Abstract

Background

Myocardial fibrosis occurs in end-stage heart failure secondary to mitral regurgitation (MR), but it is not known whether this is present before onset of symptoms or myocardial dysfunction. This study aimed to characterise myocardial fibrosis in chronic severe primary MR on histology, compare this to tissue characterisation on cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging, and investigate associations with symptoms, left ventricular (LV) function, and exercise capacity.

Methods

Patients with class I or IIa indications for surgery underwent CMR and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. LV biopsies were taken at surgery and the extent of fibrosis was quantified on histology using collagen volume fraction (CVFmean) compared to autopsy controls without cardiac pathology.

Results

120 consecutive patients (64 ± 13 years; 71% male) were recruited; 105 patients underwent MV repair while 15 chose conservative management. LV biopsies were obtained in 86 patients (234 biopsy samples in total). MR patients had more fibrosis compared to 8 autopsy controls (median: 14.6% [interquartile range 7.4–20.3] vs. 3.3% [2.6–6.1], P < 0.001); this difference persisted in the asymptomatic patients (CVFmean 13.6% [6.3–18.8], P < 0.001), but severity of fibrosis was not significantly higher in NYHA II-III symptomatic MR (CVFmean 15.7% [9.9–23.1] (P = 0.083). Fibrosis was patchy across biopsy sites (intraclass correlation 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.39, P = 0.001). No significant relationships were identified between CVFmean and CMR tissue characterisation [native T1, extracellular volume (ECV) or late gadolinium enhancement] or measures of LV function [LV ejection fraction (LVEF), global longitudinal strain (GLS)]. Although the range of ECV was small (27.3 ± 3.2%), ECV correlated with multiple measures of LV function (LVEF: Rho = − 0.22, P = 0.029, GLS: Rho = 0.29, P = 0.003), as well as NTproBNP (Rho = 0.54, P < 0.001) and exercise capacity (%PredVO2max: R = − 0.22, P = 0.030).

Conclusions

Patients with chronic primary MR have increased fibrosis before the onset of symptoms. Due to the patchy nature of fibrosis, CMR derived ECV may be a better marker of global myocardial status.

Clinical trial registration Mitral FINDER study; Clinical Trials NCT02355418, Registered 4 February 2015, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02355418

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic primary mitral regurgitation (MR) exposes the left ventricle (LV) to a volume overload, with progressive remodelling, left ventricular (LV) dilatation, and myocardial dysfunction. Despite long-standing guidelines on the indications for surgery in symptomatic and asymptomatic severe chronic primary MR, one fifth of patients continue to present post-operatively with reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF) and an increased risk of later heart failure [1]. Although there is support for early repair in asymptomatic patients at low risk of complications, there are limited randomised data to separate early repair from watchful waiting. Given the ageing of the population, the proportion of older patients with asymptomatic severe chronic primary MR is growing and these patients do not always find the option even of low risk surgery attractive in the absence of symptomatic benefit. Current class I indications for surgery in asymptomatic individuals require confirmation of severe MR, LV cavity dilatation (end systolic dimension ≥ 4.0 cm) and LVEF ≤ 60%, yet intervention based on these cut-offs is associated with a 50% reduction in long-term survival and 2.5 fold increase in risk of heart failure [2]. Given the limitations of these parameters in the management of primary MR, there is a need for additional information to support either watchful waiting or early surgery [3].

Early autopsy studies in patients with chronic severe primary MR demonstrated a stepwise increase in myocardial fibre hypertrophy and interstitial space with increasing symptoms and LV dysfunction [4]. However, these changes were only found to be significant in those who died with advanced heart failure; meanwhile, animal studies have suggested that progressive development of supra-normal levels of myocardial fibrosis with exhaustion of muscle hypertrophy mechanisms is responsible for the onset of heart failure in MR [5]. While histological data in humans are limited, there has been rapid growth in studies using cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging to characterise LV remodelling and myocardial architecture in primary MR. Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) has been identified in a significant proportion of patients with chronic severe primary MR before surgery and is thought to reflect focal replacement fibrosis [6, 7]. In previous studies, we and others have demonstrated elevated myocardial T1 relaxation times and expansion of the extracellular volume fraction (ECV), an imaging biomarker of diffuse interstitial fibrosis (DIF), in asymptomatic primary MR [6, 8]. However, histological data in asymptomatic primary MR are lacking, and there are no data linking fibrosis on histology with either T1, ECV, LGE or functional change in the LV. Our hypothesis is that volume overload in severe MR is associated with fibrosis that can be measured by CMR tissue characterisation, and that fibrosis is associated with symptom status, impaired global longitudinal strain and reduced exercise capacity. Therefore, the aims of this prospective study of patients with chronic severe primary MR were to assess: (i) the histological changes within the myocardium; (ii) the association between histological extent of fibrosis and tissue characterisation on CMR; (iii) the relationship between extent of myocardial fibrosis (histology; CMR) on LV function, and exercise capacity.

