Abstract

Background

COVID-19 has not only taken a staggering toll in terms of cases and lives lost, but also in its psychosocial effects. We assessed the psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in a large cohort of people with HIV (PWH) in Washington DC and evaluated the association of various demographic and clinical characteristics with psychosocial impacts.

Methods

From October 2020 to December 2021, DC Cohort participants were invited to complete a survey capturing psychosocial outcomes influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some demographic variables were also collected in the survey, and survey results were matched to additional demographic data and laboratory data from the DC Cohort database. Data analyses included descriptive statistics and multivariable logistic regression models to evaluate the association between demographic and clinical characteristics and psychosocial impacts, assessed individually and in overarching categories (financial/employment, mental health, decreased social connection, and substance use).

Results

Of 891 participants, the median age was 46 years old, 65% were male, and 76% were of non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity. The most commonly reported psychosocial impact categories were mental health (78% of sample) and financial/employment (56% of sample). In our sample, older age was protective against all adverse psychosocial impacts. Additionally, those who were more educated reported fewer financial impacts but more mental health impacts, decreased social connection, and increased substance use. Males reported increased substance use compared with females.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had substantial psychosocial impacts on PWH, and resiliency may have helped shield older adults from some of these effects. As the pandemic continues, measures to aid groups vulnerable to these psychosocial impacts are critical to help ensure continued success towards healthy living with HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The toll in terms of lives lost from the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has been staggering, with close to 85 million reported cases and over 1 million deaths as of June 2022 in the United States (U.S.), and over 6.2 million deaths worldwide [1]. However, the psychosocial impacts of the pandemic are even wider-reaching than case and mortality counts indicate.

The psychological impacts (e.g., fear, stress, anxiety, depression) of COVID-19 [2,3,4,5,6,7] and efforts to limit the spread of COVID-19 (e.g., social distancing, quarantine, isolation, stay-at-home orders) [8] have resulted in widespread social disruption (e.g., school closure, unemployment, travel restriction, limited or virtual health care services) which may have the unintended consequence of exacerbating the psychological impact [9,10,11]. Psychiatric disorders and social challenges are also highly prevalent among people with HIV (PWH) [12, 13] and may be intensified by COVID-19.

Early evidence suggests widespread psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among PWH [14, 15]: income reduction [16, 17], disruptions in substance use treatment [18, 19], increased loneliness [20], particularly among women [21], and increased anxiety and depression symptoms [22,23,24].

The District of Columbia (DC) has been a COVID-19 hotspot at various points in the pandemic [25,26,27] and is an established HIV hotspot [28]. In this setting, we assessed the psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment measures in a large cohort of patients receiving HIV care in Washington DC. The overall framework for this research was the socio-ecological model [29]. This model considers the factors that are most likely to influence HIV-related behavior and outcomes, many of which may have been influenced by the pandemic. This analysis examined demographic and clinical characteristics associated with psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among PWH in Washington, DC. Our goal with this work was to explore who in DC was most vulnerable to psychosocial impacts due to the pandemic. We hypothesized that individuals who in older age groups would be most vulnerable to adverse psychosocial impacts of the pandemic. This analysis was primarily descriptive and lays the groundwork for future longitudinal analyses of HIV-related outcomes during the pandemic. This may ultimately help us tailor interventions to support people with HIV to maintain undetectable HIV RNA and to avoid adverse HIV-associated outcomes.

Methods

Setting and participants

The DC Cohort is a longitudinal observational cohort study of HIV-infected persons receiving care at 14 clinical sites in DC [28]. With over 11,000 enrolled participants, it is the largest city-wide cohort of PWH in the U.S. and is representative of PWH in DC, with the majority of participants being male and Black [28]. Patient-level data are routinely collected from electronic health records (EHRs) on socio-demographics, clinic visits, and clinical factors including laboratory values and prescribing information. Data are imported into a centralized database and processed into analytic files via SAS.

Recruitment and screening

Active DC Cohort participants aged 18 and older were approached in person or by telephone, email, or during a telehealth visit and provided additional information about a COVID-19 survey. A survey link was sent to interested participants via email or text. Participants were remunerated with a $25 gift card for their participation.

