Abstract

Background

Panniculitis, a type of inflammation of subcutaneous fat, is a relatively uncommon condition that usually presents as inflammatory nodules or plaques, with various proposed etiologic factors. The association between panniculitis and enthesitis-related arthritis has not been described previously.

Case presentation

Herein, we describe a case of a 11-year-old girl who presented with recurrent fever and painful subcutaneous nodules on her extremities and buttocks. Histological examination of the skin biopsy specimen revealed lobular panniculitis. Despite the use of prednisone and mycophenolate mofetil for several months, the patient experienced a relapse of skin lesions and additional symptoms of peripheral joint swelling and inflammatory lumbar pain. She was diagnosed with enthesitis-related arthritis after confirmation by imaging. The panniculitis demonstrated a sustained response when a tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor was used for enthesitis-related arthritis. At 2-year follow-up, her skin lesions and arthritis remained stable.

Conclusions

Although rare, panniculitis can be considered an unusual extra-articular manifestation of enthesitis-related arthritis based on clinical and pathological insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Panniculitis is a type of inflammation of subcutaneous fat, and is a relatively uncommon condition that usually presents as inflammatory nodules or plaques, often accompanied by episodic fever, chills, and myalgia. It can be related to infections (streptococcal infection or tuberculosis), external insults (traumatic or cold panniculitis), malignancy, or connective tissue diseases (CTD), such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and dermatomyositis (DM).

Enthesitis-related arthritis (ERA) is a type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) that belongs to the spectrum of diseases in juvenile spondyloarthropathy. Although ERA is characterized by a greater frequency of extra-articular manifestations in children, including uveitis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), than in adults with spondyloarthropathy [1], the association of skin lesions and ERA has not previously been described. Herein, we report the first case of ERA-associated panniculitis, which may provide clinical and pathological insights.

Case presentation

A 11-year-old girl presented with recurrent fever and erythema for 2 months. Her medical history included episodes of fever, accompanied by painful subcutaneous nodules on her extremities and buttocks. The patient initially responded well to treatment with dexamethasone (5 mg, intramuscular injection) instead of antibiotics; however, she experienced symptomatic relapse approximately 2 weeks later. Physical examination revealed multiple tender erythematous nodules in the upper and lower extremities (Fig. 1A, B). Physical examination results were otherwise unremarkable.

Complete blood count (CBC) showed normal levels of hemoglobin and platelets, with slightly elevated leukocytes (13.01 × 109/L with 87.5% neutrophils). High acute phase reactants, C-reactive protein (CRP) (32.7-105 mg/L; normal < 10 mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (36-53 mm/h; normal < 20 mm/h), were observed.

A detailed clinical assessment was performed to identify the risk factors for panniculitis, including anti-streptolysin O (ASO), T-SPOT.TB, tuberculin purified protein derivative test, blood culture, antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), extractable nuclear antigen, perinuclear and cytoplasmic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (p-ANCA and c-ANCA), antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus anticoagulant, serum levels of C3 and C4, and alpha 1-antitrypsin were detected, and all were negative or within the normal range. Abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed no abnormalities.

Histopathological examination of the skin biopsy specimen obtained from a representative nodule revealed lobular panniculitis with moderate infiltration of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Fig. 2A). No evidence of vasculitis, necrosis, or infection caused by bacteria, fungi, or mycobacteria was observed in the biopsy specimen. Based on the present case report and a combination of serological tests and histopathological examination, we diagnosed the patient with panniculitis.

