Abstract

Background

The presence of meningeal ectopic lymphoid structures (ELS) in a subgroup of patients diagnosed with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) corresponds to a pronounced cortical inflammation and an aggravated disease course. In MP4-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS), B cell aggregates develop in the central nervous system (CNS) in the chronic stage of the disease. Therefore, the model is suitable for studying key molecules of ELS development and maintenance. Here, we investigated whether there is a specific cytokine and chemokine signature in paired cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum samples associated with the presence of cerebellar B cell and T cell pathology and B cell aggregates of MP4-immunized mice.

Methods

Paired CSF and serum samples were collected from the cisterna magna and periphery of MP4-immunized mice at the chronic stage of disease. A control group with mice immunized only with the adjuvant (vehicle) was included in the study. A selected panel of 34 cytokines and chemokines were measured by MAGPIX® for both cohorts. For the assessment of B cell and T cell infiltration, immunohistochemical staining was performed and analyzed using light microscopy. To detect specific chemokine receptors additional staining was conducted.

Results

While we detected several upregulated cytokines and chemokines in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice independent of the extent of B cell and T cell pathology compared to vehicle-immunized mice, C-C motif chemokine ligand (CCL)-1 was associated with high B cell and T cell infiltration. Furthermore, the level of certain chemokines, including CCL1, CCL5, CCL7, CCL12, CCL22 and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand (CXCL)-13, was significantly increased (p < 0.05) in MP4-immunized mice showing a high number of B cell aggregates. While C-C motif chemokine receptor (CCR)5 had a ubiquitous expression independent of the extent of B cell and T cell pathology, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor (CXCR)-5 and CXCR6 expression was specifically associated with high B cell and T cell pathology.

Conclusion

Our data suggest that multiple cytokines and chemokines are involved in the pathophysiology of MP4-induced EAE. Furthermore, the presence of B cell aggregates was associated with a specific chemokine profile in the CSF, which might be useful for predicting the presence of these aggregates without the necessity to histologically screen the CNS tissue.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a neuroinflammatory autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS). Historically, the pathogenesis of MS has been considered to be driven by T cells [1]. However, with the development and success of CD20+ cell-depleting therapies, B cells have been catapulted into taking the center stage in the field of MS research [2]. The involvement of B cells in the pathophysiology of MS also comes from neuropathological studies of autopsied brain tissue from MS patients [3, 4]. For instance, meningeal ectopic lymphoid structures (ELS) have been detected in up to 40% of patients with secondary progressive MS (SPMS). These ELS displayed characteristics similar to that of secondary lymphoid organs (SLO), including the presence of follicular dendritic cells (FDC) and proliferating B cells. The association of these structures with a high degree of cortical pathology and a more severe disease course indicates a potential clinical relevance of ELS in MS progression [5].

However, the development and maintenance of ELS in MS is poorly understood. One study has shown that B-cell activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family (BAFF), which is important for long-term survival and persistence of B cells, can be locally produced by astrocytes in MS lesions thereby possibly aiding in the survival of B cells in the inflamed CNS [6]. Meanwhile, CXCL13 was found to be elevated in the CSF of relapsing–remitting MS patients (RRMS) and correlated with the presence of B cells and plasmablasts [7]. This link between the elevated CXCL13 level and the increased number of B cells in the CSF also suggests that CXCL13 may be an important B cell chemoattractant in the inflamed MS brain. Additionally, CXCL13 has been detected in ELS of SPMS patients [5, 8]. Finally, SPMS patients with high meningeal inflammation and grey matter pathology showed higher levels of TNF, lymphotoxin (LT)-α and CXCL13 in the CSF compared to patients with less pathology [9].

Owing to the limited access to well-characterized CNS tissue containing ELS from MS patients and corresponding CSF samples, several studies have focussed on EAE, the animal model of MS, to identify key molecules and mechanisms involved in ELS formation and maintenance [10]. For example, TH17 cells have been suggested to initiate the development of ELS in the CNS [11]. There is also evidence that a combination of TH17 cell-related cytokines, like interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22, as well as LT signaling are involved in the ELS formation process [12]. Other studies using animal models have identified molecules like interferon (IFN)-γ, TNF and CXCL13 to be involved in the development and maintenance of these structures [13,14,15].

Here we focused on MP4-induced EAE, a mouse model of MS, which is characterized by the development of B cell aggregates especially in the chronic stage of the disease [16, 17]. Using this model, we set out to identify relevant cytokines and chemokines, which may play a key role in the formation and maintenance of B cell aggregates, by analyzing paired CSF and serum samples in the chronic stage of MP4-induced EAE. To this end, we modified a method to collect CSF samples from mice [18], performed cytokine/chemokine multiplex assays and systematically characterized the extent of B cell and T cell pathology in the cerebellum, where pathology predominantly develops in the MP4 model [17]. Our data reveal a specific chemokine profile associated with the presence of B cell aggregates in the CNS of MP4-immunized mice.

