future. Finally, the study did not take into account socio-economic status, such as income, savings, and living arrangements, which should also be taken into account in the future.

In conclusion, short working hours and tertiary industry employment were associated with a lower risk of developing a disability, especially in females and individuals under 74 years of age. While paid work promotes physical health among older adults, it is important to consider work hours and type of industry when choosing employment.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40:5–18.

Cabinet Office Annual Report on the Aging Society. 2021. https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/english/annualreport/index-wh.html. 22/June/2023.

Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Goossens L, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:238–49.

Dean M, Raats MM, Grunert KG, Lumbers M. Factors influencing eating a varied diet in old age. Publ Health Nutr. 2009;12:2421–7.

Elovainio M, Lahti J, Pirinen M, Pulkki-Råback L, Malmberg A, Lipsanen J, et al. Association of social isolation, loneliness and genetic risk with incidence of dementia: UK biobank cohort study. BMJ Open. 2022;12: e053936.

Fiori KL, Denckla CA. Social support and mental health in middle-aged men and women: a multidimensional approach. J Aging Health. 2012;24:407–38.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S, Kobayashi E, Minami U, Suzuki H, Yoshida H, et al. Engagement in paid work as a protective predictor of basic activities of daily living disability in Japanese urban and rural community-dwelling elderly residents: an 8 year prospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16:126–34.

Herzog AR, Kahn RL, Morgan JN, Jackson JS, Antonucci TC. Age differences in productive activities. J Gerontol. 1989;44:S129–38.

Hsiao YH, Chang CH, Gean PW. Impact of social relationships on Alzheimer’s memory impairment: mechanistic studies. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25:3.

Ishihara R, Babazono A, Liu N, Yamao R. Impact of income and industry on new-onset diabetes among employees: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2022;19:1–14.

Kanamori S, Kai Y, Aida J, Kondo K, Kawachi I, Hirai H, et al. Social participation and the prevention of functional disability in older Japanese: the JAGES cohort study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9: e99638.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–8.

Kee D. Characteristics of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Korea. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2023;20:1024.

Kuroda S, Yamamoto I. Good boss, bad boss, workers’ mental health and productivity: evidence from Japan. Jpn World Econ. 2018;48:106–18.

Lesher EL, Berryhill JS. Validation of the geriatric depression scale–short form among inpatients. J Clin Psychol. 1994;50:256–60.

Loucks EB, Berkman LF, Gruenewald TL, Seeman TE. Relation of social integration to inflammatory marker concentrations in men and women 70 to 79 years. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1010–6.

Minami U, Nishi M, Fukaya T, Hasebe M, Nonaka K, Koike T, et al. Effects of the change in working status on the health of older people in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2015;10: e0144069.

Minami U, Suzuki H, Kuraoka M, Koike T, Kobayashi E, Fujiwara Y. Older adults looking for a job through employment support system in Tokyo. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0159713.

Morrow-Howell N, Wang Y. Productive engagement of older adults: elements of a cross-cultural research agenda. Ageing Int. 2013;38:159–70.

Naito R, McKee M, Leong D, Bangdiwala S, Rangarajan S, Islam S, et al. Social isolation as a risk factor for all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. PLoS ONE. 2023;18: e0280308.

Pettigrew S, Jongenelis MI, Jackson B, Warburton J, Newton RU. A randomized controlled trial and pragmatic analysis of the effects of volunteering on the health and well-being of older people. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020;32:711–21.

Reuter-Lorenz PA, Park DC. Human neuroscience and the aging mind: a new look at old problems. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65:405–15.

Schwingel A, Niti MM, Tang C, Ng TP. Continued work employment and volunteerism and mental well-being of older adults: Singapore longitudinal ageing studies. Age Ageing. 2009;38:531–7.

Shankar A, McMunn A, Banks J, Steptoe A. Loneliness, social isolation, and behavioral and biological health indicators in older adults. Health Psychol. 2011;30:377–85.

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol Aging Ment Health. 1986;5:165–73.

Shiba K, Kondo N, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Retirement and mental health: dose social participation mitigate the association? a fixed-effects longitudinal analysis. BMC Publ Health. 2017;17:526.

