Abstract

Background

Artificial intelligence can assist in cardiac image interpretation. Here, we achieved a substantial reduction in time required to read a cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) study to estimate left atrial volume without compromising accuracy or reliability. Rather than deploying a fully automatic black-box, we propose to incorporate the automated LA volumetry into a human-centric interactive image-analysis process.

Methods and results

Atri-U, an automated data analysis pipeline for long-axis cardiac cine images, computes the atrial volume by: (i) detecting the end-systolic frame, (ii) outlining the endocardial borders of the LA, (iii) localizing the mitral annular hinge points and constructing the longitudinal atrial diameters, equivalent to the usual workup done by clinicians. In every step human interaction is possible, such that the results provided by the algorithm can be accepted, corrected, or re-done from scratch. Atri-U was trained and evaluated retrospectively on a sample of 300 patients and then applied to a consecutive clinical sample of 150 patients with various heart conditions. The agreement of the indexed LA volume between Atri-U and two experts was similar to the inter-rater agreement between clinicians (average overestimation of 0.8 mL/m2 with upper and lower limits of agreement of − 7.5 and 5.8 mL/m2, respectively). An expert cardiologist blinded to the origin of the annotations rated the outputs produced by Atri-U as acceptable in 97% of cases for step (i), 94% for step (ii) and 95% for step (iii), which was slightly lower than the acceptance rate of the outputs produced by a human expert radiologist in the same cases (92%, 100% and 100%, respectively). The assistance of Atri-U lead to an expected reduction in reading time of 66%—from 105 to 34 s, in our in-house clinical setting.

Conclusions

Our proposal enables automated calculation of the maximum LA volume approaching human accuracy and precision. The optional user interaction is possible at each processing step. As such, the assisted process sped up the routine CMR workflow by providing accurate, precise, and validated measurement results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Left atrial (LA) enlargement is frequently associated with atrial fibrillation, thromboembolic events and eventually death [1, 2]. Even in the absence of atrial fibrillation, the abnormal shape or size of the LA has been linked to stroke, heart failure and major adverse cardiac events [3].

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is the reference imaging modality for measuring cardiac chamber volumes, including the LA [4]. LA dilatation is best recognized by measuring the maximum LA volume (\({LAV}_{max}\)) at ventricular end-systole.Footnote 1 It is usually measured using two long-axis (LAx) multiphase cine images, the two chamber- and four chamber- (2ch- and 4ch-, respectively) views. This analysis is known as the biplane area‐length method and has been validated for routine CMR assessment both in sinus rhythm and in atrial fibrillation [5]. It comprises the following steps: (i) identifying the frame of end-systolic (ES) phase, (ii) outlining the LA in the two views and (iii) drawing longitudinal atrial diameters. When using dedicated software, a human expert performs these steps manually in a few minutes. However, this time adds to the total time required for the evaluation and reporting of a whole-heart CMR study, which typically takes 30 min or more. An alternative method of calculating the LA volume from multislice cine stacks offers additional options for quantification of phasic function and strain but is even more time consuming [6].

We aimed at reducing the time required to compute \({LAV}_{max}\) without loss of reliability, by assisting the human expert in the CMR assessment. For this purpose, we developed Atri-U, an image analysis pipeline that reproduces above-mentioned steps (i)–(iii) of the biplane area-length method. Atri-U was then integrated into an established clinical workup that provides the human expert a way to review and revise the outputs in a familiar interface. As final outcomes, we evaluate the frequency and severity of disagreements between Atri-U and an expert and the resulting gain in time by checking, accepting, and eventually processing only cases that are rated with insufficient quality.

Methods

Datasets

LAx cines from 1697 patients, admitted to our institution between June 2010 and June 2019 for whole-heart clinical routine CMR imaging, formed the initial sample of the study. Exclusion criteria and age limits (≥ 18 years) were applied and 1379 cases remained, from which \(N=300\) pairs of 2ch- and 4ch-view cines were selected for the training and evaluation of Atri-U (samples A, B and C for training, validation and testing, respectively, see Table 1). The exclusion criteria, the selection process (adapted from [7]) and acquisition parameters are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1 and Figure S1. Additionally, \(N=150\) consecutively acquired CMR studies starting July 2019 were used for assessment of the time saving achieved with Atri-U (samples D1/D2). The reference standard was created, as previously described [8], by a radiologist (TAD) and a radiologist in training (CA) for samples A, B and C and by a senior radiologist subspecialized in cardiovascular imaging with 6 years of experience (GS) for sample D1 (for details see Additional file 1: Section E2). Demographic and clinical characteristics were extracted from radiological reports and are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S2 and Figure S2. Finally, in order to extend the field of application to 3D data of the LA, multislice axial stacks of CMR cines were also analyzed (\(N=65\)). Full details of the 3D segmentation task, as well as an intra-subject correlation of 2D and 3D volumetry, are provided in the Additional file 1: Section E3). The study was approved by the Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz ethics committee (project-ID 2019-01637).

