Abstract

Background

Physical independence is crucial for overall health in the elderly individuals. The life expectancy of women has been shown to be higher than that of men, which is also known as the “male–female health-survival paradox”. Sex hormones may be one of the explanations. However, the relationships between sex hormones and physical function remain unclear in the elderly females. This study was designed to explore these relationships among the Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women.

Methods

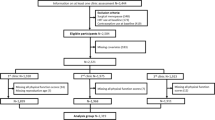

Data from 1226 women were obtained from the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study. Home interviews, physical examinations and blood analyses were conducted using standardized procedures. Variables including age, Han ethnicity, illiteracy, smoker, drinker, estradiol (E2), testosterone (T), follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone were used in the multivariate logistic and linear regression analyses.

Results

In all the participants, age [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.84 (− 0.98, − 0.71)] and E2 levels [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.22 (− 0.28, − 0.17)] were negatively associated with activities of daily living (ADLs) in the multivariate linear regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all). We also observed significantly negative associations of age [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.90 (0.88, 0.91)] and E2 levels [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.98 (0.98, 0.99)] with physical normality in the multivariate logistic regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all). Age and E2 levels gradually decreased with increases in the ADL quartiles across all the participants (P < 0.05 for all).

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that E2 levels were negatively associated with physical function among the Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Aging is characterized by the decline in the physiological regulatory functions with adverse effects on physical health and functional autonomy [1]. Decreased physical function, including musculoskeletal, neurological, circulatory, cognitive, and mental function, can lead to a fragile physical state, triggering functional dependence in the elderly individuals. Elderly individuals are more susceptible to the decline in the activities of daily living (ADLs), such as eating, self-care, and movement [2]. As the pace of global aging accelerates, achieving healthy aging has become a primary issue. Epidemiological data have shown that the life expectancy of women are higher than those of men, which is also known as the “male–female health-survival paradox” [3, 4]. Sex hormones may be one of the explanations. Both estradiol (E2) and testosterone (T) production are controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary–gonadal axis, which stimulates sex steroid production by increasing the secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete gonadotropins, including luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Loss of negative feedback by E2 and T on gonadotropin production after menopause results in an increase in the serum LH and FSH concentrations [5]. It is has been suggested that E2 may be associated with inflammatory processes, oxidative stress and lipid metabolism and beneficial to the cardiovascular system, physical function and healthy aging [6]. With the loss of E2, postmenopausal women undergo a number of processes in which risk factors for cardiovascular disease rapidly rise. However, age-related changes in the E2 and T levels in the older adults, especially older women, have not been fully explored. A previous analysis of women aged 18–75 years showed a steep decline in the T levels over early reproductive ages, flattened out in the midlife, and increased slightly in the later years [7]. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging reported that T declined with age before menopause and increased slightly afterward [8]. Given all of this information, little is known about the relationships between sex hormones and ADLs in the elderly females. Based on data from 1226 women over 80 years of age from the China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study (CHCCS), we described age-related trajectories of sex hormones among the oldest-old and centenarian women, with a particular focus on their relationships with physical function.

Methods

Study population

The entire study sample was obtained from the CHCCS, which was conducted from June 2014 to December 2016. Based on a list of oldest-old and centenarian adults provided by the Department of Civil Affairs of Hainan Province, China, this cross-sectional study conducted a household survey with all the oldest-old and centenarian adults residing in the 16 cities and counties in the Hainan Province. In brief, a total of 1308 women (486 aged 80–99 years and 822 aged 100 years and over) were interviewed, with basic information and blood analyses available for 1226 participants. Home interviews, physical examinations and blood analyses were conducted using standardized procedures [9]. No participant was receiving sex hormone drugs or postmenopausal sex hormone replacement treatment.