Materials and methods

Mice

Female 7-week-old wild-type (WT) C67BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Animals were kept under specific pathogen-free conditions at the Preclinical Experimental Center for Animals (PETZ) of the Franz-Penzoldt Center (FPZ) of the University Hospital Erlangen with unrestricted access to water and a standard rodent diet (ssniff Spezialdiäten, Soest, Germany). Special care such as ClearH2O HydroGel (ClearH2O, Portland, ME, USA) was provided for mice displaying paralytic symptoms. All animal experiments were approved by the Regierung von Unterfranken (approval number 55.2-2531.01-91/14) and performed in accordance with the German law on the protection of animals, the “Principles of laboratory animal care” (NIH publication no. 86–23, revised 1985) and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

EAE induction and assessment of the disease course

All animals were between 10 to 15 weeks of age at the time of immunization. For EAE induction, incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) was prepared by mixing mineral oil (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and mannide monooleate (Merck) at a ratio of 9:1. For the preparation of complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA), Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37 Ra (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was added to IFA at a concentration of 5 mg/ml. MP4 (Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Boston, MA, USA) was emulsified in CFA and each mouse received a total dose of 200 μg of MP4 in a volume of 200 μl which was subcutaneously injected into both sides of the flank. Vehicle mice (control group) received a total volume of 200 μl CFA and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Merck) at a ratio of 1:1. Both the MP4-immunized cohort and the vehicle mice additionally received 100 ng of pertussis toxin (Hooke Laboratories Inc., Lawrence, MA, USA) by intraperitoneal injection at the day of immunization and 24 h later. To study the level of chemokine/cytokine changes in the CSF and periphery associated with the chronic stage of the disease (chronic MP4-induced EAE), mice were scored daily over a period of approximately 65 days after immunization and killed at 66.13 ± 1.83 days. Vehicle mice were killed at day 62 following immunization. For assessment of the disease course, we used the standard EAE scoring system: no symptoms (0), floppy tail (1), partial hind limb weakness (2), full hind limb paralysis (3), quadriplegia (4) and moribund (5). Increments of 0.25 were used to account for symptoms that were not clearly defined by the five categories. However, mice with a disease score ≥ 3 for more than 5 days were killed and excluded from the study.

Preparation of sample material

Serum

Up to seven drops of blood were collected from the tail vein of each mouse one day prior to killing. Blood was allowed to clot at room temperature (RT) for 30–45 min and serum was collected by centrifugation at 1000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. After carefully transferring the serum, another centrifugation step at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C was performed. Serum samples were immediately aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C until further analysis.

CSF

CSF sampling was adapted from the method of Boris Šakić using a self-constructed device (Fig. 1A) [18]. Briefly, a 1-ml syringe was shortened, and a ball of cotton was inserted as a filter. The syringe with the filter, which served as the mouthpiece, was fixed on a micromanipulator (Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab., Tokyo, Japan) using a three-way stopcock (Fig. 1A). Mice were killed with carbon dioxide (CO2) and placed in a prone position on the micromanipulator device. A sagittal incision of the skin at the occiput was made and the cranial bone was carefully removed. With the help of a microscope, the subcutaneous tissue, neck muscles and ligaments were separated to allow access to the cisterna magna, which is an extended cavern of the subarachnoid space filled with CSF (Fig. 1B). The dura mater of the cisterna magna was carefully pierced using a long glass capillary with an outer diameter of 1 mm and a narrowed tip. This allowed the CSF to flow into the capillary. Care was taken to adjust the capillary using the micromanipulator to precisely puncture the cisterna magna and avoid blood contamination. To obtain the maximum volume of CSF (range between 2.3 µl and 16 µl), this procedure was repeated until the cisterna magna was empty. After collection, each sample was briefly centrifuged, the supernatant was aliquoted and immediately stored at − 80 °C.

Procedure for the collection of cerebrospinal fluid from the cisterna magna. A The device for collecting CSF consisted of different components as displayed. B The CSF-filled cisterna magna was located at the back of the head and appeared as a dark triangle under the microscope. CSF cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebellum

Following CSF withdrawal, the whole brain was removed, and the cerebellum was carefully dissected using a scalpel. Tissue fixation of each cerebellum was done with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 48 h at 4 °C on a shaker. Following fixation, the tissues were washed in phosphate (PO4) buffer, dehydrated and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Serial sections were cut at a thickness of 5 µm and every fifth section (30 sections per mouse) was stained for B cells and T cells to assess pathology. Created with BioRender.com.