Evaluation of Atri-U in clinical setting

In its clinical application, Atri-U generates proposals for all steps of the biplane area-length method, as described in “Atri-U modules that implement the biplane area-length method” section, which are then made available to the human expert for review and optional correction. The added value of Atri-U was measured by the average time saving per case. For this evaluation, Atri-U processed \(N=150\) consecutively acquired cases (sample D2), the chronologically first \(N=50\) of which had been also processed by a senior radiologist (GS, sample D1), resulting in \(N=200\) annotations (see Table 1). A cardiologist with 7 years of experience in cardiac imaging (PH), who was not involved in the creation of the reference standard and was not told that 50 of the LAx cine pairs appeared twice, scored all annotations in randomized order. He used a categorical rating, scoring the quality of each module separately (ES frame detection; segmentation of LA; diameter placement). The given score was based on the estimated time required to obtain an acceptable result as follows: Score 0: 100 percent time saving (no correction needed); Score 1: 50 percent time saving (minor correction needed); Score 2: no time saving (major correction needed). Expected time saving was computed with the assumption that the better the proposed annotation by Atri-U was, the more time could be saved. The total expected time saved minus the actual time required for the scoring yielded an estimate of the time saving for a given cine pair. Additionally, the \({LAVI}_{max}\) was compared in the subset of 50 cases that appeared in both samples D1 and D2 (processed by the radiologist and Atri-U, respectively), focusing on the correlation and the difference in cases that did receive a score other than 2.

Atri-U modules that implement the biplane area-length method

Overview

Atri-U was implemented with fully convolutional neural networks followed by conventional morphometric and geometrical computations to mimic the steps performed by humans as detailed in the following paragraphs. In the scope of the proof of concept, we kept a single model.

Module 1 that implements detection of ES frame

The mitral valve states were classified on each 4Ch-view frame using a fine-tuned fully convolutional neural network [9] with the closed states as the positive and the open states as the negative class. The number of channels in the four convolutional layers were 64, 128, 256, and 512, respectively. The binary classification was optimized via stochastic gradient decent with momentum using cross-entropy loss with closed states as the positive and the open states as the negative label (for more details on the network architectures see Additional file 1: Section E2). Upon prediction, the last frame of the largest block of closed states was defined as the ES frame and the performance metrics of accuracy, recall and precision were computed for each CMR study.

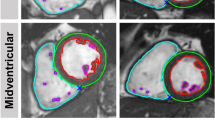

Module 2 that implements segmentation of left atrium

Pixel-wise automated segmentation of the LA in both the 2Ch- and 4Ch-view was performed with the U-Net [10, 11]. The overlap of two LA segmentations was quantitatively evaluated using established performance metrics (for details see Additional file 1: Table S3 and [12]).

Module 3 that implements placement of longitudinal atrial diameters

Localization of the mitral annular hinge point pairs on both LAx views (referred as mitral landmarks throughout the text) [13] was trained with the same neural network architecture as in module 2. Two comparison metrics were calculated between two independent ratings (specifically, radiologist vs. radiologist or radiologist vs. Atri-U): the sum of the Euclidean distances of the mitral landmarks (in mm) and the deviating angle of the mitral annular level (in degrees, for an example see Additional file 1: Figure S3). Upon prediction and in combination with the segmentations from module 2, the longitudinal diameters were automatically placed as the line starting at the mid-point of the mitral annular level (level connecting the two respective mitral landmarks) and passing through the center of mass of the left atrial segmentation [14] (see Fig. 1).