Survey

The COVID-19 survey is an ongoing a cross-sectional survey, with data collection starting October 30, 2020. Data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure, web-based software platform. The survey was available in both English and Spanish. Participants who did not have access to a computer or smartphone were administered the survey by phone. Informed consent was embedded in the survey which was approved by the George Washington University IRB. The survey included the following domains, adapted from existing instruments [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]: socio-demographics, healthcare access, pre-existing medical conditions, household contacts, COVID-19 symptoms and testing, impact of COVID-19, risk perceptions related to COVID-19, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, insomnia, tobacco product use, sexual risk behaviors, COVID-19 stigma, ART adherence, and telehealth. Validated instruments were used whenever available [31, 33, 38]. Additional file 1: Appendix 1 contains the survey instrument.

Variables of interest

Four domains of psychosocial impacts of COVID-19 were assessed:

-

1.

Financial/employment: household income decreased; lost health insurance; negative impact on paying rent/mortgage; negative impact on getting food; lost housing.

-

2.

Mental health: feeling anxious increased; quality of life decreased; quality of sleep decreased; response of “Yes” to anhedonia and/or depressed mood question on PHQ-2 screening [38].

-

3.

Decreased social connection: feeling connected to family decreased; feeling connected to friends decreased.

-

4.

Substance use: alcohol use increased; illicit drug use increased.

Participants indicated the degree to which they experienced each psychosocial impact using a four-point scale (highly increased, increased, decreased, highly decreased). Responses were collapsed such that “increased” and “highly increased” were combined to “increased” while responses of “decreased” and “highly decreased” were combined to “decreased.” The psychosocial impacts were first examined individually (13 responses in the 4 domains above). Subsequently, they were examined by domain. If a respondent selected “yes” to at least one response in a given domain, that domain was considered impacted.

Demographic and clinical characteristics from the COVID survey included: age (categorical: 16–38 years; 39–49 years; 50 + years), gender identity (male; female), race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Black; Non-Hispanic white; Hispanic, any race; other), education (at least some high school; at least some college), self-reported underlying medical conditions (0 or ≥ 1), and year of survey completion. All participants completed the survey once. Some completed it in the calendar year 2020 and others completed it in the calendar year 2021.

Additional demographic and clinical characteristics included the following from the DC Cohort database: HIV mode of transmission (men who have sex with men (MSM), high risk heterosexual (HRH), IDU, or a composite group “Other” consisting of none, missing, or unknown), duration of HIV infection, and most recent measure (between 1/12020 and 12/31/2021) of CD4 cell count (cells/µl) and HIV RNA suppression (viral suppression (VS)).

Statistical analysis

Analyses for this study included survey data through December 31, 2021 linked to DC Cohort medical record data. Statistical analyses included descriptive statistics. Results are shown as frequencies (%) for categorical variables and median (interquartile range (IQR)) for variables.

Multivariable logistic regressions to evaluate the association between demographic and clinical characteristics and the psychosocial impacts were performed for the financial/employment, mental health, decreased social connection, and substance use variables individually and as overarching domains.

Adjusted Odds Ratios (aOR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (95% CI) were estimated by adjusting for age, gender, HIV transmission risk, race/ethnicity, education, self-reported underlying conditions, VS, CD4, and survey year. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

An additional multivariable logistic regression model for psychosocial impact category was fit excluding CD4 and VS status. We performed the additional modeling because not all survey respondents had a CD4 count and/or HIV RNA and we wanted to evaluate the demographic and clinical characteristic associations in the overall sample, regardless of whether lab values were present. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

During the survey period, 891 participants completed the survey. The response rate was 41%. Of those, 748 had a CD4 value available and 751 had an HIV RNA lab value available (last measured value after 1/1/20 through 12/31/21). As shown in Table 1, the median age of the sample was 46 years old. Most participants (75.7%) were of non-Hispanic Black race/ethnicity. Over half (55.6%) were employed full-or part-time as of 1/1/20. Most of the sample for whom HIV RNA results were available was virally suppressed (717/748, or 95.9%).