Functional performance

We used the Barthel index to evaluate ADLs in the elderly individuals. The Barthel index consists of ten items measuring a person’s daily activities: grooming, feeding, dressing, bathing, toilet use, transferring from bed to chair, walking, stair climbing, bowel continence, and urinary continence. Each item of ADLs is rated on a scale with a given number of points assigned to each level of activity, and the total scores range from 0 to 100 points with 5-point increments. The surveyors, who were strictly trained before the investigation, evaluated the Barthel index by observing the completion of each action. Higher Barthel index indicated better ADLs. Physical normality was defined by a total score ≥ 95 points, and physical decline was defined by a total score < 95 points [10].

Hormone assays

A disposable vacuum negative pressure blood sampler was used by experienced nurses to collect blood samples from the elbow vein of the participants in a sitting position. Blood samples were stored at 4 °C and transported to our Central Laboratory within the 4 h. Serum E2 (pmol/L), T (nmol/L), FSH (mIU/mL) and LH (mIU/mL) levels were measured by electrochemiluminescence (Cobas E602) using the Elecsys Estradiol III Kit, Elecsys Testosterone II Kit, Elecsys FSH Kit, and Elecsys LH Kit (Roche, Germany). The lower detection thresholds were 18.4 pmol/L, 0.087 nmol/L, 0.100 mIU/mL, and 0.100 mIU/mL, respectively.

Concomitant variables

Home interviews were conducted by native doctors and nurses who were trained to interview and could speak the local dialect to collect demographic details (age, ethnicity, and education) and lifestyle factors (smoker or nonsmoker and drinker or nondrinker) of the participants as concomitant variables. Ethnicity was divided into “Han ethnicity” and “non-Han ethnicity”. Education was classified as “illiteracy” and “literacy”.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences Version 17 (Chicago, IL, USA). Numbers and percentages are presented for categorical variables, and medians and interquartile ranges are presented for continuous variables with skewed distributions. Categorical variables were compared with Chi-square tests, and continuous variables with skewed distributions were compared with Mann–Whitney U tests. Multivariate linear regression analyses were used to explore independent factors associated with age and ADLs. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine independent associations with centenarian women/oldest-old women and physical normality/decline. Variables including age, Han ethnicity, illiteracy, smoker, drinker, and E2, T, E2/T, FSH, and LH levels were used in the multivariate logistic and linear regression analyses. A P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

A comparison of characteristics between oldest-old women and centenarian women is shown in the Table 1. Centenarian women accounted for 61.8% of the sample (758 participants). Centenarian women had significantly higher age, higher levels of E2, and lower levels of ADLs than oldest-old women (P < 0.05 for all). As shown in the Table 2, we observed that E2 levels [beta (95% confidence interval): 0.05 (0.03, 0.07)] were positively associated with age, whereas ADLs [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.13 (− 0.15, − 0.11)] were negatively associated with age in the multivariate linear regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all). We then tested our results in the multivariate logistic regression analysis: a positive association between E2 levels [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 1.04 (1.02, 1.05)] and centenarians and a negative association between ADLs [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.94 (0.93, 0.95)] and centenarians remained significant in all the participants (P < 0.05 for all; Table 2). E2 levels gradually increased and ADLs gradually decreased with increases in the age quartiles (P < 0.05 for all; Table 3).

Table 4 summarizes the characteristics by functional performance in all the participants. The proportion of physical normality was 44.8% (549 participants). The participants with physical normality had significantly lower age, lower levels of E2 and LH, and higher levels of ADLs than those with physical decline (P < 0.05 for all). As shown in the Table 5, age [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.84 (− 0.98, − 0.71)] and E2 levels [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.22 (− 0.28, − 0.17)] were negatively associated with ADLs in the multivariate linear regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all). We also observed significantly negative associations of age [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.90 (0.88, 0.91)], E2 levels [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.98 (0.98, 0.99)], and LH levels [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.99 (0.97, 1.00)] with physical normality in the multivariate logistic regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all; Table 6). Age and E2 levels gradually decreased with increases in the ADL quartiles across all the participants (P < 0.05 for all; Table 3).