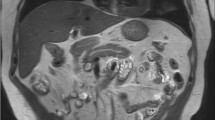

The patient received prednisone (1.5 mg/kg/day) combined with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) (300 mg/m2/dose) as glucocorticoid-sparing therapy which showed obvious improvement. However, with prednisone tapered to 10 mg/day for approximately 10 months, the girl suffered again from high fever and tenderness nodular, along with new symptoms: her left ankle and foot became swollen and there was point tenderness on the dorsal side of the talonavicular joint. Her medical history revealed no history of acute anterior uveitis or IBD. Laboratory examination results, including those for ASO, human leukocyte antigen 27 (HLA-B*27), rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, and ANA, were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left foot showed that the tarsal area involvement with bone marrow edema in the cuboid and cuneiform bones (Fig. 3A, B), indicating enthesitis. A second skin biopsy revealed a small aggregation of lymphocytes and histiocytes in the fat lobules (Fig. 2B). Therefore, prednisone treatment was increased to 15 mg/day, and ibuprofen (7.5 mg/kg/dose) was prescribed as well. However, the patient had recurrent episodes of painful erythema and swelling in her left foot, with gradual low back pain 1 year before admission. CT of the sacroiliac joint (SIJ) revealed sacroiliitis with bone destruction (Fig. 3C) and the hip MRI showed inflammation in the fat layer (Fig. 3D).

Finally, the patient was diagnosed with panniculitis and ERA, with the latter diagnosed based on the International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification criteria for JIA 2001 [2]. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF-α) antibody infliximab (IFX) (5 mg/kg at 2-week intervals initially, repeated in monthly intervals three times, currently at 8-week intervals) plus methotrexate (15 mg/m2) was chosen as therapy, whereas prednisone and MMF were gradually discontinued. She experienced an improvement in both joints and panniculitis (Fig. 4A, B). Laboratory tests showed that CBC and serum acute phase reactants returned to the normal range. Furthermore, CT revealed no further progression of bone destruction in the SIJ (Fig. 5A), and inflammation of the fat layer on the buttocks was significantly reduced (Fig. 5B). At 2-year follow-up, her skin lesions and arthritis remained stable.

Discussion

Panniculitis is an uncommon condition with a multifactorial etiology. It can be a skin complication of various autoimmune diseases, including SLE, DM and vasculitis [3]. However, few studies have reported panniculitis with arthritis.

In this case, the patient presented with recurrent painful erythema, verified by histopathological examination as lobular panniculitis. On histological examination, the predominance of lymphocytes and histiocytes, rather than neutrophilic cells, indicated that neutrophilic lobular panniculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and Crohn's disease could be largely ruled out. Additionally, the absence of vasculitis excluded the possibility of nodular vasculitis (Bazin disease) and some infectious panniculitis, such as leprosy nodular erythema. Considering the patient’s clinical features, including age, medical history, marked inflammatory state with high fever, and elevated inflammatory markers, lobular panniculitis associated with systemic disease was strongly suspected, including SLE, JDM, pancreatic disease, and potentially some neoplastic diseases.

Skin lesions are considered idiopathic or a cutaneous manifestation of an unknown systemic disease without positive findings at that time. However, we could not wait until the "clinical picture" was fully displayed; therefore, glucocorticoid was prescribed and tapered with careful attention. Meanwhile, we repeatedly screened for underlying systemic diseases until the presence of arthritis and ERA was confirmed by imaging.

Regarding disease progression, panniculitis with high inflammation precedes the development of overt arthritis, and it was poorly controlled with glucocorticoid tapering, which also could not effectively prevent progression of arthritis. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient with panniculitis with late-onset ERA. The patient reported considerable relief of joint and back pain with anti-TNF-α therapy, and no fever or skin manifestation recurrence was observed at the 2-year follow-up. Hence, the association between panniculitis and ERA has been discussed here from the perspective of disease development and therapy.

ERA is a specific category of JIA that is characterized by axial or peripheral arthritis and enthesitis. Different extra-articular manifestations can encompass the clinical spectrum. These include severe muscular atrophy, growth failure, pubertal delay, ophthalmological complications, IBD, and psoriasis [4]. Although rare, SAPHO (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteomyelitis) syndrome [5], secondary renal amyloidosis [4, 6], and cardiac involvement, such as aortitis [7] have also been reported in ERA. However, skin disorders have been seldom reported, and no cases of panniculitis have been previously reported.