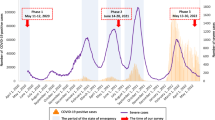

The results for each psychosocial impact category will be discussed in the text, which reference relevant information from the following sources: Tables 2, 3; Fig. 1.

Psychosocial impact category: financial/employment

As shown in Table 2, the overall prevalence of negative financial/employment impact was 55.7%, with a decrease in household income being reported as the most prevalent individual response (34.3%).

Figure 1 illustrates factors associated with individual responses within the financial/employment impact domain. Figure 1 shows that females were less likely to lose their health insurance than males. In addition, Fig. 1 shows that HRH were more likely to report a negative impact on paying rent and/or mortgage than MSM, and those with suppressed HIV RNA were less likely to report losing their housing compared to those with unsuppressed HIV RNA.

Table 3 examines the overall financial/employment domain, and demonstrates that older age was inversely associated with an adverse financial/employment impact (aOR per 10 year age increase 0.76, 95% CI 0.63, 0.90), p = 0.0022). In addition, compared to those who had completed at least some high school, those who had completed at least some college were less likely to report negative financial/employment impact (aOR 0.58, 95% CI 0.41, 0.84, p = 0.0037). Finally, individuals who were virally suppressed were less likely to report a negative financial/employment impact (aOR 0.48, 95% CI 0.23, 1.00, p = 0.0490).

Psychosocial impact category: mental health

Table 2 shows that 77.7% of respondents overall reported a negative mental health impact. Feeling anxious (49.9%) and reporting decreased quality of life (46.6%) were most common.

Comparisons in Fig. 1 demonstrate that Hispanic individuals were more likely to report increased anxiety compared to non-Hispanic white individuals. Also, individuals with suppressed HIV RNA were less likely to report feelings of anhedonia/depression than individuals with unsuppressed HIV RNA.

Table 3 demonstrates that older age was inversely associated with an adverse mental health impact (aOR per 10 year age increase 0.72, 95% CI 0.58, 0.89), p = 0.0031).

Additionally, compared to those who had completed at least some high school, those who had completed at least some college were more likely to report a negative mental health impact (aOR 1.74, 95% CI 1.13, 2.67, p = 0.0121). Finally, compared to non-Hispanic White individuals, non-Hispanic Black individuals were less likely to report a negative mental health impact (aOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.35, 1.25, p = 0.1998), though this finding only achieved statistical significance in multivariable models which did not include lab values, as there were more participants included in those models (data not shown).

Psychosocial impact category: decreased social connection

The overall prevalence of reporting decreased social connection was 51.7% (Table 2). A decrease in connections to friends (48.1%) was reported more frequently than a decrease in connections to family (38.7%).

Table 3 demonstrates that older age was inversely associated with reporting decreased social connection (aOR per 10 year age increase 0.77, 95% CI 0.64, 0.91), p = 0.0030) Additionally, compared to those who had completed at least some high school, those who had completed at least some college were more likely to report decreased social connection (aOR 1.48, 95% CI 1.04, 2.11, p = 0.0285). Compared to non-Hispanic White individuals, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other races were less likely to report decreased social connection (p-values p = 0.0014, p = 0.0016, and p = 0.0015, respectively). Lastly, comparing results of the one-time survey that were completed in 2021, survey respondants in 2020 were more likely to report decreased social connection (aOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.14, 2.85, p = 0.0120).

Psychosocial impact category: substance use

Table 2 highlights the 17.9% overall prevalence of adverse substance use impact. An increase in alcohol use (15.1%) was more commonly reported than increased illicit drug use (8.2%).

Figure 1 demonstrates that individuals with suppressed HIV RNA were less likely to report increased substance use.

Table 3 demonstrates that older age was inversely associated with reporting increased substance use (aOR per 10 year age increase 0.72, 95% CI 0.56, 0.92), p = 0.0094) CCompared to those who had completed at least some high school, those who had completed at least some college were more likely to report increased substance use (aOR 3.29, 95% CI 1.82, 5.97, p < 0.0001). Finally, compared to males, females were less likely to report increased substance use (aOR 0.41, 95% CI 0.20, 0.86, p = 0.0182).