When dividing all the participants into oldest-old women and centenarian women, we compared the characteristics between those with physical normality or decline in the Table 4. Among the oldest-old women, age and LH levels were significantly lower in the participants with physical normality than in those with physical decline (P < 0.05 for all). Among the centenarian women, E2, T and LH levels were significantly lower in the participants with physical normality than in those with physical decline (P < 0.05 for all). As shown in the Table 5, age [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.51 (− 0.79, − 0.23)] was negatively associated with ADLs among the oldest-old women, and E2 [beta (95% confidence interval): − 0.23 (− 0.30, − 0.17)] and T [beta (95% confidence interval): − 1.83 (− 3.15, − 0.51)] levels were negatively associated with ADLs among the centenarian women in the multivariate linear regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all). In addition, the negative association between age [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.91 (0.87, 0.96)] and physical normality remained robust among the oldest-old women but not among the centenarian women, and the negative association between E2 levels [odds ratio (95% confidence interval): 0.98 (0.97, 0.99)] and physical normality remained robust among the centenarian women but not among the oldest-old women in the multivariate logistic regression analyses (P < 0.05 for all; Table 6).

Discussion

Physical independence is an important aspect of aging and a key factor affecting quality of life in the elderly population. Limited data exist on the relationships between sex hormones and physical function among the oldest-old and centenarian women in developing countries. Previous studies in China found a greater decline in physical function in the oldest-old group (≥ 80 years) than in the other two age groups (60–69 and 70–79 years) [11]. Studies in Spain showed that physical decline was independently associated with being a woman, lower educational status, and age over 85 years [12,13,14,15]. Studies in United States and Sweden showed that physical function remained steady over time, with a gradual tendency for performance to decline [16, 17]. A study conducted in Denmark suggested that the basis for improved physical function is superior living conditions and cognitive function in the older adults, as well as better aids in supporting mobility and independence [16]. Additionally, lifestyle, exercise, diet, and personality are also contributors that affect physical function [18, 19]. Our results showed a proportion of physical normality of approximately 44.8% and provide novel insight into this significant field of study, with large sample analyses of Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women. In this study, centenarian women were reported to have poor physical function than oldest-old women, and E2 levels were negatively associated with physical function among the Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women.

This finding may highlight the role of E2 in age-related loss of muscle mass and strength and provide the basis for E2-based interventions to prevent physical decline among those living past the age of one hundred. It is well known that skeletal muscle weakness is an adverse consequence of aging. Sarcopenia, an age-related loss of muscle mass and strength, is considered to be a precursor of frailty and can cause elderly individuals to lose physical independence [20]. The size and strength of women's skeletal muscle are affected by both age and ovarian hormones [21]. A meta-analysis of nearly 10,000 postmenopausal women showed that women who received sex hormone treatment had slightly stronger muscle strength than those not on sex hormone treatment [22]. It has been reported that E2 can not only affect muscle protein conversion and the ubiquitin–proteasome system but also protect skeletal muscle from apoptosis by acting on heat shock proteins and mitochondria [23,24,25,26]. Meanwhile, E2 is also produced in various brain regions [27]. E2 levels in the hippocampus are affected by E2 circulation. These results suggest that postmenopausal women may not be able to produce significant levels of E2 in both the reproductive tract and hippocampus [28]. Combined with the evidence that E2 levels in the hippocampus may have neuroprotective effects, decreased E2 levels in the postmenopausal women may make the hippocampus more vulnerable to degeneration [29]. Large randomized clinical trials have shown that sex hormone treatment did not improve cognitive function in the older postmenopausal women and may even have an adverse effect on cognitive function [30,31,32,33]. Brinton proposed a healthy cell bias of E2 action, suggesting that E2 could be beneficial to healthy cells but detrimental to degraded or already damaged cells [34]. This is because high doses of E2 increase intracellular Ca2+, which could exacerbate the development of neurodegeneration due to Ca2+ dysregulation [35]. A previous study identified a negative effect of E2 treatment on cognitive function, indicating a faster progression of Alzheimer's disease in the elderly individuals with E2 supplementation [36].