Methods

Study cohort

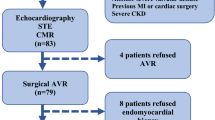

All patients were enrolled in the prospective multicentre Mitral FINDER study from three tertiary cardiothoracic centres with high volume mitral valve repair programmes (patients undergoing surgery at: Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham n = 52, Coventry Hospital n = 49, New Cross Hospital n = 3; clinicaltrials.gov NCT02355418) between August 2015 and March 2018. Full study inclusion and exclusion criteria have been reported [9], with patients referred for mitral valve surgery based on European Society of Cardiology class I or class IIa indications [10]. In brief, consecutive adult patients aged over 18 years were included, based on the presence of severe primary degenerative MR, diagnosed and quantified on echocardiography according to standard guidelines [11]. Patients were excluded if they had primary MR not due to degenerative disease, secondary MR, congenital heart disease, inherited or acquired cardiomyopathy, a history of myocardial infarction, symptomatic concomitant coronary artery disease, moderate or severe aortic valve disease, pregnancy, or could not undergo either CMR or cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET).

All patients underwent clinical assessment with history and examination, blood sampling [including full blood count, haematocrit, renal function, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NTproBNP)], symptom assessment with New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and multiparametric CMR at the primary study site (Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham).

Classification into fibroelastic deficiency (FED) versus Barlow’s disease was based on independent review of echocardiographic and CMR imaging by two experienced imaging cardiologists (RPS, NCE), and confirmed on surgery.

The study received favourable ethical review from the UK National Research Ethics Service (15/EM/0243) and conformed to the Helsinki Declaration. Subjects gave written consent to participate.

Histology

During mitral valve surgery, three LV biopsies were obtained from each patient from the LV septum, anterior and posterior free wall, using a 14G TruCut needle or scalpel. Histological analyses were performed blinded to clinical and imaging data (DN, BL). Myocardial connective tissue was analysed on ×20 scanned Masson Trichrome sections (Axio Scan.Z1 ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) which stains extracellular connective tissue blue and stains muscle purple-red. Fibrosis burden quantified as collagen volume fraction (CVF) was derived from Ilastik machine-learning based, supervised object classification and segmentation software [12], which was trained in-house against an expert (DN). This system identified and quantified the surface area of connective tissue versus the surface area of muscle. CVFmean represents the mean average of CVF values from the three biopsies originating from an individual patient, and CVFmax represents the highest CVF across the three sites for the individual patient, or from all available sites in those where it was not possible to collect all three biopsies.

Control myocardial samples from single whole-heart autopsy sections were obtained from autopsies of eight subjects (five males, all Caucasian, mean age 59 ± 6.9 years). These data allowed comparison of age-related histological changes in subjects who died of non-cardiac causes with no evidence of macroscopic or microscopic cardiac lesions.

Measurement of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was performed by manually quantifying the cross-sectional area (CSA) of 50 randomly selected cardiomyocytes via ZEN software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy). To ensure consistency, only cardiomyocytes found in its mid-axial orientation (denoted by presence of central nuclei) were eligible for quantification.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

LV and right ventricular (RV) volumes and mass, and left atrial volumes were acquired in line with 1.5T CMR scanner (Avanto; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) protocols [13, 14]. Single breath hold modified Look-Locker inversion recovery sequence (MOLLI) was used for T1 mapping in the LV base and mid-ventricular short axis levels before and between 15 and 20 min after contrast administration (3, 3, 5 scheme), according to previously published parameters [8]. LGE imaging was performed 7 to 10 min after 0.15 mmol/kg of gadolinium based-contrast agent (Gadovist Bayer Healthcare, Berlin, Germany).