Immunohistochemistry and assessment of pathology

B cell and T cell staining

B cell and T cell staining of the cerebellar tissue sections was done according to the protocol previously described by our group with slight modifications [19]. Briefly, sections were deparaffinized using xylene and rehydrated in a descending series of isopropanol solution. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 15 min. Tissue sections were washed with Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-T (TBS + 0.1% Tween 20) between every incubation and antibodies were diluted according to Table 1. Sections were blocked for 30 min at RT followed by an incubation with an anti-CD3 antibody for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, a biotinylated anti-rabbit antibody was added, and the sections were incubated for 1 h at RT. Streptavidin coupled to alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted in TBS (1:500) was applied on the sections for 30 min at RT. The sections were developed for 40 min at RT using the Vector BCIP/NBT Kit (Vector Laboratories) until blue stained CD3+ cells were visible under a light microscope. An anti-CD45R (B220) antibody was used to detect B cells on the same sections. Following an overnight incubation at 4 °C with the second primary antibody, a biotinylated anti-rat antibody was applied on the tissue sections for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, the sections were incubated with streptavidin-horseradish peroxide (HRP) (1:2000; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for 35 min at RT and developed for 15 min at RT by the DAB Substrate Kit (Vector Laboratories) to obtain a brown staining product. The sections were finally counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red before dehydration and coverslipped using Entellan® Neu (Merck).

B cell and T cell quantification

An Eclipse E200 light microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) was used to assess B cell and T cell pathology in the cerebellar sections of the mice. The following categories of pathology were defined: B cell infiltrates (B cells: ≥ 10), B cell aggregates (B cells: ≥ 20; clustered), T cell infiltrates (T cells: ≥ 10; B cells: < 10) and T cell clusters (T cells: ≥ 20; clustered).

Chemokine receptor staining

To stain for chemokine receptors, tissue sections were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval was done as mentioned above. Slides were washed between every incubation step with TBS-T and sections were incubated in a humidified chamber. Subsequently, slides were blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBS-T for 1 h at RT. All primary and secondary antibodies were diluted in 0.1% BSA (Table 1). Incubation with anti-CCR5, anti-CXCR5 or anti-CXCR6 antibody was performed overnight at 4 °C. For CCR5 staining, the secondary antibody incubation and development were carried out as mentioned above for the CD3+ T cell staining with a slight modification. The sections were developed only for 10 min using the Vector BCIP/NBT Kit (Vector Laboratories). For CXCR5 and CXCR6 staining, the tissue was incubated with a Cy™3-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research Labs, West Grove, PA, USA) for 2 h at RT in the dark and a sequential double-staining was performed by incubating the sections with either an anti-B220, anti-CD3 or anti-F4/80 antibody overnight at 4 °C. Slides were incubated with a biotinylated anti-rat antibody for 2 h at RT followed by another incubation step with streptavidin conjugated to Cy™2 (1:200; Jackson Immuno Research Labs) for 45 min at RT in the dark. All sections were counterstained using the Fluoroshield mounting medium with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Abcam). A technical negative control was included for each staining where the slide was incubated with secondary antibody only (Additional file 1).

Immunofluorescent images were taken and scanning of the slides was done using a Leica DMi8 inverted microscope equipped with the Thunder Imaging software (Leica Camera Ag, Wetzlar, Germany).

Luminex chemokine and cytokine assay

A MAGPIX® Luminex (Luminex Corporation, Austin, TX, USA) platform was used for chemokine and cytokine quantification in the serum and CSF in collaboration with the research group of Molecular and Experimental Cardiology at the Translational Research Center (TRC), University Hospital Erlangen.

To analyze the chemokines and cytokines in paired CSF and serum samples, a combination of the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Chemokine Panel 31-Plex Kit and the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokines IL-21, IL-22 and IL-23 (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used and the experiments were conducted following the manufacturer's instructions. A Bio-Plex Pro Mouse TH17 cytokine standard (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc.) was included in addition to the cytokine standards provided in the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Chemokine Panel 31-Plex Kit. Prior to MAGPIX® measurement, each sample was centrifuged and diluted in dilution buffer (provided in the kit). Every serum sample was diluted 1:5 and the dilution range for CSF was between 1:14 and 1:22, dependent on the amount obtained from each mouse. While serum was measured in duplicates, this was not the case with every CSF samples due to the restricted volume. Wells with > 1 analyte that was not measurable were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, a co-efficient of variation (CV) value of above 20 and a bead count under 50 were considered as exclusion criteria.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (9.2.0). Gaussian distribution of every dataset was checked using the Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test) or unpaired t test was used for normally distributed data points and a Kruskal–Wallis (followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison test) or Mann–Whitney test was applied for measurements that did not follow normal distribution. The statistical tests used for each analysis are mentioned in the results section. For both parametric and nonparametric datasets, a significance level of 5% was chosen and accordingly the p values are displayed as follows: p < 0.05 (*); p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***).