The physiological implications of changed sex hormones are still being clarified within the different age groups and with the different physical conditions. E2 treatment did not seem to have health benefits for elderly individuals with intact ovaries; elderly individuals who had their ovaries removed may experience harmful effects from E2 treatment [37]. Moreover, the effects of E2 in the brain regions involved in the response to stress and emotion may be associated with increased negative mood and depressive symptoms in the perimenopausal and postmenopausal women [38,39,40]. Studies have reported that E2 administration in the postmenopausal women without a history of mood disorders was associated with an increased negative mood response to a psychosocial stressor [41, 42]. This suggested a shift from beneficial effects of E2 in the premenopausal women to negative effects in the postmenopausal women without depression vulnerability. In other words, E2 has multidimensional effects on the body, cognition and emotion of postmenopausal women, which are different from those of premenopausal women. Our data showed that a significant association between E2 levels and physical normality remained in the centenarian women but not in the oldest-old women, prompting us to further explore these issues from multiple perspectives to elucidate the effects of E2 in women in different advanced age ranges. In our study, centenarian women had significantly higher levels of E2 and lower levels of ADLs than oldest-old women, providing E2 with the opportunity to influence physical function, whereas due to lower levels of E2 and higher levels of ADLs in the oldest-old women, E2 had no significant chance to affect physical function. It is possible that the different E2 levels and physical conditions within the different age groups resulted in the existence of a negative association in the centenarian women and not oldest-old women. A nationwide survey provided evidence that the prevalence of physical decline among Chinese older adults declined from 1997 to 2006, consistent with the Shanghai study from 1998 to 2008 [11, 43]. This may be because the fact that the new medical insurance policy implemented since 2000 may help older residents improve medical services, which to some extent explained that the oldest-old adults gained more benefits due to their age advantages at that time. On the other hand, this is relevant given that the improved living standard may help older residents improve their overall health status and physical function.

Our team reported that E2 levels of centenarian women were higher than those of oldest-old women. There are wide variations in the levels of sex hormones in women throughout the lifespan. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging reported progressive decreases in the E2 and T levels in the premenopausal women and increases at older ages [8]. Endogenous E2 and T were related to changed endothelial function in the postmenopausal women [44]. A 12-year follow-up study of postmenopausal women showed that abnormal E2 and T levels were associated with an increased risk for adverse events [45]. Meanwhile, LH and FSH are controlled by complex feedback loops in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. In the absence of changed feedback from sex hormones after menopause, increased LH levels are related to cognitive deficit and Alzheimer’s disease in the elderly individuals [46, 47]. Increased LH levels in patients with Alzheimer’s disease could exacerbate pathological cognitive decline [48,49,50,51]. This is because LH modulates amyloid-β protein precursor processing [52]. Elevated LH levels are correlated with increased plasma Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 levels [50]. Studies in patients without Alzheimer’s disease have shown that increased FSH levels improve cognitive function [53, 54]. In a study of 649 women over 70 years old without cognitive decline, it was found that higher FSH levels were associated with improved cognitive function [46, 55]. In our results, T, LH and FSH levels had no statistically significant associations with physical function among Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women.

This study has some potential limitations. First, we conducted a cross-sectional survey. Therefore, a corresponding cohort study with follow-up data should be conducted to strengthen the evidence. Second, the findings were based on self-reported information, and there may be subjectivity derived from this approach in this study.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that E2 levels were negatively associated with physical function among the Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women, suggesting that the roles of E2 should be more comprehensively studied in future basic and clinical studies.

Availability of data and materials

In an attempt to preserve the privacy of individuals, clinical data will not be shared; the data can be available from authors upon request.

Abbreviations

- ADL:

-

Activity of daily living

- CHCCS:

-

China Hainan Centenarian Cohort Study

- E2:

-

Estradiol

- FSH:

-

Follicle-stimulating hormone

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- T:

-

Testosterone

References

Singh PP, Demmitt BA, Nath RD, Brunet A. The genetics of aging: a vertebrate perspective. Cell. 2019;177:200–20.