CMR imaging analyses were performed offline using Cvi42® (version 5.3.6, Circle Cardiovascular Imaging, Calgary, Canada) by an operator (BL) blinded to all demographic and descriptive data, and without information regarding any clinical parameters. For ventricular volume analysis, the endocardial border was detected with thresholding, delineation of atria/ventricles was confirmed in matched long axis planes, and papillary muscles and trabeculations were included in ventricular mass. For T1 mapping, two short axis maps (base and mid LV) were manually contoured for endo- and epicardial borders. Partial voluming of blood was minimised by using a 20% offset from the endo- and epicardial border [15]. ECV values stated in the manuscript are global values. Blood was taken for measurement of haematocrit at the same time as the CMR scans. Additional region-of-interest (ROI) ECV values were obtained from the mid LV septum, anterior free wall and posterior free wall, to mirror the origins of histological biopsy collection. Myocardial deformation on CMR was quantified using feature tracking of cine images with Cvi42®, as per previously described methodology [16, 17]. LGE mass was quantified automatically using a signal intensity thresholding of > 3 standard deviations above reference mean [18].

Symptom status and exercise testing

Symptom status was assessed using the NYHA classification status, as assessed by the responsible clinician, with NYHA I classified as asymptomatic and NYHA II–IV as symptomatic. Objective testing of exercise capacity was carried out using maximal exertion treadmill CPET, with incremental ramp protocols as per American Thoracic Society guidelines [19].

Statistical analyses

The baseline demographics of the cohort were summarized, with continuous variables reported as means ± standard deviations (SDs) where normally distributed, and as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) otherwise. Comparisons of continuous variables between groups were performed using independent samples t-tests for normally distributed variables, or Mann–Whitney U tests otherwise, with chi2-tests used to analyze nominal variables. Associations between continuous variables were assessed using Spearman’s (rho) or Pearson’s (R) correlation coefficients. Where applicable, these associations were further quantified using linear regression models. The goodness of fit of these regression models was assessed graphically, with logarithmic transformations applied where either poor fit or heteroscedasticity were identified. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 24, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, International Business Machines, Inc., Armonk, New York, USA), and P < 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant throughout.

Results

In total, 120 consecutive patients with severe primary degenerative MR were recruited, of whom 105 were referred for mitral valve repair. One patient referred for surgery was subsequently excluded due to a requirement for percutaneous coronary intervention, leaving n = 104 for analysis, of whom 39 were referred for a class I indication (symptoms) and 65 were referred for a class IIa indication (high likelihood of repair). Only one patient required MV replacement. As expected given the indications for surgery, most of the cohort were asymptomatic, with 63% (n = 65) New York Heart Association (NYHA) class 1, 30% (n = 31) NYHA class II, and 8% (n = 8) NYHA class III. Demographic, histology and imaging data are summarised in Table 1. All 15 patients that declined surgery were asymptomatic with a class IIa indication for repair, but chose to be treated conservatively. Patients choosing conservative management were significantly older with lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), but had smaller LV end-systolic volume index (LVESVI) and less MR (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Histology of myocardial biopsies in severe chronic primary MR

Of the 104 patients undergoing MV repair, 234 biopsies were collected from 86 patients. Biopsies were taken from all three LV sites (septum, anterior and posterior free wall) in n = 67, with n = 14 having two biopsies, and n = 5 a single biopsy. Biopsies were not feasible across all biopsy sites due to limited visualisation or safe instrument access to the ventricular myocardium from the left atrial incision at the time of surgery. In addition, two patients chose to undergo surgery at institutions external to the study sites, where biopsies were not taken.

Myocardial fibrosis

MR patients had a median CVFmean of 14.6% [IQR 7.4–20.3] and CVFmax of 22.2% [10.2–31.8], which were significantly higher than control CVF values (3.3% [2.6–6.1], P < 0.001). The difference in fibrosis persisted when limited to asymptomatic MR patients compared to controls (CVFmean 13.6% [6.3–18.8], P < 0.001). Although there was a trend towards increased fibrosis in symptomatic patients compared to asymptomatic MR patients based on NYHA classification, this was not significant (CVFmean 15.7% [9.9–23.1] (P = 0.083) (Fig. 1; results remain non-significant when taking biopsy location and exclusion/inclusion of endocardium into account, Additional file 1: Table S3). There were no gender-related differences in fibrosis (CVFmean male 14.1% [7.3–18.5] vs. female 16.1% [11.4–24.6], P = 0.163).