Discussion

In this city-wide longitudinal cohort, many PWH reported psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including increased anxiety, decreased quality of life, financial difficulties, and feelings of isolation. As the pandemic continues and some emergency supports that were established early in the pandemic are removed, vulnerable individuals who are already at risk for worse HIV outcomes may suffer more. Considering the socio-ecological model [29], factors at all levels (individual, interpersonal, community, institutional and structural) can influence health outcomes. The factors examined in this study were primary individual and interpersonal; the DC Cohort also has ongoing investigations of institutional and health system level responses to the pandemic that may have influenced HIV outcomes. To continue to advance the goals of the Ending the HIV epidemic, i.e., to keep people with HIV on therapy so that they maintain viral suppression and do not transmit the virus to others, understanding and addressing these factors is key.

Adverse psychosocial impacts of the pandemic among PWH have been previously reported [14]. In our sample, a large number of respondents (27%) reported difficulty getting food, and even more (29%) reported difficulty paying rent/mortgage. Even pre-pandemic, housing costs in the DC metropolitan area were rising at a faster pace than incomes [39], and unstable housing or homelessness was associated with worse HIV outcomes [40,41,42].

Multiple studies have demonstrated increased stress and mental health symptoms among PWH resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic [15, 43]. Many of our respondents reported increased feelings of anxiety and decreased sleep quality. Over one-third (36%) of our participants reported one or two of the hallmark symptoms of depression, anhedonia, or depressed mood. This is similar to other research groups’ findings during the pandemic. In a multinational sample, 28% of people with HIV had a positive screen for depression [22]. A large survey of MSM in the US, 10% of whom had HIV, showed that 72% had increased anxiety as a result of the pandemic [44]. The escalation of anxiety due to the pandemic has many possible explanations: concern regarding contracting COVID-19 and the potentially increased severity of COVID-19 among PWH, finances, and access to care, among others [15].

The AGEhIV Cohort in the Netherlands, which includes participants aged 45 and older at time of enrollment (2010–2012), also examined the impact of social distancing as a result of the pandemic and health-related quality of life, depressive symptoms [45]. They described additional psychosocial impacts as well. The investigators found that PWH were more likely to report increased alcohol use. About 8.5% reported clinically significant depressive symptoms, with no difference by HIV status. Concerns about getting ill with COVID were inversely associated with self-reported health-related QOL and associated with depressive symptoms.

Another major impact of the pandemic was on social isolation and loneliness. Individuals with HIV are already at increased risk of loneliness due to the stigma surrounding HIV [46], and our results, as well as others, have demonstrated increased social isolation, with respondents noting feeling disconnected from family and friends [20].

Looking across the domains examined, older age was protective against adverse outcomes in all four domains. Prior research has shown similar findings [47,48,49,50,51], and those findings have attributed to increased resilience in older adults that allows them to weather stressors better. Younger people with HIV often fare worse in terms of HIV care continuum outcomes [52], stemming from less stability in their social situations. Given the domains of interest in this analysis: financial/employment, mental health, decreased social connection, and increased substance use, older age is likely protective against these impacts due to having more life experience, being better able to navigate systems to maintain benefits and/or connect with needed resources, and less susceptibility to substance use.

Education had various effects on the psychosocial impacts. Individuals with more education were less likely to have financial/employment impacts, possibly reflecting that these individuals were able to continue their employment working at home. Fields that were particularly impacted by the pandemic included hospitality and food service industry jobs [53], which are typically filled by individuals with lower education level. The opposite effect of education on other impacts was demonstrated, i.e., individuals with higher education level were more likely to have mental health, social connection, or increased substance use impacts. The cause of these findings is likely multifactorial. Assuming that individuals with higher education levels are more likely to have jobs that allow them to work from home, increased mental health issues may have been related to working from home and balancing other responsibilities simultaneously. Alternatively, individuals with higher education may be employed in a health care setting, which was a particularly stressful environment during the pandemic. Decreased social connection among individuals with higher education may result from having the resources to live alone, be working alone at home, and not being able to go to social events. Individuals with higher levels of education may have had increased levels of substance use due to more isolation.