Results

Variable cerebellar B cell and T cell pathology in MP4-immunized mice

To evaluate the extent of B cell and T cell infiltration, cerebella of 31 MP4-immunized mice were screened for B220+ B cells and CD3+ T cells during the chronic stage of the disease. The mean of the disease onset was 26.52 ± 2.29 days and mice were killed 66.13 ± 1.83 days after immunization. The mean of the EAE score of the mice was 0.98 ± 0.16. Vehicle mice (control group immunized with CFA and PBS without antigen) were killed 62.00 ± 0.00 days after immunization and did not show any symptoms. MP4-immunized mice were categorized into different groups based on the number of cerebellar B cell infiltrates and aggregates or T cell infiltrates and clusters during the chronic disease stage. Representative images of the four main categories (i.e., B cell infiltrates, T cell infiltrates, B cell aggregates and T cell clusters) are shown in Fig. 2. A detailed summary of the different groups based on the B cell and T cell pathology is listed in Table 2. Groups of mice with a minimum of n = 3 were used for further analysis. Therefore, groups showing the following criteria were excluded from the study: no B cell and T cell pathology, no B cell and moderate T cell pathology, high B cell and moderate T cell pathology. Furthermore, an additional comparison was done between groups of mice with more than 30 B cell aggregates in the cerebellar tissue and those with no B cell aggregates as shown in Table 3.

Differential expression of chemokines and cytokines in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice

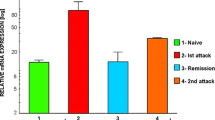

The levels of 34 cytokines and chemokines were quantified in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice that were categorized based on the extent of their cerebellar B cell and T cell pathology (Table 2). 18 of these cytokines and chemokines were elevated in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice compared to vehicle mice (Fig. 3).

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in the CSF comparing different groups of MP4-immunized mice. The comparison of the cytokine and chemokine concentration (pg/ml) in the “m B cell/m T cell”, the “m B cell/h T cell”, “h B cell/h T cell” groups and the controls is displayed. Only those chemokines and cytokines showing a significant difference in the concentration between the different groups are displayed. Mean values ± SEM are shown. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. One-way ANOVA (normal distribution), Kruskal–Wallis test (no normal distribution). CCL C-C motif chemokine ligand, CXCL C-X-C motif chemokine ligand, GM-CSF granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, h B cell/h T cell high B cell and T cell pathology, IL interleukin, IP10 interferon-γ-induced protein 10, m B cell/h T cell moderate B cell and high T cell pathology, m B cell/m T cell moderate B cell and T cell pathology, SEM standard error of the mean

The concentration of fractalkine and IL-2 was higher in CSF samples of the “moderate B cell and T cell pathology” (m B cell/m T cell) group compared to controls (p < 0.05), while CXCL16 was additionally significantly elevated in the “high B cell and T cell pathology” (h B cell/h T cell) group compared to controls (p < 0.05). Furthermore, CCL5, CCL7, CCL12, CCL19, CCL22, CXCL13 and IL-16 were significantly higher in the “h B cell/h T cell” group in comparison to vehicle mice (p < 0.05). In addition to CCL4, CXCL12, granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-22 and interferon-γ-induced protein 10 kDa (IP10), which were significantly elevated in the “moderate B cell and high T cell pathology” (m B cell/h T cell) group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01), CCL3 showed a significantly higher concentration in the “m B cell/h T cell” and the “h B cell/h T cell” compared to the control group (p < 0.05). Moreover, eotaxin was significantly elevated in all three pathological groups in comparison to controls (p < 0.05). In addition to a significantly increased level of CCL1 in the “m B cell/h T cell” and the “h B cell/h T cell” group compared to vehicle mice (p < 0.05, p < 0.001), this chemokine was also significantly upregulated in the “h B cell/h T cell” group compared to the “m B cell/m T cell” group (p < 0.05).

A specific chemokine signature is associated with B cell aggregation in MP4-immunized mice

CCL1, CCL5, CCL7, CCL12, CCL22 and CXCL13 were significantly higher in the group with more than 30 B cell aggregates compared to the group without any B cell aggregates (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4).

Cytokine and chemokine concentrations in the CSF comparing MP4-immunized mice with or without B cell aggregates. The graphs display the cytokine and chemokine concentrations (pg/ml) in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice showing B cell aggregates (> 30 B cells) compared to mice without aggregation. Chemokines and cytokines with significant differences between the two groups are presented. Mean values ± SEM are shown. *p < 0.05, unpaired t-test (normal distribution), Mann–Whitney test (no normal distribution), CCL C-C motif chemokine ligand, CXCL C-X-C motif chemokine ligand, SEM standard error of the mean

CXCL16 expression in the serum is associated with the absence of B cell aggregates in MP4-immunized mice

Although there were no significant differences in the serum concentration of most of the cytokines and chemokines tested between the different groups, CXCL16 was significantly elevated in the serum of MP4-immunized mice that did not display any B cell aggregates in the cerebellum compared to those with a high amount of B cell aggregates (p < 0.05) (Additional file 1).