Boxplots illustrating the distribution of mean collagen volume fraction (CVFmean) (top) and cardiomyocyte cross sectional area (CSA) (bottom) in autopsy controls vs. asymptomatic and symptomatic mitral regurgitation (MR) patients. P values are derived from Mann–Whitney U tests for non-parametric variables (collagen volume fraction) and independent T-test for parametric variables (cardiomyocyte cross sectional area, extracellular volume). MR mitral regurgitation

A total of 124 myocardial biopsies contained endocardium (median thickness 100 µm [58–181]), and 111 biospies contained only myocardium. Biopsies with endocardium showed higher CVF than those without endocardium (16.7% [10.4–27.1] vs. 6.6% [3.5–12.3], P < 0.001). There was a significant correlation between mean endocardial thickness and CVF (rho = 0.35, P < 0.001), consistent with endocardial thickening and subendocardial scar. The pattern of fibrosis varied between MR patients and within the myocardium, including diffuse interstitial fibrosis, perivascular fibrosis and areas of replacement fibrosis (Fig. 2).

Histological specimens from mitral regurgitation patients and controls. Sections are stained with Masson Trichrome highlighting fibrous tissue as blue and myocytes as purple-red. Histological fibrosis is patchy with little congruence in fibrosis burden across different biopsy sites. Extracellular volume fraction (ECV) can provide an overall estimation of myocardial status, but fails to account for endocardial fibrosis

There was no clear pattern to the distribution of myocardial fibrosis within each individual biopsy sample; although CVF in samples with endocardium was approximately twice that of mid-myocardial samples, no clear endocardial–epicardial gradient could be seen within the myocardium of each biopsy sample. In the 67 patients who had three biopsies, this heterogeneity was reflected in a low intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for fibrosis across the three biopsy sites (ICC = 0.23, 95% CI 0.08–0.39, P = 0.001).

Cellular hypertrophy

Direct histological quantification of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was performed via haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides. MR patients were found to possess marked cardiomyocyte hypertrophy compared to controls (CSA 853 ± 230 µm2 vs 124 ± 26 µm2, P < 0.001, Fig. 1) with histological quantification correlating significantly with CMR derived LV mass indexed (LVMI; R = 0.36, P = 0.001). There was a trend for cardiomyocyte CSA in symptomatic patients to be lower than asymptomatic patients (799 ± 218 µm2 vs 891 ± 232 µm2, P = 0.069).

Fatty infiltration

During examination of surgical biopsies, fat infiltration between cardiomyocytes was noted. As a potential confounder to T1 and ECV measurements (T2 mapping was not performed), fat infiltration was semi-quantitatively assessed by an experienced cardiac histopathologist blinded to clinical and imaging data using a scale of 0 (no fat infiltration) to 3 (prominent fat infiltration). Of 79 biopsies assessed, 52 (66%) contained no fat infiltration, 15 (19%) mild; 10 (13%) moderate; and 2 (3%) prominent fat infiltration (Fig. 2). Although extent of fat infiltration increased significantly with CVFmean (rho = 0.23, P = 0.045), there were no signficiant correlations with CMR parameters, including native T1 or ECV. There was however, a near-significant correlation with age (rho = 0.22, P = 0.056).

Histology and CMR measurement of myocardial fibrosis

The extent of histological fibrosis quantified on biopsy by CVFmean did not correlate significantly with either with native T1 (rho = 0.04, P = 0.714), or ECV (rho = 0.18, P = 0.101) regardless of whether analyses were performed according to global values (Fig. 3a) or according to region of interest drawn to match biopsy site (Additional file 2: Figure S1). However, a statistically significant association between CVFmean and ECV was present when eliminating endocardium from any analysis and limiting histological quantification to myocardium only (n = 56, rho = 0.33, P = 0.015; Fig. 3b). Conversely, no association was present between ECV and CVFmean quantified from biopsies containing endocardium (n = 64, rho = 0.03, P = 0.822).

Relationship between ECV and histological evidence of interstitial fibrosis on biopsy (CVFmean) for a all biopsies, and b biopsies containing only myocardium. The trendlines are based on regression models, with ECV as the independent variable, and Log2CVFmean as the independent variable. This relationship was not found to be statistically significant when all biopsies were included within analyses (a, Rho = 0.18, P = 0.101, N = 83), but became statistically significant when limiting analyses to biopsies that contained only myocardium (b, Rho = 0.33, P = 0.015, N = 56)

LGE was present in 34 (33%) of 102 patients who received gadolinium-based contrast agent, with a median mass of 0.98 g (IQR 0.33–2.47). Mid-myocardial LGE was located in the basal inferolateral LV segment (n = 23), and/or in the papillary muscles (n = 8), basal anterolateral segment (n = 3), mid inferolateral segment (n = 2) and mid septum (n = 1). The extent of histological fibrosis quantified on biopsy by CVFmean was not significantly correlated with the amount of left ventricular LGE (rho = − 0.09, P = 0.402).