Automated calculation of the left atrial (LA) volume from long-axis CMR cines and 3D cines with Atri-U. The existing workflow enables the manual review of automated predictions at each individual step of the biplane area-length method (orange column). If revision is required the corrected predictions are used to recalculate maximum LA volume (LAVmax, where A2ch and A4ch are LA areas and L is the minimum of two longitudinal diameters). For the 3D cines, the steps of frame detection and landmark localization do not apply as the volume is calculated from the sum of atrial area on each slice times the slice thickness (see Additional file 1: Section E3). ES = end-systole, CMR = cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Computation of \({LAVI}_{max}\)

Each of the above modules was evaluated separately by descriptive statistics, between the two radiologists and between each radiologist and Atri-U. Additionally, maximum LA volume index (\({LAVI}_{max}\), in mL/m2 body surface area) was calculated with the biplane area-length method from the combination of atrial areas and diameters at the detected ES frames (without further modification) and compared between \({LAVI}_{max}^{h}\) and \({LAVI}_{max}^{a}\) and between \({LAVI}_{max}^{h}\) and \({LAVI}_{max}^{Atri-U}\) with Bland–Altman analyses in R (v 3.4.1, blandr package, v 0.5.1) [15], where:

- \({LAVI}_{max}^{h}\):

-

human segmentations and human ES frame selection.

- \({LAVI}_{max}^{a}\):

-

automated segmentations at predefined (human) ES frame.

- \(LAVI_{\max }^{Atri - U}\):

-

automated segmentations at automatically detected ES frame. Note that the ES frame does not necessarily coincide with the visually selected frame.

We estimated the 95% confidence interval from the inter-rater comparisons (sample B) and assessed what percentage of differences in volumes estimated by Atri-U and radiologists for sample C were outside the established confidence bounds for \({LAVI}_{max}^{a}\) and \(LAVI_{\max }^{Atri - U}\).

Results

Evaluation of Atri-U in clinical setting

Of the 200 input cines pairs, the cardiologist deemed three as of insufficient image quality for the intended analysis, all belonging to sample D2, while in one case the same cine pair was also represented in the D1 sample but was there rated as having sufficient quality. According to his scoring, no or minimal correction was required (i) for module 1, in 142 out of 147 cases from Atri-U (97%) and 46 out of 50 (92%) from the radiologist, (ii) for module 2 in 138 out of 147 (94%) from Atri-U and 50 out of 50 from the radiologist (100%) and (iii) for module 3 in 139 out of 147 (95%, mostly overlapping with interdependent module 2) and 50 out of 50 from the radiologist (100%) (Fig. 2a). While the failure cases for Atri-U could be readily identified, the rest of the cases provided a good correlation between manual and automated LA volume estimation (Fig. 2b).

Results from reading of the consecutive clinical sample (samples D1 and D2). a Representation of score received per case, processing step, and processing type (senior radiologist and Atri-U, 50 and 150 annotations respectively). The legends are listed at the bottom of the panel. The corresponding proportions are listed in Table 2. b Scatter plot of volumes obtained by the senior radiologist (sample D1) and Atri-U (sample D2) for the 50 cases that appeared in both samples, along with their histograms. The color coding corresponds to the highest scores given by the senior cardiologist during the rating of the time-saving potential, where Score 0: 100 percent time saving (no correction needed); Score 1: 50 percent time saving (minor correction needed); and Score 2: no time saving (major correction needed). For example, for the four datapoints with the red rim at the bottom of the graph, he scored the outputs of Atri-U as requiring a correction “from scratch”, while for two of them he independently scored the outputs of the senior radiologist as requiring minor correction (yellow center). The majority of cases were scored as requiring no or minor correction and their LAVImax correlate well between human and Atri-U. LAVImax = maximum left atrial volume index

Based on above failure rates and the time to perform the quality assessment and corrections, we estimated the expected average time saving. On average, manual processing of the LA in two views at ES frame would require 5 s for the frame detection, 40 s for segmentation (for 2ch- and 4ch-view, respectively) and 10 s for placement of mitral landmarks/longitudinal diameters (for 2Ch- and 4Ch-view, respectively), in total 105 s. The average time required by the cardiologist for reading the proposed annotations was in average 24.9 and 23.0 s (for samples D1 and D2, respectively). Thus, the average time required for the complete assessment of the LA using Atri-U was 33.9 s (see Table 2). This resulted in a time saving of approximately 71 s per dataset processed by Atri-U, which corresponds to a 68 percent reduction compared to the fully manual procedure.