Comparative values between groups, which did not reach the significance level in CSF or serum, are shown in Additional file 1.

CXCR5 and CXCR6 are preferentially expressed in the cerebellum of MP4-immunized mice with high B cell and T cell pathology

Cerebellar tissue of mice from the different groups was additionally screened for the expression pattern of three specific chemokine receptors whose corresponding chemokines were significantly upregulated in the CSF of MP4-immunized mice. These receptors were chosen based on their association with the formation and maintenance of ELS (Table 4) [14, 20, 21].

While cerebellar expression of CCR5 was observed independent of the extent of B cell and T cell pathology in MP4-immunized mice, the presence of CXCR5 was mostly restricted to areas of high T cell infiltration and was mostly detected in the “h B cell/h T cell" group as well as in mice with a high number of B cell aggregates (Table 5, Fig. 5, Fig. 6). The same groups also showed an expression of CXCR6 which was primarily restricted to areas containing B cell aggregates in spatial association with infiltrates or only T cell-dominated infiltrates (Fig. 6). Additionally, we identified F4/80+ macrophages to express CXCR6 in the cerebellar tissue (Fig. 7), while T cells and B cells could be excluded as a source for CXCR5.

Expression of the chemokine receptor CCR5 in cerebellar tissue of MP4-immunized mice. In addition to A high B cell and T cell pathology and B its corresponding CCR5 expression, C moderate B cell and T cell pathology, and the associated D CCR5 expression is shown. Scale bars represent 50 µm. CCR C-C motif chemokine receptor

Discussion

Analysis of CSF and serum samples plays an important role in investigating the development and progression of pathophysiological processes in different diseases. In the case of neuroinflammatory disorders like MS, changes in chemokine and cytokine concentration, especially in the CSF, can be correlated to disease progression and CNS pathology [7, 22].

Given the restrictions of obtaining paired CSF and tissue samples from MS patients containing ELS, in this study we used the MP4-induced EAE model to identify a specific chemokine/cytokine signature associated with B cell and T cell pathology, with a particular focus on B cell aggregates. To this end, paired CSF and serum levels of an array of different cytokines and chemokines were compared between different groups of MP4-immunized mice that were stratified according to their cerebellar pattern of B cell and T cell pathology. Our findings indicate that a range of molecules were significantly upregulated especially in the CSF of MP4-immunized compared to control mice.

For example, CSF levels of CXCL16 were significantly higher in two groups, the “m B cell/m T cell” group and the “h B cell/h T cell” group. The importance of this chemokine in the formation of ELS and T cell accumulation has been previously described [20, 23]. CXCL16 is highly expressed in the CNS during pathological conditions such as in MS [24] and its specific receptor CXCR6 is primarily expressed on T cells [25,26,27,28], but also on microglial cells [29]. We did not detect CXCR6+ T cells in the cerebellum of the MP4-immunized mice. In our model, F4/80+ macrophages were responsible for CXCR6 expression, which is similar to findings in patients with glioblastoma [29].

Moreover, fractalkine levels are known to be increased in the CSF of patients with clinically isolated syndrome and are believed to be involved in the recruitment of CX3CR1+ CD4+ T cells into the CNS in early stages of MS [30]. However, we found an increase in the concentration of fractalkine in the CSF of mice with “m B cell/ m T cell pathology” compared to controls in the chronic stage of MP4-immunized EAE. Therefore, an influence of this chemokine at a later stage of the disease is conceivable. One of the interesting candidates that was significantly elevated in all three pathological groups in comparison to controls was eotaxin. Eotaxins are known to facilitate eosinophil recruitment to sites of inflammation [31]. In the context of MS, an elevation of eotaxin-1 (CCL11) in the CSF and plasma was associated with disease progression and severity especially in patients with secondary progressive disease [32]. Which target cell population is responsive to this increase in eotaxin in the CSF in the MP4-induced EAE model and what role this chemokine plays remain to be clarified.

Another interesting candidate was CCL1, which was also the only chemokine whose expression levels significantly correlated with the extent of B cell and T cell pathology. One can assume a protective function of CCL1 in the MP4-induced EAE model, due to its involvement in the proliferation of regulatory T cells which are known to secrete anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 [33].