Myocardial fibrosis, LV function and exercise capacity

The extent of histological fibrosis quantified on biopsy by CVFmean was not significantly correlated with CMR measured LV volumes, LVEF or LV mass, and there was no relationship with other imaging markers of LV function, including GLS and E/eʹ. There was however, a signficant positive correlation between CVFmean and NTproBNP (Rho = 0.35, P = 0.001) (Table 2). Sub-analysis using CVFmean derived from biopsy samples without endocardium did not result in any alterations in statistical significance (data not shown). There was a consistent and significant correlation however, between ECV and multiple parameters of LV function (LVEF, LVESVI, global longitudinal strain (GLS) and E/eʹ), as well as NTproBNP. The amount of LGE in the cohort was small and there was no significant difference in CMR measured LVEF, LVESVI or GLS, E/eʹ or NTproBNP between patients with or without LGE.

Four patients undergoing surgery were unable to complete cardiorespiratory symptom-limited CPET due to non-cardiorespiratory causes (severe osteoarthritis and anxiety). Mean peak oxygen consumption (VO2) was 23.2 ± 7.4 ml/kg/min, giving a %PredVO2max of 92.9 ± 20.5%, at an age-predicted heart rate of 99.0 ± 14.8%. On linear regression, formally tested exercise capacity quantified as %PredVO2 max was significantly associated with ECV, markers of biventricular systolic function, E/eʹ, the presence of atrial fibrillation, and pulmonary artery systolic pressure, but not with CVFmean (Table 3).

Impact of MR subtype

Sub-group analysis of patients with BD demonstrated higher CVFmax compared to FED patients (median 28.0% [IQR 16.7–42.8] vs. 20.2% [7.5–29.4], P = 0.009), but not CVFmean (15.4% [12.1–25.3] vs. 14.0% [5.5–19.1], P = 0.071). There were no significant differences in biventricular volumes, LVEF, LVMI or MR severity; ECV and LGE prevalence were also similar (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Discussion

This is the most comprehensive study to characterise myocardial changes in patients with chronic primary severe MR, combining CMR based assessment of structural changes with detailed invasive histological profiling, and the identification of functional correlates.

Our work provides definitive histological evidence for the presence of myocardial fibrosis, even in asymptomatic MR patients with normal range CMR volumetric parameters and good exercise capacity. We noted complex morphology and topography of fibrosis with three main patterns: thickened endocardium with increased fibrosis in biopsies containing sub endocardium; cellular hypertrophy and increased fibrosis compared to controls; and a variable degree of fat infiltration. Despite the increase in fibrosis compared to control subjects without MR, both in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients, the extent of fibrosis on myocardial biopsy at the time of surgery was not related to LVEF, GLS, diastolic function (E/e′; left atrial volume) or MR severity. Biopsy and CMR offered complementary information however, because patterns of fibrosis proved variable, and CMR-derived ECV and LGE were not able to capture the subendocardial changes highlighted on histology. Hence, while the extent of fibrosis on myocardial biopsy was related to symptoms but was not related to LV function, non-invasive tissue characterisation with ECV was associated with changes in both systolic and diastolic function, and measured exercise capacity.