While a limitation of this study is the lack of longitudinal HIV outcomes data, strengths include the large sample size and the use of laboratory results from the DC Cohort database. Future directions include examining the impact of psychosocial factors on the entire HIV care cascade and generating evidence for measures supporting mental health and easing the psychosocial impact of the pandemic among PWH [16, 54, 55]. In conclusion, we must ensure that the most vulnerable have access to the resources they need to maintain their health as the pandemic persists.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available to protect the confidentiality of participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

COVID-19 Map. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resour. Cent. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao M, Wang Z, Xie B, Xu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33: e100213.

Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, Kurosawa M, Benedek DM. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74:281–2.

Li W, Yang Y, Liu Z-H, Zhao Y-J, Zhang Q, Zhang L, et al. Progression of Mental Health Services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1732–8.

Jiloha R. COVID-19 and mental health. Epidemiol Int E-ISSN. 2020;2455–7048(5):7–9.

WHO. No Title.

CDC. COVID-19 and Your Health. Cent. Dis. Control Prev. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet Lond Engl. 2020;395:912–20.

Abel T, McQueen D. The COVID-19 pandemic calls for spatial distancing and social closeness: not for social distancing! Int J Public Health. 2020;65:231–231.

Keeping your distance to stay safe. https://www.apa.org. https://www.apa.org/practice/programs/dmhi/research-information/social-distancing. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

Orlando M, Burnam MA, Beckman R, Morton SC, London AS, Bing EG, et al. Re-estimating the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a nationally representative sample of persons receiving care for HIV: results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2002;11:75–82.

Weaver MR, Conover CJ, Proescholdbell RJ, Arno PS, Ang A, Ettner SL. Utilization of mental health and substance abuse care for people living with HIV/AIDS, chronic mental illness, and substance abuse disorders. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:449–58.

Winwood JJ, Fitzgerald L, Gardiner B, Hannan K, Howard C, Mutch A. Exploring the social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people living with HIV (PLHIV): a scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:4125–40.

Barbera LK, Kamis KF, Rowan SE, Davis AJ, Shehata S, Carlson JJ, et al. HIV and COVID-19: review of clinical course and outcomes. HIV Res Clin Pract. 2021;22:102–18.

Sherbuk JE, Williams B, McManus KA, Dillingham R. Financial, food, and housing insecurity due to coronavirus disease 2019 among at-risk people with human immunodeficiency virus in a nonurban Ryan white HIV/AIDS program clinic. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7:1–5.

Jones DL, Ballivian J, Rodriguez VJ, Uribe C, Cecchini D, Salazar AS, et al. Mental health, coping, and social support among people living with HIV in the Americas: a comparative study between Argentina and the USA during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:2391–9.

Ballivian J, Alcaide ML, Cecchini D, Jones DL, Abbamonte JM, Cassetti I. Impact of COVID-19-related stress and lockdown on mental health among people living with HIV in Argentina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2020(85):475–82.

Hochstatter KR, Akhtar WZ, Dietz S, Pe-Romashko K, Gustafson DH, Shah DV, et al. Potential influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on drug use and HIV care among people living with HIV and substance use disorders: experience from a Pilot mHealth Intervention. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:354–9.

Marziali ME, Card KG, McLinden T, Wang L, Trigg J, Hogg RS. Physical distancing in COVID-19 may exacerbate experiences of social isolation among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2250–2.

Jones DL, Morgan KE, Martinez PC, Rodriguez VJ, Vazquez A, Raccamarich PD, et al. COVID-19 burden and risk among people with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;2021(87):869–74.

SieweFodjo JN, FariadeMouraVillela E, VanHees S, Vanholder P, Reyntiens P, Colebunders R. Follow-up survey of the impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV during the second semester of the pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4635. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094635.

Cooley SA, Nelson B, Doyle J, Rosenow A, Ances BM. Collateral damage: impact of SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in people living with HIV. J Neurovirol. 2021;27:168–70.