On the other hand, in most cases, panniculitis presents with episodes of joint pain and swelling due to acute inflammatory effusion; however, imaging-confirmed persistent arthritis is uncommon [8]. Few cases of panniculitis and arthritis have been reported worldwide. Of these, panniculitis occurs together with arthritis in some patients to form a triad of pancreatitis, panniculitis, and polyarthritis, referred to in the literature as PPP syndrome [9], which is associated with acute and chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic malignancies. Owing to the presence of pancreatic disease, panniculitis, and arthritis were considered secondary to fat necrosis. Two other cases reported mycobacterium-associated lobular panniculitis that mimicked a rheumatoid nodule in RA [10] and a panniculitis with RA without obvious infection [11]. However, unlike these studies, our patient showed no evidence of pancreatic involvement or pathogenic infection. Therefore, we believe that panniculitis with late-onset ERA is a unique condition.

Studies on possible mechanisms underlying this association have also been reported. In 2015, Dennis McGonagle et al. proposed a concept of "MHC-I-opathy," including Behçet disease and several clinically distinct spondyloarthropathies—all associated with MHC-I alleles, such as HLA-B*51, HLA-B*27, HLA-C*0602, or epistatic endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1(ERAP1) interaction [12]. These disorders share key features of disease localization to physical stress sites, either at barrier surfaces (oral mucosa, gut, and skin) or internal sites (joints and entheses, including interfaces between mobile structures in the eye, vessel walls, and valves). An abnormal response to normal levels of stress or a normal response to abnormal levels of stress occurring at barrier surfaces or sites of microdamage collectively lead to the priming of innate immunity. That was just like we observed the association between IBD and its extra-intestinal manifestations, which involve the mouth, skin (barrier surfaces), and joints, eyes (interfaces between mobile structures). Therefore, immunologically, spondyloarthropathies such as ERA and skin abnormality panniculitis may share a common immunopathogenetic basis. Based on the perspective of monism, ERA with panniculitis may involve different presentations of "MHC-I-opathy".

Another evidence that verifies the entity of ERA with panniculitis is the high efficacy of anti-TNF-α therapy. IFX has been used to treat orbital lobular panniculitis [13] and other inflammatory dermatoses [14] with satisfactory results. TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine released by many cell types, including monocytes, macrophages and lymphocytes, which are major cells contributing to panniculitis. High-affinity receptors of TNF-α were also expressed in adipose tissue [15]. Therefore, treating panniculitis with anti-TNF-α agents that are equally effective for ERA is reasonable. And our patient experienced a clear and sustained benefit from this approach.

Paradoxically, TNF-α blockade can lead to psoriasis and erythema nodosum because of a dysregulated type I interferon response [16]. Specifically, anti-TNF treatment prolongs type I interferon production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells by inhibiting their maturation. As this patient received TNF-α antagonist therapy, this should be seriously considered. The skin lesions in this patient require further investigation.

Conclusions

From clinical and pathological insights, although rare, skin lesions, such as panniculitis, should be considered as possible extra-articular manifestations when ERA is defined. Furthermore, this indicates that many skin lesions, although not specific, require further investigation to identify a possible underlying inflammatory rheumatic disease, and unusual extra-articular manifestations of arthritis can respond positively to proper treatment and management.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANA:

-

Antinuclear antibody

- ASO:

-

Anti-streptolysin O

- anti-dsDNA:

-

Anti-double-strand DNA

- anti-CCP:

-

Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide

- anti-TNF-α:

-

Anti-tumor necrosis factor TNF alpha

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computerized tomography

- CTD:

-

Connective tissue disease

- c-ANCA:

-

Cytoplasmatic anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- DM:

-

Dermatomyositis

- ENA:

-

Extractable nuclear antigen

- ERA:

-

Enthesitis-related arthritis

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- ERAP1:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1

- HLA-B*27:

-

Human leukocyte antigen 27

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- IFX:

-

Infliximab

- JIA:

-

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

- MMF:

-

Mycophenolate mofetil

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MTX:

-

Methotrexate

- pDCs:

-

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells

- PPD:

-

Purified protein derivative

- p-ANCA:

-

Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- RF:

-

Rheumatoid factor

- SAPHO:

-

Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteomyelitis

- SLE:

-

Systemic lupus erythematosus

- SIJ:

-

Sacroiliac joint

References

Hanene LF, Ammar LB, Maatallah K, Nessib DB, Triki W, Kaffel D, et al. Enthesitis-related arthritis and spondylarthritis: the same disease or disparate entities? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18(1):93–9.

Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–2.

Rangel LK, Villa-Ruiz C, Lo K, Cobos G, Sicco KL, Vleugels RA, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Lupus Erythematosus Panniculitis/Profundus: A Retrospective Review of 61 Patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(11):1264–6.

Sarma PK, Misra R, Aggarwal A. Outcome in patients with enthesitis related arthritis (ERA): juvenile arthritis damage index (JADI) and functional status. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:18.

Pagnini I, Scavone M, Maccora I, Mastrolia MV, Marrani E, Bertini F, et al. The Development of Extra-Articular Manifestations in Children With Enthesitis-Related Arthritis: Natural Course or Different Disease Entity? Front Med. 2021;8: 667305.

Packham JC, Hall MA. Long-term follow-up of 246 adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: functional outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41(12):1428–35.

Tangcheewinsirikul S, Sukharomana M, Charuvanij S. Disability and disease-related damage in Thai children and adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2023;21(1):68.

Zheng W, Song W, Wu Q, Yin Q, Pan C, Pan H. Analysis of the clinical characteristics of thirteen patients with Weber-Christian panniculitis. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(12):3635–41.

Kim EJ, Park MS, Son HG, Oh WS, Moon KW, Park JM, et al. Pancreatitis, Panniculitis, and Polyarthritis Syndrome Simulating Cellulitis and Gouty Arthritis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2019;74(3):175–82.

Chen W-S, Lee Y-F, Wang H-P, Su K-Y, Lee C-H, Huang D-F. Mycobacterium-associated lobular panniculitis, mimicking a rheumatoid nodule in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Formos Med Assoc. 2009;108(8):673–6.

Fragoulis GE, Stamopoulos P, Barbatis C, Tzioufas AG. Panniculitis: an unusual presenting manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016;34(1):126–8.

McGonagle D, Aydin SZ, Gul A, Mahr A, Direskeneli H. ’MHC-I-opathy’-unified concept for spondyloarthritis and Behcet disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015;11(12):731–40.

Mavrikakis I, Georgiadis T, Fragiadaki K, Sfikakis PP. Orbital lobular panniculitis in Weber-Christian disease: sustained response to anti-TNF treatment and review of the literature. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55(6):584–9.

Drosou A, Kirsner RS, Welsh E, Sullivan TP, Kerdel FA. Use of infliximab, an anti-tumor necrosis alpha antibody, for inflammatory dermatoses. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7(5):382–6.

Beutler BA, Milsark IW, Cerami A. Cachectin/tumor necrosis factor: production, distribution, and metabolic fate in vivo. J Immunol. 1985;135(6):3972–7.

Conrad C, Di Domizio J, Mylonas A, Belkhodja C, Demaria O, Navarini AA, et al. TNF blockade induces a dysregulated type I interferon response without autoimmunity in paradoxical psoriasis. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):25.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient and her family.

Funding

This work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China [2021YFC2702005] and Beijing Hospitals Authority's Ascent Plan [DFL20221001].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WXM: Conceptualization, Writing- Original draft preparation. FS: Writing- Reviewing and Editing. TXH: Investigation. HWM: Conceptualization, Supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee of Beijing Children's Hospital has approved the publication and saved the informed consent application of this case report.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient's parents.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, W., Sun, F., Han, T. et al. Panniculitis with late onset enthesitis-related arthritis: a case report. Pediatr Rheumatol 21, 97 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00888-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12969-023-00888-7