Additionally, the chemokines CCL1, CCL5, CCL7, CCL12, CCL22 and CXCL13 were associated with the presence of cerebellar B cell aggregates in MP4-immunized mice. The role of CXCL13 in the recruitment of B cells and follicular helper T cells has been extensively described for both MS and EAE [5, 7, 13, 14, 34,35,36,37]. Although these studies indicate a potential role of this chemokine in the formation of ELS by recruiting immune cells to the site of inflammation [10, 38], we did not detect any CXCR5 expression neither on B cells nor T cells in the cerebellum of MP4-immunized mice. In addition to CXCL13 it is conceivable that CCL5 may also be involved in the recruitment of immune cells into the CNS in MP4-immunized mice. EAE induced in CCR5-knockout mice showed a decrease in infiltrating immune cells indicating an important role of CCL5 in cell recruitment into the CNS [39]. Moreover, CCL5 is thought to be important for leukocyte extravasation, thus facilitating the migration of these cells into the CNS [40] and has also been described to be responsible for recruiting monocytes and memory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [41, 42]. Interestingly, CCL5 is associated with a chemokine profile which predicts the presence of ELS in colorectal cancer [21]. However, given that its receptor CCR5 was expressed in the cerebellar tissue independent of the presence of B cell aggregates, its function in MP4-induced EAE might not be restricted to ELS formation and maintenance. CCL7 is another candidate that is involved in the formation of ELS in a mouse model of atherosclerosis [43]. In EAE, blockade of CCL7 led to a decreased migration of leukocytes [44]. Next to CCL12, which has been described to be involved in EAE development [45], CCL22 has also been shown to play a role in EAE by recruiting T cells and macrophages [46,47,48]. Additionally, in breast cancer CCL22 is known to influence the recruitment of regulatory T cells to areas of immune cell infiltrates [49]. Regarding its role in the development of ELS, the level of CCL22 was shown to be elevated in ELS+ patients with an autoimmune disease of the thyroid gland [50].

In addition to the analysis of CSF, we also examined paired serum samples. Despite an elevated (pro)inflammatory profile in the CSF, as discussed above, we noticed minimal alterations in the cytokine and chemokine expression pattern in the serum of MP4-immunized mice compared to vehicle. This observation can be explained by the fact that the CNS/CSF compartment might be conducive for immune cell recruitment, proliferation and differentiation independent of the periphery in the chronic stage of the disease [14, 17]. Interestingly, the level of CXCL16 was significantly increased in the serum of mice without cerebellar B cell aggregates compared to those with aggregates. It can be speculated that mice with B cell aggregates fostered a more local and compartmentalized environment for the survival and differentiation of immune cells than mice without these aggregates. Therefore, inflammation might have been more trapped in mice with B cell aggregates without the need for immune cell trafficking from the periphery. However, precisely why CXCL16 was the only chemokine that was upregulated in the serum cannot be explained by our current findings.

Conclusion

There is a paucity of studies focusing on the molecular signature involved in ELS formation and maintenance in the CNS of mice due to the challenging nature of CSF collection. Our data provide a comprehensive overview of several chemokine and cytokine candidates that were upregulated in the CSF and may be involved in the development and maintenance of B cell aggregates. While future studies need to validate our findings using a higher number of mice, our current findings point towards a distinct profile of chemokines that can be used to predict cerebellar B cell aggregation in the chronic stage of MP4-induced EAE. Regarding the occurrence of ELS in MS patients, the identification of a specific chemokine signature in human CSF would be highly beneficial for ante mortem studies of these structures.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ARRIVAL:

-

Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments

- B6:

-

C57BL/6

- BAFF:

-

B-cell activating factor of the TNF family

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CCL:

-

C-C motif chemokine ligand

- CCR:

-

C-C motif chemokine receptor

- CFA:

-

Complete Freund´s adjuvant

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CO2 :

-

Carbon dioxide

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CV:

-

Coefficient of variation

- CXCL:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

- CXCR:

-

C-X-C motif chemokine receptor

- DAPI:

-

4',6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EAE:

-

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- ELS:

-

Ectopic lymphoid structures

- FAU:

-

Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg

- FDC:

-

Follicular dendritic cells

- FPZ:

-

Franz-Penzoldt Center

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- h B cell/h T cell:

-

High B cell and T cell pathology

- HRP:

-

Horseradish peroxidase

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IFN:

-

Interferon

- IFA:

-

Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant

- IP10:

-

Interferon-γ-induced protein 10 kDa

- LT:

-

Lymphotoxin

- m B cell/h T cell:

-

Moderate B cell and high T cell pathology

- m B cell/m T cell:

-

Moderate B cell and T cell pathology

- MS:

-

Multiple sclerosis

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PETZ:

-

Preclinical Experimental Center for Animals

- PFA:

-

Paraformaldehyde

- PO4 :

-

Phosphate

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- RRMS:

-

Relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis

- RT:

-

Room temperature

- SEM:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SLO:

-

Secondary lymphoid organs

- SPMS:

-

Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis

- TBS:

-

Tris-buffered saline

- TBS-T:

-

TBS + 0.1% Tween 20

- TNF:

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- TRC:

-

Translational Research Center

- WT:

-

Wild-type

References

Lassmann H, Bradl M. Multiple sclerosis: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133(2):223–44.