Ostchega Y, Harris TB, Hirsch R, Parsons VL, Kington R. The prevalence of functional limitations and disability in older persons in the US: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey III. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1132–5.

Perls T, Kunkel L, Puca A. The genetics of aging. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2002;12:362–9.

Gordon EH, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. The male-female health-survival paradox in hospitalised older adults. Maturitas. 2018;107:13–8.

Chakravarti S, Collins WP, Forecast JD, Newton JR, Oram DH, Studd JW. Hormonal profiles after the menopause. BMJ. 1976;2:784–7.

Masood DN, Roach EC, Beauregard KG, Khalil RA. Impact of sex hormone metabolism on the vascular effects of menopausal hormone therapy in cardiovascular disease. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11:693–714.

Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3847–53.

Fabbri E, An Y, Gonzalez-Freire M, Zoli M, Maggio M, Studenski SA, et al. Bioavailable testosterone linearly declines over a wide age spectrum in men and women from the baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71:1202–9.

Fu S, Hu J, Chen X, Li B, Shun H, Deng J, et al. Mutant single nucleotide polymorphism rs189037 in ataxia-telangiectasia mutated gene is significantly associated with ventricular wall thickness and human lifespan. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8: 658908.

Quinn TJ, Langhorne P, Stott DJ. Barthel index for stroke trials. Stroke. 2011;42:1146–51.

Liang Y, Song A, Du S, Guralnik JM, Qiu C. Trends in disability in activities of daily living among Chinese older adults, 1997–2006: the China health and nutrition survey. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;70:739–45.

Arnau A, Espaulella J, Serrarols M, Canudas J, Formiga F, Ferrer M. Factores asociados al estado funcional en personas de 75 o más años de edad no dependientes. Gac Sanit. 2012;26:405–13.

Millán-Calenti JC, Tubío J, Pita-Fernández S, González-Abraldes I, Lorenzo T, Fernández-Arruty T, et al. Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;50:306–10.

Palacios-Ceña D, Jiménez-García R, Hernández-Barrera V, Alonso-Blanco C, Carrasco-Garrido P, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C. Has the prevalence of disability increased over the past decade (2000–2007) in elderly people? A Spanish population-based survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:136–42.

Carmona-Torres JM, Rodríguez-Borrego MA, Laredo-Aguilera JA, López-Soto PJ, Santacruz-Salas E, Cobo-Cuenca AI. Disability for basic and instrumental activities of daily living in older individuals. PLoS ONE. 2019;14: e0220157.

Christensen K, Thinggaard M, Oksuzyan A, Steenstrup T, Andersen-Ranberg K, Jeune B, et al. Physical and cognitive functioning of people older than 90 years: a comparison of two Danish cohorts born 10 years apart. Lancet. 2013;382:1507–13.

Angleman SB, Santoni G, Von Strauss E, Fratiglioni L. Temporal trends of functional dependence and survival among older adults from 1991 to 2010 in Sweden: toward a healthier aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;70:746–52.

Vermeulen J, Neyens JCL, van Rossum E, Spreeuwenberg MD, de Witte LP. Predicting ADL disability in community-dwelling elderly people using physical frailty indicators: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:33.

Zhang J, Zhao A, Wu W, Ren Z, Yang C, Wang P, et al. Beneficial effect of dietary diversity on the risk of disability in activities of daily living in adults: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients. 2020;12:3263.

Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley JE, Newman AB, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:249–56.

Collins BC, Laakkonen EK, Lowe DA. Aging of the musculoskeletal system: how the loss of estrogen impacts muscle strength. Bone. 2019;123:137–44.

Zhang YJ, Fu SH, Wang JX, Zhao X, Yao Y, Li XY. Value of appendicular skeletal muscle mass to total body fat ratio in predicting obesity in elderly people: a 2.2-year longitudinal study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:143.