Wion RK, Miller WR. The impact of COVID-19 on HIV self-management, affective symptoms, and stress in people living with HIV in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2021;25:3034–44.

Deaths in the DMV increase as officials warn it could be next hot spot. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/deaths-in-dmv-increase-as-officials-warn-it-could-be-next-hot-spot/2020/04/06/9863defa-77b2-11ea-b6ff-597f170df8f8_story.html.

Officials Warn D.C. Could Be The Next Coronavirus ‘Hot Spot.’ What Does That Mean? https://dcist.com/story/20/04/07/officials-warn-d-c-could-be-the-next-coronavirus-hot-spot-what-does-that-mean/.

White House says D.C. region among worst in country, as summer closures continue. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/white-house-says-dc-region-among-worst-in-country-as-summer-closures-continue/2020/05/22/31e4cc8c-9c3a-11ea-ac72-3841fcc9b35f_story.html.

HHS. Ending the HIV Epidemic Counties and Territories. 2019.

Kaufman MR, Cornish F, Zimmerman RS, Johnson BT. Health behavior change models for HIV prevention and AIDS care: practical recommendations for a multi-level approach. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:S250.

Kaiser Permanente Research Bank COVID-19 Surveys. 2020; https://researchbank.kaiserpermanente.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/KPRB-COVID-19-Survey_-summary.pdf.

Wilbourn B, Saafir-Callaway B, Jair K, Wertheim JO, Laeyendeker O, Jordan JA, et al. Characterization of HIV risk behaviors and clusters using HIV-transmission cluster engine among a cohort of persons living with HIV in Washington, DC. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2021;37:706–15.

Stanford University. COVID19 Interview Items for Vulnerable Populations. 2020; Available from https://clelandcm.github.io/COVID19-Interview-Items/COVID-Items.html#stanford. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

Kalichman S. Kalichman Covid-19 Assessment. 2020; Available from https://clelandcm.github.io/COVID19-Interview-Items/COVID-Items.html#kalichman-covid-19-assessment. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

COVID-19 Household Environment Scale. Available from https://elcentro.sonhs.miami.edu/research/measures-library/ches/ches-eng/index.html. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

ATN COVID Questionnaire. https://clelandcm.github.io/COVID19-Interview-Items/COVID-Items.html#atn.

Human Infection with 2019 Novel Coronavirus Case Report Form Interviewer Information Case Classification and Identification. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/pui-form.pdf.

Baseline Questionnaire for the Communities, Households and SARS/COV-2 Epidemiology (CHASE) COVID Study. 2020. https://cunyisph.org/wp-content/uploads/CHASE-COVID_baseline_V2.1.pdf.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–92.

District of Columbia Eligible Metropolitan Area Integrated HIV/AIDS prevention and care plan. https://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/service_content/attachments/DC%20DOH%20INTEGRATED%20PLAN_FINAL.pdf.pdf.

Wainwright JJ, Beer L, Tie Y, Fagan JL, Dean HD. Socioeconomic, behavioral, and clinical characteristics of persons living with HIV who experience homelessness in the United States, 2015–2016. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:1701–8.

Aidala AA, Lee G, Abramson DM, Messeri P, Siegler A. Housing need, housing assistance, and connection to HIV medical care. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:101–15.

Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and housed people living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:2238–45.

Kunzler AM, Röthke N, Günthner L, Stoffers-Winterling J, Tüscher O, Coenen M, et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analyses. Glob Health. 2021;17:34.

Sanchez TH, Zlotorzynska M, Rai M, Baral SD. Characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on men who have sex with men across the United States in April, 2020. AIDS Behav. 2020;24:2024–32.

Schaaf REA, Verburgh ML, Boyd A, Wit FW, Nieuwkerk PT, Schim van der Loeff MF, et al. Change in substance use and the effects of social distancing on health-related quality of life and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in people living with and without HIV. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Published Online First: 9900.https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/9900/Change_in_substance_use_and_the_effects_of_social.77.aspx.

Grov C, Golub SA, Parsons JT, Brennan M, Karpiak SE. Loneliness and HIV-related stigma explain depression among older HIV-positive adults. AIDS Care. 2010;22:630–9.