Cencioni MT, et al. B cells in multiple sclerosis—from targeted depletion to immune reconstitution therapies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(7):399–414.

Moccia M, et al. B cells in the CNS at postmortem are associated with worse outcome and cell types in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(1):e1108.

Machado-Santos J, et al. The compartmentalized inflammatory response in the multiple sclerosis brain is composed of tissue-resident CD8+ T lymphocytes and B cells. Brain. 2018;141(7):2066–82.

Magliozzi R, et al. Meningeal B-cell follicles in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis associate with early onset of disease and severe cortical pathology. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 4):1089–104.

Krumbholz M, et al. BAFF is produced by astrocytes and up-regulated in multiple sclerosis lesions and primary central nervous system lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2005;201(2):195–200.

Krumbholz M, et al. Chemokines in multiple sclerosis: CXCL12 and CXCL13 up-regulation is differentially linked to CNS immune cell recruitment. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 1):200–11.

Serafini B, et al. Detection of ectopic B-cell follicles with germinal centers in the meninges of patients with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2004;14(2):164–74.

Magliozzi R, et al. Inflammatory intrathecal profiles and cortical damage in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(4):739–55.

Mitsdoerffer M, Peters A. Tertiary lymphoid organs in central nervous system autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2016;7:451.

Peters A, et al. Th17 cells induce ectopic lymphoid follicles in central nervous system tissue inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35(6):986–96.

Pikor NB, et al. Integration of Th17- and lymphotoxin-derived signals initiates meningeal-resident stromal cell remodeling to propagate neuroinflammation. Immunity. 2015;43(6):1160–73.

Magliozzi R, et al. Intracerebral expression of CXCL13 and BAFF is accompanied by formation of lymphoid follicle-like structures in the meninges of mice with relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;148(1–2):11–23.

Batoulis H, et al. Central nervous system infiltrates are characterized by features of ongoing B cell-related immune activity in MP4-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Clin Immunol. 2015;158(1):47–58.

Gardner C, et al. Cortical grey matter demyelination can be induced by elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines in the subarachnoid space of MOG-immunized rats. Brain. 2013;136(Pt 12):3596–608.

Kuerten S, et al. MBP-PLP fusion protein-induced EAE in C57BL/6 mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2006;177(1–2):99–111.

Kuerten S, et al. Tertiary lymphoid organ development coincides with determinant spreading of the myelin-specific T cell response. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124(6):861–73.

Šakić B. Cerebrospinal fluid collection in laboratory mice: literature review and modified cisternal puncture method. J Neurosci Methods. 2019;311:402–7.

Tacke S, et al. Effects of a fully humanized Type II anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody on peripheral and CNS B cells in a transgenic mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(6):3172.

Zhang X, et al. Identification of key genes and pathways contributing to artery tertiary lymphoid organ development in advanced mouse atherosclerosis. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19(4):3071–86.

Coppola D, et al. Unique ectopic lymph node-like structures present in human primary colorectal carcinoma are identified by immune gene array profiling. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(1):37–45.

Ragheb S, et al. Multiple sclerosis: BAFF and CXCL13 in cerebrospinal fluid. Mult Scler. 2011;17(7):819–29.

Nanki T, et al. Pathogenic role of the CXCL16-CXCR6 pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(10):3004–14.

Rosen SF, et al. Single-cell RNA transcriptome analysis of CNS immune cells reveals CXCL16/CXCR6 as maintenance factors for tissue-resident T cells that drive synapse elimination. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):108.

Fukumoto N, et al. Critical roles of CXC chemokine ligand 16/scavenger receptor that binds phosphatidylserine and oxidized lipoprotein in the pathogenesis of both acute and adoptive transfer experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2004;173(3):1620–7.

Kim JV, et al. Two-photon laser scanning microscopy imaging of intact spinal cord and cerebral cortex reveals requirement for CXCR6 and neuroinflammation in immune cell infiltration of cortical injury sites. J Immunol Methods. 2010;352(1–2):89–100.

Hou L, Yuki K. CCR6 and CXCR6 identify the Th17 cells with cytotoxicity in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Front Immunol. 2022;13: 819224.

Hsiao CC, et al. White matter lesions in multiple sclerosis are enriched for CD20(dim) CD8(+) tissue-resident memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51(2):483–6.

Lepore F, et al. CXCL16/CXCR6 axis drives microglia/macrophages Phenotype in physiological conditions and plays a crucial role in glioma. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2750.

Blauth K, et al. The role of fractalkine (CX3CL1) in regulation of CD4(+) cell migration to the central nervous system in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2015;157(2):121–32.

Huber AK, et al. An emerging role for eotaxins in neurodegenerative disease. Clin Immunol. 2018;189:29–33.

Huang J, et al. Inflammation-related plasma and CSF biomarkers for multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(23):12952–60.