Evaluation of Atri-U modules

In module 1, the median accuracy was 0.96 (Additional file 1: Figure S4 and Table S4). In module 2, the automated LA segmentations had a high overlap of median Dice coefficient of 0.96 and 0.94 with the first radiologist and 0.96 and 0.94 with the second radiologist, for 2Ch- and 4Ch-views respectively (see also Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S5). An overview of the distributions of absolute LA area in the included samples and the inter-rater variability is listed in Additional file 1: Table S6 and S7, respectively. In module 3, median of the sum of distance deviations between radiologist and Atri-U for the mitral landmarks was from 4.3 to 6.3 mm, corresponding to a median deviation of 1 to 2.5 pixels per hinge point. Atri-U and the radiologists had angle deviations of the mitral annular levels in the same range as inter-rater variability (Additional file 1: Table S8). The resulting lengths of the longitudinal diameters from the combination of LA area segmentations and mitral landmarks are listed in Additional file 1: Table S9. Apart from the variant used by default (i.e. passing through the center of mass of the atrial area), the longitudinal diameters constructed as the longest perpendicular line from the mitral annular level to the posterior wall of the atrium are also listed there.

Performance evaluation of segmentation. Boxplots of Dice coefficients and maximum Hausdorff-distance (in mm) values for left atrium area segmentation at end-systole in the validation (sample B) and test (sample C) subsets. In blue radiologist1 vs. segmentation algorithm, in orange radiologist2 vs. segmentation algorithm and in green radiologist1 vs. radiologist2. Latter comparison was performed for sample B. The higher variability for sample B compared to C can be explained on the one hand by the difference in sampling type (B mostly included cardiac diseased subjects, while C was random) and on the other hand by the age of the exams: B was selected from older retrospective studies with heterogenous acquisition parameters, while C was selected from a more homogeneous sample acquired within a year. LAx = long-axis

\({LAVI}_{max}\) at predefined and at detected ES frame

At the visually selected ES frame, the \({LAVI}_{max}^{a}\) values computed from modules 2 and 3 were for all 50 cases of sample C within the previously defined confidence bounds. In the Bland–Altman analyses, there was a slight average underestimation of 0.6 mL/m2 (upper and lower limits of agreement of − 4.9 and 6.0, respectively) compared to the calculation based on human segmentations (\({LAVI}_{max}^{h}\)). In the complete version, where the ES frame was additionally selected automatically \(\left( {LAVI_{\max }^{Atri - U} } \right)\), 47 of 50 cases were within the previously defined confidence bounds (94%), with a slight average overestimation of 0.8 mL/m2 (upper and lower limits of agreement − 7.5 and 5.8, respectively) (see also Fig. 4 and Additional file 1: Figures S5, S6 and Table S10). The accuracy of volume prediction was independent of LA size. Susceptibility of LA volume to time frame selection is shown in Additional file 1: Figure S7.

Left atrial volume distributions for combinations of manual and automated steps for segmentation and end-systolic (ES) frame selection. Estimated distribution of maximum LAVI in sample C calculated middle: from human raters, left: by automated segmentation on the same time-frame as for the human rating (LA volumes did not substantially deviate from human) and right: by automated segmentation after additional prediction of the end-systolic (ES) frame (Atri-U). With Atri-U, 47 cases showed values within the acceptable limits, while 3 cases deviated more (marked as triangles, circles and stars across all three methods). In general, the lower and upper boundaries of the violin plot represent minimum and maximum values, respectively. The distribution of the underlying data (scatter) is represented by the curved sides of the plot

Availability of Atri-U

At our institution, Atri-U is implemented in the clinical routine, as previously described [16]. For each qualifying CMR study, Atri-U is automatically triggered and it takes approximately 120 s until the automatically calculated \({LAV}_{max}\) and \({LAVI}_{max}\) is available.Footnote 2 Since Atri-U is not a certified medical product, the segmentations, longitudinal diameters and the predicted ES frame are reviewed for potential errors and, after manual revision by the expert, the volumetric values get updated accordingly (see video in Additional file 2). A stand-alone backend version of Atri-U is available on a public repository.