Hansen M. Female hormones: do they influence muscle and tendon protein metabolism? Proc Nutr Soc. 2017;77:32–41.

Dieli-Conwright CM, Spektor TM, Rice JC, Sattler FR, Schroeder ET. Influence of hormone replacement therapy on eccentric exercise induced myogenic gene expression in postmenopausal women. J Appl Physiol. 2009;107:1381–8.

Boland R, Vasconsuelo A, Milanesi L, Ronda A, Deboland A. 17β-estradiol signaling in skeletal muscle cells and its relationship to apoptosis. Steroids. 2008;73:859–63.

La Colla A, Vasconsuelo A, Boland R. Estradiol exerts antiapoptotic effects in skeletal myoblasts via mitochondrial PTP and MnSOD. J Endocrinol. 2012;216:331–41.

Russell JK, Jones CK, Newhouse PA. The role of estrogen in brain and cognitive aging. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16:649–65.

Herrera AY, Mather M. Actions and interactions of estradiol and glucocorticoids in cognition and the brain: implications for aging women. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:36–52.

Barker JM, Galea LAM. Sex and regional differences in estradiol content in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala and hippocampus of adult male and female rats. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2009;164:77–84.

Espeland MA, Rapp SR, Shumaker SA, Brunner R, Manson JE, Sherwin BB, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and global cognitive function in postmenopausal women: women’s health initiative memory study. JAMA. 2004;291:2959–68.

Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Shumaker SA, Henderson VW, Brunner RL, Manson JE, et al. Effect of estrogen plus progestin on global cognitive function in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2003;289:2663–72.

Resnick SM, Maki PM, Rapp SR, Espeland MA, Brunner R, Coker LH, et al. Effects of combination estrogen plus progestin hormone treatment on cognition and affect. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1802–10.

Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 2003;289:2651–62.

Brinton RD. Investigative models for determining hormone therapy-induced outcomes in brain: evidence in support of a healthy cell bias of estrogen action. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1052:57–74.

Chen S, Nilsen J, Brinton RD. Dose and temporal pattern of estrogen exposure determines neuroprotective outcome in hippocampal neurons: therapeutic implications. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5303–13.

Mulnard RA, Cotman CW, Kawas C, van Dyck CH, Sano M, Doody R, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy for treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2000;283:1007–15.

Manson JE, Aragaki AK, Bassuk SS, Chlebowski RT, Anderson GL, Rossouw JE, et al. Menopausal estrogen-alone therapy and health outcomes in women with and without bilateral oophorectomy. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:406–14.

Cover KK, Maeng LY, Lebrón-Milad K, Milad MR. Mechanisms of estradiol in fear circuitry: implications for sex differences in psychopathology. Transl Psychiatry. 2014;4: e422.

García-García I, Kube J, Gaebler M, Horstmann A, Villringer A, Neumann J. Neural processing of negative emotional stimuli and the influence of age, sex and task-related characteristics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;68:773–93.

Gordon JL, Rubinow DR, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Leserman J, Girdler SS. Estradiol variability, stressful life events, and the emergence of depressive symptomatology during the menopausal transition. Menopause. 2016;23:257–66.

Newhouse PA, Dumas J, Hancur-Bucci C, Naylor M, Sites CK, Benkelfat C, et al. Estrogen administration negatively alters mood following monoaminergic depletion and psychosocial stress in postmenopausal women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;33:1514–27.

Albert K, Ledet T, Taylor W, Newhouse P. Estradiol administration differentially affects the response to experimental psychosocial stress in post-menopausal women with or without a history of major depression. J Affect Disord. 2020;261:204–10.

Feng Q, Zhen Z, Gu D, Wu B, Duncan PW, Purser JL. Trends in ADL and IADL disability in community-dwelling older adults in Shanghai, China, 1998–2008. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2013;68(3):476–85.

Montalcini T, Gorgone G, Gazzaruso C, Sesti G, Perticone F, Pujia A. Endogenous testosterone and endothelial function in postmenopausal women. Coron Artery Dis. 2007;18:9–13.