Czeisler MÉ. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6932a1.

Ups and Downs of Daily Life During COVID-19: Age Differences in Affect, Stress, and Positive Events|The Journals of Gerontology: Series B|Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article/76/2/e30/5872612?login=false. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

van Tilburg TG, Steinmetz S, Stolte E, van der Roest H, de Vries DH. Loneliness and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study among dutch older adults. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76:e249–55.

Vahia IV, Jeste DV, Reynolds CF III. Older adults and the mental health effects of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:2253–4.

Pearman A, Hughes ML, Smith EL, Neupert SD. Age differences in risk and resilience factors in COVID-19-related stress. J Gerontol Ser B. 2021;76:e38–44.

Kapogiannis BG, Koenig LJ, Xu J, Mayer KH, Loeb J, Greenberg L, et al. The HIV continuum of care for adolescents and young adults attending 13 Urban US HIV Care Centers of the NICHD-ATN-CDC-HRSA SMILE Collaborative. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2020;84:92–100.

COVID-19 recovery in hardest-hit sectors could take more than 5 years|McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/coronavirus-leading-through-the-crisis/charting-the-path-to-the-next-normal/covid-19-recovery-in-hardest-hit-sectors-could-take-more-than-5-years. Accessed 18 Aug 2022.

Davison KM, Thakkar V, Lin SL, Stabler L, MacPhee M, Carroll S, et al. Interventions to support mental health among those with health conditions that present risk for severe infection from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a scoping review of English and Chinese-language literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:7265. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147265.

Armbruster M, Fields EL, Campbell N, Griffith DC, Kouoh AM, Knott-Grasso MA, et al. Addressing health inequities exacerbated by COVID-19 among youth with HIV: expanding our toolkit. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med. 2020;67:290–5.

Acknowledgements

Data in this manuscript were collected by the DC Cohort Study Group with investigators and research staff located at: Children's National Hospital Pediatric clinic (Natella Rakhmanina); the Senior Deputy Director of the DC Department of Health HAHSTA (Clover Barnes); Family and Medical Counseling Service (Angela Wood); Georgetown University (Princy Kumar); The George Washington University Biostatistics Center (Marinella Temprosa, Vinay Bhandaru, Tsedenia Bezabeh, Nisha Grover, Lisa Mele, Susan Reamer, Alla Sapozhnikova, and Greg Strylewicz); The George Washington University Department of Epidemiology (Shannon Barth, Morgan Byrne, Amanda Castel, Alan Greenberg, Shannon Hammerlund, Paige Kulie, Anne Monroe, James Peterson, and Bianca Stewart) and Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics (Yan Ma); The George Washington University Medical Faculty Associates (Jose Lucar); Howard University Adult Infectious Disease Clinic (Jhansi L. Gajjala) and Pediatric Clinic (Sohail Rana); Kaiser Permanente Mid-Atlantic States (Michael Horberg); La Clinica Del Pueblo (Ricardo Fernandez); MetroHealth (Duane Taylor); Washington Health Institute, formerly Providence Hospital (Jose Bordon); Unity Health Care (Gebeyehu Teferi); Veterans Affairs Medical Center (Debra Benator); Washington Hospital Center (Glenn Wortmann); and Whitman-Walker Institute (Stephen Abbott).

Funding

The DC Cohort is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, UM1 AI069503 and 1R24AI152598-01. Drs. Monroe, Castel and Greenberg received funding and support from the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research (P30AI117970)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

AEG, ADC, and AKM designed the study, PEK, MEB, BCW, SKB, JBR processed the data, performed the analysis, and designed the tables and figures. AEG, ADC, AKM, MAH, DMH aided in interpreting the results. AKM took the lead in writing the manuscript with assistance from JBR and AEG. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the George Washington University IRB (#071029).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Monroe, A.K., Kulie, P.E., Byrne, M.E. et al. Psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic from a cross-sectional Survey of people living with HIV in Washington, DC. AIDS Res Ther 20, 27 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00517-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-023-00517-z