Discussion

We developed an automated image-analysis pipeline for the computation of \({LAV}_{max}\) analysis from LAx CMR cines and integrated it into an established clinical workflow. The expected average time gain when checking and applying minor corrections instead of annotating from ground-up was substantial. In the exemplary clinical setting, the cardiologist required only one third of the time of the original process for reading automatically generated proposals, while retaining the reliability and accuracy that is required in clinical practice. The cardiologist identified the highest need for manual interaction in the segmentations of atrial areas (six percent of Atri-U segmentations), which was the most time-consuming step of the analysis and a strong contributor to the overall time-saving effect of Atri-U. The required correction rates for de novo ES frame selection and placement of longitudinal diameters based on mitral landmarks were three and five percent, respectively.

Each step of the biplane area-length method, traditionally being performed by the human expert, was implemented as a fully convolutional neural network module and in general reached human-level performance with sporadic failure cases. Atri-U is the first assessment of an automated \({LAV}_{max}\) estimation from CMR cines, meeting the requirements for clinical use as presented in the introduction. Atri-U is also filling the gap of fully automated processing of bulk datasets for research, as it can be used, retrained, and even adapted and extended independently of the user interface, unlike commercially available tools.

Fully convolutional neural network segmentation was recently introduced for LAx views of the LA in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [17]. In contrast to this rather homogenous population, the presented algorithms were trained on and evaluated with heterogenous samples consisting of routine CMR cines originating from patients with a variety of heart diseases, including atrial fibrillation. Irrespective of the size of the LA, Dice coefficients of around 0.95 were obtained, similar to a study with almost 4000 training cases [12]. Narrower limits of agreement have been previously published for LA segmentation [18], yet on healthy subjects, while in our samples—extracted from the hospital database—all grades of atrial dilatation were represented [19]. Unlike segmentation, the detection of the relevant ES frame and the mitral landmarks are two mostly unexplored [13] but essential steps in order to further automate LA volume estimation with the biplane area-length method. We measured the LA longitudinal diameter and by extension the estimated LA volume in two ways, as either the line passing through the center of mass or as the longest perpendicular line passing through the mitral annulus [14]. This option for comparison of the two approaches shows the flexibility of our clinically embedded software development platform, where different calculation methods or even a manual editing of the diameter can be readily implemented on top of Atri-U.

We did not only evaluate the performance of single steps of the pipeline (ES frame detection, segmentation of the LA in each cine view, localization of the mitral landmarks), but also the combination thereof. Due to the propagation of variance from one step to the other, we observed larger deviations from human ground-truth when the automated detection of the ES frame was added to the process. Although in three out of 50 cases this resulted in a predicted \({LAV}_{max}\) outside the previously defined confidence bounds (sample C), the variability in ES frame selection was also observed between the two experts (sample D1).

While the focus of our study was on 2D LAx CMR, obtaining the volume directly from the segmentation of the LA in multislice stacks is of potential clinical interest [20]. With the same fully convolutional neural networks model as for LAx cines, but adapted to incorporate context along the third dimension, we could show human-level performance in the segmentation of the LA in 3D cines for all phases of the cardiac cycle, in cases with atrial fibrillation and/or LA enlargement, showing a strong correlation with 2D volumetry (see Additional file 1: Sections E3, E4 and video in Additional file 3). In such an application, the time gain may be even higher than for 2D image analysis. Both the 3D and the 2D quantifications could also be useful to assess longitudinal changes in LA volumetry.

Out of the recently suggested nine key considerations for study design in artificial intelligence image analysis [21], six items were fulfilled and three were not: as a limitation, we did not include a fully independent external test subset (consideration 2) and did not include multi-vendor image acquisitions (consideration 3). Multiple devices, sequences and magnetic field strengths were used, despite acquisition with equipment of the same manufacturer. The third consideration that was not fulfilled is to demonstrate the way the algorithm makes the decision (consideration 8). Continuous application of Atri-U will inform about the potential of the method and possibly reveal failure cases that can be addressed by relatively trivial re-training of the model. The six key considerations that our study fulfilled include: the split of the sample into training, validation, and test subsamples (consideration 1) of appropriate size (consideration 4). Atri-U was trained using manual annotation (consideration 5) and the performance of Atri-U was compared to that of radiology experts (consideration 7), albeit not with a statistical test. By publishing code and models (consideration 9) that operate on the raw images (consideration 6), we facilitate objective comparison with alternative methods and evaluation on other (external) datasets. Because of the considerations that were not met, we cannot conclude about the generalizability of the method with the pretrained models in any other case than our local. Additionally, it assumes that placement of the LAx cines is in conformity with the current guidelines [4], since slice positioning might impact the accuracy of LA volume quantification and lead to differences in volume estimation from exam to exam. Finally, the design of the study did not allow testing for non-inferiority of the proposed method. However, the intended application is integrated in a pipeline in which experts validate every single processing step and systematic failure in a new setting would be readily recognizable.