Fu S, Yao Y, Lv F, Zhang F, Zhao Y, Luan F. Relationships of sex hormone levels with activity of daily living in Chinese female centenarians. J Nutr Health Aging. 2019;23:753–7.

Rodrigues MA, Verdile G, Foster JK, Hogervorst E, Joesbury K, Dhaliwal S, et al. Gonadotropins and cognition in older women. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;13:267–74.

Bowen RL, Smith MA, Harris PLR, Kubat Z, Martins RN, Castellani RJ, et al. Elevated luteinizing hormone expression colocalizes with neurons vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:514–8.

Bowen RL, Isley JP, Atkinson RL. An association of elevated serum gonadotropin concentrations and Alzheimer disease? J Neuroendocrinol. 2001;12:351–4.

Verdile G, Yeap BB, Clarnette RM, Dhaliwal S, Burkhardt MS, Chubb SAP, et al. Luteinizing hormone levels are positively correlated with plasma amyloid-β protein levels in elderly men. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008;14:201–8.

Verdile G, Laws SM, Henley D, Ames D, Bush AI, Ellis KA, et al. Associations between gonadotropins, testosterone and β amyloid in men at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;19:69–75.

Verdile G, Asih PR, Barron AM, Wahjoepramono EJ, Ittner LM, Martins RN. The impact of luteinizing hormone and testosterone on beta amyloid (Aβ) accumulation: animal and human clinical studies. Horm Behav. 2015;76:81–90.

Bowen RL, Verdile G, Liu T, Parlow AF, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. Luteinizing hormone, a reproductive regulator that modulates the processing of amyloid-β precursor protein and amyloid-β deposition. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20539–45.

Gordon HW, Corbin ED, Lee PA. Changes in specialized cognitive function following changes in hormone levels. Cortex. 1986;22:399–415.

Gordon HW, Lee PA. A relationship between gonadotropins and visuospatial function. Neuropsychologia. 1986;24:563–76.

Roth M, Tym E, Mountjoy CQ, Huppert FA, Hendrie H, Verma S, et al. CAMDEX: a standardised instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly with special reference to the early detection of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;149:698–709.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all those who participated in this study for their continued cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81900357, 81941021, 81903392, 81901252, 82001476, 81802804, and 81801251), the Military Medical Science and Technology Youth Incubation Program (20QNPY110 and 19QNP060), the Excellent Youth Incubation Program of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (2020-YQPY-007), the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (821QN389, 821MS112, and 818QN322), the Military Medicine Youth Program of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (QNF19069 and QNF19068), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC2000400), the National S&T Resource Sharing Service Platform Project of China (YCZYPT[2018]07), the Specific Research Fund of The Innovation Platform for Academicians of Hainan Province (YSPTZX202216), the Hainan Major Scientific and Technological Cooperation Project (2016KJHZ0039), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation funded project (2019M650359, 2020M682816, and 2021T140298), the Medical Big Data R&D Project of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (MBD2018030), the National Geriatric Disease Clinical Medicine Research Center Project (NCRCG-PLAGH-2017-014), the Central Health Care Scientific Research Project (W2017BJ12), the Hainan Medical and Health Research Project (16A200057), the Sanya Medical and Health Science and Technology Innovation Project (2016YW21, 2017YW22, 2018YW11, and 2018YW16), and the Clinical Scientific Research Supporting Fund of Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital (2017FC-CXYY-3009). The sponsors had no role in the design, conduct, interpretation, review, approval or control of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QZ, PP, PZ, CN, YZ, YY, XL, and SF contributed to the study design, conducted the data collection and analyses, and drafted the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hainan Hospital of Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital (Sanya, Hainan; Number: 301hn11201601). All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study and for their data to be used.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, Q., Ping, P., Zhang, P. et al. Sex hormones and physical function among the Chinese oldest-old and centenarian women. J Transl Med 20, 340 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03539-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03539-9