The new finding of significant myocardial fibrosis in asymptomatic patients contrasts with early autopsy data, which found a significant increase in the size of the interstitial space only in those patients with severe MR (NYHA Class III–IV) who died early after mitral valve replacement from cardiac failure with low cardiac output syndrome [4]. Although the study did document an increase in size of the interstitial space in less symptomatic patients with severe MR (NYHA Class II–III) but who died early after mitral valve replacement from causes other than cardiac failure, this was not significant compared to autopsy controls. We believe there are technical issues and issues of sensitivity that explain these differences. Firstly, the retrospective study by Fuster et al. used hearts collected in 10% formalin over a 10-year period 1962–1972 and quantified the interstitial space using photographs on which the interstitial space was highlighted in white pen, without histological characterisation. In contrast, samples in our study were stained for fibrosis that was then quantified directly, as was the degree of fatty infiltration. Secondly, we suspect that ECV may be a more sensitive 3D measure of the interstitial space, while acknowledging that the range of ECV observed within our surgical cohort (27.3 ± 3.2%) was only mildly raised compared to the mean ECV of 25.9% (95% CI 25.5–26.3%) within a recent pooled analysis of 3872 participants [20]. This low-grade ECV expansion observed within our study may be related to disease duration, which is difficult to quantify, but most of our patients were under follow-up in valve clinic and were referred for early surgery, while LV size, function and mass were normal, and with unrestricted exercise capacity on formal testing. This latter pooled analysis also highlights the large confidence intervals and significant overlap in T1 and ECV values between health and disease [20], which reflects the recognised limitations of ECV and T1 analyses.

Despite evidence that high native T1, elevated ECV, and LGE measure diffuse interstitial and replacement fibrosis in other diseases [21,22,23,24], we found no correlation between overall CVFmean and CMR measures of fibrosis. There are a number of potential reasons for this. Similar to previous reports [7], we noted the incidence of LGE to be 34% in our MR cohort, but the most common location was in the basal inferolateral LV wall and associated papillary muscles. Although the inferolateral wall was one of the three pre-specified targets to be biopsied, the focal nature of the fibrosis means this could have been missed. This situation is best exemplified by the low sensitivity of myocardial biopsy in the diagnoses of cardiac sarcoidosis [25], and mirrors the data for aortic valve diseases where some groups have been able to demonstrate a significant correlation between histological and CMR quantified fibrosis [24], whilst others have not [26]. We report a low ICC for CVF from multiple biopsy sites within the same heart; this finding is reminiscent of the large (43%) coefficient of variation reported for interstitial fibrosis (but only 3% for cardiomyocyte CSA) in dilated cardiomyopathy [27]. This may also help to explain why ECV—a measure of global myocardial status, correlated with CMR measures of biventricular systolic function and echo derived E/e, highlighting the potential value of ECV as a marker of LV remodelling in MR. Finally, avoidance of the endocardium during quantification of ECV to prevent blood pool contamination may also contribute to the discordant results with histology, a hypothesis which is supported by our sub-analyses on myocardium-only derived CVF. However, ECV in itself has limitations, including cross over of ranges between health and disease, practical limitations of movement with respiration, and further research is needed on whether ECV offers incremental prognostic value over traditional cardiac biomarkers such as NTproBNP.

Limitations

This study was observational in nature and therefore no causation can be inferred. Although pre-specified, invasive myocardial biopsy was not performed in all patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic MR who went forward to surgery due to technical difficulties. Despite this, we provide the largest histologic characterisation of patients with severe primary MR. We were unable to anatomically match the location of the autopsy sections with the location of our histological biopsies. However, there is no evidence for significant regional variations in CVF quantity in the healthy heart and therefore this limitation should not detract from the significant difference in CVF observed between MR patients and controls. Similarly, anatomical matching of the location of biopsy collection with the commonly observed location LGE in MR is difficult, and is likely to contribute towards the lack of association between CVF and LGE quantification. Invasive measurement of pulmonary artery pressures was performed at the clinician’s discretion and was not a requirement of this study. Although assessment by echocardiography was performed, there were cases inevitably without enough tricuspid regurgitation for pulmonary artery systolic pressure to be measured. Finally, the narrower range of global fibrosis quantified by ECV may have weakened our ability to detect correlations, where a broader range always favours the likelihood of obtaining significant results. However, studying a group of severe MR patients early in their disease process increases the clinical relevance of our findings given the trend for earlier surgical assessment of asymptomatic patients.

Conclusions

Histological evidence of diffuse interstitial and replacement myocardial fibrosis, along with concomitant cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is present in asymptomatic MR, in the presence of normal range LV volume and LVEF. Fibrosis on biopsy is patchy and highly variable within the heart, which may contribute to the lack of correlation with T1 mapping, ECV and LGE. ECV, as a marker of global myocardial status, correlated well with multiple measures of ventricular function in MR. Further studies are warranted to investigate whether latent fibrosis detected using T1, ECV or LGE offer incremental value in predicting post-operative outcome in asymptomatic patients with severe primary MR.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed supporting the conclusions of the article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- CMR:

-

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance

- CPET:

-

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing

- CSA:

-

Cross sectional area

- CVFmean :

-

Mean collagen volume fraction

- CVFmax :

-

Maximum collagen volume fraction

- DIF:

-

Diffuse interstitial fibrosis

- ECV:

-

Extracellular volume fraction

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- FED:

-

Fibroelastic deficiency

- GCS:

-

Global circumferential strain

- GLS:

-

Global longitudinal strain

- LAVI:

-

Left atrial volume index

- LGE:

-

Late gadolinium enhancement

- LV:

-

Left ventricle/left ventricular

- LVEDVI:

-

Left ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed to body surface area

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- LVESD:

-

Left ventricular end-systolic diameter

- LVESVI:

-

Left ventricular end-systolic volume indexed to body surface area

- LVMI:

-

Left ventricular mass indexed to body surface area

- MOLLI:

-

Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery

- MR:

-

Mitral regurgitation

- NTproBNP:

-

N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- PASP:

-

Pulmonary artery systolic pressure

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- RV:

-

Right ventricle/right ventricular

- RVEF:

-

Right ventricular ejection fractino

- VO2 :

-

Oxygen consumption

References

Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Fleisher LA, Jneid H, Mack MJ, McLeod CJ, O’Gara PT, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252–89.

Enriquez-Sarano M, Suri RM, Clavel MA, Mantovani F, Michelena HI, Pislaru S, Mahoney DW, Schaff HV. Is there an outcome penalty linked to guideline-based indications for valvular surgery? Early and long-term analysis of patients with organic mitral regurgitation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150(1):50–8.

Liu B, Edwards NC, Pennell D, Steeds RP. The evolving role of cardiac magnetic resonance in primary mitral regurgitation: ready for prime time? Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20(2):123–30.

Fuster V, Danielson MA, Robb RA, Broadbent JC, Brown AL, Elveback LR. Quantitation of left-ventricular myocardial fiber hypertrophy and interstitial-tissue in human hearts with chronically increased volume and pressure overload. Circulation. 1977;55(3):504–8.

Brower GL, Janicki JS. Contribution of ventricular remodeling to pathogenesis of heart failure in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280(2):H674–83.

Han Y, Peters DC, Salton CJ, Bzymek D, Nezafat R, Goddu B, Kissinger KV, Zimetbaum PJ, Manning WJ, Yeon SB. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance characterization of mitral valve prolapse. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(3):294–303.

Kitkungvan D, Nabi F, Kim RJ, Bonow RO, Khan MA, Xu JQ, Little SH, Quinones MA, Lawrie GM, Zoghbi WA, et al. Myocardial fibrosis in patients with primary mitral regurgitation with and without prolapse. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(8):823–34.

Edwards NC, Moody WE, Yuan MS, Weale P, Neal D, Townend JN, Steeds RP. Quantification of left ventricular interstitial fibrosis in asymptomatic chronic primary degenerative mitral regurgitation. Circ-Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(6):946–53.

Liu B, Edwards NC, Neal DAH, Weston C, Nash G, Nikolaidis N, Barker T, Patel R, Bhabra M, Steeds RP. A prospective study examining the role of myocardial Fibrosis in outcome following mitral valve repair IN DEgenerative mitral Regurgitation: rationale and design of the mitral FINDER study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17(1):282.

Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Munoz DR, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease The task force for the management of valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2017;38(36):2739.

Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Andreotti F, Antunes MJ, Baron-Esquivias G, Baumgartner H, Borger MA, Carrel TP, De Bonis M, Evangelista A, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33(19):2451–96.

Sommer C, Straehle C, Kothe U, Hamprecht FA. IEEE: Ilastik: interactive learning and segmentation toolkit. In: 2011 8th IEEE international symposium on biomedical imaging: from nano to macro. 2011: 230–3.

Maceira AM, Prasad SK, Khan M, Pennell DJ. Normalized left ventricular systolic and diastolic function by steady state free precession cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2006;8(3):417–26.

Maceira AM, Cosin-Sales J, Roughton M, Prasad SK, Pennell DJ. Reference left atrial dimensions and volumes by steady state free precession cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2010;12:65.

Vijapurapu R, Hawkins F, Liu BY, Edwards N, Steeds R. A study of the different methodologies used in calculation of extra-cellular volume by CMR imaging. Heart. 2018;104:A14–5.