Conclusions

We have developed, evaluated, and deployed a process for automated calculation of \({LAV}_{max}\) from LAx CMR cines that offers an average time saving for evaluation of clinical CMR exams of more than a minute per case (66% reduction). The integration into an existing clinical workflow provides options for review and revision of individual steps, ensuring that the expert retains control over the process and the clinical end-point. As the LAx cines are part of a whole-heart CMR protocol, their automated segmentation, including the calculation of \({LAV}_{max}\), further contributes to the comprehensive analysis of all four heart chambers. The broad availability of automated segmentation and volumetry will greatly facilitate the analysis of quantitative parameters of the LA in clinical settings as well as in research studies of cardiac diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The imaging datasets underlying this article are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of participants. However, software code generated during this study, a stand-alone backend version of Atri-U with trained models, and a sample dataset will be made available on a public repository: https://git.upd.unibe.ch/openscience/atri-u; Operating system: Platform independent; Programming languages: Python, Matlab; Required packages: NiftyNet; License: GNU General Public License v3.0.

Notes

All references to the time point of the cardiac cycle are made with respect to the ventricular cardiac phase.

This is the time that passes from the acquisition until the results are available to the radiologist. The time needed by the fully convolutional neural networks for the image analysis is less than five seconds. The rest of the time is consumed by data transfer over the network and format conversions. The body surface area is calculated from the image file-header fields for subject’s weight and height.

Abbreviations

- CMR:

-

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- ES:

-

End-systolic

- LA:

-

Left atrium/left atrial

- LAV max :

-

Maximum left atrial volume

- LAVI max :

-

Maximum left atrial volume index

- LAx:

-

Long axis

- 2Ch:

-

Two-chamber view

- 4Ch:

-

Four-chamber view

References

Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Bailey KR, Leibson CL, Montgomery SC, Takemoto Y, et al. Left atrial volume: important risk marker of incident atrial fibrillation in 1655 older men and women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:467–75. https://doi.org/10.4065/76.5.467.

Khan MA, Yang EY, Zhan Y, Judd RM, Chan W, Nabi F, et al. Association of left atrial volume index and all-cause mortality in patients referred for routine cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2019;21:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-018-0517-0.

Froehlich L, Meyre P, Aeschbacher S, Blum S, Djokic D, Kuehne M, et al. Left atrial dimension and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with and without atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart. 2019;105:1884–91. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315174.

Schulz-Menger J, Bluemke DA, Bremerich J, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG, et al. Standardized image interpretation and post-processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance—2020 update: Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (SCMR): Board of Trustees Task Force on Standardized Post-Processing. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2020;22:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00610-6.

Sievers B, Kirchberg S, Addo M, Bakan A, Brandts B, Trappe H-J. Assessment of left atrial volumes in sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation using the biplane area-length method and cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging with TrueFISP. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6:855–63. https://doi.org/10.1081/jcmr-200036170.

Evin M, Cluzel P, Lamy J, Rosenbaum D, Kusmia S, Defrance C, et al. Assessment of left atrial function by MRI myocardial feature tracking. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:379–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.24851.

Bernard O, Lalande A, Zotti C, Cervenansky F, Yang X, Heng P-A, et al. Deep learning techniques for automatic MRI cardiac multi-structures segmentation and diagnosis: is the problem solved? IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2018;37:2514–25. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2018.2837502.

Hudsmith LE, Petersen SE, Francis JM, Robson MD, Neubauer S. Normal human left and right ventricular and left atrial dimensions using steady state free precession magnetic resonance imaging. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2005;7:775–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10976640500295516.

He K, Zhang X, Ren S, Sun J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In: 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2016. p. 770–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90.

Çiçek Ö, Abdulkadir A, Lienkamp SS, Brox T, Ronneberger O. 3D U-Net: learning dense volumetric segmentation from sparse annotation. In: Ourselin S, Joskowicz L, Sabuncu M, Unal G, Wells W. (editors) Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention – MICCAI 2016. MICCAI 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 9901. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46723-8_49.

Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In: Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells W, Frangi A. (editors) Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention – MICCAI 2015. MICCAI 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 9351. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28

Bai W, Sinclair M, Tarroni G, Oktay O, Rajchl M, Vaillant G, et al. Automated cardiovascular magnetic resonance image analysis with fully convolutional networks. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2018;20:65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-018-0471-x.

Tarroni G, Oktay O, Bai W, Schuh A, Suzuki H, Passerat-Palmbach J, et al. Learning-based quality control for cardiac MR images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2019;38:1127–38. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2018.2878509.

Rodevand O, Bjornerheim R, Ljosland M, Maehle J, Smith HJ, Ihlen H. Left atrial volumes assessed by three- and two-dimensional echocardiography compared to MRI estimates. Int J Cardiac Imaging. 1999;15:397–410. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006276513186.

Datta D. Blandr. 2017. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.824514. Accessed 27 Nov 2020.

Anastasopoulos C, Weikert T, Yang S, Abdulkadir A, Schmülling L, Bühler C, et al. Development and clinical implementation of tailored image analysis tools for COVID-19 in the midst of the pandemic: the synergetic effect of an open, clinically embedded software development platform and machine learning. Eur J Radiol. 2020;131: 109233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2020.109233.

Vigneault DM, Xie W, Ho CY, Bluemke DA, Noble JA. Ω-Net (Omega-Net): fully automatic, multi-view cardiac MR detection, orientation, and segmentation with deep neural networks. Med Image Anal. 2018;48:95–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2018.05.008.

Petersen SE, Aung N, Sanghvi MM, Zemrak F, Fung K, Paiva JM, et al. Reference ranges for cardiac structure and function using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) in Caucasians from the UK Biobank population cohort. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2017;19:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-017-0327-9.

Petersen SE, Khanji MY, Plein S, Lancellotti P, Bucciarelli-Ducci C. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging expert consensus paper: a comprehensive review of cardiovascular magnetic resonance normal values of cardiac chamber size and aortic root in adults and recommendations for grading severity. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:1321–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jez232.

Pop M, Sermesant M, Zhao J, Li S, McLeod K, Young A, et al. Statistical atlases and computational models of the heart. In: Atrial segmentation and LV quantification challenges: proceedings of STACOM 2018. Berlin: Springer; 2018.

Bluemke DA, Moy L, Bredella MA, Ertl-Wagner BB, Fowler KJ, Goh VJ, et al. Assessing radiology research on artificial intelligence: a brief guide for authors, reviewers, and readers-from the radiology editorial board. Radiology. 2019;294:487–9. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019192515.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Claudia Rutigliano, Timo van Alst and Professor Michael Kuehne for their contribution and valuable input.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for the research reported in this article. The article processing costs were covered by the “publication fund for open access” of the University of Basel.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CA: conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, writing, original draft preparation, reviewing and editing draft. SY: methodology, software, validation. MP: data curation, validation, reviewing and editing draft. TAD: data curation, validation, reviewing and editing draft. SK: data curation, validation. JC: software, investigation. MR: methodology, software. EK: methodology, software. RA: statistical analysis. PH: scoring, validation. BS: reviewing and editing draft. AWS: reviewing and editing draft. JB: supervision and reviewing draft. GS: conceptualization, supervision, data curation, reviewing and editing draft. AA: methodology, software, supervision, writing, reviewing and editing original draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (EKNZ) ethics committee (project-ID 2019-01637), which waived the requirement of written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Contains descriptions of the studied populations, complementary results on segmentation and mitral valve classification, as well as detailed description of methods used for training and evaluation of the algorithms. Finally, a 3D cine segmentation algorithm is presented in detail.

Additional file 2. A video recording of the implementation of Atri-U in the clinical workflow established at our institution. Please note that Atri-U is not a certified medical product.

Additional file 3. An exemplary result is depicted on a 3D stack video recording. 3D cine segmentation of the left atrium (LA) at three distinct phases of the cardiac cycle: end-systole (left), end-diastole (middle) and directly preceding atrial contraction (right). The manual segmentation is shown in red and the automated segmentation in blue.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Anastasopoulos, C., Yang, S., Pradella, M. et al. Atri-U: assisted image analysis in routine cardiovascular magnetic resonance volumetry of the left atrium. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 23, 133 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-021-00791-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-021-00791-8