Barsheshet Y, et al. CCR8(+)FOXp3(+) T(reg) cells as master drivers of immune regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(23):6086–91.

Gunn MD, et al. A B-cell-homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt’s lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391(6669):799–803.

Legler DF, et al. B cell-attracting chemokine 1, a human CXC chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues, selectively attracts B lymphocytes via BLR1/CXCR5. J Exp Med. 1998;187(4):655–60.

Breitfeld D, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1545–52.

Kim CH, et al. Subspecialization of CXCR5+ T cells: B helper activity is focused in a germinal center-localized subset of CXCR5+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;193(12):1373–81.

Zhan J, et al. Ectopic lymphoid follicles in progressive multiple sclerosis: From patients to animal models. Immunology. 2021;164(3):450–66.

Gu SM, et al. CCR5 knockout suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 mice. Oncotarget. 2016;7(13):15382–93.

dos Santos AC, et al. CCL2 and CCL5 mediate leukocyte adhesion in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis–an intravital microscopy study. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;162(1–2):122–9.

Schall TJ, et al. Selective attraction of monocytes and T lymphocytes of the memory phenotype by cytokine RANTES. Nature. 1990;347(6294):669–71.

Volin MV, et al. RANTES expression and contribution to monocyte chemotaxis in arthritis. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1998;89(1):44–53.

Lötzer K, et al. Mouse aorta smooth muscle cells differentiate into lymphoid tissue organizer-like cells on combined tumor necrosis factor receptor-1/lymphotoxin beta-receptor NF-kappaB signaling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(3):395–402.

Zhang Y, et al. miR-23b suppresses leukocyte migration and pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by targeting CCL7. Mol Ther. 2018;26(2):582–92.

Jiang Z, Jiang JX, Zhang GX. Macrophages: a double-edged sword in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunol Lett. 2014;160(1):17–22.

Forde EA, Dogan RN, Karpus WJ. CCR4 contributes to the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by regulating inflammatory macrophage function. J Neuroimmunol. 2011;236(1–2):17–26.

Dogan RN, et al. CCL22 regulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by controlling inflammatory macrophage accumulation and effector function. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(1):93–104.

Columba-Cabezas S, et al. Induction of macrophage-derived chemokine/CCL22 expression in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and cultured microglia: implications for disease regulation. J Neuroimmunol. 2002;130(1–2):10–21.

Gobert M, et al. Regulatory T cells recruited through CCL22/CCR4 are selectively activated in lymphoid infiltrates surrounding primary breast tumors and lead to an adverse clinical outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69(5):2000–9.

Armengol MP, et al. Chemokines determine local lymphoneogenesis and a reduction of circulating CXCR4+ T and CCR7 B and T lymphocytes in thyroid autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 2003;170(12):6320–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Stephanie Link, Anita Hecht and Heike Kloos for excellent technical support. We would also like to thank Winfried Neuhuber for sharing his expertise of CSF collection and the preparation of the cisterna magna and Krista DiSano for sharing her experience with MAGPIX® assays.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This study was supported by intramural funding of Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS participated in the study design, established and conducted experiments, interpreted and analyzed the data and drafted and wrote the manuscript. RC participated in study design, assisted with experiments, drafted and revised the manuscript for intellectual content, BD established and performed MAGPIX® measurements and analysis. ST participated in the study design and assisted with experiments, SK designed and supervised the study, immunized the mice and drafted and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for this study was given by the Regierung von Unterfranken (55.2-2531.01-91/14).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1.

Chemokine receptor staining and corresponding negative controls. Representative images of A a negative control using only secondary antibody only and its corresponding B CCR5 staining is displayed. Furthermore, the C negative control for D CXCR5 and E CXCR6 staining is shown. Scale bars represent 50 µm. CCR C-C motif chemokine receptor, CXCR C-X-C motif chemokine receptor, DAPI 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Fig. S2. CXCL16 concentration in the serum comparing MP4-immunized mice with or without B cell aggregates. The significant increase in the CXCL16 concentration (pg/ml) in the serum of MP4-immunized mice without B cell aggregates compared to mice showing B cell aggregates (> 30 B cells) is displayed. Mean values ± SEM are shown. *p < 0.05, unpaired t-test, CXCL C-X-C motif chemokine ligand, SEM standard error of the mean. Table S1. Non-significant data of cytokines and chemokines in the CSF of different pathology groups. Table S2. Non-significant data of cytokines and chemokines in the CSF with reference to B cell aggregates. Table S3. Non-significant data of cytokines and chemokines in the serum of different pathology groups. Table S4. Non-significant data of cytokines and chemokines in the serum with reference to B cell aggregates.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Schropp, V., Chunder, R., Dietel, B. et al. The presence of cerebellar B cell aggregates is associated with a specific chemokine profile in the cerebrospinal fluid in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroinflammation 20, 18 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02695-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-023-02695-z