Liu B, Dardeer AM, Moody WE, Hayer MK, Baig S, Price AM, Leyva F, Edwards NC, Steeds RP. Reference ranges for three-dimensional feature tracking cardiac magnetic resonance: comparison with two-dimensional methodology and relevance of age and gender. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;34:761–75.

Liu B, Dardeer AM, Moody WE, Edwards NC, Hudsmith LE, Steeds RP. Normal values for myocardial deformation within the right heart measured by feature-tracking cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2017;252:220–3.

Mikami Y, Kolman L, Joncas SX, Stirrat J, Scholl D, Rajchl M, Lydell CP, Weeks SG, Howarth AG, White JA. Accuracy and reproducibility of semi-automated late gadolinium enhancement quantification techniques in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2014;16:85.

ATS/ACCP. Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(2):211–277.

Gottbrecht M, Kramer CM, Salerno M. Native T1 and extracellular volume measurements by cardiac MRI in healthy adults: a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2019;290(2):317–26.

de Ravenstein CdM, Bouzin C, Lazam S, Boulif J, Amzulescu M, Melchior J, Pasquet A, Vancraeynest D, Pouleur A-C, Vanoverschelde J-LJ, et al. Histological validation of measurement of diffuse interstitial myocardial fibrosis by myocardial extravascular volume fraction from Modified Look-Locker imaging (MOLLI) T1 mapping at 3 T. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2015;17:48.

Flett AS, Hayward MP, Ashworth MT, Hansen MS, Taylor AM, Elliott PM, McGregor C, Moon JC. Equilibrium contrast cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the measurement of diffuse myocardial fibrosis: preliminary validation in humans. Circulation. 2010;122(2):138–44.

Messroghli DR, Walters K, Plein S, Sparrow P, Friedrich MG, Ridgway JP, Sivananthan MU. Myocardial T1 mapping: application to patients with acute and chronic myocardial infarction. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(1):34–40.

Azevedo CF, Nigri M, Higuchi ML, Pomerantzeff PM, Spina GS, Sampaio RO, Tarasoutchi F, Grinberg M, Rochitte CE. Prognostic significance of myocardial fibrosis quantification by histopathology and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with severe aortic valve disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(4):278–87.

Hulten E, Aslam S, Osborne M, Abbasi S, Bittencourt MS, Blankstein R. Cardiac sarcoidosis-state of the art review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2016;6(1):50–63.

Treibel TA, Lopez B, Gonzalez A, Menacho K, Schofield RS, Ravassa S, Fontana M, White SK, DiSalvo C, Roberts N, et al. Reappraising myocardial fibrosis in severe aortic stenosis: an invasive and non-invasive study in 133 patients. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(8):699–709.

Schwarz F, Mall G, Zebe H, Blickle J, Derks H, Manthey J, Kubler W. Quantitative morphologic findings of the myocardium in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1983;51(3):501–6.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was fully funded by the British Heart Foundation (PG/14/74/31056). JM and TT are directly and indirectly supported by the University College London Hospitals (UCLH), Barts NIHR Biomedical Research Centres and the British Heart Foundation accelerator award. TT is funded with British Heart Foundation Intermediate Research Fellowship (FS/19/35/34374).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BL, DN, NE, RS were involved in the conception and design of the study. BL, DN, NE and RS were involved in data collection. BL, MB, RP, TB, NN and SB were involved in surgical biopsy collection. AG provided autopsy control samples. BL, DN, MP, NE and RS were involved in data analyses. BL and JH were responsible for statistical analyses. BL, NE and RS were responsible for drafting of manuscript. BL, TT, JM, NE and RS were responsible for critically revising the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the UK National Research Ethics Service (15/EM/0243) and conformed to the Helsinki Declaration. Subjects gave written informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest or relationship with industry.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Clinical characteristics of conservative and surgical patients. Table S2. Cardiac magnetic resonance parameters according to subtype of MR. Table S3. CVFmean values according to symptom status and biopsy type.

Additional file 2: Figure S1

. Scatter plots demonstrating the correlation between regional ECV and CVF in the A) septum (rho = − 0.05, P = 0.683), B) anterior wall (rho = − 0.02, P = 0.886) and C) posterior wall (rho = 0.22, P = 0.150) of the left ventricle.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, B., Neil, D.A.H., Premchand, M. et al. Myocardial fibrosis in asymptomatic and symptomatic chronic severe primary mitral regurgitation and relationship to tissue characterisation and left ventricular function on cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 22, 86 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00674-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00674-4