Shimada H, Makizako H, Doi T, Yoshida D, Tsutsumimoto K, Anan Y, et al. Combined prevalence of frailty and mild cognitive impairment in a population of elderly Japanese people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:518–24.

Stokes JE. Social integration, perceived discrimination, and self-esteem in mid- and later life: intersections with age and neuroticism. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23:727–35.

Sugihara Y, Sugisawa H, Shibata H, Harada K. Productive roles, gender, and depressive symptoms: evidence from a national longitudinal study of late-middle-aged Japanese. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2008;63:227–34.

Sun W, Watanabe M, Tanimoto Y, Shibutani T, Kono R, Saito M, et al. Factors associated with good self-rated health of non-disabled elderly living alone in Japan: a cross-sectional study. BMC Publ Health. 2007;7:297.

Takagi D, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Social participation and mental health: moderating effects of gender, social role and rurality. BMC Publ Health. 2013;13:701.

Tan EJ, Rebok GW, Yu Q, Frangakis CE, Carlson MC, Wang T, et al. The long-term relationship between high-intensity volunteering and physical activity in older African American women. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64:304–11.

Tan EJ, Xue QL, Li T, Carlson MC, Fried LP. Volunteering: a physical activity intervention for older adults–the experience corps program in baltimore. J Urban Health. 2006;83:954–69.

Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Association between social participation and 3 year change in instrumental activities of daily living in community-dwelling elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:107–13.

Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Hosoi H. Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: a community-based longitudinal study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73:799–806.

Tomioka K, Kurumatani N, Saeki K. Older adult males who worked at small-sized workplaces have an increased risk of decline in instrumental activities of daily living: a community-based prospective study. J Epidemiol. 2019;29:407–13.

Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:522–7.

Van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2011;45:1–67.

van den Bogaard L, Henkens K. When is quitting an escape? how different job demands affect physical and mental health outcomes of retirement. Eur J Publ Health. 2018;28:815–9.

Welsh J, Strazdins L, Charlesworth S, Kulik CT, Butterworth P. Health or harm? a cohort study of the importance of job quality in extended workforce participation by older adults. BMC Publ Health. 2016;16:885.

Yu B, Steptoe A, Chen LJ, Chen YH, Lin CH, Ku PW. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in patients with cardiovascular disease: a 10 year follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2020;82:208–14.

Zaitsu M, Cuevas AG, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Takeuchi T, Kobayashi Y, Kawachi I. Occupational class and risk of renal cell cancer. Health Sci Rep. 2018;1: e49.

Acknowledgements

We thank the research and healthcare staff involved in this study for their assistance with the assessments.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists, Japan (23K16666); Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Japan (Grant 23300205); Research Institute of Science and Technology for Society, the Solution-Driven Co-creative R&D Program for SDGs (SOLVE for SDGs): Preventing Social Isolation & Loneliness and Creating Diversified Social Networks, Japan (22-221037254); The Research Funding for Longevity Sciences from the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology (NCGG), Japan (Grants 22-16 and 21-16); and The Health Labour Sciences Research Grants from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (Grant H23-tyoujyu-ippan001). The funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript writing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Takahiro Shimoda has full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: Takahiro Shimoda, Kouki Tomida, and Hiroyuki Shimada. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors. Drafting of the manuscript: Takahiro Shimoda. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Takahiro Shimoda, Kouki Tomida, Chika Nakajima, Ayuka Kawakami, Takehiko Doi, and Hiroyuki Shimada. Statistical analysis: Takahiro Shimoda, Kouki Tomida, and Hiroyuki Shimada. Obtained funding: Kouki Tomida and Hiroyuki Shimada. Administrative, technical, or material support: Takahiro Shimoda, Chika Nakajima, Ayuka Kawakami, Takehiko Doi, and Hiroyuki Shimada. Supervision: Takehiko Doi and Hiroyuki Shimada.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of the National Center for Gerontology and Geriatrics approved the study protocol (registration number: 1440–5). This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Shimoda, T., Tomida, K., Nakajima, C. et al. Impact of working time and industry type on disability incidence among older Japanese adults. Discov Public Health 21, 10 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00136-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12982-024-00136-7